Abstract

Background

Monocytes play an important role in the fetal and neonatal inflammatory response syndrome. They are also the precursors of alveolar macrophages, microglial and Kupffer cells. Monocytes have pro-inflammatory (PI) and anti-inflammatory (AI) functions. Interleukin (IL)-10 is a potent AI cytokine released by monocytes.

Objective

We determined the effects of endogenous and exogenous IL-10 versus equimolar levels of dexamethasone (DEX) on PI and AI cytokine release, as well as transcription factor DNA-binding activity, in endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS)-stimulated monocytes of the newborn.

Methods

Monocytes were isolated into culture media from cord blood. ELISAs, electrophoretic mobility shift assays and Western blots were employed.

Results

LPS-stimulated monocyte release of PI cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1β and IL-8, over 18 h was significantly augmented by addition of an IL-10 monoclonal antibody. Exogenous IL-10 at 10−8M inhibited PI cytokine release by 89–97%, while DEX at an equimolar level had no effect. DNA-binding activities of the PI transcription factors nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1), and the AI transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) were induced over 18 h. DEX at 10−8M had no effect on any transcription factor DNA binding, but exogenous IL-10 at 10−8M produced a 60% inhibition of AP-1 DNA binding and enhanced phosphorylation of nuclear STAT3 for 18 h.

Conclusion

At therapeutic levels of DEX, monocyte release of PI cytokine was insensitive to DEX in comparison to IL-10. IL-10 or its mechanism of action could lead to new therapy for inflammatory disorders in the perinatal period.

Key Words: Monocyte, Interleukin-10, Dexamethasone, Cytokines, Transcription factors

Introduction

Control of inflammation plays an important role in serious perinatal disorders such as the fetal inflammatory response syndrome, preterm delivery, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and white matter injury [1, 2]. The innate inflammatory response is generally characterized by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) followed by monocyte recruitment, as exemplified by sequential examination of airway fluid in newborns developing BPD [3, 4]. During this process, pro-inflammatory (PI) cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-8, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IL-1β, are released from inflammatory cells [1, 2, 5, 6]. For the PMNs of the newborn, recent work has demonstrated that exogenous IL-10, an anti-inflammatory (AI) cytokine, is equipotent to dexamethasone (DEX) on a molar basis with regard to inhibition of PI cytokine release [7]. There is now increasing interest in the monocytes [8, 9] of the newborn, which are precursors for alveolar macrophages, Kupffer cells and microglial cells [10]. Monocytes from adults, in comparison to PMNs from adults, have the ability to produce greater amounts of PI and AI cytokines, and therefore may play a pivotal role in the development and resolution of inflammation [11]. However, little is known about the control of PI and AI cytokine release from monocytes of the newborn.

Postnatal corticosteroids, such as DEX, reduce the incidence of BPD, but must be used cautiously owing to potentially serious acute and long-term side effects [12, 13]. Fortunately, therapeutic levels of DEX have been measured in the plasma of newborns treated for BPD [14, 15]. These levels can serve as a benchmark for the comparison of DEX versus other potentially useful agents, such as IL-10, in cell or molecular studies. AI cytokine therapy may have potential therapeutic uses for perinatal inflammatory conditions.

With a focus on the endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS)-stimulated monocytes of the term, healthy human newborn, our study aims were to: (1) describe the temporal and quantitative release of PI and AI cytokines; (2) assess whether endogenous IL-10 release, as a counterregulatory cytokine, has any effect on PI cytokine release; (3) compare the effect of equimolar levels of DEX versus exogenous IL-10 on PI cytokine release; (4) determine interrelated transcription factor activity [16, 17]. Under our experimental conditions, we studied the PI transcription factors nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1), as well as the AI transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Fetal inflammatory response syndrome and the neonatal inflammatory response, as well as the regulation of monocyte functions may be important to clarify for both preterm and term infants. Developmental differences were not addressed by this study.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Cord blood (approximately 60 ml) was obtained from placentas after elective, term, caesarean section deliveries. One of the investigators attended each of the deliveries to exclude deliveries associated with labor, rupture of membranes, meconium-stained fluid, clinical evidence of chorioamnionitis, maternal disorders and maternal medications. Blood was collected in heparinized preservative-free tubes for transport to the laboratory, followed by immediate cell isolation. A total of 21 cord blood samples were used. The study was approved by the Internal Review Board of the North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System.

Cell Isolation and Culture

Monocytes were isolated from cord blood under pyrogen-free conditions at room temperature. Whole blood was layered over Ficoll-Paque PLUS (Amersham-GE Healthcare, Piscataway, N.J., USA) and centrifuged at 400 g for 40 min. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) layer was collected from the interphase and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco-Invitrogen, Grand Island, N.Y., USA). Residual erythrocytes were lysed by hypotonic buffer. PBMCs were washed with PBS 3 times and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (RPMI+; Gibco-Invitrogen) at 50 × 106 cells/ml. Monocytes were purified using Percoll (Amersham-GE Healthcare) solution as described previously [18]. PBMCs were layered over hyperosmotic Percoll solution and centrifuged at 580 g for 15 min. The monocyte-enriched fraction was collected at the interphase and washed 3 times with PBS. Monocytes were further purified by depletion of nonmonocytes using MACS monocyte isolation kit II supplemented with CD15 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, Calif., USA). Supplementing with CD15 microbeads helped reduce granulocyte contamination and increase final monocyte purity. Final monocyte purity was >90% as determined by flow cytometry. Monocytes were then resuspended at 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI+ and aliquoted at 1 ml into 48-well culture plates. For the dose response, monocytes were pre-incubated with PBS (vehicle control) and serial doses of IL-10 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn., USA) or DEX (Abraxis Pharmaceutical Products, Schaumburg, Ill., USA) for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, then stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml; L4391, from Escherichia coli 0111:B4; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo., USA) for 18 h. For the time course experiments, monocytes were pre-incubated with PBS, IL-10 monoclonal antibody (10 μg/ml), immunoglobulin (IgG) control (MAB2171, MAB004; R&D Systems) and equimolar concentration (10−8M) of IL-10 or DEX for 1 h, then stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for up to 18 h. The IL-10 monoclonal antibody concentration used in our experimental conditions was derived from an antibody titration assay using IL-8 release as an endpoint (data not shown). Transcription factor activity was assayed at 0.5, 4 and 18 h, and cytokines were assayed at 4 and 18 h of LPS stimulation. PMNs were isolated as described previously [7] and resuspended at 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI+. PMNs were exposed to serial doses of DEX for 1 h and then stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 18 h as above, serving as a positive control.

ELISA

TNF-α, IL-8, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-4 and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) were measured in cell culture supernatants using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems). The assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The volume of samples ranged from 50 to 200 μl. The minimal detectable doses for TNF-α, IL-8, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-4 and IL-1ra were 1.6, 3.5, 1, 3.9, 10 and 14 pg/ml, respectively.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

The nuclear extracts (1 × 106 cells) were prepared and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) assays were performed as described previously [19, 20]. Additional protease inhibitors used were 1× Complete (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind., USA), 2 mM diisopropylfluorophosphate (Sigma) and 200 μM MG132 (Biomol International, Plymouth Meeting, Pa., USA). The oligonucleotides used as probes were 42-base pair double-stranded custom construct 5′-TTGTTACAAG GGGACTTTCC GCTG GGGACTTTCC AGGGAGGC-3′ (Invitrogen) for NF-κB (tandem repeats of NF-κB-binding sites underlined), and consensus oligos for AP-1 and STAT3 (sc-2501, sc-2571; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif., USA). The oligonucleotides used for competition assays were mutant construct 5′-TTGTTACAAT CTCACTTTCC GCTT CTCACTTTCC AGGGAGGC-3′ for NF-κB, and mutant oligos for AP-1 and STAT3 (sc-2514, sc-2572; Santa Cruz).

Western Blotting

Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from 1 × 106 cells as described previously, including the additional inhibitors listed above [19, 20]. Cytoplasmic extracts and washed nuclear pellets were boiled with sample buffer (SDS reducing buffer; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif., USA) to denature proteins. Denatured proteins were separated on 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond-ECL; Amersham-GE Healthcare). For the detection of phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3), membranes were blocked overnight with 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (Sigma) in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 140 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% Tween 20 solution (TBST-BSA) before incubating with primary antibody against pSTAT3 (sc-8059; Santa Cruz) for 2 h at room temperature, diluted 1:200 in TBST-BSA. After washing with TBST, membranes were incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody, diluted 1:20,000 in TBST-BSA. For blocking and incubations with antibodies, TBST-BSA was supplemented with 0.01% (v/v) of each phosphatase inhibitor cocktails A and B (Santa Cruz). For the detection of total STAT3, membranes were blocked with TBST containing 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk, before incubating with primary antibodies against STAT3 (sc-8019; Santa Cruz) for 2 h at room temperature, diluted 1:200. After washing, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies as above, diluted 1:2,000. Labeled proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents as described by the manufacturer (ECL PLUS, Amersham-GE Healthcare).

Data Analysis

The EMSA images were scanned and analyzed by densitometry using image analysis software UN-SCAN-IT gel v. 5.1 (Silk Scientific, Orem, Utah, USA). Data were expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons by GraphPad InStat version 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif., USA).

Results

PI Cytokine Release

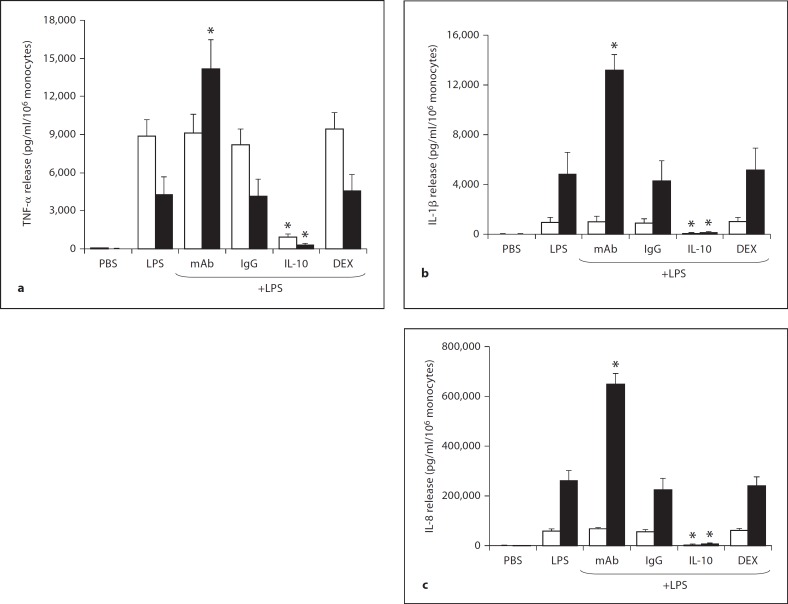

Figure 1 depicts the release of 3 PI cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-8) from LPS-stimulated monocytes of the newborn at 4 and 18 h. TNF-α levels from cells stimulated with LPS alone were higher at 4 compared to 18 h, while the reverse was observed for IL-1β and IL-8. IL-8 levels were greatly increased compared to TNF-α and IL-1β when these cytokines were measured from medium with the same number of cells. On a molar basis, IL-8 increased 134- and 116-fold at 18 h over TNF-α and IL-1β, respectively. For all 3 PI cytokines, exogenous IL-10 significantly reduced release compared to LPS alone; inhibition was 89.4, 91.4 and 92.3% at 4 h and 92.8, 97.4 and 97.4% at 18 h for TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-8, respectively. There was no reduction in PI cytokine release by an equimolar (10−8M) level of DEX at 4 and 18 h of LPS stimulation. Release of all PI cytokines 18 h after stimulation with LPS was significantly increased by a monoclonal antibody against IL-10, specifically 233, 173 and 150%, for TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-8, respectively. The specificity of this antibody for IL-10 was supported by the results that the control pre-immune IgG exhibited the same release of PI cytokines at 18 h as LPS alone. Interestingly, the release of PI cytokines 4 h after stimulation was not enhanced by the IL-10 monoclonal antibody, suggesting that the endogenous IL-10 is released from LPS-stimulated monocytes at later time points.

Fig. 1.

PI cytokine release from endotoxin (LPS)-stimulated monocytes (n = 5) of the newborn at 4 h (□) and 18 h (▪): effects of monoclonal antibody (mAb) to endogenous IL-10, IgG control for the monoclonal antibody, exogenous IL-10 and DEX. TNF-α (a), IL-1β (b) and IL-8 (c) release are shown. * p < 0.01 versus LPS alone at the same time point.

AI Cytokine Release

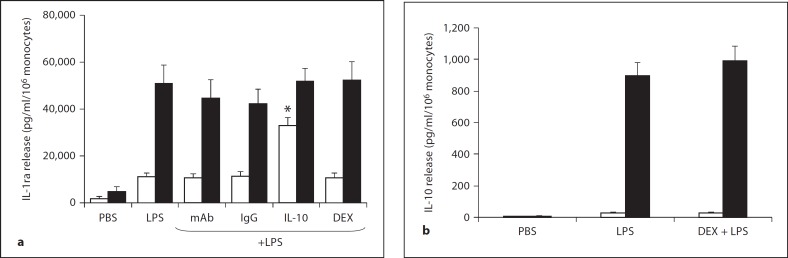

Figure 2 depicts the release of 2 AI cytokines, IL-1ra and IL-10, from LPS-stimulated monocytes of the newborn. IL-4 was not detectable under the same study conditions and therefore the data is not shown. Figure 2a shows that IL-1ra release is detectable at 4 h and to a greater extent at 18 h of LPS stimulation. The molar concentration of IL-1ra at 18 h was 2 × 10−9M compared to 2.8 × 10−10M for the PI cytokine IL-1β. IL-1ra release was unaffected by DEX (10−8M), IL-10 monoclonal antibody or the IgG control. However, exogenous IL-10 (10−8M) significantly increased IL-1ra release by 4 h. Figure 2b demonstrates that LPS stimulated the release of IL-10 to a level of approximately 900 pg/ml/106 monocytes by 18 h; this is a concentration of 5 × 10−11M for IL-10. DEX had no effect on IL-10 release at 4 and 18 h.

Fig. 2.

AI cytokine release from endotoxin (LPS)-stimulated monocytes (n = 5) of the newborn at 4 h (□) and 18 h (▪): effects of monoclonal antibody (mAb) to endogenous IL-10, IgG control for the monoclonal antibody, exogenous IL-10 and DEX. IL-1ra (a) and IL-10 (b) are shown. * p < 0.01 versus LPS alone at the same time point.

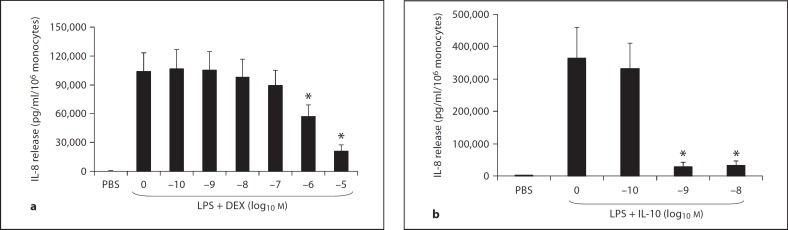

Effect of Exogenous IL-10 and DEX on IL-8 Release: Dose Responses

Figure 3 demonstrates the dose response to DEX and IL-10 on an equimolar basis, with regard to the inhibition of IL-8 release from LPS-stimulated monocytes over 18 h. IL-10 significantly reduced IL-8 release by 92.2 and 91.2% at 10−9 and 10−8M, respectively, compared to LPS alone. On the other hand, no inhibition by DEX was observed below 10−6M. DEX inhibited IL-8 release by 45 and 80% for 10−6 and 10−5M, respectively. As a positive control for the effect of DEX (10−8M) on monocytes, we simultaneously measured IL-8 release from PMNs of the newborn stimulated by LPS for 18 h. As previously shown [5], DEX inhibited IL-8 release in PMNs by 83% (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

IL-8 release from endotoxin (LPS)-stimulated monocytes (n = 5) of the newborn at 18 h: dose response to DEX (a) and IL-10 (b) on a molar basis. * p < 0.05 versus LPS alone.

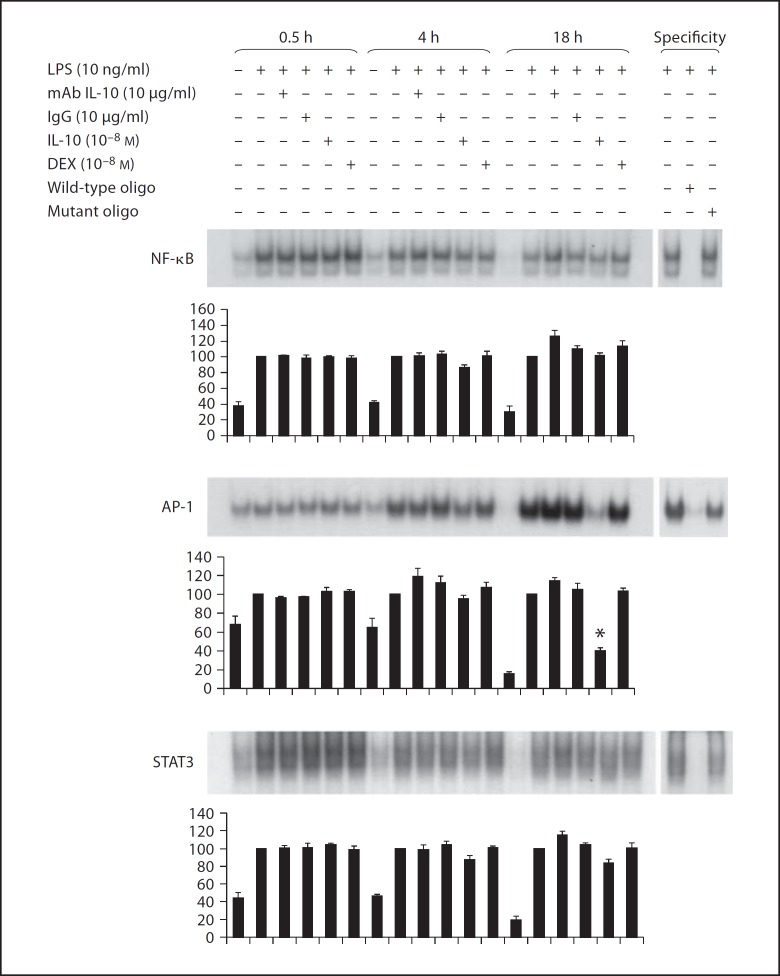

Transcription Factor Activity

Figure 4 demonstrates DNA-binding activity from nuclear extracts of LPS-stimulated monocytes at 0.5, 4 and 18 h under different experimental conditions. Below each representative EMSA images, the densitometric analyses of 5 experiments are shown. Densitometric values were statistically analyzed by comparing experimental conditions to the LPS-stimulated sample within each time point. Specificity of the EMSA for the respective transcription factor was analyzed by using unlabeled oligonucleotides (right panels). The top EMSA image demonstrates persistent, but waning NF-κB DNA-binding activity over 18 h of LPS stimulation. Neither the EMSA images nor the densitometry demonstrate any effects of IL-10 (10−8M), DEX (10−8M) or IL-10 monoclonal antibody on NF-κB DNA-binding activity. The middle EMSA image demonstrates increasing AP-1 DNA binding during LPS stimulation over 18 h. A 60% inhibition of AP-1 DNA binding was observed on the EMSA image and by densitometry with exogenous IL-10 (10−8M) at 18 h. AP-1 DNA binding was unaffected by DEX (10−8M) or IL-10 monoclonal antibody. The bottom EMSA image shows that total STAT3 DNA-binding activity was greater at 0.5 h than at 4 and 18 h. The densitometry analysis revealed no effect of IL-10 (10−8M), DEX (10−8M) or IL-10 monoclonal antibody on the STAT3 DNA-binding activity in LPS-stimulated monocytes.

Fig. 4.

Representative EMSAs and densitometry from all experiments (n = 5) for NF-κB, AP-1 and STAT3. EMSA was analyzed in nuclear extracts of monocytes stimulated by endotoxin (LPS) at 0.5, 4 and 18 h. At each time point the effects of monoclonal antibody to endogenous IL-10 (mAb IL-10), IgG control for the monoclonal antibody, exogenous IL-10 and DEX are shown. Statistical analyses of densitometric values were compared to LPS alone at each time point, which was considered 100%. Wild-type oligonucleotides (oligo) and mutant oligonucleotides were used to demonstrate DNA-binding specificity.

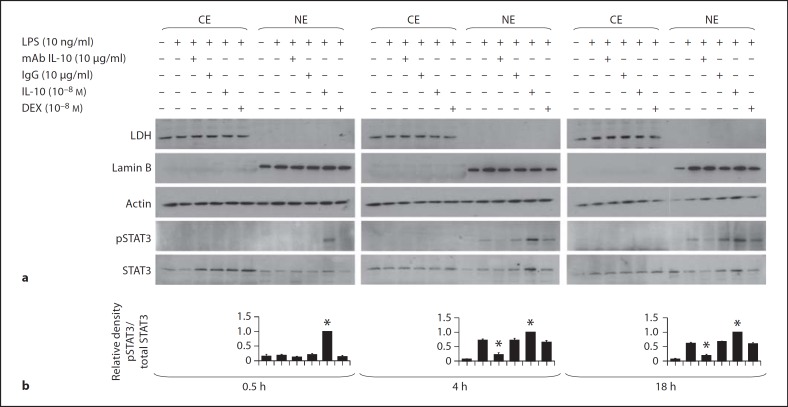

pSTAT3

Figure 5a illustrates a representative Western blot analysis (n = 5) of pSTAT3 protein levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of monocytes stimulated by LPS. pSTAT3 was not detected in the cytoplasm under any condition or time point. pSTAT3 was detected in nuclear extracts of LPS stimulated monocytes at 4 and 18 h after stimulation. This STAT3 phosphorylation at 4 and 18 h was markedly reduced by IL-10 antibody. Conversely, exogenous IL-10 increased the STAT3 phosphorylation at the 0.5, 4 and 18 h time points. DEX had no effect on pSTAT3 levels. Figure 5b illustrates the densitometric evalution of the above Western blot analyses of pSTAT3/total STAT3 levels measured in the nuclear extracts (n = 5).

Fig. 5.

a A representative Western blot of pSTAT3 from cytoplasmic (CE) and nuclear extracts (NE) of endotoxin (LPS)-stimulated monocytes (n = 5) of the newborn at 0.5, 4 and 18 h: effects of monoclonal antibody to endogenous IL-10 (mAb IL-10), IgG control for the monoclonal antibody, exogenous IL-10 and DEX. Cytoplasmic contamination of the nuclear fraction was monitored using lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) antibody, and the presence of nuclear proteins in the cytoplasmic fraction was assessed using lamin B antibody. Equal protein loading was confirmed using actin antibody. b Densitometric evaluation of pSTAT3 levels in the nuclear extracts of monocytes. The pSTAT3 levels in nuclear extracts were scanned and the densities were normalized to densities of total STAT3. The values for LPS + IL-10 at each time point were arbitrarily set to 1, and the values for the other conditions are presented relative to the set value. The data represent the means of 5 independent experiments ± SEM. * p < 0.01 versus LPS alone.

Discussion

The overall aim of this study was to determine mechanisms of cytokine regulation by the monocyte of the newborn that may lead to new AI therapy for serious perinatal disorders in term and preterm infants [1, 13, 21]. The present in vitro studies used a highly purified, cord blood monocyte preparation with LPS as a stimulant for cytokine release and transcription factor activity studies. Cord blood monocytes were purposely isolated from the placentas of healthy term infants, to avoid the confounding influences of prenatal steroids, clinical chorioamnionitis, maternal conditions leading to an indicated deliv- ery and maternal medications. Accordingly, the results of our studies may not be accurately extrapolated to very premature infants. Although a subset of newborns that develop inflammatory conditions, such as BPD, may have an associated exposure to microbial toxins, other factors such as oxidative stress and ventilator-induced lung injury need to be considered.

In the present study, LPS-stimulated monocytes released TNF-α, with highest levels at 4 h, compared with IL-1β and IL-8 with highest levels at 18 h. Corrected for cell number, the monocytes of the newborn released a much greater amount of these PI cytokines compared to the PMN of the newborn [7]. LPS-stimulated monocytes released the AI cytokines IL-1ra and IL-10, with highest levels at 18 h, as opposed to 4 h. IL-4, an AI cytokine, was not detectable after LPS stimulation. Endogenous IL-10 release was in the range of 10−10 to 10−11M. We then examined whether endogenous IL-10 release by monocytes had a negative feedback effect on PI cytokine release. This was verified by adding an IL-10 monoclonal antibody to LPS-stimulated monocytes, resulting in significantly elevated PI cytokine release by 18 h for all 3 PI cytokines assayed. Previous work from adults has also demonstrated this regulatory role of IL-10 in macrophages stimulated by pathogens or their products [22].

Surprisingly, when monocytes were pre-incubated with therapeutic levels of DEX for BPD (10−8M), there was no inhibition of PI cytokine release. In fact, no significant effect was observed until 10−6M. Marked inhibition of IL-8 by DEX from neutrophils served as a positive control. DEX also had no effect on AI cytokine release. On the other hand, IL-10 at 10−8M markedly inhibited monocyte release of all 3 PI cytokines.

Dose-response studies demonstrated that IL-10 at 10−9M almost completely inhibited IL-8, which served as marker for PI cytokines. Therefore, the results of the present study indicate that endogenous IL-10 release in the 10−10 to 10−11M range has a modulating effect on monocyte PI cytokine release, and approximately a 100-fold increase above endogenous levels would be needed to markedly inhibit PI cytokine release and have a therapeutic AI effect. Endogenous IL-10 is either undetectable or detectable at very low levels in the airways of preterm and term newborns at risk for BPD [23,24,25,26]. The present study with monocytes and the previous study with identical conditions for PMNs [7] suggest that exogenous IL-10 at 10−8M could have therapeutic potential for BPD [7, 27]. The relative resistance of the LPS-stimulated monocyte of the newborn to DEX compared to exogenous IL-10 at known therapeutic levels of DEX may suggest a developmental cause or a glucocorticoid receptor resistance to DEX as opposed to other corticosteroids [28].

IL-10 has been used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis in adults [29]. IL-10 is generally considered an AI cytokine. However, elevated levels of IL-10 have been detected in a minority of preterm infants during early development of BPD [26], sepsis [30] and acute respiratory distress syndrome [31]. It is unclear if the elevated IL-10 levels measured under these conditions are only counterregulatory for excessive PI cytokine release.

The transcription factor STAT3 is required for IL-10 AI actions. Possible mechanisms of STAT3 activity include the posttranslational modification of PI transcription factor structure, modification of chromatin attachment to transcription factors, or sequestration of transcription factors away from their PI promoters [22]. In monocytic cells, NF-κB is found in the cytoplasm as an inactive NF-κB-inhibitor-κB (IκB) complex. A stimulus such as LPS, via its Toll-like receptor and signal transduction pathway, activates IκB kinase to phosphorylate IκB, freeing NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus and initiate transcription on a persistent basis [32]. AP-1 is a group of transcription factors composed of dimeric proteins activated by the extracellular signal-regulated kinase subgroup of mitogen-activated protein kinases [33]. NF-κB and AP-1 modulate the activity of each other [34]. IL-10 and STAT3, like glucocorticoids and the glucocorticoid receptor, may also have a mechanism of action involving a complex interaction between multiple transcription factors [16].

In the present study, nuclear extracts from LPS-stimulated monocytes exhibited a waning but persistent DNA-binding activity of NF-κB, increasing activity of AP-1 and a persistent activity of STAT3 at the 0.5, 4 and 18 h time points, using EMSAs. There was no effect of DEX (10−8M), which is in concordance with the lack of DEX inhibition of PI cytokine release. IL-10 did not inhibit NF-κB DNA binding in contrast to work in PBMCs from adults [35]. PBMCs are a mixture of lymphocytes predominantly along with monocytes, making comparisons between studies invalid. However, in monocytes of the newborn, exogenous IL-10 caused a striking reduction in AP-1 activity over 18 h of LPS stimulation. At the same time, this was associated with increased levels of nuclear pSTAT3. Part of this increase in pSTAT3 was related to endogenous IL-10. When IL-10 monoclonal antibody was added to LPS-stimulated monocytes, a reduction in nuclear pSTAT3 was observed.

In summary, with a focus on the LPS-stimulated monocytes of the healthy term newborn, we demonstrated that endogenous IL-10 provides a negative feedback mechanism for PI cytokine release and exogenous IL-10 is a potent inhibitor of PI cytokine release. The mechanism of the AI action of IL-10 involves an increase in nuclear pSTAT3 levels associated with a reduction in AP-1 DNA binding. We speculate that the observed DEX insensitivity of the monocyte may partly explain the variable response to DEX in the treatment of BPD [12, 13]. It would be of interest to determine whether the insensitivity to DEX in cells derived from monocytes (that is, macrophages, microglial cells and Kupffer cells) also occurs. Exploring the AI pathways of IL-10 and corticosteroids at the molecular level could lead to new therapy for serious inflammatory disorders with collateral healthy tissue damage in the newborn.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) NIH grant No. 5R03HD048508-02.

References

- 1.Gotsch F, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Mazaki-Tovi S, Pineles BL, Erez O, Espinoza J, Hassan SS. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50:652–683. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31811ebef6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viscardi RM, Muhumuza CK, Rodriguez A, Fairchild KD, Sun CC, Gross GW, Campbell AB, Wilson PD, Hester L, Hasday JD. Inflammatory markers in intrauterine and fetal blood and cerebrospinal fluid compartments are associated with adverse pulmonary and neurologic outcomes in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:1009–1017. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000127015.60185.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merritt TA, Cochrane CG, Holcomb K, Bohl B, Hallman M, Strayer D, Edwards DK, III, Gluck L. Elastase and α1-proteinase inhibitor activity in tracheal aspirates during respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:656–666. doi: 10.1172/JCI111015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson JC, Chi EY, Wilson CB, Truog WE, Teh EC, Hodson WA. Sequence of inflammatory cell migration into lung during recovery from hyaline membrane disease in premature newborn monkeys. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:937–940. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.4.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speer CP. Inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a continuing story. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen-Pupp I, Hallin AL, Hellstrom-Westas L, Cilio C, Berg AC, Stjernqvist K, Fellman V, Ley D. Inflammation at birth is associated with subnormal development in very preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:183–188. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318176144d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson D, Miskolci V, Clark DC, Dolmaian G, Vancurova I. Interleukin-10 production after pro-inflammatory stimulation of neutrophils and monocytic cells of the newborn: comparison to exogenous interleukin-10 and dexamethasone levels needed to inhibit chemokine release. Neonatology. 2007;92:127–133. doi: 10.1159/000101432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer BW, Jobe AH, Ikegami M. Monocyte function in preterm, term and adult sheep. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:52–57. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000066621.11877.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer BW, Ikegami M, Moss TJ, Nitsos I, Newnham JP, Jobe AH. Antenatal betamethasone changes cord blood monocyte responses to endotoxin in preterm lambs. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:764–768. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000120678.72485.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis DB, Wilson CB. Developmental immunology and role of host defenses in fetal and neonatal susceptibility too infection. In: Remington J, Klein J, Baker C, Wilson C, editors. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. ed 6. Philadelphia: Else-vier-Saunders; 2006. pp. 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing L, Remick DG. Relative cytokine and cytokine inhibitor production by mononuclear cells and neutrophils. Shock. 2003;20:10–16. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000065704.84144.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee on Fetus and Newborn Postnatal corticosteroids to treat or prevent chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2002;109:330–308. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watterberg K. Anti-inflammatory therapy in the neonatal intensive care unit: present and future. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schild PN, Charles BG. Determination of dexamethasone in plasma of premature neonates using high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1994;658:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lugo RA, Nahata MC, Menke JA, McClead RE., Jr Pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone in premature neonates. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;49:477–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00195934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kassel O, Herrlich P. Crosstalk between the glucocorticoid receptor and other transcription factors: molecular aspects. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;275:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray PJ. STAT3-mediated anti-inflammatory signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:1028–1031. doi: 10.1042/BST0341028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Repnik U, Knezevic M, Jeras M. Simple and cost-effective isolation of monocytes from buffy coats. J Immunol Methods. 2003;278:283–292. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00231-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vancurova I, Miskolci V, Davidson D. NF-κB activation in tumor necrosis factor α-stimulated neutrophils is mediated by protein kinase Cδ: correlation to nuclear IκBα. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19746–19752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castro-Alcaraz S, Miskolci V, Kalasapudi B, Davidson D, Vancurova I. NF-κB regulation in human neutrophils by nuclear IκBα: correlation to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2002;169:3947–3953. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berry SM, Romero R, Gomez R, Puder KS, Ghezzi F, Cotton DB, Bianchi DW. Premature parturition is characterized by in utero activation of the fetal immune system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1315–1320. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91378-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray PJ. Understanding and exploiting the endogenous interleukin-10/STAT3-mediated anti-inflammatory response. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones CA, Cayabyab RG, Kwong KY, Stotts C, Wong B, Hamdan H, Minoo P, deLemos RA. Undetectable interleukin (IL)-10 and persistent IL-8 expression early in hyaline membrane disease: a possible developmental basis for the predisposition to chronic lung inflammation in preterm newborns. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:966–975. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199606000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McColm JR, Stenson BJ, Biermasz N, McIntosh N. Measurement of interleukin-10 in bronchoalveolar lavage from preterm ventilated infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;82:F156–F159. doi: 10.1136/fn.82.2.F156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beresford MW, Shaw NJ. Detectable IL-8 and IL-10 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from preterm infants ventilated for respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2002;52:973–978. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200212000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garingo A, Tesoriero L, Cayabyab R, Durand M, Blahnik M, Sardesai S, Ramanathan R, Jones C, Kwong K, Li C, Minoo P. Constitutive IL-10 expression by lung inflammatory cells and risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:197–202. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e31802d8a1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwong KY, Jones CA, Cayabyab R, Lecart C, Khuu N, Rhandhawa I, Hanley JM, Ramanathan R, deLemos RA, Minoo P. The effects of IL-10 on proinflammatory cytokine expression (IL-1β and IL-8) in hyaline membrane disease (HMD) Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;88:105–113. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis-Tuffin LJ, Cidlowski JA. The physiology of human glucocorticoid receptor beta (hGRβ) and glucocorticoid resistance. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1069:1–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1351.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asadullah K, Sterry W, Volk HD. Interleukin-10 therapy-review of a new approach. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:241–269. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oberholzer A, Oberholzer C, Moldawer LL. Interleukin-10: A complex role in the pathogenesis of sepsis syndrome and its potential as an anti-inflammatory drug. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S58–S63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsons PE, Moss M, Vannice JL, Moore EE, Moore FA, Repine JE. Circulating IL-1ra and IL-10 levels are increased but do not predict the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in at-risk patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1469–1473. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.4.9105096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miskolci V, Rollins J, Vu HY, Ghosh CC, Davidson D, Vancurova I. NFκB is persistently activated in continuously stimulated human neutrophils. Mol Med. 2007;13:134–142. doi: 10.2119/2006-00072.Miskolci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E131–E136. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujioka S, Niu J, Schmidt C, Sclabas GM, Peng B, Uwagawa T, Li Z, Evans DB, Ab- bruzzese JL, Chiao PJ. NF-κB and AP-1 connection: mechanism of NF-κB-dependent regulation of AP-1 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7806–7819. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7806-7819.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang P, Wu P, Siegel MI, Egan RW, Billah MM. Interleukin (IL)-10 inhibits nuclear factor κB (NF κB) activation in human monocytes. IL-10 and IL-4 suppress cytokine synthesis by different mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9558–9563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]