Abstract

The exacerbation of musculoskeletal pain by stress in humans is modeled by the musculoskeletal hyperalgesia in rodents following a forced swim. We hypothesized that stress-sensitive corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) receptors and transient receptor vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptors are responsible for the swim stress-induced musculoskeletal hyperalgesia. We confirmed that a cold swim (26°C) caused a transient, morphine-sensitive decrease in grip force responses reflecting musculoskeletal hyperalgesia in mice. Pretreatment with the CRF2 receptor antagonist astressin 2B, but not the CRF1 receptor antagonist NBI-35965, attenuated this hyperalgesia. Desensitizing the TRPV1 receptor centrally or peripherally using desensitizing doses of resiniferatoxin (RTX) failed to prevent the musculoskeletal hyperalgesia produced by cold swim. SB-366791, a TRPV1 antagonist, also failed to influence swim-induced hyperalgesia. Together these data indicate that swim stress-induced musculoskeletal hyperalgesia is mediated, in part, by CRF2 receptors but is independent of the TRPV1 receptor.

Keywords: CRF, Forced swim, Hyperalgesia, RTX, Stress, TRPV1, Urocortin

1. Introduction

Human and animal models demonstrate that stress can induce hyperalgesia (Imbe et al., 2006). In rats, the stress of a cold forced swim enhances thermal nociception measured using the hot plate assay (Quintero et al., 2000; Suarez-Roca et al., 2006a; Suarez-Roca et al., 2006b), chemical nociception measured using the formalin test (Imbe et al., 2010; Quintero et al., 2011; Quintero et al., 2003; Suarez-Roca et al., 2008), and musculoskeletal nociception measured using the grip force assay (Okamoto et al., 2012; Suarez-Roca et al., 2006a). Consistent with this, cold swim also increases neuronal activity in the spinal cord as indicated by increases in c-Fos (Quintero et al., 2003; Suarez-Roca et al., 2008).

The mechanism(s) that produce acute stress-induced hyperalgesia remain unclear and must be elucidated if we are to eventually understand the even more important influence of chronic stress on musculoskeletal pain. A variety of models to induce stress or anxiety have been previously examined. One potential contributor to anxiety-induced hyperalgesia is cholecystokinin (CCK) which works in a pro-nociceptive fashion by inhibiting a descending antinociceptive pathway involving the periaqueductal grey (PAG) (reviewed by Lovick (Lovick, 2008)). GABA activity in the spinal cord appears to be essential for novelty stress-induced hyperalgesia (Vidal and Jacob, 1986) whereas noradrenaline is essential to acute anxiety-induced hyperalgesia (Jorum, 1988). Forced swim-induced hyperalgesia in rats lasts up to 9 days and is postulated to result from activity in the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) (Imbe et al., 2010), or decreased release of GABA in the spinal cord resulting in increased N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) activity in the cord (Quintero et al., 2011). In addition to these events, one may reasonably posit that stress influences pain by the release of stress hormones. Consistent with this, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), the primary mediator of mammalian neuroendocrine stress responses, and its analogs, urocortin I, II and III, are not only distributed along the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, but also in pain-relevant sites in the central nervous system (CNS) (Fekete and Zorrilla, 2007; Korosi et al., 2007; Lariviere and Melzack, 2000). Together the CRF1 and CRF2 receptors have been found to shape behavioral and neurochemical responses to stress and frequently have opposite effects (reviewed by Coste et al. (Coste et al., 2001; Reul and Holsboer, 2002) and Reul and Holsboer (Coste et al., 2001; Reul and Holsboer, 2002). CRF influences nociception (reviewed by Lariviere and Melzack (Lariviere and Melzack, 2000)), presumably by interacting with CRF receptors. Another model of hyperalgesia has demonstrated that an increase in footshock-induced urinary bladder hypersensitivity was attenuated by a CRF2 receptor antagonist at the spinal level in rats (Robbins and Ness, 2008). Thus, it would be of interest to determine whether these receptors also contribute to the stress-induced modulation of musculoskeletal nociception.

Based on the ability of CRF to modulate nociception, we hypothesized that stress leads to hyperalgesia by the activation of CRF1 and/or CRF2 receptors in the spinal cord. We tested this hypothesis using an acute forced swim as a widely used and easily reproducible stressor and grip force as a measure of musculoskeletal nociception that has proven sensitive to stress-induced hyperalgesia in rats (Imbe et al., 2010). Involvement of CRF receptors was examined using NBI-35965, a CRF1 receptor antagonist, and astressin 2B, a CRF2 receptor antagonist.

Skeletal muscles are innervated by the same category of primary afferent C- and A∂-fibers as those used in the transmission of other nociceptive stimuli (Cavanaugh et al., 2009; Mense, 1992; O'Connor and Cook, 1999). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptors exert pro-nociceptive effects by activation of primary afferent C-fibers (Hoheisel et al., 2004) and Aδ- fibers (Churyukanov et al., 2012) innervating both skin and muscle (Hoheisel et al., 2004; Holzer, 1988; Light et al., 2008; Szallasi et al., 2007). While TRPV1 ligands have been found to have no effect on mechanical sensitivity in some models (Bishnoi et al., 2011a; Bishnoi et al., 2011b), TRPV1 is crucial to the enhancement of nociception in many models of hyperalgesia (Chung et al., 2011; Fujii et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 2011; Szabo et al., 2005). To determine whether swim stress-induced musculoskeletal hyperalgesia is mediated by TRPV1 activity, we examined the sensitivity of stress-induced hyperalgesia to pretreatment with resiniferatoxin (RTX), a compound that desensitizes TRPV1 sites (Farkas-Szallasi et al., 1996; Goso et al., 1993; Iadarola and Mannes, 2011; Kissin and Szallasi, 2011; Szallasi and Blumberg, 1992; Szallasi et al., 1989) and to pretreatment with SB-366791, an antagonist at TRPV1 receptors (Varga et al., 2005).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult female Swiss Webster mice weighing 20–25 g (Harlan Sprague Dawley, INC; Indianapolis, IN) were housed five per cage and allowed to acclimate for at least one week prior to use. Mice were allowed free access to food and water, and housed in a room with a constant temperature of 23°C on a 12-h light–dark cycle. Females were initially used to reflect the higher prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in most anatomic sites in females than in males when studied in humans (Wijnhoven et al., 2006). We continued using females for the sake of comparison, however, we found no difference between the degree of hyperalgesia induced by the forced swim in male mice compared to female mice. Because sex differences were not apparent and not the focus of our study, the estrus cycle of each mouse was not examined. All procedures were performed according to the guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), the University of Minnesota Animal Care and Use Committee, and the Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council (DHEW Publication NIH 78-23, revised 1995). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, to reduce the number of animals used, and to utilize alternatives to in vivo techniques, if available.

2.2. Drugs and chemicals

Resiniferatoxin (RTX), a TRPV1 ligand and desensitizer, was obtained from LC Laboratories, Inc. (Woburn, MA), dissolved in 10% ethanol, 10% Tween and 80% saline solution (pH 5.5–6.0), and delivered intrathecally (i.t.) at a dose of 0.125 µg in a 5 µl volume or diluted in sesame oil (pH 4.5–5.0) and given subcutaneously (s.c.) at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg. In preliminary studies, we found this dose and route to cause antinociception in the tail flick assay, suggesting desensitization of TRPV1 sites along thermal nociceptive pathways. Morphine sulfate, a µ opioid receptor agonist, was purchased from Mallinckrodt (St. Louis, MO). Morphine sulfate was dissolved in saline (pH 5.0) and injected i.p. at 10 mg/kg, a dose that induces a potent antinociception in the tail flick assay in mice. Injections made intrathecally in mice were delivered at approximately the L5-L6 intravertebral space using a 30-gauge, 0.5 inch disposable needle on a 50 µL Luer tip Hamilton syringe in lightly restrained, unanaesthetized mice (Hylden and Wilcox, 1980). NBI-35965 hydrochloride and astressin 2B were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO) and were dissolved in double-distilled water (pH 4.0–4.5) and were injected in an amount of 5 µl i.t. The doses of the antagonists (50 µg NBI-35965, 20 µg astressin 2B) that we used have been previously shown to be centrally active (Martinez et al., 2004). SB-366791, a TRPV1 antagonist, was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY) and injected i.p. (0.5 mg/kg), at a dose that effectively inhibited the number of eye wipe responses produced by intraocular capsaicin and blocked capsaicin-induced hypothermia in rats (Varga et al., 2005), or i.t. (30 µg/mouse), at a dose that attenuated the bilateral hyperalgesia produced by intraplantar injection of TNFα (Fernandes et al., 2011). SB-366791 was dissolved in the lowest concentration of DMSO necessary to dissolve the drug [40% DMSO (pH 5.5–6.0) for i.p. injections and 70% when injected centrally] and injected 30 min before the forced swim for i.p. injections or 15 min before the swim after i.t. or i.c.v. injections. For each drug treatment, control mice were injected with the same amount of vehicle.

2.3. Forced swim test

The forced swim test was used to expose mice to acute stress (Porsolt, 1979; Porsolt et al., 1979; Porsolt et al., 1977; Suarez-Roca et al., 2006a; Suarez-Roca et al., 2006b). Each mouse was put individually into a large, 2-liter beaker (diameter: 15 cm, height: 20 cm) containing water maintained at 26°C or 41°C. Mice were forced to swim for 5, 15 or 30 min. The water level was deep enough (18 cm) so the tail of the mouse never touched the bottom. After the swim, mice were removed from the water and rectal body temperature, grip force and latency of the tail flick were monitored during recovery.

2.4. Grip force assay

Forelimb grip force was measured using a grip force apparatus as described in rats (Kehl et al., 2000) and mice (Kehl et al., 2003; Kovacs et al., 2008). The grip force apparatus consists of a force transducer that is connected to a wire mesh grid (12 × 7 cm2 O.D. with a 0.5-cm square wire grid) and positioned on top of an aluminium frame approximately 30 cm above the bench top. During testing, each mouse was held by its tail and gently passed in a horizontal direction over the wire grid until it grasped the grid with its forepaws. The peak force that was exerted by the forelimbs of each mouse when pulling on the grid was recorded by the force transducer, to which the grid is attached. Two grip force measures were obtained at each time-point; the average of these measurements was used to represent each animal’s forelimb grip force at that particular time. Animals were familiarized with the grip force apparatus for three days by daily grip force testing prior to initiation of the experiment. On the third day, grip force measurements were obtained prior to each intervention to establish baseline values for each animal. Then the drug was administered and grip force measured at the times indicated. Grip force data are represented as raw data and expressed in terms of grams (g).

2.5. Tail flick assay

Animals were manually restrained and the tail submerged to a distance of 1 cm from the base of the tail in a water bath maintained at 51°C. The withdrawal latency was defined as the time required for the animal to withdraw its tail from the water. To avoid tissue damage, cut-off times of 15 s were utilized.

2.6. Body temperature measurement

Body temperature measurement took place in a room with an ambient temperature of 25°C. The animal was removed from its cage, cupped on the counter under an open hand, and its colonic temperature measured using a rectal thermometer (ETI Microtherma 2K Thermometer connected to a RET-3 rectal probe). Tail temperatures were measured using a 153 IRB portable infra red thermometer which allowed measurement of tail temperatures without restraint by simply placing the probe near but not touching the surface of the skin.

2.7. Behavioral data analysis

Mean values (± S.E.M.) are presented throughout the figures. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using a Student's paired or unpaired t test between two groups or one- or two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Newman-Keuls or Bonferroni test respectively for comparison between multiple groups tested at the same time, as indicated. A difference was considered significant if the probability that it occurred because of chance alone was less than 5% (P<0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of cold swim stress on nociception

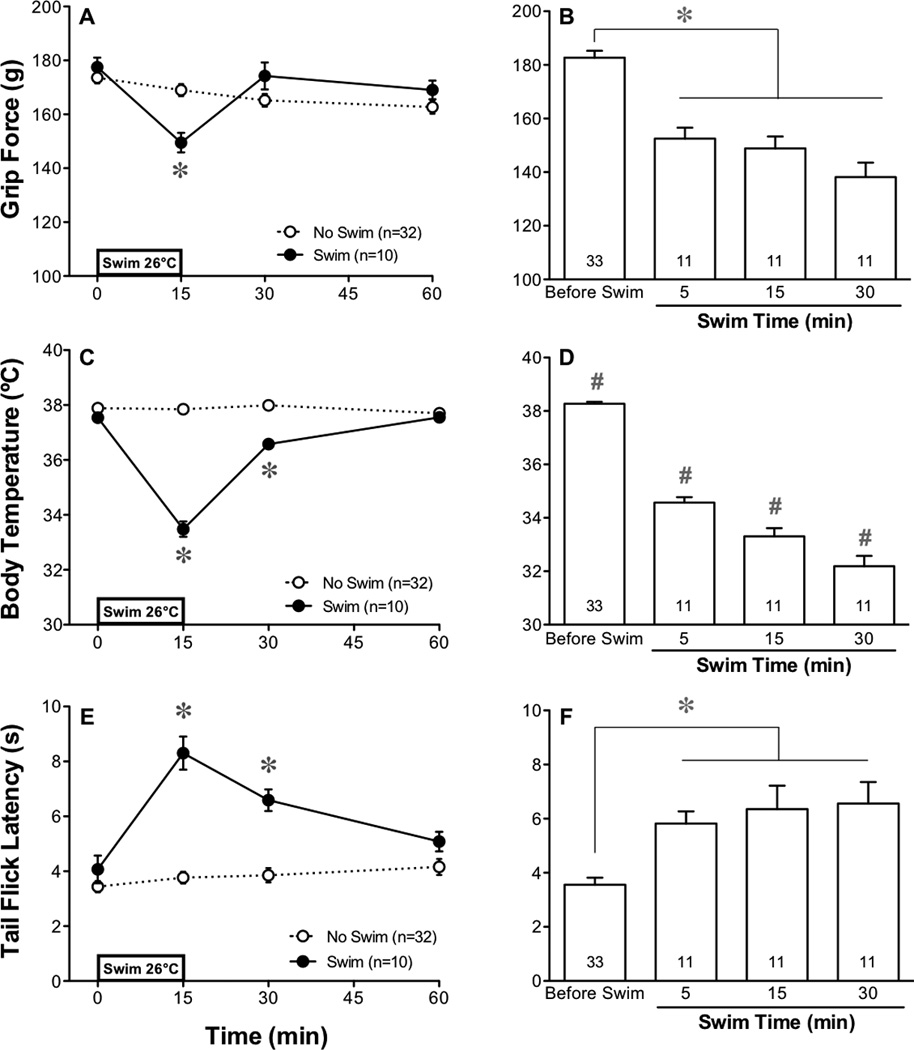

Immediately after a 15-min forced swim at 26°C, the mean grip force of mice decreased compared to their original pre-swim control values (0 min) as well as compared to the control group that was not exposed to the swim (Figure 1A–B). The magnitude of the decrease was only slightly influenced by the duration of the swim as a 5-min swim produced an effect similar to a 30-min swim, indicating a rapid onset of near maximal hyperalgesia. After the swim, the duration of hyperalgesia was transient as grip force responses returned to values no different than controls by 15 min after the termination of a 15-min swim (Figure 1A).

Fig. 1.

Effect of a cold swim stress on musculoskeletal nociception, body temperature and tail flick latency. Swim stress (15-min at 26°C) decreased grip force (A) simultaneously with a decrease in core body temperature (C) and an increase in tail flick latency (E) when measured before and at 0, 15 and 45 min after the end of the swim. Panels on the right depict the effect of a cold swim of different durations (5, 15 and 30 min) on grip force responses (B), body temperature (D) and tail flick latencies (F). Throughout the figures, SEM is calculated for all points but not shown by our graphical representation when smaller than the width of the symbol. Statistical analyses of each panel were performed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis. The asterisk indicates P<0.05 when the swim group was compared to the no swim group at a specific time before or after the swim (A,C,E). The effect immediately after swims of 3 different durations were compared to each group’s values before the swim using a paired Student’s t-test and then control values were pooled for graphical representation (B,D,F). The number sign further indicates P<0.05 when a group was different from all other values in that panel when compared using ANOVA, as described above. Throughout the figures, the number of animals used in each group is indicated in the key or at the base of each bar.

The rectal temperature of mice at the end of either a 5-, 15- or 30-min swim decreased in a fashion that depended on the duration of the swim (Figure 1D). Recovery to normal body temperatures was complete by 45 min after termination of the 15-min swim (Figure 1C).

In contrast to the hyperalgesic effect of the forced swim on grip force values, tail flick latencies of mice increased immediately following a cold 15-min swim and this effect persisted for 15 min (Figure 1E). Similar to the hyperalgesic effect in the grip force assay, the antinociceptive effect of a 5-min swim was not significantly different than that produced by a 15- or 30-min swim (Figure 1F). Antinociception was transient, returning to control values by 45 min after the termination of the swim (Figure 1E). The surface temperature of the tail before a 15-min swim was 26.8±0.2°C and decreased to 24.0±0.5°C after a cold swim. An identical increase in tail flick latency occurred in response to a warm swim (41°C) where the tail temperature increased (30.6±0.4°C) rather than decreased. Thus, thermal antinociception appeared to result from the stress of the swim rather than the water-induced change in temperature of the tail.

3.2. Swim-induced hyperalgesia is diminished by morphine

To determine whether the decrease in grip force induced by a forced swim is a reflection of pain or merely weakness, we investigated whether morphine (10 mg/kg i.p.), a potent antinociceptive opioid compound, was able to influence the decrease in grip force responses induced by a swim. We validated the antinociceptive effect of morphine by showing that tail flick latencies were increased following this dose of morphine (Figure 2B). Morphine had no effect on grip force responses in the absence of a swim, indicating that grip force responses cannot be increased above their maximum as reflected in their control values (Figure 2A). When injected 15 min prior to a cold swim, morphine attenuated the decrease in grip force induced immediately following the swim, confirming that this decrease reflects enhanced nociception rather than weakness.

Fig. 2.

Effect of morphine and of RTX on swim stress-induced decreases in grip force values. Grip force was measured before and after a 15-min swim in 26°C water. Morphine was delivered at a dose of 10 mg/kg i.p. 15 min prior to the onset of the swim (A) or before the tail flick assay (51°C) (B). Also in the lower panel, RTX was delivered at a dose of 0.125 µg i.t. 24 hr before testing in the tail flick assay (B). Statistical analyses on panel A were performed using a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis. Significant differences (P<0.05) between groups are indicated by an asterisk. In panel B, statistical analyses were performed using unpaired Student’s t-test where the asterisk indicates P<0.05 when compared to vehicle.

3.3. Effect of CRF1 and CRF2 receptor antagonists on hyperalgesia

To determine the possible role of CRF1 or 2 receptors located in the spinal cord area on swim stress-induced hyperalgesia, we pretreated mice with NBI-35965 (50 µg/5 µl i.t.), a CRF1 receptor antagonist, or astressin 2B (20 µg/5 µl i.t.), a CRF2 receptor antagonist, 15 min prior to the swim. The dose of NBI-35965 had no effect on grip force responses when given either in the presence or absence of a swim stress (Figure 3A). The activity of NBI-35965 used was validated by its ability to inhibit a 15-min swim stress-induced increase in corticosterone (Figure 3C), consistent with an inhibition of CRF1 receptors, but was small enough that it failed to inhibit urocortin I-induced decreases in body temperature (Figure 3D), an effect induced by activation of CRF2 receptors (Telegdy et al., 2006; Turek and Ryabinin, 2005). Astressin 2B significantly attenuated cold swim-induced hyperalgesia to a degree that did not differ from vehicle-injected controls, while having no effect on control animals who did not swim (Figure 3B). The efficacy of astressin 2B used was validated by its ability to completely inhibit urocortin I-induced decreases in body temperature (Figure 3D), while it failed to inhibit stress-induced increases in circulating corticosterone (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3.

Effect of antagonism of CRF1 and CRF2 sites on the cold stress-induced decrease in grip force. Panel A illustrates the effect of NBI-35965 (NBI), a CRF1 antagonist, on grip force, while panel B illustrates the effect of astressin 2B, a CRF2 receptor antagonist. Each drug was injected 15 min prior to the onset of a 15-min cold (26°C) swim. Panel C shows that the chosen dose of NBI-35965 (50 µg/5 µl i.c.v.) was physiologically active, as it was sufficient when injected 30 min prior to a swim stress to prevent the increase in plasma corticosterone, a CRF1 receptor-mediated effect. Similarly, in a separate experiment, 20 µg/5 µl of astressin 2B was injected i.t. and found to prevent the decrease in body temperature at 4 h after injection of 10 µg/5µl of urocortin I, a CRF2 receptor-mediated effect (D). Statistical analyses were performed in panels A and B using a two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Data in panels C and D were analyzed using an unpaired Students t-test (swim to no swim), and a one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis comparing data after the swim in panel C and all data in panel D. Significance (P<0.05) indicated by an asterisk.

3.4. Effect of TRPV1 receptor blockade on swim-induced hyperalgesia

To determine whether the swim-induced musculoskeletal hyperalgesia was mediated by TRPV1 receptor activity, we pretreated mice i.t. with a desensitizing dose of RTX (0.125 µg injected 6 days before the swim). Pretreatment with RTX i.t. failed to prevent the decrease in grip force induced by a cold swim when compared to mice similarly pretreated with vehicle (Figure 4A). The ability of this dose and route of RTX to desensitize TRPV1 receptors was validated by its ability to block capsaicin-induced (2 mg/kg s.c.) musculoskeletal hyperalgesia in preliminary studies. Furthermore, while a single central injection of this dose of RTX decreased grip force values 24 h later (Figure 4E), it prevented the hyperalgesic effect of a second i.t. injection of the same dose delivered 4 days later. This demonstrates that the dose of RTX used was capable of inducing desensitization. A similar desensitization is produced by this dose and route of RTX in the tail flick assay where it produced antinociception (Figure 2B). Because TRPV1 sites are located on warm thermosensitive primary afferent fibers, we reasoned that the stress induced by a cold swim may not be mediated by pathways that involve TRPV1 receptors whereas those on warm nociceptors may. We therefore examined the effect of RTS on a warm (41°C) swim to determine whether that requires TRPV1 activity either for the thermosensory input or for the transmission of musculoskeletal nociception resulting from the heat stress. We found that the stress of a warm swim transiently decreased grip force in mice (Figure 4C,D) in a fashion identical to the effect produced by a cold swim (Figure 4A,B). The magnitude of the decrease in grip force immediately after the warm swim was approximately the same as that after a cold swim and the duration of hyperalgesia was similarly short, returning to control values by 15 min after the termination of the swim. Pretreatment with RTX, at even a higher dose (0.25 µg i.t.) had no effect on the expression of musculoskeletal hyperalgesia following the warm swim (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Effect of desensitization and antagonism of TRPV1 receptors on grip force responses measured before and immediately after each swim. Mice were subjected to a 15-min swim in cold (26°C) (A) or in warm (41°C) water (C) after pretreatment with a desensitizing dose of RTX injected 6 days previously (0.125 µg) or 17 days previously (0.1 mg/kg s.c). Separate groups of mice were swum in cold (B) or warm water (D) 15 min after pretreatment with SB-366791 given either i.t. (30 µg/mouse) or i.c.v (30 µg/mouse), or 30 min after SB-366791 delivered i.p. (0.5 mg/kg). Statistical analyses were performed using a paired Student’s t-test comparing the effect of each drug to its vehicle-injected control group. The lower two panels (E,F) demonstrate the effect of the doses of RTX and of SB-366791 used in panels A and C in additional groups of mice. Compared to vehicle-injected control mice, a single injection of RTX (0.125 µg/mouse i.t.) decreased grip force values 24 hr later, but 4 days later the hyperalgesic effect of a second injection of this dose of RTX was absent in RTX-pretreated mice, but not in those pretreated with vehicle. This illustrates the development of desensitization to the hyperalgesic effect of RTX (E). SB-366791 (0.5 mg/kg i.p.) 20 min before an injection of capsaicin (2 mg/kg s.c.) prevented capsaicin-induced decreases in grip force values (F). Statistical analyses were performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis (E,F). Significant differences (P<0.05) are shown by the asterisk, as indicated. The number sign indicates P<0.05 when a group was different from all others.

RTX was then injected peripherally (0.1 mg/kg s.c.) 17 days prior to the forced swim. The ability of this dose and route of RTX to desensitize TRPV1 receptors was validated in preliminary studies by its ability to produce insensitivity of mice to the initial musculoskeletal hyperalgesic effect of capsaicin in the grip force assay and by its ability to produce a protracted thermal antinociception (1 to >30 days) measured using the tail flick assay (Figure 2B). In spite of this complete desensitization, grip force was still reduced immediately following the forced swim at either 26° or 41°C in both saline- and RTX-pretreated mice (Figure 4A,C).

The lack of TRPV1 receptor involvement in swim-induced hyperalgesia was also verified by the failure of SB-366791, a TRPV1 antagonist, to inhibit swim-induced hyperalgesia. Compared to vehicle-injected controls, SB-366791 had no effect on grip force responses and failed to attenuate the decrease in grip force induced by either the cold or warm swim (Figure 4B,D) when injected i.p. (0.5 mg/kg) 30 min before the swim, or either i.t. or i.c.v. (30 µg/mouse) 15 min before the swim. The dose and route of SB-366791 used (0.5 mg/kg i.p.) was validated by its ability to prevent a capsaicin-induced (2 mg/kg s.c.) decrease in grip force values (Figure 4F).

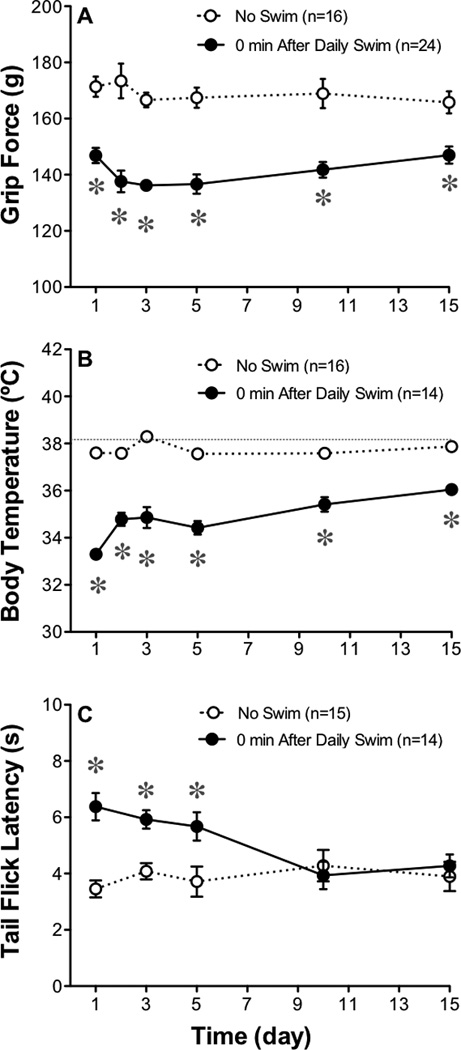

3.5. Effect of repeated daily swim on grip force responses, body temperature, and tail flick latency

When mice were subjected to a daily forced swim in cold (26°C) water, grip force responses were decreased at the end of the swim each day for two weeks (Figure 5A). The greatest decrease in grip force occurred between days 1 and 2, however, the decrease in grip force responses that were produced by the remaining 15 daily exposures to a cold swim did not differ in magnitude or duration (data not shown) from that induced by the first swim.

Fig. 5.

Effect of 15 daily swims on grip force responses, body temperature and tail flick latencies. The magnitude of the grip force responses taken immediately after a daily 15-min swim (26°C) were compared to values from groups not subjected to the daily swim (A). Each day, grip force responses returned to their pre-injection control values by 1 hr or less after the termination of each swim. Body temperature (B) and tail flick latencies (51°C) were also measured immediately after the 15-min swim (C). Statistical analyses of each panel were performed using a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis where the asterisk indicates P<0.05 when compared to vehicle-injected controls.

Rectal temperatures taken immediately after each of the 15 daily forced swims decreased to values below normal (Figure 5B), but returned to control values 15 min after the termination of each swim (Figure 1). The drop in body temperature was greatest on day one. In contrast to decreases in grip force and body temperature values following the cold swim, tolerance develops to the swim stress-induced thermal antinociception as tail flick responses returned to control values by day 10 (Figure 5C).

4. Discussion

Swim stress induces a transient musculoskeletal hyperalgesia in rats (Okamoto et al., 2012; Suarez-Roca et al., 2006a). The present study confirms the development of an identical hyperalgesia following daily swim stress in mice. Our study extends previous work in this area by showing that CRF2 receptors in the spinal cord area are important in the generation of this stress-induced musculoskeletal hyperalgesia, however, unlike other types of hyperalgesia, these signals are transmitted along spinal and primary afferent pathways that do not express TRPV1 receptors.

In our studies, a 15-min swim in cold (26°C) water caused hyperalgesia in mice when measured using the grip force assay, consistent with previous work in rats (Suarez-Roca et al., 2006a). Just as hyperalgesia in rats was validated by attenuation of the decrease in grip force by diclofenac and by morphine (Suarez-Roca et al., 2006a), we found that morphine attenuated the decrease in grip force in mice. The sensitivity to morphine supports the conclusion that stress-induced decreases in grip force measured in the present study resulted from nociception rather than weakness.

In addition to musculoskeletal hyperalgesia, we observed that swim stress induced a simultaneous antinociception in the tail flick assay consistent with previous studies of thermal nociception measured using either the tail flick (Grisel et al., 1993) or hot plate assays (Marek et al., 1993; Mogil et al., 1996; Vaccarino and Clavier, 1997). Each modality of pain is influenced differently by stress allowing stress to induce a decrease in thermal nociception (antinociception) in the same mice as those in which decreases in grip force (musculoskeletal hyperalgesia) were observed. In previous studies of stress-induced hyperalgesia, differential modulation of muscle and cutaneous thermal nociceptive pathways was suggested by the finding that milnacipran decreased swim-induced muscle hyperalgesia (grip strength) without affecting cutaneous thermal hyperalgesia (hot plate) in rats (Suarez-Roca et al., 2006a).

CRF and urocortin I are not only readily found throughout the spinal cord (Korosi et al., 2007), CRF analogs are clearly able to alter nociceptive signals (Imbe et al., 2010; Lariviere and Melzack, 2000). However, it was unclear whether they are released endogenously and involved in the spinal modulation of musculoskeletal nociception following stress. We addressed this question using the CRF receptor antagonists NBI-35965, a CRF1-selective compound, and astressin 2B, a CRF2-selective compound, to determine the contribution of these receptors to swim stress-induced hyperalgesia. Based on the ability of astressin 2B, but not NBI-35965, to attenuate the decrease in grip force responses after the swim stress, CRF2 receptor activity appears to contribute to stress-induced musculoskeletal hyperalgesia. This is consistent with the CRF2 receptor mediation of hypersensitivity of the urinary bladder induced by footshock in the rat (Robbins and Ness, 2008). Which CRF analog is released endogenously to produce this hyperalgesic effect cannot be determined from these studies. Although urocortin I binds more readily with CRF2 receptors than CRF, making urocortins good candidates, CRF is found more abundantly in the normal healthy spinal cord than urocortin I (Korosi et al., 2007) providing a concentration of CRF that may be sufficient to activate CRF2 sites.

TRPV1 receptors are distributed throughout the body, including the brain, spinal cord (Kim et al., 2012) and peripheral nervous system (Menigoz and Boudes, 2011; Roberts et al., 2004; Szallasi et al., 1995) where they play a vital role in hyperalgesia. Because TRPV1 ligands are crucial to the enhancement of nociception in many models of hyperalgesia (Chung et al., 2011; Fujii et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 2011; Szabo et al., 2005), we questioned whether TRPV1 receptor-expressing neuronal populations mediate stress-induced musculoskeletal hyperalgesia. In our study, RTX delivered either intrathecally or subcutaneously, induced thermal antinociception, consistent with an efficacious dose, but failed to prevent the decrease in grip force induced by a swim stress. Delivered subcutaneously, RTX desensitizes TRPV1 sites on primary afferent C-fibers while intrathecal injections desensitize TRPV1 sites on interneurons (Kim et al., 2012) or postsynaptic neurons in the dorsal horn (Gibson et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2009). In addition to RTX, SB-366791, a TRPV1 receptor antagonist, injected i.p., i.t., or i.c.v had no effect on swim-induced decreases in grip force responses, in spite of its ability to inhibit the effect of capsaicin. The combined results from RTX-induced desensitization and TRPV1 receptor antagonism indicate that neither central nor peripheral afferent neurons that express TRPV1 receptors are necessary for swim stress-induced hyperalgesia in normal healthy mice. This is consistent with the conclusion that pretreatment with TRPV1 antagonists or RTX (to desensitize TRPV1 sites) have no effect on acute models of mechanical hyperalgesia but attenuate mechanical hyperalgesia (measured using von Frey fibers or Randall-Selitto assays) when induced by models of nerve injury or inflammation (Bishnoi et al., 2011b; Kanai et al., 2007; Tender et al., 2008; Watabiki et al., 2011a; Watabiki et al., 2011b).

No tolerance to the musculoskeletal hyperalgesic effect of stress appears to develop when presented daily based on the persistence of the hyperalgesic response following 15 daily forced swims. This is consistent with similar findings that swim stress-induced hyperalgesia can be elicited daily when measured using chemical sensitivity (formalin assay: (Imbe et al., 2010; Quintero et al., 2011; Quintero et al., 2003; Suarez-Roca et al., 2008)). Stress-induced hyperalgesia in rodents induced by repeated exposure to alternating episodes of cold and warm also lasts for several days with no apparent adaptation when measured using the tail flick (Hata et al., 1988; Kita et al., 1979), tail pressure (Hata et al., 1988; Kita et al., 1979), paw pressure (Satoh et al., 1992), acetic acid or phenylquinone assays (Kita et al., 1979). In contrast, when acute stress-induced thermal antinociception is monitored chronically (Grisel et al., 1993; Marek et al., 1993; Mogil et al., 1996; Vaccarino and Clavier, 1997) tolerance develops to antinociception (Imbe et al., 2010). We too demonstrated in the tail flick assay that tolerance develops to the swim stress-induced thermal antinociception during repeated daily exposure to the stress as it is resolved by day 10. Chronic exposure to a stress can even eventually lead to hyperalgesia rather than antinociception along thermal pathways (Quintero et al., 2000; Suarez-Roca et al., 2006a; Suaudeau and Costentin, 2000), perhaps by unmasking a more persistent hyperalgesic component.

5. Conclusions

Our data illustrate that musculoskeletal hyperalgesia, measured using the grip force assay, can be induced daily in mice by the stress of a cold forced swim. The resulting hyperalgesia is mediated, in part, by spinal CRF2 receptors and transmitted along spinal nociceptive pathways that do not require TRPV1 receptor activity.

Highlights.

-

○

Forced swims cause morphine-sensitive decreases in grip force responses in mice.

-

○

A CRF2 receptor antagonist attenuates hyperalgesia.

-

○

Desensitizing or antagonizing TRPV1 receptors fails to prevent stress-induced hyperalgesia.

-

○

Swim-induced musculoskeletal hyperalgesia is mediated by CRF2, not TRPV1 receptors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from NIH from the National Institutes on Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases [AR056092].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bishnoi M, Bosgraaf CA, Abooj M, Zhong L, Premkumar LS. Streptozotocin-induced early thermal hyperalgesia is independent of glycemic state of rats: role of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1(TRPV1) and inflammatory mediators. Mol Pain. 2011a;7:52. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishnoi M, Bosgraaf CA, Premkumar LS. Preservation of acute pain and efferent functions following intrathecal resiniferatoxin-induced analgesia in rats. J Pain. 2011b;12:991–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh DJ, Lee H, Lo L, Shields SD, Zylka MJ, Basbaum AI, Anderson DJ. Distinct subsets of unmyelinated primary sensory fibers mediate behavioral responses to noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9075–9080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MK, Jung SJ, Oh SB. Role of TRP channels in pain sensation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:615–636. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churyukanov M, Legrain V, Mouraux A. Thermal detection thresholds of Adelta- and C-fibre afferents activated by brief CO2 laser pulses applied onto the human hairy skin. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coste SC, Murray SE, Stenzel-Poore MP. Animal models of CRH excess and CRH receptor deficiency display altered adaptations to stress. Peptides. 2001;22:733–741. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas-Szallasi T, Bennett GJ, Blumberg PM, Hokfelt T, Lundberg JM, Szallasi A. Vanilloid receptor loss is independent of the messenger plasticity that follows systemic resiniferatoxin administration. Brain Res. 1996;719:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete EM, Zorrilla EP. Physiology, pharmacology, and therapeutic relevance of urocortins in mammals: ancient CRF paralogs. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2007;28:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes ES, Russell FA, Spina D, McDougall JJ, Graepel R, Gentry C, Staniland AA, Mountford DM, Keeble JE, Malcangio M, Bevan S, Brain SD. A distinct role for transient receptor potential ankyrin 1, in addition to transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, in tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced inflammatory hyperalgesia and Freund's complete adjuvant-induced monarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:819–829. doi: 10.1002/art.30150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Y, Ozaki N, Taguchi T, Mizumura K, Furukawa K, Sugiura Y. TRP channels and ASICs mediate mechanical hyperalgesia in models of inflammatory muscle pain and delayed onset muscle soreness. Pain. 2008;140:292–304. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson HE, Edwards JG, Page RS, Van Hook MJ, Kauer JA. TRPV1 channels mediate long-term depression at synapses on hippocampal interneurons. Neuron. 2008;57:746–759. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goso C, Piovacari G, Szallasi A. Resiniferatoxin-induced loss of vanilloid receptors is reversible in the urinary bladder but not in the spinal cord of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1993;162:197–200. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90594-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisel JE, Fleshner M, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Opioid and nonopioid interactions in two forms of stress-induced analgesia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;45:161–172. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata T, Kita T, Itoh E, Kawabata A. The relationship of hyperalgesia in SART (repeated cold)-stressed animals to the autonomic nervous system. J Auton Pharmacol. 1988;8:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1988.tb00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoheisel U, Reinohl J, Unger T, Mense S. Acidic pH and capsaicin activate mechanosensitive group IV muscle receptors in the rat. Pain. 2004;110:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P. Local effector functions of capsaicin-sensitive sensory nerve endings: involvement of tachykinins, calcitonin gene-related peptide and other neuropeptides. Neuroscience. 1988;24:739–768. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylden JL, Wilcox GL. Intrathecal morphine in mice: a new technique. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;67:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadarola MJ, Mannes AJ. The vanilloid agonist resiniferatoxin for interventional-based pain control. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:2171–2179. doi: 10.2174/156802611796904942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbe H, Iwai-Liao Y, Senba E. Stress-induced hyperalgesia: animal models and putative mechanisms. Front Biosci. 2006;11:2179–2192. doi: 10.2741/1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbe H, Okamoto K, Donishi T, Senba E, Kimura A. Involvement of descending facilitation from the rostral ventromedial medulla in the enhancement of formalin-evoked nocifensive behavior following repeated forced swim stress. Brain Res. 2010;1329:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorum E. Noradrenergic mechanisms in mediation of stress-induced hyperalgesia in rats. Pain. 1988;32:349–355. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y, Hara T, Imai A, Sakakibara A. Differential involvement of TRPV1 receptors at the central and peripheral nerves in CFA-induced mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2007;59:733–738. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.5.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehl LJ, Hamamoto DT, Wacnik PW, Croft DL, Norsted BD, Wilcox GL, Simone DA. A cannabinoid agonist differentially attenuates deep tissue hyperalgesia in animal models of cancer and inflammatory muscle pain. Pain. 2003;103:175–186. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehl LJ, Trempe TM, Hargreaves KM. A new animal model for assessing mechanisms and management of muscle hyperalgesia. Pain. 2000;85:333–343. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Back SK, Davies AJ, Jeong H, Jo HJ, Chung G, Na HS, Bae YC, Kim SJ, Kim JS, Jung SJ, Oh SB. TRPV1 in GABAergic interneurons mediates neuropathic mechanical allodynia and disinhibition of the nociceptive circuitry in the spinal cord. Neuron. 2012;74:640–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissin I, Szallasi A. Therapeutic Targeting of TRPV1 by Resiniferatoxin, from Preclinical Studies to Clinical Trials. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011 doi: 10.2174/156802611796904924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita T, Hata T, Iida J, Yoneda R, Isida S. Decrease in pain threshold in SART stressed mice. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1979;29:479–482. doi: 10.1254/jjp.29.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korosi A, Kozicz T, Richter J, Veening JG, Olivier B, Roubos EW. Corticotropin-releasing factor, urocortin 1, and their receptors in the mouse spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502:973–989. doi: 10.1002/cne.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs KJ, Papic JC, Larson AA. Movement-evoked hyperalgesia induced by lipopolysaccharides is not suppressed by glucocorticoids. Pain. 2008;136:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lariviere WR, Melzack R. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in pain and analgesia. Pain. 2000;84:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light AR, Hughen RW, Zhang J, Rainier J, Liu Z, Lee J. Dorsal root ganglion neurons innervating skeletal muscle respond to physiological combinations of protons, ATP, and lactate mediated by ASIC, P2X, and TRPV1. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1184–1201. doi: 10.1152/jn.01344.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovick TA. Pro-nociceptive action of cholecystokinin in the periaqueductal grey: a role in neuropathic and anxiety-induced hyperalgesic states. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:852–862. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek P, Mogil JS, Belknap JK, Sadowski B, Liebeskind JC. Levorphanol and swim stress-induced analgesia in selectively bred mice: evidence for genetic commonalities. Brain Res. 1993;608:353–357. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91479-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V, Wang L, Rivier J, Grigoriadis D, Tache Y. Central CRF, urocortins and stress increase colonic transit via CRF1 receptors while activation of CRF2 receptors delays gastric transit in mice. J Physiol. 2004;556:221–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menigoz A, Boudes M. The Expression Pattern of TRPV1 in Brain. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13025–13027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2589-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mense S. Peripheral Mechaniism of Muscle Nociception and Local Muscle Pain. J Musculoskelet Pain. 1992;1:133–170. [Google Scholar]

- Mogil JS, Sternberg WF, Balian H, Liebeskind JC, Sadowski B. Opioid and nonopioid swim stress-induced analgesia: a parametric analysis in mice. Physiol Behav. 1996;59:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor PJ, Cook DB. Exercise and pain: the neurobiology, measurement, and laboratory study of pain in relation to exercise in humans. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1999;27:119–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Tashiro A, Chang Z, Thompson R, Bereiter DA. Temporomandibular joint-evoked responses by spinomedullary neurons and masseter muscle are enhanced after repeated psychophysical stress. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;36:2025–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD. Animal model of depression. Biomedicine. 1979;30:139–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Blavet N, Deniel M, Jalfre M. Immobility induced by forced swimming in rats: effects of agents which modify central catecholamine and serotonin activity. Eur J Pharmacol. 1979;57:201–210. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(79)90366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Jalfre M. Behavioral despair in mice: a primary screening test for antidepressants. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1977;229:327–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero L, Cardenas R, Suarez-Roca H. Stress-induced hyperalgesia is associated with a reduced and delayed GABA inhibitory control that enhances post-synaptic NMDA receptor activation in the spinal cord. Pain. 2011;152:1909–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero L, Cuesta MC, Silva JA, Arcaya JL, Pinerua-Suhaibar L, Maixner W, Suarez-Roca H. Repeated swim stress increases pain-induced expression of c-Fos in the rat lumbar cord. Brain Res. 2003;965:259–268. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero L, Moreno M, Avila C, Arcaya J, Maixner W, Suarez-Roca H. Long-lasting delayed hyperalgesia after subchronic swim stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:449–458. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JM, Holsboer F. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors 1 and 2 in anxiety and depression. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(01)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MT, Ness TJ. Footshock-induced urinary bladder hypersensitivity: role of spinal corticotropin-releasing factor receptors. J Pain. 2008;9:991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JC, Davis JB, Benham CD. [3H]Resiniferatoxin autoradiography in the CNS of wild-type and TRPV1 null mice defines TRPV1 (VR-1) protein distribution. Brain Res. 2004;995:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts K, Shenoy R, Anand P. A novel human volunteer pain model using contact heat evoked potentials (CHEP) following topical skin application of transient receptor potential agonists capsaicin, menthol and cinnamaldehyde. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:926–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh M, Kuraishi Y, Kawamura M. Effects of intrathecal antibodies to substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide and galanin on repeated cold stress-induced hyperalgesia: comparison with carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia. Pain. 1992;49:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90151-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Roca H, Leal L, Silva JA, Pinerua-Shuhaibar L, Quintero L. Reduced GABA neurotransmission underlies hyperalgesia induced by repeated forced swimming stress. Behav Brain Res. 2008;189:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Roca H, Quintero L, Arcaya JL, Maixner W, Rao SG. Stress-induced muscle and cutaneous hyperalgesia: differential effect of milnacipran. Physiol Behav. 2006a;88:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Roca H, Silva JA, Arcaya JL, Quintero L, Maixner W, Pinerua-Shuhaibar L. Role of mu-opioid and NMDA receptors in the development and maintenance of repeated swim stress-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Behav Brain Res. 2006b;167:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suaudeau C, Costentin J. Long lasting increase in nociceptive threshold induced in mice by forced swimming: involvement of an endorphinergic mechanism. Stress. 2000;3:221–227. doi: 10.3109/10253890009001126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A, Helyes Z, Sandor K, Bite A, Pinter E, Nemeth J, Banvolgyi A, Bolcskei K, Elekes K, Szolcsanyi J. Role of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptors in adjuvant-induced chronic arthritis: in vivo study using gene-deficient mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:111–119. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid receptor loss in rat sensory ganglia associated with long term desensitization to resiniferatoxin. Neurosci Lett. 1992;140:51–54. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90679-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Cortright DN, Blum CA, Eid SR. The vanilloid receptor TRPV1: 10 years from channel cloning to antagonist proof-of-concept. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:357–372. doi: 10.1038/nrd2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Joo F, Blumberg PM. Duration of desensitization and ultrastructural changes in dorsal root ganglia in rats treated with resiniferatoxin, an ultrapotent capsaicin analog. Brain Res. 1989;503:68–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91705-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Nilsson S, Farkas-Szallasi T, Blumberg PM, Hokfelt T, Lundberg JM. Vanilloid (capsaicin) receptors in the rat: distribution in the brain, regional differences in the spinal cord, axonal transport to the periphery, and depletion by systemic vanilloid treatment. Brain Res. 1995;703:175–183. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telegdy G, Adamik A, Toth G. The action of urocortins on body temperature in rats. Peptides. 2006;27:2289–2294. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tender GC, Li YY, Cui JG. Vanilloid receptor 1-positive neurons mediate thermal hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia. Spine J. 2008;8:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek VF, Ryabinin AE. Ethanol versus lipopolysaccharide-induced hypothermia: involvement of urocortin. Neuroscience. 2005;133:1021–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino AL, Clavier MC. Blockade of tolerance to stress-induced analgesia by MK-801 in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;56:435–439. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00235-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga A, Nemeth J, Szabo A, McDougall JJ, Zhang C, Elekes K, Pinter E, Szolcsanyi J, Helyes Z. Effects of the novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist SB366791 in vitro and in vivo in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2005;385:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal C, Jacob J. Hyperalgesia induced by emotional stress in the rat: an experimental animal model of human anxiogenic hyperalgesia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;467:73–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb14619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabiki T, Kiso T, Kuramochi T, Yonezawa K, Tsuji N, Kohara A, Kakimoto S, Aoki T, Matsuoka N. Amelioration of neuropathic pain by novel transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 antagonist AS1928370 in rats without hyperthermic effect. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011a;336:743–750. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabiki T, Kiso T, Tsukamoto M, Aoki T, Matsuoka N. Intrathecal administration of AS1928370, a transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 antagonist, attenuates mechanical allodynia in a mouse model of neuropathic pain. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011b;34:1105–1108. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoven HA, de Vet HC, Picavet HS. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders is systematically higher in women than in men. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:717–724. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210912.95664.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HY, Chen SR, Chen H, Pan HL. The glutamatergic nature of TRPV1-expressing neurons in the spinal dorsal horn. J Neurochem. 2009;108:305–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]