Abstract

Cellular transitions are important for all life. Such transitions, including cell fate decisions, often employ positive feedback regulation to establish and stabilize new cellular states. However, positive feedback is unlikely to underlie stable cell cycle arrest in yeast exposed to mating pheromone because the signaling pathway is linear, rather than bistable, over a broad range of extracellular pheromone concentration. We show that the stability of the pheromone arrested state results from coherent feed-forward regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor Far1. This network motif is effectively isolated from the more complex regulatory network in which it is embedded. Fast regulation of Far1 by phosphorylation allows rapid cell cycle arrest and reentry, whereas slow Far1 synthesis reinforces arrest. We thus expect coherent feed-forward regulation to be frequently implemented at reversible cellular transitions because this network motif can achieve the ostensibly conflicting aims of arrest stability and rapid reversibility without loss of signaling information.

INTRODUCTION

A genome encodes several cellular states (or fates) distinguished by morphology or gene expression. Cells transition from one state to another in response to changing input signals that are processed by specific regulatory networks. Successful cellular transitions require that cells first commit to, and then maintain, a new cellular state. Notably, commitment has to be accurate even in the presence of environmental fluctuations as well as stochastic noise due to low numbers of key regulatory molecules (Balazsi et al., 2011; Di Talia et al., 2007; Johnston and Desplan, 2010). Following commitment, cells must reliably and consistently activate a state-specific gene expression program because co-expression of exclusive programs can have fatal results (Doncic et al., 2011).

Despite these shared features for all cellular transitions, we expect distinct context-dependent physiological requirements to be reflected in the associated regulatory networks. Cellular transitions may be divided into two classes: reversible and irreversible. Molecular networks regulating irreversible transitions often employ strong positive feedback loops to ensure the stability of downstream cellular states (Jukam and Desplan, 2010). One such example of an irreversible transition is the process of Xenopus oocyte maturation, which can be initiated by a transient stimulus (Xiong and Ferrell, 2003). Once activated, the positive feedback loop, comprised exclusively of individually reversible chemical reactions, maintains its activity in the absence of extracellular stimulus. Increased stability of the matured state arises specifically due irreversible positive feedback. However, this route to stability poses a problem for transitions requiring reversibility, such as cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage or defects in spindle assembly. Here, the twin aims of stability and reversibility appear to conflict. To determine signaling principles governing such reversible cellular states, we decided to examine pheromone arrest in budding yeast.

Upon exposure to mating pheromone (α-factor), haploid yeast cells arrest the cell cycle in early G1 phase and prepare to mate (Hartwell et al., 1974). Successful mating requires a stable cell cycle arrest to allow for altered gene expression, chemotropism, and cell fusion (Madhani, 2007). However, cells reenter the cell cycle if the extracellular pheromone is removed as in the case where a competitor mates with the prospective partner. Thus, both stability and reversibility are required of the regulatory system governing pheromone arrest.

The conflict between cell fusion (mating) and fission (cell cycle) is reflected in mutual inhibition at the interface between the mating and the cell cycle signaling pathways in budding yeast (Fig. 1A). To select the mitotic fate, the upstream G1 cyclin Cln3 activates the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) to phosphorylate the transcriptional inhibitor Whi5. This initiates a positive feedback loop centered on the downstream G1 cyclins Cln1 and Cln2 that drives entry to the cell cycle, and activates the downstream B-type cyclins (Costanzo et al., 2004; de Bruin et al., 2004; Skotheim et al., 2008). Importantly, this G1 control network exhibits a hysteretic response, i.e., that outputs such as CLN2 transcription depend on the history in the input G1 cyclin activity signal (Charvin et al., 2010). Once activated, the positive feedback loop is irreversible and will maintain its activity despite removal of the upstream activating G1 cyclin signal. Thus, G1 control is performed by a bistable system, in which a low- and a high-CDK activity state are separated by a well-defined commitment point (Doncic et al., 2011). Upon commitment to cell division, the G1 cyclins target the CDK-inhibitor Far1 for degradation (Gartner et al., 1998; Henchoz et al., 1997; McKinney et al., 1993) and inactivate the mating pathway scaffold protein Ste5 (Garrenton et al., 2009; Strickfaden et al., 2007). Conversely, mating arrest is effected by Far1, likely via stoichiometric inhibition of the G1 cyclin CDK complexes. Upon pheromone stimulation, Far1 is feed-forward regulated by the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) Fus3 (Gartner et al., 1998; Henchoz et al., 1997; Peter et al., 1993; Tyers and Futcher, 1993). Thus, a single input activates Far1 via two distinct mechanisms: Fus3 directly phosphorylates and activates Far1, and indirectly induces Far1 expression through the transcription factor Ste12 (Oehlen et al., 1996).

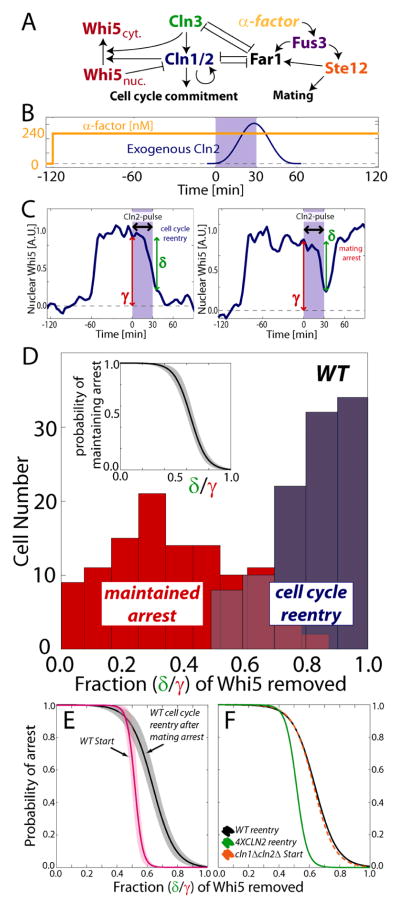

Figure 1.

The CDK-threshold for cell cycle entry is higher for pheromone arrested than freely cycling cells. (A) Regulatory schematic. (B) Experiment schematic for measuring cell cycle reentry threshold in arrested cells expressing an exogenous Cln2 pulse from an integrated MET3 promoter. (C) For each cell, we monitor its eventual cell fate (maintain arrest or reenter cell cycle) and measure the amount of Whi5-GFP removed from the nucleus by the exogenous Cln2 pulse (δ/γ). (D) Cell cycle reentry probability (inset) as a function of δ/γ and the corresponding histograms for cells maintaining arrest (red) or reentering the cell cycle (blue). (E) The amount of Whi5 export required for Start, the point of commitment to cell division for a freely cycling cell exposed to a step-increase in pheromone (magenta; see text for details) and the reentry threshold from panel D (black). Shaded areas denote 95% confidence intervals. (F) The thresholds for cell cycle reentry in WT cells (black) and cells with additional CLN2 alleles (4xCLN2; green), and Start in freely cycling cln1Δcln2Δ cells (orange).

The network structure that activates Far1 is called a coherent feed-forward loop, and many of its theoretical properties have been elucidated (Alon, 2007; Mangan and Alon, 2003). However, network motifs always exist within the context of more complex regulatory networks (Yeger-Lotem et al., 2004), suggesting that a simplified analysis of network motifs in isolation may be of limited value. For example, as described above, the coherent feed-forward regulation of Far1 by Fus3 is intertwined with the core cell cycle pathway at multiple points including the mutual inhibition of Far1 and the G1 cyclins as well as the inhibition of Ste5 by the G1 cyclins. In this context, it remains an open question if the analysis of a simple network motif, such as the coherent feed-forward regulation of Far1, can provide insight into the regulation of a potentially more complex cell fate decision such as the mating-mitosis switch.

While much was known about the pheromone-activated MAPK pathway, it was unclear if pheromone arrest is stabilized over time. We show here that the arrest is indeed stabilized. However, this stabilization of the pheromone arrested state is unlikely the result of positive feedback-driven hysteresis for two reasons. First, MAPK pathway activity, as measured by Fus3 phosphorylation or Ste12-dependent transcription, is linear over a broad range of extracellular pheromone concentration (Colman-Lerner et al., 2005; Paliwal et al., 2007; Takahashi and Pryciak, 2008; Yu et al., 2008). Second, we show that pheromone pathway activity is rapidly reversible upon a sharp decrease in the extra-cellular pheromone concentration. Here, we show that the stability of pheromone arrest results from transcriptional branch of the coherent feed-forward regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor Far1, and that this network motif can be considered in isolation of the network in which it is embedded due to the stability of Far1 during pheromone arrest. The implementation of feed-forward, rather than feedback, regulation allows arrest stability without affecting MAPK signaling pathway output. Maintaining a consistent and graded input-output relationship between pheromone and MAPK activity allows the cell to accurately measure the extracellular pheromone concentration while being reversibly arrested. Thus, we expect feed-forward regulation to be a key feature of the regulatory networks controlling reversible cellular transitions in a wide variety of contexts.

RESULTS

Pheromone arrest is reinforced

Since cell fusion requires an extended cell cycle arrest, we hypothesized that pheromone induced arrest is reinforced over time. In this context, reinforcement implies that it is more difficult for arrested cells to reenter the cell cycle than for cycling cells. Since cell cycle entry is driven by CDK activity, the reinforcement model predicts that the CDK activity threshold for cell cycle entry in pheromone-arrested cells should be higher than the corresponding threshold for cycling cells.

To determine the CDK thresholds, we required a CDK activity sensor and therefore examined cells expressing the G1 cyclin-CDK target WHI5 fused to green fluorescent protein (Costanzo et al., 2004). The nuclear concentration of Whi5-GFP likely reflects G1 cyclin activity because Whi5 nuclear export is promoted by CDK phosphorylation (Kosugi et al., 2009; Taberner et al., 2009). We previously found that the dynamic range of nuclear Whi5 ideal for the analysis of G1 cell cycle kinetics (Doncic et al., 2011; Skotheim et al., 2008), suggesting that Whi5 phosphorylation is rate limiting for G1 progression (Costanzo et al., 2004; de Bruin et al., 2004).

We previously employed Whi5-GFP to determine the CDK threshold for entering the mitotic cell cycle for freely cycling cells (Doncic et al., 2011). Briefly, asynchronously growing cells were exposed to a step-increase in pheromone (0 to 240nM α-factor). This allowed us to classify cells based on Hartwell’s original operational definition of Start as the point of commitment to the cell cycle. Pre-Start cells at the time of pheromone addition fail to exit G1 and arrest, while post-Start cells complete an additional mitotic cell cycle before arresting (Hartwell et al., 1974). For yeast exposed to a step-increase in pheromone concentration, Start, the point of commitment to division in freely cycling cells, corresponded to having exported 52±3% of the nuclear Whi5 (Doncic et al., 2011).

To determine the CDK activity threshold for cell cycle re-entry from the pheromone-arrested state we first arrested cells using 240nM α-factor. Arrested cells are characterized by low CDK activity and a large amount of nuclear Whi5-GFP. Next, the arrested cells were forced to express a pulse of exogenous Cln2 from an integrated methionine-regulated promoter (Charvin et al., 2008), MET3pr-CLN2, which resulted in some of the cells reentering the cell cycle and dividing (note that we refer to these cells as WT in the remainder of the text even though these cells contain genomic MET3pr-CLN2). We measured the amount of nuclear Whi5-GFP exported in response to the pulse of exogenous Cln2 and the eventual cell fate (Fig. 1B,C,D). 64±4% of nuclear Whi5 had to be removed for cell cycle reentry from mating arrest, compared with 52±3% for a cycling cell to progress through Start (p<10−4; Fig. 1E). The increased difficulty of reentering the mitotic cell cycle after exposure to mating pheromone supports the model that pheromone arrest is reinforced.

We next focused on finding the molecular basis of arrest reinforcement. The positive feedback loop that activates transcription of the G1 cyclins Cln1 and Cln2 is an important determinant of commitment in freely cycling cells. We thus decided to examine cell cycle reentry from the pheromone arrested state in cells lacking these cyclins (cln1Δcln2Δ). The cell cycle entry thresholds from arrest were similar in WT and cln1Δcln2Δ cells (p=0.36) suggesting complete inhibition of endogenous CLN1 and CLN2 during pheromone arrest. Consistent with the hypothesis that arrest reinforcement is similar to a loss of Cln1 and Cln2, the cell cycle entry thresholds for pheromone-arrested wild-type cells and freely cycling cln1Δcln2Δ cells were also indistinguishable (P=0.74; Fig. 1F). Next, we examined the threshold for cell cycle reentry in cells lacking the G1 cyclin Cln3 (cln3Δ), cells over-expressing CLN2 (4XCLN2) or FAR1 (3XFAR1), as well as cells containing FAR1 and STE5 alleles that cannot be inhibited by G1 cyclins (FAR1-S87A and STE5-8A). The results are shown in Fig.S1 and in Table S1. Only cells containing 3 additional copies of CLN2 (4XCLN2) entered the cell cycle from pheromone arrest at a lower threshold than WT cells (p<10−4; Fig. 1F). Taken together, these results suggest that mating arrest is reinforced primarily through increased inhibition of Cln1 and Cln2.

Cln1,2-dependent hysteresis in response to pheromone

The larger CDK threshold to reenter the cell cycle compared with freely cycling cells suggests that pheromone arrest is reinforced over time. If so, cells that have been arrested longer or previously exposed to higher pheromone concentrations should be more reluctant to enter the cell cycle. In other words, the reinforced arrest model predicts that cells should exhibit hysteresis in response to pheromone concentration. To test if arrest duration depends on the history of exposure to mating pheromone (Moore, 1984), i.e., exhibits hysteresis, we monitored cell cycle reentry times after exposing cells to a brief (30 min) pulse of high pheromone concentration (240nM), followed by a variety of lower pheromone concentrations (Fig. 2A). Cells pre-exposed to the high concentration pulse took much longer (often more than 1 hour) to reenter the cell cycle than naïve control cells exposed to the same final pheromone concentrations, but not exposed to the high pheromone pulse. This result demonstrates hysteresis and strongly supports the reinforced arrest model (Fig. 2B, S2 and S3).

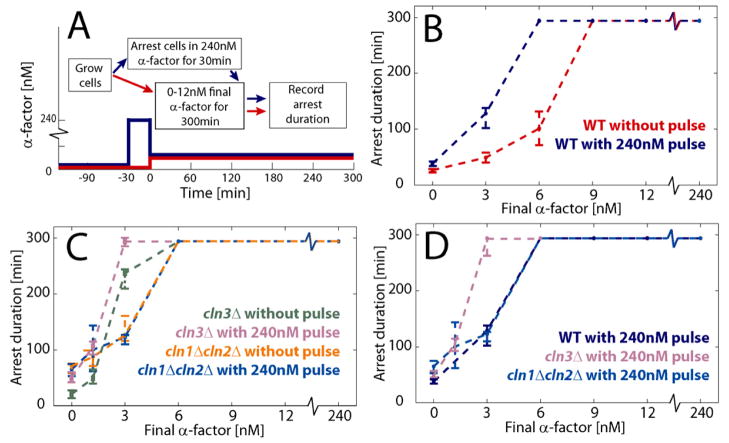

Figure 2.

Hysteresis in cell cycle kinetics in response to changes in pheromone concentration. (A) Experiment schematic (see methods). (B) Duration of arrest in daughter cells exposed to a 30 minute pulse of high pheromone concentration or control cells. (C) Hysteresis experiment for cells lacking Cln1,2 and Cln3. (D) Arrest duration for cells experiencing a pheromone pulse lacking either Cln3, or Cln1 and Cln2. Medians plotted with 95% confidence intervals computed using 10000 bootstrapping iterations.

Our genetic analysis of the cell cycle reentry threshold suggested that hysteresis results from increased inhibition of Cln1 and Cln2 in pheromone arrested cells, which might be due to increased transcription of the CDK inhibitor FAR1 (Chang and Herskowitz, 1990; Oehlen et al., 1996). Consistent with the hypothesis that increased Far1-dependent inhibition of CDK underlies reinforcement, cln1Δcln2Δ and far1Δcln1Δcln2Δ cells did not exhibit hysteresis (Fig. 2C, S2 and S3). Moreover, these results strongly support our cell cycle entry threshold measurements shown in Figure 1 in two ways: First, cell cycle kinetics in WT cells experiencing a high pheromone pulse is similar to the kinetics of cln1Δcln2Δ cells not receiving the pulse; Second, cell cycle kinetics of WT and cln1Δcln2Δ cells receiving a high pheromone pulse was also similar (Fig. 2C,D and S2D,G–J). Given an increased inhibition of Cln1 and Cln2 compared with Cln3, the latter would remain the primary activator of reentry for arrested cells. If true, we would expect cells lacking CLN3 (cln3Δ) to reenter the cell cycle from pheromone arrest much slower than WT cells while still being hysteretic. Indeed, this was found to be the case (Fig. 2C,D, S2C,D and S3E,F). Thus, the pheromone-arrested state is likely stabilized through increased Far1-dependent inhibition of Cln1 and Cln2 so that Cln3 is the primary driver of cell cycle reentry.

MAPK pathway activity is rapidly reversible

An alternative explanation for arrest reinforcement is that MAPK activity reverses slowly upon a decrease in the extracellular pheromone concentration. To test this alternative hypothesis, we examined pathway activity in a strain expressing a STE5-YFP fusion protein from the endogenous locus (Yu et al., 2008). During exposure to mating pheromone, the Ste5-YFP scaffold reversibly localizes to the membrane at the shmoo tip to mediate pheromone signaling (Garrenton et al., 2009). Since membrane localization of Ste5 is required for pheromone signaling, Ste5-localization allows us to asses MAPK activity in single cells (Bush and Colman-Lerner, 2013; Strickfaden et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2008). To examine the kinetics of signaling reversibility, we grew cells in 240nM pheromone for 2 hours and then acutely removed all pheromone. In most cells Ste5-YFP was dissociated from the membrane within 3 minutes, which implies that MAPK activity is rapidly reversible (Fig. 3A,B and S4). To confirm this, we also examined cells expressing GFP from an integrated FUS1 promoter (FUS1pr-GFP), a commonly used reporter of pheromone-induced gene expression. Consistent with rapid reversibility, we observed that the pheromone-induced transcription rate decreased in most cells within 10 minutes of a drop in pheromone concentration, which is on the same time scale as GFP maturation kinetics (Fig. 3C,3D). Taken together, these results imply that MAPK activity is rapidly reversible after a decrease in the extracellular pheromone concentration.

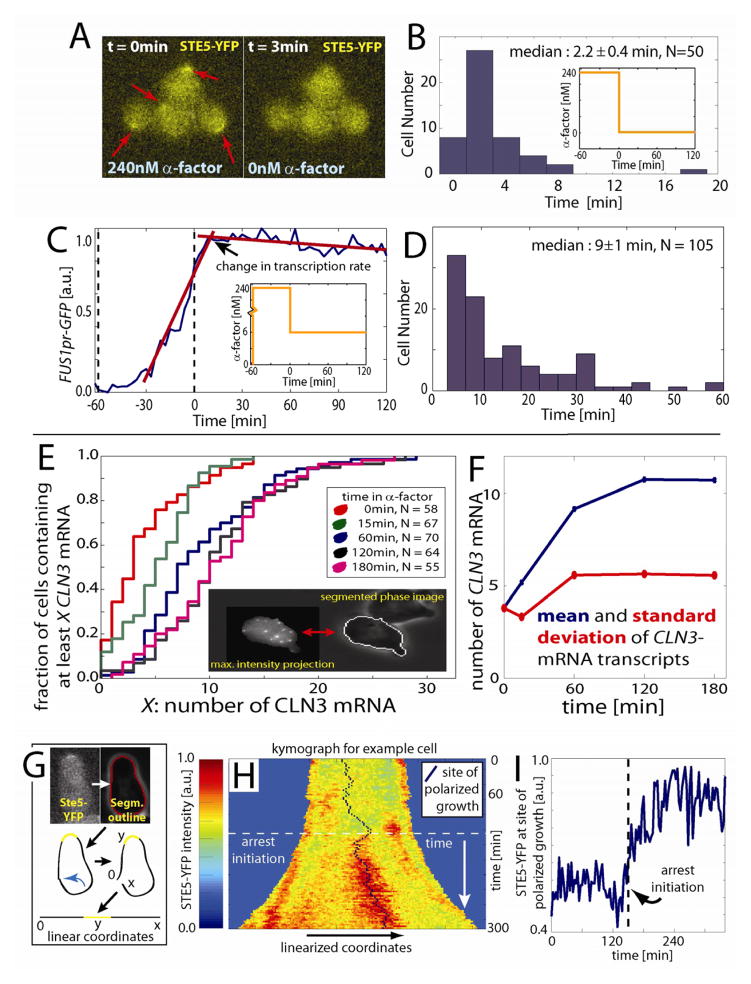

Figure 3.

Mating pathway activity is rapidly reversible and the cell cycle and MAPK pathways exhibit noise. (A) Micrographs of STE5-YFP cells before and after pheromone removal (red arrows indicate shmoo tips). (B) Histogram of the time of Ste5 membrane dissociation marking MAPK pathway inactivation. X-axis denotes time between pheromone removal and the disappearance of half the shmoo-tip associated Ste5-YFP (C,D) We used the pheromone-induced FUS1 promoter to drive expression of green fluorescent protein to measure the kinetics of mating pathway dependent transcription when cells arrested in 240nM α-factor were exposed to a step decrease to 6nM α-factor (C; inset). Time of transcription-rate change were measured (C) and displayed in a histogram (D) indicating rapid down-regulation of mating pathway dependent transcription. (E) Single molecule FISH was used to count the number of CLN3 mRNA in individual cells through a 3-hour pheromone arrest using maximal intensity projections of a z-stack (e.g., inset). (F) Both the mean and standard distribution of CLN3 mRNA increases during arrest. (G) STE5-YFP cells containing an integrated scaffold fusion protein were segmented and the boundary coordinates linearized. (H) Upon exposure to 3nM pheromone, Ste5-YFP is recruited to the membrane. Each horizontal line of the kymograph shows the YFP fluorescence at the membrane in the linearized coordinate system at a specific time. The length of the cell boundary increases with time; blue color denotes non-cell. (I) Example cell for which the level of Ste5 recruited to the shmoo tip fluctuates over the course of the pheromone arrest implying fluctuations in MAPK activity.

MAPK and cell cycle pathways exhibit noise

A hysteretic response to mating pheromone might act to buffer against fluctuations in activity in both the cell cycle and MAPK pathways. To estimate the potential variation in CDK activity, we measured the distribution of CLN3 mRNA in single cells using single molecule FISH (Raj et al., 2008). The number of mRNA transcripts (~5–10) is consistent with the previously observed size-independent variability in G1 duration arising due to intrinsic fluctuations associated with small numbers of molecules (Di Talia et al., 2007; Di Talia et al., 2009). Both the mean and standard deviation of the distribution of CLN3 mRNA molecules increased approximately 2-fold over the course of a pheromone arrest (Fig. 3E, 3F) consistent with previous reports (Wittenberg et al., 1990). Since Cln3 is a highly unstable protein with a half-life of less than 5 minutes (Tyers et al., 1992), we expect its concentration to track the mRNA level and therefore exhibit significant fluctuations (Paulsson, 2004). Therefore, both the average amount of Cln3 and the expected size of the largest Cln3 fluctuation increase over the course of a pheromone arrest. Thus, to remain arrested, the cell is required to raise the CDK threshold for cell cycle re-entry as we have observed.

In addition to noise in G1 cyclin levels, we suspected there might be temporal variation in the MAPK pathway activity. To test this hypothesis, we measured the amount of membrane associated scaffold protein (Ste5-YFP) in cells arrested in 3nM mating pheromone. We observed significant fluctuations in membrane associated Ste5-YFP (mean coefficient of variance = 0.17, N=67, Fig. 3G,H,I). Taken together, these results imply that significant fluctuations in both CDK and MAPK activity may also be counteracted by arrest reinforcement.

Feed-forward model for Far1 regulation

To gain insight into how the pheromone-induced MAPK pathway can fulfill the seemingly conflicting demands of rapid reversibility and reinforced arrest, we decided to model the Far1 feed forward regulation using differential equations. Our model of feed-forward regulation of Far1, consists of fast phosphorylation and slow transcription kinetics (see supporting material and Fig. S5 for a comprehensive analysis). The total amount of Far1 protein, Far1total, is the sum of active, Far1active, and inactive, Far1inactive, fractions. Far1 is made at a rate f0 [α(t)], which is a function of the extracellular pheromone concentration a(t). Far1 is diluted or degraded at a rate k2 Far1total (Fig. 4A,B), so that

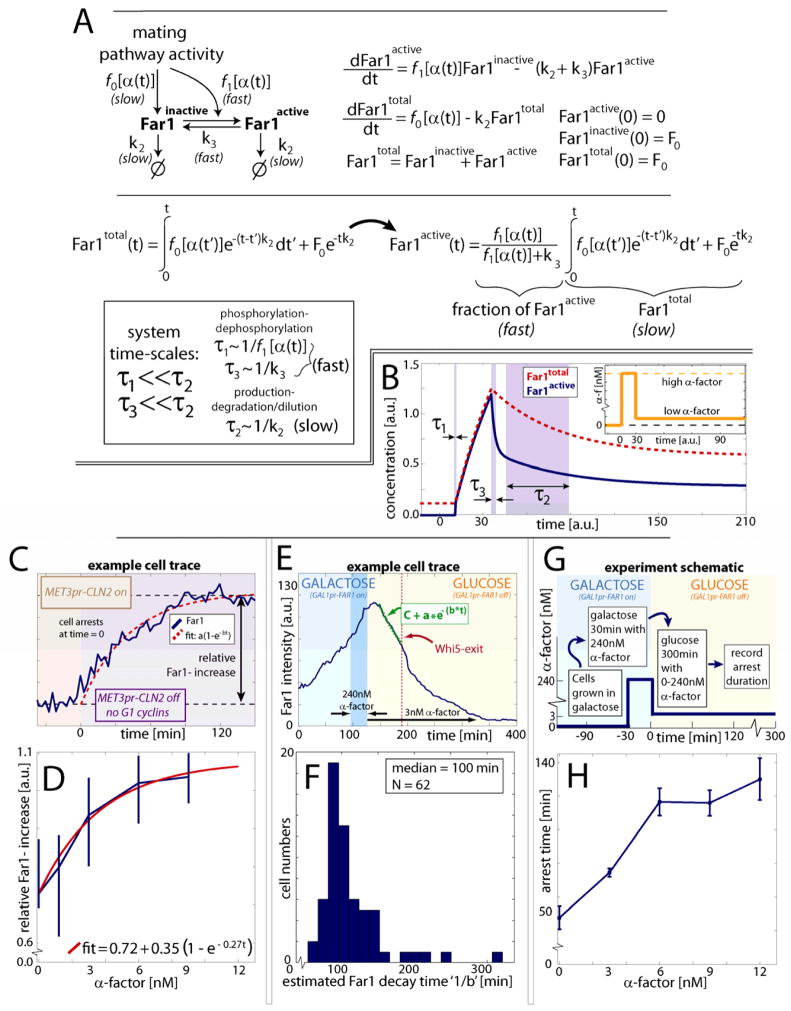

Figure 4.

Feed-forward model for Far1 synthesis and activation. (A) A mathematical model and analytical solution for feed-forward regulation of Far1 (see text). A separation of fast phosphorylation, τ1, and dephosphorylation, τ3, time scales relative to a slow synthesis, τ2, timescales allows a simplification of the expression for Far1active. (B) Solution for total and active Far1 illustrating the response to two step-changes in pheromone concentration (inset). (C) Far1-Venus expression was measured in G1 arrested cln1Δcln2Δcln3Delta; M ET3pr-CLN2 cells exposed to a range of pheromone concentration. (D) Median increase in Far1-Venus ± 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals as a function of pheromone concentration. N0nM=20, N1.2nM=21, N3nM=26, N6nM=26 and N9nM=15. (E) Cells with their endogenous Far1 promoter preplaced by a GAL1 promoter (cf Fig. 6A) were grown in galactose and exposed to a brief (30min) pulse of 240nM α-factor after which the carbon source was shifted to glucose media containing 3nM mating pheromone (GAL1pr-FAR1-Venus off). (F) Histogram of Far1-Venus concentration half-life estimates suggests Far1 is stable and diluted by cell growth. An exponential function was fit to the Far1 decay curve between the time of initial Far1 decrease and Whi5-nuclear exit (red dashed line). (G) Schematic of experiment to measure arrest duration in cells containing equivalent amounts of Far1 protein exposed to different pheromone concentrations. (H) Arrest duration (mean ± s.e.m.) for cells treated as shown in G. N0nM = 28, N3nM = 96, N6nM = 43, N9nM = 40 and N12nM = 28.

| (1) |

which after specification of the initial conditions Far1total(t=0)=F0, and Far1active(t=0)=0, can be solved to yield

| (2) |

Next, we aimed to determine the transcription rate of Far1 as a function of pheromone concentration, i.e., f0 [α(t)]. To measure FAR1 transcription, we constructed a strain that contains a FAR1-Venus fluorescent fusion protein and arrests in G1 on media containing methionine (MET3pr-CLN2Δcln1Δcln2Δcln3Δ). Cells were arrested in G1 prior to pheromone exposure and the concentration of Far1-Venus was tracked in individual cells through time (Fig. 4C,D). G1 arrested cells not exposed to any pheromone expressed Far1 at a surprisingly high rate (~70% of the maximum). Additional Far1 expression was dosage dependent with an EC50 ~ 3nM.

To determine the stability of Far1 protein during pheromone arrest, we placed Far1-Venus expression under control of the galactose inducible GAL1 promoter (GAL1pr-FAR1-Venus). Cells were grown in media containing galactose, exposed to 240nM mating pheromone, and then switched to media containing glucose and 3nM pheromone. Far1-Venus concentration decreased with a half-life ~100 minutes, consistent with the kinetics of dilution through cell growth suggesting that Far1 remained completely stable during pheromone arrest (Fig. 4E,F). Importantly, this surprising stability of Far1 during pheromone arrest validates our simplified model for the Far1 feed-forward loop where complex and integrated interactions including G1 cyclin activity are absent. Thus, feed-forward regulation can likely be considered insulated (Patterson et al., 2010) until cell cycle progression leads to the increase in the activity of the downstream B-type cyclins whose transcription is activated by Cln3 (Oehlen et al., 1998).

The stability of Far1 allows us to exploit the separate time scales of phosphorylation and growth to simplify our analysis (see supporting material for the case with not well separated time scales). Far1 is activated by phosphorylation at a rate proportional to Fus3 activity, f1[α(t)], and dephosphorylated by a constitutive phosphatase at a rate, k3 giving:

| (3) |

Since phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are rapid relative to protein synthesis and dilution, equation (2) will reach equilibrium so that

| (4) |

which can be rearranged and combined with equation (2) to yield:

| (5) |

To gain insight into how the active fraction of the total Far1 changes with pheromone concentration, we decided to examine cell cycle re-entry kinetics in a variety of pheromone concentrations for cells having the same amount of Far1 protein. To do this, we exposed cells, containing Far1 under exclusive control by the GAL1 promoter, to 240nM mating pheromone while growing in galactose, and then switched to glucose media containing a variable amount of pheromone (Fig. 4G,H). Next, we measured the duration of pheromone arrest as a function of the final pheromone concentration. Arrest duration increased steadily until saturation at ~6–9nM pheromone, again suggesting an EC50 ~ 3nM similar to that for FAR1 transcription. Taken together, our results support the alignment of MAPK activity and pheromone-induced transcription dose response curves, which has been suggested to improve the transmission of information through the MAPK pathway (Yu et al., 2008)

The solution of our model for a step increase followed by a step decrease in pheromone is informative (Fig. 4B, S5G). Upon the step increase, the initial amount of Far1, F0, is phosphorylated rapidly at a rate ~ f1 [α(t)]. Thus, the non-zero initial condition for total Far1 identified by McKinney et al. (1993) is crucial for a rapid arrest in response to mating pheromone. Next, during the period of high pheromone activity, both total and active Far1 accumulate at the slower synthesis rate f0 [α(t)] to reinforce the arrested state. Finally, upon decreasing the pheromone concentration, Far1 is rapidly dephosphorylated at a rate k3 leading to a sharp drop in the active fraction that can result in rapid cell cycle reentry. Notably, Far1 is diluted at a rate k2 associated with cell growth. In conclusion, fast phosphorylation kinetics determines the proportion of active Far1 to allow rapid cell cycle arrest and reentry in response to pheromone removal, whereas slower, history-dependent synthesis underlies arrest reinforcement. Specifically, our model predicts that:

Far1 accumulates over the course of a pheromone arrest

The total amount of Far1 correlates with arrest stability

Removing pheromone-dependent FAR1 transcription removes hysteresis

Far1 accumulation underlies arrest stability

To test if Far1 accumulation might cause arrest reinforcement, we measured Far1 amounts in live cells expressing FAR1 fused with the Venus yellow fluorescent protein from the endogenous locus. This Venus fusion protein did not affect arrest kinetics (Fig. S6A,B). Upon addition of pheromone, Far1-Venus initially accumulated at a constant rate for over one hour before asymptotically approaching its final level (Fig. 5A, 5B). This matched the result from solving equation (2) for a step-increase in mating pheromone and assuming that the initial amount of Far1 is significantly less than the final concentration. Thus a model of constant synthesis rate balanced by a dilution rate due to cell growth fits the observed Far1-Venus accumulation curves (equation and fit shown in Fig. 5B). This suggests that the Far1 synthesis rate, and therefore the pathway activity, is relatively constant through the course of a pheromone arrest and unaffected by transcriptional or post-transcriptional feedback on signaling components or changes in cell morphology.

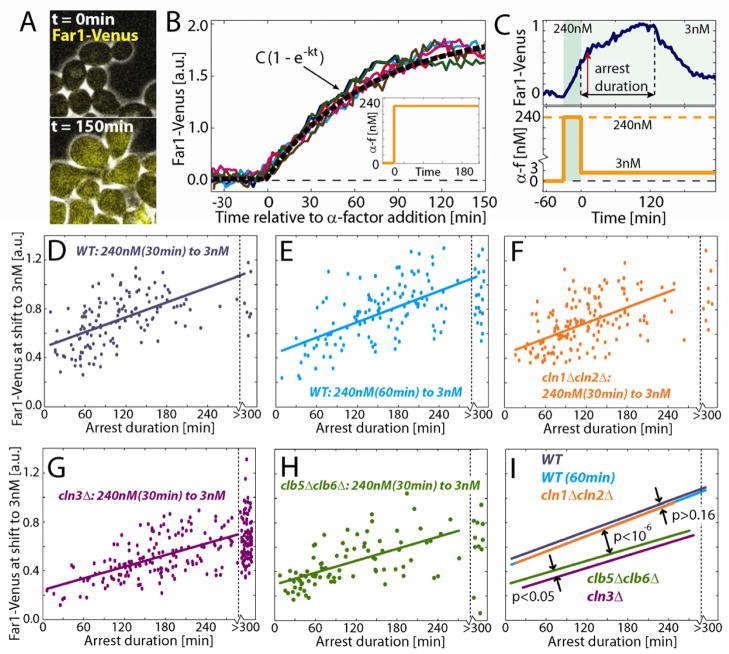

Figure 5.

Far1-Venus abundance correlates with arrest duration. (A) Composite phase and fluorescence images and (B) single-cell measurements of Far1-Venus in cells exposed to a step-increase in pheromone (inset). (C) Arrest duration (dashed lines determined by Whi5-mCherry nuclear residence) and Far1 abundance after the high pheromone pulse (red arrow) were measured. (D–I) Arrest duration correlated with Far1 abundance for WT, cln1Δcln2δ, cln3δ and clb5δ clb6δ cells experiencing 30 or 60 minute pulses of high pheromone. The R2 values for these correlations are as follows: WT(30min) = 0.32, WT(60min) = 0.37, cln1δcln2δ = 0.29, cln3δ = 0.35, clb5δclb6δ = 0.37.

Far1 amounts at the end of a high pheromone pulse show significant cell-to-cell variation due to differences in transcription rate and arrest duration (Colman-Lerner et al., 2005). Our model predicts that Far1-Venus levels will correlate with arrest stability. To test this, we examined arrest duration in cells experiencing a high-pheromone pulse followed by a lower 3nM pheromone concentration. We estimated the amount of Far1-Venus at the time of the step decrease in pheromone as the amount at the time when we detected a drop in the Far1-Venus accumulation rate approximately 50 minutes later (Fig. 5C and S6C). In agreement with our model, cells containing more Far1-Venus arrested longer (Fig. 5D and 5E; Table S2). A substantial amount of the residual variability in this relationship is due to cell size variation (Fig.S6D). However, cell type (mother or daughter) does not have a size-independent effect on reentry kinetics implying that differential expression of CLN3 due to the daughter-specific transcription factors Ace2 and Ash1 (Di Talia et al., 2009) is not maintained through a pheromone arrest.

In addition, the correlation between arrest duration and Far1 amount remained unchanged in cln1Δcln2Δ and WT cells, again implying that cell cycle reentry is primarily driven by Cln3 in competition with Far1 (Fig. 5F). Consistent with Cln3 as the main driver of cell cycle reentry, arrest of cln3Δ cells was approximately 2 hours longer than that of WT cells for the equivalent amount of Far1 (Fig. 5G, 5I and S6E). To test whether the observed insulation of Far1 in arrested cells (Fig. 4E,F) is related to the activation of the B-type cyclins, we also compared Far1 abundance and arrest duration in a strain lacking the S-phase cyclins CLB5 and CLB6 (Epstein and Cross, 1992; Schwob and Nasmyth, 1993). In agreement with this hypothesis we see that given the same amount of Far1, clb5Δclb6Δ cells arrest significantly longer than WT cells (Fig. 5H,I) demonstrating an important role for Clb5 and Clb6 at cell cycle reentry.

Our results so far suggest MAPK-induced FAR1 transcription is the molecular basis of history-dependent arrest reinforcement. Indeed, the relationship between Far1 abundance and arrest duration was unchanged by doubling the duration of the pheromone pulse from 30 to 60 minutes despite a significant increase in the mean arrest times (Fig. 5E). That cells with an equivalent amount of Far1-Venus, but different pheromone histories arrest for similar durations implies that history-dependence arises primarily from Far1 accumulation.

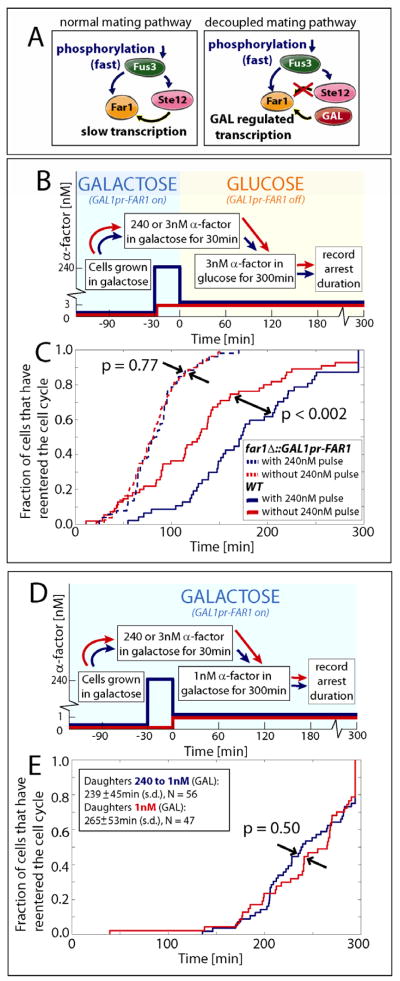

Decoupling FAR1 transcription from pheromone signaling removes history-dependence

To determine if Far1 transcription is the underlying mechanism for hysteresis, we decoupled FAR1 transcription from pathway activity by placing FAR1 under control of a galactose-inducible promoter (GAL1pr-FAR1; Fig. 6A). Importantly, this is the only FAR1 allele in this strain. Next, we repeated the hysteresis experiment (Fig. 2A) for cells that have equivalent amounts of Far1 but are exposed to different pheromone histories (Fig. 6B). Consistent with Far1-transcription underlying history-dependent cell cycle re-entry, GAL1pr-FAR1 cells did not exhibit hysteresis (Fig. 6C, S7A–C). To control for the potential effect of the FAR1 turnoff, we performed the same experiment with galactose as the sole carbon source using a lower final pheromone concentration (1nM) as the GAL1 promoter over-expresses FAR1 (Fig. 6D). Again, all history-dependence vanished (Fig. 6E, S7D,E). When FAR1 transcription is independent of pheromone concentration, cell cycle reentry kinetics are likely determined by current, not past, MAPK activity. Thus, we conclude that most if not all history-dependence in this cellular decision arises due to Far1 accumulation rather than the accumulation of any other Ste12 targets (Roberts et al., 2000).

Figure 6.

Exogenous pheromone-independent control of FAR1 transcription eliminates hysteresis. (A,B) Experiment schematic for the distributions of arrest duration shown in (C) for cells expressing FAR1 from the galactose inducible GAL1 promoter (GAL1pr-FAR1) and WT control cells. Upon the carbon source switch at t=0, Far1 synthesis is turned off. (D) Experiment schematic for the distributions of arrest duration shown in (E) for GAL1pr-FAR1 cells. In contrast to the results shown in (C), Far1 synthesis is constitutive throughout the experiment shown in (D,E). Results are shown for daughter cells only; similar results for mother cells are shown in Fig. S7. p-values were calculated using a Kolmogorov Smirnov test.

DISCUSSION

Isolation and interrogation of an embedded network motif

Understanding the potentially dynamic mechanisms underlying cellular decisions requires accurate measurement and control of input signals. Microfluidic devices coupled with fluorescence imaging allows such temporal control and quantification of signaling inputs (Berg and Block, 1984; Charvin et al., 2008; Gomez-Sjoberg et al., 2007; Hersen et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2008; Mettetal et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2009). Here, we temporally control the pheromone input signal to show that the decision to reenter the cell cycle is not solely based on MAPK pathway activity, but is also based on its integrated history.

Our empirical finding that a specific network motif embedded in a larger regulatory network can be independently analyzed and is responsible for cell cycle reentry control was not a priori obvious. Rather, one might expect that the multiple inhibitory interactions between Far1 and the G1 cyclins would necessitate a more complex model to analyze mating arrest. However, we found that negative regulation of Far1 by G1 cyclins was negligible during pheromone arrest and that Far1 inhibition is most likely executed by B-type cyclins implying that a modular analysis focusing exclusively on the feed-forward regulation of Far1 is valid all the way up to the point of B-type cyclin activity. This hopeful result suggests that signal processing properties of specific network motifs may be usefully applied even within the context of much more complex regulatory networks.

Initial condition of non-zero Far1 allows fast activation

We find that coherent feed-forward regulation of Far1 ensures a robust yet rapidly reversible cellular state. Far1 accumulates slowly to ensure stability against fluctuations and size-dependent increases in Cln3 activity (Turner et al., 2012), whereas fast phosphorylation cycles allow rapid responses. Regulation of mating arrest is most similar to coherent feed-forward regulation with a logical AND gate previously analyzed theoretically by Mangan and Alon (2003). In that analysis, an initial condition of no output protein yields a solution in which both fast and slow positively regulating branches combine for slow activation and fast inactivation. In sharp contrast, the initial condition of non-zero Far1 in early G1 prior to pheromone exposure (McKinney et al., 1993) allows rapid activation above the threshold required for cell cycle arrest.

Feed-forward regulation balances tradeoffs

Feed-forward regulation may produce sign-sensitive delays, non-monotone responses, pulse generation, and fold-change detection (Yosef and Regev, 2011). Moreover, a recent study suggest the presence of widespread feed-forward regulation in yeast cell cycle control (Csikasz-Nagy et al., 2009). But, the physiological function of these proposed feed-forward networks remains to be tested experimentally and transitions to reinforced cellular states have mostly been attributed to positive feedback mechanisms, especially if the transition is irreversible (Charvin et al., 2010; Xiong and Ferrell, 2003).

In reversible cellular transitions, feed-forward regulation may provide a superior architecture to balance response kinetics and stability compared to positive feedback loops, which can be difficult to reverse. Moreover, even when positive feedback loops are reversible, as in the case of mitosis, stable cellular states are generated through bistability (Pomerening et al., 2003; Sha et al., 2003). Bistability implies a multi-valued input-output relationship that in turn, necessarily implies a loss of information about the input signal. In sharp contrast, feed-forward regulation does not compromise the linear input-output relationship measuring the extracellular environment through the entire duration of a pheromone arrest (Bush and Colman-Lerner, 2013; Paliwal et al., 2007; Takahashi and Pryciak, 2008; Yu et al., 2008). Thus, to the best of our knowledge, feed-forward regulation is the only network structure that achieves the twin aims of stability and reversibility with minimal tradeoffs (Fig. 7A, see supplementary material p3–8; Fig. S4,S8, Table S3,4).

Figure 7.

(A) Alternative models for Far1 control are unable to achieve all the physiological objectives associated with pheromone arrest. (B) Modular architecture of a cellular decision: a rapid sensing module measures extracellular pheromone, while a slow history-dependent decision module determines cell fate.

Separation of time scales and modularity

The era of genomics has produced an explosion of data on inter- and intra-signaling pathway protein interactions. Cellular networks appear highly interconnected, complex, and unlikely to be amenable to standard techniques. Yet, classical genetics and biochemistry have been successfully applied to individual isolated signaling pathways. This is likely due to two, often neglected, simplifying facts about biological regulatory networks. First, real chemical interactions have varying strengths in contrast to the common tendency to depict them as binary (either an interaction exists or not). If the activity of a signaling molecule with many upstream interactions could be determined by just one or two key regulators, the network can be effectively simplified by neglecting the weaker interactions. Second, networks often contain signaling events, such as phosphorylation (fast) and transcription (slow), which occur on separate time scales. From the point of view of fast events, slower events are essentially static and can be treated as such during mathematical analysis as shown in our analysis of Far1 regulation. The separation of timescales, a standard technique of applied mathematics, greatly simplifies differential equation analysis and clarifies the function of specific network interactions (Alexander et al., 2009; Bender and Orszag, 1999; Rust et al., 2007).

Here, the separation of time scales yields a modular network structure where the sensor module is independent from the decision-making module (Fig. 7B). The shortest time for a cell to arrest the cell cycle is determined by the fast phosphorylation rate of the initial Far1 by the MAPK Fus3. Similarly, the fastest time to reenter the cell cycle after pheromone arrest is determined by the fast dephosphorylation and inactivation of Far1. Arrest reinforcement is determined by the slower transcription and dilution rates. Had the kinetics of all these interactions been similar, the determination of arrest, reentry, and reinforcement kinetics would be much less modular. Intriguingly, since transcription is likely to be slower than phosphorylation for fundamental biochemical reasons within most signaling pathways, we expect to see much more time scale-dependent modularity.

In engineered systems, modularity is commonly used so that individual components perform a set of limited functions, whose few parameters can be independently and easily tuned. Within the context of cell signaling, a separation of time scales results in functional modularity of specific biochemical interactions and network motifs. That specific interactions can be associated with specific functions may allow evolution to quickly and independently select on multiple aspects of cell physiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microscopy, microfluidics and image analysis

We used a Cellasic flowcell with Y4C plates as described in (Doncic et al., 2011) unless denoted otherwise. WHI5-mCherry strains were exposed for 750ms using the Colibri 540-80 LED module at 25% power. FAR1-Venus was exposed 300ms using the Colibri 505 LED module at 25% power. Image analysis was performed as described in (Doncic et al., 2013). Far1-Venus at the pheromone shift (Fig. 5C–I) was taken as the point where the rate of accumulation changed (red arrow; Fig. 5C, S6), rather than the time of pheromone reduction, due to Venus maturation kinetics (Charvin et al., 2008). Single molecule FISH was performed as in (Raj et al., 2008) and mRNA numbers determined from maximal intensity projections of z-stacks containing 9 slices. All strains used are congenic with W303 (see Table S4). Arrest probabilities in Fig. 1D–F and Fig.S1 were calculated using logistic regression. Confidence intervals were calculated using 10000 bootstrapping iterations.

Measurement of cell cycle reentry

Cells were grown in the flowcell in SCD for at least 90min and then arrested in SCD + 240nM α-factor. After a 2h arrest, we switched the medium to SCD - met + 240nM α-factor to induce expression of exogenous Cln2 from an integrated MET3pr-CLN2 construct. Next, we switched the media back to SCD + 240nM α-factor, which ended the exogenous Cln2 pulse. We monitored the cells for an additional 2 hours to determine cell fate. Pulse durations varied between 9 and 45 minutes to express variable amounts of exogenous Cln2. For cells remaining arrested, the Whi5-GFP signal reverts to the pre-pulse level, and we define δ using the minimum amount of nuclear Whi5-GFP. For cells that commit, we define δ using the minimum Whi5-GFP value between 3 and 9 minutes after the end of the pulse, which corresponds approximately to the time (~5min) it takes to inactivate the MET3 promoter (Charvin et al., 2008). γ is defined as the nuclear Whi5-GFP amount at the time of methionine removal.

Hysteresis measurement

Pre-Start G1 durations for cells experiencing a pulse of high α-factor were measured from the time of the switch to the final α-factor concentration to the time (half-max) when Whi5 leaves the nucleus. For cells not experiencing the high pheromone pulse, we score the first pre-Start G1 duration after pheromone addition as the amount of time Whi5 spends in the nucleus (half-max to half-max; Whi5 nuclear entry precedes division by 6–9 minutes). Cells arrested at the movie limit were scored as being arrested for the full 294min (max arrest).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Pheromone arrest is reinforced by accumulation of the CDK inhibitor Far1

The decision to reenter the cell cycle is based on the history of MAPK activity

Coherent feed-forward regulation allows rapid reversibility and arrest stability

Sensing and decision making functions of the MAPK pathway are modular

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Amodeo, A. Colman-Lerner, F. Cross, R. Lee, M. Loog, P. Pryciak, E. Siggia, and C. Gomez for insightful comments, E. Lui and R. Yu for reagents, and J. Turner for assistance with the FISH assay. Research was funded by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the NIH (GM092925).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander RP, Kim PM, Emonet T, Gerstein MB. Understanding modularity in molecular networks requires dynamics. Sci Signal. 2009;2:pe44. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.281pe44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon U. Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazsi G, van Oudenaarden A, Collins JJ. Cellular decision making and biological noise: from microbes to mammals. Cell. 2011;144:910–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender CM, Orszag SA. Advanced mathematical methods for scientists and engineers. New York: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Berg HC, Block SM. A miniature flow cell designed for rapid exchange of media under high-power microscope objectives. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2915–2920. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-11-2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush A, Colman-Lerner A. Quantitative measurement of protein relocalization in live cells. Biophys J. 2013;104:727–736. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F, Herskowitz I. Identification of a gene necessary for cell cycle arrest by a negative growth factor of yeast: FAR1 is an inhibitor of a G1 cyclin, CLN2. Cell. 1990;63:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvin G, Cross FR, Siggia ED. A microfluidic device for temporally controlled gene expression and long-term fluorescent imaging in unperturbed dividing yeast cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvin G, Oikonomou C, Siggia ED, Cross FR. Origin of irreversibility of cell cycle start in budding yeast. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman-Lerner A, Gordon A, Serra E, Chin T, Resnekov O, Endy D, Pesce CG, Brent R. Regulated cell-to-cell variation in a cell-fate decision system. Nature. 2005;437:699–706. doi: 10.1038/nature03998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M, Nishikawa JL, Tang X, Millman JS, Schub O, Breitkreuz K, Dewar D, Rupes I, Andrews B, Tyers M. CDK activity antagonizes Whi5, an inhibitor of G1/S transcription in yeast. Cell. 2004;117:899–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikasz-Nagy A, Kapuy O, Toth A, Pal C, Jensen LJ, Uhlmann F, Tyson JJ, Novak B. Cell cycle regulation by feed-forward loops coupling transcription and phosphorylation. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:236. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin RA, McDonald WH, Kalashnikova TI, Yates J, 3rd, Wittenberg C. Cln3 activates G1-specific transcription via phosphorylation of the SBF bound repressor Whi5. Cell. 2004;117:887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Talia S, Skotheim JM, Bean JM, Siggia ED, Cross FR. The effects of molecular noise and size control on variability in the budding yeast cell cycle. Nature. 2007;448:947–951. doi: 10.1038/nature06072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Talia S, Wang H, Skotheim JM, Rosebrock AP, Futcher B, Cross FR. Daughterspecific transcription factors regulate cell size control in budding yeast. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doncic A, Eser U, Atay O, Skotheim JM. An algorithm to automate yeast segmentation and tracking. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doncic A, Falleur-Fettig M, Skotheim JM. Distinct interactions select and maintain a specific cell fate. Mol Cell. 2011;43:528–539. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein CB, Cross FR. CLB5: a novel B cyclin from budding yeast with a role in S phase. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1695–1706. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrenton LS, Braunwarth A, Irniger S, Hurt E, Kunzler M, Thorner J. Nucleus-specific and cell cycle-regulated degradation of mitogen-activated protein kinase scaffold protein Ste5 contributes to the control of signaling competence. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:582–601. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01019-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner A, Jovanovic A, Jeoung DI, Bourlat S, Cross FR, Ammerer G. Pheromonedependent G1 cell cycle arrest requires Far1 phosphorylation, but may not involve inhibition of Cdc28- Cln2 kinase, in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3681–3691. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Sjoberg R, Leyrat AA, Pirone DM, Chen CS, Quake SR. Versatile, fully automated, microfluidic cell culture system. Anal Chem. 2007;79:8557–8563. doi: 10.1021/ac071311w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell LH, Culotti J, Pringle JR, Reid BJ. Genetic control of the cell division cycle in yeast. Science. 1974;183:46–51. doi: 10.1126/science.183.4120.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henchoz S, Chi Y, Catarin B, Herskowitz I, Deshaies RJ, Peter M. Phosphorylation- and ubiquitin-dependent degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Far1p in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3046–3060. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersen P, McClean MN, Mahadevan L, Ramanathan S. Signal processing by the HOG MAP kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7165–7170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710770105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RJ, Jr, Desplan C. Stochastic mechanisms of cell fate specification that yield random or robust outcomes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:689–719. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukam D, Desplan C. Binary fate decisions in differentiating neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H. Systematic identification of cell cycledependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10171–10176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900604106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PJ, Helman NC, Lim WA, Hung PJ. A microfluidic system for dynamic yeast cell imaging. Biotechniques. 2008;44:91–95. doi: 10.2144/000112673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani HD. From a to [alpha]: yeast as a model for cellular differentiation. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2007. p. xii. [Google Scholar]

- Mangan S, Alon U. Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11980–11985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133841100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney JD, Chang F, Heintz N, Cross FR. Negative regulation of FAR1 at the Start of the yeast cell cycle. Genes Dev. 1993;7:833–843. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettetal JT, Muzzey D, Gomez-Uribe C, van Oudenaarden A. The frequency dependence of osmo-adaptation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2008;319:482–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1151582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA. Yeast cells recover from mating pheromone alpha factor-induced division arrest by desensitization in the absence of alpha factor destruction. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:1004–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehlen LJ, Jeoung DI, Cross FR. Cyclin-specific START events and the G1-phase specificity of arrest by mating factor in budding yeast. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;258:183–198. doi: 10.1007/s004380050722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehlen LJ, McKinney JD, Cross FR. Ste12 and Mcm1 regulate cell cycle-dependent transcription of FAR1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2830–2837. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal S, Iglesias PA, Campbell K, Hilioti Z, Groisman A, Levchenko A. MAPKmediated bimodal gene expression and adaptive gradient sensing in yeast. Nature. 2007;446:46–51. doi: 10.1038/nature05561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JC, Klimenko ES, Thorner J. Single-cell analysis reveals that insulation maintains signaling specificity between two yeast MAPK pathways with common components. Science signaling. 2010;3:ra75. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsson J. Summing up the noise in gene networks. Nature. 2004;427:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature02257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter M, Gartner A, Horecka J, Ammerer G, Herskowitz I. FAR1 links the signal transduction pathway to the cell cycle machinery in yeast. Cell. 1993;73:747–760. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90254-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerening JR, Sontag ED, Ferrell JE., Jr Building a cell cycle oscillator: hysteresis and bistability in the activation of Cdc2. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:346–351. doi: 10.1038/ncb954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, van den Bogaard P, Rifkin SA, van Oudenaarden A, Tyagi S. Imaging individual mRNA molecules using multiple singly labeled probes. Nat Methods. 2008;5:877–879. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CJ, Nelson B, Marton MJ, Stoughton R, Meyer MR, Bennett HA, He YD, Dai H, Walker WL, Hughes TR, et al. Signaling and circuitry of multiple MAPK pathways revealed by a matrix of global gene expression profiles. Science. 2000;287:873–880. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust MJ, Markson JS, Lane WS, Fisher DS, O’Shea EK. Ordered phosphorylation governs oscillation of a three-protein circadian clock. Science. 2007;318:809–812. doi: 10.1126/science.1148596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob E, Nasmyth K. CLB5 and CLB6, a new pair of B cyclins involved in DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1160–1175. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha W, Moore J, Chen K, Lassaletta AD, Yi CS, Tyson JJ, Sible JC. Hysteresis drives cell-cycle transitions in Xenopus laevis egg extracts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:975–980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0235349100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skotheim JM, Di Talia S, Siggia ED, Cross FR. Positive feedback of G1 cyclins ensures coherent cell cycle entry. Nature. 2008;454:291–296. doi: 10.1038/nature07118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickfaden SC, Winters MJ, Ben-Ari G, Lamson RE, Tyers M, Pryciak PM. A mechanism for cell-cycle regulation of MAP kinase signaling in a yeast differentiation pathway. Cell. 2007;128:519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taberner FJ, Quilis I, Igual JC. Spatial regulation of the start repressor Whi5. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3010–3018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Pryciak PM. Membrane localization of scaffold proteins promotes graded signaling in the yeast MAP kinase cascade. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Falconnet D, Niemisto A, Ramsey SA, Prinz S, Shmulevich I, Galitski T, Hansen CL. Dynamic analysis of MAPK signaling using a high-throughput microfluidic single-cell imaging platform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3758–3763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813416106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JJ, Ewald JC, Skotheim JM. Cell size control in yeast. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyers M, Futcher B. Far1 and Fus3 link the mating pheromone signal transduction pathway to three G1-phase Cdc28 kinase complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5659–5669. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyers M, Tokiwa G, Nash R, Futcher B. The Cln3-Cdc28 kinase complex of S. cerevisiae is regulated by proteolysis and phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1992;11:1773–1784. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg C, Sugimoto K, Reed SI. G1-specific cyclins of S. cerevisiae: cell cycle periodicity, regulation by mating pheromone, and association with the p34CDC28 protein kinase. Cell. 1990;62:225–237. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90361-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Ferrell JE., Jr A positive-feedback-based bistable ‘memory module’ that governs a cell fate decision. Nature. 2003;426:460–465. doi: 10.1038/nature02089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeger-Lotem E, Sattath S, Kashtan N, Itzkovitz S, Milo R, Pinter RY, Alon U, Margalit H. Network motifs in integrated cellular networks of transcription-regulation and protein-protein interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5934–5939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306752101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef N, Regev A. Impulse control: temporal dynamics in gene transcription. Cell. 2011;144:886–896. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu RC, Pesce CG, Colman-Lerner A, Lok L, Pincus D, Serra E, Holl M, Benjamin K, Gordon A, Brent R. Negative feedback that improves information transmission in yeast signalling. Nature. 2008;456:755–761. doi: 10.1038/nature07513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.