Abstract

Background

Two psychological regulation strategies to cope with psychotic symptoms proposed by the cognitive behavioral tradition were examined in this study: cognitive reappraisal and experiential acceptance. Although cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis has increasing empirical support, little is known about the role of these two strategies using methods of known ecological validity.

Methods

Intensive longitudinal data was gathered from 25 individuals diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder with psychotic features. During the course of six days we measured contextual factors, psychotic and stressful events, psychological regulation strategies and functional outcome.

Results

Positive psychotic symptoms and stressful events had negative associations with quality of life and affect, whereas experiential acceptance had positive associations with them. Cognitive reappraisal had inconsistent associations with quality of life and no association with affect. Social interactions and engagement in activities had a positive association with quality of life. Results were supported by additional and exploratory analyses.

Conclusions

Across measures of functional outcome, experiential acceptance appears to be an effective coping strategy for individuals facing psychotic and stressful experiences, whereas cognitive reappraisal does not. Results suggest the need to further investigate the role of these psychological regulation strategies using ecologically valid methods in order to inform treatment development efforts.

Keywords: psychosis, cognitive reappraisal, experiential acceptance, quality of life, experience sampling method, cognitive behavior therapy

Introduction

In the last three decades, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) has made great strivings at showing its efficacy in the treatment of individuals with psychotic symptoms such as those from schizophrenic, schizoaffective, bipolar, and re-occurring major depressive disorders. Although the efficacy of CBT for psychosis has been questioned (Lynch, Laws, & McKenna, 2010), meta-analyses of these interventions show that they have a reliable effect size on a range of psychiatric symptoms (Wykes, Steel, Everitt, & Tarrier, 2008), they can substantially reduce levels of re-hospitalization (Bach & Hayes, 2002), and can be effective even among low functioning patients with schizophrenia (Grant & Huh, 2012).

Among CBT interventions for psychosis, two sharply contrasting strategies have been proposed for how to handle psychotic experiences. On the one hand, there are classic cognitive models for which psychotic experiences should be challenged and replaced with more realistic cognitions (i.e., Cognitive Therapy). On the other, new models encourage noticing and accepting psychotic experiences as a natural process of one’s mind, and to refocus on behavior (i.e., Acceptance and Commitment Therapy). However, to date, there has been little research contrasting these two strategies in a real-world setting.

Although there is strong evidence that CBT for psychosis is efficacious, little is known about the key ingredients of these interventions (Morrison et al., 2012; Wykes et al., 2008) and more generally about the daily psychological coping strategies used by this population in order to cope with stressful cognitive and sensory experiences. In a seminal paper, Lazarus and Alfert (1964) argued that cognitive reappraisals are crucial to individual’s perception of threat, and research has shown that in their absence individuals tend to experience more negative affect and reduced well-being (Gross & John, 2003; John & Gross, 2004). Cognitive reappraisals have been described as “a form of cognitive change that involves construing a potentially emotion-eliciting situation in a way that changes its emotional impact” (Gross & John, 2003, p. 349). More specifically, it has been argued that the thinking patterns of individuals with psychosis can contribute to the exacerbation or reduction of psychotic symptoms (Beck, 1952, 1979; Drury, Birchwood, Cochrane, & MacMillan, 1996). For example, Drury and colleagues emphasized the need to challenge negative evaluative beliefs (Drury et al., 1996), whereas Kuipers and colleagues referred to the importance of modifying dysfunctional schemas (Kuipers et al., 1997) in the psychological treatment of these disorders.

The relationship between cognitive reappraisal and a wide range of indicators of psychopathology and well-being has received broadly positive support in the emotion and clinical psychology literature (Gross & John, 2003); however, cognitive reappraisal as a treatment target has received more limited support (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012; Haeffel, 2010; Longmore & Worrell, 2007). In the area of psychosis, only one open trial has yet examined cognitive reappraisals as a mediator of outcome (Morrison et al., 2012) and further research is still needed to determine whether cognitive regulation is an effective strategy in coping with psychotic experiences (Morrison et al., 2012; Wykes et al., 2008).

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2011) is among the newer forms of CBT that take a different view of the role of cognitions and their influence on psychiatric symptoms and functional outcome more broadly. ACT emphasizes behavioral and contextual regulation such as experiential acceptance, which is “the adoption of an intentionally open, receptive, flexible, and nonjudgmental posture with respect to moment-to-moment experience” that involves a “voluntary and values-based choice to enable or sustain contact with private experiences or the events that will likely occasion them” (Hayes et al., 2011, p. 77). Experiential acceptance refers to the non-reactive and mindful awareness of our ongoing stream of consciousness, and it is the opposite of experiential avoidance, which has been defined as individual’s unwillingness to remain in contact with particular private experiences (e.g., bodily sensations, emotions, thoughts, memories, behavioral predispositions) and individuals’ efforts to alter the form, frequency, or situational sensitivity of these experiences (Hayes et al., 2011).

The use of experiential acceptance strategies might be particularly relevant to psychotic populations, because it may reduce attention to and thus greater entanglement with the particularly intense and pervasive sensorial and cognitive experiences that characterize psychotic disorders. There have so far been three randomized trials of ACT for psychosis, each showing good outcomes (Bach & Hayes, 2002; Gaudiano & Herbert, 2006a; White, 2011). A recent reanalysis of the combined Bach and Hayes (2002) and Gaudiano and Herbert (2006a) datasets found that approximately three hours of ACT during hospitalization reduced rehospitalization rates for one year post release. A formal measure of experiential acceptance was not taken because none had yet been developed, however the re-hospitalization outcome was mediated by the increased ability to notice positive psychotic symptoms without believing them (Bach, Gaudiano, Hayes, & Herbert, in press; Gaudiano, 2010; Gaudiano & Herbert, 2006b).

Given the emerging research on experiential and emotional avoidance as a core process in many forms of psychopathology (Barlow et al., 2010; Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, & Follette, 1996) and the need to examine cognitive reappraisal further in psychotic populations, the present study examined whether experiential acceptance as a form of behavioral regulation would have a stronger association with functioning in individuals with psychotic symptoms as compared to cognitive reappraisal as a form of emotional and cognitive regulation. Because individuals with psychotic symptoms have significant cognitive deficits and recall bias (Elvevåg & Goldberg, 2000) it seems especially important to use methods with this population that have high ecological validity (Ben-Zeev, 2012).

The experience sampling method (ESM; Hektner, Schmidt, & Csíkszentmihályi, 2007) reduces the gap between the experiencing of psychological or contextual events and the time of reporting them, and has the potential to examine the dynamic relationship between moment to moment processes and context in a less biased fashion. In the area of psychosis, researchers started to use ESM more than two decades ago (Delespaul & deVries, 1987). Programmable watches and pagers were initially used to gather psychotic symptoms and contextual data, and over time, electronic devices were adopted to electronically prompt participants and gather time stamped data (e.g., Kimhy et al., 2006). Most ESM research in that area has focused on contextual factors associated with psychotic symptoms and mood (e.g., Delespaul, deVries, & Van Os, 2002; Myin-Germeys, Nicolson, & Delespaul, 2001; Oorschot, Kwapil, Delespaul, & Myin-Germeys, 2009). In a more recent study, experiential avoidance had an association with poor self-esteem and increased paranoid thinking in a non-clinical sample of individuals (Udachina et al., 2009). However, to our knowledge the present study is the first that used an intensive longitudinal design (ESM) to explore in a clinical sample of individuals with severe psychopathology the interplay between psychotic experiences, the psychological coping strategies discussed above, and functional outcome.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from a program of assertive community treatment (PACT) at a state funded adult mental health institution of the United States that serves a large proportion of the population of northern Nevada. Individuals were eligible for the current study if they met diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective, bipolar and recurrent depressive disorder with psychotic features in addition to functional limitations in three or more of the following areas: vocational, housing, social, financial, family, psychiatric, medical, community or educational. Those with a diagnosis of mental retardation, inability to conduct assessments due to acute medical condition or symptoms of florid psychosis that might need imminent intensive psychiatric treatment or hospitalization were not approached. A DSM-IV diagnosis of serious mental illness was determined by chart review of records of licensed psychiatrists and/or psychologists prior to inclusion in the study and verified with patient’s individual psychiatrist. Participants were receiving outpatient services through the PACT program, but none of them was receiving psychotherapy during study completion.

Thirty nine individuals were invited to participate in the study. Their race and ethnicity was reported as Caucasian (80%), Asian (8%), African American (4%), and Latino (8%). Those who refused to participate (n = 8) did not differ from those enrolled with regards to age (t9.172 = .339, p = .742), sex (χ2(1) = 0.444, p = .212), or Global Assessment of Functioning score (t9.645= −.277, p = .787), however, they differed in psychiatric diagnosis: the majority of individuals in the group of subjects who refused to participate had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (t21.882= 2.722, p = .012). One participant was unable to follow study procedures and to respond to daily surveys, so data for this participant was not collected. Finally, five participants did not comply with the study procedure, which was defined as responding less than the equivalent of one day of experience sampling assessments. Chart review of medical records indicated that none of the participants had received either acceptance-based or cognitive-based cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis at the institution. The final sample included 25 participants (descriptive information can be found in Table 1). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Nevada, Reno.

Table 1.

Demographic information in our final sample (N = 25)

| Variable | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Age | M = 45 (SD = 12.76) |

| Gender | 60% male |

| Race | 80% White |

| Education | 65.2% some college but not degree |

| Marital status | 69.6% single or never married |

| Employment | 100% unemployed |

| Living Situation | 34.8% lived alone / 21.7% group home / 13% alone with provider support |

| Diagnosis | Schizophrenia (n = 7) |

| Schizoaffective (n = 14) | |

| Bipolar (n = 1) | |

| Any psychotic features (n = 3) | |

| GAF | M = 51.13 (SD = 11.29) |

| S-QOL-18 | M = 62.87 (SD = 15.7262) |

Note. GAF: Global assessment of functioning; S-QOL-18: Short Quality of Life Scale-18; M = mean; SD = Standard Deviation.

Measurement

Experience Sampling Measurements

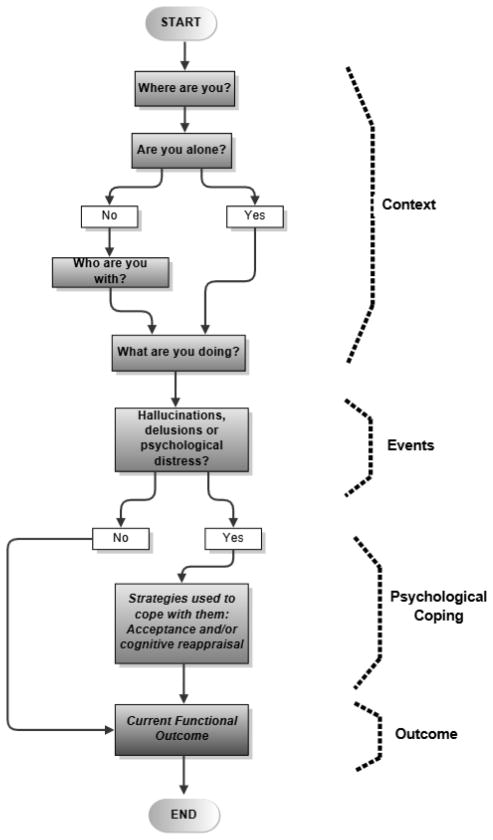

A flowchart of the ESM procedure can be found in Figure 1, and a summary of the ESM items utilized and their response range can be seen in Table 2. ESM assessment covered these domains: Current context, number of interactions, psychotic experiences or stressful events, psychological coping, and functional outcome. Items for current context and for psychotic experiences were adapted from previous research examining contextual factors (Delespaul, deVries, & van Os, 2002) and psychotic experiences (Granholm, Loh, & Swendsen, 2008; Kimhy et al., 2006). An item measuring the occurrence of internal or external stressful events was added in order to assess individual’s coping strategies in response to them.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of ESM procedure.

Table 2.

Sample of Relevant Experience Sampling Questions.

| Thematic Category | Question | Response options |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual factors | What are you doing at this moment? (Box Check) | Doing nothing Eating, dressing, hygiene Shopping, chores, cooking Work/school Leisure Healthcare Other |

| Since the last questionnaire, about how many times have you talked to another person? | Zero interactions One interaction Two or three interactions Four or more interactions |

|

| Psychotic or other Events | Since the last survey, did any of the following things happen to you? (Check all that apply) | I heard things that others could not hear (Auditory Hallucinations) I saw things that others could not see (Visual Hallucinations) I felt that someone was spying or plotting against me (Paranoia) I felt that people could read my thoughts (Mindreading) I felt possessed or controlled by someone or something (Thought Insertion) I felt that someone could communicate with me thru the TV/radio (Thought Broadcasting) I felt I had special powers to do something nobody else could do (Grandiosity) I felt stressed (Stressful event) None of the above |

| Psychological Coping | What did you do? | (7-point scale) |

| Cognitive Reappraisal | I made myself think about it in a way to make me stay calm | 0 (not at all) – 6 (completely) |

| Experiential Acceptance | I simply noticed my feelings and continued with what I was doing | 0 (not at all) – 6 (completely) |

| Positive and Negative Affect | Which emotion do you feel most strongly right now (Box Check) | Down Guilty Relaxed Anxious Happy Cheerful Lonely Satisfied None of the above |

| Quality of life | How are you doing right now? | (7-point scale) |

| Anhedonia | I enjoy what I’m doing | 0 (not at all) – 6 (completely) |

| Self-esteem | I feel competent | 0 (not at all) – 6 (completely) |

| Perceived social support | I feel connected to others | 0 (not at all) – 6 (completely) |

| Autonomy | I feel free to act | 0 (not at all) – 6 (completely) |

| Physical well-being | I have energy | 0 (not at all) – 6 (completely) |

| Self-esteem | I am comfortable with myself | 0 (not at all) – 6 (completely) |

Participant’s psychological coping strategies were assessed only if they had experienced a recent psychotic or stressful event. The cognitive reappraisal item was modeled from item 6 of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003). Similar adaptations of these items have been used by other researchers (e.g., Kashdan, Barrios, Forsyth, & Steger, 2006). This item had factor loadings that ranged from .32 to .71 in a cognitive reappraisal factor (Gross & John, 2003). The experiential acceptance item was adapted from item 2 of the acceptance subscale of the Voices Acceptance and Action Scale (Farhall, Ratcliff, Shawyer, & Thomas, 2010), which had a factor loading of .54 on acceptance. The order of presentation of these two items was randomized.

Participant’s functional outcome was assessed by current affectand quality of life questions. Affect quality was assessed using a box check in which they had to select the most representative affective state. Although using dichotomous ESM questions to measure affect deviates from previous ESM research (e.g., Myin-Germeys, Delespaul, & Van Os, 2005), our pilot data suggested that this strategy reduced assessment burden and appropriately captured the same emotional states. We assessed participants’ moment to moment quality of life (QOLe) using 6 items adapted from the Short Quality of Life Scale-18 (S-QoL-18; Boyer et al., 2010). These items measured individuals’ anhedonia, self-esteem, perceived social support, autonomy and physical well-being. An overall sum score of quality of life was aggregated from these items, with higher scores indicating higher quality of life. This scale ranged from 0 to 36 and had a Cronbach’s alpha of .81 in our sample.

Global Self-Report Measures

In contrast to QOLe, the S-QoL-18 (Boyer et al., 2010), and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) assessed global functional outcome and not moment to moment experience. The S-QoL-18 has good psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .72 to .84 (Boyer et al., 2010). Higher scores on this scale indicate higher global levels of quality of life. Participant’s GAFs were obtained from archival data and updated at the time of the study with case managers who had daily contact with patients. The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II; Bond et al., 2011) measured experiential avoidance which is considered at the other side of the spectrum of experiential acceptance. The AAQ-II consists of 7 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never true”) to 7 (“always true”). In our sample, this measure had a Cronbach’s alpha of .86. Higher scores on this scale indicate higher experiential avoidance. The cognitive reappraisal subscale of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ-R; Gross & John, 2003) assesses individual’s ability to modify and change emotions by changing one’s thoughts in order to cope with stress or difficult emotions. This subscale has 6 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). In our sample, this measure had a Cronbach’s alpha of .78. Higher scores on the reappraisal scale indicate higher levels of cognitive reappraisal. A global Likeability/usability Scale was provided to participants at the end of study participation (Kimhy et al., 2006). This scale measured feasibility and likeability issues such as difficulties to understand questions, interference with daily life, or stress due to study procedure. This scale had 9 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much”). Finally, demographic data was also obtained from medical records.

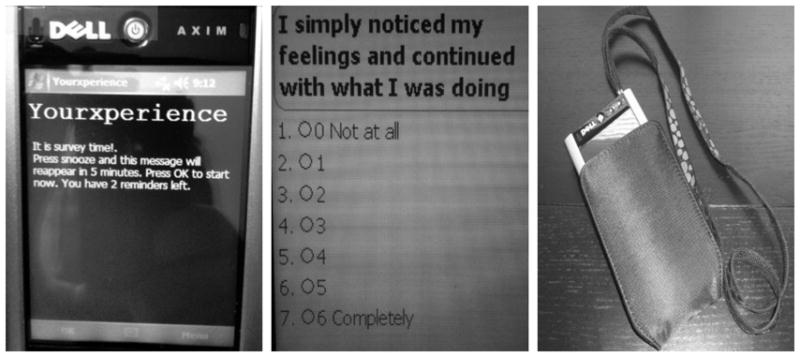

Procedure

After written informed consent, participants were administered the global self-report measures in a guided manner, which is common practice in research in this population. Since this was an observational study, each one of the psychological regulation strategies was explained to them without prompting their specific use. Then they were trained in the use of the experience sampling device and provided with a booklet with written instructions and pictures about how to problem solve common technical issues with the personal digital assistant (PDA). They were instructed to charge the PDA every night and to reset it on a daily basis and told that they would be contacted every day in order to monitor technical problems with the PDA. The PDAs were handheld Dell computers (model Axim X51) and had a protective case and a necklace (see Figure 2). Each device had Windows Mobile 5.0 installed and the experience sampling program MyExperience (Froehlich, Chen, Consolvo, Harrison, & Landay, 2007). No identifying information was kept on any of these devices, and the wireless capability of each device was disabled.

Figure 2.

Photographs of prompting survey message, item example and PDA case and necklace.

The ESM design was a random-signal-contingent-survey by blocks in which individuals were prompted three times per day, between 9:00 and 13:00, 13:00 and 17:00; and 17:00 and 21:00. Within each 4-hour block there were three separate survey prompts for nine total surveys per day, over a total of six days. If after the first signal the survey was not completed, two consecutive signals were followed within 5-minute intervals. If participant had not responded after a total of 15 minutes, the survey was cancelled. Thirty minutes was the minimum amount of time between surveys. In order to allow participants to skip surveys in situations in which they were unable to respond (e.g., during a doctor’s visit), a button was programmed to allow for that function. The maximum possible number of surveys per participant during the week was 54. Participants were compensated with a $10 Wal-Mart Gift card for participating in the study. To incentivize survey completion, participants were informed ahead of time that they would receive an additional $5 Wal-Mart gift card if they completed more than 80% of the experience sampling surveys.

Overview of Data Analysis

Given the intensive longitudinal data that was highly imbalanced in timing and number, multilevel linear (for quality of life) and logistic (for positive and negative affect) regressions were used to examine our research hypotheses (Gelman & Hill, 2007). Contextual covariates and indicators for psychotic and stressful events were included in an initial model, and a second model examined the additive effects of psychological coping strategies. Because coping strategies were only asked when participants experienced some sort of psychotic or stressful event (39.1% of total occasions), we averaged participant’s coping strategies as measured by our experience sampling items throughout the week, which allowed us to take full advantage of all of our experience sampling observations in our statistical models. Since this analytic strategy maximizes the use of all available data points in our outcome measures but undermines the role of specific moment to moment measures, we run additional exploratory analyses with the reduced subset of observations in which psychotic or stressful events occurred. The following are examples of the basic model and of the model with coping strategies, using the composite or mixed models form of multilevel regression equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where i indexes individuals and j indexes observations. Note that all covariates are time-varying and subscripts are not included for ease of presentation. To explore the association between these models and positive and negative affect, we built similar multilevel probabilistic logistic models:

| (3) |

| (4) |

P values and confidence intervals were fixed at the 95% level; however, due to relatively small sample size of this sample, estimates with p values smaller than .10 were interpreted as marginally statistically significant. To improve interpretation, covariates were centered on their mean. Models were compared using likelihood ratio chi-square tests, also called deviance tests (Singer & Willett, 2003).

Exploratory analyses were conducted in order to assess the strength of the observed associations by using global self-report measures of experiential avoidance (AAQ-II) and cognitive reappraisal (ERQ-R) and by narrowing down our analysis to observations in which psychotic or stressful events occurred (n = 268). Additional exploratory analyses were conducted using lagged regressions in order to explore temporal associations between quality of life and each one of our main covariates. These lags were defined as the immediate measurement period with the condition that they belonged to the same day. In these models, quality of life at time t was predicted from cognitive reappraisal and experiential acceptance at time t - 1 and vice versa. Due to small sample size of these lagged analyses, we were not able to enter quality of life at t - 1 as a covariate. This analytic strategy was also used to explore temporal associations between experiential acceptance and cognitive reappraisal. All analyses were conducted using the linear mixed effects lme4 package (Bates, Maechler, & Bolker, 2011) in R-2.14.1 (R Core Team, 2012). Confidence intervals and p values were extracted from each model with the package languageR (Baayen, 2011).

Results

We gathered 742 experience samples from a maximum of 1,350 possibly cued surveys (or 55%). Participants responded to an average of 30.8 surveys (SD = 11.8) during the course of the assessment period. Seventy percent were single or never married; none were employed, and the majority lived alone (35%, n = 8) or in a group home (22%, n = 5). Across experience samples, participants reported some type of psychotic experience on 22% of occasions, and some sort of stressful event on 17% of them. The most frequent form of hallucination was auditory (10%), (versus visual, 8%), and the most frequent forms of delusion were mind-reading, thought broadcasting and paranoid ideation (3% each). Frequencies and descriptive statistics for the main processes, outcomes and contextual factors are presented in Table 3. Participants score on the 9 items of the global likeability/usability scale, which ranged from 9 to 45, had a mean of 37.43 (SD = 5.53).

Table 3.

Psychotic experiences, psychological coping and quality of life as measured by the ESM

| Variable | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual factors | ||

| Doing nothing | 148 | 19.94% |

| Home of relative/friend | 106 | 14.28% |

| Zero Interactions | 202 | 27.22% |

| One Interaction | 220 | 29.64% |

| Two or three interactions | 232 | 31.26% |

| Four or more interactions | 92 | 12.39% |

| Psychotic experiences | 168 | 22.64% |

| Auditory hallucinations | 79 | 10.64% |

| Visual hallucinations | 60 | 8.08% |

| Paranoid delusions | 21 | 2.83% |

| Mind-reading | 21 | 2.83% |

| Thought insertion | 17 | 2.29% |

| Thought broadcasting | 21 | 2.83% |

| Grandiose delusions | 19 | 2.56% |

| Total hallucinations | 93 | 12.53% |

| Total delusions | 81 | 10.91% |

| Stressful event | 125 | 16.84% |

| Experiential Acceptance | M = 4.32 | SD = 1.86 |

| Cognitive Reappraisal | M = 3.60 | SD = 2.26 |

| Quality of Life | M = 28.50 | SD = 6.85 |

| Positive affect | 515 | 69.40% |

| Relaxed | 173 | 23.31% |

| Happy | 150 | 20.21% |

| Cheerful | 81 | 10.91% |

| Satisfied | 111 | 14.95% |

| Negative affect | 147 | 19.81% |

| Down | 22 | 2.96% |

| Guilty | 15 | 2.02% |

| Anxious | 72 | 9.70% |

| Lonely | 38 | 5.12% |

| Other Affect | 84 | 11.32% |

Note. Percentages are based on total number of signals, N=742. Variables quality of life, experiential acceptance and cognitive reappraisal were continuous so means (M) and standard deviations (SD) were reported.

The results of multilevel models for quality of life (based on Equations 1 and 2 above) are shown in Table 4. The experience of psychotic symptoms or stressful events had significant negative associations with QOLe–a decrease of approximately 0.3 SD for each. Moreover, being un-engaged in any activity (i.e., “doing nothing”) was similarly related to a decrease in QOLe of a similar magnitude, whereas social interactions generally and being at home of family / friends were significantly related to QOLe with magnitudes of 0.27 and 0.14 SD, respectively. The second model added individuals’ use of reappraisal and experiential acceptance as psychological regulation strategies. In this second model, experiential acceptance was significantly associated with QOLe (B = 2.7). A 1 SD change in (average) experiential acceptance (SD= 1.9) was associated with a predicted difference in QOLe of 4.9, which is approximately 0.71 SD change in QOLe. Cognitive reappraisal, on the other hand, was not significantly associated with QOLe. Based on the methods described by Snijders and Bosker (1999), the second model reported in Table 4 explained 42% of the variance of QOLe.

Table 4.

Multilevel linear regression of QOLe.

| Covariates | b | SE | t | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (deviance = 4455, n = 746) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Events | |||||

| Any Psychotic symptom | −1.789 | .563 | −3.178 | [−2.830, −.603] | .001** |

| Any Stressful event | −2.010 | .516 | −3.894 | [−3.143, −1.09] | .000*** |

| Contextual Factors | |||||

| Doing Nothing | −2.149 | .506 | −4.241 | [−3.080, −1.058] | .000*** |

| Home of relative/friend | .957 | .700 | 2.011 | [.047,2.791] | .044* |

| Number of Interactions | 1.909 | .196 | 4.868 | [.565,1.340] | .000*** |

|

| |||||

| Model 2 (deviance = 4242, n = 719, p = .000) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Events | |||||

| Any Psychotic symptom | −1.765 | .545 | −3.238 | [−2.811, −.665] | .001** |

| Any Stressful event | −1.962 | .500 | −3.919 | [−2.996, −1.05] | .000*** |

| Contextual Factors | |||||

| Doing Nothing | −2.126 | .496 | −4.283 | [−3.052, −1.10] | .000*** |

| Home of relative/friend | 1.546 | .678 | 2.280 | [.396, 3.051] | .022* |

| Number of Interactions | .779 | .194 | 4.006 | [.355, 1.123] | .000*** |

| Psychological Regulation | |||||

| Avg. Experiential Acceptance | 2.619 | .834 | 3.138 | [1.466, 3.844] | .001** |

| Avg. Cognitive Reappraisal | .198 | .668 | .297 | [−.747,1.149] | .766 |

Note. N = 25; b = unstandardized slopes; SE= standart error ; CI= confidence interval;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001,

p < .10

Next, we addressed the association between these two forms of psychological regulation and positive and negative affect. In a first model of Tables 5 and 6 we found that the occurrence of psychotic and stressful events decreased the odds of experiencing positive affect by 45% and 62%, respectively (i.e., OR of .55 and .38). Conversely the occurrence of psychotic and stressful events increased the odds of experiencing negative affect by 133% and 186%, respectively (i.e., OR of 2.33 and 2.86). In the second model of Tables 5 and 6, none of the contextual variables had a reliable association with negative affect; however, doing nothing had a marginally significant negative association with positive affect whereas number of interactions had a marginally significant positive association with positive affect. The occurrence of psychotic and stressful events remained a statistically significant predictor of positive and negative affect. Psychological regulation in the form of experiential acceptance decreased the likelihood of experiencing negative affect by .24 ORs, whereas it increased the likelihood of experiencing positive affect by 2.80. Cognitive reappraisal however, did not have a statistically significantly association with negative or positive affect.

Table 5.

Multilevel logistic regression of Positive Affect.

| Covariates | b | SE | z | p | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (deviance =686.2, n = 746) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Events | |||||

| Any Psychotic Symptom | −.595 | .289 | −2.056 | .039* | .551 |

| Any Stressful Event | −.950 | .280 | −3.393 | .000*** | .386 |

| Contextual Factors | |||||

| Doing Nothing | −.408 | .281 | −1.454 | .146 | .664 |

| Home of relative/friend | .031 | .396 | .078 | .937 | 1.031 |

| Number of Interactions | .256 | .112 | 2.278 | .022* | 1.292 |

|

| |||||

| Model 2 (deviance = 639.3, n = 719, p = .000) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Events | |||||

| Any Psychotic Symptom | −.617 | .287 | −2.147 | .031* | .539 |

| Any Stressful Event | −.921 | .279 | −3.299 | .000*** | .398 |

| Contextual Factors | |||||

| Doing Nothing | −.486 | .284 | −1.715 | .086† | .614 |

| Home of relative/friend | .086 | .389 | 0.222 | .823 | 1.090 |

| Number of Interactions | .217 | .115 | 1.882 | .059† | 1.243 |

| Psychological Regulation | |||||

| Avg. Experiential Acceptance | 1.030 | .312 | 3.299 | .000*** | 2.801 |

| Avg. Cognitive Reappraisal | .031 | .253 | .126 | .899 | 1.032 |

Note. N = 25; b = unstandardized slopes; SE= standart error ;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001,

p < .10

Table 6.

Multilevel logistic regression of Negative Affect.

| Covariates | b | SE | z | p | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (deviance = 560.4, n = 746) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Events | |||||

| Any Psychotic Symptom | .847 | .296 | 2.862 | .004** | 2.334 |

| Any Stressful Event | 1.054 | .297 | 3.541 | .000*** | 2.869 |

| Contextual Factors | |||||

| Doing Nothing | .171 | .311 | .552 | .581 | 1.187 |

| Home of relative/friend | .197 | .453 | .435 | .663 | 1.218 |

| Number of Interactions | −.116 | .127 | −.916 | .359 | .889 |

|

| |||||

| Model 2 (deviance = 509.2, n = 719, p = .000) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Events | |||||

| Any Psychotic Symptom | .907 | .295 | 3.070 | .002** | 2.478 |

| Any Stressful Event | 1.044 | .295 | 3.541 | .000*** | 2.842 |

| Contextual Factors | |||||

| Doing Nothing | .287 | .314 | .913 | .361 | 1.332 |

| Home of relative/friend | .147 | .444 | .331 | .740 | 1.158 |

| Number of Interactions | −.072 | .132 | −.545 | .585 | .930 |

| Psychological Regulation | |||||

| Avg. Experiential Acceptance | −1.409 | .342 | −4.120 | .000*** | .244 |

| Avg. Cognitive Reappraisal | .287 | .300 | 0.955 | .339 | 1.333 |

Note. N = 25; b = unstandardized slopes; SE= standart error;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001,

p <.10

In order to explore whether these models produced similar results when taking into account individual’s global tendency to use cognitive reappraisal and experiential avoidance, we run parallel multilevel regressions of quality of life and negative and positive affect using the AAQ-II and the ERQ-R while adjusting for the same covariates. Results indicated that experiential avoidance as measured by the AAQ-II had a statistically negative association with QOLe (B = −.40, SE= .07, 95% CI [−.52, −.28], p = .000), whereas cognitive reappraisal as measured by the ERQ-R had a non-statistically significant association with QOLe (B = .02, SE= .08, 95% CI [−.10, .15], p = .797). The AAQ-II was also statistically significantly associated with the likelihood of experiencing negative affect (B = .16, SE = .03, z = 4.86, 95% OR = 1.17, p = .000) and negatively associated with positive affect (B= −.14, SE = .03, z= −4.28, 95% OR = 1.02, p = .000), but the cognitive reappraisal subscale of the ERQ did not seem to have the same strength of association with either negative affect (b = .03, SE = .03, z = .84, 95% OR = 1.03, p = .399) or with positive affect (b = −.01, SE = .03, z= −.22, 95% OR = 1.03, p = .824).

The association between psychological coping and QOLe was also analyzed for the subgroup of observations in which participants experienced a psychotic or stressful event (n = 268). In this subset of data, acceptance and reappraisal were not averaged, and coefficients examine the association of outcomes and covariates measured at the same time point. Both psychological acceptance (b = .80, SE = .21, 95% CI [.53, 1.37], p = .000) and cognitive reappraisals (b = .41, SE = .20, 95% CI [.04, 1.37], p = .037) had statistically significant–and positive–associations with QOLe. In order to disambiguate these associations, we created models in which psychological coping preceded changes in QOLe and vice versa. Lagged scores of experiential acceptance, cognitive reappraisal and QOLe were created and then entered as covariates. If preceding levels of QOLe predicted psychological coping, this would suggest that these processes are a byproduct of QOLe and not vice versa. Conversely, changes in preceding levels of experiential acceptance or cognitive reappraisal would suggest that QOLe is a byproduct of those coping strategies. Results showed that on the one hand, experiential acceptance at time t – 1, predicted scores of QOLe at time t at a marginally statistically significant level (b =.49, SE = .25, 95% CI [.10, 1.17], p = .053), however, QOLe at time t – 1 did also marginally predict scores of experiential acceptance at time t (b = .03, SE = .01, 95% CI [.00, .08], p = .082). On the other hand, cognitive reappraisal at time t – 1 did not predict QOLe at time t (b = −.01, SE = .24, 95% CI [−.46, .47], p = .983), but QOLe at time t - 1 statistically significantly predicted scores of cognitive reappraisal at time t (b = .05, SE = .02, 95% CI [.006, .084], p = .02). Finally, we used the same lagged regression approach to explore predictive and temporal associations between both experiential acceptance and cognitive reappraisal. Results showed that cognitive reappraisal at time t – 1, did not predict scores of experiential acceptance at time t (b = −.02, SE = .07, 95% CI [−.16, .13], p = .838), and that experiential acceptance scores at time t – 1 did not predict scores of cognitive reappraisal at time t (b = −.06, SE = .08, 95% CI [−.21, .12], p = .429).

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, the study showed that among individuals with psychotic symptoms, behavioral regulation in the form of experiential acceptance had a stronger association with quality of life as compared to cognitive and emotional regulation, in the form of cognitive reappraisal. More fine grained analyses showed that cognitive reappraisal had a significant but weaker association with quality of life, but no association with positive and negative affect, whereas experiential acceptance had a reliable association with both of them. This study also showed that “doing something”, number of social interactions, and being at home of relative or friend were contextual factors that had a reliable association with quality of life but not with positive or negative affect. Our final model explained 42% of the variance of quality of life.

Additional exploratory analyses strengthened these results by indicating that global self-report measures of experiential acceptance and cognitive reappraisal had a similar pattern of associations. Furthermore, lagged-temporal analyses supported the pattern of associations between the two psychological coping strategies we compared, suggesting that experiential acceptance and quality of life might be mutually influencing each other, but that cognitive reappraisal might be a byproduct of quality of life and not vice versa. This study also explored temporal associations between cognitive reappraisal and experiential acceptance and suggested that experiential acceptance and cognitive reappraisal are two distinct processes. These lagged regressions need to be interpreted with caution, not only due to small sample size, but also to the fact that observations were not equally spaced across the assessment period and that neither quality of life, experiential acceptance nor cognitive reappraisal were experimentally manipulated.

Experiential acceptance is considered one of the core psychological processes of mindfulness and acceptance based therapies (Hayes et al., 2011) and of the unified protocol for anxiety and depression (Barlow et al., 2010). Thus this study provided empirical support for the role of such core process in this particular population as assessed by a more ecologically valid method of assessment. This acceptance approach is consistent with a larger body of literature that suggests that hearing voices is a ubiquitous phenomenon in both clinical and non-clinical populations (Honig et al., 1998) and that individuals who experience these symptoms with a more accepting stance tend not to develop a clinical disorder (Escher, Romme, Buiks, Delespaul, & Van Os, 2002a; Escher, Romme, Buiks, Delespaul, & van Os, 2002b; Romme & Escher, 2011). Cognitive reappraisals have been argued to be a core coping strategy related to general well-being and psychopathology (John & Gross, 2004), particularly among individuals with psychosis (Kuipers et al., 1997; Morrison et al., 2012; Oorschot, Kwapil, Delespaul, & Myin-Germeys, 2009). However, in this study cognitive reappraisal had a weak association with quality of life, and no association with positive or negative affect. Furthermore, quality of life seemed to predict individuals’ tendency to reappraise their experiences, and not vice versa. This study is not the first to question the role of cognitive reappraisals among individuals who experience challenging cognitive experiences, such as paranoia (Westermann, Kesting, & Lincoln, 2012). As discussed by Gross and John (2004), most of the research on cognitive reappraisals has focused on a few types of emotions, and it is therefore possible that this cognitive and emotional regulation strategy is not equally effective within this population. In addition, individual’s ability to successfully use cognitive reappraisal skills might be highly dependent on individuals’ participation in a therapeutic relationship. While this is probably true for many coping strategies, including experiential acceptance, the therapeutic relationship has been argued to be a critical component of CBT for psychosis (Mueser et al., 2002).

This study has implications for psychiatric and psychosocial treatments. The presence or absence of psychotic experiences is routinely assessed in inpatient and outpatient psychiatry settings. However, individuals’ coping mechanisms in response to them are barely examined in routine clinical practice, and most treatments for this population are psychopharmacological. The data in this study suggests that measurements of experiential acceptance could potentially inform clinical practice. Finally, because of the consistent associations we found between level of engagement in activities, social interactions and quality of life, the study supports the notion that a generally active and social lifestyle should also be encouraged and implemented among individuals with psychosis.

This study had a number of limitations that warrant a replication of these findings. First, future research would benefit from using larger and more representative experience samples of individuals with psychosis. Although multilevel linear modeling helped correct this bias, this did not completely solve the disproportionate number of surveys provided across individuals. Second, despite that ESM provides increasing levels of ecological validity as compared to traditional retrospective methods, our study design still involved some degree of recall bias (e.g., “Since the last survey, did any of the following things happen to you?”), and ultimately rendered observational and not experimental conclusions.

Third, in order to measure experiential acceptance and cognitive reappraisals, we also adopted a single item approach with the goal of reducing assessment burden and improve data quality. ESM is a flexible and adaptable methodological approach that encourages researchers to tailor measurement to the characteristics of the population being targeted (Hektner et al., 2007), which in this case involved the risk of assessment burden. However, future studies could benefit from exploring psychological regulation using a multi-item approach.

Forth, cognitive reappraisal and experiential acceptance strategies are often provided to patients in the context of CBT treatment packages that require regular monitoring and practice. However, in this observational study we assumed that some degree of each psychological regulation strategy existed in each individual’s repertoire. Previous research has documented the spontaneous use of both psychological regulation strategies by non-clinical populations without the need of instruction or involvement in therapy (e.g., Hayes et al., 1996; John & Gross, 2004). Thus in this study we did not intend to increase patient’s cognitive reappraisal and experiential acceptance skills but to simply capture these processes in their natural context.

Fifth, since the number of items on each branch was not balanced, and reporting psychotic or stressful symptoms increased the length of the ESM survey, the ESM branching structure might have encouraged individuals not to report psychotic symptoms over time. We chose to use this branching structure to minimize assessment burden, however, visual inspection of reported symptoms over time did not reveal any trend across subjects. Future studies might benefit from having a more balanced branching structure to avoid any possible bias. Finally, since the aim of the current study was to explore the role of specific psychological regulation strategies, we did not conduct a formal comparison of the incremental validity of ESM versus traditional global self-report measures in this population; however, future studies might consider such question.

To our knowledge, this study provides the first head to head comparison of the role of experiential acceptance and cognitive reappraisal as psychological regulatory strategies in the presence of psychotic experiences while using ecologically valid methods of measurement. More specifically, the findings provide support to targeting experiential acceptance as a core mechanism of change in CBT interventions for psychosis, and showed that this process had consistent and reliable associations with a variety of functional outcomes. Further research is needed in order to confirm these results and to inform future treatment development efforts in this population.

*Highlights.

We know little about the role of experiential acceptance and cognitive reappraisal in response to psychotic symptoms in natural/non-laboratory settings.

Across measures of functional outcome, experiential acceptance appears to have strong association with functional outcome in response to psychotic and stressful events

Across measures of functional outcome, cognitive reappraisal had inconsistent or no associations with functional outcome in response to psychotic and stressful events

Further research is needed to confirm these results and to inform treatment development efforts

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Roger Vilardaga, University of Nevada, Reno.

Steven C. Hayes, University of Nevada, Reno

David C. Atkins, University of Washington School of Medicine

Christie Bresee, Northern Nevada Adult Mental Health Services.

Alaei Kambiz, Northern Nevada Adult Mental Health Services.

References

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S. The influence of context on the implementation of adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;50(7–8):493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baayen RH. languageR: Data sets and functions with “Analyzing Linguistic Data: A practical introduction to statistics”. 2011 Retrieved from http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=languageR.

- Bach P, Gaudiano BA, Hayes SC, Herbert JD. Acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis: intent to treat, hospitalization outcome and mediation by believability. Psychosis. :1–9. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2012.671349. (in press) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bach P, Hayes SC. The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to prevent the rehospitalization of psychotic patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(5):1129–1139. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Allen LB, May JTE. Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders: Therapist Guide. 1. Oxford University Press; USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999375-42. 2011 Retrieved from http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4.

- Beck AT. Successful outpatient psychotherapy of a chronic schizophrenic with a delusion based on borrowed guilt. Psychiatry. 1952;15(3):305–312. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1952.11022883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zeev D. Mobile Technologies in the Study, Assessment, and Treatment of Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38(3):384–385. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, Waltz T, et al. Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42 (4):676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer L, Simeoni M-C, Loundou A, D’Amato T, Reine G, Lancon C, Auquier P. The development of the S-QoL 18: A shortened quality of life questionnaire for patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;121(1–3):241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delespaul P, deVries M. The daily life of ambulatory chronic mental-patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1987;175(9):537–544. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delespaul P, deVries M, van Os J. Determinants of occurrence and recovery from hallucinations in daily life. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2002;37(3):97–104. doi: 10.1007/s001270200000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury V, Birchwood M, Cochrane R, MacMillan F. Cognitive therapy and recovery from acute psychosis: A controlled trial .2. Impact on recovery time. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;169(5):602–607. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvevåg B, Goldberg T. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is the core of the disorder. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2000;14(1):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher S, Romme M, Buiks A, Delespaul P, Van Os J. Formation of delusional ideation in adolescents hearing voices: A prospective study. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2002a;114(8):913–920. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher S, Romme M, Buiks A, Delespaul P, Van Os J. Independent course of childhood auditory hallucinations: a sequential 3-year follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002b;181:S10–S18. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhall J, Ratcliff K, Shawyer F, Thomas N. The Voices Acceptance and Action Scale (VAAS): Further development. Symposium conducted at the World Congress of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Boston, United States. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich J, Chen MY, Consolvo S, Harrison B, Landay JA. MyExperience: a system for in situ tracing and capturing of user feedback on mobile phones. Proceedings of the 5th international conference on Mobile systems, applications and services, MobiSys ’07; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2007. pp. 57–70. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano BA. Is It the Symptom or the Relation to It? Investigating Potential Mediators of Change in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Psychosis. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(4):543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano BA, Herbert JD. Acute treatment of inpatients with psychotic symptoms using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Pilot results. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006a;44(3):415–437. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano BA, Herbert JD. Believability of Hallucinations as a Potential Mediator of Their Frequency and Associated Distress in Psychotic Inpatients. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006b;34(04):497–502. doi: 10.1017/S1352465806003080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, Loh C, Swendsen JD. Feasibility and validity of computerized ecological momentary assessment in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34(3):507–514. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P, Huh G. Randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of cognitive therapy for low-functioning patients with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):121–127. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(2):348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ. When self-help is no help: traditional cognitive skills training does not prevent depressive symptoms in people who ruminate. Behaviour research and therapy. 2010;48(2):152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. 2. Guilford Press; 2011. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(6):1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hektner JM, Schmidt JA, Csíkszentmihályi M. Experience sampling method: measuring the quality of everyday life. London: SAGE; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Honig A, Romme MaJ, Ensink BJ, Escher S, Pennings MHA, Devries MW. Auditory hallucinations: A comparison between patients and nonpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186(10):646–651. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199810000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(6):1301–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Barrios V, Forsyth JP, Steger MF. Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(9):1301–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimhy D, Delespaul P, Corcoran C, Ahn H, Yale S, Malaspina D. Computerized experience sampling method (ESMc): Assessing feasibility and validity among individuals with schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40(3):221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers E, Garety P, Fowler D, Dunn G, Bebbington P, Freeman D, Hadley C. London East Anglia randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for psychosis .1. Effects of the treatment phase. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;171:319–327. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Alfert E. Short-circuiting of threat by experimentally altering cognitive reappraisal. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1964;69:195–205. doi: 10.1037/h0044635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore RJ, Worrell M. Do we need to challenge thoughts in cognitive behavior therapy? Clinical psychology review. 2007;27(2):173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch D, Laws KR, McKenna PJ. Cognitive behavioural therapy for major psychiatric disorder: Does it really work? A meta-analytical review of well-controlled trials. Psychol Med Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(1):9–24. doi: 10.1017/S003329170900590X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AP, Turkington D, Wardle M, Spencer H, Barratt S, Dudley R, Brabban A, et al. A preliminary exploration of predictors of outcome and cognitive mechanisms of change in cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis in people not taking antipsychotic medication. Behaviour research and therapy. 2012;50(2):163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser K, Corrigan P, Hilton D, Tanzman B, Schaub A, Gingerich S, Essock S, et al. Illness management and recovery: A review of the research. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(10):1272–1284. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.10.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Nicolson N, Delespaul P. The context of delusional experiences in the daily life of patients with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31(3):489–498. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Van Os J. Behavioural sensitization to daily life stress in psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(5):733–741. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704004179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oorschot M, Kwapil T, Delespaul P, Myin-Germeys I. Momentary Assessment Research in Psychosis. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21(4):498–505. doi: 10.1037/a0017077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udachina A, Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Fitzpatrick S, O’Kane A, Bentall RP. Understanding the Relationships Between Self-Esteem, Experiential Avoidance, and Paranoia Structural Equation Modelling and Experience Sampling Studies. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2009;197(9):661–668. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b3b2ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Romme M, Escher S. Psychosis as a Personal Crisis an Experience-Based Approach. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis; 2011. Retrieved from http://public.eblib.com/EBLPublic/PublicView.do?ptiID=957449. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis : modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis : an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London; Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Westermann S, Kesting M-L, Lincoln TM. Being deluded after being excluded? How emotion regulation deficits in paranoia-prone individuals affect state paranoia during experimentally induced social stress. Behavior therapy. 2012;43(2):329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R. A feasibility study of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for emotional dysfunction following psychosis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49(12):901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: Effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34(3):523–537. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]