Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is an established treatment for dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (BE). Although short-term endpoints of ablation have been ascertained, there have been concerns about recurrence of intestinal metaplasia (IM) after ablation. We aimed to estimate the incidence and identify factors that predicted the recurrence of IM after successful RFA.

METHODS

We analyzed data from 592 patients with BE treated with RFA from 2003 through 2011 at 3 tertiary referral centers. Complete remission of intestinal metaplasia (CRIM) was defined as eradication of IM (in esophageal and gastro esophageal junction biopsies), documented by 2 consecutive endoscopies. Recurrence was defined as presence of IM or dysplasia after CRIM in surveillance biopsies. Two experienced gastrointestinal pathologists confirmed pathology findings.

RESULTS

Based on histology analysis, before RFA, 71% of patients had high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma, 15% had low-grade dysplasia, and 14% had non-dysplastic BE. Of patients treated, 448 (76%) were assessed following RFA. 55% of patients underwent endoscopic mucosal resection before RFA. The median time to CRIM was 22 months, with 56% of patients in CRIM by 24 months. Increasing age and length of BE segment were associated with a longer times to CRIM. Twenty-four months after CRIM, the incidence of recurrence was 33%; 22% of all recurrences observed were dysplastic BE. There were no demographic or endoscopic factors associated with recurrence. Complications developed in 6.5% of subjects treated with RFA; strictures were the most common complication.

CONCLUSION

Of patients with BE treated by RFA, 56% are in complete remission after 24 months. However, 33% of these patients have disease recurrence within the next 2 years. Most recurrences were non-dysplastic and endoscopically manageable, but continued surveillance after RFA is essential.

Keywords: esophageal cancer, prevention, endoscopic therapy, EAC

INTRODUCTION

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor lesion to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), a cancer that has a poor survival rate of <20% in 5 years1. The risk of EAC in patients with dysplastic BE continues to be higher compared to the general population2. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a well-recognized treatment modality for dysplastic BE2. Of the various modalities currently available, RFA is highly effective in treating dysplastic BE, and associated with low rates of complications3–12. This has resulted in increased use of RFA in the community and tertiary care setting. However, a major unresolved clinical question is whether continued surveillance is needed after successful RFA therapy. This is critical as patients being treated with RFA are potentially curable.

Cost efficacy models for ablative therapies have shown endoscopic therapy to be cost effective, as long as treatments are definitive and do not require future surveillance endoscopy13. This is particularly relevant for low grade (LGD) and non-dysplastic (ND) BE, in which the best management is unknown at this time. Studies show high rates of complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia (CRIM) and dysplasia with decreased progression to EAC in those treated with RFA3–7, 9–12. However, these findings are limited by the absence of prior endoscopic therapy before RFA (such as EMR) in a substantial proportion of subjects, small patient numbers, single center design and short-term follow-up. Thus, there is limited data on the durability of eradication and the ability to maintain remission of both dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia (IM) on a long-term basis11. Due to this lack of data, indefinite endoscopic surveillance has been recommended following CRIM, to monitor for recurrence of BE13, 14.

The goals of this study were to: 1. Determine predictors of achieving CRIM in patients treated with RFA; 2. Estimate the incidence of recurrent IM (with or without dysplasia) in a large multicenter cohort of patients treated with RFA; and 3. Assess the frequency of complications with RFA therapy.

METHODS

IRB approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University, University of Pennsylvania, and the Mayo Clinic Rochester.

Study Design

This is a cohort study of patients treated with RFA for BE associated dysplasia from three BE referral centers which are part of a Barrett’s Esophagus Translational Research Network (BETRNet) consortium, funded by the National Cancer Institute. This BETRNet consortium is comprised of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Columbia University, New York, New York. Data were collected from patients treated and followed in these centers from January 2003 to November 2011.

Patient assessment and treatment

Data were extracted from prospectively-maintained databases from each of the participating institutions. Inclusion criteria were: patients over the age of 18 with the presence of endoscopically (at least 1 cm endoscopically evident columnar mucosa in the tubular esophagus) and histologically-confirmed BE. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, had presence of esophageal varices, had only one endoscopy at the recruiting center with no repeat evaluation, or did not receive RFA treatment at the recruiting center. The application of RFA was performed by gastroenterologists that are experts in its application, using established standard clinical practice for managing BE and associated dysplasia.

All centers performed endoscopic evaluation of the BE segment with high-definition white light endoscopy and narrow band imaging (NBI) prior to endoscopic treatment. All patients could receive any endoscopic treatment prior to receiving RFA. This included endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy (PDT), argon plasma coagulation (APC), or multipolar coagulation (MPC). An EGD was performed after endoscopic treatments to confirm efficacy. All patients were on once or twice a day PPI therapy during and after ablation. If patients had nodular BE or histology of HGD/EAC, they received endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to exclude coexistent malignancy. Those with negative EUS findings received EMR with either the band technique15 (Duette, Cook Medical, USA) or the Cap technique16 (Olympus, USA).

All centers used circumferential and focal RFA to eradicate BE segments. The type of ablation catheter followed standard clinical practice with the circumferential balloon catheter being used for longer segments of circumferential BE, while focal therapy was rendered for small tongues and/or islands of BE. In addition to treating the original BE segment, all patients had ablation therapy directed to their gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). For those patients with histologic diagnosis of ND BE, an energy dose of 10 J/cm2 was administered to the targeted area. For those patients with LGD, HGD or EAC, an energy dose of 12 J/cm2 was administered as per company recommendations. Treatments with RFA were applied every 2–3 months until histologic and endoscopic remission was achieved. If a patient received RFA therapy and were pending follow up by the end of the study period, they were excluded from analysis.

CRIM was defined as histologic and endoscopic remission of IM (in esophageal and GEJ biopsies) after two consecutive endoscopies with biopsies taken every 1–2 centimeters in 4-quadrants with jumbo or large capacity forceps throughout the former BE segment length17. Recurrence was defined as the histologic presence of IM, with or without dysplasia, on biopsies taken from the esophagus and/or the GEJ after CRIM was achieved. Biopsy protocols were similar to those pre-CRIM.

All subjects who achieved CRIM remained on endoscopic surveillance. The frequency of endoscopy performed in the surveillance program was dependent on the original histology of BE treated. If the patient had ND or LGD pre-ablation, surveillance endoscopies were performed every 6 months for the first year and then every year thereafter. If the patient had HGD or EAC pre-ablation, they had surveillance endoscopies every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months the following year, and then every year thereafter. Endoscopic biopsies were performed to evaluate the histologic status of BE post treatment. Biopsies were taken from the esophagus along the original length of the BE segment, GEJ and any visible abnormalities detected as per protocol followed at the three participating institutions. Endoscopic location of recurrence, as well as dysplasia status for all patients was documented. All patients enrolled in the study were followed until the end of the study period on November 2011.

Histology

The histology on entry for all patients was the grade of dysplasia noted prior to delivering any endoscopic treatment. Histopathology of all tissue samples acquired on a patient was verified at the site of recruitment and treatment, and was confirmed by expert gastrointestinal pathologists. All three participating centers took biopsies of the GEJ and the length of the BE segment. However, not all sites reported histology of the tubular esophagus and GEJ separately. The worst grade of dysplasia detected at either location was the overall histologic grade assigned to that patient for that specific surveillance date. Similar measures were undertaken for biopsies obtained in CRIM and recurrence patients.

Statistics

Data was summarized as mean (±SD), median (interquartile range) or proportions (%), as warranted. Time to achieving CRIM (from start of RFA treatment) was summarized using the Kaplan Meier method and proportional hazards models were used to assess the association of several potential factors associated with time to CRIM. Similarly, the Kaplan Meier method was used to estimate the incidence of recurrence in those patients that had achieved CRIM. SAS® statistical software version 9.31 (SAS Inc, North Carolina) was used for the analyses.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

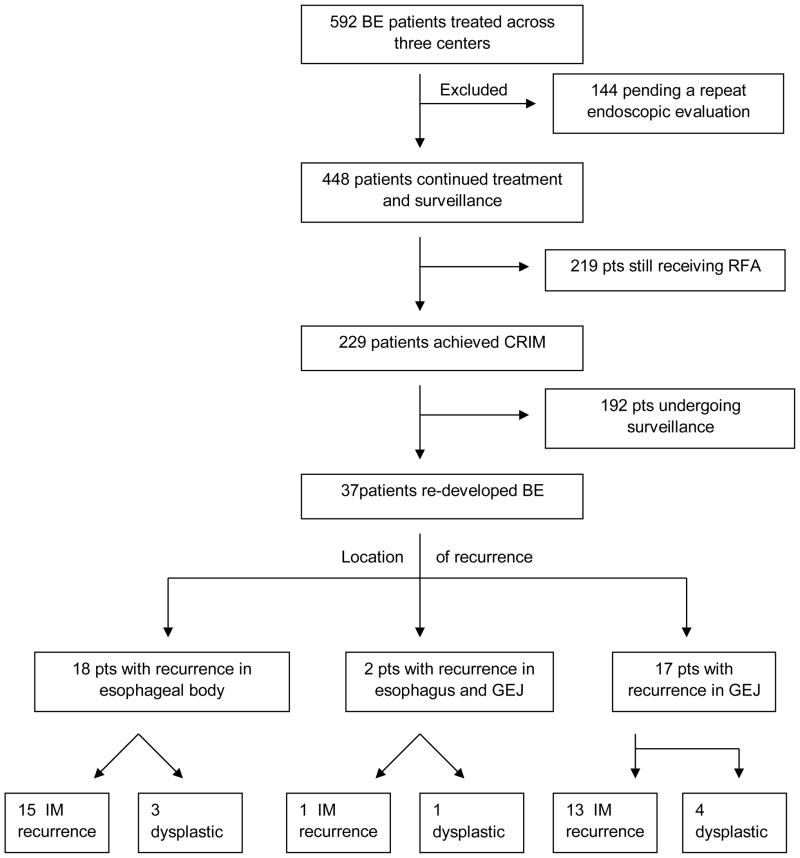

Patient flow in the study is shown in Figure 1. A total of 592 patients were treated with RFA. Of these patients, 144 were excluded from analysis as they received only one treatment of RFA and were pending follow up by the end of study period. Of the remaining 448 patients, the mean (SD) age was 64 (10) years and 85% were males. Demographics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean (SD) length of Barrett’s esophagus treated was 4.1 (3.1) cm. Dysplastic BE was the most common indication for ablation, with 86% having LGD, HGD or EAC. Specifically, 11% had intramucosal EAC, 60% HGD, 15% LGD and 14% NDBE. A majority of patients (55%) underwent EMR prior to RFA. A small number of patients had undergone cryotherapy (1%), APC/MPC (0.5%) and PDT (0.5%) prior to RFA. The remaining patient population (43%) did not receive any endoscopic therapy prior to RFA.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of All BE Patients Treated with RFA (GEJ = Gastroesophageal junction; IM = intestinal metaplasia)

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of All Patients Enrolled (N=448)

| Baseline Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Mean (±SD) Age in years | 64 ± 10 |

|

| |

| Male Gender | 85% |

|

| |

| Mean (±SD) BE Length in cm | 4.31 ± 3.1 |

|

| |

| Type of RFA applied: | |

| Circumferential ablation only | 13% |

| Focal ablation only | 49% |

| Both circumferential and focal ablation | 37% |

|

| |

| Pre RFA endoscopic interventions | |

| - EMR | 55% |

| - Cryotherapy | 1% |

| - APC/MPEC | 0.5% |

| - PDT | 0.5% |

Abbreviations used :

RFA : Radiofrequency ablation; EMR : endoscopic mucosal resection; APC : argon plasma coagulation; MPEC : multipolar electrocoagulation; PDT : Photodynamic therapy.

Complete Remission of Intestinal Metaplasia

For the 448 patients treated and followed post therapy, the median time (from start of RFA) to CRIM was 22 months. Approximately 26% of patients achieved CRIM by 1 year, 56% by 2 years and 71% by 3 years. Entry histology was not associated with the achievement of CRIM (p=0.98) (Table 2). Overall, pre-RFA treatment (including EMR) was not associated with time to CRIM (p=0.44). The median duration over which RFA treatments were delivered was 4 months (IQR 0–9). A total of 131 (29%) patients received 1 RFA treatment session, 158 (35%) patients received 2 treatment sessions, and the remaining patients received 3 to 10 treatment sessions before achieving CRIM. In the multiple variable regression model, younger age (p=0.005) and shorter segments of entry BE length (p=0.003) were associated with a shorter time to achieving CRIM (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of CRIM - Univariate and Multiple Variable Regression Models (N=448)

| Variable (N=448) | Proportional Hazards Multiple Variable Model | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | [p- | |

| Age (HR per 1 year) | 0.98 (0.97,0.99) | [0.005] |

| Gender: | ||

| Males (n=378) | 1.0 (ref) | [0.091] |

| Females (n=70) | 1.36 (0.95, 1.94) | |

| Entry BE length (per cm) | 0.92 (0.87, 0.97) | [0.003] |

| Entry BE Histology: | ||

| IM/ND (n=63) | 1.0 (ref) | [0.98] |

| LGD (n=68) | 0.96 (0.60, 1.54) | |

| HGD (n=268) | 1.00 (0.68, 1.48) | |

| EAC (n=49) | 1.08 (0.61, 1.92) | |

| RFA Device: | ||

| Circumferential | 1.0 (ref) | [0.87] |

| Focal (n=220) | 1.05 (0.64, 1.70) | |

| Both (n=169) | 0.95 (0.60, 1.51) | |

| Pre RFA Treatment: | ||

| None (n=196) | 1.0 (ref) | [0.44] |

| APC/MPC (n=2) | 0.45 (0.06, 3.31) | |

| EMR (n=245) | 1.34 (0.97, 1.84) | |

| PDT (n=3) | 1.07 (0.25, 4.48) | |

| Cryo (n=2) | 2.72 (0.37, 19.9) | |

Abbreviations: HR=Hazard Ratios; BE=Barrett’s Esophagus; IM/ND = Non Dysplastic; LGD = Low Grade Dysplasia; HGD = High Grade Dysplasia; EAC = Esophageal Adenocarcinoma; RFA = Radio Frequency Ablation; APC/MPC = Argon Plasma Coagulation/Multi Polar Coagulation; EMR = Endoscopic Mucosal Resection; PDT = Photo Dynamic Therapy; Cryo = Cryotherapy.

Entry histology correlated with age. Older patients (age >70) were more likely to have EAC compared to the younger cohort. Older patients were more likely to receive endoscopic treatments (such as EMR) prior to RFA. Also, older patients were likely to receive combination RFA treatments (focal and circumferential ablation). However, as shown in table 2, these factors did not influence time to CRIM.

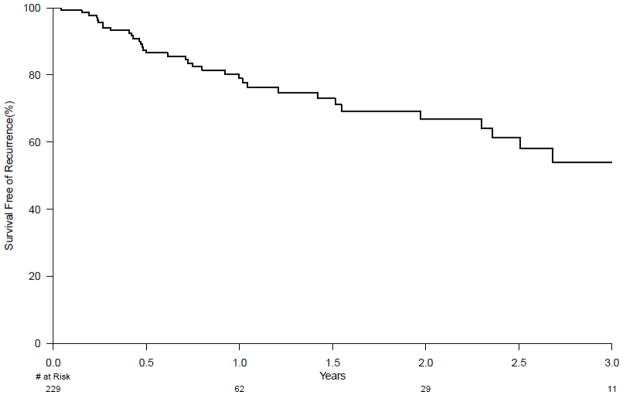

Survival Free of Recurrence

In the 448 patients treated and followed, a total of 229 (51%) patients achieved CRIM. The remaining 219 patients were still undergoing RFA therapy and had not achieved CRIM when the study was closed. As shown on the survival curve (Figure 2), the incidence of recurrence by 1 year was 20% and 33% by 2 years. By three years, recurrences continued to occur but precise estimates were difficult to establish, due to the small number of at-risk subjects (n=11), which made estimates of recurrence less precise i.e. wider confidence intervals. The median duration (range) of follow-up at time of study closure in those without recurrence was 3 months (0 days – 4.6 yrs). No endoscopic or patient factors were associated with time to recurrence on univariate and multivariate analyses (Table 3a,3b,3c). The most common type of recurrent histology was IM without dysplasia in 78% of subjects with recurrence. The remaining 22% were comprised of dysplastic BE (11% HGD, 8% LGD, 3% cancer). None of the patients were found to have sub-squamous IM except one patient who developed sub-squamous carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier curve depicting the durability of complete remission of intestinal metaplasia (CRIM) over 3 years. All subjects with CRIM were analyzed from time 0 and followed forward until recurrence (either intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia) developed or to end of study. At one year, 20% of patients with CRIM had developed recurrence. At two years, 33% of patients had developed recurrence.

Table 3a.

Predictors of Recurrence in tubular esophagus or GEJ: Multiple Variable Regression Models (N=229)

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 (0.96,1.03) | 0.86 |

| Gender (Males relative to Females) | 1.10 (0.44,2.74) | 0.85 |

| EMR prior to RFA (relative to no EMR) | 1.18 (0.60,2.34) | 0.62* |

| Entry BE length (cm) | 1.08 (0.97,1.20) | 0.16* |

| Entry BE Histology (relative to ND) | 0.45* | |

| LGD | 0.66 (0.25,1.76) | |

| HGD | 0.53 (0.23,1.19) | |

| EAC | 0.52 (0.14, 1.91) |

models adjusted for age and gender

Abbreviations: BE=Barrett’s Esophagus; ND= no dysplasia; LGD = Low Grade Dysplasia; HGD = High Grade Dysplasia; EAC = Esophageal Adenocarcinoma; RFA = Radio Frequency Ablation.

Table 3b.

Predictors of Recurrence in tubular esophagus only: Multiple Variable Regression Models (N=229)

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 (0.98,1.06) | 0.42 |

| Gender (Males relative to Females) | 1.63 (0.45,10.45) | 0.49 |

| EMR prior to RFA (relative to no EMR) | 1.40 (0.51,3.88) | 0.51 |

| Entry BE length (cm) | 0.92 (0.82,1.05) | 0.21 |

| Entry BE Histology (relative to ND) | 0.51 | |

| LGD | 0.95 (0.23,6.49) | |

| HGD | 0.78 (0.09,5.16) | |

| EAC | 0.74 (0.21, 3.47) |

Table 3c.

Predictors of Recurrence in GEJ only : Multiple Variable Regression Models (N=229)

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.97 (0.93,1.03) | 0.70 |

| Gender (Males relative to Females) | 2.01 (0.63,5.84) | 0.90 |

| EMR prior to RFA (relative to no EMR) | 2.20 (0.77,6.74) | 0.51 |

| Entry BE length (cm) | 2.46 (0.20,4.48) | 0.50 |

| Entry BE Histology (relative to ND) | 0.32 | |

| LGD | 0.43 (0.13,1.74) | |

| HGD | 0.59 (0.14,2.41) | |

| EAC | 0.45 (0.02, 2.57) |

Location, Histology and Management of Recurrences

Of the 37 patients (16% of subjects achieving CRIM) with recurrence, 18 patients had recurrences exclusively in the original esophageal segment, two patients had recurrences within the esophageal body and GEJ, and the remaining 17 patients had recurrences at the GEJ only. A total of 8 patients had dysplastic recurrences and 29 patients had IM only, without dysplasia.. The most common location for dysplastic recurrence was the GEJ, with 5 of 8 patients having dysplasia at the GEJ. One out of 37 patients (3% of all recurrences) had worse histology of recurrence (sub-squamous cancer) compared to entry histology (HGD).

A. Esophageal body

Of the 18 recurrences, 85% (15 patients) developed IM and 15% (3 patients) developed dysplastic BE. One patient developed LGD, the second HGD and the third developed subsquamous esophageal cancer. This is the only cancer that developed in all 37 patients. The entry histology of the 15 patients that recurred with IM was HGD (7 patients), LGD (2 patients) and NDBE (6 patients). The three patients with recurrent dysplastic BE had HGD on entry histology. All three patients were responsive to therapy. The patient with HGD recurrence responded to EMR. The patient with LGD received APC plus focal RFA. The third patient had subsquamous T1b cancer with lymphovascular invasion requiring an esophagectomy within 4 months of CRIM. The final surgical pathology revealed negative margins and no evidence of lymph node involvement (18 lymph nodes were resected). Seven months after surgery, the patient remains cancer free. The average length of recurrent BE was 1.2 cm.

B. GEJ and esophageal body

For the two recurrences at the GEJ and esophageal body, one patient recurred with IM and one with LGD. Both patients had HGD as entry histology. The patient with LGD developed an esophageal stricture after RFA therapy to treat recurrent LGD. Due to this he was subsequently treated with cryotherapy and APC to eliminate all IM, which was successful. The patient with IM was not treated and did not progress in disease status. At the time of diagnosis of recurrence, both patients had a normal appearing neo-squamocolumnar junction but abnormal columnar mucosa in the tubular esophagus. The average length of recurrent BE was 2cm.

C. GEJ

Of the 17 recurrences at the GEJ, 72% (13 patients) recurrences were IM and 28% (4 patients) were dysplastic BE (three patients had HGD, and one had LGD). On entry histology, all four patients had HGD. None of the recurrences had worse dysplasia grade when compared to entry histology. For those with IM recurrence (13 patients), 6 patients on entry histology had HGD, 5 patients had LGD and 2 patients had NDBE. Comparing histologic to endoscopic findings, 8 patients had a normal appearing neo-squamocolumnar junction with the remaining showing visible abnormalities evident on white light or narrow band imaging. The average length of recurrent BE detected was less than 0.5cm.

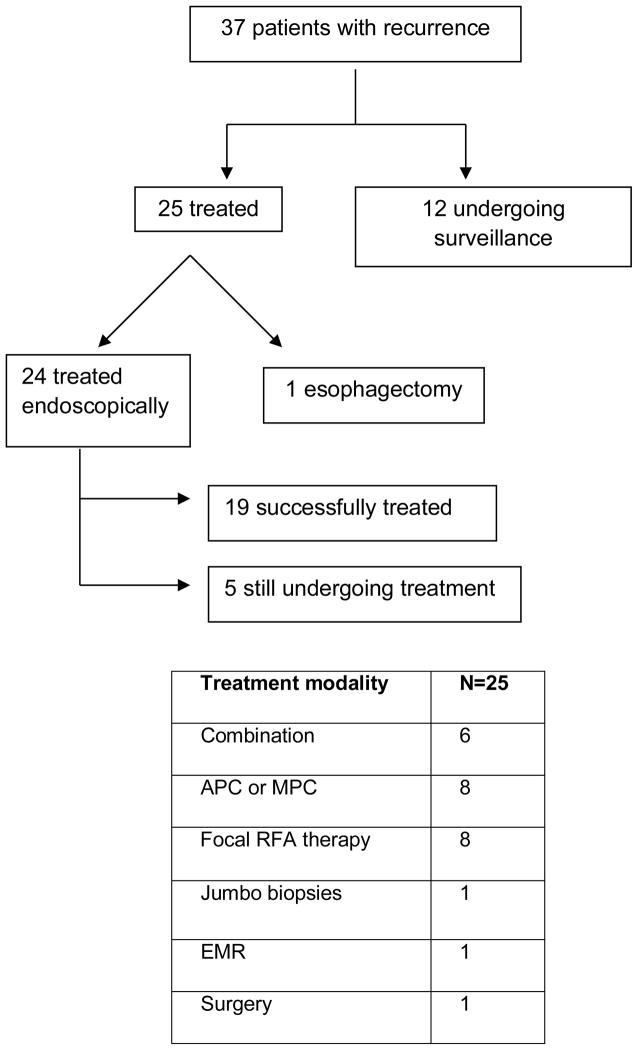

Management

A total of 25 patients received endoscopic or surgical management of their recurrence, and 12 patients received endoscopic surveillance only (Figure 3). Only one of the 25 patients underwent esophagectomy for T1b adenocarcinoma. Details are provided in Figure 3. For the patients that were under surveillance, one patient had LGD and the remaining 11 patients had IM. After a mean follow up of 3.4 months, none of the patients had progressed in their dysplasia grade.

Figure 3.

Summary and The Endoscopic Treatments of Recurrent BE (N=37). APC = Argon Plasma Coagulation; MPC = Multi Polar Coagulation; RFA= Radio Frequency Ablation; EMR = Endoscopic Mucosal Resection

Safety and Adverse events

Of the 592 patients treated with a minimum one dose of RFA, 39 patients had adverse events (6.5%). The most common adverse event was stricture formation (27 patients) followed by bleeding (8), mucosal tears (2) and hospitalizations for dysrhythmias (2). There were no blood transfusions, perforations or surgical interventions required. All patients with strictures were easily dilated endoscopically. Increasing BE length was associated with an increased development of complications [OR 1.10, (95% CI 1.01, 1.21)], and a trend towards increased risk of strictures [(1.08 (0.97, 1.20)] (Table 4). Use of EMR prior to RFA showed a trend towards significance as a risk factor for complications (p=0.06). Gender, age, and entry histology were not predictive of complications.

Table 4.

Predictors of Complications and Stricture formation: Multivariable Regression Models (N=37).

| Complications | Stricture Formation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Age | 1.03 (0.99,1.07) | 0.06 | 1.03 (0.99,1.08) | 0.09 |

| Gender: | ||||

| Female | 1.0 (ref) | 0.61 | 1.0 (ref) | 0.51 |

| Male | 1.29 (0.50,3.42) | 1.53 (0.45,5.22) | ||

| BE length (cm) | 1.10 (1.03,1.24) | 0.03* | 1.08 (0.97,1.20) | 0.18 * |

| Prior EMR: | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref) | 0.06* | 1.0 (ref) | 0.30 * |

| Yes | 2.07 (0.99,4.29) | 1.55 (0.65,3.56) | ||

| Entry BE Histology | ||||

| IM ND | 1.0 (ref) | 0.80* | 1.0 (ref) | 0.80 * |

| LGD | 1.80 (0.46,7.28) | 0.72 (0.14,3.77) | ||

| HGD | 1.52 (0.44,5.26) | 1.02 (0.29,3.64) | ||

| EAC | 1.93(0.46,8.18) | 1.57 (0.35,6.99) | ||

model adjusted for age and gender

Abbreviations: BE=Barrett’s Esophagus; ND= no dysplasia; LGD = Low Grade Dysplasia; HGD = High Grade Dysplasia; EAC = Esophageal Adenocarcinoma; RFA = Radio Frequency Ablation.

DISCUSSION

The goal of endoscopic ablation treatment in BE is to achieve complete remission of intestinal metaplasia (CRIM) and dysplasia with long term maintenance of this status, reducing cancer risk18 while incurring minimal complications. To date, there is little data on the ability to achieve and maintain CRIM in HGD/EAC patients treated endoscopically in unselected patients referred to large tertiary referral centers. To our knowledge, our study is the largest series of dysplastic BE patients treated at multiple expert centers, described in the literature to date. Patients of younger age with shorter lengths of BE were more likely to achieve CRIM. However, a substantial proportion (33% at 2 years following CRIM) of these patients developed recurrent BE. We were unable to identify any patient/endoscopic characteristics that were predictive of recurrence. A relatively small percentage (6.5%) of all patients treated with RFA developed any adverse events, and none were life threatening.

The rate of CRIM in our large cohort study is lower compared to recently published studies3–6, 8–12. However, there are other studies that have treated dysplastic BE and shown CRIM ranging from 43–65%19–21. In a multicenter US registry19, 142 HGD patients received circumferential RFA and 54% achieved CRIM in 12 months. In a single center prospective study20, 63 patients with LGD or HGD were treated with circumferential RFA and 67% achieved CRIM after 21 months. Recently, in a retrospective case review, 90 patients with dysplastic BE received EMR and RFA, but only 43% achieved CRIM after 20 months21. The lower rate of CRIM in our study is likely due to the inclusion of GEJ, a region that has not been treated and followed in studies with higher CRIM rates. In addition, studies reporting higher CRIM had smaller sample size and treated shorter lengths of BE than our current study. The mean length of BE across studies have been similar. However, in this study, 15% of patients had a BE length over 8 cm. In comparison, the AIM dysplasia trial did not recruit BE length over 8 cm. We found age and initial BE length to be predictors of CRIM. This has been shown on univariate analysis in other studies10, 11, but not in multivariate analysis to date. Longer segments of BE have been associated with a higher risk of progression22, and potentially aggressive BE biology23. At this time it is unclear how age contributes to the extent of severe biology of BE, but it is a well-recognized predictor of progression to EAC23. We found age to be associated with BE histology, with older patients being more likely to have higher grades of dysplasia than younger patients. The geriatric literature reports that physiologic changes increase after the age of 75 24, 25. These changes may reflect the accumulation of cellular aberrations with advancing age. We also found that older patients received more pre-RFA treatments (EMR) and combination RFA therapy to eradicate BE. However, these factors did not affect the achievement of CRIM. The rates of CRIM achieved with RFA were also unaffected by endoscopic treatments (predominantly EMR) applied prior to RFA.

Our recurrence rate of 33% at two years is higher than previously reported in similar size studies. It is possible that with the short median follow up of patients without recurrence (3 months), our reported rate may be an underestimate. Recurrence rates post-ablation in the literature range from 5–31%2–6, 8–10. Follow up data on the AIM dysplasia trial11 showed 17% recurrence of IM and 15% recurrence of dysplasia after two years of follow up. These numbers are in keeping with majority of the literature published to date, and are the current benchmark utilized. However, higher rates have recently been published by Vacarro et al, where a single center study of 47 patients followed for 13 months10 had a recurrence rate of 26%. One of the potential reasons for variability in the rates of recurrence is the inclusion of the GEJ in the biopsy protocol. The AIM dysplasia trials11, 12 did not obtain biopsies from GEJ post-RFA, but rather from the region proximal to the neo-squamocolumnar junction and the GEJ. While assessment of the GEJ is challenging due to difficulty in identification of landmarks, this area is routinely treated at the time of ablation. There is also emerging evidence that the progenitor cells for BE may be located in the gastric cardia 26. While the status of the GEJ in terms of presence or absence of intestinal metaplasia was not known before ablation, CRIM was defined as the absence of intestinal metaplasia at the GEJ and the tubular esophagus in two successive surveillance endoscopies. The presence of recurrent BE at both locations suggests potential incomplete eradication with RFA. Sampling error due to varying biopsy protocols is an alternate possibility. However, we believe this is less likely given the stringent criteria we used to define CRIM (2 successive endoscopies showing no IM in the esophagus and GEJ). We also identified a higher incidence of dysplastic recurrence in the GEJ, similar to Vacarro et al10. This suggests a higher potential for severe disease to recur at the GEJ, despite achieving CRIM. It may possibly reflect ongoing damage from GERD with associated progression to metaplasia and neoplasia. Conversely, it could represent incomplete eradication of IM by RFA. Recurrence of IM and neoplasia of the GEJ have been reported in studies following successful EMR and APC treatment27. Thus, the importance of careful surveillance of the esophagus and the GEJ following ablation cannot be overstated.

In this study, we have shown that recurrent IM can be managed endoscopically. In our cohort, a wide variety of modalities were used to re-achieve CRIM. However, durability of re-achieved CRIM is not known. An alternative management of these cases is surveillance only. More data on the natural history of recurrent IM without dysplasia, particularly at the GEJ, needs to be obtained before definitive therapeutic recommendations can be made. Given the absence of formal guidelines for the management of recurrent IM, especially non dysplastic IM at the GEJ, after successful RFA, the different approaches to the management of these patients likely reflects practice variation at the three participating centers. We were unable to identify any endoscopic or demographic predictors of recurrent IM following successful ablation.

In this study, 6.5% of all patients treated with RFA (N=592) developed a complication, and 4% of all patients developed strictures. This is comparable to a recently published review of 15 RFA studies where a <5% overall complication rate and 2.2% stricture formation rate was reported28. We had a slightly higher overall complication rate likely due to the substantial number of patients receiving pre RFA therapy. 55% of patients received EMR, and a small proportion received cryotherapy, PDT or APC/MPC. When our results are compared to combination RFA therapy studies, such as EMR + RFA, our rates are lower21, 25. The Pouw et al study25 recruited 24 patients with HGD, LGD or ND BE. After 22 months, 29% of all patients developed some complication, of which 21% were strictures. In the Okoro et al study21, 44 patients with HGD, LGD or ND BE were studied for complications. After 20 months, 14% developed strictures. Our complication rates are lower than those reported for PDT (40%) and EMR alone (20%). In view of these findings, RFA remains a relatively safe and well-tolerated treatment option. We did not collect data on chest pain or dysphagia, as this study was geared towards the more serious complications. We identified entry BE length as a predictor of overall complications, which is biologically plausible as length is directly associated with the number of treatments applied and the achievement of CRIM. Thus, those patients with a longer time to achieve CRIM may be at a higher risk of complications.

The strengths of this study include the large number of patients studied, which is the largest number of subjects with dysplastic BE (particularly HGD and intramucosal EAC) treated with RFA to date. The multicenter nature of this report further strengthens the validity of our findings and potentially its generalizability to other practices which treat a large number of subjects with BE related dysplasia. The high proportion of subjects treated with EMR before RFA reflects current recommendations on the management of patients with HGD and IMCa. Recently an abstract of the United States BE Registry released their results of CRIM and recurrence29. However, HGD and EAC were represented in only 26% of the population (versus 71% in our study). Unlike previously reported studies7, 11, patients in our study received multiple types of endoscopic therapies prior to RFA, particularly EMR. There was no restriction on the frequency and type of modality utilized. Thus, our results are a reflection of the way dysplastic BE patients are currently being managed in clinical practice.

14% of the subjects treated in this study had NDBE before ablation, which is not a routinely accepted indication for RFA. However, ablation of non-dysplastic BE in high risk subjects (such as those with a family history of adenocarcinoma, long segment: greater than 6–10 cm) has been proposed2. Many (64%) of these non- dysplastic BE patients included in this study fall into these categories. Of the 77 subjects with no dysplasia who underwent RFA, 19 (25%) had BE segments equal to or greater than 6 cm in length, 18 (24%) were treated as part of a clinical trial, 8 (10%) had a family history of BE or esophageal adenocarcinoma, 3 were less than 30 years of age with long segment BE and 1 had a prior history of esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma. Pre-ablation histology did not predict outcomes studied in this manuscript: CRIM, recurrence or complications. Sampling error is a concern when recurrence is considered. We tried to overcome this by defining CRIM more conservatively, where patients had to have two negative endoscopies and histology clear of IM. In addition, only one patient had subsquamous cancer, and none had documented subsquamous BE. This could be attributed to the limitation in the depth of biopsy obtained, which has been recently studied and quoted to be adequate in only 30% of biopsies taken post ablation30. Finally, these were all patients referred to tertiary centers and may not be representative of the results in community practices.

The findings of this study emphasize the importance of careful endoscopic surveillance following successful ablation of BE subjects with RFA. Despite ability of RFA to achieve CRIM, recurrence of IM and dysplasia appears to occur in a substantial proportion of subjects (33% at 2 years). While dysplastic recurrences are more often diagnosed within the GEJ, recurrences were just as frequent in the original esophageal segment. Until predictive biomarkers are identified and available for clinical practice, endoscopic surveillance directed at the GEJ and original BE segment should be continued. It is currently the practice to survey these patients intensely after CRIM is achieved at 3–6 month intervals, depending on the initial histology of the lesion. If no recurrence is found, surveillance is generally decreased to 6–12 month intervals.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: PGI, JAA, GWF, GGG, KKW, AKR and TCW receive support from the NIH Grant 1U54CA163004-01 for this study

Abbreviations

- APC

Argon Plasma Coagulation

- BE

Barrett’s Esophagus

- BETRNet

Barrett’s Esophagus Translational Research Network

- CRD

Complete Remission of Dysplasia

- CRIM

Complete Remission of Intestinal Metaplasia

- EAC

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

- EMR

Endoscopic Mucosal Resection

- EUS

Endoscopic Ultrasound

- GEJ

Gastroesophageal Junction

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- HGD

High Grade Dysplasia

- IM

Intestinal Metaplasia

- IQR

Interquartile Range

- LGD

Low Grade Dysplasia

- MPC

Multipolar Coagulation

- NBI

Narrow Band Imaging

- PDT

Photodynamic Therapy

- RFA

Radiofrequency Ablation

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Milli Gupta, MD, FRCP(C): none to declare

Prasad G. Iyer MD, MS: Research Funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals

Lori Lutzke, CCRP: None to declare

Emmanuel C. Gorospe, MD, MPH: none to declare

Julian A. Abrams, MD, MS : none to declare

Gary W. Falk, MD, MS: none to declare

Gregory G. Ginsberg, MD: none to declare

Anil K. Rustgi, MD: none to declare

Charles J. Lightdale, MD: none to declare

Timothy C. Wang, MD: none to declare

John M. Poneros, MD: none to declare

David I. Fudman, MD: none to declare

Kenneth K. Wang, MD: Research support from BaRRx, Pinnacle Pharma, CSA

Author contributions:

Milli Gupta, MD, FRCP(C): study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis

Prasad G. Iyer MD, MS: Study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; technical and material support

Lori Lutzke, CCRP: acquisition of data

Emmanuel C. Gorospe, MD, MPH: analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Julian A. Abrams, MD, MS: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Gary W. Falk, MD, MS: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; technical and material support.

Gregory G. Ginsberg, MD: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; technical and material support.

Anil K. Rustgi, MD: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; technical and material support.

Charles J. Lightdale, MD: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; technical and material support. Timothy C. Wang, MD: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; technical and material support. John M. Poneros, MD: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

David I. Fudman, MD: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Kenneth K. Wang, MD: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; obtained funding; technical and material support; study supervision.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pohl H, Welch HG. The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:142–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1084–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gondrie JJ, Pouw RE, Sondermeijer CM, et al. Effective treatment of early Barrett’s neoplasia with stepwise circumferential and focal ablation using the HALO system. Endoscopy. 2008;40:370–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gondrie JJ, Pouw RE, Sondermeijer CM, et al. Stepwise circumferential and focal ablation of Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia: results of the first prospective series of 11 patients. Endoscopy. 2008;40:359–69. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pouw RE, Gondrie JJ, Sondermeijer CM, et al. Eradication of Barrett esophagus with early neoplasia by radiofrequency ablation, with or without endoscopic resection. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2008;12:1627–36. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0629-1. discussion 1636–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pouw RE, Wirths K, Eisendrath P, Sondermeijer CM, et al. Efficacy of radiofrequency ablation combined with endoscopic resection for barrett’s esophagus with early neoplasia. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2010;8:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischer DE, Overholt BF, Sharma VK, et al. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s esophagus: 5-year outcomes from a prospective multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2010;42:781–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrero LA, van Vilsteren FG, Pouw RE, et al. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation combined with endoscopic resection for early neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus longer than 10 cm. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011;73:682–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Vilsteren FG, Pouw RE, Seewald S, et al. Stepwise radical endoscopic resection versus radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s oesophagus with high-grade dysplasia or early cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Gut. 2011;60:765–73. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.229310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaccaro BJ, Gonzalez S, Poneros JM, et al. Detection of intestinal metaplasia after successful eradication of Barrett’s Esophagus with radiofrequency ablation. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2011;56:1996–2000. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1680-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaheen NJ, Overholt BF, Sampliner RE, et al. Durability of radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:460–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360:2277–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inadomi JM, Somsouk M, Madanick RD, et al. A cost-utility analysis of ablative therapy for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2101–2114. e1–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hur C, Choi SE, Rubenstein JH, et al. The Cost Effectiveness of Radiofrequency Ablation for Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2012 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue H, Takeshita K, Hori H, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection with a cap–fitted panendoscope for esophagus, stomach, and colon mucosal lesions. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 1993;39:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soehendra N, Binmoeller KF, Bohnacker S, et al. Endoscopic snare mucosectomy in the esophagus without any additional equipment: a simple technique for resection of flat early cancer. Endoscopy. 1997;29:380–3. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine DS, Haggitt RC, Blount PL, et al. An endoscopic biopsy protocol can differentiate high-grade dysplasia from early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:40–50. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2008;103:788–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganz RA, Overholt BF, Sharma VK, et al. Circumferential ablation of Barrett’s esophagus that contains high-grade dysplasia: a U.S. Multicenter Registry. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2008;68:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma VK, Jae Kim H, Das A, et al. Circumferential and focal ablation of Barrett’s esophagus containing dysplasia. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2009;104:310–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okoro NI, Tomizawa Y, Dunagan KT, et al. Safety of prior endoscopic mucosal resection in patients receiving radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2012;10:150–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wani S, Falk G, Hall M, Gaddam S, et al. Patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus have low risks for developing dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2011;9:220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.008. quiz e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasad GA, Bansal A, Sharma P, et al. Predictors of progression in Barrett’s esophagus: current knowledge and future directions. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2010;105:1490–1502. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onafowokan A, Mulley GP. Age-related geriatric medicine or integrated medical care? Age and ageing. 1999;28:245–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grabowski J, Pintus D, Ramesh H, et al. The challenges of treating cancer in older patients - How effective are clinical trials in developing unique treatments? European Oncology. 2008;4:94–96. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quante M, Bhagat G, Abrams JA, et al. Bile acid and inflammation activate gastric cardia stem cells in a mouse model of Barrett-like metaplasia. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pouw RE, Seewald S, Gondrie JJ, et al. Stepwise radical endoscopic resection for eradication of Barrett’s oesophagus with early neoplasia in a cohort of 169 patients. Gut. 2010;59:1169–77. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.210229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bulsiewicz WJ, Shaheen NJ. The role of radiofrequency ablation in the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointestinal endoscopy clinics of North America. 2011;21:95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaheen NJ, Bulsiewicz WJ, Rothstein RI, et al. Eradication Rates of Barrett’s Esophagus Using Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA): Results From the US RFA Registry. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2012;75:460–460. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta N, Mathur SC, Dumot JA, et al. Adequacy of esophageal squamous mucosa specimens obtained during endoscopy: are standard biopsies sufficient for postablation surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2012;75:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]