Abstract

The goal was to identify factors that predicted sustained cocaine abstinence and transitions from cocaine use to abstinence over 24 months. Data from baseline assessments and multiple follow-ups were obtained from three studies of continuing care for patients in intensive outpatient programs (IOPs). In the combined sample, remaining cocaine abstinent and transitioning into abstinence at the next follow-up were predicted by older age, less education, and less cocaine and alcohol use at baseline, and by higher self-efficacy, commitment to abstinence, better social support, lower depression, and lower scores on other problem severity measures assessed during the follow-up. In addition, higher self-help participation, self-help beliefs, readiness to change, and coping assessed during the follow-up predicted transitions from cocaine use to abstinence. These results were stable over 24 months. Commitment to abstinence, self-help behaviors and beliefs, and self-efficacy contributing independently to the prediction of cocaine use transitions. Implications for treatment are discussed.

Keywords: cocaine dependence, cocaine abstinence, recovery, predictors, treatment response, follow-up, treatment

1. Introduction

Individuals with cocaine dependence are widely seen as difficult to successfully treat and particularly prone to relapse. However, there clearly are individuals with histories of severe cocaine addiction who manage to achieve stable and long-lasting periods of abstinence from the drug (Carroll, Power, Bryant, & Rounsaville, 1993; Hser et al., 2006; McKay & Weiss, 2001; Simpson, Joe, Fletcher, Hubbard, & Anglin, 1999). These success stories raise important questions about how long-lasting abstinence from cocaine is achieved.

Much of the research in this area has focused on baseline predictors of cocaine outcomes during relatively short treatments. Patients who report current cocaine use or produce a cocaine positive urine sample are much more likely to drop out of treatment or have poorer short-term cocaine use outcomes than those who are not using cocaine at that point (Ahmadi et al., 2009; Alterman et al., 1997; Kampman et al., 2002; Reiber, Ramirez, Parent, & Rawson, 2002). Other baseline predictors of poorer cocaine use treatment outcomes have included prior drug treatments, younger age, comorbid depression, lower commitment to change, cocaine craving, lower confidence in being able to avoid cocaine use in high-risk situations, cognitive deficits, and presence of a co-occurring alcohol use disorder (Aharonovich, Amrhein, Bisaga, Nunes, & Hasin, 2008; Aharonovich et al., 2006; Carroll et al., 1993; Dennis, Scott, Funk, & Foss, 2005; Hser, Joshi, Anglin, & Fletcher, 1999; Hser et al., 2006; Poling, Kosten, & Sofuoglu, 2007; Rohsenow, Martin, Eaton, & Monti, 2007; Schmitz et al., 2009; Simpson, Joe, & Broome, 2002; Siqueland et al., 2002; Stulz, Thase, Gallop, & Crits-Christoph, 2011).

Fewer studies have looked to identify predictors of longer-term outcomes in cocaine dependent patients. Not surprisingly, several studies have found that better retention in treatment predicts better outcomes (McKay & Weiss, 2001; Reiber, et al., 2003; Siqueland et al., 2002; Simpson et al., 2002), as does participation in subsequent treatment episodes (Hser, Evans, Huang, Brecht, & Li, 2008). In addition, better cocaine use outcomes early in treatment strongly predict better longer-term outcomes (Havassy, Wasserman, & Hall, 1995; Higgins, Badger, & Budney, 2000; McKay et al., 1999; McKay et al., under review; Reiber et al., 2002).

Greater participation in self-help programs during follow-up has generally predicted better cocaine use outcomes (Hser et al., 2008; Kissin, McLeod, & McKay, 2003; McKay et al., 1997; McKay, Merikle, Mulvaney, Weiss, & Koppenhaver, 2001), but not in all studies (McKay et al., 2005a). Higher self-efficacy, commitment to abstinence, and positive mood assessed during follow-up have predicted better subsequent cocaine use outcomes in several studies (Hall, Havassy, & Wasserman, 1991; McKay et al., 1997; McKay et al., 2001), whereas continued depression (Stulz et al., 2011) and craving (Weiss et al., 2003) have predicted cocaine relapse. In a study with a 12 year follow-up, cocaine dependent patients who achieved 5 or more years of continuous cocaine abstinence had lower rates of depression and psychotic disorders, fewer psychiatric symptoms, less criminal involvement, and lower unemployment than those who had not achieved stable abstinence (Herbeck et al., 2006; Hser et al., 2006). Finally, greater social integration and more perceived social support assessed shortly after the end of treatment predicted better cocaine use outcomes for Caucasian, but not African-American participants in a study by Havassy, Wasserman, and Hall (1995).

Considerably more work has been done to determine predictors of longer-term outcomes from alcohol treatment. While it is beyond the scope of this article to provide a comprehensive review of this literature, a few studies will be highlighted. Low readiness to change, low self-efficacy, poor coping behaviors, greater craving, and lack of participation in self-help programs have consistently been associated with poor drinking outcomes (Connors, Maisto, & Zywiak, 1996; Miller, Westerberg, Harris, & Tonigan, 1996; Moos, Finney, & Cronkite, 1990; Moos & Moos, 2004 Project MATCH Research Group, 1998; Tonigan et al., 1996). Moreover, poorer alcohol use outcomes have been predicted by interpersonal problems and lack of social support for abstinence (Longabaugh, Wirtz, Beattie, Noel, & Stout, 1995; Moos et al., 1990; Weisner, Delucchi, Matzger, & Schmidt, 2003). For example, Moos et al. (1990) found that more problematic family environments, particularly those characterized by low cohesion, and greater life stress assessed at a two-year follow-up were associated with worse drinking outcomes at that point, and were even more strongly associated with drinking outcome 8 years later.

Recent work by Witkiewitz has made use of newer statistical procedures to examine dynamic relations between risk factors and alcohol use outcomes. For example, one study (Witkiewitz, 2011) found that alcohol use outcomes over a 12 month period after treatment were predicted by negative mood, craving, perceived stress, and self-efficacy assessed over time, and that these factors were also predicted by prior drinking in the follow-up. Mediation analyses that included baseline factors indicated that individuals with greater psychiatric symptoms and more prior treatments were at greater risk for heavy drinking if they had an increase in risk factors during the follow-up. In a second study, better coping skills assessed at post treatment follow-ups were related to less severe first lapses and lighter drinking subsequent to the first lapse (Witkiewitz & Masyn, 2008).

One important clinical issue with regard to long-term recovery that has received relatively little attention in addiction treatment research is the factors that predict transitions between periods of abstinence and use during follow-ups. In one study, transition from substance use to abstinence status during follow-up was predicted by fewer symptoms of mental distress, fewer legal problems, more non-using friends, and more time in treatment (Scott, Foss, & Dennis, 2005). There is also some evidence that in cocaine dependent patients, men transition more rapidly between these two states than women (Gallop et al., 2007). With regard to alcohol use, a latent transition analysis using data from Project MATCH found a dynamic relation between negative affect and drinking, such that changes in drinking status were associated with prior changes in negative affect, and that changes in negative affect were related to prior changes in drinking (Witkiewitz & Villarroel, 2009).

The goal of this article is to identify factors that are associated with sustained cocaine abstinence and transitions from non-abstinence to abstinence in cocaine dependent patients. The data used in the analyses were from three studies of continuing care with 24-month follow-ups (McKay et al., 2005; McKay et al., 2010; McKay et al., under review), which yielded a combined sample size of 766. Participants were categorized as cocaine abstinent or non-abstinent for each follow-up period across the 24 month follow-ups. Analyses examined baseline predictors of transitions between cocaine use states during the follow-up. Lagged analyses were also conducted with variables assessed at each follow-up, to determine which variables predicted transitions from one follow-up period to the next. The inclusion of time main effects and interactions allowed for the determination of whether predictor effects were stable across the 24 month follow-ups, or changed over time.

Selection of predictor variables was guided by findings from previous studies cocaine and alcohol use outcomes following treatment. Variables were selected to measure constructs associated with four factors that have consistently predicted substance use outcomes and have figured prominently in theoretical models that have sought to explain treatment outcome and relapse (Dennis & Scott, 2007; Folkman, Lazarus, Kunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986; Humphreys, 2004; Kaplan, 1996; Moos et al., 1990; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004): Self/mutual-help (e.g., commitment to abstinence, self-help participation, self-help beliefs), cognitive-behavioral and transtheoretical models of change (e.g., self-efficacy, coping, and readiness to change), social support (e.g., social support for recovery, general social support, family problem severity), and other stressors (e.g., psychiatric, medical, employment, legal problem severities).

Based on prior research, younger patients and those with more prior treatments and greater substance use at baseline were predicted to be less likely to remain cocaine abstinent or to transition into cocaine abstinence from one period to the next across the follow-up. With regard to time-varying variables, higher scores on variables assessing positive factors (e.g., self-efficacy, self-help participation, etc.) were hypothesized to predict continued cocaine abstinence and transitions into cocaine abstinence, whereas high scores on variables assessing negative factors (e.g., depression, social support for continued substance use, etc.) were hypothesized to predict a decreased probability of cocaine abstinence. The analyses also explored whether the effects of the variables on transitions in cocaine use status from one follow-up period to the next were moderated by whether the participants were in a cocaine abstinent or using state at the earlier point. Finally, analyses were also done to determine which variables made independent contributions to the prediction of transitions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants in Study 1 (N=268) were patients from either the Philadelphia VA IOP or a publicly funded IOP. Participants from Studies 2 (N=177) and 3 (N=321) were patients in two publicly funded IOPs. Participants in Studies 1 and 2 all met criteria for current DSM-IV cocaine dependence at the time of entrance to treatment. Those in Sample 3 met lifetime criteria for cocaine dependence and were using cocaine in the six months prior to entrance to treatment. Participants in Study 1 had completed their IOPs, which were both 4 weeks in duration. Participants in Studies 2 and 3 had completed 3 weeks and 2 weeks, respectively, of their IOPs, which both featured flexible lengths of stay that could extend up to 3-4 months.

The other criteria for eligibility in each study were a willingness to participate in research and be randomly assigned to one of the three continuing care conditions in each study; no psychiatric or medical condition that precluded outpatient treatment; between the ages of 18 and 65; no IV heroin use within the past 12 months; ability to read at approximately the 4th grade level; and at least a minimum degree of stability in living situation. To facilitate follow-up, participants had to be able to provide the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of at least two contacts. The participants in each study were on average in their early 40s, and approximately 70% were male and 85% African American. They averaged around 12 years of regular cocaine use and four prior treatments for drug problems.

The three studies were similar in many respects. Each study sample consisted primarily of African-American men, who were in treatment in urban, publicly-funded intensive outpatient programs (IOPs), and were recruited after 2-4 weeks of IOP participation. Participants were enrolled between 3/1997 and 8/2000 in Study 1, 5/2004 and 8/2007 in Study 2, and 6/2007 and 2/2009 in Study 3. Participants in each study were randomly assigned to three continuing care conditions, which were treatment as usual and various types of telephone continuing care in all three studies, and CBT continuing care in one study.

2.2. Intensive Outpatient Program

Treatment was focused on overcoming denial, fostering participation in self-help groups, and providing information about the process of addiction and cues to relapse (McKay et al., 1994; McKay et al., 2010). These programs provided approximately 9 hours of group-based treatment per week.

2.3. Continuing Care Treatment Conditions

In all three studies, participants were randomly assigned to either treatment as usual (TAU) in the program or two other continuing care conditions [Study1: CBT/RP and telephone continuing care; Study 2: extended telephone monitoring only and extended telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC); Study 3: TMC and TMC plus incentives for attendance]. Complete information about the continuing care conditions, the counselors who delivered them, and procedures to monitor adherence to treatment protocols are presented elsewhere (McKay et al., 2004; McKay et al., 2010; Van Horn et al., 2011).

2.4. Procedures

Potential participants were screened at some point during their first two weeks of treatment by research technicians. Informed consent procedures were completed for those who appeared eligible after completing the duration of IOP required in each study. A final determination of eligibility for the study was made during the baseline assessment. The follow-up assessments were conducted at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months post baseline in Studies 1 and 3, and also at 15 and 21 months in Study 2. Participants received $35-50 for completing the baseline research sessions, and $35-50 per visit for completing each the follow-up sessions. All study interviews were conducted by research personnel who had received extensive training on the assessment instruments and were closely monitored during the course of the study. The follow-up rates in each study ranged from a high of 80% to 95% at 3 months to a low of 74% to 86% at 24 months. Overall, follow-up rates were slightly higher in Study 1 than in Study 2 and 3. All procedures followed were in accordance with the standards of the Committee on Human Experimentation at the University of Pennsylvania.

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Baseline measures

Data on gender, race, age, education, prior treatments for substance use disorders, and days of cocaine and alcohol use at baseline were obtained from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McLellan et al., 1980). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al., 2002) was used to confirm cocaine dependence diagnosis, obtain diagnoses for major depression and PTSD, and rule out any psychiatric disorders that would preclude study participation.

2.5.2. Substance use measures

Urine samples were obtained at baseline and at each follow-up point to serve as the primary measure of cocaine use. The urine samples were tested for the cocaine metabolite benzoylecgonine using either the Emit assay system or FPIA analysis (with quantitative output converted to a dichotomous variable). Time-line follow-back (TLFB) (Sobell et al., 1979) calendar assessment techniques were used to gather self-reports of cocaine and alcohol use during each segment of the 24 month follow-up period. Studies with alcoholics (Sobell et al., 1988) and drug users (Ehrman and Robbins 1994) have demonstrated test-retest reliability of .80 or greater. In validity studies, TLFB reports of percent days abstinent have generally correlated .80 or better with collateral reports (Maisto et al., 1979; Stout et al., 1989).

2.5.3. Time-varying predictor variables

A total of 14 variables that were assessed repeatedly during the study follow-ups were included in the analyses. Six of these variables were available from all three studies, whereas 8 available from 2 of 3 studies (Processes of Change, IPI, and BDI: Studies 2 and 3; and ASI problem severity measures: Studies 1 and 3).

Self-help related variables

Degree of commitment to abstinence was assessed with the Thoughts About Abstinence Scale (Hall et al., 1991) a single-item measure with 6 possible abstinence goals: (a) total abstinence, never use again; (b) total abstinence, but realize a slip is possible; (c) occasional use when urges strongly felt; (d) temporary abstinence (e) controlled use; and (f) no goal. As in prior work (Hall et al., 1991), the abstinence goal was transformed into a dichotomous variable (absolute abstinence=1 vs. all other goals=0).

An 8-item self-report scale was used to assess patients' participation in self-help groups. The scale yields a count of the number of times the participant went to self-help group meetings, performed various functions at the meetings, talked to a sponsor, or called other group members in the prior 30 days. The scale was log transformed prior to analyses, with higher scores indicating greater self-help participation. A second 5-item scale assessed the degree to which the participant endorsed key beliefs of 12 step programs, include powerless over alcohol and drugs, belief in a higher power, belief in concepts of faith and spirituality, and sense of fellowship with others (range from 0-20, with higher scores indicating stronger endorsement of beliefs). The measure has good internal consistency and predictive validity (McKay et al., 1994).

Cognitive-behavioral and transtheoretical variables

The Drug-Taking Confidence Questionnaire (DTCQ) (Annis and Martin, 1985) was used to assess self-efficacy in 8 domains (range of 0 - 100%, indicating degree of confidence in one's ability to cope without using cocaine in that situation). Scores on the 8 subscales were averaged to produce one variable, which has predicted substance use outcomes in prior studies (McKay et al., 1983; McKay et al., 2001). Readiness to change was assessed with the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Questionnaire (URICA; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984). A total score was calculated as the sum of the contemplation, action, and maintenance scores divided by the pre-contemplation score (Project MATCH Research Group, 1997). Coping behaviors were assessed with the Processes of Change scale (Prochaska, Velicer, DiClemente, & Fava, 1988), modified for cocaine use. Participants rated how often they employ various coping behaviors to avoid cocaine use on a scale of 1-5 (never to almost always), with a higher score indicating more frequent use of the coping behavior described in the item. The average item score was used for analysis and presentation.

Social support variables

Information on degree of social support for recovery (i.e., abstinence) was assessed with the Important People Interview (IPI; (Zywiak et al., 2009)). At each assessment point, participants nominate up to 10 people in their social network, and provide information on those people. The variable that was included in the analyses was the number of people who supported or encouraged continued substance use (dichotomized as 0 vs. 1 or more). Perceived social support from family members was assessed with Procidano and Heller's 20-item scale (1983), which inquires about the general quality of the individual's relationships (range of 0-60), with higher scores indicating greater social support. Internal reliability ratings with this scale in previous studies have been excellent (α = .95) (Windle, 1991). Information on family and social problem severity was obtained with the ASI (see below).

Problem severity variables

The widely used and well-validated Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988) was used to assess level of depression (range of 0-63). The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McLellan et al., 1980) was also used to gather information on problem severity levels in four areas of functioning in addition to family/social: medical, employment, legal, and psychiatric. Composite scores provide an indication of overall problem severity in each area during the prior 30 days (range of 0.00 - 1.00, with higher scores indicating greater problem severity). The ASI has demonstrated adequate to good internal consistency, test-retest, and interrater reliabilities in different groups of substance abusers (McLellan et al., 1985).

2.6. Outcome Variable

Participants were categorized as “cocaine-free” for a period if they provided a urine sample negative for cocaine at the follow-up and reported no cocaine use since the last follow-up (i.e., either 3 or 6 months) on the TLFB. Participants were categorized as “using cocaine” for the follow-up period if they had either a cocaine positive urine or reported cocaine use on the TLFB. Participants were categorized as “missing” for the follow-up period if they failed to provide both TLFB and urine data, or if they provided a TLFB or urine test negative for cocaine but were missing the other measure (i.e., TLFB negative for cocaine, but no urine test).

2.7. Data Analyses

Preliminary analyses indicated little difference in results across the three studies, so data from all three studies were combined into one data set for all subsequent analyses. Pearson and Spearman correlations were done between baseline variables and the time-varying predictor variables. Each baseline variable retained for analysis was entered into a General Estimating Equation (GEE) model to predict cocaine-use status that included study, treatment condition, time, and a lagged variable assessing cocaine-use status at the follow-up prior to the follow-up serving as the outcome, as well as baseline variable × lagged cocaine use status, lagged cocaine use status × time, baseline variable × time, and baseline variable × lagged cocaine status × time interactions. These models were trimmed by removing non-significant interaction terms. Separate models were done initially for each baseline variable, followed by a multivariate model to identify which measures contributed independently to the prediction of outcome.

Analyses with time varying predictors were similar to those with the baseline variables. Here, the aim was to predict transitions in cocaine use status from one follow-up to the next with predictor variables measured at the earlier follow-up. The cocaine use status by time-varying predictor interactions examined whether the relation of the predictor variable to cocaine use status at the next follow-up varied as a function of cocaine use status at the point at which the predictor was assessed (i.e., the lagged cocaine use status variable). These GEE analyses were done separately for each predictor. Cocaine use at baseline, which was a highly significant predictor of cocaine-use state throughout the follow-up, was then added to these models to determine if similar results would be obtained with it in the model. Finally, multivariate analyses were done that combined significant baseline and time-varying variables to determine which variables made independent contributions to the prediction of cocaine use transitions.

3. Results

3.1. Cocaine Use Status Across the Follow-Ups

Approximately 60% of participants across the three studies were cocaine-free at the 3-month follow-up. This percentage dropped to about 50% for the remainder of the follow-ups out to 24 months, with rates about 10 percentage points lower in Study 1 than in Studies 2 or 3. Transition probabilities were as follows: Cocaine-free to cocaine-free-- .80, Using cocaine to using cocaine-- .80, Cocaine-free to using cocaine-- .20, Using cocaine to cocaine-free-- .20.

3.2. Correlations Between Predictor Variables

Among the 12 baseline predictors, only two of 66 correlations exceeded r= .30 (e.g., days of cocaine use × days of alcohol use, r= .59; number of prior drug treatments × number of prior alcohol treatments, r= .80). Among the 14 time varying predictors, eight of 91 correlations exceeded r= .30 (e.g., self-help behaviors × self-help beliefs, r= .50; ASI psychiatric severity × BDI, r= .49; self-efficacy × BDI, r= −.41; ASI family/social × ASI psychiatric severity, r= .35; ASI family/social × BDI, r= −.34; ASI psychiatric × ASI medical severity, r= .31; readiness to change × self-help beliefs, r= .31; coping × self-efficacy, r= .31).

3.3. Baseline Predictors of Transition to Cocaine-Free Status

Age was positively related to transitioning into cocaine-free status (estimate= 0.01, p< .05). A cocaine positive urine (estimate = −.61, p= .001), days of cocaine use in the prior 30 (estimate= −.19, p< .001), days of alcohol use in the prior 30 (estimate= −.10, p< .001), and years of education (estimate= −.07, p= .02) were negatively related to transitioning into cocaine-free status. Race, prior drug and alcohol treatments, major depression, alcohol dependence, and PTSD did not predict cocaine use transitions (all p> .25). Gender interacted significantly (estimate= −.92, p= .001) with lagged cocaine-use status to predict cocaine-use status in the subsequent follow-up period; among participants who were using cocaine, men were more likely to become cocaine-free at the next follow-up (22%) than were women (15%). None of the other variables interacted significantly with lagged cocaine-use status. When the baseline variables were entered into a multivariate model, only days of cocaine use in the prior 30 (z= −4.73, p< .0001) and cocaine urine toxicology (z= −2.84, p= .005) were significant.

3.4. Time-Varying Predictors of Transition to Cocaine-Free Status

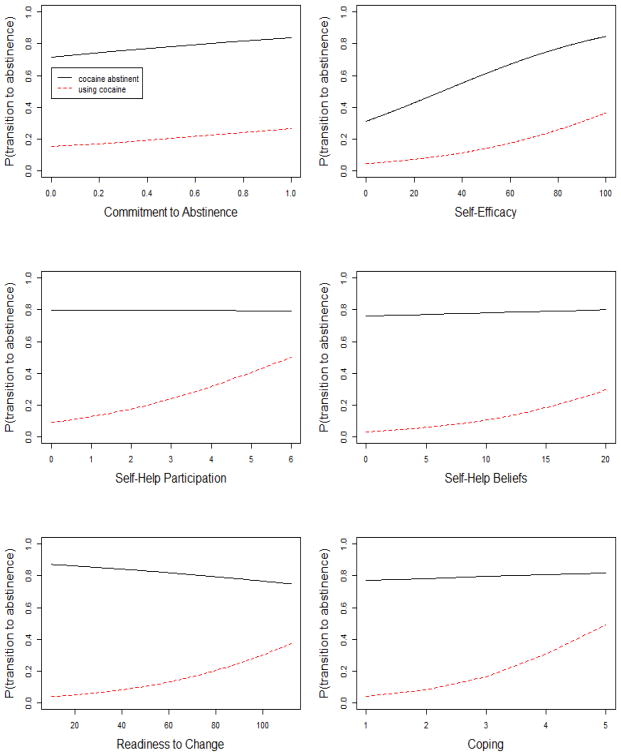

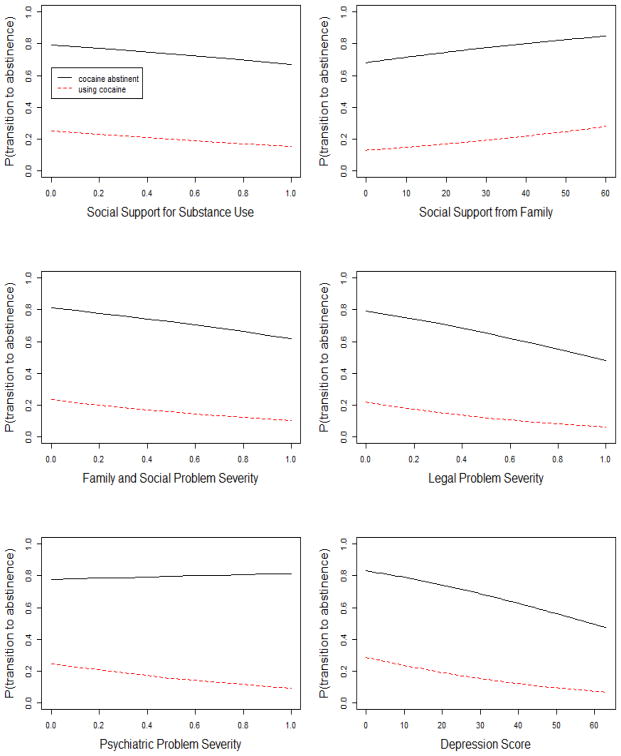

Each of the 14 time-varying predictors was first examined in separate transition models. Although correlations between self-help behaviors and self-help beliefs, and between the BDI and ASI psychiatric severity and self-efficacy exceeded r= .40, we decided to retain them all, as these variable assessed important factors in treatment outcome models and were therefore worth examining. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 1 and in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 1. Time Varying Variables.

| Main Effect* | Interaction With Current Use** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain and Variables | Z | P | Z | P |

| Self Help | ||||

| Commitment to abstinence | 4.41 | <.0001 | 0.20 | .84 |

| Self-help participation | 7.46 | < .0001 | −4.81 | < .0001 |

| Self-help beliefs | 4.68 | < .0001 | −3.13 | .0017 |

| Cognitive-Behavioral/Motivational | ||||

| Self-efficacy | 6.82 | < .0001 | −0.57 | .57 |

| Readiness to Change | 4.63 | < .0001 | −4.06 | < .0001 |

| Coping | 5.79 | < .0001 | −4.48 | < .0001 |

| Social Support | ||||

| General social support | 2.41 | .016 | 0.12 | .904 |

| Family/social problem severity | −2.16 | .016 | −0.08 | .933 |

| Social support for use | −1.66 | .097 | −0.60 | .548 |

| Other Stress | ||||

| Depression | −3.97 | <.0001 | 1.59 | .111 |

| Psychiatric severity | −3.00 | .0027 | 2.46 | .014 |

| Medical severity | −1.98 | .048 | 2.01 | .044 |

| Legal severity | −2.00 | .046 | −0.08 | .933 |

| Employment severity | 1.56 | .114 | −1.58 | .102 |

Main effect for lagged analyses that evaluate effect of variables on transition from current cocaine use state at that follow-up point to cocaine use state in subsequent follow-up.

Interaction between variables and cocaine use status at one follow-up in prediction of cocaine use status at next follow-up.

Figure 1.

Results of transition analyses with six time-varying predictor variables from Self-Help and Cognitive Behavioral/Motivational domains. Graphs show the probability of transitioning into a cocaine abstinent state at the subsequent follow-up (from 0.00 to 1.00), as a function of scores on the predictor variable and cocaine use state at the prior follow-up (e.g., cocaine abstinent or using cocaine). See text for a description of the scales for each predictor variable.

Figure 2.

Results of transition analyses with six time-varying predictor variables from Social Support and Stress domains. Graphs show the probability of transitioning into a cocaine abstinent state at the subsequent follow-up (from 0.00 to 1.00), as a function of scores on the predictor variable and cocaine use state at the prior follow-up (e.g., cocaine abstinent or using cocaine). See text for a description of the scales for each predictor variable. Results for Medical and Employment Problem Severities not shown.

3.4.1. Self-Help Variables

Commitment to abstinence, self-help behavior, and self-help beliefs were all positively related to transitions into cocaine-free status (p< .0001; See Table 1). Being committed to abstinence at one follow-up point raised the likelihood of transitioning to cocaine abstinence in the next follow-up for those who were non-abstinent and of remaining cocaine abstinent for those who were abstinent, in each case by 12 percentage points. With the two self-help variables, significant interactions with cocaine use status at the current time point were obtained. In patients who were already in the cocaine-free state, the probability of remaining abstinent at the next follow-up was unrelated to self-help behaviors or beliefs at that point. Conversely, in patients who were not cocaine-free, the probability of transitioning into the cocaine abstinence at the next follow-up was positively related to self-help behaviors (interaction p< .0001) and to self-help beliefs (interaction p= .0006) at the earlier follow-up, when use was occurring (see Figure 1). These main and interaction effects were consistent across all follow-ups (all time effects and interactions p> .10).

3.4.2. CBT and Transtheoretical Variables

Self-efficacy, coping, and readiness to change were all positively related to transitions into cocaine-free states (p< .0001; see Table 1). Participants who were currently cocaine-abstinent but had low self-efficacy had a greatly reduced likelihood of remaining abstinent in the next follow-up. Self-efficacy of 20% or less predicted less than a 40% chance of later abstinence, whereas self-efficacy greater than 80% predicted an 80% chance of later abstinence. Participants who were currently using cocaine and had low self-efficacy had essentially no chance of being cocaine abstinent in the next follow-up, whereas those with high self-efficacy had about a 35% chance of later abstinence (see Figure 1).

Early in the follow-up, participants with high coping scores had about a 20 percentage point greater likelihood of staying in or transitioning to cocaine abstinence at the next follow-up, whether they were using cocaine or not at the prior follow-up. However, by the middle of the follow-up, this effect was found only in those who were using cocaine. In this group, high coping scores increased the likelihood of transitioning to cocaine abstinence by about 50 percentage points. This effect produced a significant coping × current cocaine use × time interaction (Z= −2.32, p= .02). The relation of coping to cocaine use transitions averaged across follow-ups is presented in Figure 1.

Readiness to change also interacted significantly with cocaine use status at the current follow-up point. In patients who were cocaine abstinent, greater readiness was related to a slightly lower probability of remaining abstinent at the next follow-up. However, in patients who were not cocaine abstinent, readiness to change was positively related to transitioning into abstinence (interaction p< .0001; see Table 1). Participants who were currently using cocaine but had high readiness to change had almost a 40% chance of transitioning to cocaine abstinence, whereas those with low scores had essentially no chance (see Figure 1). These main and interaction effects were consistent across all follow-ups (all time effects and interactions p> .10).

3.4.3. Social Support Variables

Social support from family was positively related to transition into cocaine abstinence (p= .016), whereas ASI family/social problem severity and having someone who supported continued substance use were negatively related to transitioning into abstinence (p= .030 and .097, respectively) (see Table 1). For participants who were cocaine abstinent, having scores on these measures that indicated problems with social support resulted in a drop of about 15 percentage points in the likelihood of remaining cocaine free in the next follow-up. For participants who were currently using cocaine, there was about a 10 percentage point drop in the likelihood of transitioning to cocaine abstinence in those with bad, as compared good social support (see Figure 2). These variables did not interact with current cocaine-use status, and no significant effects or interactions with time were obtained.

3.4.4. Other Stress Variables

Greater depression (p< .0001), overall psychiatric severity (p< .003), and medical (p< .05) and legal (p< .05) problem severities predicted a lower likelihood of remaining in or transitioning to a cocaine-free state. Employment problem severity did not predict transitions (p= .11) (see Table 1). Participants who were currently cocaine abstinent and had low BDI scores had about an 80% chance of remaining abstinent in the next follow-up, whereas those with high BDI scores had less than a 60% chance of remaining abstinent. For participants currently using cocaine, those with low BDI scores had a 30% likelihood of transitioning to abstinence, whereas those with high BDI scores only had a 10% chance of becoming abstinent. Similarly, participants who were currently cocaine abstinent and had no legal problems had an 80% likelihood of remaining abstinent in the next follow-up, whereas those with relatively high legal severity had approximately a 50% chance of remaining abstinent. For those who were currently using cocaine, high legal severity reduced the likelihood of transitioning to abstinence from about 20% down to about 10% (see Figure 2).

Medical and psychiatric problem severity interacted significantly with cocaine use status at the current point (p< .05). In patients who were in the cocaine-free state, medical and psychiatric problem severity was unrelated to the probability of remaining in the cocaine free state at the next follow-up. However, in patients who were not cocaine free, higher medical or psychiatric severity was negatively related to transitioning into the cocaine-free state. These main and interaction effects with stress variables were consistent across all follow-ups.

3.5. Treatment Effects

Contrasts were included to compare telephone continuing care with TAU within each study (CBT and telephone monitoring were only included in one study each and were therefore not included in the treatment analysis). In 8 of the 14 models in which the time varying variables were examined, there was a significant treatment effect favoring telephone continuing care over TAU on the probability of remaining in or transitioning to cocaine abstinent across the follow-up. This treatment effect was larger (p values between .016 and .056) in models in which the time-varying variable was more significant (i.e., self-efficacy, commitment to abstinence, readiness to change, self-help participation) and smaller (p values between .16 and .24) in models in which the predictor variable was less significant (i.e., ASI problem severity composite scores).

3.6. Controlling for Baseline Cocaine Use in Transition Analyses

The two strongest baseline predictors of transition status were days of cocaine use in the prior 30 and cocaine urine toxicology. These variables were added as covariates to the analyses with time-varying predictors, to determine if the effects held. Main effects for all variables remained unchanged, except for ASI medical problem severity, which was no longer significant. The significant interactions of predictor variables with current cocaine use status were unchanged, except for the interaction with self-help beliefs, which was no longer significant. The significant telephone continuing care treatment effect present in most models slipped to the level of a trend once baseline cocaine use was included (p < .10).

3.7. Multivariate Transition Analysis

The model was built by adding in predictor variables, starting with the most significant, until no other predictors were significant in the model. The predictors retained in the model were self-efficacy (z=6.71, p< .0001), self-help participation (z=4.99, p< .0001), commitment to abstinence (z=4.50, p< .0001), and self-help beliefs (z=2.12, p= .034). The self-help participation × current cocaine use status interaction term was also still significant (z=−3.23, p= .001), although none of the other interactions entered the model. The telephone continuing care vs. TAU contrast was significant at the level of a trend in this model (z= 1.67, p< .10). Adding cocaine use at baseline to the model did not affect the results, except that the treatment contrast effect no longer reached the level of a trend (z=1.23, p= .22).

4. Discussion

Cocaine use status during each follow-up period over 24 months was highly predictive of cocaine use status in the next follow-up period. However, 20% of patients who were using cocaine during one point were cocaine free during the subsequent period, and 20% who were cocaine-free at one point relapsed during the subsequent follow-up. Less cocaine and alcohol use in the 30 days prior to baseline (i.e., early in IOP) predicted continuation of or shift into cocaine abstinence, as did older age, and less education. Men were also more likely than women to transition from using cocaine in one follow-up to cocaine abstinence at the next. The findings with substance use and age are consistent with prior research (Alterman et al., 1997; Kampman et al., 2002; Reiber et al., 2002), although the lack of effects for treatment history and co-occurring alcohol dependence are not. Moreover, prior research has generally not found sex differences in treatment outcomes (Green, 2006; Greenfield et al., 2007).

The time varying variables were not highly correlated with each other, with less than 9% of the correlations exceeding r= .30. For participants who were cocaine abstinent at a particular follow-up, scores on 7 of 14 time-varying variables assessed at that follow-up were significantly associated with remaining cocaine abstinent at the next follow-up. In a few cases, the effects were fairly dramatic; for example, the likelihood of continued cocaine abstinence was only 40% for participants with low self-efficacy versus 80% for those with high self-efficacy. Notably, self-help participation, self-help behaviors, coping, and readiness to change did not predict maintenance of abstinence in those who were currently abstinent.

In participants who were not currently cocaine abstinent, 13 of 14 time-varying variables predicted transition into cocaine abstinence at the next follow-up. Once again, some of these effects were substantial. Participants with little or no self-help participation had less than a 20% chance of becoming cocaine abstinent at the next follow-up, whereas those with considerable self-help involvement despite their recent cocaine use had almost a 50% chance of becoming cocaine abstinent. Similar effects of equal magnitude were found with coping and readiness to change measures.

These results are generally consistent with prior research on the impact of self-help participation, self-efficacy, coping, commitment to abstinence, depression, poor social support, and other stressors assessed during follow-up on cocaine and alcohol use outcomes (Connors et al., 1996; Hser et al., 2008; Kissin et al., 2003; McKay et al., 2001; Miller et al., 1996; Moos et al, 1990; Scott et al., 2005; Stulz et al., 2011; Weisner et al., 2003; Witkiewitz, 2011; Witkiewitz & Masyn, 2008). However, these studies have often not controlled for substance use at the point at which the predictors were assessed, and have not determined whether these effects were found in participants who were abstinent at a given point in the follow-up or in those who were using. In the present study, most of the results were remarkably consistent across the 6-8 transition points in the 24 month follow-ups. Consistency across multiple time points has not been looked at in most prior research.

One of the other notable findings in the study concerned the different effects associated with general psychiatric severity, as assessed with the ASI, and depression, as assessed with the BDI. In participants who were cocaine abstinent, ASI psychiatric severity scores did not predict cocaine use in the next follow-up. However, the likelihood of remaining cocaine abstinent was strongly related to current BDI scores—high current depression scores predicted less than a 60% chance of remaining cocaine abstinent. This result is consistent with prior studies that have found that the persistence of depression after treatment predicts worse substance use outcomes (Greenfield et al., 1998; Stulz et al., 2011).

One important issue addressed by the present study was whether any of the time-varying variables made independent contributions to the prediction of cocaine use when other variables were included in the model. The results of the transition analyses with time-varying variables generally held up when cocaine use at baseline was added as a covariate. These models represented fairly stringent tests of the predictive power of the time varying variables, as they controlled for both baseline (i.e., early treatment) cocaine use and cocaine use status at the time the predictor variables were assessed. In analyses that included multiple time-varying predictors and baseline cocaine use, the variables that contributed independently to the prediction of transitions in cocaine use states were self-efficacy, self-help participation (for those who were currently using cocaine), commitment to abstinence, and self-help beliefs. Three of these four variables assessed self-help group related factors, which highlights the important role that self-help involvement and beliefs play in sustained recoveries in this population.

Strengths and Limitations

The study had a number of important strengths, including a large sample drawn from three continuing care studies, multiple assessments over 24 months, good follow-up rates, biological and self-report measures of cocaine use, inclusion of multiple predictor measures from four domains, and use of transition analyses that enabled examination of predictors of sustained cocaine abstinence and of transitions from cocaine use to abstinence. At the same time, the study had several limitations. With the exception of the treatment comparisons, the research was correlational rather than experimental. Therefore, it cannot be stated conclusively that the predictor variables caused transitions in cocaine use status, or that inducing changes in the predictors (e.g., raising self-efficacy, increasing coping and self-help group attendance) would result in higher abstinence rates. The participants were largely inner city, African American males, and different results might be obtained with other populations. Some factors that may be important predictors, such as craving and neurocognitive functioning, were not assessed. The time varying predictor variables were all self-report, and 8 of the 14 examined were available from only two of three studies included in the analyses. Finally, only one urine sample was obtained per follow-up period. Some participants who provided cocaine free urines could have been miss-classified in a given period if they were using cocaine earlier in the period but did not report it on the TLFB.

Clinical Implications

The research has several implications for the provision of extended continuing care or other forms of outcomes monitoring, recovery support, or disease management in this population. In individuals who are currently cocaine abstinent, it does not appear necessary to focus on or stress self-help involvement, self-help beliefs, readiness to change, or coping behaviors. However, in individuals who have continued to use cocaine or relapsed to cocaine use, direct attention to these issues in individuals with low scores may contribute to subsequent improvements in cocaine use. On the other hand, all cocaine dependent patients—whether they are currently abstinent or not—appear to be vulnerable to relapse when self-efficacy drops or depression increases. This suggests that there may be clinical benefit in routinely monitoring self-efficacy and depression in cocaine dependent patients, and modifying treatment when worrisome scores are obtained (McKay, 2009; Murphy, Lynch, McKay, Oslin, & TenHave, 2007). This may be of somewhat greater importance in women, who are more likely to transition from cocaine abstinence to use than are men. The relatively low correlations between most predictor variables suggest that cocaine abstinence is not accounted for by one general factor, and that a number of the measures examined here provide independent information on risk for relapse. Finally, the results provide further evidence that the addition of telephone-based continuing care to standard IOP treatment can improve outcomes for cocaine dependent patients.

Acknowledgments

Support provided by NIDA and NIAAA grants: K24 DA029062 (McKay, PI), R01 DA020623 (McKay, PI), R01 AA14850 (McKay, PI). We also thank the administrative and clinical staffs at the Philadelphia VAMC, NorthEast Treatment Centers, and Presbyterian Hospital for their participation in the three studies included in this article. Finally, we thank the patients from these programs who graciously participated in our research studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aharonovich E, Amrhein PC, Bisaga A, Nunes EV, Hasin DS. Cognition, commitment language, and behavioral change among cocaine-dependent patients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:557–562. doi: 10.1037/a0012971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharonovich E, Hasin DS, Brooks AC, Liu X, Bisaga A, Nunes EV. Cognitive deficits predict low treatment retention in cocaine dependent patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi J, Kampman KM, Oslin DM, Pettinati HM, Dackis C, Sparkman T. Predictors of treatment outcome in outpatient cocaine and alcohol dependence treatment. The American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18:81–86. doi: 10.1080/10550490802545174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alterman AI, Kampman K, Boardman CR, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, McKay JR, Maany I. A cocaine-positive baseline urine predicts outpatient treatment attrition and failure to attain initial abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;46:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annis HM, Martin G. The Drug-Taking Confidence Questionnaire. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation of Ontario; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Power ME, Bryant K, Rounsaville BJ. One-year follow-up status of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Psychopathology and dependence severity as predictors of outcome. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1993;181:71–79. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Gordon LT, Nich C, Jatlow P, Bisighini RM, Gawin FH. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for ambulatory cocaine abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:177–187. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Maisto SA, Zywiak WH. Understanding relapse in the broader context of post-treatment functioning. Addiction. 1996;91:S173–S190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK. Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice. 2007 Dec;:45–55. doi: 10.1151/ascp074145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R, Foss MA. The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment careers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:S51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ. Reliability and validity of 6-month timeline reports of cocaine and heroin use in a methadone population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:843–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research version, Patient edition (SCID-I/P) New York City, New York: Biometrics research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Kunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallop RJ, Crits-Christoph P, Ten Have TR, Barber JP, Frank A, Griffin MG, Thase ME. Differential transitions between cocaine use and abstinence for men and women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:95–103. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CA. Gender and use of substance abuse treatment services. Alcohol Research and Health. 2006;29:55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, Lincoln M, Hien D, Miele GM. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Weiss RD, Muenz LR, Vage LM, Kelly JF, Bello LR, et al. The effect of depression on return to drinking: A prospective study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:259–265. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman DA. Effects of commitment to abstinence, positive moods, stress, and coping on relapse to cocaine use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:526–532. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havassy BE, Wasserman DA, Hall SM. Social relationships and abstinence from cocaine in an American treatment sample. Addiction. 1995;90:699–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90569911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbeck DM, Hser YI, Lu ATH, Stark ME, Paredes A. A 12-year follow-up study of psychiatric symptomatology among cocaine-dependent men. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:12974–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Badger GJ, Budney AJ. Initial abstinence and success in achieving longer term cocaine abstinence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:377–386. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Evans E, Huang D, Brecht ML, Li L. Comparing the dynamic course of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine use over 10 years. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1581–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Joshi V, Anglin MD, Fletcher B. Predicting posttreatment cocaine abstinence for first-time admissions and treatment repeaters. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:666–671. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.5.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Stark ME, Paredes A, Huang D, Anglin MD, Rawson R. A 12-year follow-up of a treated cocaine-dependent sample. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K. Circles of Recovery: Self-Help Organizations for Addictions. Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HB. Psychosocial stress from the perspective of self theory. In: Kaplan HB, editor. Psychosocial Stress: Perspectives on structure, theory, life course, and methods. New York: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 175–244. [Google Scholar]

- Kampman KM, Volpicelli JR, Mulvaney F, Rukstalis M, Alterman AI, Pettinati H, Weinrieb RM, O'Brien CP. Cocaine withdrawal severity and urine toxicology results from treatment entry predict outcome in medication trials for cocaine dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissin W, McLeod C, McKay J. The longitudinal relationship between self-help group attendance and course of recovery. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2003;26:311–323. [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Beattie MC, Noel N, Stout RL. Matching treatment focus to patient social investment and support: 18 month follow-up results. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:296–307. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Comparison of alcoholics' self-reports of drinking behavior with reports of collateral informants. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:106–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR. Treating substance use disorders with adaptive continuing care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, O'Brien CP, Koppenhaver JM, Shepard DS. Continuing care for cocaine dependence: Comprehensive 2-year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:420–427. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, O'Brien CP, Koppenhaver J. Group counseling versus individualized relapse prevention aftercare following intensive outpatient treatment for cocaine dependence: initial results. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:778–788. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Snider EC. Treatment goals, continuity of care, and outcome in a day hospital substance abuse rehabilitation program. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:254–259. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.2.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Foltz C, Stephens RC, Leahy PJ, Crowley EM, Kissin W. Predictors of alcohol and crack cocaine use outcomes over a 3-year follow-up in treatment seekers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005a;28:S73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Pettinati HM. The effectiveness of telephone based continuing care for alcohol and cocaine dependence: 24 month outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005b;62:199–207. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Ratichek S, Morrison R, Koppenhaver J, Pettinati HM. The effectiveness of telephone-based continuing care in the clinical management of alcohol and cocaine use disorders: 12-month outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:967–979. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Maisto SA, O'Farrell TJ. End-of-treatment self-efficacy, aftercare, and drinking outcomes of alcoholic men. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 1993;17:1078–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Merikle E, Mulvaney FD, Weiss RV, Koppenhaver JM. Factors accounting for cocaine use two years following initiation of continuing care. Addiction. 2001;96:213–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9622134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Van Horn D, Lynch KG, Ivey M, Cary MS, Drapkin M, Coviello D, Plebani JG. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. An adaptive approach for identifying cocaine dependent patients who benefit from extended continuing care. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Van Horn DH, Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Ivey M, Ward K, Drapkin ML, Becher JR, Coviello DM. A randomized trial of extended telephone-based continuing care for alcohol dependence: Within-treatment substance use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:912–923. doi: 10.1037/a0020700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Weiss RV. A review of temporal effects and outcome predictors in substance abuse treatment studies with long-term follow-ups. Preliminary results and methodological issues. Evaluation Review. 2001;25:113–161. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr H, O'Brien C. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: Reliability and validity in three centers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Westerberg VS, Harris RJ, Tonigan JS. What predicts relapse? Prospective testing of antecedent models. Addiction. 1996;91:S155–S172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Finney JW, Cronkite RC. Alcoholism treatment: Context, process, and outcome. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Long-term influence of duration and frequency of participation in Alcoholics Anonymous on individuals with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:81–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA, Lynch KG, McKay JR, Oslin DW, Ten Have TR. Developing adaptive treatment strategies in substance abuse research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:S24–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poling J, Kosten TR, Sofuoglu M. Treatment outcome predictors for cocaine dependence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:191–206. doi: 10.1080/00952990701199416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Silverman K, Higgins ST, Brooner RK, Montoya I, Schuster CR, Cone EJ. Cocaine use early in treatment predicts outcome in a behavioral treatment program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:691–696. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente C. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing The Traditional Boundaries of Therapy. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Co.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Fava J. Measuring processes of change: Applications to the cessation of smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:520–528. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. American Journal Community Psychology. 1983;11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project Match Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcoholism. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiber C, Ramirez A, Parent D, Rawson RA. Predicting treatment success at multiple timpoints in diverse patient populations of cocaine-dependent individuals. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:35–48. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Martin RA, Eaton CA, Monti PM. Cocaine craving as a predictor of treatment attrition and outcomes after residential treatment for cocaine dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:641–648. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Mooney ME, Green CE, Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Swann AC, Moeller FG. Baseline neurocognitive profiles differentiate abstainers and non-abstainers in a cocaine clinical trial. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2009;28:250–257. doi: 10.1080/10550880903028502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Foss MA, Dennis ML. Pathways in the relapse--treatment--recovery cycle over 3 years. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:S63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM. A national 5-year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:538–544. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Fletcher BW, Hubbard RL, Anglin MD. A national evaluation of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:507–514. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueland L, Crits-Christoph P, Gallop R, Barber JP, Griffin ML, Thase ME, Daley D, Frabk A, Gastfriend DR, Blaine J, Connolly MB, Gladis M. Retention in psychosocial treatment of cocaine dependence: predictors and impact on outcome. The American Journal on Addictions. 2002;11:24–40. doi: 10.1080/10550490252801611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Maisto SA, Sobell MB, Cooper A. Reliability of alcohol abusers' self-reports of drinking behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1979;17:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: Assessing normal drinkers' reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. British Journal of Addiction. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Beattie MC, Longabaugh R, Noel N. Factors affecting correspondence between patient and significant other reports of drinking [abstract] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1989;12:336. [Google Scholar]

- Stulz N, Thase ME, Gallop R, Crits-Christoph P. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: the role of depressive symptoms. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Toscova R, Miller WR. Meta-analysis of the literature on Alcoholics Anonymous: sample and study characteristics moderate findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:65–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn DH, Drapkin M, Ivey M, Thomas T, Domis SW, Abdalla O, Herd D, McKay JR. Voucher incentives increase treatment participation in telephone-based continuing care for cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114:225–228. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Delucchi K, Matzger H, Schmidt L. The role of community services and informal support on five-year drinking trajectories of alcohol dependent and problem drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:862–873. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Mazurick C, Berkman B, Gastfriend DR, Frank A, Barber JP, Blaine J, Salloum I, Moras K. The relationship between cocaine craving, psychosocial treatment, and subsequent cocaine use. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1320–1325. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. The difficult tempermant in adolescence: Associations with substance abuse, family support, and problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1991;47:310–315. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199103)47:2<310::aid-jclp2270470219>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K. Predictors of heavy drinking during and following treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:426–438. doi: 10.1037/a0022889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: That was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist. 2004;59:224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Masyn K. Drinking trajectories following an initial lapse. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:157–167. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Villarroel NA. Dynamic association between negative affect and alcohol lapses following alcohol treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:633–644. doi: 10.1037/a0015647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak WH, Neighbors CJ, Martin RA, Johnson JE, Eaton CA, Rohsenow DJ. The Important People Drug and Alcohol interview: psychometric properties, predictive validity, and implications for treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]