Hematologic malignancies are diseases that mainly affect older subjects. Multiple myeloma,1 myelodysplastic syndromes2 and chronic myeloid leukemia3 are common in advanced age. Nevertheless, there is evidence that older patients with hematologic malignancies have often been excluded from clinical trials (CTs).4,5 Their exclusion prevents clinicians from obtaining information concerning the efficacy and safety of treatments in older patients and might represent an important barrier to the treatment of these patients.6 Published literature reflects trials performed some years before their publication. It is not known whether older individuals are gradually being included in more trials as a consequence of the aging of the population and of the recommendation provided by Regulatory Agencies, e.g. FDA and ICH, to include older individuals in CTs.7,8 The aims of this study were to assess the presence and the extent of underrepresentation of older individuals in ongoing CTs on hematologic malignancies registered in an online open-access CT registry maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO), and to evaluate the relationship between eligibility criteria and trial characteristics.

Information regarding ongoing CTs was obtained from the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO-ICTRP).9 This database collects trials registered in the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Register, the US Food and Drug Administration Registry, the Netherlands Trials Registry, the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry, and the Japan Primary Registries Network. A search was performed using the following keywords: “cancer” OR “tumor” OR “neoplasm” OR “malignancy”, in the condition field; “all” in the register field; and “recruiting” in the recruitment field. We identified the most relevant information to collect from the study protocol of each CT. The methodology was adapted from that used in the PREDICT study.10 We classified hematologic malignancies based on 2008 WHO classification.11 Concerning exclusion criteria, we assessed the presence of an upper age limit (explicit exclusion) and other exclusion criteria (implicit criteria) that might potentially lead to a reduction in the number of older individuals included in the trials, such as exclusion by comorbidity, cognitive or physical impairment, reduced life expectancy, pharmacological therapy, visual or hearing deficits, or inability to attend the follow up appointments.

Descriptive statistics have been performed for discrete and continuous variables. The analysis of contingency tables for categorical variables was supported by Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for sparse tables or for tables larger than 2 × 2. Univariable logistical regression models were used to identify variables more associated with the specific cause of exclusion on the basis of χ2 Wald statistics (P>χ2 Wald <=0.25). A linearity study was performed for continuous variables and transformations have been applied when necessary. Any variable whose univariable test has P<0.25 has been chosen as a candidate for the multivariable logistical regression models. Multivariable logistical regression model computation with automatic selection of the best model (backward and stepwise methods) has been performed to discover variables significantly associated with each cause of exclusion using SAS software (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

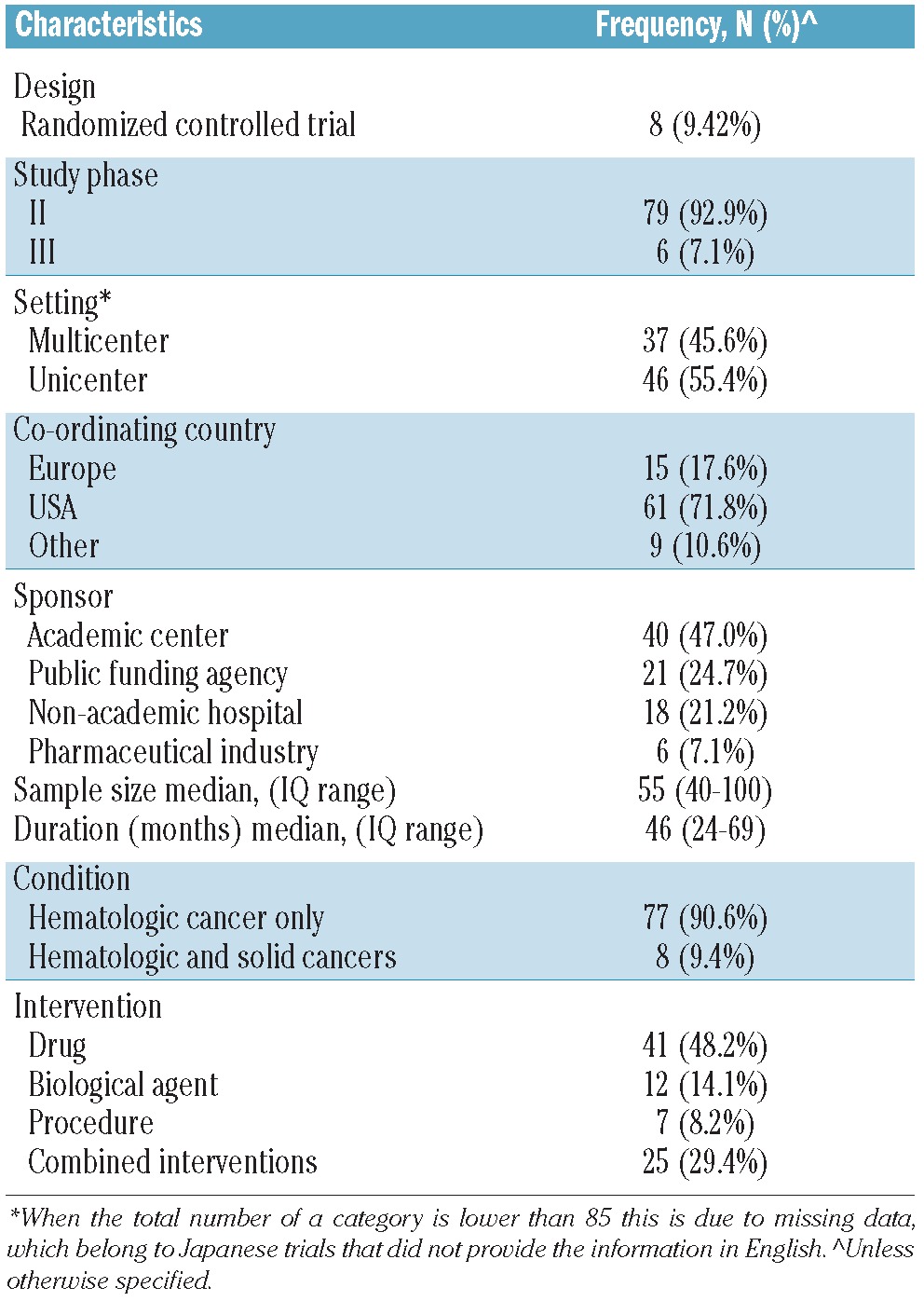

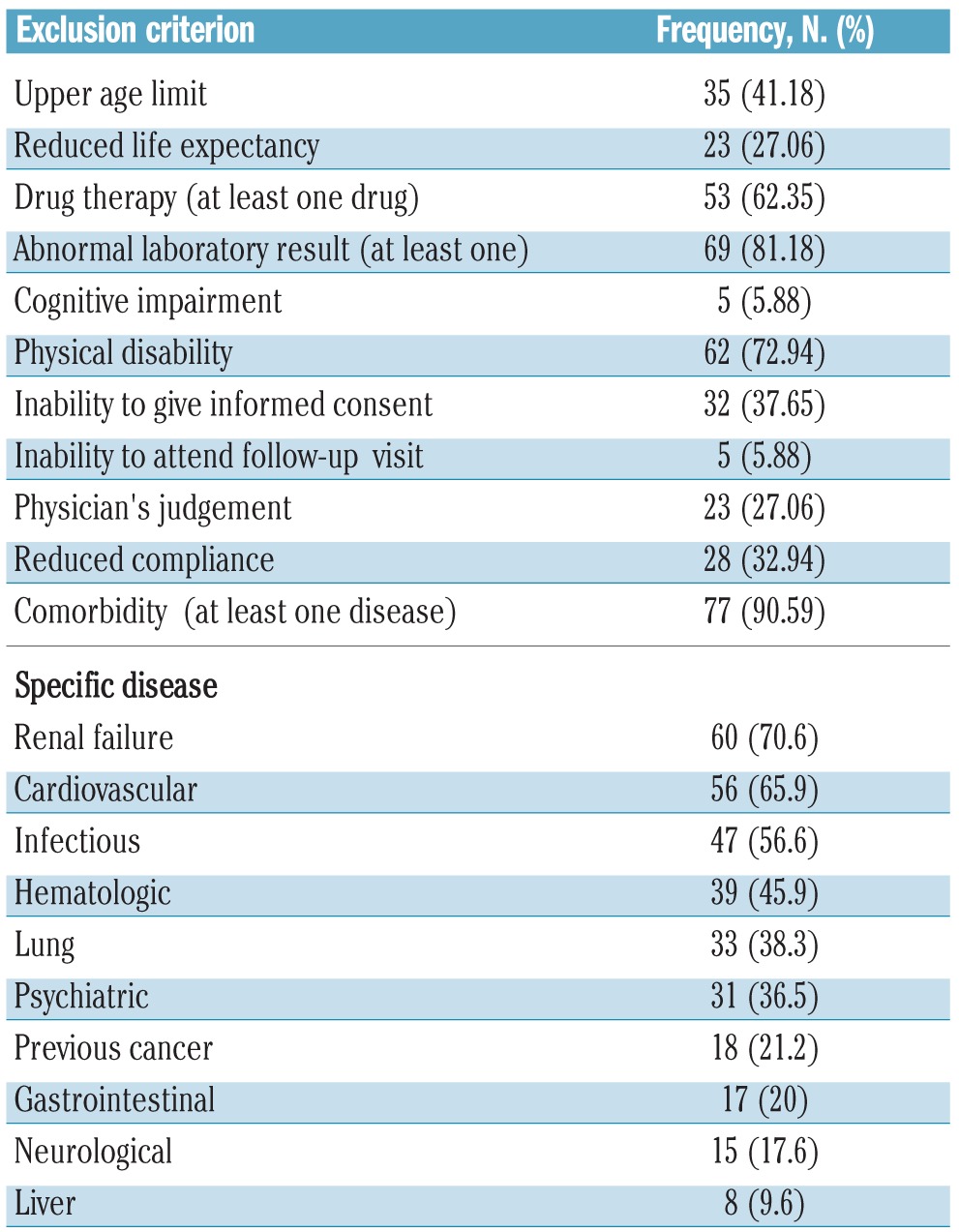

As of February 3rd, 2011, there were 9074 registered trials recruiting patients with cancer in the WHO-ICTRP. A total of 8807 studies were excluded because they investigated solid tumors. From the remaining 267 CTs, 182 were excluded for the following reasons: 106 were phase I studies, which might reasonably exclude older patients considering their highly experimental nature, 9 because of their observational design, 6 because they involved children, 14 because cancer was not the main target condition (e.g. graft-versus-host disease), 10 because the primary purpose was not treatment, 33 because they adopted a high-dose radiation protocol which is not recommended in older subjects, 3 because they were pilot studies, and 2 because they were registered twice. Our analysis focused on 85 CTs. The main characteristics are described in Table 1. The majority of CTs (75.9%) were registered in the USA registry. Most CTs planned to enroll patients with different types of hematologic malignancies (53%). The most common malignancies were mature B-cell cancer (74%), acute myeloid leukemia (33%), myelodysplastic syndromes (30.5%), Hodgkin’s lymphoma (26%), and myeloproliferative neoplasms (26%). The frequencies of exclusion criteria are given in Table 2. The most common exclusion criteria were the presence of at least one comorbidity (91%), at least one abnormal laboratory result (81%), the use of one or more specific drugs (67%), and upper age limit (41%). The mean upper age limit was 68 years (SD 8.3). Univariable analysis showed that a longer duration of the trial and specific blood malignancies (leukemia, myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic syndromes) were associated with exclusion because of upper age limit. Moreover, if the trial promoter was an academic center, there was the highest probability of exclusion for upper age limit (P<0.03). In the logistical model, only a longer duration of the trial remained significantly associated. An upper age limit was an exclusion criterion in 52% of the trials registered before 2008 (n=21) compared to 31% in those registered after 2008 (n=14; P<0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of ongoing clinical trials regarding hematologic cancer in older patients (n=85)*.

Table 2.

Frequencies of exclusion criteria that might negatively affect the inclusion of older individuals in ongoing clinical trials regarding hematologic malignancies.

The main finding of our study is that older patients are still commonly excluded from CTs on hematologic malignancies. The age cut off is in the majority of CTs is below 70 years, an age at which the risk of several hematologic malignancies increases.1,2 This threshold is also below the average life expectancy in industrialized countries: at 70 years of age the majority of subjects are still independent or with only minor problems with the more complex activities of daily living. The paucity of data on treatment efficacy and safety is likely to contribute to the high rate of undertreatment of cancer patients,12,13 including those with hematologic malignancies.14 This is also suggested by the fact that novel agents have been shown to improve the outcome of younger patients with multiple myeloma and to be effective also in older patients,15–17 but very little progress has been achieved in survival in the latter group.18,19 Moreover, the toxicity and the outcome of autologous stem cell transplant in selected older patients appear comparable to those in younger patients.20

All this leads us to conclude that the exclusion of older subjects is inappropriate and more elderly individuals should be enrolled in CTs. Although recent years has seen a fall in the percentage of trials with age as exclusion criterion, this does not guarantee that older patients will be included in CTs. Ongoing trials have a multiplicity of exclusion criteria that could limit the participation of older patients, in particular concomitant diseases and pharmacological therapies. Our study has some limitations. First, our analysis was restricted to the WHO-ICTRP registry, which is not necessarily representative of the ongoing trials worldwide, e.g. at the time when data were downloaded from the database the European database of CTs was not included. Moreover, we examined only eligibility criteria and we cannot know the characteristics of the sample that will be finally enrolled.

The increasing number of older subjects aging in better clinical condition will necessarily require a change in this persistent form of age-related discrimination.

Footnotes

Financial and other disclosures provided by the author using the ICMJE (www.icmje.org) Uniform Format for Disclosure of Competing Interests are available with the full text of this paper at www.haematologica.org.

References

- 1.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Ludwig H, Dimopoulos MA, Bladé J, Mateos MV, et al. Personalized therapy in multiple myeloma according to patient age and vulnerability: a report of the European Myeloma Network (EMN). Blood. 2011;118(17):4519–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sekeres MA. The epidemiology of myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24(2):287–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohrbacher M, Hasford J. Epidemiology of chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML). Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2009;22(3):295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engert A, Ballova V, Haverkamp H, Pfistner B, Josting A, Dühmke E, et al. German Hodgkin's Study Group Hodgkin's lymphoma in elderly patients: a comprehensive retrospective analysis from the German Hodgkin's Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5052–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rohrbacher M, Berger U, Hochhaus A, Metzgeroth G, Adam K, Lahaye T, et al. Clinical trials underestimate the age of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients. Incidence and median age of Ph/BCR-ABL-positive CML and other chronic myeloproliferative disorders in a representative area in Germany. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):602–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crome P, Lally F, Cherubini A, Metzgeroth G, Adam K, Lahaye T, et al. Exclusion of older people from clinical trials: professional views from nine European countries participating in the Predict study. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(8):667–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration Guideline for the study of drugs likely to be used in the elderly. 1989. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm072048.pdf Accessed September 12, 2012

- 8.International conference on harmonization of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. Studies in support of special populations: geriatric E7, 1994. http://www.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA483.pdf Accessed September 12, 2012

- 9.World Health Organization. International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. [Accessed March 8th, 2012]. http://apps.who.int/trialsearch.

- 10.Cherubini A, Oristrell J, Pla X, Ruggiero C, Ferretti R, Diestre G, et al. The persistent exclusion of older subjects from ongoing trials on heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(6):550–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours, Volume 2 IARC WHO Classification of Tumours, No 2 IARC; 2008. http://apps.who.int/bookorders/anglais/detart1.jsp?sesslan=1&codlan=1&codcol=70&codcch=4002 Accessed September 12, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Blagojevic S, Vlastos AT, Vlastos G. Older female cancer patients: importance, causes, and consequences of undertreatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(14):1858–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeber JE, Copeland LA, Hosek BJ, Karnad AB, Lawrence VA, Sanchez-Reilly SE. Cancer rates, medical comorbidities, and treatment modalities in the oldest patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;67(3):237–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodon P, Linassier C, Gauvain JB, Benboubker L, Goupille P, Maigre M, et al. Multiple myeloma in elderly patients: presenting features and outcome. Eur J Haematol. 2001;66(1):11–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Caravita T, Merla E, Capparella V, Callea V, et al. Oral melphalan and prednisone chemotherapy plus thalidomide compared with melphalan and prednisone alone in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9513):825–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mateos MV, Hernandez JM, Hernandez MT, Gutiérrez NC, Palomera L, Fuertes M, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone in elderly untreated patients with multiple myeloma: results of a multicenter phase 1/2 study. Blood. 2006;108(7):2165–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, Fonseca R, Vesole DH, Williams ME, et al. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(1):29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Recent major improvements in long-term survival of younger patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111(5):25216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaapveld M, Visser O, Siesling S, Schaar CG, Zweegman S, Vellenga E. Improved survival among younger but not among older patients with multiple myeloma in the Netherlands, a population-based study since 1989. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(1):160–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fayers PM, Palumbo A, Hulin C, Waage A, Wijermans P, Beksaç M, et al. Thalidomide for previously untreated elderly patients with multiple myeloma: meta-analysis of 1685 individual patient data from 6 randomized clinical trials. Blood. 2011;118(5):1239–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]