Abstract

Associations between stress and breast cancer highlight stressful life events as barriers to breast cancer screening, increased stress due to a breast cancer scare or diagnosis, or the immunosuppressive properties of stress as a risk factor for breast cancer occurrence. Little is known, however, about how women’s reactions to stressful life events impact their breast health trajectory. In this study, we explore how reactions to stressors serve as a potential barrier to breast cancer screening among Black women. We apply a gender-specific, culturally responsive stress-process framework, the Stress and ‘Strength’ Hypothesis (“strength hypothesis”), to understand links between the ‘Strong Black Woman role’ role, Black women’s stress reactions and their observed screening delays. We conceptualize strength as a culturally prescribed coping style that conditions resilience, self-reliance and psychological hardiness as a survival response to race-related and gender-related stressors. Using qualitative methods, we investigate the potential for this coping mechanism to manifest as extraordinary caregiving, emotional suppression and self-care postponement. These manifestations may result in limited time for scheduling and attending screening appointments, lack of or delay in acknowledgement of breast health symptoms and low prioritization of breast care. Limitations and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: Black women, strength, stress, breast cancer screening, coping

Introduction

The state of Black women’s breast health garners the need for national attention. In comparison with women across all racial and ethnic groups, the breast health trajectory of Black women is characterized by the highest prevalence rates of breast cancer, highest risk for late-stage diagnosis at first detection and the lowest survival rates from breast cancer at any stage and at any age (American Cancer Society, 2009).

Standard risk factors for breast cancer include a personal history of breast cancer, familial history of breast cancer, being young at first period, starting menopause late, never being pregnant or having first child after age 30 years, and having mutated breast cancer gene (BRCA1, BRCA2) (American Cancer Society, 2009; Campbell, 2002). Research conducted to establish links between environmental factors (e.g. cosmetics, personal care products and plastics) and breast cancer risk is promising but inconclusive (American Cancer Society, 2009).

In comparison with other groups of women, Black women may be at increased risk of experiencing breast cancer in their lifetimes as a function of higher obesity rates (Gerend & Pai, 2008; Lantz et al., 2006)—53% in comparison with 37% of White women (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009)— and increased likelihood for developing triple negative breast cancer. Specifically, Black women are three times more likely than White women to have receptor-negative genes (triple negative) that fail to respond to receptor-targeted treatments (Stead et al., 2009). Moreover, triple negative breast cancer is the most aggressive form of breast cancer and more likely to recur, further impacting the breast health trajectory of Black women.

Various psychosocial factors may also be preventing women from engaging in health decisions leading to early detection. Women’s barriers to breast cancer screenings typically include three categories: structural, clinical and personal. Structural barriers to breast cancer screenings involve limited access to quality care (Peek, Sayad, & Markwardt, 2008), absence of a usual source of care (Conway-Phillips & Millon-Underwood, 2009) and low socio-economic status (Peek et al., 2008). Clinical barriers to screening occur when women fail to get screened as a result of negative interactions with providers (Peek et al., 2008) or receive limited information about breast cancer screening from their provider (Conway-Phillips & Millon-Underwood, 2009). Cancer fatalism and lack of breast cancer awareness are considered personal barriers to breast cancer screening (Conway-Phillips & Millon-Underwood, 2009; Frisby, 2012; Gullatte, Brawley, Kinney, Powe, & Mooney, 2010; Peek et al., 2008).

In the present study, we explore the potential for Black women’s stress reactions to further explain the observed delays in breast cancer screening. Prior research correlating stress and breast cancer has often been conducted in isolation of contextual factors that shape women’s reactions to stressors. Most common are examinations of stressors as a potential barrier to breast cancer screening (Peek et al., 2008), increased stress experiences after a breast cancer scare or diagnosis (Blow et al., 2011), or the immunosuppressive properties of stress in relation to malignant tumour growth (Chida, Hamer, Wardle, & Steptoe, 2008; Duijts, Zeegers, & Borne, 2003; Hilakivi-Clarke, Rowland, Clarke, & Lippman, 1994; Lillberg, 2003). Although these examinations establish the salience of stressors to the breast health continuum, further evidence is needed to understand how personal and social variables forecast women’s reactions to stressors and their decisions to get screened.

We address this gap by conceptualizing the stress-response processes of Black women within both gendered and cultural contexts. Studies of gender differences in coping are anchored by two paradigms. The first, ‘fight-or-flight’ (Cannon, 1929), describes the coping strategies of men faced with stressors, who either confront (fight) or avoid (flight) imposing stressors (Cannon, 1929). Conversely, women are likely to engage in ‘tend-and-befriend’ (Taylor et al., 2000) when faced with stressful situations enlisting protective strategies such as caring for themselves and loved ones (tend) and gaining support from social network members (befriend). The fight-or-flight paradigm has typically been applied to understand the response to acute, often life-threatening stressors, whereas tend-and-befriend has been applied to both acute and chronic stressors.

Various contextual factors, including cultural values and beliefs, impact the strategies enlisted to manage stressors and demands in the lives of ethnic minorities (Aranda & Knight, 1997; Brantley, O’Hea, Jones, & Mehan, 2002). Among African Americans, these factors include ‘a reliance on the family and the community, cooperation, a belief in hard work, achievement, and responsibility, and religious beliefs and rituals’ (Daley, Jennings, Beckett, & Leashore, 1995), employing a ‘defensive shield’ or armouring in anticipation of racist and discriminatory acts (Feagan & Sikes, 1994) and maintaining a level of high-effort coping in response to racial and social injustice (James, 1994).

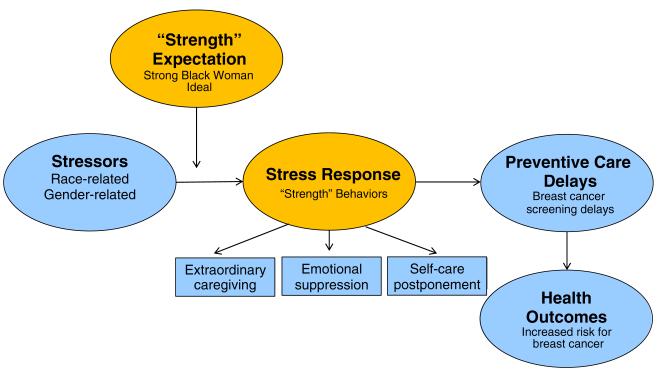

To frame the significance of gendered and cultural coping to observed delays in breast cancer screening, we draw on a framework informed by Black women’s voices of the experience of strong Black womanhood (Black & Peacock, 2011) the Stress and Strength Hypothesis (also referred to as the “strength hypothesis”). This gender-specific, culturally responsive stress-process framework explains the extent to which Black women’s primary, secondary and tertiary preventive healthcare behaviours (e.g. diet, exercise, screenings, and medical adherence/management) may be influenced by stress-reactive behaviours. Specifically, the strength hypothesis suggests that these stress reactions may be aligned with a ‘Strong Black Woman’ ideal in which Black women are expected to demonstrate resilience, self-reliance and psychological hardiness in the face of stressors and life demands. For women who adhere to this sociohistorical and cultural gender expectation of strength, ‘strength behaviours’ such as extraordinary caregiving, emotional suppression and delayed self-care may emerge. These strength behaviours may exhaust Black women’s personal resources for prioritizing or engaging in preventive care (i.e. diet, exercise, screenings and medical management). As a result, preventive care may be delayed, increasing the likelihood for chronic illness among Black women.

Although strength behaviours (e.g. extraordinary caregiving, emotional suppression and delayed self-care) may be observed in other groups of women (Jack, 1993; Jack & Ali, 2010; Hochschild & Machung, 1989; Newell, 1996; Shaevitz, 1984), it is important to note that for Black women, there may be distinct antecedents and characteristics that influence the manifestation of these behaviours (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). For instance, in an attempt to survive legalized slavery, Black women engaged in excessive caregiving, serving as mother and nurturer to their own children as well as ‘other-mother’ to children whose parents had been forcibly sold and separated (Mullings, 2002, 2005). Under these circumstances, the ability to suppress emotion while fulfilling the role of labourer and provider was vital to personal and familial protection. Since slavery, Black women have reclaimed strength in an attempt to separate representations of Black femininity and womanhood from existing negative stereotyping of Black women (e.g. Mammy, Jezebel and Welfare Queen) (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2005). When considered against a context of pervasive racial, gender and class discrimination that Black women are additionally expected to manage, functional alternatives to the Strong Black Woman role may appear to be limited.

Building upon sociological examinations of strength, investigations of the critical role of strength in Black women’s health and wellness are increasing, revealing associations with increased binge eating, anxious and depressive experiences, and obesity, among others (Amankwaa, 2003; Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2003, 2005, 2008; Black & Peacock, 2011; Edge & Rogers, 2005; Harrington, Crowther, & Shipherd, 2010; Harris-Lacewell, 2001; Woods-Giscombé, 2010; Woods-Giscombé & Black, 2010). Links between strength beliefs and behaviours and delays in Black women’s breast cancer screenings have yet to be made. The purpose of this paper is to examine how a Strong Black Woman ideal coupled with competing life demands and sociohistorical factors may result in health-compromising strength behaviours that explain delays in breast cancer screenings (Figure 1). We present findings from two distinct qualitative studies on stress and strength in Black women to highlight the critical links between stress in Black women’s lives and resultant behaviours that lead to breast cancer disparities.

Figure 1.

Stress and strength hypothesis

Methods

Data sources and methodology

To explore the potential implications of Black women’s stress responses to their breast cancer screening behaviours, we conducted a secondary analysis of three data sources that explored the significance of the concept of strength for Black women: (1) popular media (magazines targeting Black women); (2) social media (blogs written by and for Black women); and (3) focus groups (discussion groups exclusively composed of Black women). The popular and social media data are derived from the Strong Black Woman Script Study (Black & Peacock, 2011, PI), a research project that examined Black women’s perspectives on strength and health, and the focus group data are derived from the Superwoman Schema Study (Woods-Giscombé, 2010, PI), a research project that examined antecedents, characteristics and health outcomes of strength. The narratives analysed share a concept of strength, which we label strength behaviours (i.e. extraordinary caregiving, emotional suppression and self-care postponement) (Black & Peacock, 2011). In the current study, we analysed narratives previously coded to each strength behaviour and identified and categorized their relevance for explaining potential delays at three points of preventive breast care: (1) breast care priority; (2) scheduling and attending appointments; and (3) acknowledging breast symptoms. We also explored women’s insight on the race-related and gender-related stressors in their lives. A brief discussion of each data source follows, including details of the original data analyses.

Popular and social media

These sources present the culturally relevant and gender-specific contexts of Black women’s lives, through political narratives and reflections on family/intimate relationships, community, careers and health. Women’s perspectives on strong Black womanhood were explored, including its relevance to their health and wellness. To locate magazine articles, we entered the term ‘Strong Black Woman’ into EBSCOhost, Academic Search Premier and PsycINFO, producing 104 articles that included the term in the title or text. We further limited the search to magazines targeting Black women and that were published within a 10-year period (1996-2006) that also broadly corresponds with the introduction of strength-critical examinations of Black women’s health and lives (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2003, 2005, 2008; Harris-Lacewell, 2001; Mullings, 2002, 2005; Wyatt, 2008). Articles appearing as editorial responses, reader narratives and monthly columns were reviewed. Based on their substantive relevance to the targeted behaviours (e.g. role management, coping and self-care) frequently discussed in articles regarding strength and Black women (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2003, 2005, 2008; Harrington, Crowther, & Shipherd, 2010; Harris-Lacewell, 2001; Mullings, 2002, 2005), 20 articles were included in the final analysis. Similarly, the search term ‘Strong Black Woman’ was entered into a Google search to locate blogs written by and about Black women’s experiences with strength, producing 600 blog postings. The search was further refined by several criterion, including blogs appearing within 1 year of the date of search (November 2007-November 2008) and characteristics of blog visibility (number of blog postings in 1 year, number of blogs linked to the blog site, etc.). Blogs were reviewed in a sequential order until 10 were found that met the criteria. Content analysis of the blogs paralleled analysis of magazine articles, exploring links between strength and targeted behaviours. More complete details of the original criteria for data collection, qualitative methodology enlisted (ATLAS.ti Version 5.5.9; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and emergent themes explored can be found within the original manuscript (Black & Peacock, 2011).

Focus group data

Between December 2006 and June 2007, eight focus groups were conducted among a sociodemographically diverse population of African American women aged 19-72 years (median age, 29 years; average age, 34 years), living in the southeastern part of the United States. Focus group size ranged from 2 to 6; 48 women completed participation in the study. Participants came from a range of educational (from less than 12 years of education to terminal degrees such as PhD and JD) and professional backgrounds (e.g. unemployed and law school faculty). Regarding education, 18% did not complete high school; 10% completed high school only; 17% completed trade school, technical school, or an associate’s degree; 18.8% attended college but did not graduate; 17.4% graduated from a four-year university course; and 14.6% obtained a master’s or terminal professional degree. Most (64%) were employed, 40% were current students and 35% were not working. Sixty per cent were single; 10% were married; 15% were in a committed relationship; and 15% were divorced, separated or widowed. A majority (65%) were mothers. The median annual household income was between $26,000 and $50,000 (34% of the sample), and 41% of the sample earned less than $15,000 per year.

The focus groups explored the stress experiences of African American women and its relevance to a sociohistorical role of the Strong Black Woman or Superwoman. The focus group design was guided by the work of Kitzinger and Barbour (1999) and Morgan and Krueger (1998). This methodology identified the various dimensions of the Superwoman role in African American women as well as relevant contextual factors. Additionally, the focus groups provided a supportive environment for women to discuss sensitive issues related to experiencing and coping with stress (Jarrett, 1993). Focus groups were conducted by the PI of the study (an African American woman in her 30s). Example focus group questions included, ‘When I say the word stress, what does it mean for you?’ ‘How did you see the women (mothers, grandmothers) in your life cope with stress?’ ‘Have you ever heard the term Strong Black Woman/Black Superwoman?’ and ‘What are her characteristics?’ All focus group interviews were audiotaped and professionally transcribed. The author and the research assistant then compared the transcript with the audiotaped data to confirm accuracy. Data analysis began after the first focus group was completed and continued throughout the duration of the study. The results of the focus group data informed a conceptual framework of Black women’s stress experiences, the Superwoman Schema (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). Further details of the analyses and conceptual framework components can be reviewed in this publication.

Ethical approval

Institutional review board approval was not needed for the analysis of the popular and social media data because it is publicly accessible. The institutional review board of the sponsoring university for the focus group study approved the study methodology.

Results

To provide insight on how the role of strength can contribute to our understanding of breast cancer screening delays among Black women, we first established participants’ perspectives on the impact of unique race-related and gender-related stressors on their daily lives. These results are then followed by data that may further explain the impact of stress and strength behaviours on screening delays vis-à-vis breast care priority, scheduling and attending screening appointments, and acknowledging breast symptoms.

Race-related and gender-related stressors

Women’s perceptions of the stressors relevant to their lives were grounded in the reality of the discriminatory contexts in which they lived, as demonstrated in Ebony magazine,

We cannot minimize the impact of the environment that we live in and the consequences of those environments, whether they are low-income, upper-class, all-black, or a combination. These are unique stressors that we incur as minorities living in a dominant culture (Foston, 2005).

This sentiment was echoed by a focus group participant who suggested that the devaluing race-based perceptions from majority group members about African Americans impacted her stress load,

They’re all ready to write you off. They already tell you what you’re going to be. They already tell you how far you’re going to get in life. And so I felt like that added to a lot of stress, because I refuse to be another statistic.

Siddity, a blogger who wrote When a Black Woman Needs Help, explains how daily stress was exacerbated by Black women’s status as a double minority, ‘The lives of many of the black women I’ve known have been an intersection of the real axis of evil, racism and gender inequality.’ (Siddity, 2008). Germane to the challenge of being both Black and female living in a discriminatory society was recognizing society’s conflicting value of Black womanhood. As one journalist described it in Heart & Soul magazine, Black women feel devalued by society’s prevailing perception of femininity, ‘…the effects of living in a society that neither affirms nor reflects me, one where too often, Black women are regarded as beasts of burden, mammies, and martyrs.’ (Nelson, 1995). Conversely, the narrative in Heart & Soul magazine further illustrated how society’s regard for Black womanhood also translated into a rigid view of who Black women could be, ‘…born and raised to be self-sacrificing mainstays..a lifetime of conditioning…one of the few ways this society allows Black women to be powerful: as the Rock of Gibraltar.’ (Nelson, 1995).

Feelings of being devalued by society sometimes included internalizing stigma imposed by the dominant culture. A journalist in Ebony describes how internalized messages sometimes translated into a self-armouring process intended to protect one’s self-image and representation of one’s entire race.

We live in a society that is already inclined to think less of us, so once we make it into the big league, the last thing we want is to show a chink in the armor (Williams & Harrison, 2005).

Despite self-armouring, however, in Essence magazine’s article on Depression and the Superwoman, one journalist described how being faced with a multitude of stressors is perceived by many Black people as a normative function of daily living, ‘Black people expect to be in pain every day’ (Williams & Harrison, 2005).

Breast care priority

Self-care delays

Prioritizing breast care amidst stressors and among women who embody a self-sacrificial form of strength to combat stressors may prove challenging. As suggested in Heart & Soul magazine, excluding self-care is an assumed role of the Strong Black Woman:

we see ourselves not just as superwoman but as having no choice. The idea of self-neglect is a historical one, because there was never the luxury to stop, sit down, and take care of ourselves (Nelson, 1995).

On the basis of this belief of strong Black womanhood, the importance of breast health may pale in comparison with caregiving responsibilities and ensuring familial survival in an unjust world. Further, preventive breast health may not be on the woman’s radar whose self-care is often last on the list, as demonstrated by this focus group participant, ‘my life is tied around everybody else and as far as myself I just forget about myself and no, I don’t take care of myself like I should’. Hence, screening delays could be easily attributable to the cultural shift required to simply claim time for self as a routine practice.

Scheduling and attending screening appointments

Extraordinary caregiving

Engaging in extraordinary caregiving may delay women’s scheduling or attending screening appointments. Extraordinary caregiving is qualified by the extent to which women believed and endorsed expectations for a Strong Black Woman caregiver to meet the needs of immediate family, fictive kin, community members and beyond. This mode of caregiving was often demonstrated and observed across generations, conveying the extent to which women reacted to life stressors through height-ened caregiving. A blogger states,

as black women we are supposed to be all things to everybody cause that’s how our mama’s did it, our grandmama’s did it, they mama’s did it…that’s how we survived through slavery, brutal rapes..and just regular day to day living (Siddity, 2008).

Self-reliant characteristics are also indicative of this mode of caregiving. Often, women moved through life believing that delegating tasks or requesting help was unnecessary. A focus group participant shares her challenges,

my co-workers get on me all the time, my significant other gets on me all the time, about slowing down, and I haven’t managed that because I feel like I can do everything.

Functioning in this capacity often promoted exhaustion and left women with little time to tend to personal responsibilities and obligations. With a strength protocol guiding their daily life management, competing demands and responsibilities may take priority over scheduling a mammogram or attending a scheduled mammogram, increasing the risk for screening delays.

Acknowledging breast symptoms

Emotional suppression

Women across data sources expressed an awareness of emotional invulnerability—even being emotionally impermeable—as critical to demonstrating strength within their families and communities. A focus group participant shares, ‘So like when I need to talk to somebody about something, I don’t..it’s like I hold a lot of stuff inside me and I never ever let it out’. In other cases, displaying emotional pain or distress proved costly to the image of Black womanhood, as revealed by a blogger

we are told we can’t cry, we can’t feel pain, we can’t break down. And those individuals that dare to crack the façade of indomitable black womanhood are ridiculed. They are told to get it together (Siddity, 2008).

The emotional silencing required to maintain emotional stoicism could encourage denial of physical breast symptoms as well. It seems plausible that repressing emotion—either from mental or physical distress— jeopardizes women’s timely acknowledgement of compromised breast health. As a result of this delay, by the time women who endorse strength reveal the condition of their breast health, they could also be increasing their risk for late-stage diagnosis at first detection.

Discussion

In the present study, we applied the Stress and Strength Hypothesis to examine how Black women’s stress reactions could explain the observed delays in their breast cancer screenings. That reacting to race-related and gender-related stressors incited strength behaviors such as extraordinary caregiving, emotional suppression and delayed self-care; and preventive breast health behaviours such as breast care priority, scheduling and screening appointments, and acknowledging breast symptoms could be impacted. Examinations of this type are critical given that Black women have the highest mortality rates from breast cancer-related deaths across any stage and at any age (American Cancer Society, 2009). Although reports establishing explanations for Black women’s poor breast health are increasing, additional evidence is needed to establish how the social and cultural contexts of Black women’s lives contribute to delays in breast cancer screenings. We addressed this gap by incorporating the strength hypothesis to highlight the gendered and cultural components of Black women’s coping behaviours and the pathways through which these behaviours have the potential to impact screening behaviours.

Focusing on Black women’s reactions to stressful situations as a potential barrier to screening extends thematic studies of stress and breast cancer, which include stressors as barriers to screening, increased stress as a result of breast cancer scare or diagnosis and physiological risk factors of stress for breast cancer occurrence. Our examination suggests that Black women’s stress-coping behaviours are reflective of both fight-or-flight and tend-and-befriend. The former is akin to the emotional distancing and suppression strong Black women endorsed as a reaction to stressors. The latter is demonstrated through heightened caregiving in the face of distress. Perhaps, the mechanism ‘strive to survive’ might best describe the sociohistorical and cultural stress reactions used by black women who endorse strength: women may strive for self-reliance and psychological hardiness in an attempt to survive stressors that are largely out of their control. In so doing, other critical health-promoting behaviours, breast cancer screening, for example, may be influenced. Future examinations of Black women’s preventive care delays should consider the implications of the stress and strength paradigm.

Limitations and implications for research and clinical practice

Although this paper identifies potential links between stress, strength and Black women’s breast cancer screening behaviours, data came from Black women in the general population. Future research including qualitative and quantitative data on these topics from Black women who have currently or have previously experienced breast cancer will help confirm these hypothesized associations. In addition, research could be conducted with Black women in the recommended breast cancer screening age bracket to determine how strength characteristics and behaviours influence adherence to screening guide-lines. If additional evidence from these studies suggests significant links between strength and screening behaviours, future research could be conducted to examine relevant interventions.

Expanded research in this area could also inform clinical practice vis-à-vis ‘personalized prevention’ and ‘personalized medicine’ in women’s health: comprehensive health promotion and care that takes into account individual biological characteristics and social and cultural influences (ORWH, 2010). The full continuum of breast cancer care—from prevention and screening through detection, diagnosis, treatment and survivorship—represents areas of critical need for such tailored approaches for Black women. The strength hypothesis offers guidance to health professionals seeking to increase the adoption of critical breast health behaviours among Black women through the inclusion of gender-specific and culturally responsive approaches.

For example, proper diet and exercise represents a path of primary prevention for breast cancer (American Cancer Society, 2009). However, compromised self-care, sedentary behaviours and emotional eating have been reported as stress-reactive strength behaviors among Black women (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2003; Black & Peacock, 2011; Woods-Giscombé, 2010; Woods-Giscombé & Black, 2010). An existing initiative through which timely self-care behaviours could be reinforced among Black women is the patient-centred medical homes approach (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2011). Although developed to increase quality primary care for children and adults, family-centred patient-centred medical homes also offer a unique opportunity for community health workers (CHWs) to emphasize preventive care for Black women at general population risk of developing breast cancer. Specifically, CHWs could educate Black mothers on child health and nutrition while co-educating and supporting their awareness of links between proper diet, exercise and their own breast health. Additionally, CHWs equipped with the knowledge of stress-reactive strength behaviours such as delayed self-care might offset stressor impact by offering culturally relevant stress management techniques (Woods-Giscombé & Black, 2010).

The association between emotional suppression, psychological distress and breast cancer diagnosis and treatment has been well documented (Iwamitsu et al., 2005; Schlatter & Cameron, 2010). Results indicate that women who respond to breast cancer diagnosis and treatment through emotional expressiveness tend to experience less distress and improved recovery. Unlike ‘Type C’ individuals (Temoshok, 1987) who internalize emotions because they may feel helpless or hopeless in the face of a breast cancer scare, Black women who embody strength may presume that strong women should manage their personal stressors and life demands in silence, hence holding the belief that strong Black women cannot be overwhelmed by a health scare. Mental health professionals offering psychological support after a diagnosis or treatment may encourage strength-identified women to recognize the beneficial aspects of sharing their distress during breast health episodes including the courageous attributes of emotional expressiveness, the potential admiration garnered from other women who may be suffering in silence and the links to enhanced recovery.

Additional consideration should be given to how stress-reactive strength behaviours such as excessive caregiving could serve as a barrier to post-treatment recovery and care by leaving little time for the extra commitment of a support group. The Patient Navigation Research Program, a five-year, $25 million, multi-site study funded by the National Cancer Institute, could equip breast cancer navigators with psychoeducational strategies that redefine the role of strength in caregiving through healthful behaviours such as task delegation and boundary setting. To this end, breast cancer navigators who are attempting to facilitate Black women’s entry to support groups for survivors might highlight the assets of ‘saying no’ and locating additional sources of help for role responsibilities in an attempt to redirect attention to self-care after treatment, in turn, enhancing breast cancer survival and offering a health-promoting model of strength. In sum, the strategies presented here may assist in reducing Black women’s mortality rates as a result of compromised breast health care.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by the National Institute of Health, the Office of Research on Women’s Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant number K12HD055892).

REFERENCES

- Amankwaa LC. Postpartum depression among African-American women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2003;24:297–316. doi: 10.1080/01612840305283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society . Breast cancer facts & figures 2009-2010. American Cancer Society, Inc; Atlanta: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda MP, Knight BG. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. The Gerontologist. 1997;37:342–354. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T. Strong And large black women?: Exploring relationships between deviant womanhood and weight. Gender and Society. 2003;17(1):111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T. Keeping up appearances, getting fed up: The embodiment of strength among African American women. Meridians: Feminism, Race, Ttransnationalism. 2005;5(2):104–123. [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T. Listening past the lies that make us sick: A voice-centered analysis of strength and depression among black women. Qualitative Sociology. 2008;31(4):391–406. [Google Scholar]

- Black AR, Peacock N. Pleasing the masses: Messages for daily life management in African American women’s popular media sources. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(1):144–150. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow AJ, Swiecicki P, Haan P, Osuch JR, Symonds LL, Smith SS, Boivin MJ. The emotional journey of women experiencing a breast abnormality. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21(10):1316–1334. doi: 10.1177/1049732311405798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantley PJ, O’Hea EL, Jones G, Mehan DJ. The influence of income level and ethnicity on coping strategies. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2002;24:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JB. Breast cancer race, ethnicity, and survival: A literature review. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2002;74(2):187–192. doi: 10.1023/a:1016178415129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon WB. Organization for physiological homeostasis. Physiological Reviews. 1929;9:399–431. [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2008;5(8):466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway-Phillips R, Millon-Underwood S. Breast cancer screening behaviors of African American women: A comprehensive review, analysis, and critique of nursing research. The ABNF Journal. 2009;20(4):97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley A, Jennings J, Beckett JO, Leashore BR. Effective coping strategies of African Americans. Social Work. 1995;40:240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Duijts S. F. a., Zeegers M. P. a., Borne BV. The association between stressful life events and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Cancer. 2003;107(6):1023–1029. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge D, Rogers A. Dealing with it: Black Caribbean women’s response to adversity and psychological distress associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and early motherhood. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.047. 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagan JR, Sikes MP. Living with racism: The black middle-class experience. Beacon Press Books; Boston: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Foston N. How to look better, feel better, and live longer. Ebony. 2005;60(8):136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Frisby CM. Messages of hope: Health communication strategies that address barriers preventing Black women from screening for breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;32(5):489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Gerend M. a., Pai M. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: A review. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17(11):2913–2923. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullatte MM, Brawley O, Kinney A, Powe B, Mooney K. Religiosity, spirituality, and cancer fatalism beliefs on delay in breast cancer diagnosis in African American women. Journal of Religion and Health. 2010;49(1):62–72. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington EF, Crowther JH, Shipherd JC. Trauma, binge eating, and the “strong Black woman”. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(4):469–479. doi: 10.1037/a0019174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Lacewell M. No place to rest: African American political attitudes and the myth of black women’s strength. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy. 2001;23(3):1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hilakivi-Clarke L, Rowland J, Clarke R, Lippman ME. Psychosocial factors in the development and progression of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 1994;29(2):141–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00665676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A, Machung A. The second shift. Penguin Groups; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamitsu Y, Shimoda K, Abe H, Tani T, Okawa M, Buck R. Anxiety, emotional suppression, and psychological distress before and after breast cancer diagnosis. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(1):19–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack D. Silencing the self: Women and depression. Harper Collins; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jack D, Ali A. Silencing the self across cultures: Depression and gender in the social world. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- James SA. John Henryism and the health of African-Americans. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1994;18(2):163–182. doi: 10.1007/BF01379448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett RL. Focus group interviewing with low-income minority populations: A research experience. In: Morgan DL, editor. Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 184–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger J, Barbour RS. Developing focus group research: Politics, theory, and practice. Sage; London: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Mujahid M, Schwartz K, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Salem B, Katz SJ. The influence of race, ethnicity, and individual socieconomic factors on breast cancer stage at diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(12):2173–2178. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillberg K. Stressful life events and risk of breast cancer in 10,808 women: A cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157(5):415–423. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL, Krueger RA. The focus group kit. Volumes 1-6 (box set) Sage; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mullings L. The sojourner syndrome: Race, class, and gender in health and illness. Voices. 2002;6(1):32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mullings L. Resistance and resilience: The sojourner syndrome and the social context of reproduction in central Harlem. Transforming Anthropology. 2005;13(2):79–91. [Google Scholar]

- National Committee for Quality Assurance NCQA patient-centered medical home 2011: Health care that revolves around you. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.ncqa.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=ycS4coFOGnw%3d&tabid=631.

- Nelson J. Beyond the myth of the strong black woman. Heart & Soul. 1995;8:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Newell S. The superwoman syndrome: A comparison of the “heroine” in Denmark and the UK. Women in Management Review. 1996;11(5):36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Research on Women’s Health Moving into the future with new dimensions and strategies: A visions for 2020 for women’s health research. 2010 Retrieved from http://orwh.od.nih.gov/research/strategicplan/ORWH_StrategicPlan2020_Vol1.pdf.

- Peek ME, Sayad JV, Markwardt R. Fear, fatalism and breast cancer screening in low-income African-American women: The role of clinicians and the health care system. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(11):1847–1853. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0756-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlatter MC, Cameron LD. Emotional suppression tendencies as predictors of symptoms, mood, and coping appraisals during AC chemotherapy for breast cancer treatment. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(1):15–29. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddity [Accessed October 10, 2010];When a black woman needs help. 2008 Jun 20; 2008. Retrieved from http://siditty.blogspot.com/2008/06/when-black-woman-needs-help.html.

- Shaevitz HM. The superwoman syndrome. Warner Books; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Stead LA, Lash TL, Sobieraj JR, Chi DD, Westrup JL, Charlot M, Rosenberg CL. Triple-negative breast cancers are increased in black women regardless of age or body mass index. Breast Cancer Research. 2009;11:R18. doi: 10.1186/bcr2242. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2688946/pdf/bcr2242.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung R. a. R., Updegraff J. a. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review. 2000;107(3):411–429. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.107.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temoshok L. Personality, coping style, emotion and cancer: Towards an integrative model. Cancer Surveys. 1987;6:545–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services Obesity and African Americans. 2009 Retrieved from http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/content.aspx?ID1/46456.

- Woods-Giscombé C. Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20(5) doi: 10.1177/1049732310361892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé C, Black AR. Mind-body interventions to reduce risk for health disparities related to stress and strength among African American women: The potential of mindfulness-based stress reduction, loving-kindness, and the NTU therapeutic framework. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2010;15(3):115–131. doi: 10.1177/1533210110386776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TW, Harrison GL. Depression and the superwoman. Essence (Downsview) 2005;36(2):152–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt J. Patricia Hill Collins’s black sexual politics and the genealogy of the strong Black woman. Studies in Gender and Sexuality. 2008;9(1):52–67. [Google Scholar]