Abstract

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR) is the target of the statins, important drugs that lower blood cholesterol levels and treat cardiovascular disease. Consequently, the regulation of HMGCR has been investigated in detail. However, this enzyme acts very early in the cholesterol synthesis pathway, with ∼20 subsequent enzymes needed to produce cholesterol. How they are regulated is largely unexplored territory, but there is growing evidence that enzymes beyond HMGCR serve as flux-controlling points. Here, we introduce some of the known regulatory mechanisms affecting enzymes beyond HMGCR and highlight the need to further investigate their control.

Keywords: Cholesterol, Cholesterol Regulation, ER-associated Degradation, Post-translational Modification, Sterol, NSDHL, SREBP, Squalene Monooxygenase

Why Look beyond 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase?

Eighty years ago, The Journal of Biological Chemistry published one of the first examples of feedback control. Schoenheimer and Breusch (1) found that mice that were fed cholesterol synthesized less of it. Subsequently, much has been published on this complex molecule, which continues to fascinate. Strict control of cholesterol synthesis is necessary because it is energetically expensive to make and is toxic in excess but is essential for metazoan life. The cholesterol synthesis or mevalonate pathway was elucidated thanks to the pioneering work of many researchers, including Popják, Cornforth, Kandutsch, and, of course, Konrad Bloch, who had worked with Schoenheimer and received a Nobel Prize for his elegant studies on cholesterol synthesis (2). However, of the >20 enzymes involved, most attention has focused on just one: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR).2

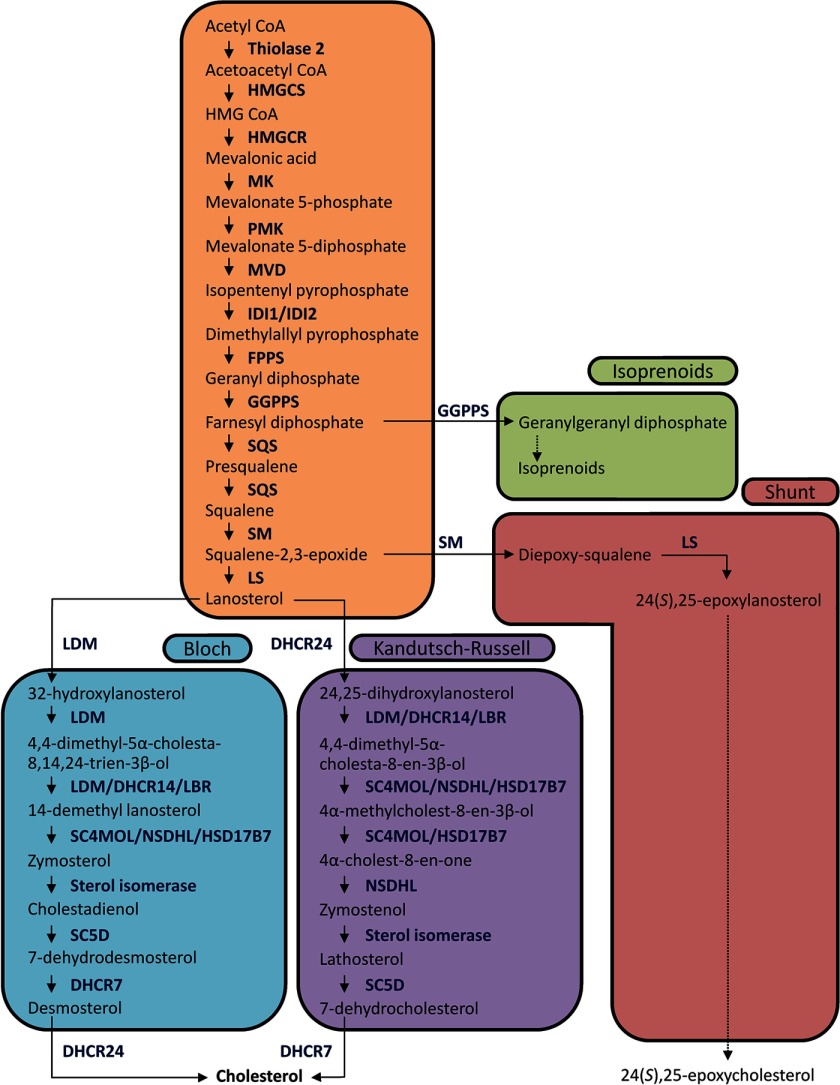

The third step in the mevalonate pathway (Fig. 1), catalyzed by HMGCR, is generally regarded as the rate-limiting step in cholesterol synthesis. As the target of the statins, the “go to” drugs for treating high cholesterol levels and cardiovascular disease, there has been an understandable concentration of effort on unraveling the regulation of HMGCR (reviewed in Refs. 3 and 4). However, a generally accepted biochemical principle is that biosynthesis pathways have multiple control points (5). HMGCR occurs before a branch point directing flux to sterols or isoprenoids (Fig. 1), and ablation of its activity can have dire consequences, as illustrated by knock-out of hepatic HMGCR being lethal to mice (6). Furthermore, over the last couple of decades, discovery and characterization of inborn errors of cholesterol synthesis have not only emphasized the importance of cholesterol but have also drawn attention to the post-HMGCR pathway: how these genetic diseases manifest is likely due to accumulation of intermediates and not solely due to a lack of cholesterol synthesis (reviewed in Ref. 7).

FIGURE 1.

Cholesterol synthesis pathway. The mevalonate pathway leads to lanosterol, which can then be diverted into either the Bloch pathway, producing cholesterol via desmosterol, or the Kandutsch-Russell pathway, via 7-dehydrocholesterol. Two other branches also diverge from the mevalonate pathway. Isoprenoids are produced by geranylgeranyl-diphosphate synthase (GGPPS) acting twice to convert farnesyl diphosphate to geranylgeranyl diphosphate, and flux through the shunt pathway occurs when SM acts twice to convert squalene 2,3-epoxide into diepoxysqualene, eventually leading to the production of 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol. Intermediates and enzymes in this shunt pathway are not yet fully elucidated (75) but are presumed to follow the Kandutsch-Russell pathway. MK, mevalonate kinase; PMK, phosphomevalonate kinase; MVD, diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase; FPPS, farnesyl-pyrophosphate synthase; SQS, squalene synthase; LDM, lanosterol 14α-demethylase; SC5D, sterol C5-desaturase.

Intermediates in Cholesterol Synthesis as Physiological Regulators

There is a growing list of intermediates in cholesterol synthesis, mostly sterols, which have been credited with having regulatory functions distinct from those of cholesterol. An example is 7-dehydrocholesterol, which is converted to cholesterol by DHCR7 (7-dehydrocholesterol reductase) but is also a precursor for vitamin D, involved in bone growth. Hence, polymorphisms in the DHCR7 gene are determinants of vitamin D status (8). Mutations in DHCR7 cause the most common inborn error of cholesterol synthesis, called Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, manifested by devastating developmental abnormalities. The higher prevalence of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome in Northern European populations may be explained by the heterozygote advantage, as an accumulation of 7-dehydrocholesterol leads to increased capacity to produce vitamin D even with reduced exposure to sunlight (7).

C4-methylsterols are produced by lanosterol 14α-demethylase (encoded by CYP51A1 (cytochrome P450, family 51, subfamily A, polypeptide 1)) and demethylated by SC4MOL (sterol-C4-methyl oxidase-like 1; methylsterol monooxygenase 1) and its partner, NSDHL (NAD(P)-dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like; sterol-4-α-carboxylate 3-dehydrogenase, decarboxylating). They are also referred to as meiosis-activating sterols (MASs), occurring at high concentrations in the testis and ovary, and as the name suggests, they play an important role in meiosis activation. Apparently, MASs are active in the skin as well because skin abnormalities are caused by perturbations of cholesterol synthesis in humans and in animal models at several points, including at SC4MOL and NSDHL (e.g. Ref. 9). The EGF receptor (EGFR) may be pivotal in these skin changes, as similarities are observed in mice and humans with EGFR pathway perturbations. Moreover, accumulation of MASs through inactivation of SC4MOL and NSDHL reduces EGFR expression and signaling (10).

Another intermediate that has specific functions not shared by cholesterol is 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, which is purportedly the primary degradation signal for HMGCR (11, 12). The earlier non-sterol intermediate squalene has also been implicated in stimulating HMGCR degradation (13). A number of cholesterol synthesis intermediates can serve as activating ligands of the nuclear liver X receptor (LXR), which up-regulates cholesterol export genes and represses inflammatory genes. These sterols include 24,25-dihydrolanosterol (14), MASs (9), and desmosterol (15, 16). Accumulating in macrophage foam cells in a regulated fashion, desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses by activating LXR (16).

The oxysterol 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol (24,25-EC) is the most abundant LXR ligand in the developing mouse midbrain, where it promotes dopaminergic differentiation of embryonic stem cells (16). Known as a particularly potent LXR agonist (17), 24,25-EC is produced in a shunt pathway in sterol synthesis (18), and its production is determined by the relative activities of squalene monooxygenase (SM) and lanosterol synthase (LS) (Fig. 1). Partial inhibition or knockdown of LS diverts more flux into the shunt pathway, producing more 24,25-EC (19), whereas overexpression of LS abolishes 24,25-EC production (20). Conversely, overexpression of SM increases 24,25-EC production (21). The extent to which SM and LS are differentially regulated to alter 24,25-EC production is currently not known.

Therefore, various sterols serving as physiological modulators can accumulate in a regulated manner, suggesting in turn that the enzymes that form and transform them are also regulated. Indeed, there is growing evidence that other enzymes beyond HMGCR are flux-controlling points. Regulation of cholesterol synthesis can occur at multiple levels throughout the pathway. We will illustrate these with recent work on post-HMGCR enzymes.

Transcriptional Regulation

Sterol Regulatory Element-binding Proteins (SREBPs)

The SREBP family of transcription factors is activated in response to low sterol status and helps coordinate the cholesterol synthesis pathway (22). Thus, nearly all of the genes encoding cholesterol synthesis enzymes are SREBP targets (Table 1). A notable exception is the lamin B receptor (LBR), a protein of the inner nuclear membrane involved mainly in heterochromatin organization but also possessing sterol Δ14-reductase activity (23). The principal sterol Δ14-reductase, located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), is DHCR14, encoded by the TM7SF2 (transmembrane 7 superfamily member 2) gene. However, LBR appears to adequately compensate, as cholesterol levels are normal in Tm7sf2 knock-out mice (24). Because TM7SF2 is an SREBP-2 target gene, whereas LBR is not (23), it may be that LBR is constitutive, whereas TM7SF2 encodes the inducible sterol Δ14-reductase activity.

TABLE 1.

SREBP regulation of cholesterol synthesis enzymes

| Gene name (HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee) and gene symbol | SREBP target?a | SRE(s) mapped?b | SRE sequence (human) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, cytosolic,c ACAT2 | Yes | No | |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1 (soluble), HMGCS1 | Yes | Yes (30) | G CCAC C TCAC, C TCAC A CCAC |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, HMGCR | Yes | Hamster (79) | |

| Mevalonate kinase, MVK | Yes | No | |

| Phosphomevalonate kinase, PMVK | Yes | No | |

| Mevalonate (diphospho)decarboxylase, MVD | Yes | No | |

| Isopentenyl-diphosphate Δ-isomerase 1/2, IDI1/IDI2 | Yes | No | |

| Farnesyl-diphosphate synthase, FDPS | Yes | Yes (80) | C TCAC A CGAC |

| Geranylgeranyl-diphosphate synthase 1,GGPS1 | Yes | No | |

| Farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1, FDFT1 | Yes | Yes (29) | C TCAC A CTAG, A TCAC G CCAG |

| Squalene epoxidase, SQLE | Yes | Yes (27) | A CCAC G CAAC |

| Lanosterol synthase (2,3-oxidosqualene-lanosterol cyclase), LSS | Yes | No | |

| Cytochrome P450, family 51, subfamily A, polypeptide 1, CYP51A1 | Yes | Yes (81) | A TCAC C TCAG |

| Transmembrane 7 superfamily member 2, TM7SF2 | Yes | Yes (82) | GCCCAGCATGGGd |

| Lamin B receptor, LBR | No | NAe | |

| Methylsterol monooxygenase 1, SC4MOL | Yes | No | |

| NAD(P)-dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like, NSDHL | Yes | No | |

| Hydroxysteroid 17β-dehydrogenase 7, HSD17B7 | Yes | Yes (83) | C TCAC C CGAC |

| Emopamil-binding protein (sterol isomerase), EBP | Yes | Yes (84) | TGGCGCCACGd |

| Sterol C5-desaturase, SC5D | Yes | No | |

| 7-Dehydrocholesterol reductase, DHCR7 | Yes | Rat (85) | |

| 24-Dehydrocholesterol reductase, DHCR24 | Yes | Yes (26) | A TCGG A CCAG, C TCGG C CCAC |

a Ref. 22 shows in mice that all genes listed are SREBP targets, except for GGPS1, which was shown in Ref. 86; EBP, which was shown in Ref. 84; and LBR, which is not regulated by SREBP (23).

b This is to the best of our knowledge; the data refer to human promoters.

c This is also known as thiolase 2.

d This does not appear to be a classical SRE and has not been included in the matrix used to derive Fig. 2.

e NA, not applicable.

Three isoforms of SREBP exist, with the SREBP-2 isoform being ascribed the major role in regulating cholesterol synthetic genes. A genome-wide ChIP-seq analysis of mouse liver determined that most of the sterol regulatory elements (SREs) that SREBP-2 binds to are within the proximal 2 kb of transcriptional start sites (25). We found very similar SRE consensus sequences between genes encoding cholesterol synthesis enzymes and other SREBP targets, with an apparently critical cytosine in the third position (Fig. 2). However, SREs have been mapped only for less than half of the human genes encoding cholesterol synthesis enzymes (9 of 21 that are SREBP target genes) (Table 1). These may not necessarily be conserved between mammalian species, considering that the SRE motif derived from murine ChIP-seq data (25) is very different from the SRE motif we found based on an array of known SREBP-2 target genes (26). This has been demonstrated for SQLE, where the reported SRE in the human promoter (27) is nonfunctional in the murine promoter (28).

FIGURE 2.

SRE consensus sequences. SREs from either seven cholesterol synthesis genes (A) or 11 other non-cholesterogenic SREBP targets (B) were used to create a consensus sequence with WebLogo 3.3. This figure was modified from Ref. 26.

The SREBP transcription factors are relatively weak activators of gene expression alone and commonly require the cooperation of other cofactors. For example, nuclear factor Y (NF-Y), which binds to CCAAT boxes, frequently binds to sites close to SREs (e.g. Refs. 26, 29, and 30). In fact, the spacing between SREs and NF-Y factors is crucial, with the highest efficiency observed when they are 16–20 bp apart (30). If this spacing is reduced to 14 bp, no gene activation is observed. Furthermore, Sp1 may also require specific spatial arrangements to regulate SREBP genes: a 10-bp separation resulted in activation, but inserting 4 or 10 bp more ablated this (31). These findings indicate that the spatial distance, but not the helical phase, are important for other transcription factors to regulate SREBP genes along with SRE sites.

Just as Sp1 and NF-Y can activate transcription synergistically with SREBPs, so too can dual SREs occurring in the same promoter. Thus, two closely spaced SREs work cooperatively to activate transcription of FDFT1 (farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1; encoding squalene synthase) and DHCR24 and may be a mechanism for energy conservation. Because cholesterol synthesis is an energetically expensive process, cooperativity would ensure that key genes must be strongly activated to commit to cholesterol synthesis (26).

Other Factors

Besides SREBP, numerous other transcription factors have been implicated in the transcriptional control of the various enzymes in cholesterol synthesis. LXR has been reported to regulate cholesterol biosynthesis by directly silencing the gene expression of two cholesterogenic enzymes (FDFT1 and CYP51A1) (32). This finding fits in with the known propensity of LXR to reduce cholesterol status. However, LXR has also been reported to up-regulate gene expression of one of the final enzymes in cholesterol synthesis, DHCR24 (33), but a subsequent study was unable to confirm this (26). Significantly, LXR agonists are not noted as affecting cholesterol synthesis (e.g. Ref. 34). Growth factors involving signaling via the androgen receptor or Akt can also up-regulate cholesterogenic genes, but this occurs indirectly, through activation of SREBP-2 (35, 36).

MicroRNAs and Alternative Splicing

The discovery of ubiquitous microRNAs (miRNAs) has added yet another layer of complexity to the regulation of gene expression. Perhaps the best studied in the context of cholesterol metabolism is miR-33, an intronic miRNA encoded in the SREBP genes. miR-33 controls cellular cholesterol export, whereas its SREBP host genes stimulate cholesterol synthesis (reviewed in Ref. 37). However, overall, relatively little has been reported on miRNAs in the context of cholesterol synthesis. miR-122, the most abundant miRNA in the liver, decreases expression of many cholesterol synthetic genes, although the effects appear to be indirect (38, 39).

Alternative splicing is a generalized phenomenon, with nearly all multi-exonic genes subject to alternative splicing (40). When transcripts with biological functions are created, the alternative splicing is considered productive. An alternative transcript of HMGCR in which exon 13 is skipped can be considered unproductive in that the protein encoded by this shorter transcript is inactive. Importantly, this alternative splicing is regulated by sterols, with proportionally less of the unproductive transcript present when sterol levels are low and more when sterol levels are higher (41). This effect also extends to other cholesterogenic genes, including HMGCS1 (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1, soluble) and MVK (mevalonate kinase) (41). Because the effect is mediated via SREBP-2 and alternative transcripts occur for all cholesterol synthesis enzymes beyond HMGCR (42), this effect is likely to involve the entire cholesterol synthesis pathway. Therefore, alternative splicing represents another layer of regulation and may even account for some of the altered cell localization of certain enzymes observed (see “Localization and Redistribution of Cholesterogenic Enzymes” below).

Post-translational Regulation

Regulated Turnover

The cholesterol synthesis pathway can be switched off rapidly (within 1 h), but transcriptional down-regulation via the SREBP pathway is relatively slow, with mRNA of target genes decreasing only after several hours. Thus, there must be mechanisms other than transcriptional regulation to account for this. Rapid shutdown of cholesterol synthesis requires post-transcriptional control, such as the extensively studied ER-associated degradation of HMGCR (reviewed in Refs. 3 and 4). Turnover of HMGCR is accelerated by non-sterol and sterol products of the mevalonate pathway (43), with physiological sterol degradation signals, such as 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, and side chain oxysterols, such as 24,25-EC and 27-hydroxycholesterol (generated from cholesterol itself) (12, 44). The regulated turnover is proteasomal and requires the Insig proteins, which also act to suppress SREBP activation (3, 4). Regulated ER-associated degradation also occurs for a later step in cholesterol synthesis, catalyzed by SM, albeit by a distinct mechanism from HMGCR.

Although not widely appreciated, SM has been proposed as a second rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis (45, 46). We found that cholesterol itself accelerates SM degradation, an example of end product inhibition (47). Also, unlike HMGCR, SM turnover does not require the Insig proteins. The precise molecular mechanism by which cholesterol accelerates proteasomal degradation of SM still needs to be defined, but it appears that cholesterol can bind directly to SM (48), as well as alter properties of the ER membrane (49). Regulated degradation of SM is mediated by a membrane-bound N-terminal domain, representing just 17% of the protein and separate from the catalytic domain. Notably, this regulatory domain is absent in lower organisms, including yeast, suggesting that this mechanism may signify a refinement of sterol homeostasis as birds and mammals evolved. A possible advantage of evolving a post-HMGCR step capable of rapid post-translational regulation in response to high cholesterol levels is that it would enable synthesis of important isoprenoids to continue while shutting down cholesterol synthesis (47). It is likely that regulated ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation occurs for other cholesterogenic enzymes, considering that data from large-scale proteomic screens indicate multiple ubiquitination sites on the majority of post-HMGCR enzymes (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Post-translational modifications on cholesterol synthesis enzymes

PhosphoSitePlus (53), a curated database of post-translational modification sites, was used to identify modified sites on human cholesterol synthesis enzymes that have been published. Sites in boldface indicate that the reference looked specifically at this protein and modification.

| Protein symbol | Protein name (UniProt) and gene symbol | EC | Phosphorylation (human, unless otherwise indicated)a | Acetylation (human)a | Ubiquitination (human)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiolase 2 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, cytosolic, ACAT2 | 2.3.1.9 | Ser-5, Ser-12 | Lys-200, Lys-233, Lys-235 | Lys-235 |

| HMGCS | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, cytoplasmic, HMGCS1 | 2.3.3.10 | Ser-4, Thr-476, Ser-486, Ser-49516; by Cdk1, Ser-5167 | Lys-46, Lys-246, Lys-273, Lys-321 | Lys-46, Lys-291, Lys-317, Lys-321,2 Lys-100, Lys-206, Lys-330, Lys-428, Lys-498, Lys-246, Lys-273, Lys-400, Lys-409 |

| HMGCR | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, HMGCR | 1.1.1.34 | Ser-872 (found in rodents 50)7 | Lys-248 (51), Lys-142, Lys-460, Lys-480,2 Lys-248, Lys-381, Lys-474, Lys-502, Lys-288, Lys-299, Lys-351, Lys-362, Lys-396, Lys-401, Lys-619, Lys-633, Lys-637, Lys-662, Lys-666, Lys-692, Lys-704 | |

| MK | Mevalonate kinase, MVK | 2.7.1.36 | |||

| PMK | Phosphomevalonate kinase, PMVK | 2.7.4.2 | Ser-15 | Lys-17, Lys-22, Lys-48, Lys-692 | |

| MVD | Diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase, MVD | 4.1.1.33 | Thr-50, Ser-96,4 Thr-209, Ser-211, Thr-212, Thr-221, Ser-222 | Lys-58, Lys-179 | |

| IDI1/IDI2 | Isopentenyl-diphosphate Δ-isomerase 1/2, IDI1/IDI2 | 5.3.3.2 | Thr-203 | Lys-176 | Lys-47, Lys-169, Lys-180, Lys-192, Lys-223, Lys-1132 |

| FPPS | Farnesyl-pyrophosphate synthase, FDPS | 2.5.1.10, 2.5.1.1 | Lys-123,2 Lys-353 | Lys-210, Lys-359, Lys-3532 | |

| GGPPS | Geranylgeranyl-pyrophosphate synthase, GGPS1 | 2.5.1.1, 2.5.1.10, 2.5.1.29 | Ser-60, Ser-70, Ser-87, Ser-91, Tyr-94 | Lys-25 | Lys-17, Lys-113, Lys-196 |

| SQS | Squalene synthase, FDFT1 | 2.5.1.21 | Lys-92, Lys-160, Lys-318, Lys-358, Lys-2132 | ||

| SM | Squalene monooxygenase, SQLE | 1.14.13.132 | Lys-290,2 Lys-426 | ||

| LS | Lanosterol synthase, LSS | 5.4.99.7 | Ser-334, Thr-475 | Lys-15, Lys-61, Lys-65, Lys-318, Lys-331, Lys-506, Lys-4323 | |

| LDM | Lanosterol 14α-demethylase, CYP51A1 | 1.14.13.70 | Ser-18 | Lys-97, Lys-127, Lys-162, Lys-183, Lys-186, Lys-219, Lys-348, Lys-364, Lys-418, Lys-147, Lys-442,3 Lys-166, Lys-267, Lys-2722 | |

| DHCR14 | Δ14-Sterol reductase, TM7SF2 | 1.3.1.70 | |||

| LBR | Lamin B receptor, LBR | 1.3.1.70 | Ser-71 by Cdc2 kinase (52); Ser-67, Ser-84, Ser-86,2 Ser-97,5 Ser-99,6 Thr-118,3 Ser-128 | Lys-55, Lys-190, Lys-594, Lys-601 | Lys-107, Lys-116, Lys-123 |

| SC4MOL | Methylsterol monooxygenase 1, SC4MOL | 1.14.13.72 | Lys-85, Lys-87,2 Lys-167, Lys-2843 | ||

| NSDHL | Sterol-4-α-carboxylate 3-dehydrogenase, decarboxylating, NSDHL | 1.1.1.170 | Lys-31, Lys-96, Lys-191 | ||

| HSD17B7 | 3-Keto-steroid reductase, HSD17B7 | 1.1.1.270 | Lys-321 | Lys-176, Lys-188, Lys-301, Lys-311, Lys-329, Lys-3152 | |

| Sterol isomerase | 3-β-Hydroxysteroid Δ8,Δ7-isomerase, EBP | 5.3.3.5 | Lys-221 | ||

| SC5D | Lathosterol oxidase, SC5D | 1.14.21.6 | Ser-253 | Lys-70, Lys-255, Lys-2632 | |

| DHCR7 | 7-Dehydrocholesterol reductase, DHCR7 | 1.3.1.21 | Ser-14,9 Thr-19 | Lys-13, Lys-231, Lys-454, Lys-88,2 Lys-358 | |

| DHCR24 | Δ24-Sterol reductase, DHCR24 | 1.3.1.72 | Thr-110, Tyr-321 | Lys-76, Lys-254, Lys-301, Lys-376, Lys-313,3 Lys-367, Lys-4922 |

a Superscript numbers indicate the total number of references to date; all others are from one reference only, which can be found on PhosphoSitePlus (53).

Regulation by Post-translational Modifications

As one of the first known substrates of AMP-activated protein kinase, HMGCR is well known to be phosphorylated by this kinase (50) and is also known to be ubiquitinated (51). However, despite large-scale proteomic studies indicating a vast number of post-translational modifications on cholesterol synthesis enzymes, including phosphorylation and ubiquitination (Table 2, comprising human studies), only one of these has been investigated specifically. LBR was found to be phosphorylated by Cdc2 kinase (52), which affected its role in chromatin binding, but no mention was made regarding its role in cholesterol synthesis.

Therefore, many cholesterol synthesis enzymes have post-translational modifications. Strikingly, the number of ubiquitination sites is disproportional to the database, with a phosphorylation:ubiquitination site ratio of 1:0.5 in the database (53) but a ratio of 1:3 in cholesterol synthesis enzymes. Hence, this is an area deserving further investigation to begin to understand what role these modifications play in regulating cholesterol synthesis.

Other Effects on Enzyme Activity

Direct Effects of Sterols

It is likely that sterol intermediates or related compounds can directly inhibit enzymes at various steps in the cholesterol synthesis pathway. For example, the final step in the Bloch pathway (Fig. 1) catalyzed by DHCR24 can be inhibited by phytosterols (54), side chain oxysterols like 24,25-EC (21), and steroid hormones (notably progesterone) (55, 56). These effects were observed without affecting protein levels and so are likely direct effects (21, 56). In support of this, phytosterols inhibit DHCR24 via competitive inhibition due to their structural similarity to the substrate desmosterol (54).

Regulation through Cofactors and Auxiliary Proteins

Cholesterol synthesis may be controlled in part through the availability and regulation of cofactors and auxiliary proteins. For example, SREBP controls the production of NADPH, the reducing power required for many steps in cholesterol synthesis (57). Because cholesterol synthesis is a particularly oxygen-intensive process, deprivation of oxygen (hypoxia) slows demethylation of lanosterol and its metabolite 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, resulting in the accumulation of both sterols in cells (44). This finding may have special relevance to certain pathologies, such as solid tumors, which tend to be hypoxic.

There are various lipid carrier proteins that can also potentially regulate cholesterol synthesis. One example is “supernatant protein factor,” named by Konrad Bloch (58), which facilitates cholesterol synthesis by translocating substrate from one enzyme site to another or from an inactive to an active pool (59). Notably, the supernatant protein factor is regulated post-translationally, requiring phosphorylation to stimulate cholesterol synthesis (60). There are doubtless more examples where limiting the availability of cofactors or regulating auxiliary proteins impacts on cholesterol synthesis.

Localization and Redistribution of Cholesterogenic Enzymes

Almost all of the enzymes required for cholesterol synthesis reside in the ER. Considering the remarkable overall efficiency of cholesterol synthesis, it is possible that the enzymes and auxiliary proteins exist as an organized system in the ER membranes, a kind of “cholestesome.” In yeast, certain Erg proteins are known to interact (61), but whether such a cholestesome exists in the mammalian ER remains to be determined. Erg27p and Erg7p interact in yeast, but this is not the case for the mammalian orthologs, HSD17B7 and LS, respectively (61).

Nevertheless, there is a growing list of enzymes that can translocate to other cell compartments under various conditions. Cellular stress induced nuclear localization of DHCR24, which was reversed when the stimulus was removed (62). Several cholesterogenic enzymes can translocate to lipid droplets, usually in response to fatty acid (oleate) treatment. These enzymes include HMGCR (63), NSDHL (64), and SM (65). Interestingly, accumulation of the substrate of SM, squalene, is associated with the clustering of lipid droplets (66).

The localization of NSDHL on lipid droplets has functional significance. Mutations in NSDHL cause the human embryonic developmental disorder CHILD (congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform nevus and limb defects) syndrome. Importantly, a missense mutation of NSDHL causing CHILD syndrome resulted in a protein that was no longer localized on lipid droplets and could not restore the defective growth of a cholesterol auxotrophic cell line (64). Furthermore, in a breast cancer cell model of metastasis, NSDHL translocated to the plasma membrane as its expression increased (67). It was speculated that this translocation to the plasma membrane may be a shortcut for the formation of lipid rafts, thereby promoting signal transduction and cell metastasis. However, it is difficult to see how this would work without the remaining cholesterol synthesis machinery also moving to the plasma membrane.

In some cases, the translocation to another organelle may in fact attenuate cholesterol synthesis. Thus, oleate addition created well developed, NSDHL-positive lipid droplets while simultaneously reducing cellular conversion of lanosterol into cholesterol (64). Additionally, the yeast equivalent of SM, Erg1p, was inactive in lipid droplets (68). Furthermore, in a toxin-induced dopaminergic neuron model of Parkinson disease, LS redistributed from the ER to mitochondria, and the product lanosterol was reduced (69), again suggesting that enzyme translocation reduces flux through the cholesterol synthesis pathway.

Therefore, the redistribution of cholesterol synthesis enzymes from the ER to other organelles may provide another mechanism for regulating the levels and sites of accumulation of intracellular cholesterol and intermediates. Moreover, enzyme movements could be coupled to substrate trafficking as well, considering that certain sterol intermediates (notably zymosterol) also move around the cell (70, 71).

Conclusions, Questions, and Implications

Cholesterol synthesis occurs in a membranous world, where the enzymes, substrates, and products involved tend to be extremely hydrophobic. This can make the study of its regulation challenging, but ultimately rewarding.

There remain many outstanding questions, some of which have been briefly introduced in this minireview. How are post-HMGCR enzymes controlled to modulate levels of regulatory sterols? How important are the various modes of regulation in this (e.g. alternative splicing and post-translational modifications)? Why do certain cholesterogenic enzymes redistribute? How does control vary in different tissues and at the level of the whole organism? The answer to this last question will be facilitated by the increasing sophistication of sterol analysis (e.g. Ref. 72) and modeling the flux through the pathway in a computational framework (e.g. Refs. 73–75).

Understanding how cholesterol synthesis is regulated in cells underpins cholesterol homeostasis of the whole organism and forms the basis of successful therapies for treating human disease. We have come a long way from the experience with triparanol in the early 1960s. Inhibiting DHCR24 and causing desmosterol to accumulate, triparanol was the first drug to directly target the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, but it was withdrawn due to adverse reactions (reviewed in Ref. 76). The cautionary tale of triparanol steered researchers' efforts away from the distal end of the cholesterol synthesis pathway to statins and HMGCR, where the precursor was water-soluble and so should not accumulate. Research into inhibitors of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway has declined, possibly because from both a marketing and therapeutic perspective, there is not a sufficient point of difference with the statins. There may also be lingering safety concerns of targeting the distal end of the pathway, with the specter of triparanol still lurking in the shadows (77). However, it may be that regulatory elements in the control of cholesterol synthesis might offer better strategies than targeting the individual protein directly, as is the case for an increasing number of new targets under investigation (e.g. targeting PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) to stabilize the LDL receptor (78)).

This minireview provides examples of the many and diverse ways that cholesterol synthesis is regulated beyond HMGCR. However, much more remains to be discovered to ascertain how flux through the entirety of this fascinating and vital pathway is controlled.

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Grant APP1008081 and National Heart Foundation of Australia Grant G11S5757 (to A. J. B.).

- HMGCR

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase

- MAS

- meiosis-activating sterol

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- LXR

- liver X receptor

- 24,25-EC

- 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol

- SM

- squalene monooxygenase

- LS

- lanosterol synthase

- SREBP

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- LBR

- lamin B receptor

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- SRE

- sterol regulatory element

- NF-Y

- nuclear factor Y

- miRNA

- microRNA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schoenheimer R., Breusch F. (1933) Synthesis and destruction of cholesterol in the organism. J. Biol. Chem. 103, 439–448 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bloch K. (1965) The biological synthesis of cholesterol. Science 150, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jo Y., Debose-Boyd R. A. (2010) Control of cholesterol synthesis through regulated ER-associated degradation of HMG CoA reductase. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 45, 185–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burg J. S., Espenshade P. J. (2011) Regulation of HMG-CoA reductase in mammals and yeast. Prog. Lipid Res. 50, 403–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas S., Fell D. A. (1998) The role of multiple enzyme activation in metabolic flux control. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 38, 65–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nagashima S., Yagyu H., Ohashi K., Tazoe F., Takahashi M., Ohshiro T., Bayasgalan T., Okada K., Sekiya M., Osuga J., Ishibashi S. (2012) Liver-specific deletion of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase causes hepatic steatosis and death. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 1824–1831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Porter F. D., Herman G. E. (2011) Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 52, 6–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang T. J., Zhang F., Richards J. B., Kestenbaum B., van Meurs J. B., Berry D., Kiel D. P., Streeten E. A., Ohlsson C., Koller D. L., Peltonen L., Cooper J. D., O'Reilly P. F., Houston D. K., Glazer N. L., Vandenput L., Peacock M., Shi J., Rivadeneira F., McCarthy M. I., Anneli P., de Boer I. H., Mangino M., Kato B., Smyth D. J., Booth S. L., Jacques P. F., Burke G. L., Goodarzi M., Cheung C. L., Wolf M., Rice K., Goltzman D., Hidiroglou N., Ladouceur M., Wareham N. J., Hocking L. J., Hart D., Arden N. K., Cooper C., Malik S., Fraser W. D., Hartikainen A. L., Zhai G., Macdonald H. M., Forouhi N. G., Loos R. J., Reid D. M., Hakim A., Dennison E., Liu Y., Power C., Stevens H. E., Jaana L., Vasan R. S., Soranzo N., Bojunga J., Psaty B. M., Lorentzon M., Foroud T., Harris T. B., Hofman A., Jansson J. O., Cauley J. A., Uitterlinden A. G., Gibson Q., Jarvelin M. R., Karasik D., Siscovick D. S., Econs M. J., Kritchevsky S. B., Florez J. C., Todd J. A., Dupuis J., Hypponen E., Spector T. D. (2010) Common genetic determinants of vitamin D insufficiency: a genome-wide association study. Lancet 376, 180–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. He M., Kratz L. E., Michel J. J., Vallejo A. N., Ferris L., Kelley R. I., Hoover J. J., Jukic D., Gibson K. M., Wolfe L. A., Ramachandran D., Zwick M. E., Vockley J. (2011) Mutations in the human SC4MOL gene encoding a methyl sterol oxidase cause psoriasiform dermatitis, microcephaly, and developmental delay. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 976–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sukhanova A., Gorin A., Serebriiskii I. G., Gabitova L., Zheng H., Restifo D., Egleston B. L., Cunningham D., Bagnyukova T., Liu H., Nikonova A., Adams G. P., Zhou Y., Yang D. H., Mehra R., Burtness B., Cai K. Q., Klein-Szanto A., Kratz L. E., Kelley R. I., Weiner L. M., Herman G. E., Golemis E. A., Astsaturov I. (2013) Targeting C4-demethylating genes in the cholesterol pathway sensitizes cancer cells to EGF receptor inhibitors via increased EGF receptor degradation. Cancer Discov. 3, 96–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Song B. L., Javitt N. B., DeBose-Boyd R. A. (2005) Insig-mediated degradation of HMG-CoA reductase stimulated by lanosterol, an intermediate in the synthesis of cholesterol. Cell Metab. 1, 179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lange Y., Ory D. S., Ye J., Lanier M. H., Hsu F. F., Steck T. L. (2008) Effectors of rapid homeostatic responses of endoplasmic reticulum cholesterol and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1445–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leichner G. S., Avner R., Harats D., Roitelman J. (2011) Metabolically regulated endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase. Evidence for requirement of a geranylgeranylated protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 32150–32161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhu J., Mounzih K., Chehab E. F., Mitro N., Saez E., Chehab F. F. (2010) Effects of FoxO4 overexpression on cholesterol biosynthesis, triacylglycerol accumulation, and glucose uptake. J. Lipid Res. 51, 1312–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang C., McDonald J. G., Patel A., Zhang Y., Umetani M., Xu F., Westover E. J., Covey D. F., Mangelsdorf D. J., Cohen J. C., Hobbs H. H. (2006) Sterol intermediates from cholesterol biosynthetic pathway as liver X receptor ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 27816–27826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spann N. J., Garmire L. X., McDonald J. G., Myers D. S., Milne S. B., Shibata N., Reichart D., Fox J. N., Shaked I., Heudobler D., Raetz C. R., Wang E. W., Kelly S. L., Sullards M. C., Murphy R. C., Merrill A. H., Jr., Brown H. A., Dennis E. A., Li A. C., Ley K., Tsimikas S., Fahy E., Subramaniam S., Quehenberger O., Russell D. W., Glass C. K. (2012) Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell 151, 138–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lehmann J. M., Kliewer S. A., Moore L. B., Smith-Oliver T. A., Oliver B. B., Su J.-L., Sundseth S. S., Winegar D. A., Blanchard D. E., Spencer T. A., Willson T. M. (1997) Activation of the nuclear receptor LXR by oxysterols defines a new hormone response pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 3137–3140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spencer T. A., Gayen A. K., Phirwa S., Nelson J. A., Taylor F. R., Kandutsch A. A., Erickson S. K. (1985) 24(S),25-Epoxycholesterol. Evidence consistent with a role in the regulation of hepatic cholesterogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 13391–13394 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dang H., Liu Y., Pang W., Li C., Wang N., Shyy J. Y.-J., Zhu Y. (2009) Suppression of 2,3-oxidosqualene cyclase by high fat diet contributes to liver X receptor-α-mediated improvement of hepatic lipid profile. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6218–6226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wong J., Quinn C. M., Gelissen I. C., Brown A. J. (2008) Endogenous 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol fine-tunes acute control of cellular cholesterol homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 700–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zerenturk E. J., Kristiana I., Gill S., Brown A. J. (2012) The endogenous regulator 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol inhibits cholesterol synthesis at DHCR24 (Seladin-1). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 1269–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horton J. D., Shah N. A., Warrington J. A., Anderson N. N., Park S. W., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (2003) Combined analysis of oligonucleotide microarray data from transgenic and knockout mice identifies direct SREBP target genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12027–12032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bennati A. M., Castelli M., Della Fazia M. A., Beccari T., Caruso D., Servillo G., Roberti R. (2006) Sterol dependent regulation of human TM7SF2 gene expression: role of the encoded 3β-hydroxysterol Δ14-reductase in human cholesterol biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 677–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bennati A. M., Schiavoni G., Franken S., Piobbico D., Della Fazia M. A., Caruso D., De Fabiani E., Benedetti L., Cusella De Angelis M. G., Gieselmann V., Servillo G., Beccari T., Roberti R. (2008) Disruption of the gene encoding 3β-hydroxysterol Δ14-reductase (Tm7sf2) in mice does not impair cholesterol biosynthesis. FEBS J. 275, 5034–5047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Seo Y. K., Jeon T. I., Chong H. K., Biesinger J., Xie X., Osborne T. F. (2011) Genome-wide localization of SREBP-2 in hepatic chromatin predicts a role in autophagy. Cell Metab. 13, 367–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zerenturk E. J., Sharpe L. J., Brown A. J. (2012) Sterols regulate 3β-hydroxysterol Δ24-reductase (DHCR24) via dual sterol regulatory elements: cooperative induction of key enzymes in lipid synthesis by sterol regulatory element binding proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 1350–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nagai M., Sakakibara J., Nakamura Y., Gejyo F., Ono T. (2002) SREBP-2 and NF-Y are involved in the transcriptional regulation of squalene epoxidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 295, 74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murphy C., Ledmyr H., Ehrenborg E., Gåfvels M. (2006) Promoter analysis of the murine squalene epoxidase gene. Identification of a 205 bp homing region regulated by both SREBP'S and NF-Y. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 1213–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guan G., Dai P. H., Osborne T. F., Kim J. B., Shechter I. (1997) Multiple sequence elements are involved in the transcriptional regulation of the human squalene synthase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 10295–10302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inoue J., Sato R., Maeda M. (1998) Multiple DNA elements for sterol regulatory element-binding protein and NF-Y are responsible for sterol-regulated transcription of the genes for human 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A synthase and squalene synthase. J. Biochem. 123, 1191–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Magaña M. M., Osborne T. F. (1996) Two tandem binding sites for sterol regulatory element binding proteins are required for sterol regulation of fatty-acid synthase promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 32689–32694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y., Rogers P. M., Su C., Varga G., Stayrook K. R., Burris T. P. (2008) Regulation of cholesterologenesis by the oxysterol receptor, LXRα. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26332–26339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Y., Rogers P. M., Stayrook K. R., Su C., Varga G., Shen Q., Nagpal S., Burris T. P. (2008) The selective Alzheimer's disease indicator-1 gene (Seladin-1/DHCR24) is a liver X receptor target gene. Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 1716–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Repa J. J., Li H., Frank-Cannon T. C., Valasek M. A., Turley S. D., Tansey M. G., Dietschy J. M. (2007) Liver X receptor activation enhances cholesterol loss from the brain, decreases neuroinflammation, and increases survival of the NPC1 mouse. J. Neurosci. 27, 14470–14480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krycer J. R., Brown A. J. (2011) Cross-talk between the androgen receptor and the liver X receptor. Implications for cholesterol homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20637–20647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Luu W., Sharpe L. J., Stevenson J., Brown A. J. (2012) Akt acutely activates the cholesterogenic transcription factor SREBP-2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fernández-Hernando C., Ramírez C. M., Goedeke L., Suárez Y. (2013) MicroRNAs in metabolic disease. Arterioscl. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 178–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krützfeldt J., Rajewsky N., Braich R., Rajeev K. G., Tuschl T., Manoharan M., Stoffel M. (2005) Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with 'antagomirs.' Nature 438, 685–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Esau C., Davis S., Murray S. F., Yu X. X., Pandey S. K., Pear M., Watts L., Booten S. L., Graham M., McKay R., Subramaniam A., Propp S., Lollo B. A., Freier S., Bennett C. F., Bhanot S., Monia B. P. (2006) miR-122 regulation of lipid metabolism revealed by in vivo antisense targeting. Cell Metab. 3, 87–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Medina M. W., Krauss R. M. (2013) Alternative splicing in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Lipid. 24, 147–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Medina M. W., Gao F., Naidoo D., Rudel L. L., Temel R. E., McDaniel A. L., Marshall S. M., Krauss R. M. (2011) Coordinately regulated alternative splicing of genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis and uptake. PLoS ONE 6, e19420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de la Grange P., Dutertre M., Correa M., Auboeuf D. (2007) A new advance in alternative splicing databases: from catalogue to detailed analysis of regulation of expression and function of human alternative splicing variants. BMC Bioinformatics 8, 180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roitelman J., Simoni R. D. (1992) Distinct sterol and nonsterol signals for the regulated degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 25264–25273 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nguyen A. D., McDonald J. G., Bruick R. K., DeBose-Boyd R. A. (2007) Hypoxia stimulates degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase through accumulation of lanosterol and hypoxia-inducible factor-mediated induction of insigs. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27436–27446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gonzalez R., Carlson J. P., Dempsey M. E. (1979) Two major regulatory steps in cholesterol synthesis by human renal cancer cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 196, 574–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hidaka Y., Satoh T., Kamei T. (1990) Regulation of squalene epoxidase in HepG2 cells. J. Lipid Res. 31, 2087–2094 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gill S., Stevenson J., Kristiana I., Brown A. J. (2011) Cholesterol-dependent degradation of squalene monooxygenase, a control point in cholesterol synthesis beyond HMG-CoA reductase. Cell Metab. 13, 260–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hulce J. J., Cognetta A. B., Niphakis M. J., Tully S. E., Cravatt B. F. (2013) Proteome-wide mapping of cholesterol-interacting proteins in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods 10, 259–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kristiana I., Luu W., Stevenson J., Cartland S., Jessup W., Belani J. D., Rychnovsky S. D., Brown A. J. (2012) Cholesterol through the looking glass. Ability of its enantiomer also to elicit homeostatic responses. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 33897–33904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Clarke P. R., Hardie D. G. (1990) Regulation of HMG-CoA reductase: identification of the site phosphorylated by the AMP-activated protein kinase in vitro and in intact rat liver. EMBO J. 9, 2439–2446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sever N., Song B. L., Yabe D., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S., DeBose-Boyd R. A. (2003) Insig-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of mammalian 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase stimulated by sterols and geranylgeraniol. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 52479–52490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Takano M., Koyama Y., Ito H., Hoshino S., Onogi H., Hagiwara M., Furukawa K., Horigome T. (2004) Regulation of binding of lamin B receptor to chromatin by SR protein kinase and Cdc2 kinase in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13265–13271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hornbeck P. V., Kornhauser J. M., Tkachev S., Zhang B., Skrzypek E., Murray B., Latham V., Sullivan M. (2012) PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D261–D270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fernández C., Suárez Y., Ferruelo A. J., Gómez-Coronado D., Lasunción M. A. (2002) Inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis by Δ22-unsaturated phytosterols via competitive inhibition of sterol Δ24-reductase in mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 366, 109–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Metherall J. E., Waugh K., Li H. (1996) Progesterone inhibits cholesterol biosynthesis in cultured cells. Accumulation of cholesterol precursors. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 2627–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jansen M., Wang W., Greco D., Bellenchi G. C., di Porzio U., Brown A. J., Ikonen E. (2013) What dictates the accumulation of desmosterol in the developing brain? FASEB J. 27, 865–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shimomura I., Shimano H., Korn B. S., Bashmakov Y., Horton J. D. (1998) Nuclear sterol regulatory element-binding proteins activate genes responsible for the entire program of unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in transgenic mouse liver. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 35299–35306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ferguson J. B., Bloch K. (1977) Purification and properties of a soluble protein activator of rat liver squalene epoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 252, 5381–5385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ishibashi T. (2002) Supernatant protein relevant to the activity of membrane-bound enzymes: studies on lathosterol 5-desaturase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292, 1293–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mokashi V., Singh D. K., Porter T. D. (2005) Supernatant protein factor stimulates HMG-CoA reductase in cell culture and in vitro. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 433, 474–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Taramino S., Teske B., Oliaro-Bosso S., Bard M., Balliano G. (2010) Divergent interactions involving the oxidosqualene cyclase and the steroid-3-ketoreductase in the sterol biosynthetic pathway of mammals and yeasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1801, 1232–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wu C., Miloslavskaya I., Demontis S., Maestro R., Galaktionov K. (2004) Regulation of cellular response to oncogenic and oxidative stress by Seladin-1. Nature 432, 640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hartman I. Z., Liu P., Zehmer J. K., Luby-Phelps K., Jo Y., Anderson R. G., DeBose-Boyd R. A. (2010) Sterol-induced dislocation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase from endoplasmic reticulum membranes into the cytosol through a subcellular compartment resembling lipid droplets. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19288–19298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ohashi M., Mizushima N., Kabeya Y., Yoshimori T. (2003) Localization of mammalian NAD(P)H steroid dehydrogenase-like protein on lipid droplets. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36819–36829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wan H. C., Melo R. C., Jin Z., Dvorak A. M., Weller P. F. (2007) Roles and origins of leukocyte lipid bodies: proteomic and ultrastructural studies. FASEB J. 21, 167–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ta M. T., Kapterian T. S., Fei W., Du X., Brown A. J., Dawes I. W., Yang H. (2012) Accumulation of squalene is associated with the clustering of lipid droplets. FEBS J. 279, 4231–4244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Xue T., Zhang Y., Zhang L., Yao L., Hu X., Xu L. X. (2013) Proteomic analysis of two metabolic proteins with potential to translocate to plasma membrane associated with tumor metastasis development and drug targets. J. Proteome Res. 12, 1754–1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Leber R., Landl K., Zinser E., Ahorn H., Spök A., Kohlwein S. D., Turnowsky F., Daum G. (1998) Dual localization of squalene epoxidase, Erg1p, in yeast reflects a relationship between the endoplasmic reticulum and lipid particles. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 375–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lim L., Jackson-Lewis V., Wong L. C., Shui G. H., Goh A. X., Kesavapany S., Jenner A. M., Fivaz M., Przedborski S., Wenk M. R. (2012) Lanosterol induces mitochondrial uncoupling and protects dopaminergic neurons from cell death in a model for Parkinson's disease. Cell Death Differ. 19, 416–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lange Y., Echevarria F., Steck T. L. (1991) Movement of zymosterol, a precursor of cholesterol, among three membranes in human fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 21439–21443 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lusa S., Heino S., Ikonen E. (2003) Differential mobilization of newly synthesized cholesterol and biosynthetic sterol precursors from cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19844–19851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. McDonald J. G., Smith D. D., Stiles A. R., Russell D. W. (2012) A comprehensive method for extraction and quantitative analysis of sterols and secosteroids from human plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 53, 1399–1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Porter J. R., Burg J. S., Espenshade P. J., Iglesias P. A. (2012) Identifying a static nonlinear structure in a biological system using noisy, sparse data. J. Theor. Biol. 300, 232–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Belič A., Pompon D., Monostory K., Kelly D., Kelly S., Rozman D. (2013) An algorithm for rapid computational construction of metabolic networks: a cholesterol biosynthesis example. Comput. Biol. Med. 43, 471–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mazein A., Watterson S., Hsieh W. Y., Griffiths W. J., Ghazal P. (2013) A comprehensive machine-readable view of the mammalian cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Li J. J. (2009) Triumph of the Heart: The Story of Statins, Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gelissen I. C., Brown A. J. (2011) Drug targets beyond HMG-CoA reductase: why venture beyond the statins? Front. Biol. 6, 197–205 [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhang D. W., Lagace T. A., Garuti R., Zhao Z., McDonald M., Horton J. D., Cohen J. C., Hobbs H. H. (2007) Binding of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 to epidermal growth factor-like repeat A of low density lipoprotein receptor decreases receptor recycling and increases degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18602–18612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Vallett S. M., Sanchez H. B., Rosenfeld J. M., Osborne T. F. (1996) A direct role for sterol regulatory element binding protein in activation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 12247–12253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ishimoto K., Tachibana K., Hanano I., Yamasaki D., Nakamura H., Kawai M., Urano Y., Tanaka T., Hamakubo T., Sakai J., Kodama T., Doi T. (2010) Sterol-regulatory-element-binding protein 2 and nuclear factor Y control human farnesyl diphosphate synthase expression and affect cell proliferation in hepatoblastoma cells. Biochem. J. 429, 347–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rozman D., Fink M., Fimia G. M., Sassone-Corsi P., Waterman M. R. (1999) Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP)/cAMP-responsive element modulator (CREM)-dependent regulation of cholesterogenic lanosterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) in spermatids. Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 1951–1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Schiavoni G., Bennati A. M., Castelli M., Fazia M. A., Beccari T., Servillo G., Roberti R. (2010) Activation of TM7SF2 promoter by SREBP-2 depends on a new sterol regulatory element, a GC-box, and an inverted CCAAT-box. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1801, 587–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ohnesorg T., Adamski J. (2005) Promoter analyses of human and mouse 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 94, 259–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Misawa K., Horiba T., Arimura N., Hirano Y., Inoue J., Emoto N., Shimano H., Shimizu M., Sato R. (2003) Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2 interacts with hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 to enhance sterol isomerase gene expression in hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36176–36182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kim J. H., Lee J. N., Paik Y. K. (2001) Cholesterol biosynthesis from lanosterol. A concerted role for Sp1 and NF-Y-binding sites for sterol-mediated regulation of rat 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18153–18160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sakakura Y., Shimano H., Sone H., Takahashi A., Inoue N., Toyoshima H., Suzuki S., Yamada N. (2001) Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins induce an entire pathway of cholesterol synthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 286, 176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]