Background: Hypoxia promotes tumor growth, but connections to translation mechanisms are obscure.

Results: Hypoxia-enhanced tumorsphere growth of breast cancer cells is HIF-1α-dependent, and HIF-1α up-regulates eIF4E1 in hypoxic cancer cells.

Conclusion: HIF-1α promotes cap-dependent translation of selective mRNAs through up-regulating eIF4E1 in cancer cells at hypoxia.

Significance: Our study provides new insights into the translation mechanisms in cancer cells under low O2 concentrations.

Keywords: Cancer Biology, Hypoxia, Hypoxia-inducible Factor (HIF), mRNA, Translation Initiation Factors, Breast Cancer Cells, Cap-dependent Translation, eIF4E

Abstract

Hypoxia promotes tumor evolution and metastasis, and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is a key regulator of hypoxia-related cellular processes in cancer. The eIF4E translation initiation factors, eIF4E1, eIF4E2, and eIF4E3, are essential for translation initiation. However, whether and how HIF-1α affects cap-dependent translation through eIF4Es in hypoxic cancer cells has been unknown. Here, we report that HIF-1α promoted cap-dependent translation of selective mRNAs through up-regulation of eIF4E1 in hypoxic breast cancer cells. Hypoxia-promoted breast cancer tumorsphere growth was HIF-1α-dependent. We found that eIF4E1, not eIF4E2 or eIF4E3, is the dominant eIF4E family member in breast cancer cells under both normoxia and hypoxia conditions. eIF4E3 expression was largely sequestered in breast cancer cells at normoxia and hypoxia. Hypoxia up-regulated the expression of eIF4E1 and eIF4E2, but only eIF4E1 expression was HIF-1α-dependent. In hypoxic cancer cells, HIF-1α-up-regulated eIF4E1 enhanced cap-dependent translation of a subset of mRNAs encoding proteins important for breast cancer cell mammosphere growth. In searching for correlations, we discovered that human eIF4E1 promoter harbors multiple potential hypoxia response elements. Furthermore, using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and luciferase and point mutation assays, we found that HIF-1α utilized hypoxia response elements in the human eIF4E1 proximal promoter region to activate eIF4E1 expression. Our study suggests that HIF-1α promotes cap-dependent translation of selective mRNAs through up-regulating eIF4E1, which contributes to tumorsphere growth of breast cancer cells at hypoxia. The data shown provide new insights into protein synthesis mechanisms in cancer cells at low oxygen levels.

Introduction

Although global translation is suppressed at hypoxia, which contributes to conserve energy and to sustain survival during the period of inefficient ATP production (1–3), a subset of selective mRNAs believed to be involved in the adaptive responses to hypoxia are preferentially translated in cancer cells (4–6). For example, high levels of the c-Myc and Cyclin-D1 oncoproteins, the proangiogenic factors VEGF and Tie2, and the translation initiation factor eukaryotic initiation factor 4E1 (eIF4E1) have been observed in many types of solid tumors (7–10). In addition, eIF4G, ATF4, and ATF6 have been shown to remain associated with high molecular weight polysomes during anoxic stress (0% O2) (11, 12).

Attenuated translation at acute anoxia (0% O2 for 1–4 h) is regulated by phosphorylation of eIF2α, whereas translation repression is maintained by eIF4E inhibition via 4E-BPs2 and 4E-T at prolonged anoxia (0% O2 for 16 h) (2). Hypoxia (0.5–1.5% O2) inhibits protein synthesis through suppression of multiple key regulators of eIF2α, eEF2, p70S6, mTOR, and rpS6 (4, 13–15). Moderate hypoxia (1.5% O2) in combination with serum deprivation effectively inhibits mTOR activity and causes hypophosphorylation of the mTOR substrates 4E-BP1and S6K in normal cells (16). Translational repression in cancer cells under chronic hypoxia and glucose depletion is independent of the eIF2α kinase PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (4, 17).

Several possible mechanisms for bypassing translation inhibition in mammalian cells at hypoxia (1% O2) have been investigated: 1) uncoupling of oxygen-responsive signaling pathways from mTOR functions in breast cancer cells (1), 2) activation of initiation through an HIF-2α·RBM4·eIF4E2 complex in glioblastoma cells (here the HIF-2α·RBM4·eIF4E2 complex captures the 5′-cap and targets mRNAs to polysomes for active translation and therefore evades hypoxia-induced translation repression (18)), 3) internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-dependent initiation in normal and cancerous cells (here the 5′-UTR regions of some oncogenic mRNAs harbor IRES structures, which facilitate direct ribosome binding independent of formation of eIF4F complex at the cap (19, 20)), and 4) IRES-independent initiation of selective mRNAs in normal and cancerous cells (here Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p75Kip2 and VEGF mRNAs are selectively translated by an IRES-independent mechanism in normal and cancer cells (21)). Although these possible bypass pathways for regulating translation in hypoxic cancer cells have been studied, the translation mechanisms underlying the adaptive and malignant phenotype of tumors at hypoxia have remained obscure.

Translation generally begins with the assembly of the eIF4F at the 5′-end of the mRNA at the m7GpppN cap (22, 23). eIF4F consists of the cap-binding protein eIF4E1, the multidomain adaptor protein eIF4G1, and the RNA helicase eIF4A (24). The recruitment of eIF4E1 to eIF4G1 is the key interaction in the eIF4F complex assembly (25, 26). Increased eIF4E1 levels and/or activity have been demonstrated in breast (27, 28), head and neck, colorectal, lung, ovarian (29, 30), prostate (31), bladder (32), brain (33), esophageal (34), and skin and cervical cancers (28, 35) as well as lymphomas (8, 36). The human eIF4E family consists of three members: eIF4E1, eIF4E2 (4EHP; 4E-LP), and eIF4E3 (37, 38). On the other hand, HIF-1α promotes the expression of more than 60 putative genes involved in angiogenesis (such as VEGF, PDGF, FGF-β1, TGF-β3, and Tie2) (39–42); glycolysis (such as enolase-1, hexokinase-2, GLUT1, and GLUT3) (43–46); and cell proliferation, mobility, invasion, and metastasis (such as insulin-like growth factors I and II and c-Met) in solid tumors (47–53). Whether and how HIF-1α affects the cap-dependent translation of a subset of mRNAs via eIF4Es in cancer cells under hypoxia conditions has been unknown.

In this study, we investigated the roles of HIF-1α in translation of selective mRNAs in hypoxic breast cancer cells. We observed that hypoxia promoted cell proliferation and tumorsphere growth of breast cancer cells, but this promotion effect was HIF-1α-dependent. In cancer cells, eIF4E1 was the dominant factor of the eIF4E family under both normoxia and hypoxia conditions. Although hypoxia significantly elevated the expression of eIF4E1 and eIF4E2, the level of cellular eIF4E3 was very low in breast cancer cells at normoxia and hypoxia. On the other hand, HIF-1α significantly up-regulated the expression of eIF4E1 but not that of eIF4E2. We observed that hypoxic cancer cells were more sensitive to the eIF4E-eIF4G interaction inhibitor 4EGI-1 compared with normoxic cancer cells, which suggests a key role of eIF4F-controlled translation initiation in hypoxic cancers. Consistently, we found that HIF-1α utilized hypoxia response elements (HREs) in the proximal promoter region of eIF4E1 to promote eIF4E1 expression. Our study revealed the hypoxia-dependent roles of eIF4E factors in breast cancer cells as mediated by HIF-1α.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells, Antibodies, Plasmids, and Reagents

The HMLER cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Robert Weinberg (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology). FITC-conjugated anti-CD44 (BD Biosciences; G44-26) antibody and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD24 (BD Biosciences, ML15) antibody were used for cell sorting with flow cytometry. Sorted HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells were used in this study. MEGM, mammary epithelial basal medium, and epithelial cell growth medium were purchased from Lonza. The compound (E)-4EGI-1 isomer was ordered from SpeedChemical, and the purity and quality were confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Anti-c-Myc (N terminus) antibody used for immunostaining was ordered from Epitomics (catalog number 1472-1). Anti-Cyclin-D1 antibody used for immunostaining was ordered from Neomarkers (catalog number RM-9104-S). Anti-eIF4E1 (polyclonal; catalog number 9742), anti-eIF4G1 (catalog number 2498), anti-β-actin (catalog number 4967), anti-GAPDH (catalog number 2118S), and anti-α-tubulin (catalog number 2125) antibodies were ordered from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-eIF4E2 (polyclonal; ab63062) and anti-eIF4E3 (polyclonal; ab105947) antibodies were ordered from Abcam. Anti-HIF1-α chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) grade (polyclonal; ab2185), anti-eIF1A, and anti-eIF5 antibodies were ordered from Abcam. Human VEGF-A165 ELISA kit (catalog number KHG0111) was ordered from Invitrogen. NE-PER® Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents were ordered from Thermo Sciences. The c-Myc inhibitor 10058-F4 was ordered from EMD (catalog number 475965). Cyclin-D1 inhibitor PD 0332991 was ordered from Selleck Chemicals. Plasmid HA-HIF1α-pcDNA3 (catalog number 18949) was ordered from Addgene. HIF-1α shRNA (human) lentiviral particles were ordered from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-35561-V). The pGL3-Basic vector (catalog number 1751) was ordered from Promega.

Surface Marker Analysis by Flow Cytometry/Cell Sorting

FITC-conjugated anti-CD44 (BD Biosciences; G44-26) antibody, phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD24 (BD Biosciences; ML15) antibody, and propidium iodide (5 μg/ml) were ordered and used for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) assay in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols.

Hypoxia Treatment

Hypoxia treatment (1% O2) was performed in a hypoxia incubator chamber (Stem Cell Technology Inc.) by supplying it with 1% O2 (balanced by 5% CO2 and 94% N2) for 20–25 min at a rate of over 10 liter/min with a pressure of 1.3–1.5 p.s.i. to get rid of trace of O2 in the chamber. To minimize glucose depletion, we replaced the medium with fresh MEGM (4 ml/well in 6-well plates) every 24 h.

Mammosphere Growth Assays

Single cell mammosphere culture was performed as described (54, 55) with slight modification. For the single cell mammosphere formation assay, the HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) population in single cell suspensions was cultured (1 × 104 cell/well) in ultralow attachment surface 6-well plates (Corning) with the MEGM (Lonza) under normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2) conditions. After 3 or 4 days, mammosphere (size range of 20–300 μm) numbers were counted as described (54, 55). For the compound effects on CD44high/CD24low population mammosphere formation assay, 1 × 104 HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) population cells were cultured in wells of ultralow attachment surface 6-well plates (Corning) at normoxia or hypoxia for 3 days. DMSO, inactive analog 4EGI-N, and (E)-4EGI-1 in a series of concentrations (10, 20, 40, and 60 μm) were added with treatment for 24 h. The CD44high/CD24low population cell mammosphere numbers were counted. Three independent experiments were performed, and statistical data (mean ± S.D.) are shown.

Western Blot Assay

Cellular protein extraction and Western blot assays were performed as described previously with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm PMSF, 1× Roche Complete Mini protease inhibitor mixture, 1× Pierce phosphatase inhibitor mixture) (56). β-Actin and α-tubulin were used as loading controls.

Cytoplasmic Extract/mRNA Preparation

Cytoplasmic VEGF-A165 protein/mRNA preparation was performed with NE-PER® Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents following the manufacturer's instructions. About 2 × 106 HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells treated with DMSO (20 μm), inactive analog 4EGI-N (20 μm), or (E)-4EGI-1 in the indicated concentrations at hypoxia (1% O2) overnight were harvested by trypsin and washed with cold 1× PBS twice followed by centrifugation at 500 × g for 2 min. After removing the supernatant, 200 μl of ice-cold Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent I (with protease inhibitor and phosphoprotease inhibitor) was added followed by vigorous vortexing for 15 s and incubation on ice for 10 min. 11 μl of ice-cold Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent II was added followed by vigorous vortexing for 5 s and incubation for 2 min. After vigorous vortexing for 5 s and centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 5 min, the supernatant (cytoplasmic extract) was immediately transferred into a prechilled tube. Either the cytoplasmic extract was used for cytoplasmic VEGF-A165 ELISA test with VEGF-A165 ELISA kit, or mRNA purification performed using a TRIzol (Invitrogen)-chloroform-isopropyl alcohol-ethanol method followed by real time PCR with VEGF-A165-specific primers.

Quantitative Real Time PCR

Cellular mRNAs were extracted with TRIzol reagent (Qiagen) and cDNAs were prepared. The following gene-specific primers were ordered (Integrated DNA Technologies): 5′-AGGAGGTTG CTAACCCAGAAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CATCTTCCCACATAGGCTCAA-3′ (antisense) for human eIF4E1, 5′-CAGCACACAGAAAGATGGTGA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTCCAGAACTGCTCCACAGAG-3′ (antisense) for eIF4E2, and 5′-ACCACTTTGGGAAGAG GAGAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGTCCCGAACACTGACAC TAA-3′ (antisense) for eIF4E3. Gene-specific primers for quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) of c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, eIF4G1, and VEGF-A165 mRNAs were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies. qPCRs were performed with an ABI 7900HT qPCR machine (Institute of Chemistry and Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School) with RT2 Real-TimeTM SYBR Green/ROX PCR Master Mix (SuperArray). Three independent experiments were performed, and statistical data (mean ± S.D.) are shown.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed as previously described with some modification (56). HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells at hypoxia (1% O2 for 12 h ∼ 24 h) were cross-linked with formaldehyde, quenched with glycine, resuspended in SDS lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with protease inhibitors), sonicated on ice, and centrifuged at 4 °C. Supernatant (400 μl) were diluted to a final volume of 4 ml in a mixture of 9 parts dilution buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 20 mm Tris-HCl, with protease inhibitors, pH 8.0) and 1 part lysis buffer. Mixtures were incubated with 4 μg of anti-HIF-1α antibody sample with rotating at 4 °C overnight followed with incubation with 100 μl of protein A beads with rotating at 4 °C for 4 h. After gentle centrifugation (2000 rpm), beads were resuspended in 1 ml of wash buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 20 mm Tris-HCl, with protease inhibitors, pH 8.0) and washed with wash buffer 3 times followed by one wash with a final wash buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 500 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with protease inhibitors). The immune complexes were eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS, 100 mm NaHCO3) followed by incubation with proteinase K and RNase A (500 μg/ml each) at 37 °C for 30 min. Reverse cross-links were performed by placing the tubes at 65 °C overnight. Immunoprecipitated DNA was extracted and dissolved in sterile water. Quantitative PCR was performed with RT2 Real-time TM SYBR Green/Rox PCR master mix (SuperArray) with primers: 5′-TTGACCCGGCCTAAAGACTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTAAATCTTGCGTGGCGGTA-3′(antisense) for site 1; 5′-GAAATGGCAACG AATGACCAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTTA GTTGAGGTCCCAGGACAA-3′ (antisense) for site 2; 5′-GCCTGGCAGTAAGTGT GACC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGCTTCTGGGAAGTGGA GTC-3′(antisense) for site 3; 5′-CAGGGCCAAACGGACATA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCCGTTTTCTCCTCTTCTGTAGTC-3′ (antisense) for site 4. Three independent experiments were performed and statistical data (mean ± S.D.) are shown.

HIF-1α Knockdown Assays

Lentiviral particles harboring shRNA (human) HIF-1α (sc-35561-V) were ordered from Santa Cruz Biotechnology for HIF-1α knockdown assays. Procedures and reagents for control lentivirus production and lentivirus infection were adapted from the Broad RNAi Consortium protocols as described previously (57). Control and shRNA (h) HIF-1α lentivirus-infected HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells used for mammosphere growth analyses were cultured for 3 days at normoxia and hypoxia. For the qPCR and Western blot assays, control and shRNA (h) HIF-1α lentivirus-infected HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells were cultured for 24 h at normoxia and hypoxia. Total RNAs were extracted using TRIzol reagent (Qiagen), and cellular proteins were extracted with the above mentioned radioimmune precipitation assay buffer.

Transfection and Luciferase Assay

For the luciferase assay, the −171 to +34 bp DNA fragment of human eIF4E1, which harbors the region 4, was cloned into SacI and NheI sites of pGL3-Basic vector with primers 5′-GGTGGGGGAGAGACTGAGCTCCCCAGAAGCCTCTCGTTACTCACGCAGCC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCCAAAGGCGCTAGCCACCGGTTCGACAGTCGCCATCTTAGATCGATCTGATCGCACAACCGCTCC-3′ (antisense). The −65 to +34 bp DNA fragment of human eIF4E was cloned into SacI and NheI sites of pGL3-Basic vector as a control construct with primers 5′-GGACATATCCGTCACGTGGCGAGCTCCTGGCCAATCCGGTTTGAATCTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCCAAAGGCGCTAGCCACCGGTTCGACAGTCGCCATCTTAGATCGATCTGATCGCACAACCGCTCC-3′ (antisense). Point mutation (ACGTG to AAAAG) was performed with QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kits (Agilent). The indicated constructs or construct combination (with HA-HIF1α-pcDNA3 plasmid) was transfected into breast cancer cells HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) and MDA-MB-231 with LipofectamineTM LTX and PLUSTM reagent (Invitrogen) using a standard protocol. After 2 days of recovery after transfection, cells were cultured at normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2 for 24 h). Luciferase activity was measured using the luciferase assay system (Promega) with a Top Count microplate scintillation counter (Canberra). Three independent experiments were performed, and statistical data (mean ± S.D.) are shown.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical experimental data are presented as mean ± S.D. Statistical significance was determined by t test (tail = 1, type = 1). Significance was expressed as follows: *, p < 0.1; **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.01.

RESULTS

Hypoxia Promotes Mammosphere Growth of Breast Cancer Cells

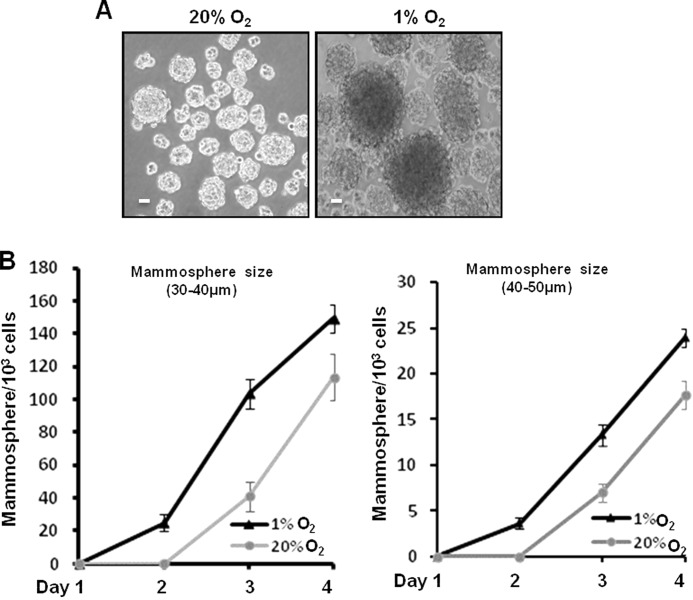

The capacity of mammosphere (tumorsphere) formation and growth of single cancer cells is an important characteristic of tumorigenicity (55, 58, 59). To minimize the potential suppression effects caused by glucose deprivation on tumorsphere growth at hypoxia, we cultured HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) breast cancer cells with double MEGM (4 ml/well in 6-well plate) at hypoxia and replaced the medium with fresh MEGM every 24 h. We cultured 1 × 104 cells/well at normoxia and hypoxia for 4 days and counted the numbers of smaller (30–40-μm) and larger (40–50-μm) mammospheres/1000 cells every day (Fig. 1). At day 4, the small mammosphere count per 1000 cells was 113.6 ± 7.3 at normoxia and 149.3 ± 5.6 at hypoxia (1% O2), and for large mammospheres, the numbers were 17.6 ± 1.53 at normoxia and 24 ± 1 at hypoxia (1% O2). Thus, hypoxia (1% O2) significantly promoted tumorsphere growth of breast cancer cells both in number and size compared with normoxia (20% O2; Fig. 1, A and B). The total cell numbers at day 4 increased at hypoxia in comparison with those at normoxia (data not shown). Our data suggest that hypoxia (1% O2) promotes cell proliferation and tumorsphere growth of these breast cancer cells.

FIGURE 1.

Hypoxia promotes mammosphere growth of breast cancer cells in both size and number. A, single breast cancer cells of HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells (1 × 104/well) were cultured in ultralow attachment surface 6-well plates with MEGM (4 ml/well) at normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2) for 4 days. Representative images of mammospheres at normoxia and hypoxia were taken at the 4th day. Scale bar, 20 μm. B, statistical analyses of mammospheres per 1 × 103 HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells with and without hypoxia treatment over 4 days. At the 4th day, the numbers of 30–40-μm mammospheres were 113.6 ± 7.3 at normoxia and 149.3 ± 5.6 at hypoxia (1% O2), and the numbers of 40–50-μm mammospheres were 17.6 ± 1.53 at normoxia and 24 ± 1 at hypoxia (1% O2). Three independent experiments were performed (mean ± S.D., n = 3). Error bars represent S.D.

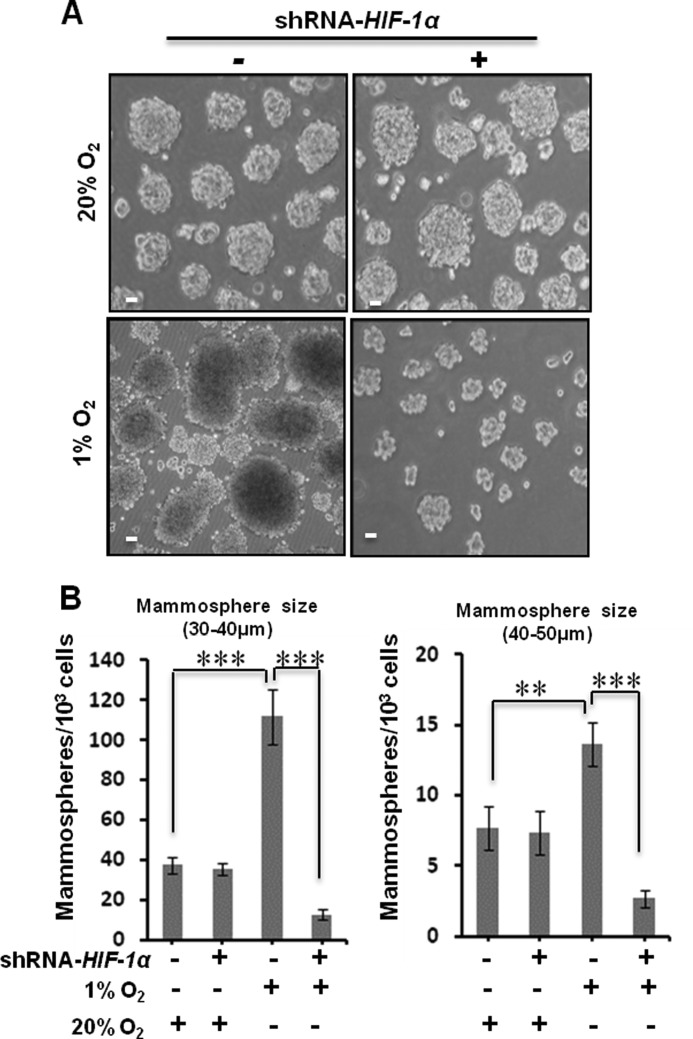

Hypoxia-promoted Breast Cancer Cell Mammosphere Growth Is HIF-1α-dependent

To examine whether HIF-1α plays a role in hypoxia-promoted tumorsphere growth, we cultured HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells with and without transient knockdown of HIF-1α at normoxia and hypoxia conditions for 3 days. At day 3, we measured the mammosphere numbers and found that knockdown of HIF-1α largely reduced the mammosphere numbers at hypoxia but had no effect at normoxia for both classes of mammospheres (Fig. 2, A and B). These observations suggest that hypoxia-promoted cell proliferation and mammosphere growth of breast cancer cell are HIF-1α-dependent.

FIGURE 2.

HIF-1α is necessary for hypoxia-promoted mammosphere growth of breast cancer cells. A, single breast cancer cells of HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells with and without HIF-1α knockdown (by control shRNA and shRNA-HIF-1α) were cultured in ultralow attachment surface 6-well plates (1 × 104/well) with MEGM (4 ml/well) at normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2) for 3 days. Representative images of mammospheres at normoxia and hypoxia were taken at the 3rd day. Scale bar, 20 μm. B, statistical analyses of mammospheres per 1 × 103 HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells with and without HIF-1α knockdown at normoxia (20% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2). At the 3rd day, the numbers of 30–40-μm mammospheres at hypoxia were 112 ± 13.7 in wild type and 12.67 ± 2.5 with HIF-1α knockdown; the numbers of 40–50-μm mammospheres at hypoxia were 13.6 ± 1.5 in wild type and 2.67 ± 0.57 with HIF-1α knockdown. Three independent experiments were performed (mean ± S.D., n = 3). **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.01. Error bars represent S.D.

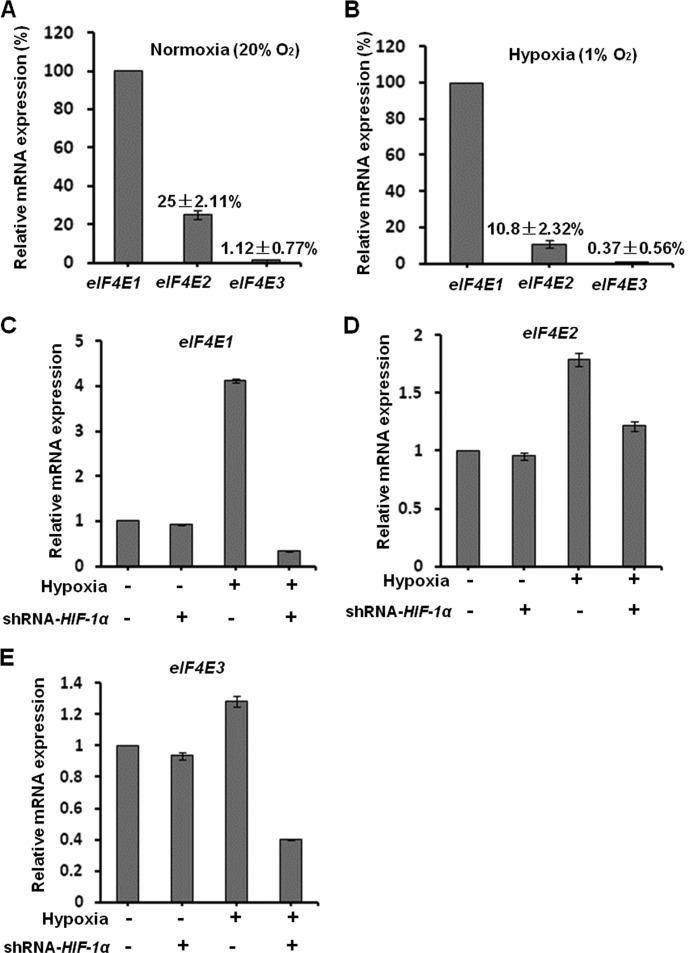

eIF4E1 Is the Dominantly Expressed Member of the Three eIF4E Proteins in Breast Cancer Cells under Normoxia and Hypoxia Conditions

To investigate the expression of the three members of the eIF4E family in breast cancer cells at both normoxia (20% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2 for 24 h), we measured the cellular mRNAs of eIF4E1, eIF4E2, and eIF4E3 by qPCR. Under normoxia conditions, we found that eIF4E2 and eIF4E3 mRNAs are expressed only at 25 ± 2.11 and 1.12 ± 0.77% of eIF4E1 mRNAs, respectively. At hypoxia, cellular eIF4E2 and eIF4E3 mRNAs levels are only 10.8 ± 2.32 and 0.37 ± 0.56% of eIF4E1 mRNAs, respectively (Fig. 3, A and B). These data indicate that eIF4E1 is the dominantly expressed member of the eIF4E family in breast cancer cells at both normoxia and hypoxia. In comparison, the expression of eIF4E3 was very low (only 1% of eIF4E1 at normoxia and 0.3% at hypoxia).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of hypoxia and HIF-1α on transcription of eIF4E1, eIF4E2, and eIF4E3. A, eIF4E1 is dominantly transcribed in breast cancer cells under normoxia (20% O2) conditions. The cellular eIF4E2 and eIF4E3 mRNAs are 25 ± 2.11 and 1.12 ± 0.77% of that of eIF4E1 mRNAs in breast cancer HMLER(CD44high/CD24low) cells at normoxia. Total RNAs were extracted for quantitative real time PCR. Three independent experiments were performed (mean ± S.D., n = 3). B, eIF4E1 is primarily transcribed in breast cancer cells under hypoxia conditions (1% O2 for 24 h). The cellular eIF4E2 and eIF4E3 mRNAs are 10.8 ± 2.32 and 0.37 ± 0.56% of that of eIF4E1 mRNAs at hypoxia. C–E, breast cancer HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells with and without HIF-1α transient knockdown were cultured under normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2) conditions for 24 h. Hypoxia (1% O2) elevates the cellular eIF4E1 level to 4.1-fold of that at normoxia, whereas HIF-1α knockdown abrogates it to 0.33-fold of that at normoxia (C). Hypoxia (1% O2) elevates the cellular eIF4E2 lever to 1.8-fold of that at normoxia (D). Hypoxia (1% O2) does not significantly affect eIF4E3 expression, whereas HIF-1α knockdown decreases it to 0.4-fold of that at normoxia (E). Error bars represent S.D.

Hypoxia-up-regulated Expressions of eIF4E1 and eIF4E3 Are HIF-1α-dependent

To examine the roles of hypoxia and HIF-1α on eIF4E1, eIF4E2, and eIF4E3 transcription in hypoxic cancer cells, we cultured HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells with and without HIF-1α transient knockdown at normoxia and hypoxia conditions for 24 h and measured cellular mRNAs by qPCR. We detected that hypoxia strikingly elevated the expression of eIF4E1 (increased to about 4-fold) and eIF4E2 (increased to about 1.8-fold) in comparison with that at normoxia (Fig. 3, C–E), indicating that hypoxia strongly up-regulates eIF4E1, moderately increases eIF4E2, and has only a small effect on eIF4E3 expression. These data are consistent with the aforementioned observations that the relative expression levels of eIF4E2 compared with eIF4E1 were decreased at hypoxia, which is caused by the fact that the increase of eIF4E1 (4-fold) is greater than that of eIF4E2 (about 1.8-fold). Interestingly, we detected that shRNA-HIF-1α abrogated hypoxia-promoted expression of eIF4E1 (Fig. 3, C–E) but did not significantly affect eIF4E2 expression at normoxia, indicating that hypoxia-up-regulated expression of eIF4E1 is HIF-1α-dependent.

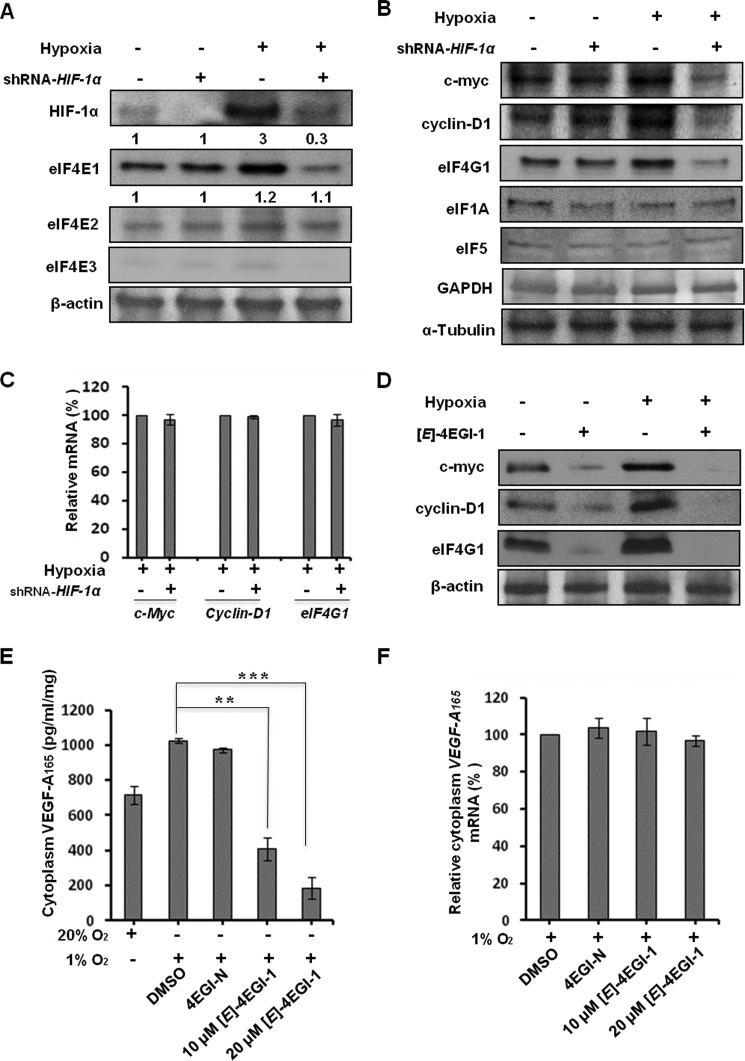

HIF-1α-promoted eIF4E1 Expression Is Important for Cap-dependent Translation of a Subset of mRNAs

To further examine the roles of hypoxia and HIF-1α on eIF4E1, eIF4E2, and eIF4E3, we performed Western blot assays. We observed that hypoxia increased cellular eIF4E1 (about 3-fold) and eIF4E2 (about 1.2-fold) compared with that at normoxia. HIF-1α knockdown significantly decreased eIF4E1 (to about 0.3-fold), but not eIF4E2, in comparison with that at normoxia (Fig. 4A), indicating that hypoxia-promoted eIF4E1 expression is HIF-1α-dependent. We observed that the cellular levels of eIF4E1 proteins were much higher than those of eIF4E2 and eIF4E3 proteins at both normoxia and hypoxia conditions. In particular, eIF4E3 was hardly detectable both at normoxia and hypoxia, indicating that its expression is largely sequestered in cancer cells at both normoxia and hypoxia.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of hypoxia and HIF-1α on cellular eIF4E1, eIF4E2, and eIF4E3 and a subset of oncoproteins. A, hypoxia elevates cellular eIF4E1 protein to about 3-fold, whereas HIF-1α knockdown decreases it to about 0.3-fold of that of wild type at normoxia. Hypoxia increases the cellular eIF4E2 level to about 1.2-fold, whereas HIF-1α knockdown does not significantly reduce it. The eIF4E1 protein is the dominant form among the eIF4E family members under both normoxia and hypoxia conditions. Breast cancer HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells with transient knockdown of HIF-1α by shRNA-HIF-1α were cultured with double fresh MEGM (4 ml/cell in a 6-well plate) under normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2) conditions for another 24 h. Cellular proteins were used for Western blot assays with β-actin as a loading control. The relative protein levels of eIF4E1 and eIF4E2 compared with that in wild type cells at normoxia are shown. B, HIF-1α up-regulates expressions of c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1, but not eIF1A, eIF5, or GAPDH, in hypoxic breast cancer cells. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. C, effects of transient knockdown of HIF-1α by shRNA-HIF-1α on the cellular levels of c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1 mRNAs in hypoxic breast cancer cells. D, eIF4E1-eIF4G1 interaction inhibitor (E)-4EGI-1 (40 μm; 12 h) inhibits hypoxia-promoted expressions of c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1 in hypoxic breast cancer cells. E and F, effects of (E)-4EGI-1 (12 h) on cytoplasmic VEGF-A165 protein (E) and mRNA (F) levels in hypoxic breast cancer cells. Vehicle (DMSO) and negative analog 4EGI-N (20 μm; 12 h) were used as controls. **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.01. Error bars represent S.D.

To examine whether HIF-1α plays a role in translation of a subset of mRNAs, we tested cellular c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, eIF4G1, eIF1A, eIF5, and GAPDH with and without HIF-1α at normoxia and hypoxia. We observed that hypoxia elevated the cellular c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1 proteins and that HIF-1α knockdown dramatically decreased the levels of these proteins but did not significantly reduce the levels of eIF1A, eIF5, or GAPDH (Fig. 4B), suggesting that HIF-1α plays a role in the protein expression of selective genes. Next, we observed that HIF-1α transient knockdown in hypoxic breast cancer cells did not significantly decrease the cellular levels of c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, or eIF4G1 mRNAs (Fig. 4C). In addition, we found that there is no potential HRE (to which HIF-1α binds) in the promoter regions (−700 bp) of these three genes. These observations indicate that HIF-1α-up-regulated c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1 levels in hypoxic cancer cells are not likely caused by HIF-1α-promoted transcription of these genes but by the roles of HIF-1α in translation. To investigate whether HIF-1α-up-regulated eIF4E1 mediates the expression of c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1, we tested the efficacy of (E)-4EGI-1, an active 4EGI-1 isomer that binds eIF4E1 and inhibits the eIF4E1-eIF4G1 interaction (60), on these proteins in hypoxic breast cancer cells. We observed that (E)-4EGI-1 significantly inhibited hypoxia-elevated cellular c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1 levels in breast cancer cells (Fig. 4D) but did not significantly affect the cellular levels of c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1 mRNAs (data not shown), indicating that HIF-1α-up-regulated eIF4E1 facilitates translation of c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1 mRNAs.

VEGF, which is up-regulated by HIF-1α in hypoxic cancer cells (61), promotes cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth (62). We examined the effects of (E)-4EGI-1 on the expression of VEGF-A165 in hypoxic breast cancer cells. We observed that (E)-4EGI-1 dramatically decreased hypoxia-promoted cytoplasmic VEGF-A165 levels (Fig. 4E) but did not significantly affect cytoplasmic VEGF-A165 mRNA under the same conditions (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that hypoxia-promoted VEGF-A165 translation in hypoxic breast cancer cells is largely regulated by eIF4E1-mediated cap-dependent translation. Taken together, the above data demonstrate that HIF-1α-promoted eIF4E1 enhances cap-dependent translation of a subset of mRNAs in breast cancer cells under low oxygen conditions.

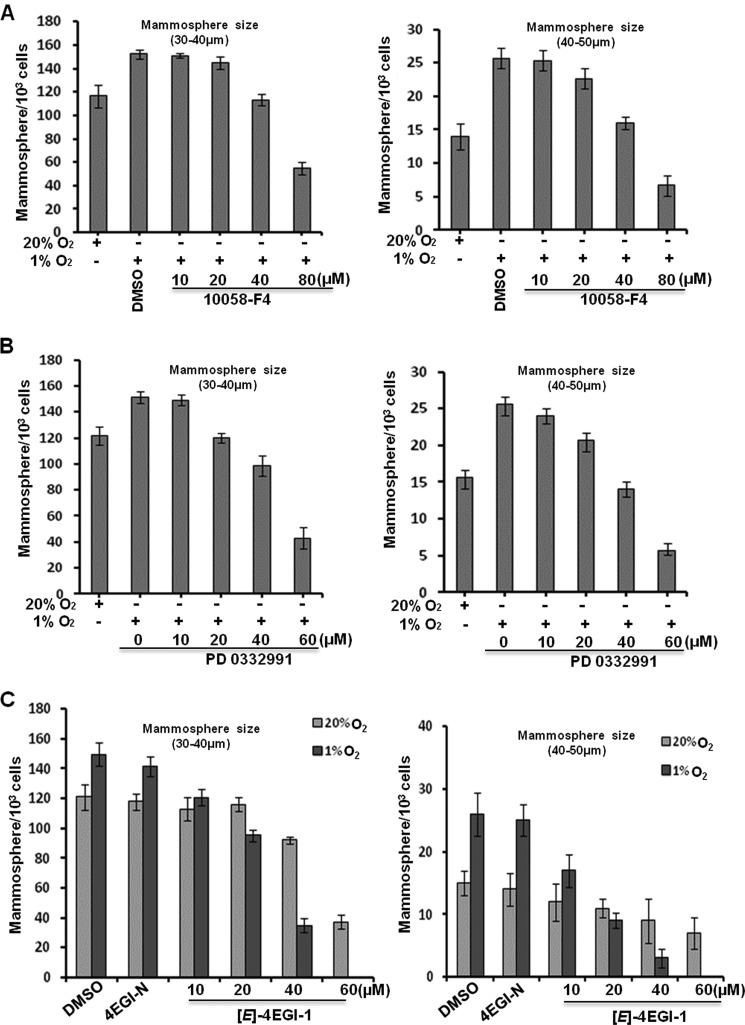

c-Myc and Cyclin-D1 Are Involved in Breast Cancer Cell Mammosphere Growth at Hypoxia

To examine whether c-Myc and Cyclin-D1 are implicated in breast cancer cell mammosphere growth at hypoxia, we tested the efficacy of c-Myc inhibitor 10058-F4 (63) and Cyclin-D1 inhibitor PD 0332991 (64) on HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cell mammospheres. We observed that both inhibitors significantly inhibited hypoxia-promoted mammosphere growth of these breast cancer cells (Fig. 5, A and B), indicating that c-Myc and Cyclin-D1 are important for cancer cell mammosphere growth under hypoxia conditions.

FIGURE 5.

Roles of c-Myc and Cyclin-D1 proteins and eIF4E1-mediated translation in breast cancer cell mammosphere growth. A, c-Myc inhibitor 10058-F4 inhibits hypoxia-promoted mammosphere growth of breast cancer cells. DMSO (40 μm) was used as a control. B, Cyclin-D1 inhibitor PD 0332991 suppresses hypoxia-elevated breast cancer cell mammosphere growth. C, (E)-4EGI-1 preferentially inhibits tumorsphere growth of breast cancer cells under hypoxia in comparison with normoxia. Single HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells were cultures at normoxia (20% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2) for 3 days followed by compound treatment for 1 day. Vehicle (DMSO) and negative analog 4EGI-N (40 μm) were used as controls. Three independent experiments were performed (mean ± S.D., n = 3). Error bars represent S.D.

To further investigate whether eIF4E1-mediated cap-dependent translation dominates in hypoxic cancer cells, we treated tumorspheres with (E)-4EGI-1 together with vehicle and the inactive analogue 4EGI-N at hypoxia and normoxia. As expected, we observed that (E)-4EGI-1 preferentially inhibited hypoxia-promoted tumorsphere growth, whereas vehicle- and 4EGI-N (40 μm)-treated tumorspheres increased in both number and size (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that eIF4E1-regulated cap-dependent translation dominates (at least is indispensible) in mammosphere growth of breast cancer cells under hypoxia conditions. Together, these data demonstrate that HIF-1α-promoted cap-dependent translation of selective mRNAs through up-regulating eIF4E1 contributes to breast cancer cell mammosphere growth at low oxygen levels.

HIF-1α Utilizes HREs in the Proximal Promoter of eIF4E1 to Promote Its Transcription in Hypoxic Cancer Cells

As eIF4E1 is the dominant member of the eIF4E family in breast cancer cells and is the key factor for cap-dependent translation initiation, here we focused on understanding the mechanism of how HIF-1α promotes eIF4E1 expression. We analyzed the promoter regions of human eIF4E1 genes. We found that the −1 kb region of eIF4E1 harbors six potential HREs and that there are two potential HREs in the proximal (<−100 bp) promoter region of eIF4E1 (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

HIF-1α binds and activates HREs in the fourth region of human eIF4E1 promoter. A, the diagram of human eIF4E1. Black box, coding exon; light green box, non-coding exon; arrow, direction from 5′ to 3′. There are six potential HREs in eIF4E1 mRNA −1 kb promoter regions. Regions (1, 2, 3, and 4) in eIF4E1 promoter contain consensus HRE (core sequence, ACGTG).The proximal promoter fourth region (−100 bp) of eIF4E1 harbors two potential HREs. B–E, ChIP assays show binding affinity between HIF-1α and the HREs in four promoter regions of human eIF4E1. F, hypoxia (1% O2 for 12 h) increases the binding affinity between HIF-1α and the fourth HRE in HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells. The bottom images show quantitative PCR products from ChIP assays in agarose gels. IgG was used for mock immunoprecipitation. Three independent experiments were performed (mean ± S.D., n = 3; t test; **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.01). G, luciferase assays in the CD44high/CD24low population show that HREs in the fourth region of eIF4E form an HIF-1α binding site. Hypoxia (1% O2 for 24 h) promotes luciferase activity, whereas point mutation in HREs of the fourth region abrogates these effects. Red letters show the point mutation in HREs in the fourth region. Relative luciferase activities of three experiments are reported (mean ± S.D., n = 3; t test; **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.01). Error bars represent S.D.

We performed ChIP assays with the four promoter regions of eIF4E1 and anti-HIF-1α-specific antibodies. We observed that region 4 exhibited binding affinity to HIF-1α, but regions 1, 2, and 3 did not (Fig. 6, B–E). Furthermore, we found that hypoxia treatment increased binding affinity between region 4 and HIF-1α in breast cancer cells, indicating that HIF-1α might bind the HREs in region 4 (Fig. 6F). To confirm the HREs in region 4 as the HIF-1α binding site, we generated the HRE mutant (ACGTG to AAAAG) and tested it with luciferase assays at normoxia and hypoxia. We observed that hypoxia increased luciferase activity of wild type, and overexpressed HIF-1α further elevated its activity, whereas point mutation abrogated these hypoxia- and HIF-1α-promoted luciferase activities (Fig. 6G). We verified the above results in another type of breast cancer cell, MDA-MB-231 (data not shown). These results demonstrated that HIF-1α utilizes the HREs in region 4 of eIF4E1 to up-regulate eIF4E1 expression in breast cancer cells at low oxygen concentrations. Taken together, our data elucidate the previously unknown mechanisms of HIF-1α promotion of cap-dependent translation of selective mRNAs in hypoxic cancer cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, not only did we provide evidence that HIF-1α promotes cap-dependent translation of selective mRNAs in hypoxic cancer cells, but more significantly, we unraveled the mechanisms by which HIF-1α activates eIF4E1. In particular, we elucidated that hypoxia-promoted tumorsphere growth of breast cancer cells is HIF-1α-dependent. Hypoxia elevates expressions of eIF4E1 and eIF4E2, whereas HIF-1α preferentially promotes eIF4E1 expression in breast cancer cells. The expression of eIF4E3 is largely sequestered in breast cancer cells. We further demonstrated that HIF-1α promotes cap-dependent translation of a subset of mRNAs through up-regulating eIF4E1 (Fig. 7). We identified that HIF-1α utilizes HREs in the proximal promoter region of eIF4E1 to promote its transcription in hypoxic cancer cells. These findings provide new insights into the protein synthesis mechanisms of adaptive advantages in cancer cells in a low oxygen environment.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic diagram for HIF-1α functions in cap-dependent translation of selective mRNAs, cell proliferation, and tumorsphere growth of cancer cells in low O2 environment. Hypoxia promotes the expression of eIF4E family members eIF4E1 and eIF4E2 in breast cancer cells. The expression of eIF4E3 is largely inhibited in cancer cells at both normoxia and hypoxia. HIF-1α binds HREs in the eIF4E1 promoter region and up-regulates eIF4E1 expression. Increased eIF4E1 facilitates formation of eIF4E-eIF4G complex, elevates translation of selective mRNAs important for cancer cell adaptation to hypoxia stresses, and subsequently promotes cancer cell proliferation and tumorsphere growth at low O2 conditions. Breast cancer cells acquire resistance to hypoxia by uncoupling the oxygen-responsive signaling pathway from mTOR function, eliminating suppression of protein synthesis mediated by hypophosphorylated 4E-BPs (1, 66) (in dashed frame). Black arrows or lines are from previous reports of other groups (1, 66); blue arrows or lines are from this study. p-4E-BPs, hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BPs; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; RHEB, Ras homolog enriched in brain.

Importantly, our finding that HIF-1α promoted eIF4E1 expression in hypoxic cancer cells may explain the generally elevated eIF4E1 levels in a wide range of solid tumors, which associate with “chronic” hypoxia (when tumors outgrow their blood supply due to uncontrolled proliferation) and “acute” hypoxia (transient periods of low oxygen caused by aberrant blood flow). This study unravels the previously unknown roles of HIF-1α in translation via eIF4E and might supply a novel pathway of HIF-1α/eIF4E1/eIF4F as targets for the treatment of hypoxic cancers. It is presumed that HIF-1α-up-regulated eIF4E1 increases the availability of eIF4E1 for the translation of a subset of mRNAs with highly structured 5′-UTRs whose translation is highly eIF4E1-dependent.

Interestingly, during the submission of this study, Osborne et al. (65) reported that eIF4E3 competes with eIF4E1 in cap structure binding and therefore acts as a tumor suppressor. We found that the cellular eIF4E3 is very low compared with eIF4E1 in breast cancer cells at both normoxia and hypoxia, indicating that the cancer cells have acquired the capacity to sequester the tumor repression activity of eIF4E3 by unknown mechanisms.

Previous studies reported that HIF-2α·RBM4·eIF4E2 complex-activated initiation is an alternative pathway for cap-dependent translation (18) and that eIF4E2 does not bind to eIF4G (38). We observed that eIF4E1 is most abundant among all eIF4E family members in breast cancer cells under both normoxia and hypoxia conditions, suggesting that eIF4E1, not eIF4E2, may be the primary regulator for cap-dependent translation of a subset of mRNAs, such as c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1, in these breast cancer cells. The observations that hypoxic tumorspheres are more sensitive to the eIF4E1-eIF4G1 interaction inhibitor (E)-4EGI-1 compared with those at normoxia strongly suggest that eIF4E1-mediated cap-dependent translation, but likely not IRES-dependent or eIF4E2-dependent initiation, plays a primary role in translation initiation in hypoxic breast cancer cells. Our data indicate that agents targeting the eIF4E1-eIF4G1 interaction might be potent candidates for the treatment of cancer in a low O2 environment.

The sensitivity of hypoxic tumorspheres to the eIF4E1-eIF4G1 interaction inhibitor (E)-4EGI-1 and the elevated expressions of eIF4E1, c-Myc, Cyclin-D1, and eIF4G1 suggest that hypoxia-suppressed mTOR activity does not affect the cap-dependent translation of selective mRNAs in cancer cells at hypoxia. This is in agreement with previous reports that breast cancer cells acquire resistance to uncoupling hypoxia-responsive signaling of mTOR activity from cap-dependent translation repression. Our observations that VEGF is dominantly regulated by eIF4E1-mediated cap-dependent translation are consistent with previous reports that VEGF is primarily mediated by IRES-independent translation (21). We observed that hypoxia promoted eIF4E2 expression, which was not significantly decreased by HIF-1α knockdown, suggesting that eIF4E2 transcription is not (at least is not largely) regulated by HIF-1α. The upstream pathway mediating eIF4E2 expression needs future elucidation.

The multidomain scaffold adaptor protein eIF4G1 is required for eIF4E1-involved cap-dependent and IRES-dependent translation initiation. We observed that hypoxia significantly elevated cellular eIF4G1, whereas HIF-1α depletion significantly decreased eIF4G1, suggesting that the expression of eIF4G1 in hypoxic cancer cells is at least partly HIF-1α-dependent. Whether HIF-1α-promoted eIF4G1 expression facilitates IRES-dependent initiation in hypoxic cancer cells is a concern for future work. In summary, our study demonstrated that HIF-1α-promoted cap-dependent translation of a subset of mRNAs through up-regulating eIF4E1 is a driving element of tumor growth, providing a novel pathway of protein synthesis mechanisms in cancer cells at low oxygen levels.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Robert Weinberg of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for the generous gift of the HMLER cell line. We thank the Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School for imaging.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 CA068262 (to G. W.).

- 4E-BP

- eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein

- HIF

- hypoxia-inducible factor

- eIF4E

- eukaryotic translation initiation factor-4E

- HRE

- hypoxia response element

- mTor

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- IRES

- internal ribosome entry site

- HMLER

- human mammalian epithelial

- MEGM

- mammary epithelial cell growth medium

- qPCR

- quantitative real time PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1. Connolly E., Braunstein S., Formenti S., Schneider R. J. (2006) Hypoxia inhibits protein synthesis through a 4E-BP1 and elongation factor 2 kinase pathway controlled by mTOR and uncoupled in breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 3955–3965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koritzinsky M., Magagnin M. G., van den Beucken T., Seigneuric R., Savelkouls K., Dostie J., Pyronnet S., Kaufman R. J., Weppler S. A., Voncken J. W., Lambin P., Koumenis C., Sonenberg N., Wouters B. G. (2006) Gene expression during acute and prolonged hypoxia is regulated by distinct mechanisms of translational control. EMBO J. 25, 1114–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keith B., Johnson R. S., Simon M. C. (2012) HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu L., Cash T. P., Jones R. G., Keith B., Thompson C. B., Simon M. C. (2006) Hypoxia-induced energy stress regulates mRNA translation and cell growth. Mol. Cell 21, 521–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhong H., De Marzo A. M., Laughner E., Lim M., Hilton D. A., Zagzag D., Buechler P., Isaacs W. B., Semenza G. L., Simons J. W. (1999) Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in common human cancers and their metastases. Cancer Res. 59, 5830–5835 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elson D. A., Ryan H. E., Snow J. W., Johnson R., Arbeit J. M. (2000) Coordinate up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α and HIF-1 target genes during multi-stage epidermal carcinogenesis and wound healing. Cancer Res. 60, 6189–6195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mamane Y., Petroulakis E., Rong L., Yoshida K., Ler L. W., Sonenberg N. (2004) eIF4E—from translation to transformation. Oncogene 23, 3172–3179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruggero D., Montanaro L., Ma L., Xu W., Londei P., Cordon-Cardo C., Pandolfi P. P. (2004) The translation factor eIF-4E promotes tumor formation and cooperates with c-Myc in lymphomagenesis. Nat. Med. 10, 484–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Folkman J. (1995) Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat. Med. 1, 27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miyagi Y., Sugiyama A., Asai A., Okazaki T., Kuchino Y., Kerr S. J. (1995) Elevated levels of eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF-4E, mRNA in a broad spectrum of transformed cell lines. Cancer Lett. 91, 247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bauer C., Brass N., Diesinger I., Kayser K., Grässer F. A., Meese E. (2002) Overexpression of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G-1) in squamous cell lung carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 98, 181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blais J. D., Filipenko V., Bi M., Harding H. P., Ron D., Koumenis C., Wouters B. G., Bell J. C. (2004) Activating transcription factor 4 is translationally regulated by hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 7469–7482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Romero-Ruiz A., Bautista L., Navarro V., Heras-Garvín A., March-Díaz R., Castellano A., Gómez-Díaz R., Castro M. J., Berra E., López-Barneo J., Pascual A. (2012) Prolyl hydroxylase-dependent modulation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 activity and protein translation under acute hypoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 9651–9658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knaup K. X., Jozefowski K., Schmidt R., Bernhardt W. M., Weidemann A., Juergensen J. S., Warnecke C., Eckardt K. U., Wiesener M. S. (2009) Mutual regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor and mammalian target of rapamycin as a function of oxygen availability. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 88–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhu K., Chan W., Heymach J., Wilkinson M., McConkey D. J. (2009) Control of HIF-1α expression by eIF2α phosphorylation-mediated translational repression. Cancer Res. 69, 1836–1843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van den Beucken T., Koritzinsky M., Wouters B. G. (2006) Translational control of gene expression during hypoxia. Cancer Biol. Ther. 5, 749–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomas J. D., Dias L. M., Johannes G. J. (2008) Translational repression during chronic hypoxia is dependent on glucose levels. RNA 14, 771–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uniacke J., Holterman C. E., Lachance G., Franovic A., Jacob M. D., Fabian M. R., Payette J., Holcik M., Pause A., Lee S. (2012) An oxygen-regulated switch in the protein synthesis machinery. Nature 486, 126–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Silvera D., Formenti S. C., Schneider R. J. (2010) Translational control in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 254–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braunstein S., Karpisheva K., Pola C., Goldberg J., Hochman T., Yee H., Cangiarella J., Arju R., Formenti S. C., Schneider R. J. (2007) A hypoxia-controlled cap-dependent to cap-independent translation switch in breast cancer. Mol. Cell 28, 501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Young R. M., Wang S. J., Gordan J. D., Ji X., Liebhaber S. A., Simon M. C. (2008) Hypoxia-mediated selective mRNA translation by an internal ribosome entry site-independent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 16309–16319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marintchev A., Wagner G. (2004) Translation initiation: structures, mechanisms and evolution. Q. Rev. Biophys. 37, 197–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aitken C. E., Lorsch J. R. (2012) A mechanistic overview of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 568–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pestova T. V., Kolupaeva V. G., Lomakin I. B., Pilipenko E. V., Shatsky I. N., Agol V. I., Hellen C. U. (2001) Molecular mechanisms of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7029–7036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gross J. D., Moerke N. J., von der Haar T., Lugovskoy A. A., Sachs A. B., McCarthy J. E., Wagner G. (2003) Ribosome loading onto the mRNA cap is driven by conformational coupling between eIF4G and eIF4E. Cell 115, 739–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. von der Haar T., Gross J. D., Wagner G., McCarthy J. E. (2004) The mRNA cap-binding protein eIF4E in post-transcriptional gene expression. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coleman L. J., Peter M. B., Teall T. J., Brannan R. A., Hanby A. M., Honarpisheh H., Shaaban A. M., Smith L., Speirs V., Verghese E. T., McElwaine J. N., Hughes T. A. (2009) Combined analysis of eIF4E and 4E-binding protein expression predicts breast cancer survival and estimates eIF4E activity. Br. J. Cancer 100, 1393–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Benedetti A., Graff J. R. (2004) eIF-4E expression and its role in malignancies and metastases. Oncogene 23, 3189–3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Noske A., Lindenberg J. L., Darb-Esfahani S., Weichert W., Buckendahl A. C., Röske A., Sehouli J., Dietel M., Denkert C. (2008) Activation of mTOR in a subgroup of ovarian carcinomas: correlation with p-eIF-4E and prognosis. Oncol. Rep. 20, 1409–1417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Frederickson R. M., Montine K. S., Sonenberg N. (1991) Phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E is increased in Src-transformed cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 2896–2900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Graff J. R., Konicek B. W., Lynch R. L., Dumstorf C. A., Dowless M. S., McNulty A. M., Parsons S. H., Brail L. H., Colligan B. M., Koop J. W., Hurst B. M., Deddens J. A., Neubauer B. L., Stancato L. F., Carter H. W., Douglass L. E., Carter J. H. (2009) eIF4E activation is commonly elevated in advanced human prostate cancers and significantly related to reduced patient survival. Cancer Res. 69, 3866–3873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fan S., Ramalingam S. S., Kauh J., Xu Z., Khuri F. R., Sun S. Y. (2009) Phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 (eIF4E) is elevated in human cancer tissues. Cancer Biol. Ther. 8, 1463–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tejada S., Lobo M. V., García-Villanueva M., Sacristán S., Pérez-Morgado M. I., Salinas M., Martín M. E. (2009) Eukaryotic initiation factors (eIF) 2α and 4E expression, localization, and phosphorylation in brain tumors. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 57, 503–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salehi Z., Mashayekhi F. (2006) Expression of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) and 4E-BP1 in esophageal cancer. Clin. Biochem. 39, 404–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thumma S. C., Kratzke R. A. (2007) Translational control: a target for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 258, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wendel H. G., Silva R. L., Malina A., Mills J. R., Zhu H., Ueda T., Watanabe-Fukunaga R., Fukunaga R., Teruya-Feldstein J., Pelletier J., Lowe S. W. (2007) Dissecting eIF4E action in tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 21, 3232–3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rhoads R. E. (2009) eIF4E: new family members, new binding partners, new roles. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 16711–16715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Joshi B., Cameron A., Jagus R. (2004) Characterization of mammalian eIF4E-family members. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 2189–2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maxwell P. H., Dachs G. U., Gleadle J. M., Nicholls L. G., Harris A. L., Stratford I. J., Hankinson O., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J. (1997) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 modulates gene expression in solid tumors and influences both angiogenesis and tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 8104–8109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bos R., van Diest P. J., de Jong J. S., van der Groep P., van der Valk P., van der Wall E. (2005) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α is associated with angiogenesis, and expression of bFGF, PDGF-BB, and EGFR in invasive breast cancer. Histopathology 46, 31–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bolat F., Haberal N., Tunali N., Aslan E., Bal N., Tuncer I. (2010) Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hypoxia inducible factor 1 α (HIF-1α), and transforming growth factors β1 (TGFβ1) and β3 (TGFβ3) in gestational trophoblastic disease. Pathol. Res. Pract. 206, 19–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ryan H. E., Lo J., Johnson R. S. (1998) HIF-1α is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. EMBO J. 17, 3005–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hoskin P. J., Sibtain A., Daley F. M., Wilson G. D. (2003) GLUT1 and CAIX as intrinsic markers of hypoxia in bladder cancer: relationship with vascularity and proliferation as predictors of outcome of ARCON. Br. J. Cancer 89, 1290–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chung J., Roberts A. M., Chow J., Coady-Osberg N., Ohh M. (2006) Homotypic association between tumour-associated VHL proteins leads to the restoration of HIF pathway. Oncogene 25, 3079–3083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jiang B. H., Agani F., Passaniti A., Semenza G. L. (1997) V-SRC induces expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and transcription of genes encoding vascular endothelial growth factor and enolase 1: involvement of HIF-1 in tumor progression. Cancer Res. 57, 5328–5335 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mathupala S. P., Rempel A., Pedersen P. L. (2001) Glucose catabolism in cancer cells: identification and characterization of a marked activation response of the type II hexokinase gene to hypoxic conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43407–43412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang H., Li H., Xi H. S., Li S. (2012) HIF1α is required for survival maintenance of chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. Blood 119, 2595–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Heddleston J. M., Li Z., Lathia J. D., Bao S., Hjelmeland A. B., Rich J. N. (2010) Hypoxia inducible factors in cancer stem cells. Br. J. Cancer 102, 789–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Keith B., Simon M. C. (2007) Hypoxia-inducible factors, stem cells, and cancer. Cell 129, 465–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tanaka H., Yamamoto M., Hashimoto N., Miyakoshi M., Tamakawa S., Yoshie M., Tokusashi Y., Yokoyama K., Yaginuma Y., Ogawa K. (2006) Hypoxia-independent overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α as an early change in mouse hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 66, 11263–11270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lang S. A., Moser C., Gaumann A., Klein D., Glockzin G., Popp F. C., Dahlke M. H., Piso P., Schlitt H. J., Geissler E. K., Stoeltzing O. (2007) Targeting heat shock protein 90 in pancreatic cancer impairs insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling, disrupts an interleukin-6/signal-transducer and activator of transcription 3/hypoxia-inducible factor-1α autocrine loop, and reduces orthotopic tumor growth. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 6459–6468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Scarpino S., Cancellario d'Alena F., Di Napoli A., Pasquini A., Marzullo A., Ruco L. P. (2004) Increased expression of Met protein is associated with up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) in tumour cells in papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. J. Pathol. 202, 352–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Talks K. L., Turley H., Gatter K. C., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., Harris A. L. (2000) The expression and distribution of the hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α in normal human tissues, cancers, and tumor-associated macrophages. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 411–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dontu G., Abdallah W. M., Foley J. M., Jackson K. W., Clarke M. F., Kawamura M. J., Wicha M. S. (2003) In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 17, 1253–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ince T. A., Richardson A. L., Bell G. W., Saitoh M., Godar S., Karnoub A. E., Iglehart J. D., Weinberg R. A. (2007) Transformation of different human breast epithelial cell types leads to distinct tumor phenotypes. Cancer Cell 12, 160–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yi T., Tan K., Cho S. G., Wang Y., Luo J., Zhang W., Li D., Liu M. (2010) Regulation of embryonic kidney branching morphogenesis and glomerular development by KISS1 receptor (Gpr54) through NFAT2- and Sp1-mediated Bmp7 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17811–17820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Moffat J., Grueneberg D. A., Yang X., Kim S. Y., Kloepfer A. M., Hinkle G., Piqani B., Eisenhaure T. M., Luo B., Grenier J. K., Carpenter A. E., Foo S. Y., Stewart S. A., Stockwell B. R., Hacohen N., Hahn W. C., Lander E. S., Sabatini D. M., Root D. E. (2006) A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell 124, 1283–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Al-Hajj M., Wicha M. S., Benito-Hernandez A., Morrison S. J., Clarke M. F. (2003) Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 3983–3988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gupta P. B., Onder T. T., Jiang G., Tao K., Kuperwasser C., Weinberg R. A., Lander E. S. (2009) Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell 138, 645–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Moerke N. J., Aktas H., Chen H., Cantel S., Reibarkh M. Y., Fahmy A., Gross J. D., Degterev A., Yuan J., Chorev M., Halperin J. A., Wagner G. (2007) Small-molecule inhibition of the interaction between the translation initiation factors eIF4E and eIF4G. Cell 128, 257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shweiki D., Itin A., Soffer D., Keshet E. (1992) Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature 359, 843–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Guo P., Fang Q., Tao H. Q., Schafer C. A., Fenton B. M., Ding I., Hu B., Cheng S. Y. (2003) Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor by MCF-7 breast cancer cells promotes estrogen-independent tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 63, 4684–4691 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yin X., Giap C., Lazo J. S., Prochownik E. V. (2003) Low molecular weight inhibitors of Myc-Max interaction and function. Oncogene 22, 6151–6159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Liu N. A., Jiang H., Ben-Shlomo A., Wawrowsky K., Fan X. M., Lin S., Melmed S. (2011) Targeting zebrafish and murine pituitary corticotroph tumors with a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8414–8419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Osborne M. J., Volpon L., Kornblatt J. A., Culjkovic-Kraljacic B., Baguet A., Borden K. L. (2013) eIF4E3 acts as a tumor suppressor by utilizing an atypical mode of methyl-7-guanosine cap recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 3877–3882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Brugarolas J., Lei K., Hurley R. L., Manning B. D., Reiling J. H., Hafen E., Witters L. A., Ellisen L. W., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2004) Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 18, 2893–2904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]