Background: The mechanism underlying MDSC persistence in tumor-bearing hosts is elusive.

Results: IRF8 is down-regulated in MDSCs, resulting in Fas, Bax, and Bcl-xL deregulation and decreased spontaneous apoptosis.

Conclusion: Increased resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis is at least partially responsible for MDSC accumulation.

Significance: Targeting Bcl-xL is potentially an effective approach to suppress MDSCs in cancer therapy.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Bax, Bcl-2 Family, Fas, Myeloid Cell

Abstract

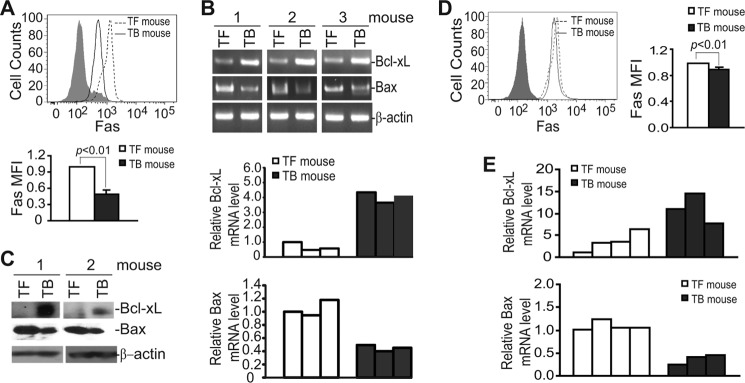

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are heterogeneous immature myeloid cells that accumulate in response to tumor progression. Compelling data from mouse models and human cancer patients showed that tumor-induced inflammatory mediators induce MDSC differentiation. However, the mechanisms underlying MDSC persistence is largely unknown. Here, we demonstrated that tumor-induced MDSCs exhibit significantly decreased spontaneous apoptosis as compared with myeloid cells with the same phenotypes from tumor-free mice. Consistent with the decreased apoptosis, cell surface Fas receptor decreased significantly in tumor-induced MDSCs. Screening for changes of key apoptosis mediators downstream the Fas receptor revealed that expression levels of IRF8 and Bax are diminished, whereas expression of Bcl-xL is increased in tumor-induced MDSCs. We further determined that IRF8 binds directly to Bax and Bcl-x promoter in primary myeloid cells in vivo, and IRF8-deficient MDSC-like cells also exhibit increased Bcl-xL and decreased Bax expression. Analysis of CD69 and CD25 levels revealed that cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are partially activated in tumor-bearing hosts. Strikingly, FasL but not perforin and granzymes were selectively activated in CTLs in the tumor-bearing host. ABT-737 significantly increased the sensitivity of MDSCs to Fas-mediated apoptosis in vitro. More importantly, ABT-737 therapy increased MDSC spontaneous apoptosis and decreased MDSC accumulation in tumor-bearing mice. Our data thus determined that MDSCs use down-regulation of IRF8 to alter Bax and Bcl-xL expression to deregulate the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway to evade elimination by host CTLs. Therefore, targeting Bcl-xL is potentially effective in suppression of MDSC persistence in cancer therapy.

Introduction

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)2 consist of a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells of various differentiation stages and are induced under various pathological conditions, including infection, chronic inflammation, trauma, stress, and cancer (1–5). In human cancer patients and mouse tumor models, massive accumulation of MDSCs in bone marrow, peripheral blood, lymphoid tissue, and tumor tissue is a hallmark of tumor progression (6–10). One key function of MDSCs is immune suppression, and it has been shown that MDSCs use diverse mechanisms to inhibit the effector functions of T cells and NK cells (1, 3, 8, 11–14). Moreover, MDSCs modulate tumor microenvironment favorable for angiogenesis, tumor growth, and progression through non-immunologic way, which complements the pro-tumor activity of tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils (15). Therefore, by virtue of their functions as suppressors of anti-tumor immunity and producers of growth enhancers, MDSCs are widely recognized as potent tumor promoters that are key targets in cancer immunotherapy.

The mechanism underlying MDSC differentiation has been the subject of extensive studies. It is well established that MDSCs arise from myeloid progenitor cells in response to pro-inflammatory mediators in the tumor microenvironment (16, 17). Various proinflammatory factors have been linked to MDSC differentiation in tumor-bearing hosts (18–34). These prominent studies established the concept that tumor-derived proinflammatory factors induce MDSC differentiation in the tumor-bearing host. However, the mechanism underlying MDSC turnover and persistence in tumor-bearing hosts is largely unknown.

Interestingly, it was recently shown that host cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) use FasL to induce apoptosis to eliminate MDSCs in tumor-bearing hosts (35). It is well known that the Fas-FasL system plays a key role in the host immune cell-mediated elimination of autoreactive T cells or activated effector T cells after an immune response to suppress autoimmune disease, such as autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, and in suppression of cancerous cells (36). Cancer cells often acquire resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis through either down-regulation of the death receptor Fas or through altering the expression levels of key mediators of the Fas-mediated apoptosis signaling pathways (37, 38). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that MDSCs use deregulation of the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway to evade elimination to persist in tumor-bearing hosts. To test this hypothesis, we have conducted a systematic analysis of MDSC apoptosis and observed that tumors induce IRF8 silencing in MDSCs, resulting in altered expression of Fas, Bcl-xL, and Bax to evade CTL-exerted and FasL-induced apoptosis to persist in vivo. More importantly, we demonstrated that pharmacologic inhibition of Bcl-xL activity is effective in induction of spontaneous MDSC apoptosis and in suppression of MDSC persistence in tumor-bearing mice in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and Cells

BALB/c mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute Frederick mouse facility. Faslgld mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. IRF8 KO mice were kindly provided by Dr. Keiko Ozato (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). All mice were housed, maintained, and studied in accordance with approved National Institutes of Health and Georgia Regents University guidelines for animal use and handling. 4T1 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). Colon26 cells were kindly provided by William E. Carson, III (Ohio State University) and were as described (28). 32D.Vector and 32D.IRF8 cells were as previously described (39).

Human Blood Specimens

Blood specimens were collected from consented healthy donors from Augusta Shepeard Community Blood Center and from consented breast and colorectal cancer patients at Georgia Regents University Cancer Center. All studies with human specimens were performed according to approved protocols.

Reagents

ABT-737 was provided by Abbott Laboratories. FasL (Mega-Fas Ligand®, kindly provided by Drs. Steven Butcher and Lars Damstrup at Topotarget A/S, Denmark) is a recombinant fusion protein that consists of three human FasL extracellular domains linked to a protein backbone comprising the dimmer-forming collagen domain of human adiponectin. The Mega-Fas Ligand was produced as a glycoprotein in mammalian cells using Good Manufacturing Practice compliant process in Topotarget A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Mouse Models of Tumor-induced MDSCs

4T1 cells (1 × 104 cells in 100 μl of Hanks' balanced salt solution) were injected orthotopically into the mammary fat pad on the mouse abdomen. Colon26 cells (5 × 105 cells in 20 μl of Hanks' balanced salt solution) were surgically implanted into cecal walls of BALB/c mice.

Immune Cell Purification

MDSCs, CD8+ T cells, and other subsets of immune cells were isolated from mouse spleens as previously described (40).

Complete Blood Cell Counts

Whole blood was collected from mice. Complete blood counts with differential were performed in Georgia Laboratory Animal Diagnostic Service (Athens, GA).

RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells or tissues using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and used for RT-PCR analysis of gene expression as described (40). The PCR primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Western Blotting Analysis

Western blotting analysis was performed as previously described (41). Anti-IRF8 (C-19) and anti-Bax (B-20) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), Bcl-xL was obtained from BD Biosciences, anti-β-actin was obtained from Sigma, anti-FLIP antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Biotech, and anti-caspase 8 antibodies (AF705 and AF1650) were obtained from R&D Systems.

Apoptosis Assays

For in vitro apoptosis assay, cells were treated with ABT-737 and FasL for ∼16–24 h and then stained with FITC-CD11b mAb, PE-Gr1 mAbs, Alex Fluor 647-annexin V (all from Biolegend, San Diego, CA), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described (40, 42). For spontaneous MDSC apoptosis assay, a single-cell suspension was prepared from spleens in cold PBS. Cells were washed in cold annexin V binding buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm CaCl2), resuspended in annexin V binding buffer, and stained with FITC-CD11b mAb, PE-Gr1 mAb, Alex Fluor 647-annexin V, and DAPI. The stained cells were analyzed immediately with flow cytometry. To measure % MDSCs, spleen cells were treated with red cell lysis buffer (150 mm NH4Cl, 10 mm KHCO3, and 0.1 mm Na2EDTA, pH 7.2) to remove red blood cells and then stained with FITC-CD11b mAb and PE-Gr1 mAb and analyzed with flow cytometry.

Cell Surface Marker Analysis

Cells were stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibody as previously described (42). Fluorescent dye-conjugated anti-CD4, CD8, CD11b, Gr1, Fas, and FasL mAbs were obtained from Biolegend.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

CD11b+ cells were enriched (about 70% purity) by depleting other subsets of cells with respective mAbs and magnetic beads as previously described (40). Chromatin immunoprecipitation was carried out using anti-IRF8 antibody (C-19; sc-6058x, Santa Cruz) and protein A-agarose/salmon sperm DNA (Millipore, Temecula, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Goat IgG (sc-2028, Santa Cruz) was used as negative control.

Protein-DNA in Vitro Binding Assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared from 32D.Vector and 32D.IRF8 cells, respectively. Double-stranded DNA probes were prepared from synthesized oligonucleotides. The following oligonucleotides are synthesized: 5′-GAAGAAAGGAAGAAAGAGAAAAAAAGTAGGTC-3′ (WT interferon-stimulated response element (ISRE) element 1 probe sense), 5′-GACCTACTTTTTTTCTCTTTCTTCCTTTCTTC-3′ (WT ISRE element 1 probe antisense), 5′-GGACGAACGCAGATAGAGTAATAACGTACGAC-3′ (mutant ISRE element 1 probe sense), 5′-GTCGTACGTTATTACTCTATCTGCGTTCGTCC-3′ (mutant ISRE element 1 probe antisense), 5′-ACAACCAAAAGAAAAAAGAAAGAAAGAAAGAAAGAAA-3′ (WT ISRE element 2 probe sense), 5′-TTTCTTTCTTTCTTTCTTTCTTTTTTCTTTTGGTTGT-3′ (WT ISRE element 2 probe antisense), 5′-ACCACCTAACGACAATAGTAACAATGAACGAATGAAT-3′ (mutant ISRE element 2 probe sense), and 5′-ATTCATTCGTTCATTGTTACTATTGTCGTTAGGTGGT-3′ (mutant ISRE element 2 probe antisense). The corresponding sense and antisense oligonucleotides were annealed to prepare the double-stranded DNA probes. The probes were end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 DNA polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen). The end-labeled probes (1 ng) were incubated with nuclear extracts (15 μg) in protein-DNA binding buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm DTT, 50 mm NaCl, 4% glycerol, and 0.05 mg/ml poly(dI-dC)·poly(dI-dC)) for 20 min at room temperature. For specificity controls, unlabeled WT probe was added to the reaction at a 1:100 molecular excess. DNA-protein complexes were separated by electrophoresis in 5% polyacrylamide gels in 45 mm Tris borate, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.3. The gels were dried and exposed to a phosphorimaging screen (Molecular Dynamics), and the images were acquired using a Strom 860 imager (Molecular Dynamics).

ABT-737 Therapy

4T1 cells (1 × 104 cells in 100 μl of Hanks' balanced salt solution) were injected orthotopically into the mammary fat pad on the mouse abdomen. ABT737 was dissolved in 30% propylene glycol, 5% Tween 80, and 65% D5W (5% dextrose in water) and injected intravenously into tumor-bearing mice at a dose of 20 mg/kg body weight at days 10, 13, 15, and 17 after tumor transplant. Mice were sacrificed 19 days after tumor transplant, and spleen cells were analyzed for MDSC apoptosis and % MDSCs as described above. Colon26 cells (5 × 105 cells in 100 μl of Hanks' balanced salt solution) were injected subcutaneously into the mouse right flank. ABT-737 was injected intravenously into the tumor-bearing mice at days 10, 13, and 16 after tumor transplant. Mice were sacrificed 19 days after tumor transplant, and spleen cells were analyzed for MDSC apoptosis and % MDSCs as described.

Statistical Analysis

To determine differences in MDSCs and apoptosis between control groups and the ABT 737 treatment groups and in FasL expression levels in CTLs between normal donors and cancer patients, a non-parametric Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.3, and statistical significance was assessed using an α level of 0.05. For all other analysis, Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided t test. Where indicated, data were represented as the means ±S.D. with p values<0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

MDSC Accumulation Is a Hallmark of Tumor Progression

MDSCs are a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells, and its differentiation is apparently tumor-dependent. Because of their heterogeneity and tumor dependence, we made use of two tumor models, the well established 4T1 mammary carcinoma (18) and the colon26 colon carcinoma (28). In the mammary carcinoma tumor model, analysis of subsets of immune cells validated that the percentages of MDSCs (CD11b+Gr1+ cells) were dramatically increased (supplemental Fig. S1, A and C), whereas the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (supplemental Fig. S1, B and C) was decreased. A generally similar pattern of immune cell profile was also observed in the Colon26 tumor model (supplemental Fig. S2, A–C).

Complete blood count with differential analysis also indicated that the numbers of white blood cell (WBC) subsets in the peripheral blood are dramatically changed in tumor-bearing mice as compared with tumor-free mice. Total WBC numbers were 5–10 times higher in the tumor-bearing mice than the tumor-free mice (supplemental Table S2). This dramatic increase is apparently due to the increase of neutrophils, which likely includes cells with MDSC phenotypes. The number of lymphocytes varied greatly between mice in both 4T1 and Colon26 tumor-bearing mice. However, no statistically significant changes in the number of lymphocytes were observed in both mouse tumor models (supplemental Table S2). Therefore, although the percentage of T cells was significantly decreased in tumor-bearing mice (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2), the total number of T cells was not changed significantly in tumor-bearing mice. Interesting, eosinophils disappeared in the peripheral blood of both 4T1 tumor- and Colon26 tumor-bearing mice (supplemental Table S2).

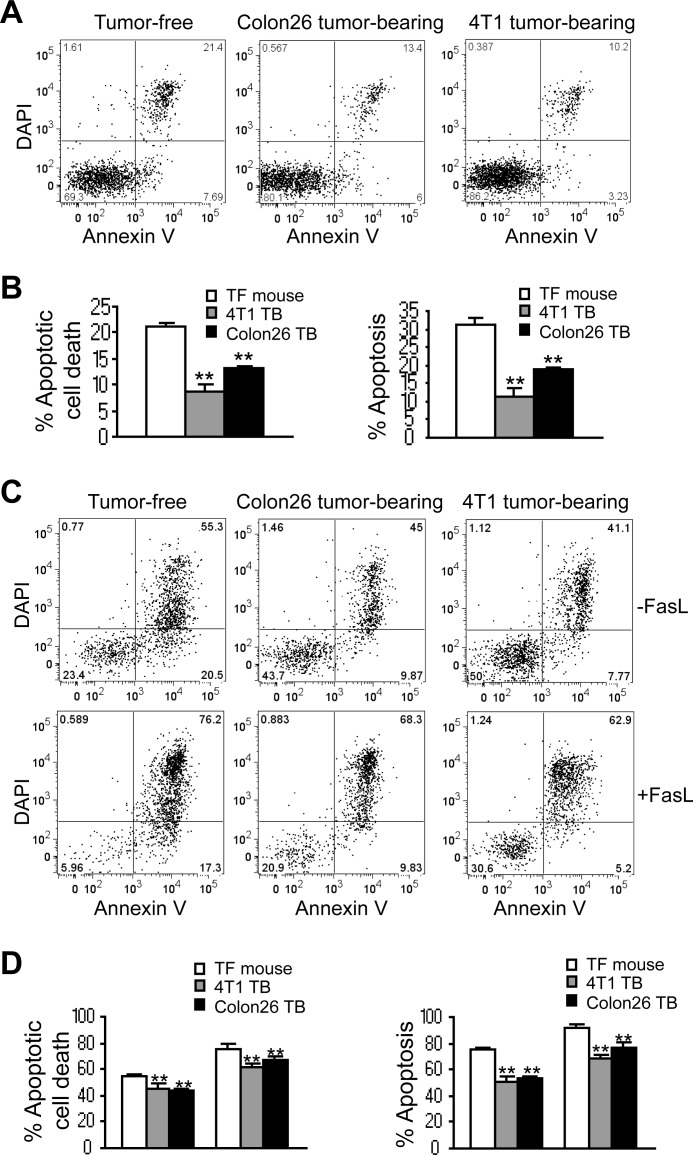

MDSCs Exhibit Decreased Spontaneous Apoptosis in Tumor-bearing Mice

It is well known that host CTLs eliminate autoreactive and unwanted T cells by the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway to mediate T cell hemostasis, and loss of Fas expression or function leads to accumulation of T cells and autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Recently, it has been shown that although MDSCs suppress T cell activation, T cells, once activated, eliminate MDSCs through inducing Fas-mediated apoptosis of MDSCs (35). However, it remains unclear how dominant this mechanism is in vivo given the fact that MDSCs persist. Therefore, we hypothesized that MDSCs might use deregulation of the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway to evade the host CTL-mediated apoptosis to persist in the tumor-bearing host in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we first analyzed MDSC spontaneous apoptosis. Spleen cells were collected from tumor-free and tumor-bearing mice and stained with CD11b- and Gr1-specific mAbs plus annexin V and DAPI. CD11b+Gr1+ MDSCs were gated and analyzed for annexin V+DAPI+ cells. MDSCs from 4T1 tumor-bearing mice exhibited significantly less spontaneous apoptosis as shown by the lower percentage of annexin V+DAPI+ (apoptotic cell death) and annexin V+ (apoptosis) cells as compared with control myeloid cells from tumor-free mice. A similar phenomenon was also observed in the Colon26 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 1, A and B). Our data thus indicate that decreased spontaneous apoptosis is a key feature of MDSCs.

FIGURE 1.

Tumor-induced MDSCs exhibit decreased spontaneous apoptosis in vivo. A and B, colon carcinoma Colon26 cells were surgically transplanted to the cecal wall of BALB/c mice to establish an orthotopic colon cancer mouse model. Mammary carcinoma 4T1 cells were injected to mammary fat pads of BALB/c mice to establish an orthotopic breast cancer mouse model. Spleen cells from tumor-free control mice (n = 5) and from tumor-bearing mice (n = 5 for each mouse model) were collected ∼30 days after tumor transplant and stained immediately under cold conditions with CD11b-, Gr1-specific mAbs, plus annexin V and DAPI. Stained live cells were analyzed immediately by flow cytometry. CD11b+Gr1+ cells were gated and analyzed for annexin V+ and DAPI+ cells. Shown are representative results of one of five mice for each tumor model. B, % apoptotic cell death was calculated as % CD11b+Gr1+annexinV+DAPI+ cells. % Apoptosis was quantified as % CD11b+Gr1+anexinV+ cells. Column, mean; bar, S.D. C and D, total spleen cells as described in A were cultured in the absence or presence of FasL in a 37 °C CO2 incubator for ∼24 h and analyzed for apoptosis as shown in A. D, quantification of apoptosis as shown in C.

To determine whether MDSCs from tumor-bearing mice exhibit decreased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis, total spleen cells were cultured in vitro in the absence or presence of FasL overnight. Cells were then stained with CD11b- and Gr1-specific mAbs plus annexin V and DAPI. CD11b+Gr1+ MDSCs were gated and analyzed for annexin V+DAPI+ cells. FasL induced a lesser degree of apoptosis in MDSCs from both 4T1 tumor- and Colon26 tumor-bearing mice as compared with tumor-free mice (Fig. 1, C and D). Our data thus indicate that tumor-induced MDSCs exhibit decreased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

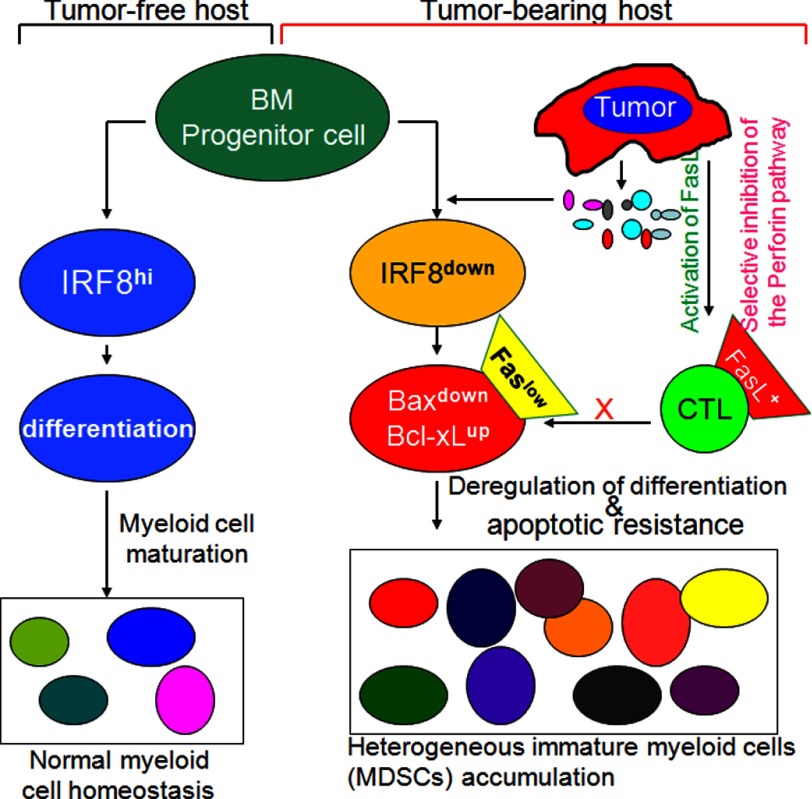

MDSCs Express Lower Level of Cell Surface Fas Receptor

Fas-mediated apoptosis initiates from the death receptor Fas. To elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms of decreased spontaneous apoptosis of MDSCs in the tumor-bearing host, we then analyzed Fas levels in MDSCs from tumor-free and 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that cell surface Fas protein level is significantly lower in MDSCs from tumor-bearing mice than those from tumor-free mice (Fig. 2A). Analysis of MDSCs from spleens of Colon26 tumor-bearing mice indicated that cell surface Fas protein level is also decreased as compared with CD11b+Gr1+ cells from tumor-free mice, albeit at a less degree (Fig. 2D). Taken together, our data indicate that down-regulation of Fas receptor is linked to decreased spontaneous apoptosis of MDSCs in tumor-bearing hosts.

FIGURE 2.

Deregulation of Fas, Bax, and Bcl-xL in MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice. A, cell surface Fas protein levels in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice are shown. Spleen cells were collected from tumor-free control (TF) and 4T1 tumor-bearing (TB) mice and stained with CD11b-, Gr1-, and Fas-specific mAbs. The stained cells were then analyzed for Fas protein level in gated CD11b+Gr1+ cells by flow cytometry. Shown is the representative image of one of three pairs of mice. The Fas mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was then quantified and presented at the bottom panel. Column, mean; bar, S.D. B, expression levels of Bcl-xL and Bax in MDSCs from 4T1 tumor-bearing mice are shown. MDSCs were purified from tumor-free (n = 3) and tumor-bearing (n = 3) mice. The expression levels of the indicated genes were analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (top panel) and real-time PCR (bottom panel). β-Actin was used as the normalization control in the real-time PCR. C, Bcl-xL and Bax protein levels in MDSCs from 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were analyzed by Western blotting. D, cell surface Fas protein levels in Colon26 tumor-bearing mice are shown. Spleen cells were collected from tumor-free control (TF) and Colon26 tumor-bearing (TB) mice and analyzed as in A. Shown is the representative image of one of three pairs of mice. The Fas mean fluorescence intensity was then quantified and presented at the right panel. Column, mean; bar, S.D. E, shown is quantitative analysis of Bcl-xL and Bax expression level in MDSCs. MDSCs were purified from tumor-free (n = 4) and Colon26 tumor-bearing (n = 3) mice. The mRNA levels of Bcl-xL and Bax were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR with β-actin as normalization controls.

Bax Is Down-regulated, and Bcl-xL Is Up-regulated in Tumor-induced MDSCs

Although Fas protein level is decreased in MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice, the Fas protein level is still relatively high. Therefore, it is unlikely that decreased Fas receptor (Fig. 2, A and D) alone accounts for the decreased spontaneous apoptosis of MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 1). We then analyzed expression levels of key mediators of the Fas-mediated apoptosis signaling pathways in MDSCs. RT-PCR analysis revealed that Bcl-xL level is dramatically increased and Bax level is dramatically decreased in MDSCs derived from 4T1 tumor-bearing mice as compared with myeloid cells with the same phenotypes from tumor-free mice (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the altered mRNA levels, Western blotting analysis determined that Bcl-xL protein level is also dramatically increased, whereas Bax protein level is dramatically decreased in MDSCs derived from tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 2C). Analysis of MDSCs from Colon26 tumor-bearing mice revealed that Bcl-xL is up-regulated and Bax is down-regulated as compared with myeloid cells with the same phenotypes from tumor-free mice (Fig. 2E). Our data thereby indicate that deregulation of multiple apoptosis-regulating genes, including the death receptor Fas, and downstream apoptosis mediators Bax and Bcl-xL is associated with decreased MDSC spontaneous apoptosis in tumor-bearing hosts.

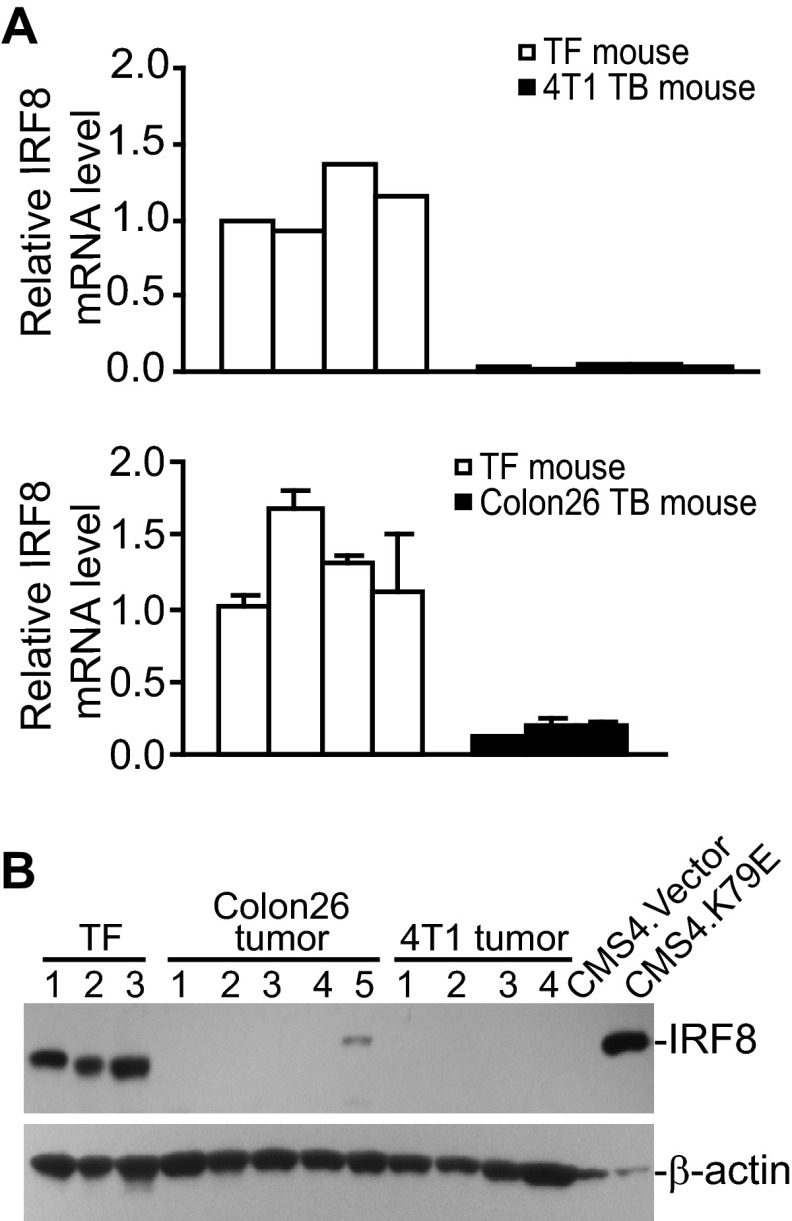

IRF8 Is Down-regulated in Tumor-induced MDSCs in Vivo

The molecular mechanisms underlying altered Fas, Bcl-xL, and Bax expression in MDSCs is not clear. A previous study has shown that Bcl-xL expression is regulated by IRF8 in myeloid leukemia cell lines (43), and our previous study has shown that Bax and Fas are transcriptionally regulated by IRF8 in myeloid cells and in non-hematopoietic cells (40, 44). We, therefore, reasoned that altered expression of Fas, Bax, and Bcl-xL might be due to altered IRF8 expression in MDSCs. Indeed, IRF8 is highly expressed in myeloid cells from tumor-free mice, and both IRF8 mRNA (Fig. 3A) and protein (Fig. 3B) became undetectable in MDSCs derived from Colon26 and 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. Together, our data suggest that altered expression of Bax, Fas, and Bcl-xL is associated with IRF8 down-regulation in MDSCs of tumor-bearing mice.

FIGURE 3.

IRF8 Expression is silenced in tumor-induced MDSCs in vivo. A, IRF8 expression levels in MDSCs from 4T1 tumor (top panel)- and Colon26 tumor (bottom panel)-bearing mice are shown. MDSCs were purified from tumor-free control (TF, n = 4 for each tumor model), 4T1 tumor-bearing (TB, n = 5), and Colon26 tumor-bearing (TB, n = 3) mice and analyzed by real-time RT-PCR for IRF8 mRNA levels with β-actin as normalization controls. B, MDSCs from tumor-free, Colon26 tumor-bearing (n = 5), and 4T1 tumor-bearing (n = 4) mice were also analyzed by Western blotting for IRF8 protein levels. CMS4.Vector and CMS4.K79E cells were used here as IRF8 protein controls.

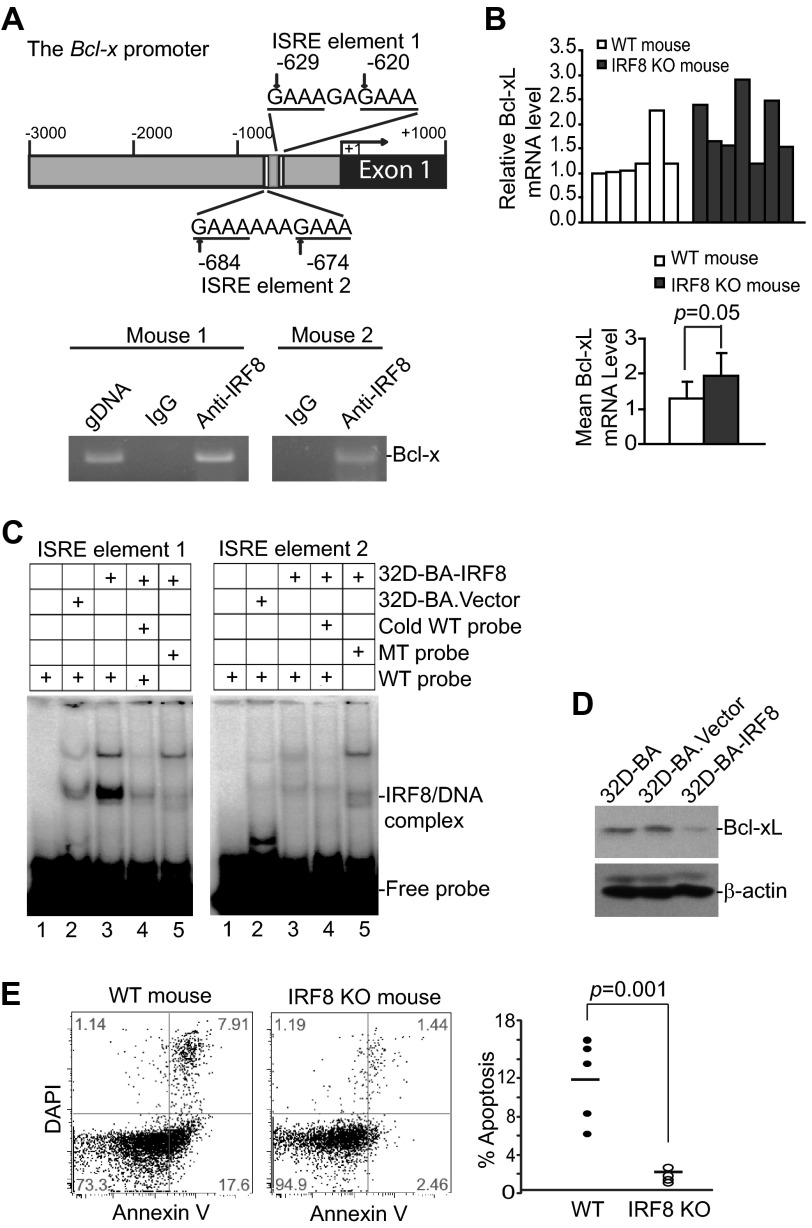

IRF8 Represses Bcl-xL Expression

Our previous study has shown that IRF8 directly bind to the Bax gene promoter in mouse primary myeloid cells to activate Bax transcription (40). To determine whether IRF8 directly regulates Bcl-x transcription in myeloid cells, we analyzed Bcl-x promoter DNA sequence and identified two ISREs, a IRF8 binding consensus sequence that is often associated with transcriptional repression when bound by IRF8, in the mouse Bcl-x promoter region (Fig. 4A). ChIP analysis of purified myeloid cells showed that IRF8 is associated with the chromatin in the ISRE region of the Bcl-x promoter in primary myeloid cells (Fig. 4A). RT-PCR analysis revealed that Bcl-xL expression levels in MDSC-like cells of the spleens are relatively uniform in five of the six WT control mice. The Bcl-xL expression levels in MDSC-like cells of the spleens are relatively variable in IRF8 KO mice with higher Bcl-xL levels in three of seven mice analyzed (Fig. 4B). Statistical analysis of Bcl-xL expression levels indicates that the overall Bcl-xL expression level is higher in MDSC-like cells of WT control mice group than that of the IRF8 KO mouse group (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

IRF8 is a transcriptional repressor of Bcl-xL. A, IRF8 binds to the Bcl-x promoter in primary myeloid cells. Top panel, shown is the mouse Bcl-x gene promoter structure. The locations of two ISRE elements are indicated. Bottom panel, ChIP analysis of IRF8 binding to the Bcl-x promoter in CD11b+ myeloid cells is shown. Genomic DNA was used as a positive control for PCR. B, analysis of mouse Bcl-xL mRNA levels in CD11b+ myeloid cells from wild type (n = 6) and IRF8 KO mice (n = 7) is shown by real-time RT-PCR. β-Actin was used as the normalization control. The relative Bcl-xL mRNA levels in WT and IRF8 KO mice were averaged and are presented in the bottom panel. C, DNA probes that contain ISRE sequences as shown in A were incubated with nuclear extracts from 32D-BA.Vector and 32D-BA.IRF8 cells as indicated. Mutant probes and cold probe competition were included as specificity controls. The protein-DNA complexes were analyzed by non-denatured polyacrylamide gel. D, the indicated myeloid cells were analyzed for Bcl-xL protein levels by Western blotting analysis. E, shown is spontaneous apoptosis of spleen cells in WT and IRF8 KO mice. Spleen cells were stained with CD11b- and Gr1-specific mAb plus annexin V and DAPI and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are representative images of one pair of five pairs of mice (left two panels). Apoptosis was quantified in gated MDSCs as % annexin V+ DAPI+ cells and is presented in the right panel. Each dot represents % apoptosis of MDSCs from one mouse.

A complementary approach was then used to validate IRF8 binding to the ISRE sequences of the mouse Bcl-x gene promoter. Oligonucleotides of the ISRE element-containing region of the Bcl-x gene promoter were synthesized to prepare double-stranded DNA probes. Nuclear extracts were prepared from the immortalized myeloid precursor 32D cells that overexpress IRF8 (32D-BA.IRF8) and the vector control cells (32D-BA.Vector, as an IRF8 negative control) (39). Probes with mutated ISRE consensus sequences were used as specificity control. Analysis of DNA-protein interactions by EMSA indicated that IRF8 binds to the ISRE element 1 but not the ISRE element 2 in vitro (Fig. 4C). These observations thus validate the above in vivo ChIP data and indicate that IRF8 binds to at least one of the two ISRE elements in the mouse Bcl-x promoter region in myeloid cells. At the functional level, Western blotting analysis showed that overexpression of IRF8 represses Bcl-xL expression in myeloid cells (Fig. 4D).

The above observations thus suggest that loss of IRF8 expression might be the cause of increased Bcl-xL expression that is responsible, at least in part, for the decreased MDSC apoptosis and increased MDSC persistence in tumor-bearing mice. Indeed, one of the hallmarks of IRF8 KO mice is accumulation of CD11b+Gr1+ MDSC-like cells (40, 45, 46); we then examined spontaneous apoptosis of spleen CD11b+Gr1+ cells from IRF8 KO and WT control mice. MDSC-like cells from IRF8 KO mice exhibited significantly less spontaneous apoptosis as compared with WT mice (Fig. 4E). Thus, our data suggest that IRF8 functions as a transcription repressor of Bcl-xL and transcription activator of Bax in myeloid cells, and CD11b+Gr1+ MDSC-like cells in IRF8 KO mice might use down-regulation of IRF8 to alter Bcl-xL and Bax expression levels to decrease their sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

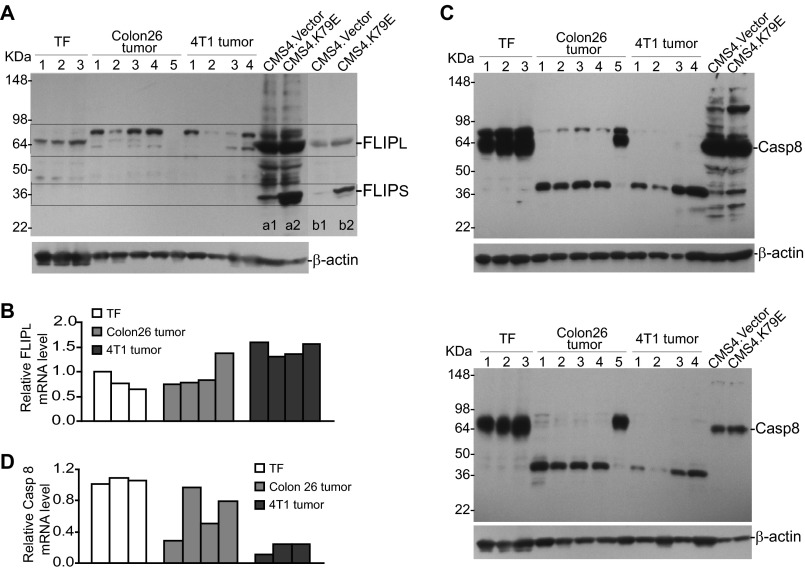

FLIP and Caspase 8 Expression in Tumor-induced MDSCs

FLIP and caspase 8 are key mediators of the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway (47–49). Up-regulation of FLIP and down-regulation of caspase 8 are often observed in cancer cells. We then analyzed FLIP and caspase 8 levels in tumor-induced MDSCs. RT-PCR and Western blotting analysis indicated that FLIPs are undetectable in MDSCs. Western blotting analysis revealed the existence of three polypeptides with similar molecular weights as FLIPL that are reactive to a FLIP-specific antibody in tumor-induced MDSCs from both 4T1 and Colon26 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 5A). CMS4.K79E is a sarcoma cell line that overexpresses a dominant-negative IRF8 mutant with resultant up-regulation of FLIPs and, therefore, was used here as a FLIP-positive control. Real-time RT-PCR analysis indicated that FLIPL mRNA is up-regulated in MDSCs from only one of the four Colon26 tumor-bearing mice as compared with MDSCs from tumor-free mice. However, FLIPL is up-regulated in MDSCs from all four 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 5B). Pro-caspase 8 protein level is high in MDSCs from tumor-free mice and dramatically decreased in MDSCs from both tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 5C). A polypeptide with smaller size was detected in tumor-induced MDSCs but not in MDSCs from tumor-free mice (Fig. 5C). Two caspase 8-specific antibodies were used, and similar protein patterns were observed (Fig. 5C). Real-time RT-PCR analysis indicated that caspase 8 mRNA levels are lower in MDSCs from two of the four mice as compared with MDSCs from tumor-free mice. However, caspase 8 mRNA levels are lower in MDSCs from all three 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 5.

FLIP and caspase 8 expression levels in tumor-induced MDSCs. A, MDSCs were purified from spleen cells of tumor-free (TF; n = 3), Colon26 tumor-bearing (n = 5), and 4T1 tumor-bearing (n = 4) mice and analyzed for FLIP protein levels. CMS4.Vector and CMS4.K79E cells were used here as FLIP protein-positive controls. Lanes b1 and b2 are lighter exposed images of lanes a1 and a2. The locations of FLIPs and FLIPL are indicated based on the positive controls. B, MDSCs were purified from the spleens of the indicated mice as in A and analyzed for FLIPL mRNA levels by real-time RT-PCR. β-Actin was used as the normalization control. C, MDSCs were purified as in A and analyzed for caspase 8 protein levels using a rabbit anti-mouse caspase 8 antibody (AF1650, top panel) and a goat anti-mouse caspase 8 (AF705, bottom panel) antibody, respectively. CMS4.Vector and CMS4.K79E cells were used as Casp8 protein positive controls. D, MDSCs were purified from the spleens of the indicated mice as in A and analyzed for caspase 8 mRNA levels by real-time RT-PCR with β-actin as normalization controls.

FasL Is Up-regulated in Tumor-infiltrating CTLs in Tumor-bearing Mice and in Human Cancer Patients

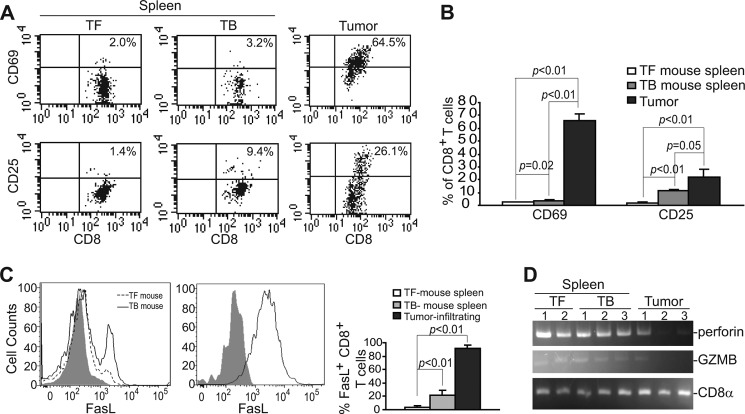

To determine the activation status of CTLs, we first analyzed CD8+ cells using CD69 and CD25 as activation markers. As expected, spleen CD8+ T cells from tumor-free control mice are quiescent and are essentially CD25− and CD69−. The percentage of CD69+ spleen CD8+ T cells increased slightly, and the percentage of CD25+ spleen CD8+ T cells also increased in the 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 6, A and B). Interestingly, ∼65% tumor-infiltrating CTLs are CD69+, and 26% tumor-infiltrating CTLs are CD25+ (Fig. 6, A and B). Our data thus indicate that CTLs are partially activated in the tumor microenvironment.

FIGURE 6.

FasL is up-regulated in tumor-infiltrating CTLs. A, shown is the activation status of CTLs. Spleen cells from tumor-free (TF, n = 3) and 4T1 tumor-bearing (TB, n = 3) mice and tumors were stained for CD25 and CD69 levels on CTLs by flow cytometry. CD8+ T cells were gated and analyzed for CD25 and CD69. Shown are representative images of one of three mice. B, the percentage of CD25+/CD69+ CD8+ T cells as shown in A was quantified and presented. C, spleen cells from tumor-free control (n = 3) and 4T1 tumor-bearing (n = 3) mice and tumors were stained with CD8- and FasL-specific mAbs. CD8+ cells were then gated and analyzed for FasL+ cells by flow cytometry. The percentage of FasL+ CD8+ T cells were quantified and presented in the right panel. D, shown is activation status of the perforin cytotoxic pathway. CD8+ T cells were isolated from spleen cells of tumor-free and 4T1 tumor-bearing mice and tumors and analyzed for the expression levels of perforin and granzyme B (GZMB) by RT-PCR. CD8α was used as normalization control.

We then examined FasL levels in CD8+ T cells. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that, consistent with the quiescent status, CD8+ T cells in spleens of tumor-free mice express no cell surface FasL. However, a portion of CD8+ T cells in spleens of the tumor-bearing mice are FasL+ (Fig. 6C). Again, consistent with the activation status, the majority of tumor-infiltrating CTLs are FasL+ (Fig. 6C). Surprisingly, analysis of key mediators of the perforin cytotoxic pathway revealed that granzyme A was undetectable, and levels of perforin and granzyme B were not increased in the tumor-infiltrating CTLs as compared with quiescent CD8+ T cells in tumor-free mice (Fig. 6D).

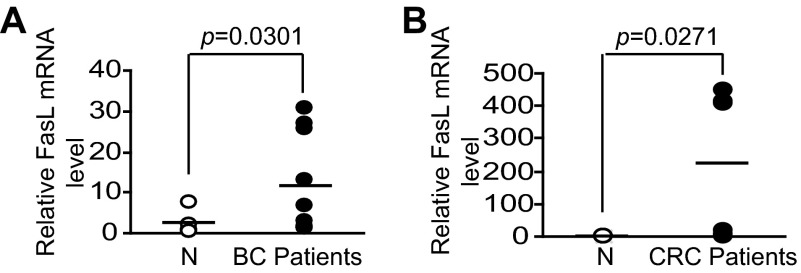

We next sought to determine whether FasL is up-regulated in CTLs from human cancer patients. Blood specimens were collected from healthy donors, breast, and colorectal cancer patients. CD8+ T cells were purified from the blood specimens and analyzed for FasL mRNA levels. Real-time RT-PCR analysis revealed that FasL mRNA levels are significantly higher in CTLs from both breast (Fig. 7A) and colorectal (Fig. 7B) cancer patients than that in CTLs from healthy donors. Taken together, our data demonstrated that FasL is up-regulated in CTLs in both tumor-bearing mice and in human breast and colorectal cancer patients, suggesting that immune suppression might not suppress FasL up-regulation of tumor-reactive CTLs in tumor-bearing hosts.

FIGURE 7.

FasL expression is up-regulated in CTLs of human cancer patients. Peripheral blood was collected from normal donors (N), human breast (BC patients, A), and colorectal (CRC patients, B) cancer patients. CD8+ T cells were isolated for RNA preparation. FasL mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR using CD8a as normalization controls.

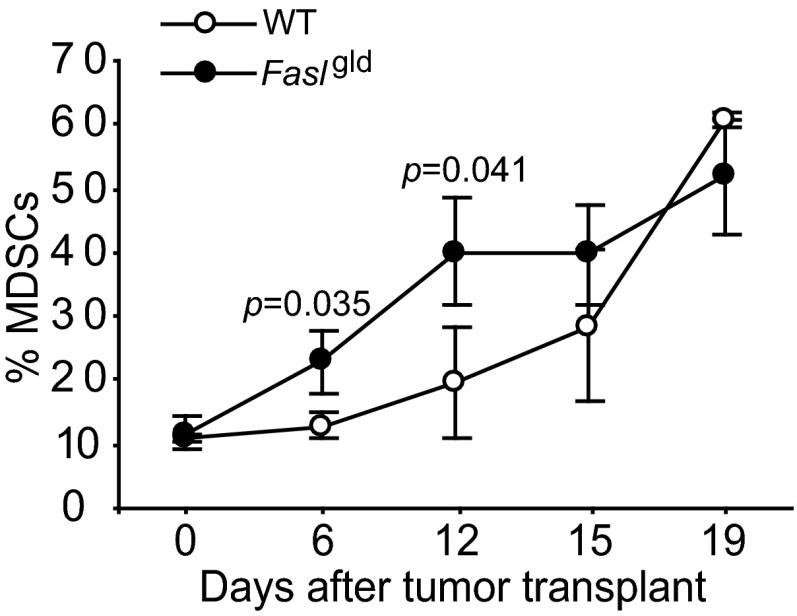

Fas-FasL Interaction Suppresses MDSC Persistence in Vivo

The observations that MDSCs express Fas receptor (Fig. 2) and tumor-infiltrating CTLs are FasL+ (Figs. 6 and 7) suggest that, like T lymphocyte homeostasis, Fas-FasL interactions might mediate MDSC turnover. To test this hypothesis, 4T1 tumors were transplanted to WT and Faslgld mice, and MDSCs were analyzed in the peripheral blood of tumor-bearing mice over time. Significantly more MDSCs were detected in the tumor-bearing Faslgld mice than in the tumor-bearing WT mice at the early stage of tumor development (Fig. 8). However, no significant difference in MDSCs was observed at the late stage of tumor development (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Fas-FasL interaction mediates MDSCs homeostasis. 4T1 tumor cells were injected to WT control (n = 3) and Faslgld (n = 3) mice. Blood was collected at the indicated time points and analyzed for CD11b+Gr1+ MDSCs over time.

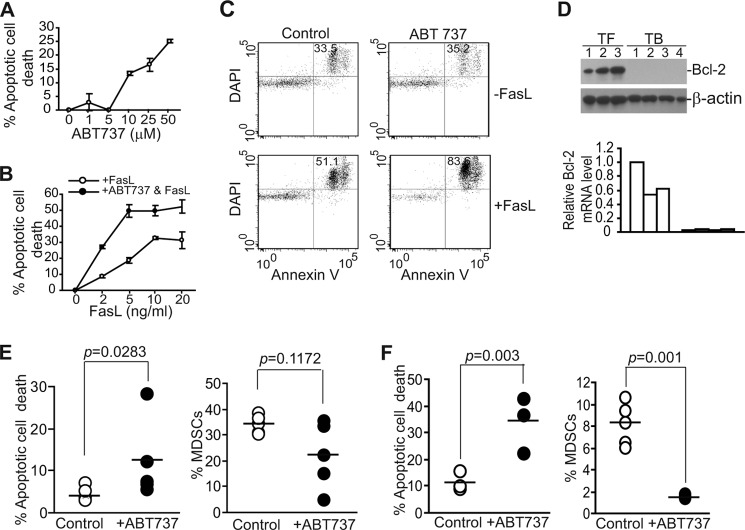

Inhibition of Bcl-xL Activity Increases MDSC Sensitivity to Fas-mediated Apoptosis in Vitro

Our data above suggest that up-regulation of Bcl-xL is responsible, at least in part, for the decreased sensitivity of tumor-induced MDSCs to Fas-mediated apoptosis. We then reasoned that inhibition of Bcl-xL activity should increase MDSC sensitivity to apoptosis induction. To test this hypothesis, we made use of ABT-737, a potent inhibitor of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-w (50) and observed that ABT-737 alone showed significant cytotoxicity toward MDSCs in a dose-dependent manner in vitro (Fig. 9A). We then used a sublethal dose of ABT-737 (5 μm) that alone does not induce significant apoptosis of MDSCs and tested its sensitization effects. Although MDSCs were sensitive to high concentrations of FasL in vitro (Fig. 9B), a sublethal dose of ABT-737 significantly increased MDSC sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis in vitro (Fig. 9, B and C). Because ABT-737 also targets Bcl-2, we analyzed Bcl-2 expression level in MDSCs. Bcl-2 protein and mRNA levels were relatively high in MDSCs from tumor-free mice but were surprisingly undetectable in the 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 9D).

FIGURE 9.

Pharmacologic inhibition of Bcl-xL activity increases spontaneous MDSC apoptosis to suppress MDSC accumulation in vivo. A, ABT-737 cytotoxicity to MDSCs is shown. Total spleen cells were cultured in the presence of different doses of ABT-737 for ∼16 h. Cells were then stained with CD11b- and Gr1-specific mAbs plus annexin V. CD11b+Gr1+ cells were gated and analyzed for annexin V+ cells. % apoptosis was calculated by the formula: % CD11b+Gr1+annexinV+ cells in the presence of ABT-737 − % CD11b+Gr1+annexinV+ cells in the absence of ABT-737. B, total spleen cells were cultured in the absence or presence of a sublethal dose of ABT737 (5 μm) and various concentrations of FasL as indicated for ∼16 h and analyzed for apoptosis as in A. Shown are representative results of one of two independent experiments. C, a sublethal dose of ABT-737 increased MDSC sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Total spleen cells were cultured in the absence or presence of a sublethal dose of ABT737 (5 μm) and FasL (10 ng/ml) for ∼16 h and analyzed for apoptosis as in B. Shown are representative plots of one of two independent experiments. D, shown are Bcl-2 expression levels in MDSCs. MDSCs were purified from tumor-free (TF, n = 3) and 4T1 tumor-bearing (TB, n = 4) mice and analyzed for Bcl-2 protein level by Western blotting. E, ABT-737 increased MDSC spontaneous apoptosis and decreased MDSC accumulation in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. 4T1 cells were injected to mouse mammary pat pad. Tumor-bearing mice were either untreated (n = 5) or treated with ABT737 (n = 5) injected intravenously as described under “Materials and Methods.” Spleen cells from untreated and treated mice were analyzed for CD11b+Gr1+annexin V+DAPI+ cells (left panel) and % MDSCs of total spleen cells (right panel). Each dot represents % apoptotic MDSCs (left panel) or % total MDSCs (right panel) of one mouse. F, ABT-737 increased MDSC spontaneous apoptosis and decreased MDSC accumulation in Colon26 tumor-bearing mice. Colon26 cells were injected to mice subcutaneously. Tumor-bearing mice were either untreated (n = 5) or treated with ABT737 (n = 3) injected intravenously as described under “Materials and Methods.” Spleen cells from untreated and treated mice were analyzed for CD11b+Gr1+annexin V+DAPI+ cells (left panel) and % MDSCs of total spleen cells (right panel). Each dot represents % apoptotic MDSCs (left panel) or % MDSCs (right panel) of one mouse.

ABT-737 Increases MDSCs Apoptosis and Suppresses MDSCs Persistence in Vivo

Our above data demonstrated that ABT-737 can effectively increase MDSC sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis in vitro (Fig. 9C). We then reasoned that ABT-737 should sensitize MDSCs to CTL-exerted and Fas-mediated apoptosis as tumor-infiltrating CTLs are FasL+ and thereby increase MDSC apoptosis to decrease MDSC persistence in tumor-bearing mice. To test this hypothesis, 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were treated with ABT-737 and analyzed for MDSC apoptosis and accumulation. Indeed, ABT-737 therapy significantly increased MDSC spontaneous apoptosis in vivo in the 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (p = 0.0283) (Fig. 9E) and resulted in decreased MDSC accumulation in three of the five mice in the treatment group (Fig. 9E). In the Colon26 tumor-bearing mice, ABT-737 therapy also significantly increased MDSC spontaneous apoptosis and decreased MDSC accumulation in all mice in the treatment group (Fig. 9F). Taken together, our data indicate that targeting Bcl-xL with a sublethal dose of ABT-737 is an effective strategy for suppression of MDSCs accumulation in the tumor-bearing host.

DISCUSSION

Two distinct, yet interlinked signaling pathways control mammalian cell apoptosis (51). The intrinsic apoptosis signaling pathway is activated by intracellular signals, such as DNA damage, whereas the extrinsic apoptosis signaling pathways are usually activated by engagement of death receptors by cytotoxic cells of the immune system under physiological conditions (52). The death receptor Fas and its physiological ligand FasL mediate the extrinsic apoptosis signaling pathways. Binding to Fas by FasL triggers receptor trimerization followed by formation of death-inducing signaling complex and subsequent apoptosis (53). Germ line and somatic mutations or deletions of Fas or FasL gene-coding sequences in humans lead to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (54, 55), suggesting a critical role of the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway in elimination of unwanted T cells and in lymphocytes homeostasis. It was recently shown that T cells, once activated, eliminate MDSCs through inducing Fas-mediated apoptosis (35). Thus, it seems that the host T cells might also use the Fas-FasL system to eliminate MDSCs. However, MDSCs still persist in the tumor-bearing mice despite FasL+ T cell activation (Fig. 6C). In this study we observed that tumor-induced MDSCs exhibited decreased cell surface Fas protein levels. Furthermore, the level of pro-apoptotic Bax is decreased, and the anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL level is increased in MDSCs of tumor-bearing mice. It is known that loss of Bax function leads to resistance to death receptor-mediated apoptosis (56), and increased Bcl-xL levels have been liked to myeloid leukemia apoptosis resistance (43). Consistent with the altered Fas, Bax, and Bcl-xL levels, MDSCs from tumor-bearing mice exhibited an increased apoptotic resistance phenotype, and inhibition of Bcl-xL activity with ABT-737 significantly increased MDSCs sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis in vitro. Our data thus suggest that deregulation of the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway confers MDSC increased apoptotic resistance to evade the host CTL-mediated elimination in the tumor-bearing hosts, suggesting that, like T cells in autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, deregulation of the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway is an underlying mechanism for MDSC persistence.

Caspase-8 plays a critical role in activating the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathways, and its expression is often altered in cancer cells via multiple mechanisms, including genetic alterations, epigenetic modifications, alternative splicing, or posttranslational modifications (57, 58). In this study we observed that although its mRNA levels are variable, the procaspase 8 protein levels are dramatically lower in MDSCs from tumor-bearing mice as compared with MDSCs from tumor-free mice. However, a short form of protein band was detected in MDSCs from tumor-bearing mice, and this band was detected by two different caspase 8-specific antibodies, suggesting that this protein might be a truncated form of procaspase 8 (58, 59) which requires further investigation.

On the other hand, caspase 8 inhibitory FLIP proteins play an important role in suppressing Fas-mediated apoptosis, and its expression is often up-regulated in cancer cells (57, 60, 61). Several FLIP variants, notably FLIPL, FLIPS, and FLIPR, have been observed (60), and their concentrations at the moment when the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) is formed determines the outcome of the DISC signal. FLIP proteins are subject to dynamic turnover, and their stability and expression levels can be rapidly altered (49). The function of FLIPS as an inhibitor of Fas-mediated apoptosis is well established; however, the functions of FLIPL in apoptosis remain controversial (62). In a previous study we observed that overexpression of a dominant-negative IRF8 mutant results in up-regulation of FLIPS and increased resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis in sarcoma cells, whereas IRF8 KO primary myeloid cells exhibit increased FLIPL protein levels (63). In this study we observed that FLIPS mRNA and protein are undetectable in MDSC cells from both tumor-free and tumor-bearing mice. FLIPL mRNA is detectable in MDSCs from both tumor-free and tumor-bearing mice. However, the FLIPL protein banding patterns in MDSCs are different between tumor-free and tumor-bearing mice, with three distinct bands in MDSCs from tumor-bearing mice. These bands with subtle molecular weight differences are potentially FLIPL proteins with different post-translational modifications or alternative splicing, which remain to be determined.

IRF8 is a key transcription factor that mediates myeloid lineage differentiation (64) and is linked to tumor-induced MDSC accumulation (65). In a previous study, we showed that IRF8 directly activates Bax transcription in primary myeloid cells (40). Here, we demonstrated that IRF8 functions as a transcription repressor of Bcl-xL in primary myeloid cells and myeloid precursor cells. However, the expression levels of Bcl-xL in MDSC-like cells in the IRF8 KO mice vary greatly among mice. It is known that the CD11b+Gr1+ MDSC phenotype-like cells in IRF8 KO mice are a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells that resembles human chronic myelogenous leukemia cells, and the phenotype of these cells changes with age with ∼10% mice progress to develop a fatal blast crisis (45). Although tumor-induced MDSCs and MDSC-like cells in IRF8 KO mice are phenotypically similar, it remains to be determined whether they are functionally similar. Therefore, it is possible that only a portion of the MDSC-like cells in IRF8 KO mice are actually MDSCs and the compositions of these MDSC subpopulation change with mouse age, which may explain the variable Bcl-xL expression level in MDSC-like cells in IRF8 KO mice. Nevertheless, our data suggest that tumor-induced MDSCs might decrease IRF8 expression to down-regulate Bax and to up-regulate Bcl-xL expression in vivo.

The observation that tumor-infiltrating CTLs are FasL+ in both tumor-bearing mice and human cancer patients is a very interesting one as MDSCs are potent immune-suppressive cells that account for the majority of immune cells in the tumor-bearing hosts (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). It has been shown previously that although Treg cells can inhibit clonal expansion of activated T cells in vitro, Treg cells do not inhibit CD8+ T cell activation and proliferation in vivo but rather selectively inhibit granule exocytosis of CTLs, thereby selectively impairing the perforin effector mechanism of CTLs (66, 67). Our data suggest that MDSCs might not inhibit up-regulation of FasL of CTLs in tumor-bearing mice and human cancer patients. Based on these observations, we propose a model for MDSC apoptosis resistance and persistence in vivo (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10.

Model of apoptotic resistance and MDSC persistence in vivo. IRF8 is highly expressed in myeloid progenitor cells from the bone marrow (BM) to regulate myeloid cell differentiation. Tumor cells secrete inflammatory mediators to decrease IRF8 expression. Loss of IRF8 expression results in blockage of normal myeloid cell differentiation and altered Bax and Bcl-xL expression in the immature myeloid cells to confer MDSCs with increased resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis, resulting in escape of MDSCs from CTL-mediated and FasL-dependent elimination to persist.

It has also been shown that Treg cells are sensitive, whereas activated effector CTLs are resistant, to CTL-mediated and FasL-induced apoptosis (68). Similarly, FasL of CTLs has been shown to induce apoptosis in MDSCs but not in other normally differentiated myeloid cells (35). Therefore, FasL+ tumor-specific CTLs might be exploited to induce apoptosis of both immune-suppressive cells, including Treg cells and MDSCs, and tumor cells through the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway to achieve effective tumor suppression in the immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment in cancer immunotherapy.

Due to their potent immune suppressive activity, MDSCs are considered a major obstacle in cancer immunotherapy. Therefore, extensive effects have been devoted to suppress MDSCs to increase the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy (69–74). Most of the current efforts in development of therapeutic agents primarily focused on targeting MDSCs proliferation (69–74). In this study we revealed that acquisition of increased apoptosis resistance is a key feature of MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice, suggesting that targeting apoptosis resistance is a complimentary approach to suppress MDSCs in tumor-bearing hosts. Furthermore, we have identified Bcl-xL as a molecular target for targeting MDSC apoptotic resistance. Our data showed that targeting Bcl-xL with ABT-737 increases MDSC sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis. Although ABT-737 alone can effectively induce MDSC apoptosis, high doses of chemotherapy is often toxic. Our data indicate that a sublethal dose of ABT-737 is potentially effective as a sensitizer to increase MDSC sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis. We should point out here that ABT-737 targets not only Bcl-xL, but also Bcl-2 and Bcl-w (50), and it has recently been shown that Bcl-2 is a better target of ABT-737 than Bcl-xL (75). In this study, we surprisingly observed that Bcl-2 is highly expressed in MDSCs of tumor-free mice but is down-regulated in MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice. The role of IRF8 in regulation of Bcl-2 is controversial. It has been shown that IRF8 represses Bcl-2 expression in myeloid cells in vitro (39). However, it has also been shown that IRF8 does not regulate Bcl-2 expression in myeloid cells in vivo (76). In our study the IRF8 expression level is inversely correlated with Bcl-2 expression level in tumor-induced MDSCs. Although the relationship between IRF8 and Bcl-2 in MDSCs remains to be determined in tumor-induced MDSCs, our data indicated that Bcl-xL is likely a primary target of ABT-737 in MDSCs in the tumor-bearing mice, as Bcl-2 is not expressed in tumor-induced MDSCs. Therefore, ABT-737 may be used at a sublethal dose to effectively sensitize MDSCs to host CTL-induced apoptosis without apparent toxicity and thus holds great promise for further development as an adjunct agent to increase the efficacy of CTL-based cancer immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Brenda Rosson, Julia Jordan, and Candelario Laserna in the Surgical Research Service at Georgia Regents Medical Center for consenting and assisting with blood specimen collection from human cancer patients, Sameera Qureshi at the Georgia Regents University Tumor Bank for blood specimen collection, and Stephanie Barnett at Augusta Shepeard Community Blood Center for consenting and collecting blood samples from normal healthy donors.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA133085, CA168512-DRP1 (to K. L.), and CA140622 (to S. I. A.). This work was also supported by American Cancer Society Grant RSG-09209 (to K. L.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- MDSC

- myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- CTL

- cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- ISRE

- interferon-stimulated response element.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ostrand-Rosenberg S. (2010) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. More mechanisms for inhibiting antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 59, 1593–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gabrilovich D. I., Ostrand-Rosenberg S., Bronte V. (2012) Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 253–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Srivastava M. K., Andersson Å., Zhu L., Harris-White M., Lee J. M., Dubinett S., Sharma S. (2012) Myeloid suppressor cells and immune modulation in lung cancer. Immunotherapy 4, 291–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saleem S. J., Martin R. K., Morales J. K., Sturgill J. L., Gibb D. R., Graham L., Bear H. D., Manjili M. H., Ryan J. J., Conrad D. H. (2012) Cutting edge. Mast cells critically augment myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity. J. Immunol. 189, 511–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haile L. A., Gamrekelashvili J., Manns M. P., Korangy F., Greten T. F. (2010) CD49d is a new marker for distinct myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations in mice. J. Immunol. 185, 203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nagaraj S., Youn J. I., Weber H., Iclozan C., Lu L., Cotter M. J., Meyer C., Becerra C. R., Fishman M., Antonia S., Sporn M. B., Liby K. T., Rawal B., Lee J. H., Gabrilovich D. I. (2010) Anti-inflammatory triterpenoid blocks immune suppressive function of MDSCs and improves immune response in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 1812–1823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pilon-Thomas S., Nelson N., Vohra N., Jerald M., Pendleton L., Szekeres K., Ghansah T. (2011) Murine pancreatic adenocarcinoma dampens SHIP-1 expression and alters MDSC homeostasis and function. PLoS ONE 6, e27729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fortin C., Huang X., Yang Y. (2012) NK cell response to vaccinia virus is regulated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J. Immunol. 189, 1843–1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Srivastava M. K., Zhu L., Harris-White M., Kar U. K., Kar U., Huang M., Johnson M. F., Lee J. M., Elashoff D., Strieter R., Dubinett S., Sharma S. (2012) Myeloid suppressor cell depletion augments antitumor activity in lung cancer. PLoS ONE 7, e40677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Solito S., Falisi E., Diaz-Montero C. M., Doni A., Pinton L., Rosato A., Francescato S., Basso G., Zanovello P., Onicescu G., Garrett-Mayer E., Montero A. J., Bronte V., Mandruzzato S. (2011) A human promyelocytic-like population is responsible for the immune suppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood 118, 2254–2265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gabrilovich D. I., Nagaraj S. (2009) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 162–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ryzhov S., Novitskiy S. V., Goldstein A. E., Biktasova A., Blackburn M. R., Biaggioni I., Dikov M. M., Feoktistov I. (2011) Adenosinergic regulation of the expansion and immunosuppressive activity of CD11b+Gr1+ cells. J. Immunol. 187, 6120–6129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramachandran I. R., Martner A., Pisklakova A., Condamine T., Chase T., Vogl T., Roth J., Gabrilovich D., Nefedova Y. (2013) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells regulate growth of multiple myeloma by inhibiting T cells in bone marrow. J. Immunol. 190, 3815–3823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mace T. A., Ameen Z., Collins A., Wojcik S., Mair M., Young G. S., Fuchs J. R., Eubank T. D., Frankel W. L., Bekaii-Saab T., Bloomston M., Lesinski G. B. (2013) Pancreatic cancer-associated stellate cells promote differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in a STAT3-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 73, 3007–3018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murdoch C., Muthana M., Coffelt S. B., Lewis C. E. (2008) The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 618–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ostrand-Rosenberg S., Sinha P. (2009) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Linking inflammation and cancer. J. Immunol. 182, 4499–4506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Condamine T., Gabrilovich D. I. (2011) Molecular mechanisms regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation and function. Trends Immunol. 32, 19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sinha P., Okoro C., Foell D., Freeze H. H., Ostrand-Rosenberg S., Srikrishna G. (2008) Proinflammatory S100 proteins regulate the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J. Immunol. 181, 4666–4675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song X., Krelin Y., Dvorkin T., Bjorkdahl O., Segal S., Dinarello C. A., Voronov E., Apte R. N. (2005) CD11b+Gr1+ immature myeloid cells mediate suppression of T cells in mice bearing tumors of IL-1β-secreting cells. J. Immunol. 175, 8200–8208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bunt S. K., Yang L., Sinha P., Clements V. K., Leips J., Ostrand-Rosenberg S. (2007) Reduced inflammation in the tumor microenvironment delays the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and limits tumor progression. Cancer Res. 67, 10019–10026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rodriguez P. C., Hernandez C. P., Quiceno D., Dubinett S. M., Zabaleta J., Ochoa J. B., Gilbert J., Ochoa A. C. (2005) Arginase I in myeloid suppressor cells is induced by COX-2 in lung carcinoma. J. Exp. Med. 202, 931–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cheng P., Corzo C. A., Luetteke N., Yu B., Nagaraj S., Bui M. M., Ortiz M., Nacken W., Sorg C., Vogl T., Roth J., Gabrilovich D. I. (2008) Inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer is regulated by S100A9 protein. J. Exp. Med. 205, 2235–2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Serafini P., Carbley R., Noonan K. A., Tan G., Bronte V., Borrello I. (2004) High-dose granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 64, 6337–6343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kusmartsev S., Eruslanov E., Kübler H., Tseng T., Sakai Y., Su Z., Kaliberov S., Heiser A., Rosser C., Dahm P., Siemann D., Vieweg J. (2008) Oxidative stress regulates expression of VEGFR1 in myeloid cells. Link to tumor-induced immune suppression in renal cell carcinoma. J. Immunol. 181, 346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fricke I., Mirza N., Dupont J., Lockhart C., Jackson A., Lee J. H., Sosman J. A., Gabrilovich D. I. (2007) Vascular endothelial growth factor-trap overcomes defects in dendritic cell differentiation but does not improve antigen-specific immune responses. Clin Cancer Res. 13, 4840–4848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corzo C. A., Condamine T., Lu L., Cotter M. J., Youn J. I., Cheng P., Cho H. I., Celis E., Quiceno D. G., Padhya T., McCaffrey T. V., McCaffrey J. C., Gabrilovich D. I. (2010) HIF-1α regulates function and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2439–2453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Waight J. D., Hu Q., Miller A., Liu S., Abrams S. I. (2011) Tumor-derived G-CSF facilitates neoplastic growth through a granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell-dependent mechanism. PLoS ONE 6, e27690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mundy-Bosse B. L., Lesinski G. B., Jaime-Ramirez A. C., Benninger K., Khan M., Kuppusamy P., Guenterberg K., Kondadasula S. V., Chaudhury A. R., La Perle K. M., Kreiner M., Young G., Guttridge D. C., Carson W. E., 3rd (2011) Myeloid-derived suppressor cell inhibition of the IFN response in tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 71, 5101–5110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Turnquist H. R., Zhao Z., Rosborough B. R., Liu Q., Castellaneta A., Isse K., Wang Z., Lang M., Stolz D. B., Zheng X. X., Demetris A. J., Liew F. Y., Wood K. J., Thomson A. W. (2011) IL-33 expands suppressive CD11b+Gr-1(int) and regulatory T cells, including ST2L+ Foxp3+ cells, and mediates regulatory T cell-dependent promotion of cardiac allograft survival. J. Immunol. 187, 4598–4610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Obermajer N., Muthuswamy R., Lesnock J., Edwards R. P., Kalinski P. (2011) Positive feedback between PGE2 and COX2 redirects the differentiation of human dendritic cells toward stable myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood 118, 5498–5505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jayaraman P., Parikh F., Lopez-Rivera E., Hailemichael Y., Clark A., Ma G., Cannan D., Ramacher M., Kato M., Overwijk W. W., Chen S. H., Umansky V. Y., Sikora A. G. (2012) Tumor-expressed inducible nitric oxide synthase controls induction of functional myeloid-derived suppressor cells through modulation of vascular endothelial growth factor release. J. Immunol. 188, 5365–5376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lechner M. G., Liebertz D. J., Epstein A. L. (2010) Characterization of cytokine-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells from normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Immunol. 185, 2273–2284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qu P., Yan C., Blum J. S., Kapur R., Du H. (2011) Myeloid-specific expression of human lysosomal acid lipase corrects malformation and malfunction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in lal−/− mice. J. Immunol. 187, 3854–3866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He D., Li H., Yusuf N., Elmets C. A., Li J., Mountz J. D., Xu H. (2010) IL-17 promotes tumor development through the induction of tumor promoting microenvironments at tumor sites and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J. Immunol. 184, 2281–2288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sinha P., Chornoguz O., Clements V. K., Artemenko K. A., Zubarev R. A., Ostrand-Rosenberg S. (2011) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells express the death receptor Fas and apoptose in response to T cell-expressed FasL. Blood 117, 5381–5390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Straus S. E., Jaffe E. S., Puck J. M., Dale J. K., Elkon K. B., Rösen-Wolff A., Peters A. M., Sneller M. C., Hallahan C. W., Wang J., Fischer R. E., Jackson C. M., Lin A. Y., Bäumler C., Siegert E., Marx A., Vaishnaw A. K., Grodzicky T., Fleisher T. A., Lenardo M. J. (2001) The development of lymphomas in families with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome with germline Fas mutations and defective lymphocyte apoptosis. Blood 98, 194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu K. (2010) Role of apoptosis resistance in immune evasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2, 399–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu F., Liu Q., Yang D., Bollag W. B., Robertson K., Wu P., Liu K. (2011) Verticillin A overcomes apoptosis resistance in human colon carcinoma through DNA methylation-dependent up-regulation of BNIP3. Cancer Res. 71, 6807–6816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Burchert A., Cai D., Hofbauer L. C., Samuelsson M. K., Slater E. P., Duyster J., Ritter M., Hochhaus A., Müller R., Eilers M., Schmidt M., Neubauer A. (2004) Interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP; IRF-8) antagonizes BCR/ABL and down-regulates bcl-2. Blood 103, 3480–3489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang J., Hu X., Zimmerman M., Torres C. M., Yang D., Smith S. B., Liu K. (2011) Cutting edge. IRF8 regulates Bax transcription in vivo in primary myeloid cells. J. Immunol. 187, 4426–4430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hu X., Yang D., Zimmerman M., Liu F., Yang J., Kannan S., Burchert A., Szulc Z., Bielawska A., Ozato K., Bhalla K., Liu K. (2011) IRF8 regulates acid ceramidase expression to mediate apoptosis and suppresses myelogeneous leukemia. Cancer Res. 71, 2882–2891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang D., Torres C. M., Bardhan K., Zimmerman M., McGaha T. L., Liu K. (2012) Decitabine and vorinostat cooperate to sensitize colon carcinoma cells to fas ligand-induced apoptosis in vitro and tumor suppression in vivo. J. Immunol. 188, 4441–4449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gabriele L., Phung J., Fukumoto J., Segal D., Wang I. M., Giannakakou P., Giese N. A., Ozato K., Morse H. C. (1999) Regulation of apoptosis in myeloid cells by interferon consensus sequence-binding protein. J. Exp. Med. 190, 411–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang D., Thangaraju M., Browning D. D., Dong Z., Korchin B., Lev D. C., Ganapathy V., Liu K. (2007) IFN regulatory factor 8 mediates apoptosis in nonhemopoietic tumor cells via regulation of Fas expression. J. Immunol. 179, 4775–4782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Holtschke T., Löhler J., Kanno Y., Fehr T., Giese N., Rosenbauer F., Lou J., Knobeloch K. P., Gabriele L., Waring J. F., Bachmann M. F., Zinkernagel R. M., Morse H. C., 3rd, Ozato K., Horak I. (1996) Immunodeficiency and chronic myelogenous leukemia-like syndrome in mice with a targeted mutation of the ICSBP gene. Cell 87, 307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stewart T. J., Greeneltch K. M., Reid J. E., Liewehr D. J., Steinberg S. M., Liu K., Abrams S. I. (2009) Interferon regulatory factor-8 modulates the development of tumour-induced CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 13, 3939–3950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Meng X. W., Peterson K. L., Dai H., Schneider P., Lee S. H., Zhang J. S., Koenig A., Bronk S., Billadeau D. D., Gores G. J., Kaufmann S. H. (2011) High cell surface death receptor expression determines type I versus type II signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35823–35833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ikner A., Ashkenazi A. (2011) TWEAK induces apoptosis through a death-signaling complex comprising receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1), Fas-associated death domain (FADD), and caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 21546–21554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Toivonen H. T., Meinander A., Asaoka T., Westerlund M., Pettersson F., Mikhailov A., Eriksson J. E., Saxén H. (2011) Modeling reveals that dynamic regulation of c-FLIP levels determines cell-to-cell distribution of CD95-mediated apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 18375–18382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shoemaker A. R., Oleksijew A., Bauch J., Belli B. A., Borre T., Bruncko M., Deckwirth T., Frost D. J., Jarvis K., Joseph M. K., Marsh K., McClellan W., Nellans H., Ng S., Nimmer P., O'Connor J. M., Oltersdorf T., Qing W., Shen W., Stavropoulos J., Tahir S. K., Wang B., Warner R., Zhang H., Fesik S. W., Rosenberg S. H., Elmore S. W. (2006) A small-molecule inhibitor of Bcl-XL potentiates the activity of cytotoxic drugs in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 66, 8731–8739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ashkenazi A. (2002) Targeting death and decoy receptors of the tumour-necrosis factor superfamily. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 420–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ashkenazi A. (2008) Directing cancer cells to self-destruct with pro-apoptotic receptor agonists. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 1001–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lavrik I. N., Krammer P. H. (2012) Regulation of CD95/Fas signaling at the DISC. Cell Death Differ 19, 36–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nikolov N. P., Shimizu M., Cleland S., Bailey D., Aoki J., Strom T., Schwartzberg P. L., Candotti F., Siegel R. M. (2010) Systemic autoimmunity and defective Fas ligand secretion in the absence of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Blood 116, 740–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lenardo M. J., Oliveira J. B., Zheng L., Rao V. K. (2010) ALPS-ten lessons from an international workshop on a genetic disease of apoptosis. Immunity 32, 291–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. LeBlanc H., Lawrence D., Varfolomeev E., Totpal K., Morlan J., Schow P., Fong S., Schwall R., Sinicropi D., Ashkenazi A. (2002) Tumor-cell resistance to death receptor-induced apoptosis through mutational inactivation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 homolog Bax. Nat. Med. 8, 274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kim P. K., Mahidhara R., Seol D. W. (2001) The role of caspase-8 in resistance to cancer chemotherapy. Drug Resist. Updat 4, 293–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mohr A., Zwacka R. M., Jarmy G., Büneker C., Schrezenmeier H., Döhner K., Beltinger C., Wiesneth M., Debatin K. M., Stahnke K. (2005) Caspase-8L expression protects CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and leukemic cells from CD95-mediated apoptosis. Oncogene 24, 2421–2429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Scaffidi C., Medema J. P., Krammer P. H., Peter M. E. (1997) FLICE is predominantly expressed as two functionally active isoforms, caspase-8/a and caspase-8/b. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 26953–26958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lavrik I. N., Mock T., Golks A., Hoffmann J. C., Baumann S., Krammer P. H. (2008) CD95 stimulation results in the formation of a novel death effector domain protein-containing complex. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26401–26408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kober A. M., Legewie S., Pforr C., Fricker N., Eils R., Krammer P. H., Lavrik I. N. (2011) Caspase-8 activity has an essential role in CD95/Fas-mediated MAPK activation. Cell Death Dis. 2, e212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sharp D. A., Lawrence D. A., Ashkenazi A. (2005) Selective knockdown of the long variant of cellular FLICE inhibitory protein augments death receptor-mediated caspase-8 activation and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19401–19409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yang D., Wang S., Brooks C., Dong Z., Schoenlein P. V., Kumar V., Ouyang X., Xiong H., Lahat G., Hayes-Jordan A., Lazar A., Pollock R., Lev D., Liu K. (2009) IFN regulatory factor 8 sensitizes soft tissue sarcoma cells to death receptor-initiated apoptosis via repression of FLICE-like protein expression. Cancer Res. 69, 1080–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yamamoto M., Kato T., Hotta C., Nishiyama A., Kurotaki D., Yoshinari M., Takami M., Ichino M., Nakazawa M., Matsuyama T., Kamijo R., Kitagawa S., Ozato K., Tamura T. (2011) Shared and distinct functions of the transcription factors IRF4 and IRF8 in myeloid cell development. PLoS ONE 6, e25812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Stewart T. J., Liewehr D. J., Steinberg S. M., Greeneltch K. M., Abrams S. I. (2009) Modulating the expression of IFN regulatory factor 8 alters the protumorigenic behavior of CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells. J. Immunol. 183, 117–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mempel T. R., Pittet M. J., Khazaie K., Weninger W., Weissleder R., von Boehmer H., von Andrian U. H. (2006) Regulatory T cells reversibly suppress cytotoxic T cell function independent of effector differentiation. Immunity 25, 129–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chen M. L., Pittet M. J., Gorelik L., Flavell R. A., Weissleder R., von Boehmer H., Khazaie K. (2005) Regulatory T cells suppress tumor-specific CD8 T cell cytotoxicity through TGF-β signals in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 419–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kilinc M. O., Rowswell-Turner R. B., Gu T., Virtuoso L. P., Egilmez N. K. (2009) Activated CD8+ T-effector/memory cells eliminate CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T-suppressor cells from tumors via FasL-mediated apoptosis. J. Immunol. 183, 7656–7660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Suzuki E., Kapoor V., Jassar A. S., Kaiser L. R., Albelda S. M. (2005) Gemcitabine selectively eliminates splenic Gr-1+/CD11b+ myeloid suppressor cells in tumor-bearing animals and enhances antitumor immune activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 6713–6721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kusmartsev S., Cheng F., Yu B., Nefedova Y., Sotomayor E., Lush R., Gabrilovich D. (2003) All-trans-retinoic acid eliminates immature myeloid cells from tumor-bearing mice and improves the effect of vaccination. Cancer Res. 63, 4441–4449 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Melani C., Sangaletti S., Barazzetta F. M., Werb Z., Colombo M. P. (2007) Amino-biphosphonate-mediated MMP-9 inhibition breaks the tumor-bone marrow axis responsible for myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and macrophage infiltration in tumor stroma. Cancer Res. 67, 11438–11446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Serafini P., Meckel K., Kelso M., Noonan K., Califano J., Koch W., Dolcetti L., Bronte V., Borrello I. (2006) Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition augments endogenous antitumor immunity by reducing myeloid-derived suppressor cell function. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2691–2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ozao-Choy J., Ma G., Kao J., Wang G. X., Meseck M., Sung M., Schwartz M., Divino C. M., Pan P. Y., Chen S. H. (2009) The novel role of tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the reversal of immune suppression and modulation of tumor microenvironment for immune-based cancer therapies. Cancer Res. 69, 2514–2522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yang L., Huang J., Ren X., Gorska A. E., Chytil A., Aakre M., Carbone D. P., Matrisian L. M., Richmond A., Lin P. C., Moses H. L. (2008) Abrogation of TGF β signaling in mammary carcinomas recruits Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells that promote metastasis. Cancer Cell 13, 23–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rooswinkel R. W., van de Kooij B., Verheij M., Borst J. (2012) Bcl-2 is a better ABT-737 target than Bcl-xL or Bcl-w, and only Noxa overcomes resistance mediated by Mcl-1, Bfl-1, or Bcl-B. Cell Death Dis. 3, e366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Koenigsmann J., Carstanjen D. (2009) Loss of Irf8 does not co-operate with overexpression of BCL-2 in the induction of leukemias in vivo. Leuk. Lymphoma 50, 2078–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.