Abstract

The spatial and temporal control of Filamenting temperature sensitive mutant Z (FtsZ) Z-ring formation is crucial for proper cell division in bacteria. In Escherichia coli, the synthetic lethal with a defective Min system (SlmA) protein helps mediate nucleoid occlusion, which prevents chromosome fragmentation by binding FtsZ and inhibiting Z-ring formation over the nucleoid. However, to perform its function, SlmA must be bound to the nucleoid. To deduce the basis for this chromosomal requirement, we performed biochemical, cellular, and structural studies. Strikingly, structures show that SlmA dramatically distorts DNA, allowing it to bind as an orientated dimer-of-dimers. Biochemical data indicate that SlmA dimer-of-dimers can spread along the DNA. Combined structural and biochemical data suggest that this DNA-activated SlmA oligomerization would prevent FtsZ protofilament propagation and bundling. Bioinformatic analyses localize SlmA DNA sites near membrane-tethered chromosomal regions, and cellular studies show that SlmA inhibits FtsZ reservoirs from forming membrane-tethered Z rings. Thus, our combined data indicate that SlmA DNA helps block Z-ring formation over chromosomal DNA by forming higher-order protein-nucleic acid complexes that disable FtsZ filaments from coalescing into proper structures needed for Z-ring creation.

Accurate cell division demands a tight synchronization of chromosome replication, segregation, and septum formation. In bacteria, cell division is mediated by the tubulin-like protein, FtsZ (1–5). FtsZ self-assembles into linear protofilaments (pfs) in a GTP-dependent manner by the interaction of the plus end of one subunit with the minus end of another subunit. These pfs combine to form a septal ring-like structure called the Z ring, which drives cell division (1). The precise organization of FtsZ filaments in the Z ring has not been resolved. However, recent cryo-electron microscopy (EM) tomography and superresolution imaging data suggest that lateral contacts between FtsZ molecules in the Z ring are loosely arranged (6–9). Notably, the intracellular levels of FtsZ remain unchanged during the cell cycle and exceed the critical concentration required for Z-ring formation (3). Hence, Z-ring assembly is affected by a diverse repertoire of FtsZ binding proteins that ensure that the ring forms at the correct time and place during cell division (2, 4, 10). Two key regulatory systems, the Min and nucleoid occlusion (NO) systems, ensure that Z rings do not form at cell poles and over chromosomal DNA (11–13). In Escherichia coli, the Min system creates a gradient of FtsZ polymer inhibition at the cell poles (14). In contrast to the pole proximal effect of the Min system, NO prevents Z rings from forming over chromosomal DNA (15).

Although the effects of NO are well known, only in recent years have effectors of this process been identified in both gram-negative and gram-positive model organisms. Surprisingly, the gram-positive model organism, Bacillus subtilis, uses a ParB-like protein called Noc, whereas in E. coli the TetR-family member, SlmA, has been shown to be involved in NO (13, 16–18). Recent studies showed that SlmA binds directly to FtsZ and that this interaction antagonizes Z-ring formation when SlmA is bound to specific DNA sites (16, 17). These DNA sequences, called SlmA binding sites (SBSs), are evenly distributed on the chromosome, with the notable exception of the Ter chromosomal region, which is the last to partition. Similar to SlmA, the unrelated Noc protein also binds specific DNA sites that are distributed in all chromosomal regions but the Ter containing domain (18, 19). Thus, NO factors coordinate DNA segregation and cell division.

How SlmA prevents Z-ring formation by FtsZ is unclear. However, a key finding was that this inhibition necessitates that SlmA be bound to its specific DNA sites (16, 17). In fact, SlmA alone does not affect FtsZ filament formation, making SlmA the only known FtsZ assembly/disassembly factor that requires DNA for its function. To determine the molecular basis for the specific chromosomal DNA requirement for SlmA’s NO function, we performed structural, bioinformatic, cellular, and biochemical studies. Strikingly, these data show that SlmA interacts with specific SBS sites to form a higher-order structure that can spread on the DNA. Combined with biochemical and bioinformatics analyses, these findings suggest a molecular model for how SlmA participates in NO in gram-negative bacteria.

Results and Discussion

SlmA-SBS Does Not Alter FtsZ GTPase Activity or Block Assembly of FtsZ Protofilaments.

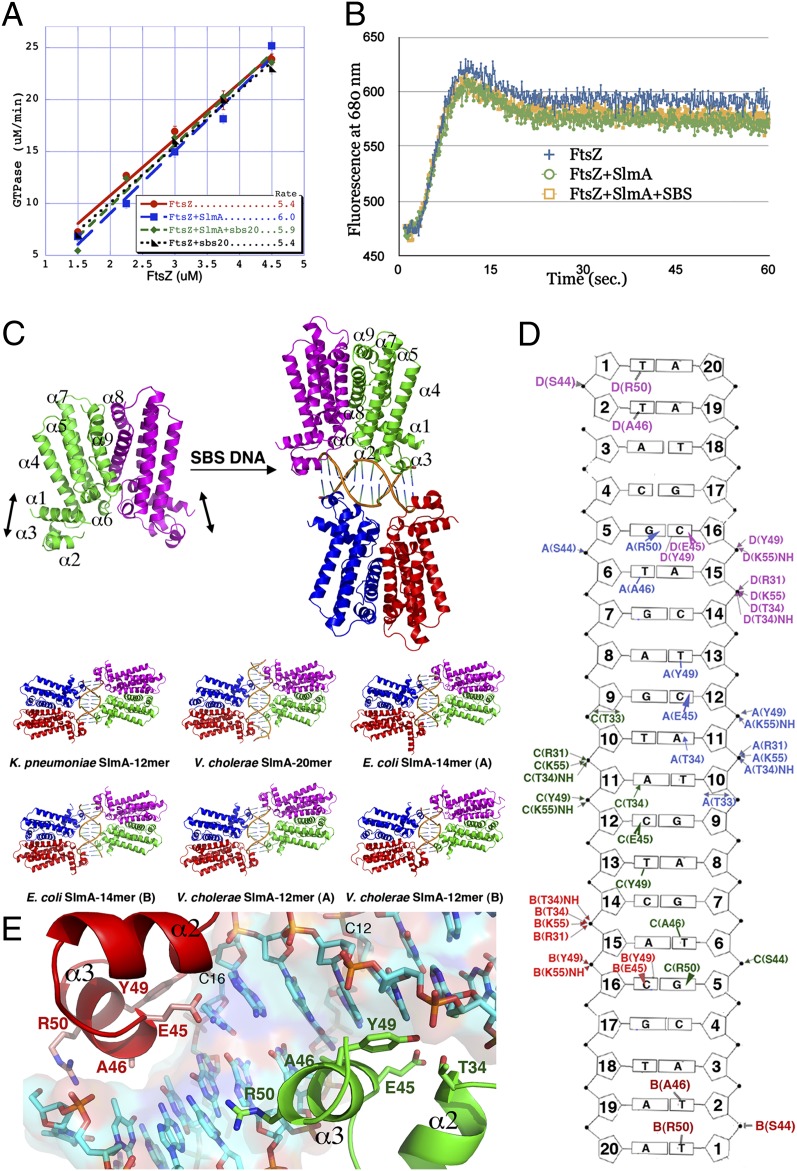

Previous studies showed that, whereas SlmA alone does not affect FtsZ filament formation or assembly, SlmA-SBS complexes block higher-order FtsZ polymerization (16, 17). These data could be explained by impacts on FtsZ GTPase activity, pfs formation, or filament assembly into the Z ring or a combination of these effects. To test the effects of E. coli SlmA and SlmA-SBS on FtsZ GTPase activity, we used a continuous, regenerative coupled assay, as previously described (20). These experiments showed that the rate of GTP hydrolysis by FtsZ ± SBS DNA was 5.4 (GTP molecules hydrolyzed per FtsZ per minute), whereas it was 5.9 and 6.0 in the presence of SlmA-SBS and SlmA, respectively (20) (Fig. 1A). Previous studies suggested that SlmA increases FtsZ GTPase activity by 36% compared with the 10% we observed (17). These differences likely reflect distinct experimental conditions; our experiments were done in 100 mM KAc, 5 mM MgAc, and 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.7, compared with 200 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM Pipes, pH 6.7, used by the previous study (17). Increases of 10%–36% are within the errors of the experiments, suggesting that if there is an SlmA-SBS effect on FtsZ GTPase activity, it is likely small (21, 22).

Fig. 1.

Effect of SlmA-SBS on FtsZ GTP hydrolysis and protofilament formation and SlmA-SBS structures. (A) GTP turnover by FtsZ measured in the presence and absence of an equimolar concentration of SBS DNA, SlmA, or SlmA-SBS. In all cases, the concentration of SlmA is that of the monomeric subunits. The slope of the line above the 1.0 µM critical concentration is given in the inset. (B) FtsZ filament formation as measured by an ATTO fluorescence assay, where the increase in ATTO fluorescence measures pfs assembly. (C) Structures of SlmA apo and SlmA-SBS complexes. Arrows indicate dynamic nature of DNA binding regions of apo SlmA. C, E, and Fig. 2 A–C were made using PyMOL (34). Ribbon diagrams showing independent SlmA-SBS structures that were solved. Note that all bind as dimer-of-dimers and kink the DNA. (D) Schematic representation of the SlmA-DNA contacts. Residues that interact via hydrogen bond (arrow) or hydrophobic contact (line) are colored according to the subunit. (E) Close up of the base specific contacts made to each half site by two SlmA subunits (from different dimers).

Previous sedimentation experiments indicated that SlmA-SBS reduced polymer formation by FtsZ (17). However, such assays only provide a readout of the production or reduction of large FtsZ filaments or bundles and hence do not evaluate pfs formation. Thus, we used an ATTO-based fluorescence assay, using FtsZ(T151C-ATTO/Y222W), which can detect FtsZ-FtsZ interactions involved in the formation of single FtsZ pfs (20). This FtsZ mutant is also optimal for these particular experiments as our previous FtsZ-SlmA small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) model predicts that FtsZ residues 151 and 222 would be far, >20 Å, from SlmA in the complex (Fig. S1 A and B). Previous studies established that in the monomer form of FtsZ (minus GTP), the ATTO fluorescence is strongly quenched by the nearby tryptophan. On assembly, a small conformational change in the subunit moves the ATTO away from the tryptophan, resulting in its reduced quenching and an increase in fluorescence (20). When ATTO-labeled FtsZ is used as a dilute (1/10) label, pfs assembly is dominated by WT FtsZ. As for the GTPase assays, these studies were performed using SlmA protein concentrations above the apparent dissociations constants for FtsZ, and these experiments were initiated by the addition of 2 mM GTP (16). The ATTO fluorescence profiles of FtsZ (3 μM), FtsZ-SlmA (3 μM FtsZ and 3 μM SlmA), and FtsZ-SlmA-SBS (3 μM FtsZ, 3 μM SlmA, and 6 μM SBS) in the presence of 2 mM GTP are shown in Fig. 1B. As previously observed, FtsZ filament formation on GTP addition is accompanied by a large increase in fluorescence (20). The FtsZ-SlmA and FtsZ-SlmA-DNA samples gave essentially identical kinetics and levels of assembly, which suggests that neither SlmA nor SlmA-SBS inhibits the formation of FtsZ pfs. However, to more directly assess if FtsZ can still form single pfs in the presence of SlmA and SlmA-SBS, we carried out negative stain EM studies. Such EM analyses must be interpreted with caution as previous studies have revealed that FtsZ can form dramatically different types of polymers and other structures, which are dependent on the method used, the buffer, and pH (22). Likewise, using different buffers and pH, we found that FtsZ can form distinct structures in the presence of SlmA-SBS by EM. Thus, we used a method shown to produce fewer polymer artifacts (3, 23) (SI Materials and Methods). This approach uses EM grids covered in a thin carbon film made hydrophilic by UV light and its accompanying exposure to ozone (23). We used this technique to address (i) if the presence of SlmA or SlmA-SBS prevents single pfs formation and (ii) if the presence of SlmA or SlmA-SBS leads to FtsZ bundling. As can be seen in Fig. S2 A–D, neither SlmA nor SlmA-SBS prevented the formation of single FtsZ pfs formation, and bundles were observed rarely in SlmA, SlmA-SBS, and minus SlmA samples. Hence, our combined data indicate that SlmA-SBS does not function in NO by preventing the formation of single protofilaments.

Crystal Structures of SlmA and SlmA-SBS Complexes.

Our data demonstrate that SlmA-SBS does not significantly affect the GTPase activity of FtsZ or its ability to form pfs. Thus, these data indicate that SlmA-DNA must function by inhibiting higher-order structural formation of FtsZ pfs. SAXS studies also showed that FtsZ interacts with the C-terminal dimer domain of SlmA (16). These data suggest that DNA binding by SlmA might alter the conformation of the SlmA C-terminal dimer domain, either by causing a rotation of one subunit relative to the other or initiating significant tertiary structural changes in each dimer domain, which would affect FtsZ filament structure. Alternatively, DNA binding might itself alter SlmA oligomerization that would then impinge on FtsZ polymerization. To deduce the mechanism involved, we performed crystallographic studies on the unliganded or apo SlmA and SlmA-SBS complexes. Bioinformatic analyses show that SlmA proteins are highly conserved in gram-negative bacteria. To increase our chances of obtaining well-diffracting crystals for apo and SBS-bound forms, we performed structural studies on E. coli SlmA, as well as the Vibrio cholerae and Klebsiella pneumoniae proteins, which share 67% and 95% sequence identity, respectively, with E. coli SlmA. Importantly, our bioinformatic analyses also showed that the V. cholerae and K. pneumoniae SBS sites are dispersed over the chromosomes with the exception of the Ter region, similar to what is observed in E. coli (Fig. S3). Furthermore, fluorescence polarization (FP) DNA-binding studies demonstrated that K. pneumoniae and V. cholerae SlmA bind the same SBS site as E. coli SlmA with comparable Kds (range, 109–162 nM; Fig. S4A).

Three apo SlmA structures were solved: one of V. cholerae SlmA and two of K. pneumoniae SlmA (SI Materials and Methods; Tables S1A and S1B). Notably, these SlmA structures were obtained with his-tag free proteins. It was previously demonstrated that the his-tag does not affect SlmA dimerization (16), and all TetR proteins studied thus far function as dimers (24–26). We also showed that the his-tag does not affect DNA (Fig. S5) or FtsZ binding (Fig. S4B; SI Materials and Methods). As observed previously for E. coli SlmA, these apo structures contain a TetR fold with two domains: an N-terminal HTH domain and C-terminal dimer domain (16) (Fig. S6A). Cα overlays of the apo structures reveal that the dimer domains adopt the same conformation; however, the DNA binding domains and region connecting the DNA binding and dimer domains show flexibility. This finding is not surprising as TetR proteins all display plasticity within these regions when not bound to DNA (24–26). Data suggest that this flexibility is important in allowing optimal adjustment during DNA docking (24–26). The marked flexibility in the DNA binding domains of the apo SlmA structures is underscored by the fact that in two of the three apo structures, residues 26–32 are completely disordered, and poor electron density is observed for α1.

To gain insight into the molecular basis for the SBS requirement of SlmA’s NO function, we next determined structures of six SlmA-SBS complexes; four V. cholerae, one E. coli, and one K. pneumoniae SlmA-SBS complex were obtained. Again, his-tag free proteins were used (SI Materials and Methods; Tables S1A and S1B). The results were very surprising. In all cases, SlmA binds its SBS site as dimer-of-dimers, despite the fact that the initial crystallization conditions used a SlmA dimer:DNA duplex ratio of 1:1 (Fig. 1C). Notably, better crystals were subsequently obtained when using a SlmA dimer:DNA duplex of 2:1. The finding that all structures, which were obtained under different conditions with SlmA proteins from different gram-negative bacteria, show the same dimer-of-dimer binding indicates that this is the specific DNA binding mode used by enterobacterial SlmA proteins (Fig. 1 D and E). DNA binding locks in a specific conformation; all of the DNA bound forms of SlmA adopt identical conformations, not only in their dimerization domain but also in DNA binding domains. Comparisons of the apo vs. SBS-bound SlmA structures again underscore the flexibility of the DNA binding domains in the apo state (Fig. S6B). In addition to the dynamic nature of the apo DNA binding domains, the region between the DNA binding and dimer domains (residues 103–125) also displays various degrees of flexibility in the apo compared with the DNA-bound forms, in particular residues 111–118 (Fig. S6B). This flexibility likely affords further plasticity for DNA docking (Fig. S6B). FtsZ binds to C-terminal regions of SlmA that are close to the DNA binding domains (16). Thus, it may be possible that the conformational locking of SlmA in one conformation by DNA binding could have some impact on FtsZ binding. However, the central and unexpected finding from the SlmA-SBS structures is that SlmA binds the DNA as dimer-of-dimers. This binding mode has important implications on its interaction with FtsZ and hence its NO mechanism, as discussed below.

SlmA-SBS Structures Reveal Specific Mode of Binding by SlmA Dimer-of-Dimers.

Examination of SlmA-SBS structures reveal conserved base-specific interactions important for DNA discrimination. A key contact that imparts specificity is a hydrogen bond from Glu45 to the N4 exocyclic atoms of cytosines 12 and 16 on both DNA strands (Fig. 1 D and E). Interestingly, there is a pseudo-direct repeat within each half site such that each of the four repeats contains two CG base pairs that are each contacted by the side chain of Glu45. Thus, Glu45 makes four base-specific interactions per SBS site. These C-G bps are flanked on their 3′ ends by A-T or T-A bps, which are specified by hydrophobic residues. The side chains of Ala46 contact thymine 6, whereas Tyr49 interacts with both thymine 13 and cytosine 16. These combined contacts provide six additional base-specifying interactions. Finally, the side chain of Arg50 from one subunit interacts with guanine 1 on each strand (Fig. 1 D and E). SlmA residues that interact with bases are completely conserved in all SlmA proteins. Moreover, the nucleotides they interact with correspond to those identified in our DNA selection experiments (GTgAGtaCTcAC) (where capital letters denote key nucleotides for DNA specific binding by SlmA) to be key for SlmA binding (16). The SlmA-20mer complex showed two additional base interactions and one phosphate contact on each DNA end. Consistent with this, FP analyses showed that the SlmA proteins bound a 20mer SBS DNA with a slight (twofold) enhancement compared with the 12mer site (Fig. S4A).

Formation of Oriented SlmA Dimer-of-Dimers Requires Dramatic DNA Distortions.

TetR proteins display a range of DNA binding modes, yet these interactions typically do not cause dramatic DNA deformations (24–26). By contrast, the binding of SlmA to the SBS leads to significant DNA distortions. Most notable are two symmetric kinks located at bps 9/10 on each side of the SBS (Fig. 2 A–C). These kinks result in a large opening of the minor groove, to 10 Å (compared with 5.7 Å for B-DNA). Remarkably, the identical twofold related kinks are observed in all SlmA-SBS structures (Figs. 1C and 2B). These kinks are created by the close interaction of the centrally located HTH motif from one subunit of each dimer with the DNA (Fig. 2A). This close approach permits optimal base and phosphate contacts. However, it also places the side chain of Thr33, located on the first helix of the HTH, within overlapping van der Waals contact of the phosphate backbone. Hence, the Thr33 side chain intercalates into the phosphate backbone, causing it to pop out of alignment (Fig. 2C). This distortion not only anchors the dimer onto the DNA but also deforms the DNA near the binding site of the second dimer, likely resulting in cooperative binding (see below). The ejected phosphate group is stabilized by Arg31, which stacks behind it. Previous studies revealed that a SlmA(T33A) missense mutation is defective in NO and in SBS binding (17). Indeed, Thr33 is absolutely conserved in all SlmA proteins. The fact that Thr33 does not participate in base or hydrogen bonding interactions provides strong support for the supposition that Thr33 mediated DNA deformation is essential for SlmA binding to the SBS.

Fig. 2.

SlmA binding causes dramatic DNA distortion. (A) Ribbon diagram showing the SlmA-bound SBS DNA highlighting the dramatic twofold related kinks in the central steps of the DNA. (B) Overlays of the SlmA-bound SBS sites from all SlmA-SBS crystal structures demonstrating that every DNA site has the identical twofold related central DNA kinks. (C) Close up of the Thr33 interaction with the popped out phosphate group that gives rise to the dramatic DNA distortion.

The overall properties of the SlmA-bound DNA, which has an overall bend angle of 18°, are also atypical and display some A-DNA–like characteristics. For example, the average helical twist and rise per residue of SlmA-bound SBS DNA sites are 32.5° and 3.3 Å, respectively (helical twists and rise per residues for A-DNA and B-DNA are 33°/3.3 Å and 36°/2.8 Å, respectively). Unlike the dramatic kinking in the central minor groove, which is localized, the major grooves at each end of the site are gradually widened (average major groove widths are 12.9 Å compared with 11.7 Å for B-DNA and 2.7 Å for A-DNA), allowing docking of two subunits into each major groove. Again, these characteristic DNA distortions are found in all SlmA-DNA structures.

Isothermal titration calorimetry and FP studies demonstrate that SlmA binds SBS as dimer-of-dimers in solution.

All our SlmA-SBS structures reveal a dimer-of-dimer binding mode. However, to assess SlmA-SBS binding in solution, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and FP. ITC isotherms revealed that SlmA binds the SBS with a Kd of 87 ± 26 nM and a stoichiometry of two SlmA dimers to one duplex DNA (Fig. 3A). FP also indicated that two SlmA dimers bind a single SBS duplex (Fig. 3B). Thus, both ITC and FP studies confirmed that SlmA binds the SBS as a dimer-of-dimer. Moreover, the combined data indicate that the SlmA-SBS dimer-of-dimer interaction is cooperative, as intermediate steps were not observed in ITC or FP studies, and only dimer-of-dimer SlmA-SBS structures were obtained. Moreover, SlmA cannot bind stably to DNA containing just one half SBS site (Fig. S7A). Because there are no contacts between SlmA dimers, the cooperativity must be mediated by the structural changes induced in the DNA on binding the first dimer, which enhances the ability of the subsequent dimer to bind.

Fig. 3.

Determination of SlmA-SBS binding stoichiometry and spreading by SlmA. (A) Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) binding isotherm of SlmA binding to a 20-mer SBS DNA. The binding isotherm revealed the Kd to be ∼87 nM with a 4:1 (SlmA subunit:DNA duplex) stoichiometry. (B) FP binding curve performed at SBS DNA concentration >10-fold above the Kd. The inflection point denotes the point at which the DNA is specifically saturated with SlmA, indicating that 2 SlmA dimer binds to a 1 SBS duplex. (C) ITC binding isotherm of SlmA binding to a 40-mer SBS DNA (SBS40) revealed the stoichiometry to be 7.4:1 (SlmA:DNA), suggesting that four SlmA dimers are bound. The diagram above the isotherms is simply used to show the lengths and relative positions of binding sites and is not meant to indicate molecular contacts or lack thereof between SlmA molecules. (D) Through fine sampling of the initial SlmA-SBS40 binding event, a four-site binding model can be fitted. These data indicate that once SlmA binds the SBS as a dimer-of-dimer, it can spread to adjacent DNA. (E) SlmA-SBS-FtsZ SAXS structure. The SAXS envelope accommodates two SlmA dimers bound to a single SBS site and sandwiched by four FtsZ subunits. Shown as magenta cpk are residues that genetic studies suggest are involved in FtsZ interaction (30). (F) Modeling of FtsZ propagation when bound to SlmA-SBS. SlmA binds the SBS as a dimer-of-dimers and nucleates the binding of adjacent dimer-of-dimers, leading to spreading. Modeling shows that propagated FtsZ filaments that are bound to SlmA that is bound as oligomerized dimer-of-dimers clash, and the fixed orientation of FtsZ protofilaments held far apart by SlmA binding also likely impacts FtsZ bundling.

Interestingly, SBS sites are often clustered close together on the nucleoid, and SlmA is visualized as broadened regions on the DNA rather than discrete points (13). Moreover, more detailed ChIP analyses by Cho et al. showed that SlmA enriched regions extended adjacent to the SBS (17). The finding that SlmA binds DNA as a dimer-of-dimers helps explain these data. It has been estimated that there are ∼300–400 SlmA molecules per cell (13). Hence, given that SlmA binds as a dimer-of-dimer, the majority of the SlmA would be bound to SBS or SBS-like sites. The remaining SlmA molecules might be nucleated onto nearby DNA by the SBS-bound SlmA, which could further enhance its inhibitory action on FtsZ polymerization along the nucleoid. To test this possibility, we designed a 40-mer SBS DNA (SBS40) that contains only one SBS site and is flanked by an additional 20 bp of non-SBS DNA. Using ITC, we observed that 7.4 SlmA monomers bind SBS40, consistent with 4 SlmA dimers binding to SBS40 (Fig. 3C). This additional binding is not due to nonspecific DNA interaction, as SlmA cannot bind DNA that does not contain an embedded SBS (Fig. S7 B–D). To dissect the thermodynamic basis of this SlmA-DNA spreading interaction, we carried out ITC (Fig. 3D). Only a four-site binding model could adequately fit the resulting ITC data. The first two sites represent SlmA binding to the SBS and have Kds of 23.6 and 31.6 nM, similar to those previously determined. Altogether, these data suggest that SlmA binds to SBS sites as a dimer-of-dimers and that DNA distortion likely allows additional SlmA dimer-of-dimers to bind adjacent sites to mediate spreading. Strikingly, this DNA spreading function likely significantly enhances SlmA-mediated Z-ring disruption.

Combined SAXS and crystal structures suggest basis for SlmA-SBS–mediated disruption of FtsZ bundling.

Superimpositions of apo SlmA onto the SBS-bound form revealed structural differences in the regions between the DNA binding and C-terminal domains that, like other TetR proteins, are likely involved in DNA optimization for docking. However, the finding that SlmA binds DNA as a dimer-of-dimers, which can spread on the DNA, suggests that oligomerization is the key to SlmA’s NO function. To gain insight into how the higher-order oligomerization of SlmA onto the DNA might affect the polymerization functions of FtsZ, we performed SAXS studies on SlmA-SBS-FtsZ. Although SAXS cannot impart detailed atomic level information, it can provide insight into molecular arrangements. Consistent molecular envelopes were obtained of E. coli SlmA-SBS-FtsZ complexes (Fig. S8 A–F) (27–29). The SlmA-SBS structure could only be successfully docked into the center of the SAXS envelope, leaving four regions of unoccupied density flanking the SlmA proteins. Four FtsZ molecules could be fit into this extra density (Fig. 3E). The density for two of four FtsZ molecules is not completely observed. This reduced density is explained by the fact that a slight excess of SlmA to FtsZ had to be used to achieve homogeneous samples, as even an extremely small FtsZ surplus resulted in sample heterogeneity due to the formation of small pfs, preventing data analysis.

The SlmA-SBS-FtsZ SAXS model is consistent with our previous SlmA-FtsZ data, which showed that SlmA dimers are sandwiched by FtsZ (16). The study is also in line with our findings that SlmA-SBS binding has no significant impact on FtsZ pfs formation, as FtsZ pfs can be propagated when bound to SlmA DNA. However, the continued growth of these FtsZ pfs ultimately leads to pfs clash. In addition, FtsZ lateral contacts would be affected or even prevented in these complexes (Fig. 3F). Importantly, the interactions between SlmA and these propagated FtsZ filaments overlaps with residues suggested by recent genetic studies to be involved in the SlmA-FtsZ interaction, including Phe65, Arg73, Leu94, Gly97, Arg101, and Asn102 (Fig. 3F) (30).

Microscopy Studies Reveal SlmA-DNA Impacts FtsZ Reservoir Conversion to Z Rings.

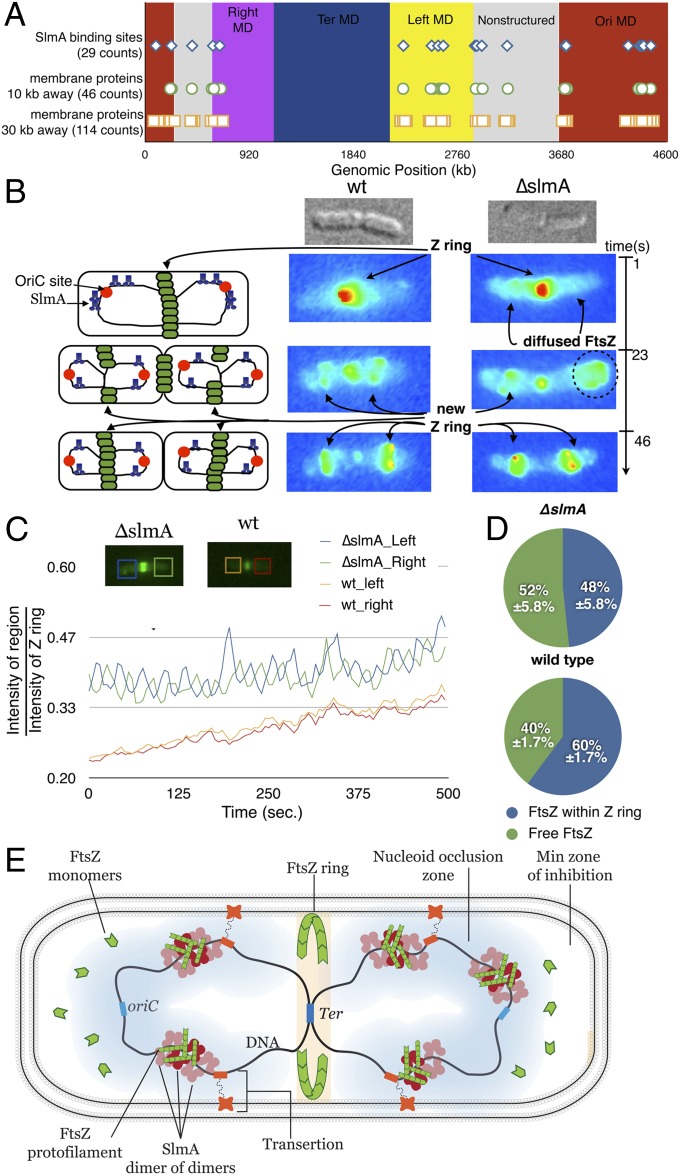

For SlmA-SBS binding to inhibit Z-ring formation, SlmA-DNA must be localized near FtsZ reservoirs. An FtsZ-GFP fusion protein displays dynamic movement with a periodicity resembling that of MinC oscillation. FtsZ not engaged in Z-ring formation has been found in cellular reservoirs that form helical-like structures, which appear to localize near the membrane (31). Indeed, sufficient pools of FtsZ must exist near the site of Z-ring formation, which is at the membrane near midcell. Recent data indicate that membrane protein expression in E. coli results in a dramatic shift of their genetic loci toward the membrane. This chromosome positioning on membrane protein expression is rapid and affects DNA regions >90 kb from the gene encoding the membrane protein (32). Therefore, we examined whether the SBS sites on the E. coli chromosomes bound by SlmA might be near membrane-encoding regions of the chromosome as such membrane localization could position SlmA-SBS near FtsZ reservoirs. Bioinformatic analyses showed that the frequency of membrane protein encoding genes is fairly evenly distributed throughout the E. coli genome. However, a large number of membrane encoding genes are within 10–30 kb of SBS sites and annotated as gene products involved in cell division, peptidoglycan/lipid biosynthesis, and transmembrane transport (Fig. 4A). Given that these processes are integral for cell division, these genes are likely to be transcriptionally and translationally active, and hence, these transertion (coupled transcription and insertion of nascent membrane protein) events can concomitantly localize these loci and SlmA binding sites toward the inner membrane.

Fig. 4.

Membrane localization of SlmA-DNA complexes impedes Z-ring formation near nucleoid DNA: model for SlmA-mediated NO. (A) Bioinformatic analysis mapping the E. coli chromosomal location of SBS sites and membrane encoded proteins, which act to tether the nucleoid near the membrane. (B) Fluorescence microscopy study comparing the FtsZ-GFP signal in WT and ΔslmA cells. In the ΔslmA cell, the FtsZ signal is more diffuse. (C) Plot of normalized FtsZ-GFP intensity in the left and right portion of cells before cytokinesis. Oscillation displayed by these curves represents the movement of FtsZ in the cell. In ΔslmA cells, amplitudes are strikingly higher than WT cells, indicating that FtsZ is not as organized and localized. (D) Comparisons of the amount of free FtsZ vs. FtsZ within the Z ring are shown for WT and ΔslmA cells. Amount of free FtsZ is consistently higher in ΔslmA cells. (E) Molecular model for SlmA-mediated NO. Shown is a segregating cell just starting division. The Z ring has begun formation at the cell center concomitant with segregation of the two chromosomes (black lines). SlmA dimer-of-dimers bind and spread on non-Ter regions, localized near the membrane by nearby genes, of the chromosome, thus preventing Z-ring formation by sequestration of pfs and inhibition of their growth. The absence of SlmA-SBS near the Ter macrodomain (MD) allows Z-ring formation near the cell center.

To test the hypothesis that SlmA binding to chromosomal DNA impacts conversion of FtsZ reservoirs to Z rings, we performed in vivo fluorescence microscopy studies. For these studies we used E. coli WM2724 and WM3156, which contain native ftsZ plus a lac promoter driving the expression of ftsZ-gfp at an ectopic chromosomal locus. The only difference between these strains is that WM3156 is ΔslmA. As anticipated, both strains exhibited normal cell division on IPTG induction (31). However, in the ΔslmA cells, the FtsZ-GFP was more diffuse (Movies S1, S2, S3, and S4). Fig. 4B compares one dividing cell from each strain visualized under identical growth and imaging conditions. These observations suggest that the amount of FtsZ outside the Z ring and oscillating freely from pole to pole is greater in cells lacking SlmA. To test this further, we examined oscillating FtsZ before cytokinesis and measured the fluorescence intensity of the FtsZ signal on the left and right portion of the cell (using the Z ring as an internal standard) over time in WT and ΔslmA cells (Fig. 4C; Fig. S9). Interestingly, FtsZ-GFP oscillation in ΔslmA cells displayed higher amplitudes (greater than fivefold) compared with WT cells, further suggesting that the amount of FtsZ not localized to the Z ring is higher ΔslmA in cells. To quantify the difference in free FtsZ molecules vs. those contributing to the formation of the Z ring, we analyzed the intensity signal outside vs. inside the Z ring of 30 ΔslmA and 30 WT cells (Fig. 4D). Strikingly, 52% of FtsZ in ΔslmA cells is not sequestered to the Z ring, whereas in WT cells, 40% of FtsZ is free. These results suggest that chromosome-bound SlmA localizes FtsZ toward the nucleoid region where the Z ring will form. The interaction of SlmA-SBS with FtsZ, however, prevents it from forming Z rings in the direct vicinity of the DNA. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that overproduction of SlmA can recruit FtsZ to the nucleoid (13). Thus, whereas recent data indicate that SlmA alone does not perform all NO functions, these data reveal how SlmA provides a failsafe mechanism to ensure that nucleoid DNA is not bisected during cell division (13, 33).

In conclusion, SlmA is notable as being the only FtsZ remodeling protein that requires DNA binding for its function. However, the basis for this DNA requirement has been unknown. Our data reveal the unexpected finding that SlmA forms dimer-of-dimers on DNA that spread along the DNA. These extended assemblies of SlmA dimers would be predicted to thwart the assembly of FtsZ pfs that are bound to SlmA-DNA clusters. Our data also reveal that SBS DNA binding by SlmA is accompanied by SBS-mediated ordering of the flexible DNA binding domains and regions connecting the DNA binding and dimer domain. This induced adjustment of the DNA binding domains might also play a role in the NO mechanism by affecting FtsZ filamentation, as extension of FtsZ pfs may come close to the DNA binding domains and hence be affected by their conformational locking. However, this effect would appear to be small relative to that mediated by SBS-induced SlmA higher-order oligomerization. Indeed, as noted, the main outcome of SlmA binding to the SBS is the formation of oriented SlmA dimer-of-dimers on the DNA, which then spread on the DNA. Modeling suggests that FtsZ filaments bound to DNA-oligomerized SlmA molecules would be randomly affixed and unable to extend to appropriate lengths and also unable to form lateral interactions (Fig. 3F). We posit that this chaotic arrangement of FtsZ molecules would hamper Z-ring formation. This model is also consistent with recent data showing that one functional FtsZ interaction side on a SlmA dimer is sufficient to mediate NO as the proximity of multiple SlmA dimers that bind even one FtsZ filament would prevent productive Z-ring formation over the nucleoid (30) (Fig. 4E). The sequestration of FtsZ by SlmA to the DNA is also an important aspect of its inhibitory mechanism. Thus, we propose that these combined factors, the forced arrangement of FtsZ pfs on “pockets” of SlmA bound on the chromosome and FtsZ sequestration, would prevent FtsZ from forming Z rings over the nucleoid.

Materials and Methods

Artificial genes (codon optimized for E. coli expression) encoding the SlmA proteins from V. cholerae and K. pneumoniae were obtained from Genscript Corporation and subcloned into pET15b for expression. Proteins were purified via nickel nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) chromatography, and the his-tags were removed. Biochemical and structural studies were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods. The X-ray intensity data for the crystals were collected at Advanced Light Source beamline 8.3.1 and processed with MOSFLM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Susanna S. Lai for help with Fig. 4E and Prof. Harold Erickson for helpful discussions and assistance with GTPase and ATTO assay interpretation. We thank the Advanced Light Source (ALS) and their support staff. The ALS is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. This work was supported by an MD Anderson Trust Fellowship and National Institutes of Health Grant GM074815 (to M.A.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 4GCK, 4GCL, 4GCT, 4GFL, and 4GFK).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1221036110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bi EF, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1991;354(6349):161–164. doi: 10.1038/354161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams DW, Errington J. Bacterial cell division: Assembly, maintenance and disassembly of the Z ring. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(9):642–653. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson HP, Anderson DE, Osawa M. FtsZ in bacterial cytokinesis: Cytoskeleton and force generator all in one. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74(4):504–528. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00021-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margolin W. FtsZ and the division of prokaryotic cells and organelles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(11):862–871. doi: 10.1038/nrm1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osawa M, Anderson DE, Erickson HP. Reconstitution of contractile FtsZ rings in liposomes. Science. 2008;320(5877):792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1154520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biteen JS, Goley ED, Shapiro L, Moerner WE. Three-dimensional super-resolution imaging of the midplane protein FtsZ in live Caulobacter crescentus cells using astigmatism. ChemPhysChem. 2012;13(4):1007–1012. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, Trimble MJ, Brun YV, Jensen GJ. The structure of FtsZ filaments in vivo suggests a force-generating role in cell division. EMBO J. 2007;26(22):4694–4708. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu G, et al. In vivo structure of the E. coli FtsZ-ring revealed by photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9):e12682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings PC, Cox GC, Monahan LG, Harry EJ. Super-resolution imaging of the bacterial cytokinetic protein FtsZ. Micron. 2010;42:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romberg L, Levin PA. Assembly dynamics of the bacterial cell division protein FTSZ: Poised at the edge of stability. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:125–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.012903.074300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raskin DM, de Boer PA. Rapid pole-to-pole oscillation of a protein required for directing division to the middle of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(9):4971–4976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lutkenhaus J. Assembly dynamics of the bacterial MinCDE system and spatial regulation of the Z ring. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:539–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernhardt TG, de Boer PAJ. SlmA, a nucleoid-associated, FtsZ binding protein required for blocking septal ring assembly over chromosomes in E. coli. Mol Cell. 2005;18(5):555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih Y-L, Le T, Rothfield L. Division site selection in Escherichia coli involves dynamic redistribution of Min proteins within coiled structures that extend between the two cell poles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(13):7865–7870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232225100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulder E, Woldringh CL. Actively replicating nucleoids influence positioning of division sites in Escherichia coli filaments forming cells lacking DNA. J Bacteriol. 1989;171(8):4303–4314. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4303-4314.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tonthat NK, et al. Molecular mechanism by which the nucleoid occlusion factor, SlmA, keeps cytokinesis in check. EMBO J. 2011;30(1):154–164. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho H, McManus HR, Dove SL, Bernhardt TG. Nucleoid occlusion factor SlmA is a DNA-activated FtsZ polymerization antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(9):3773–3778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018674108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu LJ, Errington J. Coordination of cell division and chromosome segregation by a nucleoid occlusion protein in Bacillus subtilis. Cell. 2004;117(7):915–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu LJ, et al. Noc protein binds to specific DNA sequences to coordinate cell division with chromosome segregation. EMBO J. 2009;28(13):1940–1952. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Erickson HP. Conformational changes of FtsZ reported by tryptophan mutants. Biochemistry. 2011;50(21):4675–4684. doi: 10.1021/bi200106d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Milam SL, Erickson HP. SulA inhibits assembly of FtsZ by a simple sequestration mechanism. Biochemistry. 2012;51(14):3100–3109. doi: 10.1021/bi201669d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popp D, Iwasa M, Narita A, Erickson HP, Maéda Y. FtsZ condensates: An in vitro electron microscopy study. Biopolymers. 2009;91(5):340–350. doi: 10.1002/bip.21136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgess SA, Walker ML, Thirumurugan K, Trinick J, Knight PJ. Use of negative stain and single-particle image processing to explore dynamic properties of flexible macromolecules. J Struct Biol. 2004;147(3):247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramos JL, et al. The TetR family of transcriptional repressors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69(2):326–356. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.326-356.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schumacher MA, et al. Structural mechanisms of QacR induction and multidrug recognition. Science. 2001;294(5549):2158–2163. doi: 10.1126/science.1066020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellinzoni M, et al. Structural plasticity and distinct drug-binding modes of LfrR, a mycobacterial efflux pump regulator. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(24):7531–7537. doi: 10.1128/JB.00631-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petoukhov MV, Svergun DI. Global rigid body modeling of macromolecular complexes against small-angle scattering data. Biophys J. 2005;89(2):1237–1250. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.064154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svergun DI. Restoring low resolution structure of biological macromolecules from solution scattering using simulated annealing. Biophys J. 1999;76(6):2879–2886. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77443-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Svergun DI, Petoukhov MV, Koch MH. Determination of domain structure of proteins from X-ray solution scattering. Biophys J. 2001;80(6):2946–2953. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho H, Bernhardt TG. 2013. Identification of the SlmA active site responsible for blocking bacterial cytokinetic ring assembly over the chromosome. PLOS Genet 9(2):e1003304.

- 31.Thanedar S, Margolin W. FtsZ exhibits rapid movement and oscillation waves in helix-like patterns in Escherichia coli. Curr Biol. 2004;14(13):1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Libby EA, Roggiani M, Goulian M. Membrane protein expression triggers chromosomal locus repositioning in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(19):7445–7450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109479109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Männik J, et al. Robustness and accuracy of cell division in Escherichia coli in diverse cell shapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(18):6957–6962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120854109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.