Abstract

In photosynthesis, photosystem II evolves oxygen from water by the accumulation of photooxidizing equivalents at the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC). The OEC is a Mn4CaO5 cluster, and its sequentially oxidized states are termed the Sn states. The dark-stable state is S1, and oxygen is released during the transition from S3 to S0. In this study, a laser flash induces the S1 to S2 transition, which corresponds to the oxidation of Mn(III) to Mn(IV). A broad infrared band, at 2,880 cm−1, is produced during this transition. Experiments using ammonia and 2H2O assign this band to a cationic cluster of internal water molecules, termed “W5+.” Observation of the W5+ band is dependent on the presence of calcium, and flash dependence is observed. These data provide evidence that manganese oxidation during the S1 to S2 transition results in a coupled proton transfer to a substrate-containing, internal water cluster in the OEC hydrogen-bonded network.

Internal proton transfer reactions play important catalytic roles in many integral membrane proteins. In these enzymes, including bacteriorhodopsin, light-driven or redox-coupled proton-transfer reactions lead to the production of a transmembrane, electrochemical gradient. Amino acid side chains often participate in the acid/base chemistry that occurs in proton-transfer pathways. However, internal bound water clusters can also play essential roles as proton donors or acceptors (reviewed in ref. 1).

In photosystem II (PSII), proton transfer contributes to the generation of a transmembrane potential, and chemical protons are released from the substrate, water, during the light-driven reactions that produce molecular oxygen (2). PSII is a complex membrane protein consisting of both integral, membrane-spanning subunits and extrinsic subunits (3). A monomeric unit of PSII consists of at least 20 distinct protein subunits, which are composed of 17 integral subunits and 3 extrinsic polypeptides (4, 5). The primary subunits that make up the reaction center and bind most of the redox-active cofactors are D1, D2, CP43, and CP47. The light-induced electron transfer pathway in the reaction center involves the dimeric chlorophyll (chl) donor, P680, and accessory chl molecules. One light-induced charge separation oxidizes the primary donor, P680, and reduces a bound plastoquinone acceptor, QA. P680+ oxidizes a tyrosine residue, YZ, Y161 of the D1 polypeptide, which is a powerful oxidant. YZ• oxidizes the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) on each photoinduced charge separation (reviewed in ref. 6).

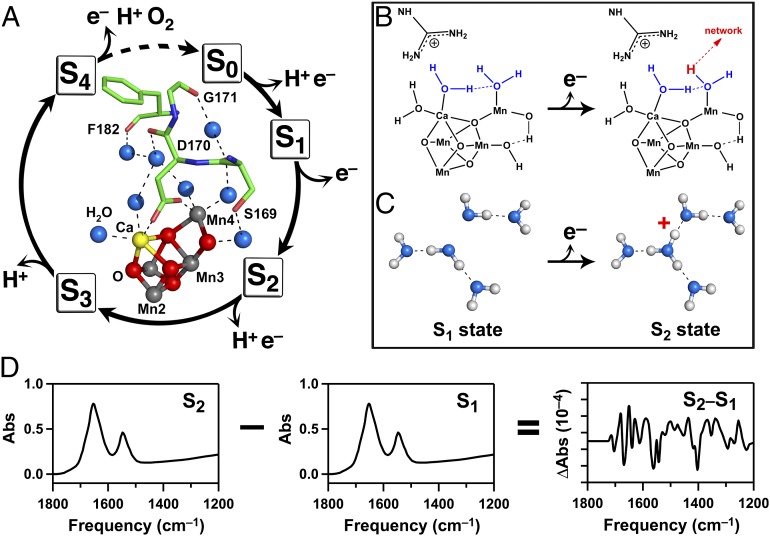

The OEC is a Mn4CaO5 cluster (Fig. 1 A, Inset) (5). Oxygen release from the OEC fluctuates with period four (7). The OEC cycles through five sequentially oxidized states, called the Sn states. A single flash given to a dark-adapted sample (S1 state) generates the S2 state (Fig. 1A), which corresponds to the oxidation of Mn(III) to Mn(IV) (8). Subsequent flashes advance the remaining manganese ions to higher oxidation states, with an accompanying deprotonation of two bound water molecules. The O–O bond is formed, and oxygen is evolved during the transition from S3 to S0 (Fig. 1A). Despite decades of study, many aspects of the water-oxidation mechanism remain to be elucidated. In this work, we obtain previously unknown information concerning proton-coupled electron transfer reactions during the S1-to-S2 and other S-state transitions.

Fig. 1.

Photosynthetic water oxidation and protonation of a water cluster during the S1-to-S2 transition. (A) S-state cycle of photosynthetic water oxidation (7). (A, Inset) Predicted hydrogen-bond network of water molecules in the OEC of PSII (5). Amino acids are shown as sticks. Oxygen atoms of water molecules are shown in blue, with hydrogen bonds to peptide carbonyl groups shown as dashed lines. (B) Mechanism proposed for deprotonation of a terminal water ligand during the S1-to-S2 transition in PSII (14). Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines. Putative substrate water molecules are shown in blue. (C) Schematic diagram showing the formation of a cationic water cluster, W5+, on the S1 to S2 transition in PSII. (D) Diagram showing method generating the reaction-induced FTIR spectrum, corresponding to the S2-minus-S1 spectrum. Difference FTIR spectra for the other S-state transitions are produced with two (S3-minus-S2), three (S0-minus-S3), or four (S1–S0) flashes (see cycle in A).

Many mechanisms have been proposed for photosynthetic oxygen evolution (reviewed in refs. 9–13). Fig. 1B shows a possible mechanism for the S1-to-S2 transition based on quantum mechanics (QM)/molecular mechanics (MM) calculations (ref. 14; but also see ref. 13). The calcium ion in the metal cluster has been proposed to bind a substrate water molecule and to activate the substrate (15–18). Deprotonation of terminal water ligands is important in decreasing the midpoint potential necessary for oxygen evolution, which is mediated by YZOH/YZ• (midpoint potential; 1V vs. normal hydrogen electrode) and which, therefore, occurs with a low driving force (19).

A hydrogen-bonding network containing bound water molecules (Fig. 1 A, Inset) has been assigned in a recent X-ray structure (5). This network has been hypothesized to play a role in the water-oxidizing cycle (18, 20). Recent reaction-induced FTIR studies of the S1-to-S2 transition showed that the frequencies of hydrogen-bonded amide C=O groups were markers of hydrogen-bonding changes in the network. In another approach, the recombination kinetics of YZ• were used as a probe of electrostatic changes in the network in the S2 and S0 states (21, 22). In both studies, ammonia, a substrate-based inhibitor (23–25), was used to perturb hydrogen bonding in the OEC and was shown to have significant effects on the spectroscopic signals (18, 20, 22).

Proton-coupled electron-transfer reactions occur during the S-state cycle (11, 12). Although the S1-to-S2 transition is not accompanied by a net proton release to sucrose-containing buffers, proton release accompanies the other S-state transitions (26). Proton-transfer pathways have been proposed based on site-directed mutagenesis and the 3D arrangement of amino acid side chains (5, 27, 28). However, the idea that the water network itself may act as a proton acceptor has not yet been critically evaluated. Spectroscopic signals from protonated water clusters (Fig. 1C) have been identified in model compounds (29) and in proteins (30–33). The OH frequencies of these clusters are red-shifted from bulk water, with a frequency related to the size of the cluster (34, 35). For example, in bacteriorhodopsin, a cluster of internal water molecules acts as a proton donor during the L-to-M transition (36, 37).

Here, spectroscopic evidence for the formation of a cationic water cluster, termed W5+, during the S1-to-S2 transition is presented (Fig. 1C). The results suggest that deprotonation of a terminal water ligand or a μ–OH bridge occurs on this transition, that the W5 water cluster acts as a proton acceptor, and that this proton is not released to bulk solvent until later S states. The formation of the protonated cluster is shown to be dependent on temperature, S state, and calcium, consistent with a role for an internal water cluster in photosynthetic oxygen evolution.

Results

Reaction-induced FTIR spectra, associated with the S1-to-S2 transition, were constructed from data recorded before and after an actinic flash (Fig. 1D). Light-induced difference spectra for the other S state transitions (Fig. 1A) were constructed similarly. This technique was originally described in refs. 38 and 39, where it was established that the spectra exhibit period four oscillations in frequency and amplitude. Under the conditions used here (18, 20), these spectra reflect long-lived structural dynamics in the OEC (40, 41).

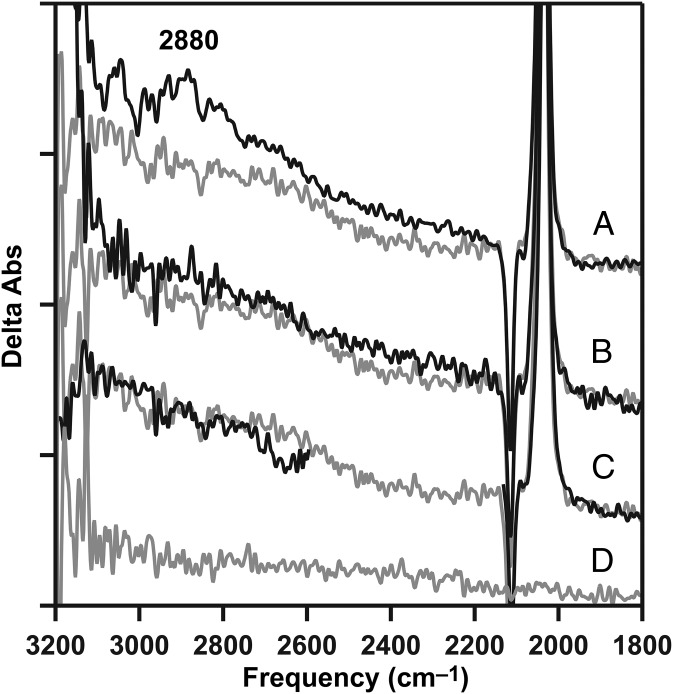

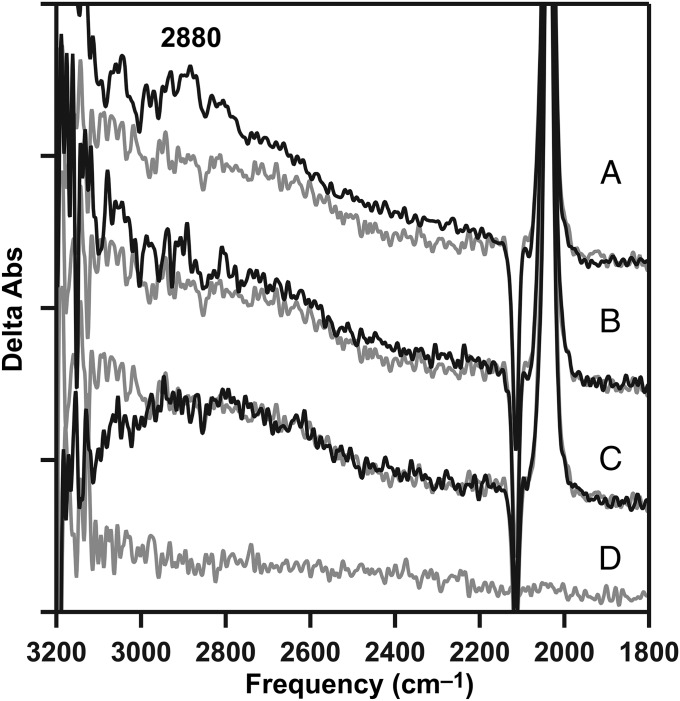

In Fig. 2A (black), reaction-induced FTIR spectra were acquired from a calcium-containing preparation, termed calcium PSII. The PSII preparation was isolated from market spinach by using Triton X-100 and octylthioglucoside (42, 43) and exhibited high steady-state rates of oxygen evolution activity (Table S1). To make the samples used in these studies, calcium was removed and then reconstituted, restoring activity (Table S1). This method was recently described (18). The reaction-induced FTIR spectrum reflects the S2-minus-S1 transition in this preparation. The 3,200- to 1,800-cm−1 region of this spectrum exhibits a broad band at 2,880 cm−1, in addition to the 2,116/2,038 cm−1 CN bands from the potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide couple. This couple is used to oxidize the quinone acceptor after the flash and can be used as a marker of charge separation. The 1,800- to 1,200-cm−1 region of this spectrum is described and presented in ref. 18.

Fig. 2.

Reaction-induced FTIR detection of the protonated water cluster, W5+, produced by the S1-to-S2 transition. (A) Positive 2,880-cm−1 band from the cationic water cluster in calcium PSII (black), compared with calcium-depleted (gray). (B) Calcium PSII after treatment with 100 mM ammonia (black), compared with calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from A, gray). (C) Calcium PSII after exchange into 2H2O buffer (black), compared with calcium-depleted in 1H2O buffer (gray; repeated from A, gray). The O–D stretching band in C, black has been omitted for clarity. The calcium-depleted difference spectrum was acquired with a single flash to a dark-adapted sample and corresponds to S2′-minus-S1. (D) Baseline (S1-minus-S1) acquired from dark-adapted, calcium-depleted PSII. Spectra are averages of 31 (A, black), 16 (B, black), 12 (C, black), and 15 (A–D, gray) samples. y axis ticks represent 1 × 10−4 absorbance units. The temperature was 263 K.

In Fig. 2A (gray), the spectrum was acquired from a calcium-depleted PSII preparation, which is inactive in oxygen evolution but able to undergo part of the cycle—i.e., a S1-to-S2′ transition (see ref. 18 and references therein). This spectrum does not exhibit the 2,880-cm−1 band, but does show the ferricyanide/ferrocyanide CN bands, reflecting photoinduced charge separation.

The frequency and amplitude of the 2,880-cm−1 band in calcium PSII were reproducible, as shown by data in Fig. S1, and exhibited significant intensity above the baseline, as deduced from a background recorded before the flash (Fig. 2D).

Previously, experimental (44) and theoretical (34, 35) methods have assigned broad infrared features in the 2,900-cm−1 region to the protonation of small clusters of four or five hydrogen-bonded water molecules. To test whether the 2,880-cm−1 band in Fig. 2A (black) originates from the water network in the OEC, ammonia treatment (Fig. 2B, black) and 2H2O exchange (Fig. 2C, black) were used. These treatments disrupt the water network by intercalation (ammonia) or by alterations in pKa (2H2O), leading to changes in hydrogen-bond strength (18). In Fig. 2 B and C (black), ammonia-treated and 2H2O-exchanged PSII failed to exhibit the 2,880-cm−1 band. This result supports the assignment of this spectral feature to a water cluster in the hydrogen-bonded network.

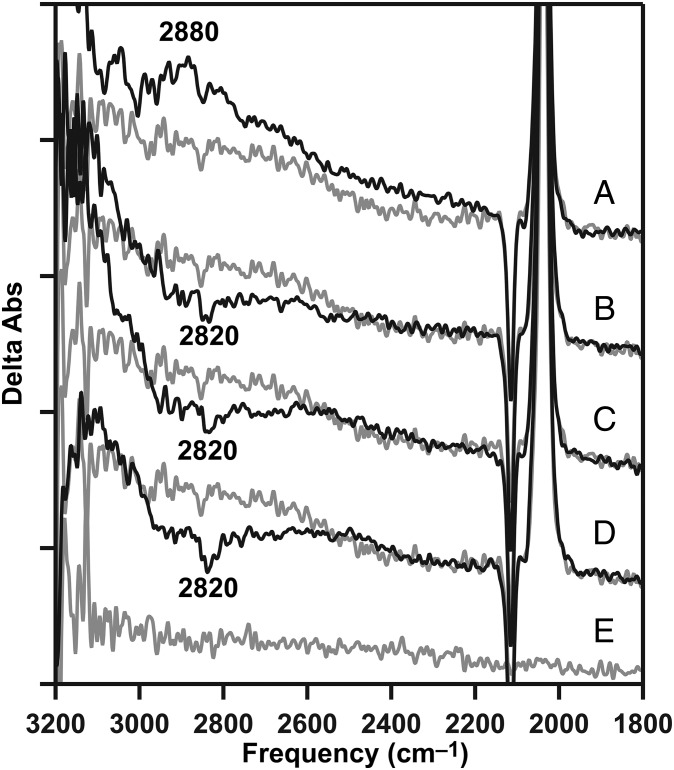

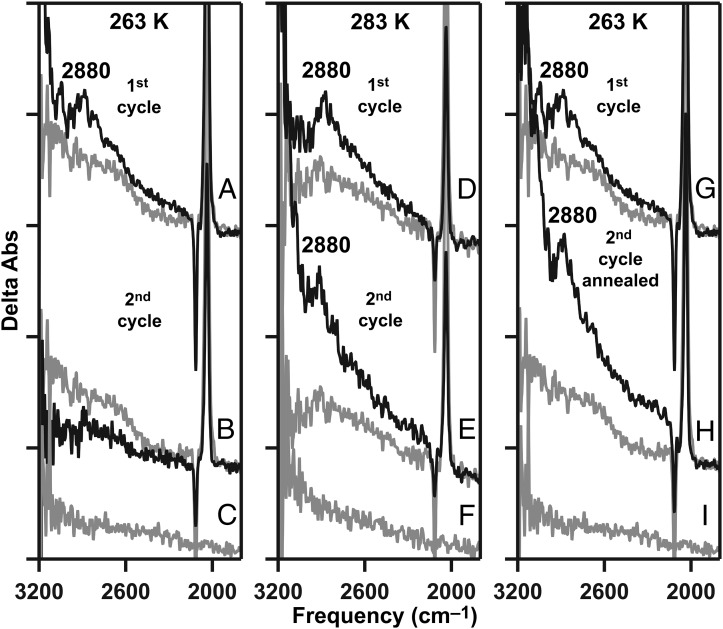

To test whether the 2,880-cm−1 band was observed in an S-state–dependent manner at 263 K, reaction-induced FTIR spectra were acquired before and after a second flash, generating the S3 state (Fig. 3B, black) in calcium PSII. The S3-minus-S2 difference spectrum exhibited a negative 2,880-cm−1 band (Fig. 3B, black). A negative band was also observed on the third flash, corresponding to S0-minus-S3 (Fig. 3C, black), and on the fourth flash, corresponding mainly to S1-minus-S0, but with mixing of other S states, due to misses (22) (Fig. 3D, black). Consistent with significant mixing, on the fifth flash, there was no difference spectrum, even in the midinfrared (1,800–1,200 cm−1), but dark adaptation of the sample regenerated a light-induced difference spectrum (see below). In this PSII preparation, observation of the signal at pH 7.5 required removal and reconstitution of calcium; the signal could also be observed under various conditions at pH 6.0. We conclude the cationic water cluster appears during the S1-to-S2 transition and disappears during the S2-to-S3, S3-to-S0, and S0-to-S1 transitions at 263 K. The disappearance most likely reflects loss of the proton from internal waters to bulk solvent. The change in the bulk solvent is not directly detectable because the contribution would be in the saturated spectral region corresponding to the OH/NH band (3,600 cm−1).

Fig. 3.

Flash dependence of the protonated water cluster band (from W5+) at 263 K. (A) Positive 2,880-cm−1 cationic water cluster band in the calcium S2-minus-S1 difference spectrum (black), generated by a single flash after dark adaptation, compared with calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from Fig. 2A, gray). (B) Calcium S3-minus-S2 spectrum (black), generated by two actinic flashes after dark adaptation, compared with calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from A, gray). (C) Calcium S0-minus-S3 spectrum (black), generated by three actinic flashes, compared with the calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from A, gray). (D) Calcium S1-minus-S0 spectrum (black), generated by four actinic flashes after dark adaptation, compared with calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from A, gray). The calcium-depleted difference spectrum was acquired with a single flash to a dark-adapted sample and corresponds to S2′-minus-S1. (E) Baseline (S1-minus-S1) acquired from dark-adapted, calcium-depleted PSII. Spectra are averages of 31 (A–D, black) and 15 (A–E, gray) samples. y axis ticks represent 1 × 10−4 absorbance units.

At 283 K, the positive 2,880-cm−1 band (Fig. 4A, black) was also observed in calcium PSII after a single flash. The frequency and amplitude of the 2,880-cm−1 band were reproducible at this temperature, as well as 263 K, as shown by data in Fig. S2. However, there was no significant negative band detected on subsequent flashes (Fig. 4 B–D, black), compared with a calcium-depleted control at the same temperature (Fig. 4 A–D, gray). This failure to observe the negative band may be attributable to a more rapid transfer of the proton to bulk solvent at this temperature.

Fig. 4.

Flash dependence of the protonated water cluster band (from W5+) at 283 K. (A) Positive 2,880-cm−1 cationic water cluster band in the calcium S2-minus-S1 difference spectrum (black), generated by a single flash after dark adaptation, compared with calcium-depleted (gray). (B) Calcium S3-minus-S2 spectrum (black), generated by two actinic flashes after dark adaptation, compared with calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from A, gray). (C) Calcium S0-minus-S3 spectrum (black), generated by three actinic flashes, compared with the calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from A, gray). (D) Calcium S1-minus-S0 spectrum (black), generated by four actinic flashes after dark adaptation, compared with calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from A, gray). The calcium-depleted difference spectrum was acquired with a single flash to a dark-adapted sample and corresponds to S2′-minus-S1. (E) Baseline (S1-minus-S1) acquired from dark-adapted, calcium-depleted PSII. Spectra are averages of 21 (A–D, black) and 15 (A–E, gray) samples. y axis ticks represent 1 × 10−4 absorbance units.

Dark adaptation of calcium PSII resets the S-state cycle to the S1 state. A single flash is expected to give the S1-to-S2 transition again on this second reaction cycle. As shown in Fig. 5B (black), on the second cycle, the 2,880-cm−1 band was not observed at 263 K (Fig. 5, Left). However, at 283 K, the positive 2,880-cm−1 band (Fig. 5E, black) was reproduced after dark adaptation (Fig. 5, Center). These data can be rationalized if the 2,880-cm−1 band represents contributions from a water cluster that includes substrate water molecules. During the first reaction cycle at 263 K (Fig. 5, Left), these substrate molecules are oxidized and produce molecular oxygen. Because 263 K may be below the glass transition temperature, the diffusion of new water molecules into an internal site may be slow compared with the timescale of the experiment, which cycles through all of the S states within 60 s. Alternatively, the water diffusion reaction may be conformationally gated (reviewed in ref. 6) and, therefore, inhibited at 263 K.

Fig. 5.

Annealing, the S2-minus-S1 spectrum, and the protonated water cluster band (from W5+) in calcium PSII. The temperature of data acquisition was 263 K (A–C and G–I) or 283 K (D–F). Spectra were acquired after a single flash on the first reaction cycle (A, D, and G, black) or on a second cycle (B, E, and H, black). (H, black) The sample was annealed to 283 K between the first and second reaction cycles. (A, B, D, E, G, and H, gray) The S2′-minus-S1 spectra were acquired from a calcium-depleted sample (first cycle) at the temperatures indicated. The baselines (S1-minus-S1) in a calcium-depleted sample are shown in C, F, and I at the indicated temperatures. Spectra are averages of 31 (A, black), 10 (B, black), 21 (D, black), 10 (E, black), 31 (G, black), 10 (H, black), and 15 (A–I, gray) samples. y axis ticks represent 1 × 10−4 absorbance units.

To test this idea, the FTIR experiment was conducted at 263 K (Fig. 5G, black); the calcium PSII sample was annealed at 283 K, above the glass transition, for 10 min between the flash cycles; and the sample was recooled to 263 K (Fig. 5, Right). In this case, the 2,880-cm−1 band reappeared during the S1-to-S2 transition (Fig. 5H, black). These results support the attribution of the 2,880-cm−1 band to a protonated water network, which contains or is influenced by binding and subsequent oxidation of substrate water molecules.

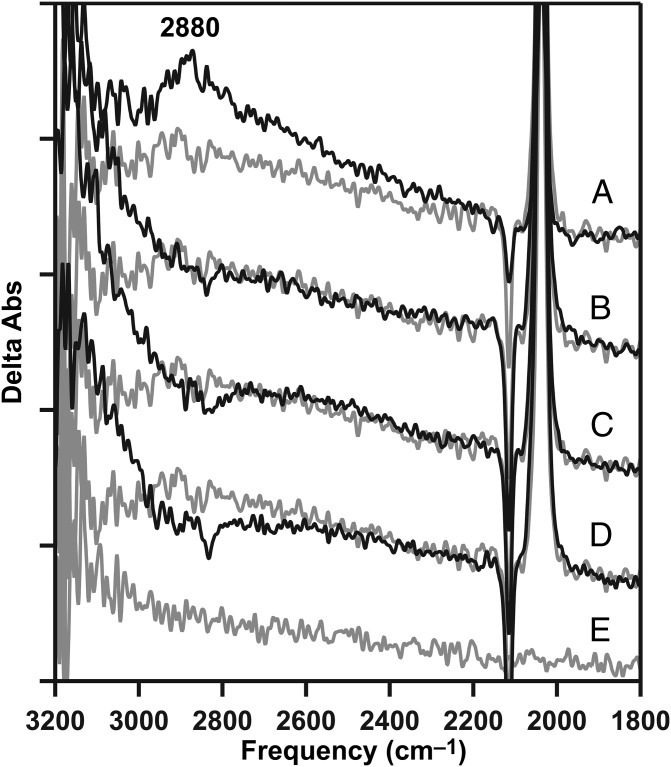

As shown above (Figs. 2A and 4A, black), the 2,880-cm−1 band was produced in the S2 state, which was generated in calcium PSII, but not in the S2′ state generated in calcium-depleted PSII. To test the role of calcium in the formation of this band, strontium was substituted into the OEC (18). Strontium-reconstituted preparations (strontium PSII) were active in oxygen evolution, but at a lower steady-state rate [1,000 μmol O2 (mg chl⋅h)−1], compared with calcium PSII [1,200 μmol O2 (mg chl⋅h)−1], as described (18) and as expected (17). Interestingly, in strontium PSII, the 2,880-cm−1 band was not observed (Fig. 6B), although these preparations were active in oxygen evolution, and the S1-to-S2 transition occurred (18). The 2,880-cm−1 band also was not observed in magnesium-treated preparations (Fig. 6C); magnesium did not restore activity, but a S1-to-S2′ transition occurs (18).

Fig. 6.

Inability of strontium or magnesium to support the formation of a 2,880-cm−1 band from the protonated water cluster, W5+. (A) Positive 2,880-cm−1 cationic water cluster band in the calcium S2-minus-S1 difference spectrum (black), compared with calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from Fig. 2A, gray). (B) Strontium S2-minus-S1 spectrum (black), compared with calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from A, gray). (C) S2′-minus-S1 spectrum after treatment with magnesium (black), compared with calcium-depleted (gray; repeated from A, gray). The calcium-depleted difference spectrum was acquired with a single flash to a dark-adapted sample and corresponds to S2′-minus-S1. (D) Baseline (S1-minus-S1) acquired from a dark-adapted strontium PSII sample. Spectra are averages of 31 (A, black), 16 (B, black), 17 (C, black), 16 (D, gray), and 15 (A–C, gray) samples. y axis ticks represent 1 × 10−4 absorbance units. The temperature was 263 K.

Previously, flash-dependent absorption at 3,618/3,585 cm−1 (45), attributed to an individual water molecule, and broad baseline displacements at 2,500 cm−1 (46), attributed to proton polarizability changes, have been reported in thermophilic, cyanobacterial PSII. We present these spectral regions in Fig. S3. As shown, the data exhibited no significant intensity at 3,618/3,585 cm−1, when this region was compared with the baseline (Fig. S3 A–E). Also, there were no systematic, flash-dependent shifts in the baseline at 2,500 cm−1 in these data (Fig. S3 F–J).

Discussion

This paper describes a previously unidentified 2,880-cm−1 FTIR band, produced in the S2 state of the photosynthetic OEC. The frequency and breadth of the band suggests assignment to a protonated water cluster, with an OH stretching frequency that is red-shifted from that of bulk water. The intensity of this band changed with flash number, consistent with an association with the water-oxidizing cycle. The 2,880-cm−1 band was not observed after the addition of ammonia or 2H2O, which are known to disrupt hydrogen-bonding interactions in the OEC water network (18, 20, 22). These results support the assignment of the 2,880-cm−1 band to a small, cationic cluster of internal water molecules, formed when Mn is oxidized during the S1-to-S2 transition (Fig. 1C). At 263 K, the band decreased in intensity during the S2-to-S3, S3-to-S0, and S0-to-S1 transitions, suggesting that the water cluster deprotonates during this part of the cycle. The band was also associated with the S1-to-S2 transition at a higher temperature, 283 K, but negative bands were not observed on subsequent flashes. This observation suggests that the lifetime of the cationic water cluster is short at higher temperatures.

Interestingly, the 2,880-cm−1 band was not regenerated with a second light-induced reaction cycle, corresponding to the fifth flash after dark adaptation, at a temperature below the sample's glass transition temperature (263 K). Oxygen is released and substrate water molecules are consumed during this first reaction cycle. The viscosity of sucrose has been shown to increase with decreasing temperature (47). Therefore, we hypothesized that the diffusion of water might be too slow to replace the substrate at this low temperature. To test this hypothesis, the 263 K sample was subjected to a reaction cycle and then annealed at 283 K. This treatment caused the reappearance of the band on a second reaction cycle (fifth flash after dark adaptation) at 263 K. These results suggest that reobservation of the band requires diffusion of water into the OEC. Together, these results support the conclusion that the water cluster contains, or is influenced by, binding of substrate water.

Previously, bands from internal, protonated water clusters have been proposed to play functional roles in several proteins that carry out proton-transfer reactions. Examples include bacteriorhodopsin (30, 48, 49), nitric oxide reductase (33), ATP synthase (32), and cytochrome c oxidase (31). In each of these systems, protons are pumped across a membrane. This proton transfer is facilitated by an internal water network. The results presented here are consistent with a role for a water cluster as a proton acceptor at one step in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving cycle.

The 2,880-cm−1 band was not observed in strontium PSII or magnesium-treated PSII. These data are consistent with a role for calcium in production of the protonated cluster. Models for water oxidation propose that calcium activates a substrate water molecule, which may carry out a nucleophilic attack on a Mn-oxyl intermediate during the S3-to-S0 transition (for example, see ref. 14). Mass spectrometry experiments have shown that calcium may bind a slowly exchanging water molecule (16). Recently, a structure of strontium-containing, cyanobacterial PSII (50) suggested that the hydrogen-bond distances between strontium and water molecules are different from the distances observed in calcium PSII. This strontium-containing structure is consistent with our previous FTIR results, which showed a difference in electrostatic interactions in the water network when strontium is bound. Peptide carbonyl frequency shifts, observed in strontium PSII, were used to support this interpretation (18). Therefore, failure to observe the 2,880-cm−1 band in strontium PSII (this work) may be due to a shift in the size of the water cluster in the strontium-containing OEC. In gas phase studies, changes in the size and amount of proton delocalization dramatically altered the frequency and intensity of such proton continuum bands (44).

There is no net proton release during the first S-state transition in sucrose-containing buffers (26). However, density functional theory-derived models suggest that a deprotonation event occurs from a μ–oxo bridge connecting Ca and Mn (12, 13), concomitant with Mn4 oxidation and binding of a second substrate water molecule. Alternatively, QM/MM-derived models (Fig. 1B) suggest that a terminal water molecule is deprotonated (14), concomitant with oxidation of Mn3, which does not bind substrate. Thus, both computational approaches suggest that a proton transfer is coupled with electron transfer during the S1-to-S2 transition. Our results provide a rationalization for the failure to observe proton release on this transition. We propose that an excess positive charge is stored in the water network, under some conditions, and is not released to the bulk until later in the cycle.

The size of the protonated water cluster is of interest. Theoretical (34, 35) and experimental (44) investigations demonstrate a correlation between O–O bond distance, number of water molecules, and frequency. The 2,880-cm−1 frequency observed here is most consistent with a cluster of five hydrogen-bonded water molecules, termed here W5, which comprises a hydronium ion core (Fig. 1C) and which occupies a number of low-energy conformations (44). The 1.9-Å PSII structure shows that a network of bound water molecules connects the OEC to peptide carbonyl groups (Fig. 1 A, Inset) and provides an exit pathway to the lumen (5). The protonated water cluster, described here, may be a component of this network, but, to explain our results, proton transport to the solvent-exposed, luminal surface must be slow at 263 K. This slow rate of proton transport could be due to a disruption in network continuity or to a conformational gate, which limits proton movement, at 263 K.

In summary, we present spectroscopic evidence that a cluster of five water molecules, W5, accepts a proton during the S1-to-S2 transition of the water-oxidizing cycle. Our results are consistent with deprotonation of a terminal water ligand or a μ–OH bridge during this transition. However, these data suggest that the proton is not released to solvent until later in the water-oxidizing cycle. Proton transfer to this internal water cluster exhibited calcium dependence. Perturbation of the hydrogen-bonded water network with ammonia or 2H2O eliminated the band. These experiments provide evidence that a hydrogen-bonded water cluster, W5, serves as a proton acceptor in photosynthetic oxygen evolution.

Materials and Methods

PSII isolation methods are described in SI Materials and Methods. Reaction-induced FTIR difference spectroscopy was performed as described (18, 20, 41, 51) at 263 or 283 K and at pH 7.5. Briefly, a calcium-depleted sample was thawed and pelleted. The sample was resuspended in the appropriate buffer for a third time. K3[Fe(CN)6] (7 mM) was added from a 100 mM stock in 1H2O or 2H2O, where indicated. NH4Cl (100 mM) was added from a 3 M buffered stock, and CaCl2 (20 mM) was added from a 3 M buffered stock solution. Control samples contained NaCl (100 mM) instead of ammonia. For samples containing calcium, magnesium, or strontium, the chloride salt was added from a 3 M buffered stock solution to give a final concentration of 20 mM. NaCl was added from a 3 M buffered stock solution to yield a final chloride concentration of 155 mM in all samples. After additions, the sample was centrifuged a final time (50,000 × g for 15 min) to produce a pellet. The residual EGTA concentration was estimated to be 0.6 mM. The total incubation time, which included centrifugation, preparation of the sample, and dark adaptation, was held constant and limited to 1 h. The pelleted sample was spread on a CaF2 window and dried under N2 gas to give an O–H stretching (3,370 cm−1) to amide II (1,550 cm−1) absorbance ratio of >3. Samples were sandwiched with a second CaF2 window. Window edges were sealed with grease and wrapped tightly with parafilm to prevent sample dehydration over the course of the experiment.

Acquisition parameters for FTIR spectroscopy were as follows: 8-cm−1 spectral resolution; four levels of zero filling; Happ–Genzel apodization function; 60-KHz mirror speed; and Mertz phase correction. Samples were preflashed with a single saturating 532-nm laser flash at 40 mJ/cm2 power density and were dark-adapted for 20 min. Dark-adapted samples were given a train of actinic flashes, followed by 15 s of rapid scan data collection (first reaction cycle). In some cases, there was a second 20-min dark adaptation, and a second round of flashes was given (second reaction cycle). Difference spectra were constructed by ratio of single-channel data, which was taken before and after the actinic flash. Rapid scan data were normalized to an amide II intensity of 0.5 absorbance units to eliminate any small differences in sample path length (∼6 μm). The intensity of the amide II band was determined from an infrared absorption spectrum, which was collected against an open beam background.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Molecular and Cellular Biosciences Grant 08-42246 (to B.A.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1306532110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kötting C, Gerwert K. Proteins in action monitored by time-resolved FTIR spectroscopy. ChemPhysChem. 2005;6(5):881–888. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson N, Yocum CF. Structure and function of photosystems I and II. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:521–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bricker TM, Roose JL, Fagerlund RD, Frankel LK, Eaton-Rye JJ. The extrinsic proteins of Photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817(1):121–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kashino Y, et al. Proteomic analysis of a highly active photosystem II preparation from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 reveals the presence of novel polypeptides. Biochemistry. 2002;41(25):8004–8012. doi: 10.1021/bi026012+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen JR, Kamiya N. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature. 2011;473(7345):55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature09913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barry BA. Proton coupled electron transfer and redox active tyrosines in Photosystem II. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2011;104(1–2):60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Joliot P, Kok B (1975) Oxygen evolution in photosynthesis. Bioenergetics of Photosynthesis, ed Govindjee (Academic, New York), pp 387–412.

- 8.Haumann M, Grabolle M, Neisius T, Dau H. The first room-temperature X-ray absorption spectra of higher oxidation states of the tetra-manganese complex of photosystem II. FEBS Lett. 2002;512(1–3):116–120. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dau H, Zaharieva I, Haumann M. Recent developments in research on water oxidation by photosystem II. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16(1–2):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho FM. Structural and mechanistic investigations of photosystem II through computational methods. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817(1):106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito T, et al. Possible mechanisms of water splitting reaction based on proton and electron release pathways revealed for CaMn4O5 cluster of PSII refined to 1.9 angstrom X-ray resolution. Int J Quantum Chem. 2012;112(1):253–276. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegbahn PEM. Mechanisms for proton release during water oxidation in the S2 to S3 and S3 to S4 transitions in photosystem II. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14(14):4849–4856. doi: 10.1039/c2cp00034b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegbahn PEM. Water oxidation mechanism in photosystem II, including oxidations, proton release pathways, O-O bond formation and O(2) release. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sproviero EM, Gascón JA, McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW, Batista VS. Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics study of the catalytic cycle of water splitting in photosystem II. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(11):3428–3442. doi: 10.1021/ja076130q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vrettos JS, Stone DA, Brudvig GW. Quantifying the ion selectivity of the Ca2+ site in photosystem II: Evidence for direct involvement of Ca2+ in O2 formation. Biochemistry. 2001;40(26):7937–7945. doi: 10.1021/bi010679z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendry G, Wydrzynski T. (18)O isotope exchange measurements reveal that calcium is involved in the binding of one substrate-water molecule to the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2003;42(20):6209–6217. doi: 10.1021/bi034279i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yocum CF. The calcium and chloride requirements of the O2 evolving complex. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252(3–4):296–305. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polander BC, Barry BA. Calcium and the hydrogen-bonded water network in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. J Phys Chem Lett. 2013;4(5):786–791. doi: 10.1021/jz400071k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren JJ, Winkler JR, Gray HB. Redox properties of tyrosine and related molecules. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(5):596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polander BC, Barry BA. A hydrogen-bonding network plays a catalytic role in photosynthetic oxygen evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(16):6112–6117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keough JM, Jenson DL, Zuniga AN, Barry BA. Proton coupled electron transfer and redox-active tyrosine Z in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(29):11084–11087. doi: 10.1021/ja2041139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keough JM, Zuniga AN, Jenson DL, Barry BA. Redox control and hydrogen bonding networks: Proton-coupled electron transfer reactions and tyrosine Z in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117(5):1296–1307. doi: 10.1021/jp3118314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandusky PO, Yocum CF. The mechanism of amine inhibition of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. FEBS Lett. 1983;162(2):339–343. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Britt RD, Zimmermann J-L, Sauer K, Klein MP. Ammonia binds to the catalytic Mn of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II: Evidence by electron spin-echo envelope modulation spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:3522–3532. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boussac A, Rutherford AW, Styring S. Interaction of ammonia with the water splitting enzyme of photosystem II. Biochemistry. 1990;29(1):24–32. doi: 10.1021/bi00453a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Junge W, Haumann M, Ahlbrink R, Mulkidjanian A, Clausen J. Electrostatics and proton transfer in photosynthetic water oxidation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 2002;357(1426):1407–1420. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho FM. Uncovering channels in photosystem II by computer modelling: Current progress, future prospects, and lessons from analogous systems. Photosynth Res. 2008;98(1–3):503–522. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dilbeck PL, et al. The D1-D61N mutation in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 allows the observation of pH-sensitive intermediates in the formation and release of O₂ from photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2012;51(6):1079–1091. doi: 10.1021/bi201659f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kristof W, Zundel G. Structurally symmetrical, easily polarizable hydrogen bonds between side chains in proteins and proton-conducting mechanisms. III. Biopolymers. 1980;19(10):1753–1769. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garczarek F, Gerwert K. Functional waters in intraprotein proton transfer monitored by FTIR difference spectroscopy. Nature. 2006;439(7072):109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature04231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu JC, Sharpe MA, Qin L, Ferguson-Miller S, Voth GA. Storage of an excess proton in the hydrogen-bonded network of the d-pathway of cytochrome C oxidase: Identification of a protonated water cluster. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(10):2910–2913. doi: 10.1021/ja067360s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preiss L, Yildiz O, Hicks DB, Krulwich TA, Meier T. A new type of proton coordination in an F(1)F(o)-ATP synthase rotor ring. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(8):e1000443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pisliakov AV, Hino T, Shiro Y, Sugita Y. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal proton transfer pathways in cytochrome C-dependent nitric oxide reductase. PLOS Comput Biol. 2012;8(8):e1002674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Headrick JM, et al. Spectral signatures of hydrated proton vibrations in water clusters. Science. 2005;308(5729):1765–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.1113094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulig W, Agmon N. A ‘clusters-in-liquid’ method for calculating infrared spectra identifies the proton-transfer mode in acidic aqueous solutions. Nat Chem. 2013;5(1):29–35. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathias G, Marx D. Structures and spectral signatures of protonated water networks in bacteriorhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(17):6980–6985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609229104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freier E, Wolf S, Gerwert K. Proton transfer via a transient linear water-molecule chain in a membrane protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(28):11435–11439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104735108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noguchi T, Sugiura M. Flash-induced Fourier transform infrared detection of the structural changes during the S-state cycle of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2001;40(6):1497–1502. doi: 10.1021/bi0023807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hillier W, Babcock GT. S-state dependent Fourier transform infrared difference spectra for the photosystem II oxygen evolving complex. Biochemistry. 2001;40(6):1503–1509. doi: 10.1021/bi002436x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barry BA, et al. Time-resolved vibrational spectroscopy detects protein-based intermediates in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(19):7288–7291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600216103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Riso A, Jenson DL, Barry BA. Calcium exchange and structural changes during the photosynthetic oxygen evolving cycle. Biophys J. 2006;91(5):1999–2008. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berthold DA, Babcock GT, Yocum CF. A highly resolved, oxygen-evolving photosystem II preparation from spinach thylakoid membranes—EPR and electron-transport properties. FEBS Lett. 1981;134(2):231–234. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mishra RK, Ghanotakis DF. Selective extraction of CP26 and CP29 proteins without affecting the binding of the extrinsic proteins (33, 23 and 17 kDa) and the DCMU sensitivity of a photosystem II core complex. Photosynth Res. 1994;42(1):37–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00019056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Douberly GE, Walters RS, Cui J, Jordan KD, Duncan MA. Infrared spectroscopy of small protonated water clusters, H(+)(H2O)n (n = 2-5): Isomers, argon tagging, and deuteration. J Phys Chem A. 2010;114(13):4570–4579. doi: 10.1021/jp100778s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noguchi T, Sugiura M. Structure of an active water molecule in the water-oxidizing complex of photosystem II as studied by FTIR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2000;39(36):10943–10949. doi: 10.1021/bi001040i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noguchi T, Suzuki H, Tsuno M, Sugiura M, Kato C. Time-resolved infrared detection of the proton and protein dynamics during photosynthetic oxygen evolution. Biochemistry. 2012;51(15):3205–3214. doi: 10.1021/bi300294n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zobrist B, et al. Ultra-slow water diffusion in aqueous sucrose glasses. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13(8):3514–3526. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01273d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olejnik J, Brzezinski B, Zundel G. A proton pathway with large proton polarizability and the proton pumping mechanism in bacteriorhodopsin—Fourier transform difference spectra of photoproducts of bacteriorhodopsin and of its pentademethyl analog. J Mol Struct. 1992;271(3):157–173. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heberle J. Proton transfer reactions across bacteriorhodopsin and along the membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458(1):135–147. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koua FHM, Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen JR. Structure of Sr-substituted photosystem II at 2.1 A resolution and its implications in the mechanism of water oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(10):3889–3894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219922110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cooper IB, Barry BA. Azide as a probe of proton transfer reactions in photosynthetic oxygen evolution. Biophys J. 2008;95(12):5843–5850. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.