Abstract

Objective

To assess the associations between diarrhoea and types of water sources, total quantity of water consumed and the quantity of improved water consumed in rapidly growing, highly populated urban areas in developing countries.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis using population-representative secondary data obtained from an interview survey conducted by the Asian Development Bank for the 2009 Kathmandu Valley Water Distribution, Sewerage and Urban Development Project.

Setting

Kathmandu Valley, Nepal.

Participants

2282 households.

Methods

A structured questionnaire was used to collect information from households on the quantity and sources of water consumed; health, socioeconomic and demographic status of households; drinking water treatment practices and toilet facilities.

Results

Family members of 179 households (7.8%) reported having developed diarrhoea during the previous month. For households in which family members consumed less than 100 L of water per capita per day (L/c/d), which is the minimum quantity recommended by WHO, the risk of contracting diarrhoea doubled (1.56-fold to 2.92-fold). In households that used alternative water sources (such as wells, stone spouts and springs) in addition to improved water (provided by a water management authority), the likelihood of contracting diarrhoea was 1.81-fold higher (95% CI 1.00 to 3.29) than in those that used only improved water. However, access to an improved water source was not associated with a lower risk of developing diarrhoea if optimal quantities of water were not consumed (ie, <100 L/c/d). These results were independent of socioeconomic and demographic variables, daily drinking water treatment practices, toilet facilities and residential areas.

Conclusions

Providing access to a sufficient quantity of water—regardless of the source—may be more important in preventing diarrhoea than supplying a limited quantity of improved water.

Keywords: Diarrhoeal Disease, Social Inequalities, Urbanisation, Water Supply, Nepal, Developing Countries

Article summary.

Article focus

The prevalence of diarrhoea remains high in many urban areas in developing countries, even though the provision of basic quantities of safe water has been achieved in line with the United Nation's Millennium Development Goals for water improvement.

This high prevalence could be because the minimal supply of improved water is not sufficiently effective in preventing water-borne diseases, particularly in rapidly developing, highly populated urban areas, such as Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. We evaluated the relationship between the quantity of accessible water, types of water sources and diarrhoea.

Key messages

Priority should be given to securing access to sufficient water—100 L/capita/day (L/c/d)—regardless of the source, rather than providing minimal access to improved water (20 L/c/d).

Based on our findings, the shortage of available surface and groundwater sources, which occurs in many highly populated cities worldwide, raises publichealth concerns.

Disadvantaged socieconomic status, particularly as reflected by poor education of the household head, was independently associated with a high likelihood of contracting diarrhoea.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study employed extensive population-representative data obtained through interviews using a structured questionnaire on water consumption, socioeconomic status and living conditions. The study aimed to measure water consumption as accurately as possible.

Information on developing diarrhoea in the previous month was self-reported and recalled, which may have resulted in a recall bias. Furthermore, this study was cross-sectional in design.

Introduction

Diarrhoeal diseases are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in less developed countries, particularly among young children.1–3 Currently, around 1.7 billion cases of diarrhoeal disease are reported every year,1 and approximately 1.5 million people have annually died worldwide because of diarrhoea, 80% of whom were in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.1 3

Improving water supply systems is essential in preventing diarrhoea.4–6 The United Nations set the objective of providing 73% coverage of access to improved water by 2015 as the 10th target of its Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).7 Although providing safe drinking water is critical, supplying sufficient quantities of water is equally necessary in maintaining a hygienic environment and good health.4 WHO has recommended a total consumption for all purposes of 100 L of water per capita per day (L/c/d).8 However, global trends in urbanisation and growing populations in large cities have posed new challenges for efforts to provide sufficient quantities of high-quality water.9 10 Moreover, socioeconomic and ethnic disparities with respect to water access have been exacerbated by the current trends of rapid urbanisation.9–11

Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, is typical of areas in developing countries where rapid urbanisation has occurred. The population of this valley increased from 1 645 091 in 2001 to 2 510 788 in 2011.12 In this valley, in 2003, 8.2% of the total outpatient department visits were by patients with diarrhoeal disease.13 In 2008, a national policy document14 stressed the importance of improving the health status of Nepal's urban population by providing a sustainable water supply and adequate sanitation. In the greater Kathmandu region, Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited (KUKL) is responsible for supplying improved water, and in 2010 KUKL covered 79% of the population in that region.15 Although this met MDGs for population coverage with safe water,16 the service provided by KUKL has not been formally assessed in terms of individual health. Evaluating the association between water sources, access to the amount of water and the possibility of developing diarrhoea, particularly diarrhoeal disease, is critical in planning future public-health interventions.14

The aims of this study were as follows: (1) to evaluate the impact of access to water in terms of quality (water provided by KUKL or obtained from alternative sources, such as wells, stone spouts and springs) and quantity (daily quantity available per capita) on the risk of diarrhoea; (2) to identify the quantity of improved (ie, KUKL-provided) or alternative water that is necessary to prevent diarrhoea. In addition, to identify vulnerable populations for access to water, we evaluated the association between socioeconomic status and diarrhoea.

Methods

Study area and participants

Data were extracted from the baseline survey of the Kathmandu Valley Water Distribution, Sewerage and Urban Development Project; the survey was conducted by Asian Development Bank (ADB) between August and September 2009. Kathmandu Valley comprises five municipalities and 114 village development committees (VDCs); municipalities are further divided into wards.17

We used a multistage cluster sampling method. Data collection involved two stages. In the first stage, 35 wards from the jurisdiction of the five municipalities and 15 VDCs were randomly selected. In the second stage, 84 geographical points were randomly selected from these municipalities and VDCs. Interviewers then visited the selected geographical points and interviewed family members residing in households located closest to those points. In all, 2282 households were included in this study. One person per household was interviewed using a structured questionnaire. No specific exclusion criteria were employed. Any type of household was selected, including both rented and owned residences. We excluded households in which, despite multiple visits, the members could not be contacted by the interviewers.

To ensure external validity, a reliable resident registry database should ideally be employed for survey sampling. However, in the ADB survey, the official resident registry database was not used to include members belonging to discriminated populations; such individuals are usually not legally registered. Approximately 20% of the households refused to participate in this survey. No data were available for comparing the characteristics of participants and non-participants. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the University of Yamanashi School of Medicine.

Measurements

Diarrhoea

In the present survey, diarrhoea was determined by asking the following question: ‘Did you or anyone in your family get sick last month? If yes, what was the illness?’ The answer to this question included the following 10 common ailments: fever, common cold, diarrhoeal disease, dengue fever, hepatitis, typhoid, malaria, skin disease, infected wounds and other illnesses. Households that selected the response for diarrhoeal disease were categorised as having had an occurrence of diarrhoea.

Water use

Variables related to water use included the type of water source, total quantity of water consumed and total quantity of improved (KUKL-provided) water consumed in a household. The type of water source was identified by asking the following question: ‘What water sources are currently used by your family?’ Respondents were allowed to select multiple water sources from among 15 options. Responses were categorised into the following groups: (1) improved sources only (treated water provided by KUKL); (2) alternative sources only (water obtained exclusively from dug wells, tube wells, stone spouts, springs, rivers, rainwater, jar water and tanker supply) and (3) combined water sources (both improved and alternative).

Water consumption was calculated by adding the values for the daily quantity of water consumed from all sources and dividing that figure by the number of family members in a household. Data were then classified into four groups (<20, 20−49, 50−99 and ≥100 L/c/d) based on the WHO definitions of per capita water requirements for domestic use.8 According to those definitions, 20 L/c/d is sufficient for consumption, though hygiene may be compromised (basic access); 50 L/c/d may meet the requirements for consumption, hygiene and laundry (intermediate access) and 100 L/c/d is sufficient for all purposes (optimal access).

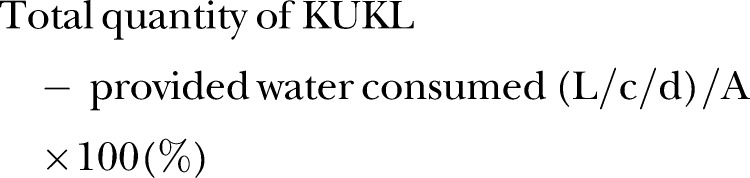

In this study, we defined ‘improved water’ as that provided by KUKL. The coverage of access to KUKL improved water against the quantities recommended by WHO was calculated using the following equation:

|

where A represents 20 L/c/d for basic access to improved water, 50 L/c/d for intermediate access or 100 L/c/d for optimal access. Households were subsequently categorised into the following groups based on coverage of access: fully covered (≥100%); partially covered (1−99%); and not covered (0%). This categorisation reflected access to improved water as recommended by WHO.

Covariates

We identified potential confounding factors with respect to both access to or use of water and the chances of developing diarrhoea: demographic variables, socioeconomic status, sanitary behaviour, toilet facilities and residential area. Although some factors were mildly correlated to one another, our preliminary analysis confirmed that the factors did not cause serious multicollinearity in multivariate analysis.

The demographic characteristics of the households evaluated included age of the household head, family size and number of individuals per room. Socioeconomic status included the following: ethnicity (Brahmin/Chhetri/Thakuri, Newar, Janajati or Dalit); occupation of the household head (white-collar occupation—service, business, house rental; blue-collar occupation—agriculture, manual labour or other; living from remittances; student; self-employed and other); monthly household income (<5000, 5000−15 000 or >15 000 Nepalese rupees) and highest educational level attained by the household head (no education/primary education; secondary education; or college graduate or higher). In Nepal, ethnicity is related to caste, and it exists in addition to traditional social class categories; some ethnicities, such as Dalit, are often disadvantaged in many aspects.18

Other variables included drinking water treatment practices (always treated, sometimes treated or never treated) and toilet facilities (water-sealed toilet or other: pit latrine, open space, no facilities or other). VDCs and municipality wards were also used as covariates because coverage of access to KUKL-provided water varied considerably across the residential areas.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate differences in the 1-month prevalence of diarrhoea at the household level (ie, the percentage of households reporting diarrhoea for the previous month), the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were used for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test and t test for continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression models were employed to adjust for potential confounding factors. Two models were used in the multivariate analysis. The first model was utilised to adjust for demographic and socioeconomic status, water treatment practices and toilet facilities. The second model was further adjusted for the fixed effect of residential area. We applied this two-step approach because, in our preliminary analysis, the impact of residential area on variations in the main fixed effect was relatively large. Moreover, although a residential area can strongly influence access to water, its impact may be concurrent with that of other variables, including socioeconomic status and sanitary environment; this is thus a potential cause of overadjustment. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences V.19 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

The average age of the household head was 47 years, and the median family size was four. The average age of the household head and family size were not associated with the likelihood of contracting diarrhoea among family members (p=0.97 and 0.27, respectively). Family members of 179 (7.8%) of the 2282 households studied developed diarrhoea. Regarding water sources, 26.2% of the households used KUKL-provided improved water only; 53.3% used both KUKL-provided and alternative water sources and 20.5% used alternative water sources only. With respect to the total quantity of water consumption, 14.2% of households consumed 100 L/c/d or more of water; 28.9% households consumed less than 20 L/c/d. Households with basic (≥20 L/c/d) and intermediate (≥50 L/c/d) access to KUKL-provided improved water accounted for 29.1% and 11.6%, respectively. Optimal access to improved water (≥100 L/c/d) was available to only 4% of households (table 1).

Table 1.

Household socioeconomic characteristics, types of water sources, access to improved water, sanitary behaviour and proportion of diarrhoea among family members during the previous month: the 2009 baseline survey of the Kathmandu Valley Water Distribution, Sewerage and Urban Development Project, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal

| Variable | Number of respondents, n (%) (total=2282) | Having diarrhoea, among family members n (%) (total=179) | p Value (χ2 test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water source for domestic use | |||

| Improved source only | 597 (26.2) | 42 (7.0) | 0.02 |

| Improved and alternative source | 1217 (53.3) | 112 (9.2) | |

| Alternative source only | 468 (20.5) | 25 (5.3) | |

| Total water consumption—litres/capita/day (L/c/d) | |||

| ≥100 | 305 (14.2) | 11 (3.6) | 0.002 |

| 50–99 | 431 (20.0) | 37 (8.6) | |

| 20–49 | 796 (36.9) | 58 (7.3) | |

| <20 | 623 (28.9) | 66 (10.9) | |

| Basic (≥20 L/c/d) access to improved water | |||

| Fully covered | 663 (29.1) | 44 (6.63) | 0.01 |

| Partially covered | 981 (43.1) | 96 (9.7) | |

| Not covered | 632 (27.8) | 39 (6.17) | |

| Intermediate (≥50 L/c/d) access to improved water | |||

| Fully covered | 264 (11.6) | 19 (7.1) | 0.12 |

| Partially covered | 1386 (60.7) | 121 (8.7) | |

| Not covered | 632 (27.7) | 39 (6.1) | |

| Optimal (≥100 L/c/d) access to improved water | |||

| Fully covered | 91 (4.0) | 4 (4.3) | 0.05 |

| Partially covered | 1553 (68.2) | 136 (8.7) | |

| Not covered | 632 (27.8) | 39 (6.1) | |

| Data missing | 121 (5.3) | 9 (7.4) | |

| Demographics | |||

| Number of individuals/room (median) | 1.3 | 0.01* | |

| Number of family members (median) | 4 | 0.27* | |

| Age of household head (mean) | 47 | 0.97† | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Occupation | |||

| White collar | 1771 (78.0) | 127 (7.1) | 0.06 |

| Blue collar | 217 (9.5) | 22 (10.1) | |

| Other | 283 (12.5) | 30 (10.6) | |

| Monthly household income—Nepalese rupees (NRs) | |||

| >15 000 | 740 (32.4) | 46 (6.2) | 0.21 |

| 5000–15 000 | 727 (31.9) | 59 (8.1) | |

| <5000 | 460 (20.2) | 42 (9.1) | |

| Data missing | 335 (15.6) | 32 (9.5) | |

| Level of education | |||

| College | 814 (35.7) | 48 (5.9) | 0.007‡ |

| Secondary (grades 4–10) | 795 (34.8) | 59 (7.4) | |

| No education/primary (grades 1–3) | 644 (28.2) | 69 (10.7) | |

| Data missing | 29 (1.3) | 3 (0.34) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Brahmin/Chettri/Thakuri | 956 (41.9) | 75 (7.8) | 0.95‡ |

| Newar | 711 (31.2) | 56 (7.9) | |

| Janajati | 469 (20.2) | 36 (7.7) | |

| Dalit | 25 (1.1) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Data missing | 121 (5.3) | 9 (7.4) | |

| Sanitary behaviour | |||

| Household treatment of drinking water | |||

| Always treated | 1513 (66.5) | 115 (7.6) | 0.67 |

| Sometimes treated | 101 (4.4) | 10 (9.9) | |

| Never treated | 663 (29.1) | 54 (8.1) | |

| Toilet facilities | |||

| Water-sealed toilet | 2145 (94.0) | 164 (7.6) | 0.14 |

| Other | 135 (6.0) | 15 (11.1) | |

*Mann-Whitney U test.

†Independent sample t test.

‡Fisher's exact test.

Univariate logistic analyses showed that households with access to less than 20 L/c/d of water had the highest likelihood of contracting diarrhoea: OR 3.16; 95% CI 1.64 to 6.08. Adjusting for sociodemographic and behavioural variables slightly attenuated this association: the adjusted OR was 2.53 (95% CI 1.10 to 6.33) for those with access to less than 20 L/c/d of water (model 2 in table 2).

Table 2.

ORs (95% CI) for having diarrhoea among family members according to the type of water source and total quantity of water consumed: results of logistic analysis, the 2009 baseline survey of the Kathmandu Valley Water Distribution, Sewerage and Urban Development Project, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1(−) | Model 2(+) | ||

| Water source | |||

| Improved source only | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Improved and alternative source | 1.33 (0.92 to 1.93) | 1.60 (0.95 to 2.69) | 1.81 (1.00 to 3.29) |

| Alternative source only | 0.74 (0.44 to 1.24) | 0.79 (0.38 to 1.63) | 0.95 (0.36 to 2.49) |

| Water consumption—litres/capita/day (L/c/d) | |||

| ≥100 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 50–99 | 2.51 (1.25 to 5.00) | 2.58 (1.07 to 6.23) | 2.92 (1.17 to 7.29) |

| 20–49 | 2.10 (1.08 to 4.05) | 1.52 (0.63 to 3.63) | 1.56 (0.63 to 3.85) |

| <20 | 3.16 (1.64 to 6.08) | 2.08 (0.85 to 5.05) | 2.53 (1.10 to 6.33) |

| Demographics | |||

| Number of individuals/room | 1.24 (1.09 to 1.41) | 1.06 (0.85 to 1.32) | 1.06 (0.84 to 1.33) |

| Number of family members | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.10) | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.24) |

| Age of household head | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Occupation | |||

| White collar | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Blue collar | 1.46 (0.90 to 2.35) | 1.06 (0.51 to 2.19) | 1.30 (0.59 to 2.89) |

| Other | 1.53 (1.01 to 2.33) | 1.26 (0.66 to 2.39) | 1.44 (0.72 to 2.88) |

| Monthly household income—Nepalese rupees (NRs) | |||

| >15 000 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5000–15 000 | 1.33 (0.89 to 1.98) | 0.88 (0.51 to 1.52) | 1.02 (0.56 to 1.84) |

| <5000 | 1.51 (0.98 to 2.34) | 1.13 (0.63 to 2.05) | 1.32 (0.70 to 2.47) |

| Data missing | 1.49 (0.93 to 2.39) | 1.21 (0.64 to 2.30) | 1.37 (0.69 to 2.71) |

| Education | |||

| College | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary (grades 4–10) | 1.27 (0.86 to 1.89) | 0.98 (0.57 to 1.70) | 1.07 (0.59 to 1.92) |

| No education/primary (grades 1–3) | 1.91 (1.30 to 2.81) | 1.85 (1.03 to 3.34) | 2.16 (1.13 to 4.11) |

| Data missing | 1.84 (0.53 to 6.30) | 1.24 (0.25 to 6.10) | 1.41 (0.28 to 7.59) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Brahmin/Chettri/Thakuri | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Newar | 1.00 (0.70 to 1.44) | 1.00 (0.60 to 1.69) | 1.03 (0.55 to 1.91) |

| Janajati | 0.97 (0.64 to 1.47) | 1.00 (0.55 to 1.82) | 0.98 (0.52 to 1.86) |

| Dalit | 1.60 (0.46 to 5.47) | 1.77 (0.44 to 7.16) | 1.46 (0.32 to 6.62) |

| Data missing | 0.94 (0.46 to 1.97) | 0.75 (0.25 to 2.26) | 0.62 (0.19 to 1.97) |

| Sanitary behaviour | |||

| Household treatment of drinking water | |||

| Always treated | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sometimes treated | 1.33 (0.67 to 2.63) | 1.23 (0.52 to 2.91) | 0.94 (0.37 to 2.33) |

| Never treated | 1.07 (0.77 to 1.51) | 0.73 (0.44 to 1.19) | 0.74 (0.43 to 1.29) |

| Toilet facilities | |||

| Water-sealed toilet | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 1.51 (0.86 to 2.64) | 1.55 (0.75 to 3.22) | 1.29 (0.57 to 2.93) |

(−)Not adjusted for dummy variables for wards in municipalities/village development committees (VDCs) and (+)adjusted for dummy variables for wards in municipalities/VDCs.

The OR of contracting diarrhoea among household members was 1.33 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.93) for households that used combined water sources, whereas the OR was 0.74 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.24) for those using only alternative water sources compared with those using only improved water sources. After accounting for variations in sociodemographic and behavioural variables, the adjusted OR for households using combined water sources was 1.81 (95% CI 1.00 to 3.89), whereas the adjusted OR for households using only alternative water sources was 0.95 (95% CI 0.36 to 2.49).

There was good evidence that disadvantaged socioeconomic conditions were associated with a high likelihood of developing diarrhoea. This association was most clearly evident for income level, highest educational level attained and Dalit ethnicity. Households with the lowest income were 1.32-fold more likely to contract diarrhoea (95% CI 0.70 to 2.47). Family members whose household head had completed only primary schooling or had no schooling were 2.16-fold more likely to develop diarrhoea (95% CI 1.13 to 4.11)—even after adjusting for multiple confounding factors, including other socioeconomic statuses (table 2). Among ethnic groups, the adjusted OR for contracting diarrhoea was highest for Dalits as compared with the Brahmins, the most advantaged caste group (adjusted OR, 1.46; 95% CI 0.32 to 6.62).

Table 3 shows ORs for diarrhoea based on the levels of coverage of access to improved water. ORs for contracting diarrhoea among households without optimal access to improved water tended to be higher than among those with full access (≥100 L/c/d); however, ORs were ≤1 when the association between improved water access and diarrhoea was tested using alternative thresholds (ie, 50 or 20 L/c/d).

Table 3.

ORs (95% CIs) of having diarrhoea among family members according to access to a quantity of improved water: results of logistic analysis, the 2009 baseline survey of the Kathmandu Valley Water Distribution, Sewerage and Urban Development Project, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1(−) | Model 2(+) | ||

| Basic access (20 L/c/d) to improved water source | |||

| Fully covered | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Partially covered | 1.52 (1.05 to 2.21) | 1.12 (0.69 to 1.82) | 1.09 (0.64 to 1.85) |

| Not covered | 0.92 (0.59 to 1.44) | 0.74 (0.41 to 1.33) | 0.83 (0.42 to 1.67) |

| Intermediate access (50 L/c/d) to improved water source | |||

| Fully covered | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Partially covered | 1.23 (0.74 to 2.03) | 0.71 (0.38 to 1.33) | 0.67 (0.34 to 1.31) |

| Not covered | 0.84 (0.48 to 1.49) | 0.51 (0.25 to 1.05) | 0.56 (0.25 to 1.28) |

| Optimal access (100 L/c/d) to improved water source | |||

| Fully covered | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Partially covered | 2.08 (0.75 to 5.77) | 1.82 (0.41 to 7.96) | 2.05 (0.45 to 9.31) |

| Not covered | 1.43 (0.49 to 4.10) | 1.22 (0.27 to 5.58) | 1.57 (0.32 to 7.61) |

Models 1 and 2 were adjusted for demographics, occupation, monthly household income, level of education, ethnicity, drinking water treatment and toilet facilities.

(−)Not adjusted for dummy variables for wards in municipalities/village development committees and (+)adjusted for dummy variables for wards in municipalities/village development committees.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that, although using alternative water sources in addition to improved water was associated with a higher risk of diarrhoea than using only improved water, limited access to water in terms of quantity (ie, less than the WHO-recommended optimal amount of 100 L/c/d)—regardless of the source—was strongly associated with developing diarrhoea. Disadvantaged socioeconomic status—particularly lower income level, poor educational level of the household heads and Dalit ethnicity—were also independently associated with a high likelihood of having diarrhoea. Based on these findings, priority should be given to securing access to sufficient quantities of water (≥100 L/c/d) rather than limited access to improved water.8 The lack of water impedes personal hygiene, such as washing, resulting in bacterial accumulation on the skin.4 19 20

Our findings demonstrate that households with partial access to improved water were at greater risk of diarrhoea than those with full access. There are two possible explanations for this result. First, in households with partial access to improved water, the supply may have been intermittent. In that situation, water contamination in the distribution network becomes more likely owing to absorption of outside contaminants as a result of low-pipe pressure.21 Second, residents in areas with intermittent access to improved water services may overestimate the reliability of the water and treat it inadequately. For example, having an intermittent water supply requires users to store water, which increases the risk of contamination.22–26

Those explanations may also account for the counterintuitive result of the present study, whereby households using only alternative water sources were not at increased risk of diarrhoea. Such households may have been more likely to treat their water before consumption and store it more carefully than other households. In addition, residents who were sceptical about the quality of the intermittently provided KUKL water may have selected alternative, better quality water sources when possible.

We found good evidence that socioeconomic status, particularly the level of education attained by the household head, was associated with diarrhoea risk among family members. The level of education attained may reflect health literacy (ie, competence in acquiring, understanding and using health information), which is important in maintaining a hygienic household environment and good health.27 28 In addition, although CIs were wide, the association between socioeconomic status and diarrhoea was also reflected in the high ORs for lower-income households, blue-collar workers and those of Dalit ethnicity—independent of their accessibility to improved water. These potential associations may reflect deprivation in terms of material goods and services other than water accessibility or psychosocial stress related to discrimination.17

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths. The survey was strictly controlled in terms of quality since it involved random sampling, rigorous measurement methods and private interviews.29 No other study in Nepal has formally evaluated the quantity of water consumed per household unit according to water source. Despite these advantages, some limitations should be noted. First, the onset of diarrhoea and other variables were self-reported, relying on the respondents’ perceptions of diarrhoeal symptoms. Information on diarrhoea was at the household level and did not account for household size. However, this impact may have been limited since we did not find any association between household size and the likelihood of contracting diarrhoea among family members. Moreover, one family member was asked to recall the incidences of diarrhoea among family members during the previous month. This may have resulted in a recall bias. For example, the occurrence of diarrhoeal episodes over the period of a month may have been under-reported since the family member questioned may have forgotten about them; this could have caused underestimation of the number of diarrhoeal events. Second, our estimates may have been biased owing to residual confounding of some unmeasured variables. For example, although we controlled for the fixed effects of residential areas, we did not know whether the area unit used was completely valid in capturing geographical variations in terms of the KUKL water supply, sociodemographic characteristics and culture or behaviour on water use. Thus, future studies should formally model such contextual effects.30 Third, although a response rate of 80% is not low, we were unable to evaluate whether the non-responding households were random. Accordingly, possible selection bias should be considered when interpreting the results of our study. Finally, we did not test the quality of the water that was used in each household. Further studies should evaluate the actual quality of water taken from various sources.

Conclusions

The results of this study have important implications for global health. Although most intervention programmes for diarrhoea prevention in urbanising areas of developing countries have focused on increasing the coverage of improved water sources and hygiene education, measures to increase access to sufficient quantities of water may be more important. In this study, only 14.2% of households consumed the optimal amount of water. Hence, in Kathmandu Valley, sustainable alternatives for securing sufficient water supply should be explored and promoted. Furthermore, when advancing these interventions, socioeconomic disparities in accessibility to safe water also have to be carefully considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Asian Development Bank for providing data for this analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS and YA conducted the analysis, participated in conceptualising the study and drafted the initial manuscript. KY collected data and drafted the manuscript. ZY and KN helped with study conceptualisation and manuscript drafting. NK conceived and conceptualised the study, supervised the analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was financially supported by the Global Centres of Excellence programme, University of Yamanashi, which is funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the University of Yamanashi School of Medicine.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Diarrhoeal disease. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs330/en/ (accessed 11 Apr 2013).

- 2.World Health Organization Water related disease, diarrhoea. http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/diseases/diarrhoea/en/index.html (accessed 11 Apr 2013).

- 3.Diarrhoea: why children are still dying and what can be done. Geneva: United Nations Children's Fund and World Health Organization, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esrey SA, Feachem RG, Hughes JM. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: improving water supplies and excreta disposal facilities. Bull World Health Organ 1985;63:757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis V, Cairncross S, Yonli R. Review: domestic hygiene and diarrhoea—pinpointing the problem. Trop Med Int Health 2000;5:22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majuru B, Mokoena M Michael, Jagals P, et al. Health impact of small-community water supply reliability. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2011;214:162–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millenium development goal, need assessment for Nepal 2010. Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal and United Nations Development Programme, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidelines for drinking water quality. 4th edn Geneva: World Health organization, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alirol E, Getaz L, Stoll B, et al. Urbanisation and infectious diseases in a globalised world. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:131–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Global water supply and sanitation assessment 2000 report. Geneva: World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban HEART, urban health equity assessment and response tool. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Planning Commission, Government of Nepal Preliminary results of National Population Census 2011. Kathmandu, Nepal: Central Bureau of Statistics, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 13.The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development Kathmandu valley environment outlook. Kathmandu, Nepal, The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Government of Nepal Nepal urban water supply and sanitation sector policy. Kathmandu, Nepal, Government of Nepal, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asian Development Bank Kathmandu Valley water supply and wastewater system improvement. Kathmandu, Nepal, Asian Development Bank, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kathmandu Upatyeka Khanepani Limited KUKL at a glance, third anniversary. Nepal, Kathmandu Upatyeka Khanepani Limited, 2010/2011 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Informal Sector Research and Study Center District development profile of Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal, Informal Sector Research and Study Center, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baniya J. Empowering Dalits in Nepal: lessons from South Korean NGO's strategies. Suwon, Korea: Ajou University, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langford RM. Hand washing and its impact in child health in Kathmandu, Nepal. [PhD thesis]. Durham University, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prasai T, Lekhak B, Joshi DR, et al. Microbiological analysis of drinking water of Kathmandu Valley. Sci World 2007;5:112–14 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuttle J, Ries AA, Chimba RM, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant epidemic Shigella dysenteriae type 1 in Zambia: modes of transmission. J Infect Dis 1995;171:371–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pradhan B. Assessing drinking water quality in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Health prospect new vision for new century. vol. 2, no. 2. Kathmandu: Nepal Public Health Society/Institute of Medicine, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clasen T, Bastable A. Faecal contamination of drinking water during collection and household storage: the need to extend protection to the point of use. J Water Health 2003;1:109–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maraj S, Rodda N, Jackson S, et al. Microbial deterioration of stored water for users supplied by stand-pipes and ground-tanks in a peri-urban community. Water SA 2009;32:693–9 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masangwi SJ, Morse TD, Ferguson NS, et al. Behavioural and environmental determinants of childhood diarrhoea in Chikwawa, Malawi. Desalination 2009;248:684–91 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishikawa H, Yano E. Patient health literacy and participation in the health-care process. Health Expect 2008;11:113–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald E, Bailie R, Brewster D, et al. Are hygiene and public health interventions likely to improve outcomes for Australian Aboriginal children living in remote communities? A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health 2008;8:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoden K. Kathmandu Valley water distribution, sewerage and urban development project: PPIAF-supported baseline survey Part I. Kathmandu, Nepal: Asian Development Bank, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subramanian SV. Multilevel methods in public health research. In: Kawachi I, , Berkman LF. eds. Neighborhood and health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001:65–111 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.