Abstract

Objectives

Timely delivery of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the treatment of choice for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Optimum delivery of PPCI requires an integrated network of hospitals, following a multidisciplinary, consultant-led, protocol-driven approach. We investigated whether such a strategy was effective in providing equally effective in-hospital and long-term outcomes for STEMI patients treated by PPCI within normal working hours compared with those treated out-of-hours (OOHs).

Design

Observational study.

Setting

Large PPCI centre in London.

Participants

3347 STEMI patients were treated with PPCI between 2004 and 2012. The follow-up median was 3.3 years (IQR: 1.2–4.6 years).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary endpoint was long-term major adverse cardiac events (MACE) with all-cause mortality a secondary endpoint.

Results

Of the 3347 STEMI patients, 1299 patients (38.8%) underwent PPCI during a weekday between 08:00 and 18:00 (routine-hours group) and 2048 (61.2%) underwent PPCI on a weekday between 18:00 and 08:00 or a weekend (OOHs group). There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups with comparable door-to-balloon times (in-hours (IHs) 67.8 min vs OOHs 69.6 min, p=0.709), call-to-balloon times (IHs 116.63 vs OOHs 127.15 min, p=0.60) and procedural success. In hospital mortality rates were comparable between the two groups (IHs 3.6% vs OOHs 3.2%) with timing of presentation not predictive of outcome (HR 1.25 (95% CI 0.74 to 2.11). Over the follow-up period there were no significant differences in rates of mortality (IHs 7.4% vs OFHs 7.2%, p=0.442) or MACE (IHs 15.4% vs OFHs 14.1%, p=0.192) between the two groups. After adjustment for confounding variables using multivariate analysis, timing of presentation was not an independent predictor of mortality (HR 1.04 95% CI 0.78 to 1.39).

Conclusions

This large registry study demonstrates that the delivery of PPCI with a multidisciplinary, consultant-led, protocol-driven approach provides safe and effective treatment for patients regardless of the time of presentation.

Article summary.

Article focus

Recent emerging evidence has suggested that patients admitted during the hospital out-of-hours (OOHs) have a higher mortality than those admitted during the normal working day. Whether this is true for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is unclear.

The optimum delivery of PPCI requires an integrated network of hospitals, following a multidisciplinary, consultant-led, protocol-driven approach. We investigated whether such a strategy was effective in providing equally effective in-hospital and long-term outcomes for STEMI patients treated by PPCI within normal working hours compared with those treated OOHs.

Key messages

A consultant-led protocol for provision of PPCI for treatment of STEMI is not associated with an increase in mortality for patients treated OOHs compared with in hours.

Delivery of primary PCI with a multidisciplinary, consultant-led, protocol-driven approach delivers safe and effective treatment for patients regardless of the time of presentation.

Similar strategies could be implemented for other acute medical conditions to improve outcomes ‘out of hours’ without involving complete replication of weekday hospital services at the weekend.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of this study is that it assesses outcome in a large contemporary cohort of consecutive patients undergoing PPCI for STEMI in a regional Heart Attack Centre, and therefore the results are likely to be widely generalisable. The large cohort also ensures that all-cause mortality can be used as the primary end point, which has the advantage of being entirely objective.

This study is a consecutive but retrospective observational analysis from a single centre's experience. We cannot account for the effects of residual confounding factors or selection bias that we have been unable to control for.

Background

There is increasing evidence suggesting that patients admitted during the weekend have a higher mortality than those admitted during the week.1 2 This excess mortality is thought to be strongly associated with the lack of cover of senior doctors (consultant level) during the weekends2 3 and has led to debate around redesigning healthcare provision to eliminate reduced staffing at the weekends.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the accepted gold standard for the treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) as recognised in all recent guidelines,4–6 and needs to be available at all hours (24/7). The delivery of PPCI services represents a significant logistical challenge, especially as many patients with STEMI present outside of usual hospital working hours (0800–1700) and at weekends. Whether patients with STEMI presenting outside of usual hospital working hours have inferior outcomes when compared with patients who present during the working day is still unclear.

Previous studies have demonstrated differing results in outcome after PPCI during ‘in-hours’ (IHs) compared with ‘out-of-hours’ (OOHs). Some studies showed no association with adverse outcomes and timing,7–14 whereas other studies suggested higher rates of mortality after PPCI during ‘out of hours’ compared with ‘in hours’.2 15–18 It is difficult to compare these studies directly because of differences in patient characteristics and variability in other treatment provided to patients—for example, some of these studies also used fibrinolysis.9 13 16 17 19

The aim of this study was therefore to compare the relative outcomes of patients with STEMI presenting to a UK regional PPCI centre outside of usual hospital working hours with patients presenting during usual working hours.

Methods

This was an observational cohort study of 3347 consecutive patients undergoing PPCI in a high volume centre between January 2004 and July 2012. These patients were divided into two groups based on the timing of PPCI (time taken as hospital arrival time). Those undergoing PPCI during usual hospital working hours, designated the ‘IH’ group (between 08:00 and 17:00 Monday to Friday), and those undergoing PPCI outside of usual hospital working hours, designated the ‘OOH’ group (ie, between 1701 and 0759 Monday to Friday and from 1701 Friday to 0759 Monday).

Service arrangement

The London Chest hospital is the tertiary heart attack centre for the North-East region of London and receives patients with STEMI for primary PCI in an unselected manner. This includes patients with cardiogenic shock and postcardiac arrest, including intubated and ventilated patients. The hospital serves a well-developed network of six local district general hospitals covering a population of 1.6 million people and includes close working with the London Ambulance Service. Patients are taken directly to the cardiac catheterisation laboratory 24 h a day with all cases performed by/under supervision of a consultant. OOHs, the catheterisation laboratory is covered by an ‘on-call team’. The on-call team is composed of an interventional cardiologist, a senior cardiology trainee, two cardiac catheterisation laboratory nurses, a cardiac physiologist and a radiographer. Aside from the senior cardiology trainee who is a resident in hospital OOHs, all the on-call team members are non-resident. OOHs, there are also reduced trainees covering the patients’ care postprocedure and other non-cardiac hospital services are also reduced with lower levels of staffing in radiology, pathology and anaesthetics (ITU) (all these services follow a similar consultant lead service OOHs).

PPCI pathway

During OOHs periods, the on-call team members are contacted immediately upon acceptance of a patient for PPCI. The on-call team members will be in the hospital within 40 min of the original call and the catheterisation laboratory will be ready to take the patient as soon as they arrive. In the majority of cases, the on-call team will be in the hospital before the arrival of the patient. During routine working hours, the on-call team is in the hospital and the catheterisation laboratories are functioning fully. Upon accepting a patient, the catheterisation laboratory coordinators inform the on-call interventional cardiologist and cardiology trainee and the next available free catheterisation laboratory is identified. The patient is taken to the catheterisation laboratory and PPCI is performed by the interventional cardiologist who is working in that laboratory. Standard PPCI protocol for our institution includes preloading with 300 mg aspirin, 300 or 600 mg clopidogrel and GPIIb/IIIA inhibitors unless contraindicated. Aspiration thrombectomy was performed at the operator's discretion.

Data were entered prospectively into the clinical database at the time of PPCI including patient characteristics, procedural factors and procedural complications. Successful primary PCI result was defined as final thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 3 and residual stenosis <30% in the infarct-related artery at the end of the procedure. Postdischarge complications and further revascularisation procedures were entered retrospectively from the electronic patient record and cardiac surgical database. Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE) were defined as death, recurrent myocardial infarction (defined as ‘new ischaemic pain with new ST elevation, or ischaemic ECG changes and a further elevation of enzymes (increase of creatine kinase-MB to ≥2 times the reference value or a rise in troponin T>30 ng/l (99th centile <10 ng/L)), whether treated with further revascularisation therapy or not’) and target vessel revascularisation. MACE events (identified from patient notes and electronic records) were adjudicated by three independent physicians who were not involved in the procedure and were unaware of the patient's PPCI timing (IHs vs OOHs). All-cause mortality was recorded up to 11 September 2012 from the UK Office of National Statistics. A retrospective data quality audit of 100 randomly selected medical records established that 94.8% of data fields, including complications, were entered correctly into the database.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD and categorical variables as absolute number and percentages. Normality of distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilkes test. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared with unpaired t tests, and non-normally distributed variables were compared with the Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ² test or Fisher's exact test when appropriate. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to represent survival and cumulative incidence of events over follow-up, with the log rank test used for evidence of a statistically significant difference between the groups. Time was measured from the first admission for a procedure to outcome (all-cause mortality). The association of timing of PPCI (OOH vs IH) with 30-day mortality was assessed using logistic regression analysis, and long-term mortality using Cox regression analyses. The proportional hazard assumption was satisfied for all outcomes evaluated. Finally, a non-parsimonious logistic regression model with procedural timing as the dependent variable was constructed incorporating all baseline clinical and procedural characteristics listed in tables 1 and 2 to generate a propensity score (ie, the predicted probability of procedural timing for each patient), which ranged between 0 and 1 for each patient. We subdivided our cohort into quintiles based on propensity score so that comparisons could be made between patients with similar baseline probabilities of mortality.20 The rates of 30-day and 5-year mortality in the IH vs OOH groups in each quintile were compared. Risk ratios (RRs) for mortality were calculated for each quintile, as well as an overall Mantel-Hantzel RR for the stratified analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics comparing IHs versus OOHs

| IHs (n=1299) | OOHs (n=2048) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 964 (74.2%) | 1579 (77.1%) | 0.051 |

| Age (years) | 64.02±14.2 | 63.16±14.3 | 0.126 |

| Hypertension | 509 (39.2%) | 784 (38.3%) | 0.344 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 225 (17.3%) | 362 (17.7%) | 0.424 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 401 (30.9%) | 608 (29.7%) | 0.253 |

| Smoking history | 722 (55.6%) | 1188 (58.0%) | 0.116 |

| Previous MI | 171 (13.2%) | 242 (11.8%) | 0.156 |

| Previous CABG | 34 (2.6%) | 53 (2.6%) | 0.539 |

| Previous PCI | 129 (9.9%) | 197 (9.6%) | 0.449 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 69 (5.3%) | 131 (6.4%) | 0.113 |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian) | 865 (66.6%) | 1319 (64.4%) | 0.226 |

| LVEF | 43.70±7.5 | 43.69±7.5 | 0.985 |

| CRF (eGFR <60) | 240 (18.5%) | 367 (17.9%) | 0.227 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CRF, chronic renal failure; MI,myocardial infarction; PCI,percutaneous coronary intervention; LVEF,left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 2.

Procedural characteristics comparing IHs versus OOHs (p<0.05)

| IHs (n=1299) | OOHs (n=2048) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral access | 779 (60.0%) | 1182 (57.7%) | 0.139 |

| Target vessel | |||

| Right coronary artery | 565 (43.5%) | 889 (43.4%) | 0.490 |

| Left main coronary artery | 9 (0.7%) | 14 (0.7%) | 0.585 |

| Left anterior descending (LAD) | 643 (49.5%) | 969 (47.3%) | 0.139 |

| Left circumflex coronary artery | 123 (9.5%) | 168 (8.2%) | 0.137 |

| Saphenous vein graft | 14 (1.1%) | 33 (1.6%) | 0.229 |

| Multivessel disease | 609 (46.9%) | 940 (45.9%) | 0.277 |

| Door-to-balloon time (median) | 30 IQR (18–70) | 38 IQR (21–76) | 0.709 |

| Door-to-balloon time >90 | 207 (15.9%) | 352 (17.2%) | 0.079 |

| Symptom-to-balloon time (median) | 176 IQR (117–328) | 195 IQR (125–330) | 0.562 |

| Call-to-balloon time (median) | 95 IQR (76–123) | 99 IQR (81–141) | 0.056 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 1061 (81.7%) | 1747 (85.3%) | 0.007 |

| Thrombectomy | 207 (15.9%) | 348 (17.0%) | 0.448 |

| Procedural success | 1095 (84.3%) | 886 (84.5%) | 0.530 |

IHs, in-hours; OOHs, out-of-hours.

Results

Within our study population of 3347 patients, 1299 (38.8%) PPCIs were performed IHs and 2048 (61.2%) PPCIs were performed OOHs.

Patient characteristics

Table 1 demonstrates the baseline characteristics between the two groups. There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the IHs group versus the OOHs group.

Procedural characteristics and outcomes

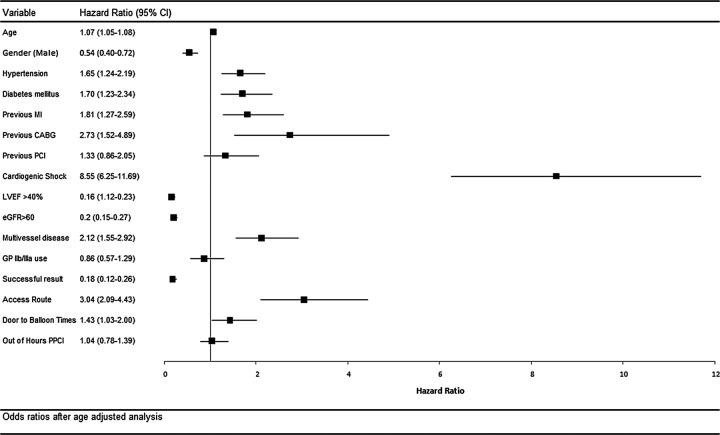

There was no difference in access route or target vessel intervention between the two groups. Although the Door-to-Balloon time was slightly longer in the OOHs group compared with the IHs group, this difference was not statistically significant (figure 1). In addition, there was no statistically significant difference in the Call-to-Balloon time between the two groups. There were higher rates of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use in the OOHs group compared with the IHs group. Procedural success rates and use of thrombectomy were similar between the two groups (table 2).

Figure 1.

Boxplots illustrating door-to-balloon times for primary percutaneous coronary intervention performed in-hours and out-of-hours. The median door-to-balloon time is indicated. The boundaries of the box plots refer to the 25th and 75th centiles, with the whisker bars representing the 5th and 95th centiles.

Early outcomes

There were no differences in the in-hospital MACE rates (IH 4.5% vs OOH 5.0%; p=0.644). There was no difference in either the 30-day MACE rates (IH 6.3% vs OOH 5.8%; p=0.580) or the 30-day mortality rates (IH 4.4% vs OOH 4.0%; p=0.613) between the groups (table 3).

Table 3.

In-hospital outcomes post PPCI comparing IHs versus OOHs

| IHs (n=1299) | OOHs (n=2048) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications bleeding complications | 48 (3.7%) | 61 (3.0%) | 0.165 |

| Haematoma | 9 (0.7%) | 8 (0.4%) | 0.274 |

| Blood transfusion | 30 (2.3%) | 33 (1.6%) | 0.140 |

| In-hospital MACE | |||

| Mortality | 42 (3.2%) | 74 (3.6%) | 0.321 |

| MI | 7 (0.6%) | 15 (0.7%) | 0.415 |

| CVA | 2 (0.2%) | 6 (0.2%) | 0.642 |

| Reintervention PCI | 11 (0.9%) | 10 (0.5%) | 0.170 |

| 30-day MACE | |||

| Mortality | 56 (4.3%) | 82 (4.0%) | 0.336 |

| MI | 26 (2.0%) | 27 (1.3%) | 0.207 |

| CVA | 3 (0.2%) | 6 (0.3%) | 0.446 |

| Re-intervention PCI | 17 (1.3%) | 6 (0.3%) | 0.088 |

CVA, cerebrovascular accident; IHs, in-hours; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; MI, myocardial infarction; OOHs, out-of-hours; PPCI,primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Predictors of early outcome

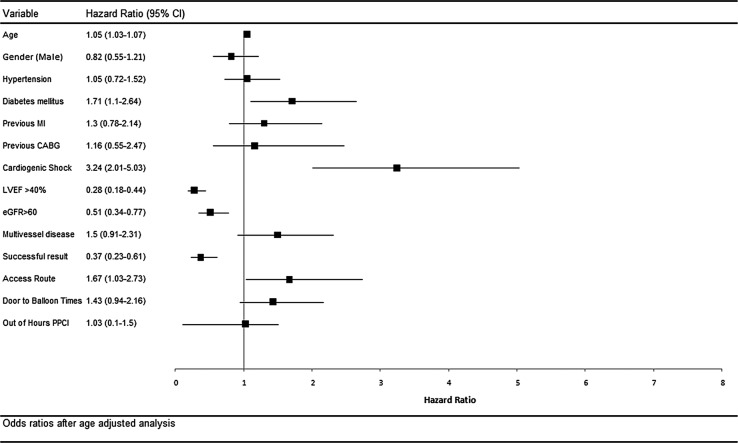

In terms of early (30 day) all-cause mortality and MACE events, OOHs PPCI was not an independent predictor of mortality (HR 0.74 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.29) and MACE events (HR 0.81 (95% CI 0.54 to 1.22). However, as expected, reduced renal function, shock, low ejection fraction and procedural success were independent predictors of early outcome (table 4).

Table 4.

Independent predictors of death, and major adverse cardiac events (reinfarction, death and unscheduled revascularisation) at log regression analyses

| Event | Variables | HR (95% CI) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | Age | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.07) | 0.001 |

| Shock | 5.60 (2.96 to 10.60) | <0.0001 | |

| eGFR>60 | 0.32 (0.18 to 0.58) | <0.0001 | |

| EF>40 | 0.18 (0.09 to 0.36) | <0.0001 | |

| Procedural success | 0.17 (0.09 to 0.32) | <0.0001 | |

| Multivessel disease | 1.92 (0.99 to 3.73) | 0.053 | |

| Out-of-hours | 0.74 (0.42 to 1.29) | 0.284 | |

| MACE | Age | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.05) | <0.0001 |

| Shock | 3.94 (2.30 to 6.74) | <0.0001 | |

| eGFR>60 | 0.44 (0.28 to 0.69) | <0.0001 | |

| EF>40 | 0.46 (0.30 to 0.71) | <0.0001 | |

| Procedural success | 0.26 (0.15 to 0.46) | <0.0001 | |

| Multivessel disease | 1.57 (1.31 to 1.90) | 0.003 | |

| Out-of–hours | 0.81 (0.54 to 1.22) | 0.316 |

EF, ejection fraction; eGFR epidermal growth factor receptor; MACE, major adverse cardiac events.

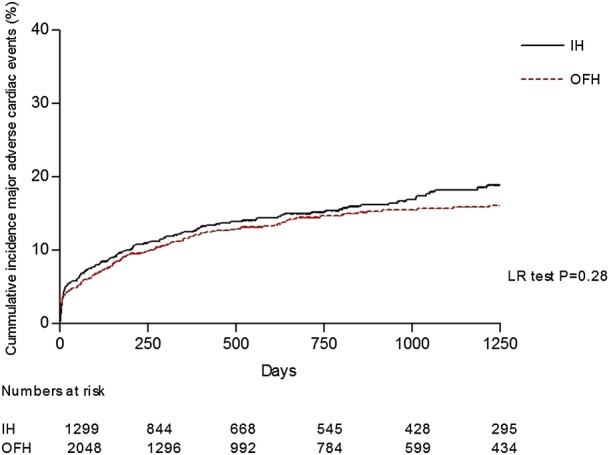

Long-term outcome

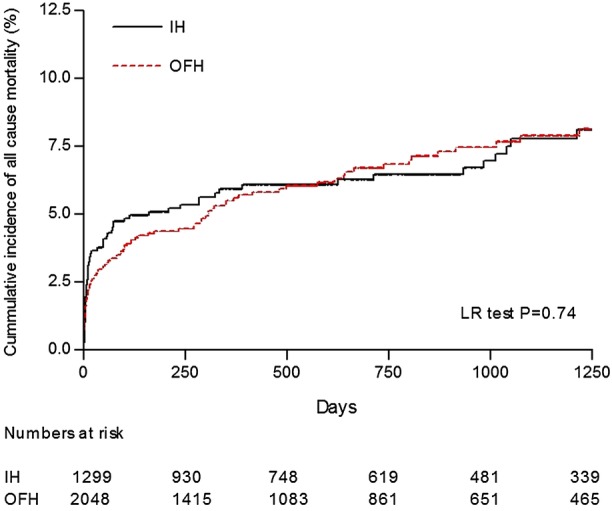

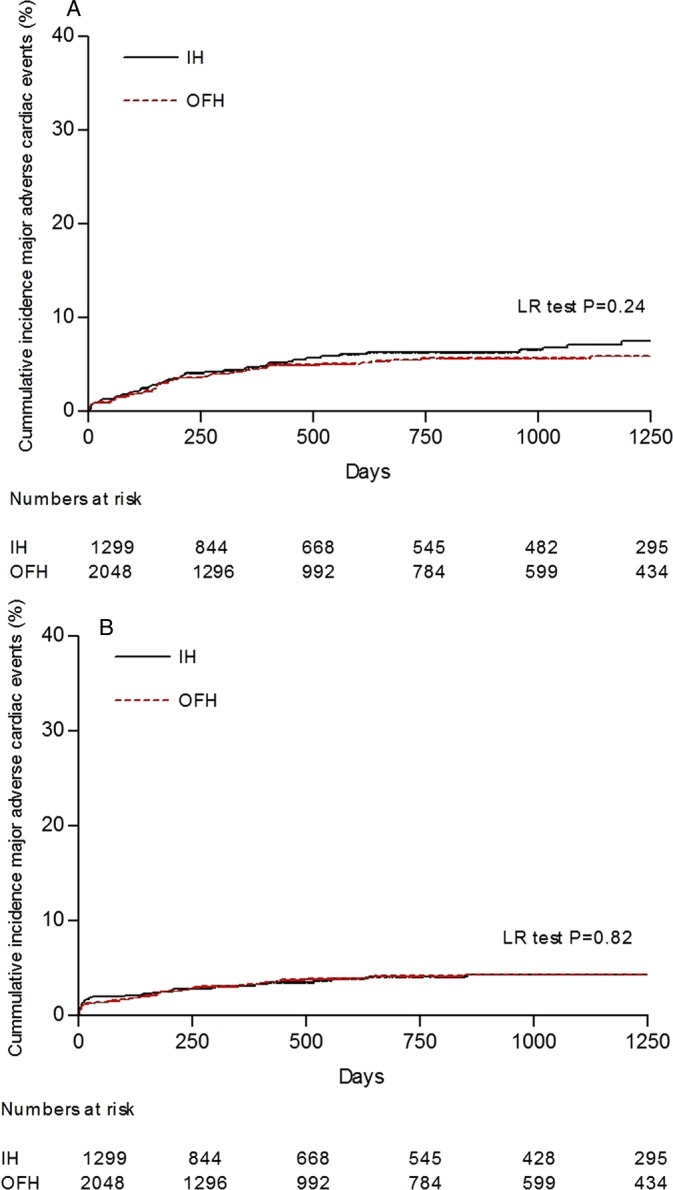

Patients were followed up for a median of 3 years (IQR 1.2–4.6 years). MACE event rates were not different between the groups at 1 year (IH 11.8% vs OOH 11.3%; p=0.757) or 3 years (14.2% vs 13.2%; p=0.489). Mortality rates at 1 year (IH 6.3% vs OOH 6.2%; p=0.934) and 3 years (OOH 7.1% vs 7.3%; p=0.938) were not different between the groups (figures 2–4).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing cumulative probability of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) after percutaneous coronary intervention comparing in-hours versus out-of-hours.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing cumulative probability of all-cause mortality after primary percutaneous coronary intervention comparing in-hours versus out-of-hours.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing cumulative incidence of (A) myocardial infarction and (B) target vessel revascularisation after primary percutaneous coronary intervention comparing in-hours versus out-of-hours.

Predictors of long-term outcome

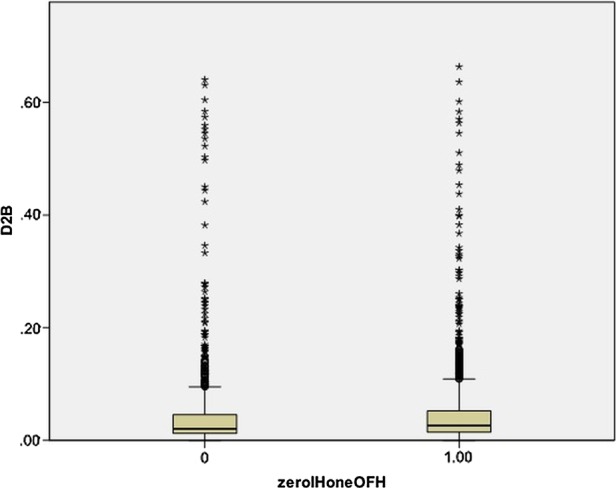

Timing of PPCI (OOHs vs IHs) was not a univariate predictor of all-cause mortality (unadjusted HR 1.04 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.39; figure 5). Incorporation of timing of PPCI into a multivariate Cox model did not change this (adjusted HR 1.03 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.50; figure 6). In addition, timing of PPCI was also not an independent predictor of MACE (unadjusted HR 0.93 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.14).

Figure 5.

Forest plot model of age-adjusted univariate analysis of predictors of mortality.

Figure 6.

Forest plot model of multivariate analysis of predictors of mortality.

Stratification of risk by propensity score (long-term outcome)

Analysis of patients stratified into quintiles using propensity score showed that higher risk patients were less likely to undergo PPCI OOHs (68.2% in Q1 vs 57.8% in Q5; table 5). There was no significant difference in long-term mortality between IH and OOH in any of the propensity score quintiles (Overall Mantel Haenszel HR 1.09 (0.77 to 1.55)).

Table 5.

Five-year mortality rates stratified by propensity score comparing patients treated IHs and OOHs with PPCI

| Quintile | OOHs procedures (%) | OOHs mortality rate (%) | IHs mortality rate (%) | Risk ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68.2 | 3.8 | 0.8 | 4.80 (0.61 to 37.94) |

| 2 | 64.5 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 0.82 (0.33 to 2.05) |

| 3 | 61.5 | 8.4 | 6.9 | 0.81 (0.38 to 1.71) |

| 4 | 57.5 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 1.02 (0.49 to 2.15) |

| 5 | 57.8 | 15.7 | 13.1 | 1.23 (0.70 to 2.18) |

| Overall mantel Haenszel RR | 1.09 (0.77 to 1.55) |

IHs, in-hours; OOHs, out-of-hours; PPCI,primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Discussion

We report both short-term and long-term outcomes after PPCI for STEMI in a large contemporary cohort of patients presenting in and out of usual hospital working hours at a regional UK heart attack centre. We have found that the timing of presentation to hospital does not affect mortality after STEMI. Importantly, there was no difference in effective treatment delivery as evidenced by door-to-balloon and call-to-balloon times between patients presenting IHs and those presenting OOHs. That rapid reperfusion can be achieved despite reduced staffing levels is likely to be the key to the equivalent outcomes of our OOH population.

It was first recognised in the 1970s that throughout the Western world mortality is up to 10% higher in patients admitted to acute hospitals at the weekend than during the week,7 21 with cardiovascular disease being one of the main causes of this excess mortality.21 In particular, there has been a focus on studies that have suggested increased mortality (due to delayed care) in patients with severe medical conditions who are admitted during weekends.7 Kostis et al16 also found higher mortality in patients with myocardial infarctions admitted on weekends.

Interest in patient management and safety outside normal working hours has increased recently following a report by Dr Foster Intelligence that showed increased mortality in UK hospitals at the weekend,22 and suggested a clear association between this excess and the reduced numbers of senior doctors in hospitals. Our study clearly shows that the availability of a consultant-led, protocol-driven service at all times of day abolishes the excess OOHs risk for myocardial infarction—one of the main causes of in-hospital mortality.

Hospital staffing is often reduced OOHs compared with normal working hours, which has been linked to increased mortality. In our study, despite the reduced staffing levels and support services at weekends, there was no excess in adverse outcomes, suggesting that suitable seniority and experience of the medical care on site is a crucial rather than an exact replication of weekday service provision. The clear consultant-led protocol that we adopt at our high volume institution is key to providing a standardised management strategy for patients, whether it is ‘in hours’ or ‘out of hours’. In our opinion, this system could be adapted to other acute medical emergencies such as upper gastrointestinal bleeds, diabetic ketoacidosis and acute cerebrovascular accidents, although we appreciate that the impact of a consultant-led protocol is likely to be different between procedure-based and non-procedure-based emergency therapies.

Providing a 24/7 service for PPCI is a challenge for both hospitals, medical personnel and the emergency medical services. Recent studies have found that up to two-third of STEMI patients are admitted to a PPCI centre outside normal working hours3—this was also the case for our series. A finding in the Dr Foster report22 was that the creation of networks through rationalisation of services in parts of the UK may improve outcomes at weekends, a strategy appropriate for a population such as London. Our study shows that the creation of one such network for Primary PCI in the North East of London is safe and leads to improved outcomes. Similar strategies could be implemented for other acute medical conditions to improve outcomes ‘out of hours’ without involving complete replication of weekday hospital services at the weekend.

Strengths and limitations of the current study

Our study is a consecutive but retrospective observational analysis from a single centre's experience. We cannot account for the effects of residual confounding or selection bias. The strength of this study is that it assesses outcome in a large contemporary cohort of consecutive patients undergoing PPCI for STEMI in a regional Heart Attack Centre. Therefore, the results are likely to be widely generalisable. The large cohort also ensures that all-cause mortality can be used as the primary end point. This has the advantage of being entirely objective. As this was an observational study, the findings may have been subject to confounding factors that we have been unable to control for. However, our dataset includes all major clinical variables known to affect outcome, which would support the validity of our results.

Conclusions

A consultant-led protocol for provision of PPCI for treatment of STEMI is not associated with an increase in mortality for patients treated OOHs compared with IHs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors listed in this manuscript fulfil all three of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines for authorship which are: substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. RKS and KCJ were responsible for coordinating the contribution of all authors to this paper. All authors made significant contributions to the development and conceptualisation of the manuscript. RKS, JDA, SG and BDI were responsible for drafting this paper. MW, ARA, AKJ, AM, AW and CK were responsible for editing and guidance on the paper. All authors were responsible for critically revising the paper. All authors approved the final version of this paper for submission.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The data were collected as part of a mandatory national cardiac audit and all patient identifiable fields were removed prior to analysis. The local ethics committee advised us that formal ethical approval was not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Freemantle N, Richardson M, Wood J, et al. Weekend hospitalization and additional risk of death: an analysis of inpatient data. J R Soc Med 2012;105:74–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cubeddu RJ, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Kiernan TJ, et al. ST-elevation myocardial infarction mortality in a major academic center “on-” versus “off-“ hours. J Invasive Cardiol 2009;21:518–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noman A, Ahmed JM, Spyridopoulos I, et al. Mortality outcome of out-of-hours primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the current era. Eur Heart J 2012;33:3046–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction–executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). (1524–4539 (Electronic))

- 5. Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), Steg PG, James SK, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.NICE Myocardial infarction with ST-segment-elevation (STEMI). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med 2001;345:663–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casella G, Ottani F, Ortolani P, et al. Off-hour primary percutaneous coronary angioplasty does not affect outcome of patients with ST-Segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treated within a regional network for reperfusion: the REAL (Registro Regionale Angioplastiche dell'Emilia-Romagna) registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:270–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zahn R, Schiele R, Seidl K, et al. Daytime and nighttime differences in patterns of performance of primary angioplasty in the treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Maximal Individual Therapy in Acute Myocardial Infarction (MITRA) Study Group. Am Heart J 1999;138(6 Pt 1):1111–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadeghi HM, Grines CL, Chandra HR, et al. Magnitude and impact of treatment delays on weeknights and weekends in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction (the cadillac trial). Am J Cardiol 2004;94:637–40, A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortolani P, Marzocchi A, Marrozzini C, et al. Clinical comparison of “normal-hours” vs “off-hours” percutaneous coronary interventions for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2007;154:366–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger A, Meier JM, Wasserfallen JB, et al. Out of hours percutaneous coronary interventions in acute coronary syndromes: long-term outcome. Heart 2006;92:1157–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, et al. Impact of time of presentation on the care and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2008;117:2502–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cubeddu RJ, Palacios IF, Blankenship JC, et al. Outcome of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention during on- versus off-hours (a Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction [HORIZONS-AMI] trial substudy). Am J Cardiol 2013;111:946–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henriques JP, Haasdijk AP, Zijlstra F. Outcome of primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction during routine duty hours versus during off-hours. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:2138–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, et al. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1099–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magid DJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Relationship between time of day, day of week, timeliness of reperfusion, and in-hospital mortality for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA 2005;294:803–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saleem MA, Kannam H, Aronow WS, et al. The effects of off-normal hours, age, and gender for coronary angioplasty on hospital mortality in patients undergoing coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:763–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003;361:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenbaum PR, Paul R, Rubin DB, et al. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc 1984;79:516–24 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogot E, Fabsitz R, Feinleib M. Daily variation in USA mortality. Am J Epidemiol 1976;103:198–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goddard AF, Lees P. Higher senior staffing levels at weekends and reduced mortality. BMJ 2012;344:e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.