Abstract

Objectives

While multiple studies have demonstrated variations in the quality of cancer care in the USA, payers are increasingly assessing structure-level and process-level measures to promote quality improvement. Hospital-acquired adverse events are one such measure and we examine their national trends after major cancer surgery.

Design

Retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of a weighted-national estimate from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) undergoing major oncological procedures (colectomy, cystectomy, oesophagectomy, gastrectomy, hysterectomy, lung resection, pancreatectomy and prostatectomy). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs) were utilised to identify trends in hospital-acquired adverse events.

Setting

Secondary and tertiary care, US hospitals in NIS

Participants

A weighted-national estimate of 2 508 917 patients (>18 years, 1999–2009) from NIS.

Primary outcome measures

Hospital-acquired adverse events.

Results

324 852 patients experienced ≥1-PSI event (12.9%). Patients with ≥1-PSI experienced higher rates of in-hospital mortality (OR 19.38, 95% CI 18.44 to 20.37), prolonged length of stay (OR 4.43, 95% CI 4.31 to 4.54) and excessive hospital-charges (OR 5.21, 95% CI 5.10 to 5.32). Patients treated at lower volume hospitals experienced both higher PSI events and failure-to-rescue rates. While a steady increase in the frequency of PSI events after major cancer surgery has occurred over the last 10 years (estimated annual % change (EAPC): 3.5%, p<0.001), a concomitant decrease in failure-to-rescue rates (EAPC −3.01%) and overall mortality (EAPC −2.30%) was noted (all p<0.001).

Conclusions

Over the past decade, there has been a substantial increase in the national frequency of potentially avoidable adverse events after major cancer surgery, with a detrimental effect on numerous outcome-level measures. However, there was a concomitant reduction in failure-to-rescue rates and overall mortality rates. Policy changes to improve the increasing burden of specific adverse events, such as postoperative sepsis, pressure ulcers and respiratory failure, are required.

Keywords: Patient Safety Indicators, Cancer surgery, Preventable Adverse Events, Patient Safety Indicators, Quality Improvement

Article summary.

Article focus

Variations in the quality of surgical oncology care in the USA remain unclear.

Payers are increasingly assessing the structure-level and process-level measures to promote quality improvement.

Hospital-acquired adverse events are one such measure and we examine their national trends after major cancer surgery.

Key messages

Over the past decade, there has been a substantial increase in the national frequency of potentially avoidable adverse events after major cancer surgery, but there was also a concomitant reduction in the failure-to-rescue rates and overall mortality rates.

Patients treated at lower volume hospitals experienced both a higher frequency of potentially avoidable adverse events and failure-to-rescue rates.

Policy changes to improve the increasing burden of specific adverse events, such as postoperative sepsis, pressure ulcers and respiratory failure, are required.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the largest study to assess the quality of oncological surgical care in a nationally representative cohort of US patients.

Validated Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs) were utilised to identify trends in hospital-acquired adverse events.

Inherent to the retrospective analyses of large administrative datasets, this study is limited by potential biases due to the case-mix and miscoding.

While PSIs have been shown to perform well as screening tools from an epidemiological perspective (overidentification and few false-negatives), concerns related to high false-positive rates exist.

Introduction

There has been much interest in assessing the downstream effects and complexities of the contemporary delivery of healthcare. However, observational studies examining preventable adverse events are confounded by the loss of information when administrative data are abstracted from patient records. Recently, several initiatives have been directed to improve consistency, relevance and fidelity in the process of transforming clinical data into administrative datasets and subsequent practice-changing results. Following a landmark study by Iezzoni et al1 on computerised algorithms to identify quality-of-care disparities in administrative datasets, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed a standardised system for accrual and reporting of unintended hospital-acquired adverse events, termed patient safety indicators (PSIs).2 Subsequently, Zhan and Miller3 examined the relationship between multiple process-level, setting-level and outcome-level measures and adverse events identified using the AHRQ's PSI system, and reported substantial but variable effects on the healthcare system.

Nonetheless, there is a paucity of studies evaluating the burden of preventable adverse events4 and this is particularly true for major surgical oncology care in the USA. Multiple studies have demonstrated that significant variation exists in cancer incidence rates5 and in access to quality cancer care,6 7 but variations in the actual quality of surgical oncology care remain unclear.

Hence, we undertook a national assessment of the quality of major surgical oncology care within a standardised framework of preventable adverse events to examine trends in patient safety within the USA. We also evaluated the prevailing hypothesis8–10 explaining the volume–complication–mortality relationship, which states that higher mortality rates for patients undergoing surgery at low-volume hospitals are preferentially explained by higher failure-to-rescue rates (ie, mortality after a hospital-acquired adverse event), rather than a higher incidence of such adverse events in the first place.

Methods

Data source

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) consists of an array of longitudinal hospital inpatients datasets as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. It was established by AHRQ and functions through a Federal-state affiliation. It is the largest publicly accessible all-payer inpatient database.11 The database consists of discharge information from eight million inpatient visits and patients covered by multiple insurance types (including Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance and uninsured patients) are represented.

Study cohort

We relied on hospital discharges for patients undergoing one of eight major cancer surgeries in the USA between 1999 and 2009. The major oncological surgeries consisted of colectomy, cystectomy, oesophagectomy, gastrectomy, hysterectomy, pneumonectomy/lobectomy, pancreatectomy and prostatectomy. Oncological indications were selected based on International Classification of Diseases-9 (ICD-9) clinical modification diagnostic codes. These particular procedures were chosen based on procedure volume and care was taken to include cancer surgeries involving different organ systems across a range of surgical specialties.

Patient and hospital information

Patient characteristics evaluated included age at inpatient hospitalisation, race, gender, insurance characteristics and comorbidities. Regarding race, patients were classified as White, Black, Hispanic and Other (Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American). Regarding insurance characteristics, patients were categorised based on the primary payer: Medicare, Medicaid, Private insurance (Blue Cross, commercial carriers, private HMO's and PPO's) and other insurance types (including uninsured patients). Charlson Comorbidity index (CCI) was derived according to Charlson et al,12 and adapted according to the previously defined methodology of Deyo et al.13 Median household income of the patient's ZIP code of residence, as derived from the US Census, was used to define socioeconomic status and patients were divided into quartiles:<$25 000, $25 000–$34 999, $35 000–$44 999 and ≥$45 000. Hospital information examined included hospital location (urban vs rural) and region (Northeast, Midwest, South and West), as defined by the USA Census Bureau14 and academic teaching status as derived from the AHA Annual Survey of Hospitals. Hospital volume was categorised into volume quartiles as described previously.15

Primary outcomes

The AHRQ PSIs were used to identify potentially preventable hospital-acquired adverse events. For the PSI project, AHRQ commissioned experts from the Evidence-based Practice Center at the University of California San Francisco and Stanford University and from the University of California Davis to evaluate the existing literature and help develop an evidence-based approach for improving patient safety.2 The objective of this project was to facilitate the identification, quantification and reporting of preventable hospital-acquired adverse events from routinely collected administrative information. The process of identification of PSI included initial literature analysis of previously reported patient safety problems, organised peer review of chosen PSIs, structured review of ICD-9 codes for each PSI and, finally, empirical analysis of each PSI and feedback from multidisciplinary teams (physicians and specialists, nurses, pharmacists and coding and experts).2 The complete set of PSIs utilised is displayed in the appendix and is available on the AHRQ website.16 The list includes various preventable adverse events that have been shown to have reasonable accuracy and validity as indicators for enhancing quality improvement and patient safety.

Statistical analysis

Proportions, frequencies, means, medians, SD and IQRs were obtained for each variable. National trends in the frequency of PSI events, failure to rescue (defined as mortality after a PSI event), and in-hospital mortality were also analysed as the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC), based on the linear regression methodology described by Anderson et al.17 Logistic regression models were used to examine predictors of PSI events, and to examine the effect of PSI events on multiple outcomes-level measures, including in-hospital mortality, excessive charges (≥75th centile of inflation-adjusted charges for each individual procedure) and prolonged length of stay (≥75th centile of each individual procedure). Subsequently, we examined the volume–complication–mortality relationship in overall and procedure-specific analyses to study the relationship between mortality at low-volume hospitals and failure-to-rescue rates. Generalised estimating equations were used in each multivariable analysis to adjust for clustering among hospitals.18 All analyses were two-sided, and significance was defined as p<0.05 and performed using the R statistical package (R foundation for Statistical Computing, V.2.15.1).

Results

The baseline demographic characteristics of our cohort of patients >18 years old undergoing one of eight major cancer procedures in the USA between 1999 and 2009 (n=2 508 917) are shown in table 1. A weighted estimate of 324 852 patients experienced ≥1-PSI event (12.9%). Patients with ≥1-PSI event were more likely to be older, be women, have higher CCI, participate in Medicare, have lower socioeconomic status, and be treated at lower volume non-academic hospitals when compared with patients who did not experience any hospital-acquired preventable adverse events.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients >18 years undergoing major cancer surgery, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1999–2009

| Variables | Baseline characteristics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (%) | Without PSI event (%) | With PSI event (%) | p Value | |

| Weighted number of patients | 2 508 917 | 2 184 065 (87.1) | 324 852 (12.9) | – |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 65.9 (11.7) | 65.4 (11.6) | 69.5 (11.7) | <0.001† |

| Median (IQR) | 66 (5874) | 65 (5773) | 71 (6278) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 511 361 (60.3) | 1 331 716 (61.1) | 179 645 (55.3) | <0.001* |

| Female | 993 704 (39.7) | 848 527 (38.9) | 145 177 (44.7) | |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 1 525 021 (60.8) | 1 324 373 (60.6) | 200 648 (61.8) | <0.001* |

| Black | 177 986 (7.1) | 154 028 (7.1) | 23 958 (7.4) | |

| Hispanic | 98 532 (3.9) | 86 128 (3.9) | 12 404 (3.8) | |

| Other | 93 041 (3.7) | 81 492 (3.6) | 11 549 (3.6) | |

| Unknown | 614 337 (24.5) | 76 293 (23.5) | 76 293 (23.5) | |

| CCI | ||||

| 0 | 1 566 723 (62.4) | 1 412 545 (64.7) | 154 178 (47.5) | <0.001* |

| 1 | 623 985 (24.9) | 516 640 (23.7) | 107 345 (33.0) | |

| 2 | 127 538 (5.1) | 102 276 (4.7) | 25 262 (7.8) | |

| ≥3 | 190 670 (7.6) | 152 603 (7.0) | 38 067 (11.7) | |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Private | 1 057 919 (42.2) | 968 015 (44.3) | 89 904 (27.7) | <0.001* |

| Medicaid | 80 666 (3.2) | 66 947 (3.1) | 13 719 (4.2) | |

| Medicare | 1 265 920 (50.5) | 1 056 618 (48.4) | 209 302 (64.4) | |

| Other | 104 412 (4.2) | 92 485 (4.2) | 11 927 (3.7) | |

| Median household income by ZIP code | ||||

| 1–24 999 | 369 796 (14.7) | 313 652 (14.4) | 56 144 (17.3) | <0.001* |

| 25 000–34 999 | 596 202 (23.8) | 513 758 (23.5) | 82 444 (25.4) | |

| 35 000–44 999 | 646 869 (25.8) | 563 398 (25.8) | 83 471 (25.7) | |

| 45 000+ | 842 375 (33.6) | 746 499 (34.2) | 95 876 (29.5) | |

| Unknown | 53 672 (2.1) | 46 757 (2.1) | 6915 (2.1) | |

| Annual hospital volume | ||||

| 1st quartile | 591 675 (23.6) | 510 024 (23.4) | 81 651 (25.1) | <0.001* |

| 2nd quartile | 640 229 (25.5) | 551 980 (25.3) | 88 249 (27.2) | |

| 3rd quartile | 636 482 (25.4) | 554 325 (25.4) | 82 157 (25.3) | |

| 4th quartile | 640 531 (25.5) | 567 737 (26.0) | 72 794 (22.4) | |

| Hospital location | ||||

| Rural | 268 349 (10.7) | 235 606 (10.8) | 32 743 (10.1) | <0.001* |

| Urban | 2 239 651 (89.3) | 1 947 705 (89.2) | 291 946 (89.9) | |

| Hospital region | ||||

| Northeast | 526 593 (21.) | 458 684 (21.0) | 67 909 (20.9) | <0.001* |

| Midwest | 608 988 (24.3) | 532 951 (24.4) | 76 037 (23.4) | |

| South | 8 822 566 (35.2) | 762 212 (34.9) | 120 354 (37.0) | |

| West | 490 770 (19.6) | 430 218 (19.7) | 60 552 (18.6) | |

| Hospital teaching status | ||||

| Non-teaching | 1 135 065 (45.3) | 979 636 (44.9) | 155 429 (47.9) | <0.001* |

| Teaching | 1 372 935 (54.7) | 1 203 675 (55.1) | 169 260 (52.1) | |

*A chi-square test was performed.

†A Mann-Whitney test was performed.

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity index; PSI, Patient Safety Indicator.

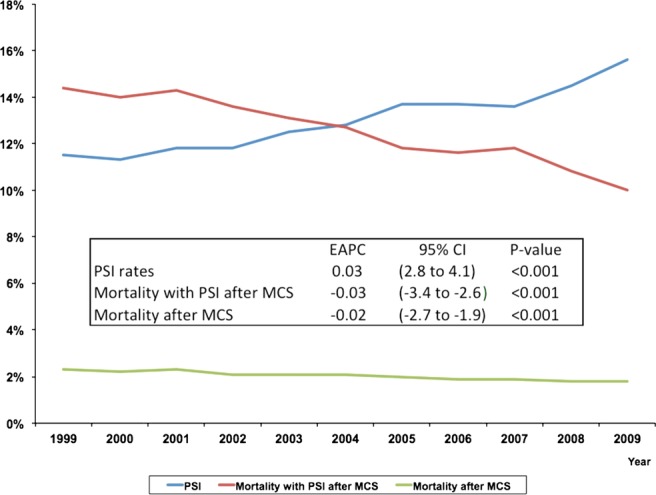

The national trends in PSI rates, overall mortality rates and failure-to-rescue rates in patients undergoing major cancer surgery in the USA are depicted in figure 1. While a steady increase in the frequency of PSI-events after major cancer surgery has occurred over the last 10 years (EAPC 3.5%; 95% CI 2.8% to 4.1%; p<0.001), a concomitant decrease in failure-to-rescue rates (EAPC −3%; 95% CI −3.4% to −2.6%; p<0.001) and overall mortality (EAPC −2.3%; 95% CI −2.7% to −1.9%; p<0.001) was noted.

Figure 1.

National trends in Patient Safety Indicator (PSI) rates, overall mortality rates and failure-to-rescue rates in patients undergoing major cancer surgery (MCS) in the USA (1999–2009); EAPC-estimated annual percentage change.

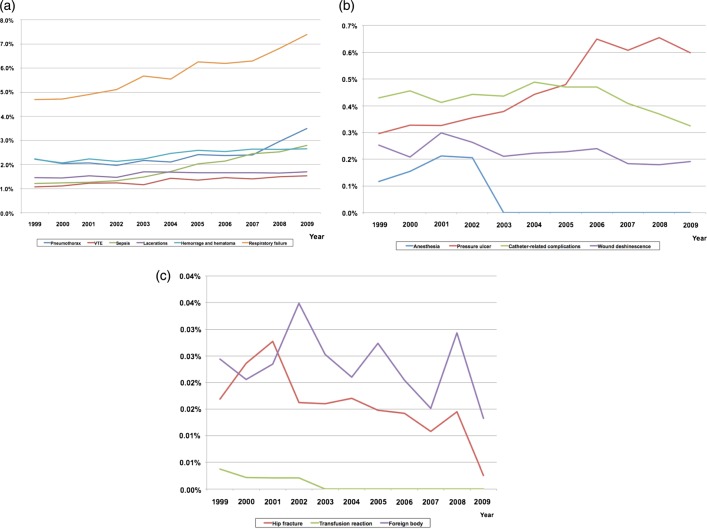

While there was a significant increase in overall PSI event rates over the course of the study, substantial heterogeneity was noted in terms of individual PSIs (figure 2A–C). Substantial increases were noted in the annual incidence of postoperative sepsis (EAPC 14.1%, 95% CI 12.0% to 16.2%; p<0.001), pressure ulcer (EAPC 13.4%, 95% CI 10.2% to 16.6%; p<0.001) and respiratory failure (EAPC 5.6%, 95% CI 4.8% to 6.4%; p<0.001), while significant advances were made in the prevention of anaesthetic complications (EAPC −17.5%, 95% CI −27.6% to −7.5%; p=0.008), hip fractures (EAPC −8.9%, 95% CI −13.6% to −4.3%; p=0.005) and transfusion reactions (EAPC −7.9%, 95% CI −13.1% to −2.8%; p=0.001) in the perioperative period.

Figure 2.

(A–C) National trends in individual Patient Safety Indicators over the study period (1999–2009) in patients undergoing major cancer surgery (MCS) in the USA.

Results of a multivariable logistic regression model predicting the odds of ≥1-PSI event after major cancer surgery are shown in table 2. These factors included: female gender (vs male, OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.90; p<0.001), Black race (vs Caucasians OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.21; p<0.001), higher CCI (≥3 vs 0, OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.34 to 1.42; p<0.001), Medicaid (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.39 to 1.52) and Medicare insurance (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.19; p<0.001), lower median household income (4th quartile vs 1st quartile, OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.89 to 0.95; p<0.001) and surgeries at lower volume hospitals (4th quartile vs 1st quartile, OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.78; p<0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression predicting occurrence of at least one patient safety indicator event

| Multivariable predictors of ≥1 PSI event* |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Weighted number of patients | ||

| Age (years) | 1.018 (1.017 to 1.019) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| Female | 0.878 (0.862 to 0.895) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| Black | 1.172 (1.132 to 1.213) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.973 (0.930 to 1.019) | 0.245 |

| Other | 0.938 (0.895 to 0.983) | 0.008 |

| Unknown | 1.010 (0.988 to 1.033) | 0.366 |

| CCI | ||

| 0 | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 1 | 1.227 (1.203 to 1.252) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1.188 (1.147 to 1.230) | <0.001 |

| ≥3 | 1.377 (1.336 to 1.419) | <0.001 |

| Insurance status | ||

| Private | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| Medicaid | 1.454 (1.388 to 1.523) | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 1.155 (1.127 to 1.185) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.127 (1.075 to 1.181) | <0.001 |

| Median household income by ZIP code | ||

| 1–24 999 | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 25 000–34 999 | 0.986 (0.959 to 1.013) | 0.305 |

| 35 000–44 999 | 0.960 (0.934 to 0.987) | 0.004 |

| 45 000+ | 0.920 (0.894 to 0.946) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.003 (0.943 to 1.067) | 0.929 |

| Annual hospital volume | ||

| 1st quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd quartile | 0.945 (0.922 to 0.969) | <0.001 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.883 (0.860 to 0.907) | <0.001 |

| 4th quartile | 0.761 (0.739 to 0.783) | <0.001 |

| Hospital location | ||

| Rural | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| Urban | 1.236 (1.198 to 1.275) | <0.001 |

| Hospital region | ||

| Northeast | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| Midwest | 0.991 (0.964 to 1.019) | 0.541 |

| South | 1.049 (1.024 to 1.075) | <0.001 |

| West | 1.018 (0.989 to 1.047) | 0.229 |

| Hospital teaching status | ||

| Non-teaching | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| Teaching | 0.972 (0.952 to 0.992) | 0.007 |

*Other predictors included procedure type (colectomy-ref; cystectomy (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.45 to 1.57), oesophagectomy (OR 5.16, 95% CI 4.81 to 5.54), gastrectomy (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.93 to 2.09), hysterectomy (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.58), lung resection (OR 2.44, 95% CI 2.39 to 2.50), pancreatectomy (OR 1.79, 95% CI 1.71 to 1.88), prostatectomy (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.27)) and year of surgery (OR 1.037, 95% CI 1.034 to 1.040). All p<0.001.

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity index; PSI, Patient Safety Indicator.

The occurrence of ≥1-PSI event had significant multivariable effects on specific outcome-level measures after major cancer surgery (table 3). Patients who suffered from ≥1-PSI event experienced higher rates of in-hospital mortality (OR 19.38, 95% CI 18.44 to 20.37), prolonged length of stay (OR 4.43, 95% CI 4.31 to 4.54) and excessive hospital charges (OR 5.21, 95% CI 5.10 to 5.32).

Table 3.

Multivariable effects of ≥1 patient safety indicator events on in-hospital mortality, prolonged length of stay and excessive hospital charges in patients undergoing major cancer surgery in the USA between 1999 and 2009

| ≥1 Patient safety indicator vs no PSI |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI)* | p Value |

| In-hospital mortality (n=51 312)† | 19.380 (18.439 to 20.368) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged length of stay (n=888 220) | 4.426 (4.313 to 4.542) | <0.001 |

| Excessive hospital charges (n=609 128) | 5.207 (5.097 to 5.319) | <0.001 |

*Each of these effects was derived from individual multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for hospital clustering, procedure type, age, gender, race, Charlson comorbidity index, insurance status, socioeconomic status, year of admission, hospital location, hospital region, hospital volume quartiles and institutional academic status.

†1457 Patients with missing in-hospital mortality data.

We also assessed the effect of hospital volume on the incidence of PSIs and failure to rescue (table 4). In the overall analysis of patients undergoing any of the eight procedures, very high-volume hospitals (4th quartile) had both a lower PSI event rate and lower failure-to-rescue rates. However, this relationship was procedure-specific: for colectomy, oesophagectomy, lung resection, pancreatectomy and prostatectomy, very high-volume hospitals had both lower PSI event rates and lower failure-to-rescue rates. For gastrectomy, very high-volume hospitals did not have lower PSI event rates but they did have lower failure-to-rescue rates; for hysterectomy, very high-volume hospitals had higher PSI event rates, but had lower failure-to-rescue rates; for cystectomy, very high volume-hospitals had lower PSI event rates and a trend towards lower failure-to-rescue rates.

Table 4.

Impact of hospital volume effect on patient safety indicator event occurrence and on failure to rescue (death after patient safety indicator event) from individual multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for hospital clustering by generalised estimating equation in patients undergoing major cancer surgery, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1999–2009

| Patient safety indicator occurrence* |

Failure to rescue* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Overall | ||||

| 1st volume quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd volume quartile | 0.945 (0.922 to 0.969) | <0.001 | 0.920 (0.861 to 0.982) | 0.013 |

| 3rd volume quartile | 0.883 (0.860 to 0.907) | <0.001 | 0.842 (0.784 to 0.904) | <0.001 |

| 4th volume quartile | 0.761 (0.739 to 0.783) | <0.001 | 0.716 (0.661 to 0.775) | <0.001 |

| Colectomy | ||||

| 1st volume quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd volume quartile | 1.007 (0.969 to 1.046) | 0.728 | 1.029 (0.936 to 1.132) | 0.553 |

| 3rd volume quartile | 0.940 (0.902 to 0.980) | 0.003 | 0.978 (0.883 to 1.083) | 0.670 |

| 4th volume quartile | 0.842 (0.805 to 0.881) | <0.001 | 0.831 (0.742 to 0.931) | 0.001 |

| Cystectomy | ||||

| 1st volume quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd volume quartile | 0.816 (0.728 to 0.914) | <0.001 | 0.872 (0.642 to 1.185) | 0.382 |

| 3rd volume quartile | 0.760 (0.672 to 0.860) | <0.001 | 0.691 (0.487 to 0.981) | 0.039 |

| 4th volume quartile | 0.585 (0.509 to 0.671) | <0.001 | 0.706 (0.471 to 1.058) | 0.092 |

| Oesophagectomy | ||||

| 1st volume quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd volume quartile | 0.802 (0.653 to 0.986) | 0.037 | 0.633 (0.432 to 0.928) | 0.019 |

| 3rd volume quartile | 0.687 (0.546 to 0.863) | 0.001 | 0.488 (0.309 to 0.770) | 0.002 |

| 4th volume quartile | 0.479 (0.378 to 0.609) | <0.001 | 0.459 (0.280 to 0.753) | 0.002 |

| Gastrectomy | ||||

| 1st volume quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd volume quartile | 1.043 (0.935 to 1.163) | 0.455 | 1.028 (0.820 to 1.289) | 0.812 |

| 3rd volume quartile | 0.973 (0.866 to 1.093) | 0.642 | 0.847 (0.660 to 1.088) | 0.193 |

| 4th volume quartile | 0.905 (0.795 to 1.030) | 0.129 | 0.709 (0.532 to 0.945) | 0.019 |

| Hysterectomy | ||||

| 1st volume quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd volume quartile | 1.044 (0.930 to 1.172) | 0.468 | 0.955 (0.895 to 1.020 | 0.168 |

| 3rd volume quartile | 1.264 (1.118 to 1.428) | <0.001 | 0.874 (0.815 to 0.938) | <0.001 |

| 4th volume quartile | 1.231 (1.083 to 1.399) | 0.001 | 0.758 (0.701 to 0.820) | <0.001 |

| Lung | ||||

| 1st volume quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd volume quartile | 0.954 (0.911 to 1.000) | 0.048 | 0.820 (0.720 to 0.934) | 0.003 |

| 3rd volume quartile | 0.910 (0.866 to 0.956) | <0.001 | 0.755 (0.657 to 0.867) | <0.001 |

| 4th volume quartile | 0.792 (0.750 to 0.836) | <0.001 | 0.643 (0.548 to 0.753) | <0.001 |

| Pancreatectomy | ||||

| 1st volume quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd volume quartile | 0.767 (0.676 to 0.870) | <0.001 | 0.598 (0.460 to 0.775) | <0.001 |

| 3rd volume quartile | 0.539 (0.468 to 0.621) | <0.001 | 0.405 (0.291 to 0.564) | <0.001 |

| 4th volume quartile | 0.416 (0.357 to 0.485) | <0.001 | 0.362 (0.250 to 0.525) | <0.001 |

| Prostatectomy | ||||

| 1st volume quartile | 1.0 (ref.) | – | 1.0 (ref.) | – |

| 2nd volume quartile | 0.772 (0.713 to 0.837) | <0.001 | 1.293 (0.696 to 2.403) | 0.415 |

| 3rd volume quartile | 0.736 (0.673 to 0.805) | <0.001 | 1.335 (0.687 to 2.591) | 0.394 |

| 4th volume quartile | 0.541 (0.488 to 0.600) | <0.001 | 0.293 (0.085 to 1.006) | 0.051 |

*Multivariable models were generated for the overall model and for each procedure individually. Only the OR and 95% CI for hospital volume are displayed in the table. Other covariates in each model included: age, gender, race, comorbidities, median household income by ZIP code, hospital location, teaching status, region, year of admission and procedure type (for overall model only).

Discussion

Recently, it has been estimated that the annual cost of medical errors is over 17 billion dollars19 and there have been a slew of newer initiatives over the last decade to incentivise better quality care. In 2008, Medicare announced that it would restrain the ability of hospitals to get reimbursed for ‘reasonably preventable events’: avoidable medical errors ranging from pressure ulcers, falls and transfusion of incompatible blood to anaesthetic complications, deep vein thrombosis and foreign bodies left in the body of patients during surgery. These and other initiatives are designed to place the burden of responsibility for such hospital-acquired adverse events squarely on hospitals and physicians.20 While these initiatives have been met with stiff objection from hospital administrations, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) has been consistent in its position that accountability for such events should rest with hospitals and not with the taxpayer.20 The Affordable Care Act of 2010 has added newer dimensions to these quality-improvement initiatives, with reimbursement likely to be dependent on both adherence to standards of care and the perceptions of patients with regard to hospital performance as measured by surveys.21

A rational approach to improving accountability for substandard care should begin with identifying the true burden of hospital-acquired adverse events. This would be particularly useful in identifying specific adverse events that warrant special attention by payers like CMS and in preferential allocation of resources by hospitals due to the growing temporal burden of such events.

In the current study, we report contemporary trends in the frequency of hospital-acquired adverse events after major surgical oncology care in the USA. Our study has a number of novel findings. First, we report a gradual increase in the national frequency of hospital-acquired adverse events after major cancer surgery over the last decade. This is important as it represents a decline, albeit small and gradual, in the quality of surgical oncology care at the national level, as measured by the primary prevention of PSI events. The increase may be attributed to changes in case-mix, including an ageing population. Conversely, the emergence of multiresistant bacteria may contribute to the recorded trends.22 23 Second, a simultaneous decrease in failure-to-rescue rates was observed, which may indicate that while primary prevention of hospital-acquired adverse events has deteriorated, the early recognition and timely management of these complications may have improved in the last decade. These findings may explain the significant annual reduction in mortality for patients undergoing major cancer surgery. Nonetheless, alternate explanations include refinements in coding practices, which may have led to better recognition and recording of non-lethal adverse events, thereby resulting in an apparent decrease in mortality rates. Third, significant heterogeneity in the temporal dynamics of specific hospital-acquired adverse events was noted. While marked and worrisome increases were recorded in the frequency of postoperative sepsis, pressure ulcers and respiratory failure, advances were made in the prevention of anaesthetic complications, transfusion-related complications and hip fractures. Thus, we identify numerous setting-level and process-level measures where resources need to be refocused for further improvement in the quality of surgical oncology care.

We also examined the volume-complication-mortality dynamic in patients undergoing major cancer surgery, as it applies to potentially preventable hospital-acquired adverse events (PSI). There is a well-established body of evidence describing the volume-mortality relationship in patients undergoing major cancer procedures and other surgeries. Dudley et al24 examined patients undergoing 1 of 11 diverse procedures (ranging from coronary angioplasty to oesophageal cancer surgery) in California and concluded that 602 deaths could have been prevented annually by transferring patients from low-volume to high-volume hospitals. Birkmeyer et al25 reported that Medicare patients treated at very high-volume hospitals experienced up to a 12% difference in absolute mortality for certain procedures relative to patients treated at very low-volume hospitals. However, the underlying mechanisms explaining the volume-mortality relationship have not been elucidated clearly. Silber et al26 first introduced the concept of ‘failure-to-rescue’ in a seminal report that evaluated patients undergoing cholecystectomy or transurethral prostatectomy. They concluded that overall mortality was related to both hospital-level and patient-level factors, while adverse events were related to patient-level factors at admission (severity of illness). However, failure-to-rescue was preferentially associated with hospital-level factors, and thus the underlying dynamics for failure-to-rescue were different than that for overall mortality and adverse events. The current hypothesis8 regarding the volume-complication-mortality relationship is that lower volume hospitals experience higher mortality rates not because of higher complication rates, but due to lower failure-to-rescue rates. Ghaferi et al10 demonstrated that high-volume and low-volume hospitals enrolled in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program had similar complication rates but different failure-to-rescue rates for multiple procedures. In a subsequent analysis9 of patients undergoing gastrectomy, pancreatectomy or oesophagectomy, similar results were demonstrated. However, in the current study, very high-volume hospitals (4th quartile vs 1st quartile) had both lower PSI event rates and lower failure-to-rescue rates. Importantly, the volume-complication-mortality relationship, as it applies to PSI events, appears to be procedure-specific and heterogeneous, with the current hypothesis not accounting for multiple individual major cancer surgeries, namely colectomy, oesophagectomy, lung resection, pancreatectomy and prostatectomy. This is an important point: CMS currently focuses its quality-improvement initiatives on complication rates, and explicit demonstration that lower failure-to-rescue rates and not higher complication rates underlying the substandard care at low-volume hospitals may require a reconsideration of these initiatives. Our findings indicate that the prevailing hypothesis may need to be re-evaluated, at least for patients undergoing major cancer surgery. In fact, for patients undergoing hysterectomy, this relationship is reversed, with patients at very high-volume hospitals experiencing higher PSI event rates and lower failure-to-rescue rates. The underlying reason for this finding is not clear. Previous studies27 have questioned the impact of hospital volume on hysterectomy outcomes and reported that surgeon volume trumps hospital volume as the predominant factor underlying the volume–outcomes relationship for hysterectomy. While the inclusion of surgeon volume may alter these findings, the higher rates of adverse events in patients undergoing hysterectomy at very high-volume hospitals may need to be re-examined in future reports.

Our study is not without limitations. The drawbacks of using administrative data are well known,28 including limitations regarding risk-adjustment and miscoding. While PSIs have been shown to perform well as screening tools from an epidemiological perspective (overidentification and few false-negatives), problems related to high false-positive rates exist, with most validation studies reporting positive predictive values of between 43% and >90%.29 30 While it is clear that these drawbacks limit the use of PSIs to make reimbursement decisions or to compare hospitals, it is unclear how it affects the implications of our study, where it was used as a screening tool to identify adverse events.29 30 Second, morbidity and mortality events in NIS are characterised based on the index admission, and subsequent readmissions, while relevant, are not recorded. This may have resulted in under-recognition of the true burden of adverse events, mortality and charges after the initial cancer surgery. Third, while the heterogeneity identified in the volume–complication–mortality relationship is a key finding in the present report, our study design does not allow for the identification of the underlying mechanisms explaining these results. It is also important to emphasise that, in contrast to the previously cited studies where the overall complication rates were examined, we evaluated potentially preventable hospital-acquired events only. Previous investigators have shown that this restricted definition has limitations since not all deaths are accounted for in a given population sample31; alternatively, these drawbacks may not apply to studies focusing on patient safety using PSI as a quality-of-care measure. Hence, while it may not be illogical to expect lower volume hospitals to provide substandard care secondary to both higher rates of preventable adverse events and higher failure-to-rescue rates, it is certainly possible that a majority of hospital-acquired complications are an inevitable result of procedure complexity and patient comorbidities (and not just a failure of setting-level prevention measures). Consequently, while more rigorous patient care pathways might explain the lower incidence of preventable adverse events and subsequent mortality in higher volume hospitals, for the majority of (non-preventable) adverse events, the incidence rates would be the same regardless of hospital volume with lower failure-to-rescue rates preferentially explaining the low mortality rates of higher volume hospitals. Further investigation of these findings is required to test these possibilities and to fully understand the underlying dynamics of the volume–mortality relationship.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, there has been a substantial increase in the national frequency of potentially avoidable hospital-acquired adverse events after major cancer surgery, with a detrimental effect on numerous outcome-level measures. However, there was a concomitant reduction in failure-to-rescue rates and, consequently, overall mortality rates. Policy changes and resource reallocation to improve the increasing burden of specific adverse events, such as postoperative sepsis, pressure ulcer and respiratory failure, are required.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

| Patient safety indicator | ICD-9-CM |

|---|---|

| Anaesthetic complications | E8763, E9381, E9382, E9383, E9384, E9385, E9386, E9387, E9389, 9681, 9682, 9683, 9684, 9687, E8551 |

| Pressure ulcers | 7072x, 7070, 70700, 70701, 70702, 70703, 70704, 70705, 70706, 70707,70709 |

| Foreign body | 9984, 9987, E871x |

| Iatrogenic pneumothorax | 5121 |

| Central venous catheter-related blood stream infection | 99662, 9993, 99931, 99932 |

| Postoperative hip fracture | 820xx |

| Postoperative haemorrhage or haematoma | 9981x, 388x, 3941, 3998, 4995, 5793, 6094, 1809, 540, 5412, 6094, 5919, 610, 6998, 7014,7109,7591, 7592, 8604 |

| Postoperative physiological and metabolic derangement (secondary diabetes or acute kidney failure) | 249x, 2501x, 2502x, 2503x, 584x, 586, 9975 |

| Postoperative physiological and metabolic derangement (dialysis) | 3995, 5498 |

| Postoperative respiratory failure | 5185X, 51881, 51884, 9672, 9670, 9671, 9604 |

| Postoperative deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus | 4511x, 4512, 45181, 4519, 4534x, 4538, 4539, 4151x |

| Postoperative sepsis | 038x, 038xx, 9980x, 9959x |

| Postoperative wound dehiscence | 5461 |

| Accidental puncture or laceration | E870x, 9982 |

| Transfusion reaction | 9996x, 9997x, E8760 |

Footnotes

Contributors: SS, FR and Q-DT conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. SS and FR contributed equally. SS, VQT and FR performed the data analyses. VQT produced the tables and graphs. JDS and MS provided input into the data analysis. MS was responsible for the acquisition of the data and M-KG, H-JT, PR, SPK, JCH, PIK, JN, MS and MM contributed to the interpretation of the results. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by SS and FR and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: An institutional review board waiver was obtained in accordance with institutional policy when dealing with population-based de-identified data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Iezzoni LI, Foley SM, Heeren T, et al. A method for screening the quality of hospital care using administrative data: preliminary validation results. Qual Rev Bull 1992;18:361–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/modules/psi_resources.aspx (accessed 9 Sep 2012)

- 3.Zhan C, Miller MR. Excess length of stay, charges, and mortality attributable to medical injuries during hospitalization. JAMA 2003;290:1868–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downey JR, Hernandez-Boussard T, Banka G, et al. Is patient safety improving? National trends in patient safety indicators: 1998–2007. Health Serv Res 2012;47(1 Pt 2):414–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:10–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross JS, Bradley EH, Busch SH. Use of health care services by lower-income and higher-income uninsured adults. JAMA 2006;295:2027–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu JH, Zingmond DS, McGory ML, et al. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume hospitals for complex surgery. JAMA 2006;296:1973–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghaferi AA, Dimick JB. Variation in mortality after high-risk cancer surgery: failure to rescue. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2012;21:389–95, vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital volume and failure to rescue with high-risk surgery. Med Care 2011;49:1076–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1368–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp (accessed 9 Sep 2012)

- 12.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis 1987;40:373–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deyo R, Cherkin D, Ciol M. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Census Bureau. 2000. [cited 2010]. http://www.census.gov.

- 15.Trinh QD, Sun M, Sammon J, et al. Disparities in access to care at high-volume institutions for uro-oncologic procedures. Cancer 2012;118:4421–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Modules/PSI_TechSpec.aspx (accessed 9 Sep 2012)

- 17.Anderson WF, Camargo MC, Fraumeni JF, Jr, et al. Age-specific trends in incidence of noncardia gastric cancer in US adults. JAMA 2010;303:1723–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panageas KS, Schrag D, Riedel E, et al. The effect of clustering of outcomes on the association of procedure volume and surgical outcomes. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:658–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Den Bos J, Rustagi K, Gray T, et al. The $17.1 billion problem: the annual cost of measurable medical errors. Health Aff (Project Hope) 2011;30:596–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milstein A. Ending extra payment for ‘never events’—stronger incentives for patients’ safety. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2388–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. http://patients.about.com/od/AffordableCareAct/a/Affordable-Care-Act-And-Patient-Satisfaction-In-Hospitals.htm (accessed 9 Sep 2012)

- 22.Wellington EM, Boxall AB, Cross P, et al. The role of the natural environment in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:155–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaye KS, Schmader KE, Sawyer R. Surgical site infection in the elderly population. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:1835–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudley RA, Johansen KL, Brand R, et al. Selective referral to high-volume hospitals: estimating potentially avoidable deaths. JAMA 2000;283:1159–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1128–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, et al. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery. A study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Med Care 1992;30:615–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright JD, Lewin SN, Deutsch I, et al. Effect of surgical volume on morbidity and mortality of abdominal hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:1051–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarrazin MS, Rosenthal GE. Finding pure and simple truths with administrative data. JAMA 2012;307:1433–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson KE, Recktenwald A, Reichley RM, et al. Clinical validation of the AHRQ postoperative venous thromboembolism patient safety indicator. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2009; 35:370–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaafarani HM, Borzecki AM, Itani KM, et al. Validity of selected patient safety indicators: opportunities and concerns. J Am Coll Surg 2011;212:924–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silber JH, Romano PS, Rosen AK, et al. Failure-to-rescue: comparing definitions to measure quality of care. Med Care 2007;45:918–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.