Abstract

Objective

To quantify and draw inferences on the clinical effectiveness of platelet-rich therapy in the management of patients with a typical osteoporotic fracture of the hip.

Design

Single centre, parallel group, participant-blinded, randomised controlled trial.

Setting

UK Major Trauma Centre.

Participants

200 of 315 eligible patients aged 65 years and over with any type of intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur. Patients were excluded if their fracture precluded internal fixation.

Interventions

Participants underwent internal fixation of the fracture with cannulated screws and were randomly allocated to receive an injection of platelet-rich plasma into the fracture site or not.

Main outcome measures

Failure of fixation within 12 months, defined as any revision surgery.

Results

Primary outcome data were available for 82 of 101 and 78 of 99 participants allocated to test and control groups, respectively; the remainder died prior to final follow-up. There was an absolute risk reduction of 5.6% (95% CI −10.6% to 21.8%) favouring treatment with platelet-rich therapy (χ2 test, p=0.569). An adjusted effect estimate from a logistic regression model was similar (OR=0.71, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.40, z test; p=0.325). There were no significant differences in any of the secondary outcome measures excepting length of stay favouring treatment with platelet-rich therapy (median difference 8 days, Mann-Whitney U test; p=0.03). The number and distribution of adverse events were similar. Estimated cumulative incidence functions for the competing events of death and revision demonstrated no evidence of a significant treatment effect (HR 0.895, 95% CI 0.533 to 1.504; p=0.680 in favour of platelet-rich therapy).

Conclusions

No evidence of a difference in the risk of revision surgery within 1 year in participants treated with platelet-rich therapy compared with those not treated. However, we cannot definitively exclude a clinically meaningful difference.

Trial registration

Current Controlled Trials, ISRCTN49197425, http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN49197425

Keywords: Rheumatology

Article summary.

Article focus

To explore the difference in the risk of fixation failure at 1 year after index fracture between patients treated with platelet-rich therapy and those not as an adjunct to internal fixation of an intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur.

Key messages

No evidence of a difference in the risk of revision surgery within 1 year in participants treated with platelet-rich therapy compared with those not treated.

A clinically meaningful difference cannot be definitively excluded.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Pragmatic trial.

Includes participants with chronic cognitive impairment.

Introduction

Platelet-rich therapies are autologous blood products with a greater concentration of platelets than physiological whole blood.1 These preparations have been used since the early 1990s to promote bone and soft tissue healing.1 Promising preliminary studies have led to the use of platelet-rich therapy in sports medicine, rheumatology and orthopaedic surgery with the aim of promoting and enhancing soft tissue and bone healing.2

Platelet-rich therapies can be produced at the bedside by either centrifugation or filtering of autologous whole blood mixed with an anticoagulant. Both these processes produce a plasma fraction that has a supraphysiological concentration of platelets. Platelets have long been identified as the main regulators of the inflammatory phase of tissue repair.3 This same mechanism may also influence the proliferation and differentiation phases of healing tissues.3 Hence, platelet-rich therapy has been used in an attempt to optimise healing by delivering supraphysiological levels of platelet-derived growth factors to the site of injury.4

At present, good-quality evidence to support the use of platelet-rich therapy in the clinical setting remains sparse. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has advised that its use should be restricted to research settings.5 One exciting area of research is the use of platelet-rich therapy to enhance healing in osteoporotic fractures.6

Intracapsular fractures of the proximal femur are a good example. Failure of internal fixation for these hip fractures is common, with up to 35% of displaced fractures requiring revision surgery.7–9 Therefore, any adjunct that can accelerate fracture healing and reduce the rate of failure of fixation has the potential to change patient care.

We conducted a randomised controlled trial to quantify and draw inferences on the clinical effectiveness of platelet-rich therapy in the management of patients with a typical osteoporotic fracture of the hip. Specifically, we sought to explore the difference in the risk of fixation failure at 1 year after index fracture between patients treated with platelet-rich therapy and those not as an adjunct to internal fixation of an intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur.

Methods

This study was a single centre, parallel group, participant-blinded, randomised standard-of-care controlled trial with a 1:1 allocation to main treatment groups. Full details of the protocol have been published elsewhere.10 The trial was given ethical approval on 6 July 2009 by the Coventry Research Ethics Committee (09/H1210/22).

Participants

All patients aged 65 years and above with an intracapsular hip fracture were eligible, including those with cognitive impairment. Patients were excluded if they were managed non-operatively, presented late following their injury, had serious injuries to either lower limb that interfered with rehabilitation of the hip fracture, or had extant local disease precluding fixation, for example, local tumour deposit and symptomatic ipsilateral hip osteoarthrosis.

Recruitment and allocation of participants

Participants were recruited between September 2009 and April 2011 from the acute trauma admissions to University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire National Health Service (NHS) Trust, Coventry, UK. This is a major trauma centre that serves a population of two million people. Approximately 650 patients per year with a fracture of the proximal femur are treated in the centre.11 Participants with capacity gave written consent; for those who lacked capacity, written consent was given by a consultee in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

Participants were randomly allocated to one of two groups: standard-of-care fixation or standard-of-care fixation and platelet-rich therapy injection. Treatment allocation was determined using a computer generated, randomised number sequence administrated by an independent clinical trials unit via a secure online programme. The randomisation code was stratified by displacement of the fracture12 and split into unequal block sizes. Stratification ensured that those fractures which were minimally displaced that are associated with a very substantially improved outcome, were distributed evenly between the groups. The code was only broken at the end of the trial once the trial statistician had locked and analysed the dataset.

Allocation to the treatment group took place intraoperatively, only after the operating surgeon confirmed a successful reduction of the fracture. Those patients in whom a reduction could not be achieved underwent hip arthroplasty, which reflects standard clinical practice.

Interventions

All participants underwent closed reduction of their fracture, where the leg was manipulated until the bones were ‘reduced’ back into their normal anatomical position. The lower limb was supported on a fracture table. Internal fixation of the fracture was achieved through a standard lateral approach with perioperative antibiotic cover in accordance with hospital protocol. Postoperative care was the same for both groups of patients with early active mobilisation and immediate full weight bearing with a standardised physiotherapy rehabilitation regime. All participants received routine prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis.

Standard-of-care fixation was with two or three parallel cannulated screws. The number and exact configuration was left to the discretion of the operating surgeon to ensure that the results could be easily generalised. For those participants allocated to platelet-rich therapy, each screw was advanced up to but not beyond the fracture such that no compression was achieved before the platelet-rich plasma was injected. The guidewire of one screw was then removed and 3 mL of platelet-rich plasma, harvested in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations (GenesisCS Component Concentrating System, EmCyte Corporation, Fort Myers, Florida, USA), was injected without an activator through the cannulated screw directly into the fracture site under image intensifier guidance. This preparation is a Mishra et al's13 type 1A platelet-rich plasma, whose details of bioactivity are available elsewhere.14 15 The guidewire was immediately replaced and the screws advanced across the fracture site. No attempt was made to blind the operating surgeon.

Outcome measurements

Primary

The proportion of participants undergoing reoperation for failure of fixation within 1 year of sustaining the fracture.

Secondary

Radiographic non-union at 1 year. Non-union was defined as “failure of the fracture to show signs of bony union on the anteroposterior or lateral radiograph 1 year after surgery.”8

Radiographic evidence of avascular necrosis at 1 year.

The EuroQoL 5 Dimensions Index (EQ-5D), York A1 value set16 at 6, 12 and 52 weeks.

Length of index hospital stay.

Mortality.

Adverse events.

Sample size

Very few data were available to estimate the possible size of a treatment effect of platelet-rich therapy.17 18 The minimum clinically important treatment effect of platelet-rich therapy was agreed in discussion with several expert orthopaedic trauma surgeons. Although the figures varied by surgeon, all agreed that an absolute risk reduction (ARR) of between 15% and 25% in fixation failure would be clinically important. The overall rate of fixation failure of all intracapsular fractures of the femur is reported to be between 25% and 35%.7–9 Sample sizes were determined using the PS power and sample size software.19 Selecting a power of 90%, and the most plausible estimate of fixation failure rate (30%) and an intermediate value for the minimum clinically important ARR of 20% gives a treatment group size of 82. Adding 20% on to the total trial sample size estimate to account for expected patient mortality gives a recruitment target of 200 participants that should provide a good margin for unanticipated recruitment problems and loss to follow-up.

Statistical methods

The primary outcome measure, the proportion of patients requiring reoperation for failure of fixation (revision) within 1 year of sustaining the fracture, was compared between treatment groups (fixation and fixation plus platelet-rich therapy) using a χ2 test, where data from participants were analysed by treatment allocation. Treatments were considered to differ significantly if p values were less than 0.05. The primary analysis was an available case analysis where deaths without revision were excluded from the analysis. If mortality differed between the treatment groups, this had the potential to bias the effect estimate, so additional post hoc analyses were undertaken with deaths imputed as both revisions and non-revisions to assess the sensitivity of the primary analysis to the decisions regarding handling of the missing data.

Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the significance of observed differences for the secondary proportional outcome measures. For continuous outcomes, which were approximately normally distributed, mean differences (MDs) were tested using a two-tailed t test; for non-parametric data (length of stay), differences were tested with the Mann-Whitney U test. A planned subsidiary analysis used a multiple linear regression model to investigate the relationship between each participant's EQ-5D score at 1 year postoperatively and the treatment group, after appropriate adjustment for age, sex and fracture displacement for each participant. The incidences of adverse events were reported for each treatment group stratified by the type of event. Planned subgroup analyses were undertaken only for prespecified subgroups. Explanatory variables of sex, fracture displacement, dementia and age were entered into a logistic regression model with associated interaction terms with the treatment arm for each.

In addition to the primary analysis comparing risks of revision between groups, the Data Monitoring Committee recommended that a post hoc time-to-event analysis was also undertaken to assess temporal differences in revision post operation. In this setting, where failure of the fixation was the event of interest, death was regarded as a competing risk. In the presence of competing risks, the standard cause-specific Cox proportional hazards model is not appropriate as it treats the competing risk (death) as a censored observation. Therefore, the approach adopted here was the proportional hazards model proposed by Fine and Gray,20 based on direct regression modelling of covariates on the cumulative incidence function (CIF). CIF, the proportion of trial participants at time t who had event j (death or revision), was used to compare treatments, and the R software21 package cmprsk22 was used to implement the Fine-Gray model using a stepwise fitting algorithm.

Results

Participants

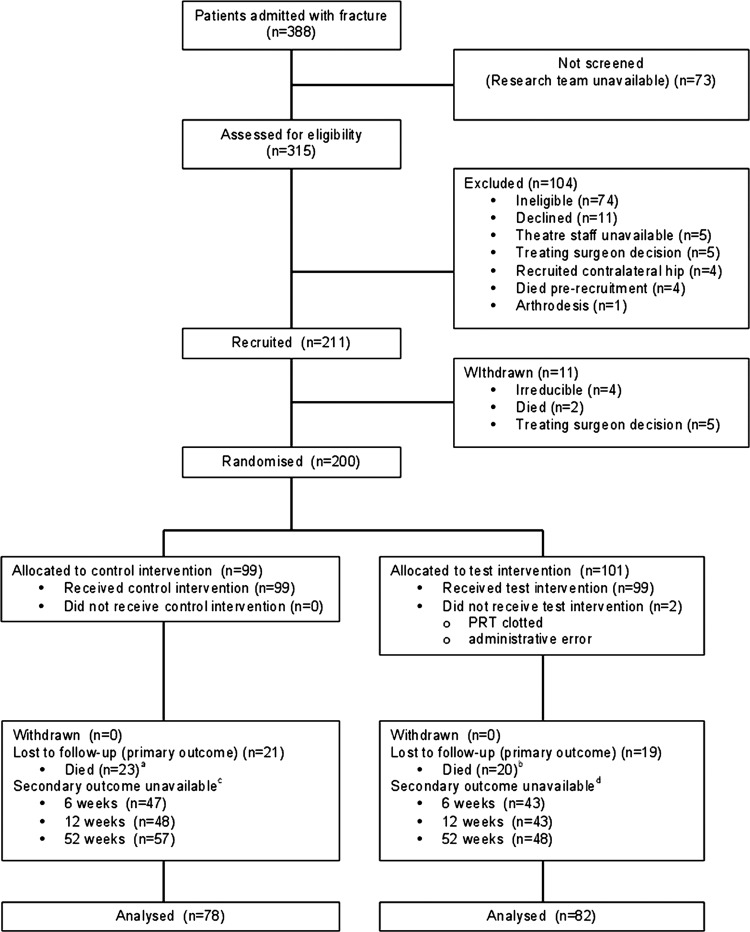

A summary of the flow of participants through the study is at figure 1. Of the 388 patients admitted with an intracapsular hip fracture during the recruitment period, 52% underwent trial treatments, which represented 83% of all eligible patients assessed. This was largely due to recruitment only taking place during the working week.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). Notes: (a) Two participants underwent revision prior to death, (b) 1 participant underwent revision prior to death, (c) 31 participants unavailable at baseline and (d) 35 participants unavailable at baseline.

Two hundred and eleven participants were enrolled into the study, of whom 200 were randomly allocated to treatments. Ninety-nine participants were allocated to the control group, of whom 76 completed the trial protocol; 101 were allocated to the test group, of whom 81 completed the protocol. In the latter group, there were three protocol violations leading to three crossovers. Of the 43 participants who died, 3 underwent revision surgery prior to death, so in total 160 participants were available for the primary analysis. The numbers of participants unavailable at each of the four time points for the EQ-5D score are reported in the trial flow diagram (figure 1). Similar proportions of other secondary outcomes were unavailable at different follow-up time points due to death, coexisting chronic confusional states at the time of recruitment, new onset comorbidities and participant withdrawals.

The baseline characteristics of the trial participants are described in table 1. There were no apparently substantial between-group differences for any of the recorded baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for each group

| Characteristics | Group |

|

|---|---|---|

| Control (n=99) | Test (n=101) | |

| Age (years) | 83 (7.8) | 83 (8.2) |

| Female (%) | 73 | 69 |

| Minimally displaced fractures (%) | 22 | 21 |

| Demented (AMT <8) | 31 | 34 |

| Premorbid EQ-5D | 0.63 (0.34) | 0.69 (0.30) |

| Previously diagnosed CRF (%) | 4.0 | 4.9 |

| Previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus (%) | 6.1 | 16 |

| Previously diagnosed osteoporosis (%) | 18 | 18 |

| Currently prescribed antiplatelet drug (%) | 32 | 27 |

| Previously or currently prescribed systemic steroid (%) | 6.1 | 6.9 |

| Currently prescribed NSAID (%) | 4.0 | 3.9 |

| Currently smoking (%) | 8.1 | 7.9 |

| Time to theatre (hours) | 34 (33) | 30 (26) |

Summary statistics: mean (SD).

AMT, abbreviated mental test score; CRF, chronic renal failure; EQ-5D, EuroQoL 5 Dimensions Index; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Treatments

Both the test and control treatments were successfully delivered as described previously, under the supervision of 18 consultant trauma surgeons and performed by a total of 21 specialist trainees.

Outcomes and estimation

Table 2 shows the counts and estimated risks of revision surgery by treatment group. There was an ARR of 5.6% (95% CI −10.6% to 21.8%) in favour of platelet-rich therapy (χ2 test, p=0.569).

Table 2.

Revision at 12 months post index operation

| Group | Unrevised | Revised | Total | Risk (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 47 | 31 | 78 | 39.74 |

| Test | 54 | 28 | 82 | 34.15 |

| Total | 101 | 59 | 160 | 36.88 |

Deaths were also approximately balanced between treatment groups (control n=23 and test n=20). Imputing all the deaths as ‘revisions’ increased the overall estimates of revision risks, but due to the balance across groups, it had little impact on effect estimates (control risk 52.5%; ARR in favour of platelet-rich therapy 6%, 95% CI −8.8% to 20.8%; χ2 test p=0.480). Similarly, an equivalent analysis recoding deaths as ‘non-revisions’ did not modify the conclusions of the primary analysis (control risk 31.3%; ARR in favour of platelet-rich therapy 3.6%, 95% CI −10.0% to 17.2%, χ2 test; p=0.688).

Logistic regression analysis, with a binary response variable (1=revised and 0=unrevised), was used to assess the effect of treatment group allocation on revision after adjustment for sex, fracture displacement, dementia and age. This model gave an adjusted estimated OR of 0.71 (95% CI 0.36 to 1.40), which was marginally smaller than the unadjusted OR of 0.79 from table 2, and provided no evidence for a significant treatment effect (z test from logistic regression, p=0.325). In addition to the planned variables used for the adjusted analysis, other baseline variables (eg, diabetes) were also entered into the regression model, but proved not to be significant. Interaction terms were added to the model to test for prespecified subgroup effects; that is, additional terms were included in the model that tested to see if the treatment effect was changed (moderated) by fracture displacement, dementia or age group. Appropriate interaction terms were added individually to the base model to give three separate analyses; none of the interaction terms significantly improved the model fit, providing no evidence for substantial subgroup effects.

There was no significant difference in the unadjusted mean EQ-5D score at 1 year between the control and treatment groups (mean control group EQ-5D=0.588, MD=0.018 in favour of the control group, t test; p=0.799). After adjusting for age, sex and fracture displacement, this was maintained. A summary of the other secondary outcomes is presented in table 3. There was no significant difference between treatment groups in any of the measures excepting length of stay. The number and distribution of complications were similar in both treatment groups (table 4).

Table 3.

Between-group differences in secondary outcome measures

| Outcome | Treatment group |

Test | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=78) | Test (n=82) | |||

| Radiographic non-union at 1 year (%) | 1 | 2 | Fisher's exact | 1.00 |

| Radiographic avascular necrosis at 1 year (%) | 1 | 2 | Fisher's exact | 1.00 |

| Length of index hospital stay (days) | 23 (10–41) | 15 (7–27) | Mann-Whitney | 0.03 |

| Mortality (%) | 23 | 20 | Fisher's exact | 0.61 |

Proportions are expressed as percentages; summary statistics as median and IQR.

Table 4.

Between-group differences in complications

| Complication | Absolute number of events |

|

|---|---|---|

| Control group (n=99) | Test group (n=101) | |

| Wound infection | 3 | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolus | 2 | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 12 | 9 |

| Urinary tract infection | 6 | 5 |

| Blood transfusion | 2 | 0 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 | 0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 | 0 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2 | 2 |

| Death | 23 | 20 |

Events are not mutually exclusive.

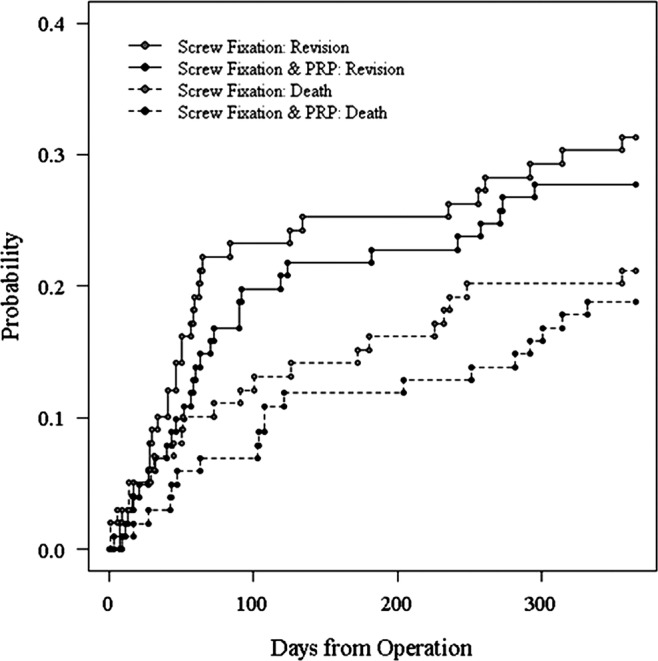

Estimated CIF curves, the probability that the event of interest occurs before a given time, are shown for death and revision as competing events for each treatment group in figure 2. Estimates of HR for the competing risks regression model are reported in table 5. The estimates indicated an increased risk of revision surgery for participants with a pre-existing diagnosis of osteoporosis and a significantly lower risk for participants with minimally displaced fractures or dementia. There was no evidence for a significant treatment effect (HR 0.895, 95% CI 0.533 to 1.504; p=0.680 in favour of platelet-rich therapy). An analogous time-to-event analysis using the more conventional Cox proportional hazards model gave very similar results (HR 0.819, 95% CI 0.489 to 1.372; p=0.449 in favour of platelet-rich therapy).

Figure 2.

Estimated cumulative incidence function curves death and revision as competing events for each treatment group.

Table 5.

Estimates of HRs for competing risks model

| Covariate | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Displacement | |||

| Minimally displaced | 0.303 | 0.126 to 0.730 | 0.008 |

| Displaced | 1 | – | – |

| Steroids | |||

| Yes | 0.165 | 0.022 to 1.217 | 0.077 |

| No | 1 | – | – |

| Previously diagnosed osteoporosis | |||

| Yes | 2.207 | 1.153 to 4.223 | 0.017 |

| No | 1 | – | – |

| Demented | |||

| Yes | 0.496 | 0.263 to 0.937 | 0.031 |

| No | 1 | – | – |

| Treatment | |||

| Test | 0.895 | 0.533 to 1.504 | 0.680 |

| Control | 1 | – | – |

Discussion

Principal findings

This trial has found no evidence of a difference in the risk of revision surgery between participants receiving platelet-rich therapy and those not as an adjunct to internal fixation of an intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur. However, we have been unable to definitively exclude a clinically important difference. A sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of decisions regarding the handling of the missing data and the competing risks of death and revision surgery found similar estimates of the effect size.

The majority of secondary outcomes, including radiographic, mortality and patient-reported health-related quality-of-life measures, demonstrated effects that were concordant with the primary outcome. The length of inpatient stay was significantly shorter in the group treated with platelet-rich therapy. We are unable to provide a biologically plausible explanation for this difference. There was no evidence of any subgroup interaction effects.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This was a pragmatic trial. Although it was only conducted at a single centre, a large number of surgeons were involved in the administration of both the interventions. The consequent variety in reduction and fixation strategies probably reflects wider surgical practice in a well-recognised cohort of patients. The corollary of this, that the case number for any one surgeon was comparatively low, might have reduced the assay sensitivity of the trial. However, each surgeon was either trained to perform the intervention or supervised suitably. Additionally, since each individual surgeon performed only a small number of interventions, the impact of the ‘surgeon effect’, related to both experience and technical expertise, was likely to have been small.

The hypothesis of the trial concerned the incidence of fixation failure. Since it is difficult to define a surrogate outcome of revision, surgery was chosen. It is possible that other considerations, such as patient comorbidity, may have influenced any decision to undertake revision surgery. However, it is unlikely that such considerations differed between the treatment groups.

Only 80% of the available population was screened for eligibility since the trial staff was often not available outside the working week. This might have produced a sampling bias. However, a review of the admission and screening data revealed no substantial differences in the crucial confounders of age, sex, fracture displacement and chronic cognitive impairment between the unscreened and recruited samples.

Some participants were being treated with antiplatelet drugs at the time of recruitment into the trial. These participants were not excluded since the trial was pragmatic and there is no evidence that the mechanism of release of the platelet-derived growth factors during platelet-rich therapy administration are dependent on the pathways inhibited by aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs.

Comparison with other studies

Few data exist from other similar studies with which to compare these findings.17 Indeed, to our knowledge, this is the first trial of this size to be conducted exploring platelet-rich therapy in bone healing.2

Our modelling demonstrated that fracture displacement and a pre-existing diagnosis of osteoporosis were significant predictors of revision risk. This is consistent with clinical experience and previous authors’ findings.8 The cohort study reported by Parker et al8 recruited more participants than this trial and identified risk factors with smaller effect sizes. Interestingly, our model found that dementia was a protective factor. It is difficult to develop a biologically plausible explanation for this observation. It may rather reflect the reluctance to embark upon major revision arthroplasty surgery in this group of particularly frail patients.

Conclusions and implications

How does our work contribute to the current debate concerning platelet-rich therapy? Very little evidence exists to support any routine clinical applications of platelet-rich therapy. NICE has recommended that its use in the treatment of tendinopathy is limited to research settings.5 To our knowledge, this trial is the first to explore the clinical effectiveness of platelet-rich therapy in osteoporotic bone healing.

A new NICE guideline for the management of fractures of the proximal femur suggests arthroplasty, with a risk of revision of approximately 5%, as opposed to internal fixation for this group of patients with displaced fractures.23 We have been unable to definitively exclude an important treatment effect for platelet-rich therapy, but in the absence of an approximately 20% reduction in the risk of revision surgery following internal fixation with platelet-rich therapy, arthroplasty will remain the standard of care.

Future work might investigate the effectiveness of platelet-rich therapy in different fracture types such as incomplete fractures or those in bone of normal density.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Becky Kearney, Katie McGuinness, Helen Richmond, Kate Dennison, Zoe Buckingham, Troy Douglin, Filo Eales, Gail McCloskey and Catherine Richmond for their assistance in recruitment and data collection during the trial; Philip Roberts, Ceri Jones, Peter Kimani and Steve Drew for their clinical trials and regulatory expertise in the Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring Committee for this trial; and all the patients for their time and effort in participating in this trial. The Trial Steering Committee authorised the release of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: XLG and NP analysed and interpreted the data. XLG and JA managed the recruitment and follow-up of the patients. XLG and NP planned and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was subsequently revised by all authors. All authors participated in the design and management of the study, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript. XLG is the guarantor.

Funding: Support for salaries and consumable costs was received from the Bupa Foundation and Orthopaedic Research UK. Consumables for the GenesisCS Component Concentrating System for the preparation of the platelet-rich plasma were provided at no cost from Gian Medical (Birmingham, UK).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Coventry and Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Additional data are available from the corresponding author (xavier.griffin@warwick.ac.uk).

References

- 1.Hall M, Band P, Meislin R. Platelet-rich plasma: current concepts and application in sports medicine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2010;18:17A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsousou J, Thompson M, Hulley P, et al. The biology of platelet-rich plasma and its application in trauma and orthopaedic surgery: a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91:987–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Intini G. The use of platelet-rich plasma in bone reconstruction therapy. Biomaterials 2009;30:4956–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redler LH, Thompson SA, Hsu SH, et al. Platelet-rich plasma therapy: a systematic literature review and evidence for clinical use. Phys Sportsmed 2011;39:42–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.2008. Interventional procedure overview of autologous blood injection for tendinopathy. NICE interventional procedures guidance.

- 6.Nauth A, Miclau T, Bhandari M, et al. Use of osteobiologics in the management of osteoporotic fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2011;25(Suppl 2):S51–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu-Yao GL, Keller RB, Littenberg B, et al. Outcomes after displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis of one hundred and six published reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker MJ, Raghavan R, Gurusamy K. Incidence of fracture-healing complications after femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;458:175–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker MJ, Khan RJK, Crawford J, et al. Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly. A randomised trial of 455 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:1150–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffin X, Parsons N, Achten J, et al. Warwick Hip Trauma Study: a randomised clinical trial comparing interventions to improve outcomes in internally fixed intracapsular fractures of the proximal femur. Protocol for the WHiT Study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Hip Fracture Database. http://www.nhfd.co.uk/003/hipfractureR.nsf/resourceDisplay?openform (accessed Oct 2012)

- 12.Parker MJ. Garden grading of intracapsular fractures: meaningful or misleading? Injury 1993;24:241–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishra A, Harmon K, Woodall J, et al. Sports medicine applications of platelet rich plasma. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2012;13:1185–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kevy SV, Jacobson MS, Mandle RJ. Analysis of GenesisCS Component Concentrating System: preparation of concentrated platelet product. Cambridge, MA: BioSciences Research Associates Inc, 2006:1–2 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everts PAM, Mahoney B, C Hoffman JJML, et al. Platelet-rich plasma preparation using three devices: implications for platelet activation and platelet growth factor release. Growth Factors 2006;24:165–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin XL, Wallace D, Parsons N, et al. Platelet rich therapies for long bone healing in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;7:CD009496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin XL, Smith CM, Costa ML. The clinical use of platelet-rich plasma in the promotion of bone healing: a systematic review. Injury 2009;40:158–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupont WD, Plummer WD. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials 1990;11:116–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fine J, Gray R. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Team RDC R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cmprsk package. cran.r-project.org/web/packages/cmprsk/ (accessed Sep 2012)

- 23.The Management of Hip Fracture in Adults. 1st edn. 2011. National Clinical Guideline Centre. http://www.ncgc.ac.uklast (accessed Oct 2012) [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.