Abstract

Background:

Migraine is defined as a chronic disabling condition which influences all physical, mental, and social dimensions of quality of life. Some 12-15% of the world population suffers from migraine. The disease is more common among women. The onset, frequency, duration, and severity of migraine attacks may be affected by other predisposing factors including nutrition. Therefore, determining these factors can greatly assist in identification and development of its prevention. Considering the importance of nutrition in maintaining and promoting health and preventing diseases, the present study was conducted to determine the relationship between headaches and nutritional habits (frequency and type of consumed foods) of women suffering from migraine.

Materials and Methods:

This analytical case-control study was conducted on 170 women (in two groups of 85) selected by convenient sampling for the case group and random sampling for the control group. Data collection tool was a 3-section questionnaire including personal information, headache features, and nutritional habits. The questionnaire was completed in an interview performed by the researcher. The data was then analyzed in SPSS using descriptive statistical tests (frequency distribution, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential tests (chi-square, independent t, Mann-Whitney, and Spearman’s correlation tests).

Findings:

The results demonstrated a significant relationship between headache and some food items including proteins, carbohydrates, fat, fruits and vegetables. To be more precise, there were significant relationships between headaches and the frequency of consumption of red meat (p = 0.01), white meat (p = 0.002), cereals (p = 0.0005), vegetables (p = 0.009), fruits (p = 0.0005), salad dressing (p = 0.03), and eggs (p = 0.001). Moreover, a significant relationship existed between headache and type of consumed oil, meat, dairy products, fruits, and vegetables (p < 0.05).

Conclusions:

It is necessary to put more emphasis on the significance of correcting dietary patterns in order to prevent headache attacks and reduce the complications arising from drug consumption in migraine patients. Social and economical efficiency of the patients will thus be enhanced.

Keywords: Migraine, dietary habits, headache, women

INTRODUCTION

Pain is the most common human complaint and headache is the most common type of pain. Although it is annually experienced by three quarters of people, only 5% of them seek medical advice.[1] Headache forms the seventh reason of visits to doctor’s office.[2] It is also responsible for 2–4% of emergency room admissions.[3]

The impact of headache on people’s lives is diverse. As a repetitive and severe event, it results in disability and reduction of quality of life and disorders in interpersonal communications, job productivity, and family life.[1] According to findings of a study, 89% of individuals reported a very low level of job performance during migraine attacks. In addition, headaches caused more than 50% of migraine patients to leave work for 2 days each month.[4] The expenses related to missed working days and medical costs of headaches have been estimated around 50 billion dollars, out of which 17 billion dollars are spent on migraine headaches.[1]

Migraine is the most common headache type in all human societies including Iran. Overall, 12-15% of the world’s population suffer from migraine.[5] Lipton et al. estimated the prevalence of migraines as 18% among females and 6% among males in the U.S.A.[6] In other words, three quarters of the migraine cases occur in women.[7] The higher prevalence of migraine headaches in women during productive years together with bearing social and economic responsibilities has turned migraine into a highly significant issue for women’s health.[8] The prevalence of migraine increases up to the fourth decade of life when it starts to decrease. The highest prevalence of migraine occurs during ages of 25–55 years old which is the time for maximum economic efficiency.[9] People’s behaviors and activities affect their health,[10] i.e. health is negatively influenced by performance such as inappropriate eating habits and lack of enough exercise.[11]

Any changes in lifestyle such as avoiding migraine triggering factors, maintaining regular sleep patterns, and eating and working habits all effectively contribute to migraine prevention.[12] Management of headaches requires a combination of medical and non-medical treatments including having healthy diets, minimum amount of caffeine consumption, and identification and avoidance of the triggering factors. The onset, frequency, duration, and severity of migraine attacks might be affected by the predisposing factors including nutrition.[13] Fatty acids and linoleic and oleic acids also contribute to migraine headache mechanisms. To be more precise, during a migraine attack, an increase occurs in the levels of free fatty acids and blood lipids simultaneous with platelet aggregation, serotonin reduction, and increased levels of prostaglandins. Reducing fatty substances to a maximum of 20 grams per day is usually accompanied by a significant reduction in frequency, severity, and duration of headaches.[14] Determining these factors would thus help identify and develop personal management methods.[13] All social, cultural, environmental, economic, and even political conditions governing different societies are crucially important in nutritional habits of individuals. For example, Americans allocate more than 40% of their food budget to restaurants and fast foods. However, Europeans only allot 5% of this budget to non-homemade foods. It is obvious that the number of daily meals, their amount, ingredients, time, and manner they are served differ in different countries. While having 3 main meals is common across the globe, the value of each meal alters in various countries. It is believed that people’s diets in every country depend on climatic, ecological, and cultural conditions and traditions of each society. This leads to considerable differences in diets across the globe. These days, changes in people’s lifestyle, occupation, and reduced level of physical activity in many societies have endangered their health. Many physicians and nutritionists believe that changes in diet are one of the most effective solutions for curing many diseases.[15,16]

Selecting an appropriate diet plays a crucial role in promoting individual health. Studies have shown that in 7–44% of children and adults suffering from migraine headaches, a specific food or drink may accelerate migraine attacks.[17] Therefore, recognizing the type of food items may be useful in preventing these attacks. Specialists believe that nutrition plays a highly sensitive role in health and prevention and treatment of diseases.[18] Therefore, taking the significance of nutrition and also economic crises in healthcare system into account, an urgent need is felt in order to adopt a general policy to prevent diseases. The present study was hence conducted to determine the relationship between migraine headaches and frequency of consumption of different types of food in order to identify nutritional factors involved in severity and frequency of migraine attacks. Using the findings of this study would result in appropriate measures to moderate and control migraine triggering factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a single-phase analytical case-control study on women affected by headaches who referred to neurology clinics of healthcare centers in Isfahan, Iran. The control group comprised women without headaches who were matched for age, and place of living with the case group. The inclusion criteria for the case group were migraine diagnosis approved by a specialist based on criteria of the International Headache Society, the participant’s awareness of the diagnosis, living in Isfahan, and aging 18250 years old. The inclusion criteria for the control group were the same except for diagnosis of migraine headache. The exclusion criteria were being pregnant or treated with infertility drugs, drug-induced and early menopause, menstrual migraine or any non-migraine headaches, irregular menstruation, allergic diseases, asthma, hypothyroidism, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, digestive disorders (peptic ulcer) and epilepsy, history of sinusoidal or facial surgeries, craniotomy and head trauma, psychotic disorders (anxiety neurosis and depression neurosis), chronic malignant diseases like cancer, all diseases with traumatic physical and mental stresses, and diets for losing or gaining weight. The sample size in this study consisted of 170 people (85 subjects in each group). Individuals in the case group were selected by convenient sampling. Members of the control group were selected by random sampling from the neighbors who lived in a distance of 100 meters from the place of residence of the cases.

Data collection tool was a 3-part questionnaire which was filled out by the researcher in an interview. The first part of the questionnaire included 8 items about personal information, e.g. age, body mass index, marital status, employment status, income amount, and housing status. The second part had 7 questions about the quality of headaches (duration, type, frequency, severity, time of occurrence, and family history of migraines). The third part included 17 items about how they cooked food and the consumed amount of carbohydrates, fat, cereals and grains, various types of meats, dairy products, fruits and vegetables, tea, coffee, cola, chocolate, nuts, canned foods and processed meat products. It was designed based on a 5-point Likert scale (always, often, occasionally, rarely, never). The third part also assessed types of consumed products in 4 main food groups over the past month.

For data analysis, descriptive statistics (frequency distribution, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (chi-square, independent t, Fisher’s exact, and Mann-Whitney tests and Spearman’s correlation) were used in SPSS. P values less than 0.05 were considered as significant.

FINDINGS

Our findings showed that the case and control groups did not have significant differences in terms of age, marital status, education, income, and body mass index. The two groups were thus matched. Most participants in the case (69%) and control groups (89.4%) were housewives since the majority of Iranian women are housewives rather than employed. In fact, based on the report by the Labor Organization, only 13% of women are employed.[19] In addition, 30.6% of the case group and 10.6% of the control group were employed. Chi-square test showed a significant difference in employment status between the two groups (p = 0.041).

According to the results, 76.5% of the case group had migraine headaches without aura while 23.5% had migraine with aura. The mean (standard deviation) of the history of having migraine headaches was 10.13 (9.8) years.

On the basis of Mann-Whitney test, a significant difference existed between the two groups in the frequency of red meat (p = 0.01), white meat (p = 0.002), and cereals (p = 0.0005) consumption.

Canned foods were not consumed by 62.2% of the case group and 51.8% of the control group. However, Mann-Whitney test did not show a significant difference between the two groups in this regard (p = 0.389) and in processed meat products consumption (p = 0.194). The absence of a significant relationship between processed meat products and canned foods consumption and migraine headache might be due to people’s interest in traditional foods and lack of tendency to consume fast foods in Iran.

Moreover, 65.9% of the case group and 75.3% of the control group always used dairy products. The difference in frequency of dairy products consumption between the two groups was not significant according to Mann-Whitney test (p = 0.064). Mann-Whitney test demonstrated that the frequency of vegetables and fruits consumption in the control group was significantly higher than that in the case group (p = 0.009 and p = 0.0005, respectively). While the same test did not reveal a significant statistical difference in terms of frequency of carbohydrate consumption between the case and control groups (p = 0.052), it demonstrated significantly higher frequency of consuming salad dressing and eggs in the control group (p = 0.03 and p = 0.001, respectively). However, significant differences were not seen between the two groups in the frequency of using nuts (p = 0.075), chocolate and cookies (p = 0.391), drinks (p = 0.305), Kalehpacheh (a traditional Iranian food made from head and feet of sheep), and heart, liver, and kidney of sheep (p = 0.251).

According to chi-square test, significant statistical differences existed between the two groups concerning the type of consumed cereals such as beans (p = 0.03), split peas (p = 0.04), and barley (p = 0.02). However, no significant statistical difference was observed between the two groups in terms of consuming garbanzo (p = 0.379), lentil (p = 0.193), mung bean (p = 1.00), fava bean (p = 1), and wheat (p = 0.386) based on chi-square test. In addition, chi-square test did not suggest the two groups to be significantly different in terms of using various types of drinks including coffee (p = 0.221), cola (p = 0.438), alcoholic drinks (p = 0.5), canned fruit juice (p = 0.07), and chocolate milk (p = 0.171). Fisher’s exact test did not show a significant statistical difference concerning tea consumption (p = 0.5). The research results regarding type of nuts showed that 42.5% of the studied subjects in the case group and 62.7% of the control group used walnut. Chi-square test showed a significant statistical difference between the two groups concerning consumption of walnut (p = 0.02). However, there was no significant difference between the case and control groups in consuming sunflower seeds (p = 0.140), peanuts (p = 0.411), potato chips (p = 0.09), pistachios (p = 0.07), almonds (p = 0.07), dried figs (p = 0.467), pumpkin seeds (p = 0.411), and watermelon seeds (p = 0.03) according to chi-square test. Other results about the relationships between food types and migraine headaches are presented in tables 1 to 3.

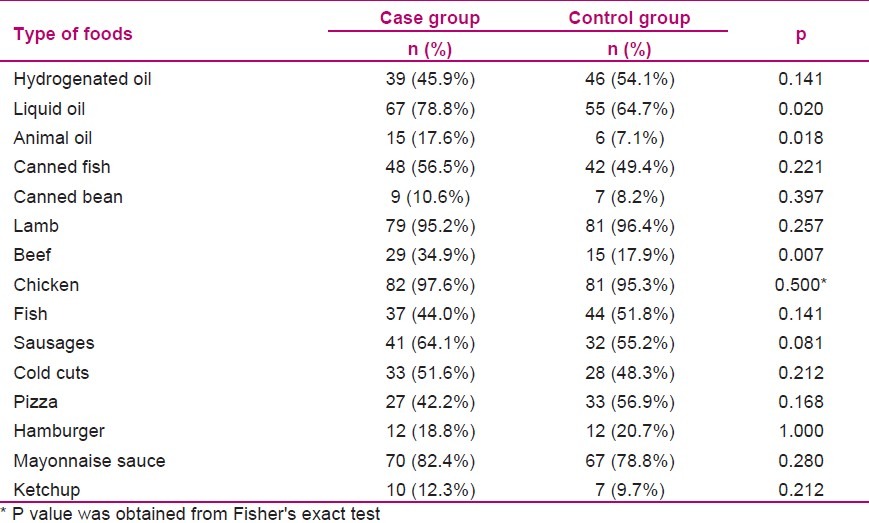

Table 1.

Frequency distribution and comparison of fat type and protein consumed in the case and control groups

Table 3.

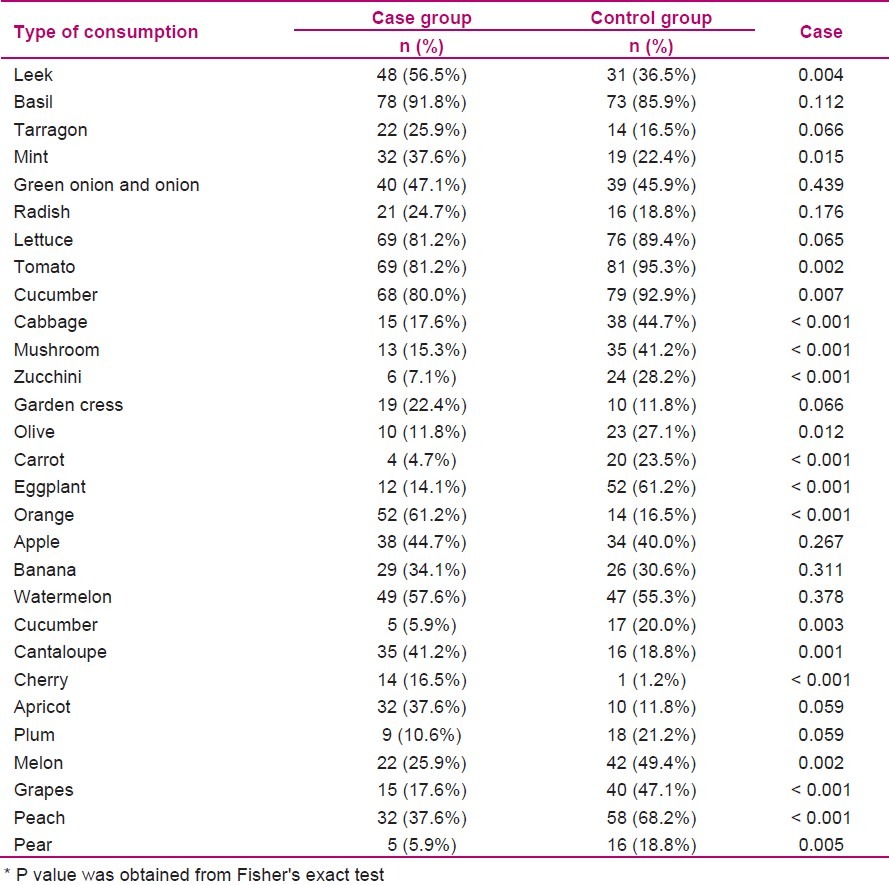

Frequency distribution and comparison of types of consumed vegetables and fruits in the case and control groups

Table 2.

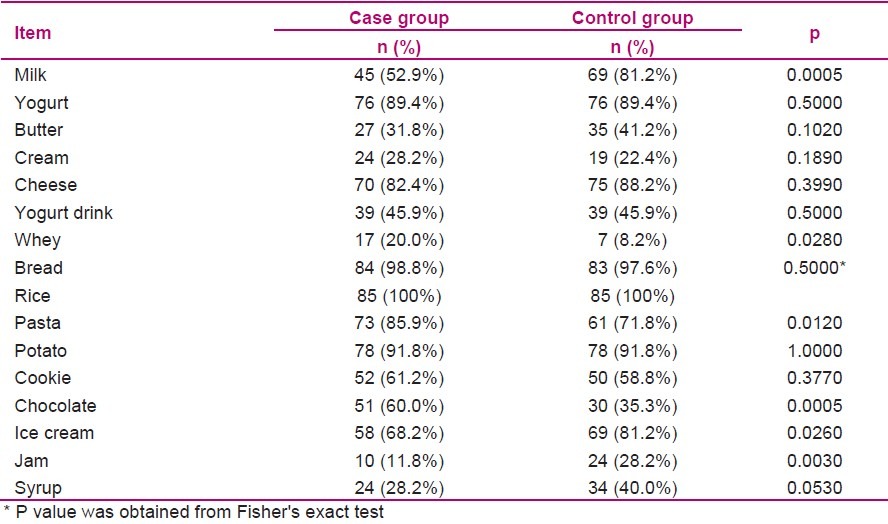

Frequency distribution and comparison of consuming dairy products and carbohydrates in the case and control groups

DISCUSSION

According to the results of this research, there was a significant relationship between employment and migraine headaches. Bingefors and Isacson found that migraine headaches had a strong relationship with both physical and mental stresses at work. In a study on working women, they reported that the level of stress hormones significantly increased after performing a task.[20]

The majority of the case group had migraine without aura. Hickey also reported the majority of migraine patients to suffer from migraine without aura.[1]

Our results showed that the frequency of eating eggs, red meat, white meat, fruits, vegetables, dressings and cereals in the case group was significantly higher than that of the control group, i.e. the control group had better and more balanced nutrition. In addition, liquid oil and animal oil were consumed significantly more by the case group. Bic et al. demonstrated the amount of fatty substances and type of carbohydrates in diets to be related with the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks.[21]

Moreover, in this study, pasta and chocolate consumption in the case group was significantly more than that in the control group. According to a previous study, 75% of the people with migraine headaches considered chocolate (containing phenylethylamine) as a triggering and accelerating factor for migraine attacks.[14]

Consumption of beef was significantly higher among the case group compared to the control group. Jam, syrup, and ice cream were significantly less used in the case group than in the control group. Besides, consumption P value was obtained from Fishers exact test of milk among the case group was significantly lower than in the control group. However, whey consumption in the case group was significantly higher compared to the control group. Studies have shown that consuming some food items, including dairy products, trigger headaches.[22,23].

Regarding vegetables, the case group consumed significantly more leek and mint than the control group. On the other hand, consumption of tomatoes, cabbages, mushrooms, zucchinis, olives, carrots, and eggplants was significantly less frequent in the case group. Similarly, reliable references have introduced tomato as an important trigger of migraine headache. Individuals with migraine are thus highly recommended to avoid eating tomatoes.[5]

The case group consumed cucumber significantly less than the control group which is perhaps due to the cold nature of this fruit. Iranians consider cucumber as having a cold nature and they believe that the probability of headaches will increase by its consumption. As a result, patients with migraine headache refrain from consuming it.

The case group consumed significantly more oranges, cantaloupes and cherries than the control group did. However, consumption of melons, grapes, peaches, and pears was significantly lower in the case group.

Besides, considering types of consumed cereals, the case group consumed significantly less amount of beans and split peas than the control group. In total, the percentage of consumption of various types of grains was lower in the case group in comparison with the control group.

In addition, comparison of the consumed nuts revealed that consumption of walnut and watermelon seeds was significantly lower in the case group. Perhaps, by experience, people found that walnut triggers headaches and also because of the additives used for coloring and preparing watermelon seeds, migraine headache patients observed that they should refrain from them. Since the consumption of some food items are considered allergic, some individuals will have migraines[24] due to increased level of allergy. That is why they attempt to reduce or stop consumption after identifying such agents. In addition, it is probable that over time, people with migraine have directly or indirectly learned about the effects of consumption of food items and the incidence of headaches.

Based on some studies, consumption of some foods including chocolate (containing phenylethylamine), greasy foods, alcoholic drinks especially red wine, artificial sweeteners (aspartame) and garden fruits, citruses and sour fruits, lemon, tomato, onion and green onion, mushroom, dairies and sour yoghurt and cheese (containing tyramine), canned foods, sausages, cold cuts and pizza, hamburger and pork dried with nitrate preservatives, salted fish, mullet, olive, fig, mango, sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, coffee and tea, sodas, yeast, pepper and spices (aspartame), foods containing monosodium glutamate (gelatins, snacks like potato chips or cornflakes, dry roasted peanuts), dressings and cold foods, foods containing nitrate (hot dog, ham, canned meat, smoked foods) triggers headaches.[22–28]

Taking our results into consideration, the hypothesis of the existence of a relationship between eating habits and migraine headaches was confirmed. There was in fact a significant relationship between headaches and consumption of some food items in the four main groups of proteins, carbohydrates, fat, and fruits and vegetables.

Since having awareness and understanding about the risk factors of the disease are considered as important elements in accepting healthy behavior, patients with migraine are required to be educated and hence enabled to correct their nutrition styles and preserve their healthy eating habits which would lead to preventing inappropriate consumption of pills and reduce drug side effects as well as the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks. As a result, social and economical efficiency of the patients will be improved. However, since the present research was conducted on 85 patients due to limited time of the study, more extensive researches are suggested to evaluate the effects of nutrition on frequency and severity of migraine headache attacks among larger populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Finally, we express our gratitude toward all ladies who participated in the research. We are also thankful to the Research Deputy of School of Nursing and Midwifery, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran who assisted us in this research.

Footnotes

Research Article of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, No: 287008

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hickey JV. The Clinical Practice of Neurological and Neurosurgical Nursing. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerinberg DE, Eminoph MJ, Simon RP. In: Aminoph Clinical Neurology 2002. 5th ed. Farhang Bigvand SH, Sarzadeh AE, translators. Tehran: Arjomand Publications; [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowson AJ. Assessing the impact of migraine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2001;17(4):298–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansour Ghanaei F. Common issues in Ambulatory Care. Rasht: Guilan University of Medical Sciences Publications; 1999. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soltan Zadeh A. Neurological and Muscles Diseases. Tehran: Noure Danesh Publications; 2001. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41(7):646–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruining K. Managing migraine: A womens health issue. Sexuality, Reproduction and Menopause. 2004;2(4):209–12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unger J, Cady RK, Farmer-Cady K. Part Three; Understanding migraine: strategies for prevention. Emergency Medicine. 2003;35(10):39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipton RB, Bigal ME. The epidemiology of migraine. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 1):3S–10S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pour Eslami M, Sarmast H, translators. World Health Organization. Health promotion terminology. Tehran: Tehran University Press; 1999. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potter PA, Perry AG. Fundamentals of nursing. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adelman JU, Adelman RD. Current options for the prevention and treatment of migraine. Clin Ther. 2001;23(6):772–88. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mannix LK. Relieving migraine pain: sorting through the options. (16).Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(1):8–4. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.70.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millichap JG, Yee MM. The diet factor in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;28(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(02)00466-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller I, Lang T. Food-based dietary guidelines and implementation: lessons from four countries--Chile, Germany, New Zealand and South Africa. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(8):867–74. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis D W, Yonker M, Winner P. The prophylactic treatment of pediatric migrain. Pediatic Annals. 2005;34(6):449–60. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20050601-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mansheei GR. Health Psychology. Isfahan: Ghazal Publications; 1997. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadri Abyaneh F. Employment and culture of Women, Shiite Ladies Monthly [Online] 2005. Available from: URL: www.ensani.ir/fa/content/148881/default.aspx/

- 20.Bingefors K, Isacson D. Epidemiology, co-morbidity, and impact on health-related quality of life of self-reported headache and musculoskeletal pain-a gender perspective. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(5):435–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bic Z, Blix GG, Hopp HP, Leslie FM, Schell MJ. The influence of a low-fat diet on incidence and severity of migraine headaches. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8(5):623–30. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maville JA, Huerta CG. Health Promotion in Nursing. New York: Delmar; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans RW, Mathew NT. Handbook of Headache. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghorbani A. Diagnosis of headache and new news about treatment. Isfahan: Chahar Bagh Publications; 2002. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson M. In: Migraine and different types of headaches. Hemmatkhah F, translator. Tehran: Asr-e-Ketab Publications; 2003. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams CE. Migraine headache: Triggers and treatments [Online] 2005. Available from: URL: http://www.ealingwell.com/librarymigraines/article/

- 27.Ameli J. Migraine Headaches. Scientific Educational Monthly of Medical Faculty of Baghiatallah Medical Sciences University. 2003;8(58–59):56–64. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerechkof VE. In: Headache Prevention and Treatment. Zarei M, Mizbani M, translators. Isfahan: Senoubar Publications; 1999. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]