Abstract

Background:

Nurses and other members of health care team provide mental patients with health services through interprofessional collaboration which is a main strategy to improve health services. Nevertheless, many difficulties are evidently influencing interprofessional collaboration in Iranian context. This paper presented the results of a study aimed to explore the context.

Materials and Methods:

A qualitative study was conducted using in-depth interviews to collect data from 20 health professionals and 4 clients or their family members who were selected purposefully from the health centers affiliated with Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Themes were identified using latent qualitative content analysis. Trustworthiness of the study was supported considering auditability, neutrality, consistency and transferability. The study lasted from 2010 to 2011.

Findings:

Some important challenges were identified as protecting professional territory, medical oriented approach and teamwork deficits. They were all under a main theme emphasizing professionals’ divergent views. It could shed insight into underlying causes of collaboration gaps among nurses and other health professionals.

Conclusions:

The three introduced themes implied difficulties mainly related to divergences among health professionals. Moreover, the difficulties revealed the need for training chiefly to improve their convergent shared views and approaches. Therefore, it is worthwhile to suggest interprofessional education for nurses and other professionals with special attention to improving interpersonal skills as well as mental health need-based services.

Keywords: Mental health services, interprofessional collaboration, challenges, Iran

INTRODUCTION

Health systems have undergone many challenges in recent years. Awareness promotion among the community, facing with increasing, more complicated needs of the population and shifting attention towards Mental Health Services (MHS) as a necessary part of health services have inspired nurses and other health professionals to adopt initiatives to improve quality of health services.[1]

Encountering complexities and bulk of problems in health systems, particularly in MHSs, have led governments, politicians and health system managers of many countries towards adopting collaborative initiatives.[2–6] Therefore, interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is increasingly considered as one of the main goals and strategies of health services.[7] IPC is a process through which professionals from different professions work together as a team in order to achieve a shared goal (improving health care).[8] On one hand, IPC can help improve services,[9] and on the other, it can provide opportunities to improve health services as well as health professionals.[10–12] Nurses are amongst the main mental health team members who benefit from IPC in terms of improving both nursing services and their own professional competencies.

Although the concept of interprofessional activities is identified in some aspects mainly in medical education context in Iran,[13,14] the Iranian health system suffers from lack of a defined model of IPC in MHS. Vast endeavors have been done in order to create an integrated MHS system and define collaboration pathways between nurses and other health professionals. The first attempts were performed in 1985 when a national program was planned to integrate mental health in the primary health care system. The program was based on a referral system in which some opportunities to develop interprofessional collaborative relationships were made. Thus, the health professionals used to refer the clients interprofessionally under certain conditions.[15] Most collaborative activities are still carried out through a referral system.

Evidence showed that poor IPC in MHS resulted in fragmented services within which the clients failed to find suitable services. In such situation, both the clients and service providers feel unsuccessful.[4] Despite the importance of IPC in MHS, review of literature revealed various challenges such as ambiguity in concept and practical evidences of IPC,[3] organizational factors,[16,17] profession related challenges,[18] health professionals’ divergent views and attitudes[19–21] and poor health service management.[22] Based on the authors’ experiences and some previous studies, the current health system, particularly MHS, is suffering from collaboration gaps among health professionals. Therefore, many researchers have attempted to identify and describe IPC challenges.[4,21,23–25]

In addition, published documents about Iranian mental health system have identified a variety of challenges related to either MHS or the activities of health professionals in the health system. Some examples are challenges related to underutilization of MHS in needy population,[26] health professionals’ interpersonal relationships[27] (mainly gaps in physician-nurse relationships),[28] inconsistencies in nursing profession,[29] insufficient support for health services such as insufficient insurance coverage.[30] Nevertheless, none of the Iranian documented evidences have related these challenges to the concept of IPC. In other words, the concept of IPC in health system, particularly in MHS, is new. Bulks of previous studies investigating challenges of IPC in MHS are based on quantitative methods using predetermined structures and tools.[21,31] However, the complex and context-dependent nature of IPC,[7,32] as well as complexities in the MHS itself,[33] implies the use of a qualitative approach to cover such issue.[34] Therefore, the necessity of a study in order to explore and describe challenges of IPC in MHS is evident. Since there are still no appropriate tools for assessing IPC in the study context, conducting a qualitative study could be helpful. Thus, this study aimed to explore and describe challenges of IPC in MHS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study used qualitative content analysis since it is an appropriate method to explore complex social phenomena[35] such as the IPC.[7,32] This paper presents some findings of a larger study investigating the structure of IPC in the Iranian MHS. The study employed sequential mixed (qualitative-quantitative) methods to explore the structure of IPC in MHS. It lasted from 2009 to 2010. The study population consisted of health professionals from different professions and clients or their family members from health centers affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Including criteria for both nurses and other health professionals were being employed in the health system. Subjects were included if they were willing to participate in the study. The study began in 2009 and lasted until 2011.

Participants were selected purposefully but entered the study voluntarily. After following some official procedures and obtaining a written permission, the researcher attended health centers where the study participants were accessible. Interviews were organized at times and places agreed by each participant. Then, the researcher met each participant to briefly explain about the study goals, method of conducting the study and the participant’s role in the study. Subjects signed informed consents before beginning the interviews. Data was gathered mainly from professionals rather than the clients. The clients were only included to clarify some ambiguities and controversies raised through interviews with professionals. The participants were asked for their permission to record the interviews and they were assured about confidentiality, anonymity and freedom to quit the study.

The interviews were carried out in a private place, mainly workplace (health centers). Data was collected through in-depth interviews using a few leading questions. Samples of leading questions used for professionals were “What is your experiences of IPC?” and “What difficulties have you faced during your interprofessional relationships and collaborative activities?”. The questions were subsequently modified based on points and topics raised during the interviews. Each interview lasted about half to one hour. Data saturation was the criteria for deciding about sampling adequacy.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis were conducted simultaneously. Each interview was transcribed verbatim and analyzed before the next interview took place. A qualitative latent content analysis was used for transcriptions of the interviews to discover the underlying themes.[36] Circular process of understanding was used to move towards an interpretative analysis of the underlying meaning. The interpretation process was started by reviewing transcripts for several times. It led to gain a sense of the whole and was helpful in obtaining a preliminary understanding of the phenomenon under investigation and its context and grasping the fundamental features of the transcribed information. The statements that fitted into a specific theme were identified and transformed into meaningful units. They were then coded into themes and subthemes. As a result, codes conceptually similar in meaning and nature were classified into the same category. The last step was interpretation of the transcribed information as a whole, through which the understandings gained from separate interviews were blended to shape a comprehensive understanding.[37]

In order to support the study rigor, trustworthiness, acceptability and neutrality, parts of the transcripts and findings were shown to the participants to check out whether they were consistent with their real experiences and perceptions. Researchers selected participants from different professional and working background in order to ensure maximum variation leading to real and valid results. The clients or their family members entered the study to help the achievement of reliable and consistent data. Coding and analysis processes were peer checked with two independent researchers. Finally, the researchers tried to avoid prejudice or prejudgments about the phenomenon under the study in all stages from data collection to interpretation.[38]

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Moreover, written permissions were signed chiefs of hospitals and other health centers. All subjects were informed about the purpose and procedure of the study before participating. They also provided informed consents. The anonymity was definitely warranted. The raw data including transcripts was stored securely and was accessible only for the research team.

FINDINGS

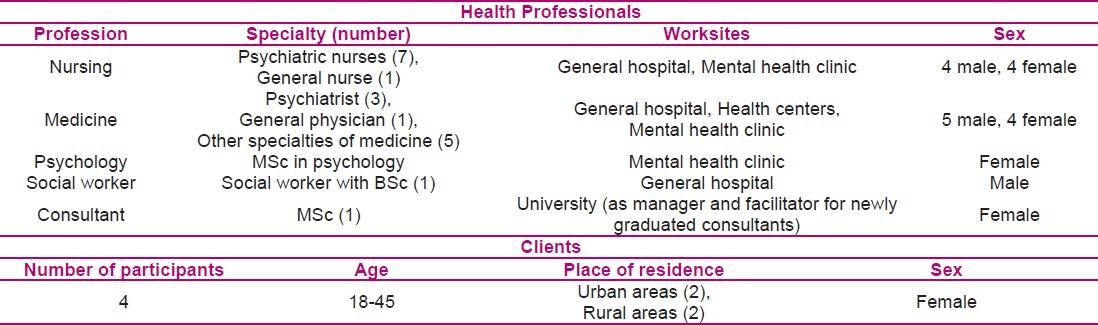

The study participants consisted of 20 professionals (including 9 physicians, 8 nurses, 1 psychologist, 1 social worker and 1 consultant) and 4 clients (including patients or their family members). Some demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the studied individuals

Following analysis of the qualitative data in the main study, few headings such as practice territories, readiness for IPC, context, collaboration as a pathway of service delivery and management were identified. Few themes and several subthemes were categorized under each heading. These headings and related themes were linked together to draw a whole picture of IPC structure in the Iranian MHS system. Being dependent on the whole picture of the IPC structure, each emerged theme depicted some challenges of the IPC. This paper could identify three important themes under one main heading that emphasizes divergent views and approaches about health care related issues among the professionals. These themes were “Protecting professional territory”, “Medical oriented approach” and “Teamwork deficits”.

Theme 1: Protecting professional territory

Each professional has a collection of roles, authorities and talents that root in their discipline backgrounds. These traits are considered as “professional territory” in the present study. Based on the participants’ experiences, health professionals have some common traits such as a shared goal (i.e. providing health services), shared values (i.e. improving health in community), and a shared working background (i.e. patient education) that provide them with shared opportunities. For example, nurses work for the same clients and they reach the same information as the other professionals do.

On the other hand, closeness and commonalities among health professionals may deliver opportunities for competition. Participants’ experiences showed that some professionals are worried about their professional territories to be exploited by other professions. This challenge was identified as a subtheme called “Vulnerable territories”. This is the reason why some professionals have considered common traits as threatening rather than shared opportunities:

“Sometimes professionals keep a patient whose problem is not related to their specialty. For example, a neurologist could treat a convulsion case as it is consistent with his/her specialty. However, a client with depression does not … does not fall in his/her work span; but I saw that he/she keeps the client and did not refer.” (No. 1, a psychiatrist).

It is particularly perceived by psychiatric nurses whose roles are overlapped by some other professionals such as psychiatrists and psychologists:

“For example, if we are supposed to deliver MHS to specific clients, our professional specific roles and scope of activities must be defined clearly.” (No. 18, a psychiatric nurse)

Professionals need to have definite working and professional boundaries in which they can work without fear of outsider offenders. Based on the study findings, “Hidden territories”, a subtheme to the main theme “Protecting professional territory”, implies that health professionals perceived indefinite territories as threatening since it may pave the way for outsiders to meddle. It is evident in a psychiatrist’s quote who said:

“Common boundaries are indefinite; it is not clarified that where the green, yellow and red lines are. For example, to what extent are we allowed to go forward without a hitch and where are we not allowed to go ….” (No. 1, a psychiatrist)

Based on the participants’ experiences, deficits in construction of interprofessional teams, being worried about professional territories and competition to reap hidden territories, all rooted in the inadequate knowledge of professionals about other professions. For instance, a psychiatric nurse disclosed his worry as follows:

“The dominant approach in health care, particularly in MHS, is not team-based. Nowhere in the health system, or the MHS, is real teamwork. Now, our inadequate knowledge of other professions and physicians’ inadequate knowledge of our profession, along with some competitions, raise more complex situations.” (No. 12)

Professionals’ perceptions of these challenges, which were categorized under two subthemes, revealed their feelings of uncertainty and worry about hurting their profession due to the IPC.

Theme 2: Medical oriented approach

“Medical oriented approach” depicted a situation within which professionals treat the clients as biological entities, i.e. they pay all their attention to meet the clients’ biological deficits and needs. Findings showed that health professionals who follow such an approach may neglect the clients’ non-biological (i.e. psychosocial) needs and problems. This challenge was identified under the subtheme of “One-dimensional human”. Based on our findings, after adopting such an approach, health professionals find themselves as necessary and “adequate” for delivering health services. Therefore, they neglect help from other professionals, particularly in other professions. This is especially inconsistent with paradigm of nurses whose approach is holistic rather than one-dimensional. Some nurses argued that such divergences have led them to being detached from other professionals. A psychiatric nurse said:

“Some (physicians) are in belief that chemistry is the only thing that could cure. Some of them don’t trust psychotherapy; so they don’t like to refer the clients to a psychiatric nurse or psychologist … it sometimes hinders collaboration” (No. 15, a psychiatric nurse)

Based on the participants’ experiences, more problems raised when some professionals treated the patients as medical cases only worth studying rather than a human who needed health services. This finding, identified under the subtheme of “Illness-centeredness”, depicted another challenge that hindered health professionals from seeking help from other professionals. A medicine specialist said:

“We are often looking for attractive cases; many physicians think like this, no matter this attractive case is a human who has feelings. The only important thing is that for example this is a rare case. We sometimes say that bed number 8 is a wonderful rare case …” (No. 11)

Based on the study findings, a part of challenges in IPC is derived from inadequate attention to the clients’ needs and problems. Having a one-dimensional approach to the patients and paying attention to diseases instead of all biopsychosocial aspects of clients may lead professionals to adopt a uni-professional approach through which they hardly ever need to use experiences of other professions.

Theme 3: Teamwork deficits

Teamwork is an important strategy in the IPC through which the professionals enter collaborative activities. Professionals in this study emphasized on the importance of teamwork skills to develop IPC. Based on the study findings, some gaps in the IPC are resulted from teamwork deficits originated from poor communication among professionals. This challenge was depicted under the subtheme of “Poor interprofessional communication”.

Some nurses argued that the poor interprofessional communication particularly with physicians have led to poor IPC in the study context. A quote from a nurse supports this view:

“Some professionals are reluctant to respond; so other professionals cannot understand what they mean… Consequently, they fail to share their information because they feel uncertain and cannot trust anymore.” (No. 5)

Inadequate insight to the necessity of teamwork along with poor team functions have made team context to be an unfavorable and unsafe environment for IPC. The researchers suggested the subtheme of “Poor teamwork culture” to describe such challenge that has hindered development of IPC in the MHS system. Some professionals argued that poor relationships among team members were due to their insufficient awareness about the necessity and importance as well as goals of teamwork. For example, a physician said:

“Well, because they are not convinced; they are not acquainted about benefits and goals of shared work. For example, when a nurse comes to an interprofessional round with a psychiatrist, it is nothing clear but benefits for the nurse. It is not clear what topics are supposed to be dealt with through these relationships.” (No. 1)

Some participants believed that teamwork skills are a part of community culture. They therefore argued that training plans should be directed towards preparing the whole community rather than health professionals who are a subgroup of the community. A participant said:

“Basic infrastructures should be prepared. I mean willingness to work in a team is not created overnight. It needs primary training that should be provided for the students both in primary school and later in universities.” (No. 10, a social medicine specialist).

DISCUSSION

IPC is identified as a suitable strategy to overcome complexities of MHS. Since evidences revealed various challenges to IPC in MHS, particularly gaps among nursing and other professions, the present study aimed to explore and describe the IPC challenges in the study context. The study findings emphasized that challenges were often human-related, i.e. they originated from nurses and other professionals’ divergent views and approaches. This is a finding worth to be considered in future IPC programs in MHS.

The theme “Protecting professional territory” depicted an aspect of IPC challenge and described health professionals who feel too devoted to their profession and linked their personal identity to their profession. They considered professional territory as a boundary that separated insiders from outsiders. Since breaking the ancient boundaries and structures is a prerequisite for IPC, it is seen as a potential threat followed by defensive reactions from members of each single profession.[12] Since each health profession has a strict control over its knowledge and skills, professionals cannot stand any interfere or evaluation from the outside[39] which is in contrast with IPC.

Members of different professions often behave through various conceptual frameworks and knowledge which results in different perceptions of the patients’ mental health needs and consequently difficulties in communication and shared decision making.[21] Professions also may perceive the outsider professions as offenders and therefore refuse collaboration. This is the reason why problems related to multiprofessional health groups have been longstanding.[18] Evidence showed that despite some conceptual complexities, the theoretical concept of IPC in health system is more developed than it does in practice. For instance, although a real collaborative care in MHS is not supposed to be restricted to policies for a single profession, this is what practically happens.[3]

Health professionals need to restructure their own professional frameworks to match new caring models, new roles, responsibilities and relationships in order to overcome IPC challenges. They need to have a new range of skills and competencies in order to be able to meet their own complex roles in the current MHS system. Nurses, as well as other professionals, should be prepared to work in multiprofessional health settings.[40]

The theme “Teamwork deficits” introduced another challenge of IPC in the study context. When health care team consists of professionals with different backgrounds and views, teamwork becomes more difficult. At the same time, the necessity of higher levels of skills becomes more prominent. In fact, the spirit of interprofessional team is identifying, integrating and applying skills and views from different professions in order to achieve a common goal.[22] However, nurses and other health professionals’ worries about losing identity, role ambiguity and interprofessional conflicts are constant problems. Such worries were also approved by our findings similar to some other studies. For instance, a study assessed the roles of nurses in MHS provided to children and adolescents. It pointed out that nurses may be unclear about their own professional specific roles in such teams.[41] Nevertheless, findings from another study showed that professionals in multidisciplinary teams in MHS system are able to keep their own specific roles besides common core tasks.[22] However, this challenge is so extensive that even some studies introduced conflict as endemic in the IPC. Conflict also rises from different and somehow contrary demands originated from educational backgrounds and home settings of health professionals as well as fluctuating and uncertain policies in the health systems. Misconceptions and conflicts may increase if professionals do not perceive the differences.[20] Literature emphasizes the necessity of problem solving strategies in order to manage conflicts and overcome this challenge. Some researchers believe that “managed conflict” is an important catalyst for learning, development, creative function and increasing trust.[12] When professionals think about collaborative work, they need to consider the best ways to integrate their different views. It is also necessary to converge different experiences and skills in order to improve client-centered services.[42] Although teamwork-related challenges are mainly derived from differences between professionals, some experts optimistically have argued that more diversity would result in more potential for decision in complex situations.[19,42]

The last theme, “Medical oriented approach”, implied another human-related challenge of IPC in MHS. In the present study, medical oriented approach meant caring for and treatment of clients in order to fulfill their physiological deficits. In the other words, a patient was seen as an illness case rather than a whole human. Therefore, the client’s mental health would be ignored. Health related literature has identified this challenge as “medicalization”.[43,44]

In contrast with some other divisions in health and medicine, the science of mental health care believes that health problems and disorders are multi-factorial and influenced by biopsychosocial and cultural aspects. Mental health scientists suggest that potentials and skills of various professions should be used to affect all these aspects.[22] It is why the medical oriented approach ignores the necessity of IPC. This finding emphasized the importance of attitudes and knowledge of health professionals towards all aspects of patients’ health instead of only physical health.

In brief, our results highlighted some challenges to IPC and exposed the necessity of training programs for nurses and other health professionals to overcome divergences existing among them.

Study limitations

The subjective nature of data collection and the small number of the participants limited the generalization of the findings. Moreover, selecting the participants from inpatient settings, rather than community settings, led to findings best interpretable in the same settings.

CONCLUSION

“Divergences” in views of health professionals, verified by the literature, seems to be related to the different natures of professions.[19] Therefore, a common training field is recommended to improve these convergent shared views and approaches. In fact, interprofessional education[13,14] with special attention to improving interpersonal and interprofessional skills is of utmost importance. Since nurses are recognized as main members of every mental health team, overcoming the identified challenges may be helpful to improve their collaboration with other health professionals. Further research is suggested to examine the effects of each challenge in nurses’ relationships with other professionals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank all participants who kindly assisted us to conduct interviews.

Footnotes

Research Article of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, No: 389116

Source of Support: This study was funded by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaboury I, Bujold M, Boon H, Moher D. Interprofessional collaboration within Canadian integrative healthcare clinics: Key components. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(5):707–15. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kingdon DG. Interprofessional collaboration in mental health. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 1992;6(2):141–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keleher H. Community-based Shared Mental Health Care: A Model of Collaboration? Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2011;12(2):90–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glasby J, Lester H. Cases for change in mental health: partnership working in mental health services. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(1):7–16. doi: 10.1080/13561820410001639316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pomerantz A, Cole BH, Watts BV, Weeks WB. Improving efficiency and access to mental health care: combining integrated care and advanced access. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(6):546–51. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odegard A, Strype J. Perceptions of interprofessional collaboration within child mental health care in Norway. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(3):286–96. doi: 10.1080/13561820902739981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin RL, Beaulieu MD. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core concepts and theoretical frameworks. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):116–31. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broers T, Poth C, Medves J. What’s in a Word. Understanding “Interprofessional Collaboration” from the Students’ Perspective? Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education. 2009;1(1):3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gannon-Leary P, Baines S, Wilson R. Collaboration and partnership: a review and reflections on a national project to join up local services in England. J Interprof Care. 2006;20(6):665–74. doi: 10.1080/13561820600890235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fichtner CG, Hardy D, Patel M, Stout CE, Simpatico TA, Dove H, et al. A self-assessment program for multidisciplinary mental health teams. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(10):1352–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.10.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferies H, Chan KK. Multidisciplinary team working: is it both holistic and effective. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14(2):210–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.014201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawson H. The logic of collaboration in education and the human services. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(3):225–37. doi: 10.1080/13561820410001731278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irajpour A. Inter-professional education: a reflection on education of health disciplines. Iranian Journal of Medical Education. 2010;10(4):451–62. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irajpour A, Barr H, Abedi H, Salehi S, Changiz T. Shared learning in medical science education in the Islamic Republic of Iran: an investigation. J Interprof Care. 2010;24(2):139–49. doi: 10.1080/13561820902886246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohit A. A Brief Overview of the Development of Mental Health in Iran, Present Challenges and the Road Ahead. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences (IJPBS) 2009;3(2):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callaly T, Fletcher A. Providing integrated mental health services: a policy and management perspective. Australas Psychiatry. 2005;13(4):351–6. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2005.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darlington YA, Feeney JA, Rixon KM. Complexity, conflict and uncertainty: Issues in collaboration between child protection and mental health services. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26(12):1175–92. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers T. Managing in the interprofessional environment: a theory of action perspective. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(3):239–49. doi: 10.1080/13561820410001731287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner DB. Ten lessons in collaboration. Online J Issues Nurs. 2005;10(1):2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohr WK. Psychiatric-Mental Health Nursing: Evidence-Based Concepts, Skills and Practices. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darlington Y, Feeney JA. Collaboration between mental health and child protection services: Professionals’ perceptions of best practice. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30(2):187–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen A, Callaly T. Interdisciplinary teamwork and leadership: issues for psychiatrists. Australas Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):234–40. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2005.02195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villeneau L, Hill RG, Hancock M, Wolf J. Establishing process indicators for joint working in mental health: rationale and results from a national survey. J Interprof Care. 2001;15(4):329–40. doi: 10.1080/13561820120080463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brems C, Johnson ME, Warner TD, Roberts LW. Barriers to healthcare as reported by rural and urban interprofessional providers. J Interprof Care. 2006;20(2):105–18. doi: 10.1080/13561820600622208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purden M. Cultural considerations in interprofessional education and practice. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):224–34. doi: 10.1080/13561820500083238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghanizadeh A, Arkan N, Mohammadi MR, Ghanizadeh-Zarchi MA, Ahmadi J. Frequency of and barriers to utilization of mental health services in an Iranian population. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14(2):438–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irajpour A. Development of shared learning in medical sciences education in Islamic Republic of Iran [PhD Thesis] Isfahan: School of Nursing and Midwifery, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehrabi M. A sociological study on interprofessional relationship between doctor and nurse [Online] 2011. [cited 25 January 2011] Available from: URL: http://www.salamatiran.com/NSite/FullStory/?Id=32815&type=3 .

- 29.Nasrabadi AN, Lipson JG, Emami A. Professional nursing in Iran: an overview of its historical and sociocultural framework. J Prof Nurs. 2004;20(6):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehrdad R. Health System in Iran. JMAJ. 2009;52(1):69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimitriadou A. Interprofessional collaboration and collaboration among nursing staff members in Northern Greece. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2008;1(3):140–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.El AW, Phillips CJ, Hammick M. Collaboration and partnerships: developing the evidence base. Health Soc Care Community. 2001;9(4):215–27. doi: 10.1046/j.0966-0410.2001.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gask L. Overt and covert barriers to the integration of primary and specialist mental health care. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(8):1785–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeves S, Lewin S, Espin S, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional Teamwork for Health and Social Care. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohlbacher F. The Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in Case Study Research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2005;7(1) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohlbacher F. The Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in Case Study Research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2006;7(1) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Speziale HS, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing: advancing the humanistic imperative. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldwin DC. Territoriality and power in the health professions. J Interprof Care. 2007;21(Suppl 1):97–107. doi: 10.1080/13561820701472651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lloyd C, King R, McKenna K. Generic versus specialist clinical work roles of occupational therapists and social workers in mental health. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(3):119–24. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldwin L. The nursing role in out-patient child and adolescent mental health services. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(4):520–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valios N. Interprofessional and inter-agency collaboration Community Care [Online] 2009. [cited 2009 Aug 3]; Available from: URL: www.communitycare.co.uk/

- 43.Lantz PM, Lichtenstein RL, Pollack HA. Health policy approaches to population health: the limits of medicalization. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(5):1253–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Navarro V. The World Health Report 2000: can health care systems be compared using a single measure of performance. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(1):31, 33–34. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]