Abstract

The association between physical activity, potential intermediate biomarkers and lung cancer risk was investigated in a study of 230 cases and 648 controls nested within the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer and Nutrition. Data on white blood cell aromatic-DNA adducts by 32P-postlabeling and glutathione (GSH) in red blood cells were available from a subset of cases and controls. Compared to the first quartile, the fourth quartile of recreational physical activity was associated with lower lung cancer risk [odds ratio=0.56 (0.35–0.90)], higher GSH levels [+1.87 micro mole GSH/gram haemoglobin, p=0.04] but not with the presence of high levels of adducts [odds ratio=1.05 (0.38–2.86)]. Despite being associated with recreational physical activity, in these small scale pilot analyses GSH levels were not associated with lung cancer risk, [odds ratio=0.95 (0.84 – 1.07) per unit increase in glutathione levels]. Household and occupational activity was not associated with lung cancer risk or biomarker levels.

Keywords: physical activity, lung cancer, biomarkers, molecular epidemiology

Introduction

In 2006 in Europe lung cancer represented 12.1 percent (386,300 cases) of all incident cancer and it was the leading cause of cancer death (Ferlay et al. 2007). Several studies have suggested that increased physical activity is protective against lung cancer (Kubik et al. 2007; Lee and Paffenbarger 1994; Lee et al. 1999; Leitzmann et al. 2009; Mao et al. 2003; Severson et al. 1989; Sinner et al. 2006; Sprague et al. 2008; Thune and Lund 1997; Yun et al. 2008). Since there are few prevention programs for ex-smokers, the most interesting data from a public health perspective are on associations between physical activity among ex-smokers and future lung cancer risk. Two reports from the Harvard Alumni Study saw reductions in lung cancer risk among physically active subjects who were non- and ex-smokers while two studies have found physical activity to be protective among ex-smokers but not non-smokers (Lee and Paffenbarger 1994; Lee et al. 1999; Leitzmann et al. 2009; Sinner et al. 2006). However, in a hospital based case-control study in Prague, physical activity was not associated with lung cancer risk in non-smokers and long term ex-smokers (Kubik et al. 2007).

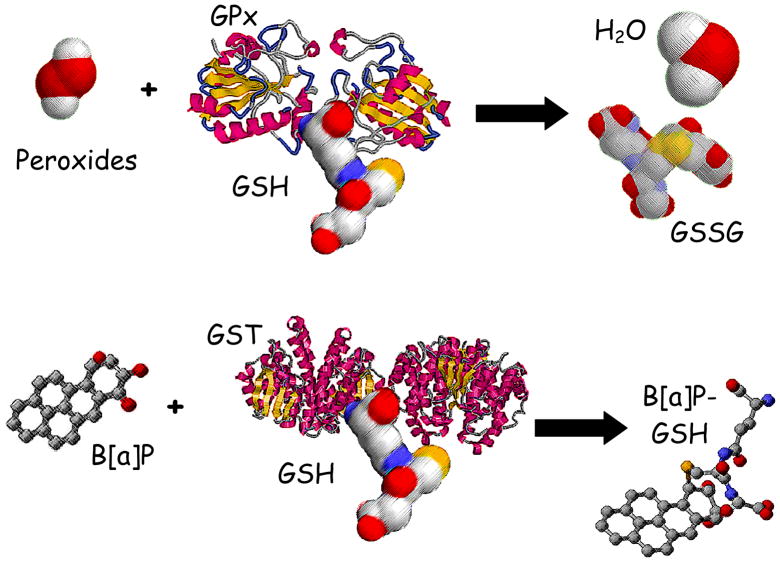

It has been recommended that biomarker studies be conducted of possible mechanisms through which physical activity might exert protective effects on cancer outcomes (Hoffman-Goetz et al. 1998; McTiernan et al. 1998; Thune I 2000). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the observed protective effects of physical activity, including increased endogenous antioxidant defenses which are particularly relevant for ex-smokers, as oxidative stress promotes tumor growth (Cerutti 1985; Frenkel 1992; Rundle 2005). Glutathione (GSH) is an endogenous antioxidant found in exceptionally high concentrations in respiratory tract lining fluid and is a cofactor in the glutathione peroxidase mediated detoxification of reactive oxygen species and is a cofactor in the glutathione S-transferase mediated detoxification of carcinogens [see Figure 1] (Bartsch et al. 1991; Boehme et al. 1992; Cantin et al. 1987; Jernstrom et al. 1982; Kelly 1999). Glutathione levels have also been shown to be positively associated with increased moderate intensity physical activity and to increase with exercise training (Evelo et al. 1992; Karolkiewicz et al. 2003; Michelet et al. 1995; Robertson et al. 1991; Rundle et al. 2005a). As such, activity induced increases in GSH have been proposed as a mechanism through which physical activity might influence cancer risk (Rundle et al. 2005a). Additionally several studies have investigated whether carcinogen DNA adducts, typically bulky-aromatic adducts thought to be derived from cigarette smoke, are associated with lung cancer risk (Bak et al. 2006; Peluso et al. 2005b; Tang et al. 2001; Tang et al. 1998; Veglia et al. 2008; Veglia et al. 2003). In general positive associations between increased adduct levels and lung cancer risk have been observed among current smokers (Veglia et al. 2008; Veglia et al. 2003), however in one study the strongest association was found among never-smokers (Peluso et al. 2005b). Physical activity has been associated with increases in enzymatic systems that detoxify chemical carcinogens and protect the lungs (Duncan et al. 1997; Rundle et al. 2005a) suggesting another mechanism through which physical activity may be protective.

Figure 1.

illustrates pathways through which glutathione is hypothesized to reduce lung cancer risk. Glutathione is a co-factor in the glutathione peroxidase (GPx) mediated detoxification of hydroperoxides and is oxidized to glutathione disulfide (GSSG). Additionally, glutathione is a conjugating group for the glutathione transferase (GST) mediated detoxification of chemical carcinogens, here illustrated with glutathione being conjugated to benzo[a]pyrene to create a water soluble metabolite.

An important issue arises when analyzing data from recent ex-smokers; the decision to quit smoking may be linked to changes in physical activity and health status. Several studies of smokers have shown that increased stage of change for smoking cessation is associated with increased physical activity and with stage of change for exercise adoption and that readiness for physical activity is inversely associated with cigarettes smoked per day (Boyle et al. 2000; Doherty et al. 1998; Emmons et al. 1994; Garrett et al. 2004). In some people smoking cessation may be associated with the adoption of healthier lifestyle practices (Kawada 2004; Tang et al. 1997). However, many smokers quit smoking because of declining health which may also impact physical activity patterns in the years around the time of smoking cessation (Fishman et al. 2003; Halpern and Warner 1994; Joseph et al. 2005; Twardella et al. 2006; Wagner et al. 1995). Thus among some recent quitters health status may be causally associated with smoking status, and with past smoking behavior and recent physical activity patterns. In other recent quitters, the decision to quit smoking may be associated with the decision to adopt exercise and both decisions may be associated with the extent of past daily smoking. Such patterns of variables that may simultaneously act with mediating and confounding effects may bias the results of analyses and such a bias cannot be addressed by standard multivariate approaches (Robins 1989; Robins et al. 2000).

Analyses of lung cancer risk and physical activity have been conducted in the overall European Prospective Investigation of Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort and no overall protective effect was observed (Steindorf et al. 2006). Here we focus on never-smokers and individuals who quit smoking ten or more years before entering the cohort, thus minimizing the potential for smoking cessation in recent quitters being associated with changes in lifestyle that might bias study results. This issue has not been previously addressed in studies of physical activity and lung cancer. We also incorporate biomarker analyses into an epidemiologic study of physical activity and cancer and report on pilot analyses of physical activity, GSH levels in red blood cells and carcinogen-DNA adducts in white blood cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

Gen-Air is a case-control study nested within the EPIC cohort designed to study the relationship between smoking related cancers and air pollution and environmental tobacco smoke, and has been described extensively elsewhere (Airoldi et al. 2005; Peluso et al. 2005a; Peluso et al. 2005b). Follow-up in EPIC was based on population cancer registries in seven of the participating countries: Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom. In France, Germany, and Greece, a combination of methods was used, including health insurance records, cancer and pathology registries, and active follow-up through study participants and their next-of-kin. Follow-up was virtually 100% complete. Individuals who were non-smokers at enrolment into EPIC or who were ex-smokers at enrolment and quit smoking ten years or more prior to enrolment were eligible for inclusion in Gen-Air. For analyses of questionnaire data up to three controls per case were matched on gender, age (± five years), smoking status (never or former smoker), country of recruitment, and follow-up time. The study was designed to have two of these controls per case be subjects from whom blood samples were available for biomarker analyses. Mean follow-up was 89 months (minimum, 51 months; maximum, 123 months). A total of 269 incident lung cancer cases were eligible for inclusion in GEN-AIR and 255 of these subjects could be matched to controls. Complete physical activity data were available from 230 cases and 648 matched controls.

At base line enrolment into the EPIC cohort, past week physical activity data were obtained via either in-person or self-administered interviews using a standardized questionnaire that has been extensively described elsewhere (Haftenberger et al. 2002; Steindorf et al. 2006). Data were gathered on the frequency and duration of non-occupational physical activities including housework, home repair (do-it-yourself), gardening, stair climbing, walking, cycling, and sports. Metabolic equivalent (MET) values were assigned to each reported activity to weight the activities by intensity level and MET-hours/week of activity were calculated (Ainsworth et al. 2000; Steindorf et al. 2006). Housework, home repair, gardening, and stair climbing were combined to estimate household activity. Recreational activity was calculated as the sum of walking, cycling and sports activities. EPIC respondents categorized themselves as having sedentary, standing, manual, heavy manual or no occupation.

A precursor to the EPIC physical activity questionnaire was tested for reliability and validity in Dutch study subjects (Pols et al. 1997). Compared to the final EPIC protocol, the validity study used different wording for the questions and a different approach for weighting the activities for energy expenditure, and so the validity study is not completely congruent with the physical activity analyses conducted with EPIC data (Pols et al. 1997). To provide further information on the relative validity of the physical activity measures in the population included in Gen-Air, analyses were conducted to determine whether increasing recreational, household and occupational activity were associated with BMI. These analyses do not provide a measure of absolute validity the way a comparison to a criterion measure of energy expenditure would, but are useful for providing a sense of the construct validity of physical activity questionnaires (Alfano et al. 2004; Bowles et al. 2004; DeVellis 1991; Jacobs et al. 1993; Washburn et al. 1991).

Laboratory analyses

Glutathione Levels

Blood samples were collected at baseline enrolment into the EPIC cohort. Glutathione levels were measured in the red blood cell samples that remained after prior analyses of 4-aminobiphenyl-haemoglobin adducts (51 lung cancer cases and 110 matched controls) (Airoldi et al. 2005). Study subjects were randomly selected for inclusion in the 4-aminobiphenyl adduct study. Availability of biological sample for GSH analyses was not associated with any of the physical activity variables, age at recruitment into EPIC, smoking status or years of smoking. Of the subjects with available samples physical activity data were only available from 43 cases and 92 controls. Total GSH levels, the sum of reduced and non-reduced GSH, were measured in red blood cell samples using a 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzenoic acid) colormetric assay as described previously (Richie et al. 1996; Rundle et al. 2005a). Haemoglobin levels were measured using Drabkin’s reagent and results are expressed as micro mole of GSH per gram of haemoglobin (Hb) to control for potential differences in red blood cell concentrations across samples and reported as GSH/Hb (Fairbanks and Klee 1987).

Carcinogen-DNA Adducts

Carcinogen-DNA adduct data were available from prior analyses of GEN-AIR study subjects (Peluso et al. 2005b). Blood samples for these analyses were available to GEN-AIR from all EPIC centers except Malmo, and DNA samples were available from 68% of the study subjects. Carcinogen-DNA adduct levels were measured in white blood cells collected from the study subjects at enrolment into EPIC using the 32P postlabelling assay as previously described (Peluso et al. 2005b). Briefly, DNA samples were treated with nuclease P1 and labeled with 25 to 50 μCi carrier-free [γ-32P] ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol/L). Separation of adduct species was conducted by two dimensional chromatography and adduct levels were quantified by Cerenkov counting or storage phosphorimaging techniques (Peluso et al. 2005b).

Statistical analyses

Conditional logistical regression analyses were used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95 percent confidence intervals for the association between lung cancer risk and physical activity. Quartile cut points were calculated for increasing levels of recreational and household activity based on the distribution of activity levels in the controls, and dummy variables for the quartiles were entered into the statistical model. For occupational activity the sitting category was used as the referent and dummy variables were created to indicate categories of occupational activity. Standing, manual and heavy manual occupations were combined because of the low numbers of cases in each of the respective categories. Analyses simultaneously considered the effects of increasing activity in the separate domains of recreational, household and occupational activity.

The initial conditional logistic regression analyses controlled for gender, age category, country, and smoking status through the individual matching and further analyses also controlled for smoking duration. For the purposes of classifying subjects on smoking status, cigarette, cigar and pipe smoking were treated as equivalent and like wise data on cigarettes, pipes and cigars was used to calculate duration of smoking. Data on number of cigarettes smoked per day was not commonly available in the data set for these ex-smokers and pack-years of smoking could not be calculated. Years of smoking was entered into the models as a continuous variable and never-smokers were assigned a value of zero. Data on passive smoke exposure at work or at home was not collected at all of the EPIC sites, only 59 of the cases with physical activity data also had data on passive smoke exposure. Thus, it was not possible to adequately control for passive smoke exposure. Education level, body mass index (BMI), total calorie intake, and servings of fruits and vegetables were also evaluated as potential confounders.

Conditional logistic regression analyses were used to determine whether increasing GSH levels in red blood cells were protective against lung cancer. Because of the small number of cases and controls included in these pilot analyses, GSH levels were analyzed as a continuous variable and then again separately analyzed as a dichotomous variable using the median level in the controls as the cut point to designate high and low levels.

Analyses of associations between physical activity categories and BMI and GSH levels among controls were conduced using generalized estimating equations (GEE) (Rundle et al. 2005b). Adjusted means and 95 percent confidence intervals were calculated for BMI and GSH level by physical activity quartile categories. The association between categories of physical activity and aromatic-DNA adduct levels in white blood cells was also assessed. As is common the adduct data were not normally distributed and 15% of subjects had adduct levels below the detection limit of the postlabeling assay. As such mathematical transformations of the data did no improve the distribution of the continuous data for analytical purposes. Thus, the data were dichotomized into high and low adduct level groups using the median value in the controls as the cut point. The association between physical activity categories and the presence of high aromatic-DNA adduct levels in white blood cells was assessed using GEE and results are reported as the odds ratio and corresponding 95% confidence interval. P-values were calculated comparing the mean BMI, GSH level and odds of high adduct levels in each ascending physical activity quartile category compared to the lowest.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics on the demographics and physical activity levels of the 230 lung cancer cases and 648 individually matched controls. Table 2 shows the results for conditional logistic regression analyses of physical activity categories and lung cancer with results for each domain of activity mutually adjusted for the effects of the other domains. In analyses that considered the matching variables as potential confounders and in analyses that further controlled for years of smoking, increasing levels of recreational physical activity were significantly protective against lung cancer. Increasing levels of household activity were non-significantly positively associated with lung cancer risk. Compared to sedentary occupations, jobs that required physical activity were not associated with lung cancer, nor was being unemployed. Further control for BMI, education, energy intake and consumption of fruits and vegetables did not substantially alter the results observed in the initial conditional logistic regression model. In analyses of the subset of 59 cases and 216 controls for whom passive smoke exposure data were available recreational physical activity was not significantly associated with lung cancer risk and further control for passive smoke exposure did not appreciably alter the OR estimates. However, due to the small sample size the models appeared quite unstable and it was not possible to fully evaluate potential confounding by passive smoke exposure.

TABLE 1.

Demographic, smoking and physical activity characteristics of cases and controls

| Categorical Variables | Cases n=230 n (%) | Controls n=648 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 72 (31%) | 207 (32%) |

| Female | 158 (69%) | 441 (68%) |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Never | 124 (54%) | 348 (54%) |

| Ex-smoker | 106 (46%) | 300 (46%) |

| Occupational Physical Activity | ||

| Sitting | 36 (16%) | 112 (17%) |

| Standing | 44 (19%) | 129 (20%) |

| Manual/Heavy | 10 (4%) | 32 (5%) |

| Not Employed | 140 (61%) | 375 (58%) |

|

| ||

| Continuous Variables | Mean, SD, n | Mean, SD, n |

|

| ||

| Age at recruitment | 60.30, 8.96, 230 | 60.33, 8.98, 648 |

| Body Mass Index | 25.64, 4.03, 230 | 25.45, 4.11, 648 |

| Years of Smoking Among Ex-smokers | 24.26, 11.68, 102 | 22.22, 11.43, 285 |

| Years Since Quitting Smoking Among Ex- smokers | 20.66, 7.92, 106 | 22.38, 9.97, 300 |

| Recreational Physical Activity MET*Hours/Week | 26.88, 23.68, 230 | 30.12, 25.17, 648 |

| Household Physical Activity MET*Hours/Week | 49.16, 35.84, 230 | 47.00, 36.82, 648 |

TABLE 2.

Odds Ratios (OR) for physical activity* and lung cancer

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1† | Model 2‡ | |||

|

| ||||

| (n=878) | (n=847) | |||

| OR | (95 % CI) | OR | 95% CI | |

| Recreational (MET * hours/ Week) | ||||

| 0–12.00 | 1 | 1 | ||

| >12.00–24.00 | 0.75 | (0.49, 1.15) | 0.77 | (0.50, 1.19) |

| >24.00–39.00 | 0.59 | (0.37, 0.92) | 0.58 | (0.37, 0.93) |

| >39.00 | 0.60 | (0.37, 0.95) | 0.56 | (0.35, 0.90) |

| Ptrend | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||

|

| ||||

| Household (MET* hours/week) | ||||

| 0–19.00 | 1 | 1 | ||

| >19.00–36.50 | 1.05 | (0.66, 1.67) | 1.07 | (0.66, 1.71) |

| >36.50–63.30 | 1.10 | (0.69, 1.76) | 1.08 | (0.67, 1.75) |

| >63.30 | 1.53 | (0.91, 2.56) | 1.55 | (0.91, 2.63) |

| Ptrend | 0.13 | 0.14 | ||

|

| ||||

| Occupational | ||||

| Sitting | 1 | 1 | ||

| Standing/Manual/Heavy | 0.99 | (0.58, 1.70) | 1.03 | (0.60, 1.79) |

| Not Employed | 1.24 | (0.72, 2.16) | 1.25 | (0.72, 2.18) |

| Year of Smoking | NA | 1.04 | (1.01, 1.08) | |

Results for recreational, household and occupational activity mutually adjusted for each other domain of activity.

Model 1 controls for matching variables

Model 2 controls for matching variables and total years of smoking.

Table 3 presents the results of analyses separately for never-smokers and long term ex-smokers. Among never-smokers those in the third and fourth quartile of recreational activity were at non-significantly lower risk, while household activity was significantly associated with increased risk. Among ex-smokers each category of recreational physical activity above the reference category had a rate ratio of around 0.50, suggesting a protective effect but no dose-response related to increasing activity above the reference category. Occupational activity remained un-associated with lung cancer regardless of smoking status.

TABLE 3.

Odds ratios (OR) for physical activity* and lung cancer by smoking status

|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never-Smoker | Ex-smoker | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Model 1† | Model 1† | Model 2‡ | ||||

|

| ||||||

| (n=472) | (n=406) | (n=387) | ||||

| OR | (95 % CI) | OR | (95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | |

| Recreational (MET * hours/ Week) | ||||||

| 0–12.00 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| >12.00–24.00 | 1.16 | (0.66, 2.05) | 0.42 | (0.21, 0.84) | 0.43 | (0.21, 0.89) |

| >24.00–39.00 | 0.64 | (0.35, 1.17) | 0.58 | (0.29, 1.18) | 0.57 | (0.27, 1.18) |

| >39.00 | 0.73 | (0.39, 1.38) | 0.46 | (0.23, 0.92) | 0.41 | (0.20, 0.84) |

| Ptrend | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.04 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Household (MET * hours/ Week) | ||||||

| 0–19.00 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| >19.00–36.50 | 1.29 | (0.68, 2.45) | 0.96 | (0.47, 1.96) | 1.01 | (0.48, 2.13) |

| >36.50–63.30 | 1.41 | (0.71, 2.79) | 0.93 | (0.46, 1.85) | 0.90 | (0.43, 1.86) |

| >63.30 | 2.50 | (1.18, 5.37) | 1.03 | (0.49, 2.14) | 1.03 | (0.46, 2.19) |

| Ptrend | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.94 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Occupational | ||||||

| Sitting | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Standing/Manual/Heavy | 0.96 | (0.47, 1.96) | 0.83 | (0.35, 1.96) | 0.90 | (0.37, 2.19) |

| Not Employed | 1.04 | (0.50, 2.17) | 1.43 | (0.61, 3.34) | 1.47 | (0.61, 3.53) |

|

| ||||||

| Years of smoking | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.04 | (1.003, 1.07) |

Results for recreational, household and occupational activity mutually adjusted for each other domain of activity.

Model 1 controls for matching variables

Model 2 controls for matching variables and total years of smoking.

Table 4 presents the results of analyses of BMI, GSH/Hb levels in red blood cells and high adduct aromatic-DNA adduct levels in white blood cells and categories of physical activity among controls. Increasing recreational activity was significantly associated with lower BMI (ptrend=0.02), while household and occupational activity were not. Increasing recreational physical activity was positively associated with GSH/Hb levels, while household activity was not. Occupational activity was not associated with GSH/Hb but compared to subjects engaged in sitting occupations, unemployed subjects have significantly lower GSH/Hb levels. Increasing levels of GSH/Hb were not associated with lung cancer case-control status, OR=0.95 (95 percent confidence interval: 0.84, 1.07) per unit GSH/Hb and OR=0.95 (95 percent confidence interval: 0.43, 2.09) comparing high to low levels of GSH/Hb. There were no apparent associations between the presence of aromatic-DNA adducts and physical activity categories, although increasing BMI was inversely associated with the presence of high adduct levels (Beta = −0.07, P=0.05).

TABLE 4.

Associations between physical activity* and BMI, Glutathione and Carcinogen-DNA adducts among controls

| BMI† Adjusted Mean (95% CI), P N=648 | GSH/Hb‡ Adjusted Mean, (95% CI), P N=92 | Carcinogen-DNA Adduct Levels above the Median††. OR, (95% CI) P N=208 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recreational (MET * hours/Week) | |||

| 0 – 12.00 | 25.93 (25.19, 26.67) | 8.16 (7.33, 8.99) | Ref |

| >12.00 – 24.00 | 25.64 (25.03, 26.25) P=0.52 |

8.92 (7.40, 10.44) P=0.39 |

1.31 (0.46, 3.67) P=0.61 |

| >24.00 – 39.00 | 25.27 (24.68, 25.86) P=0.15 |

8.94 (7.95, 9.993) P=0.23 |

1.38 (0.49, 3.94) P=0.54 |

| >39.00 | 24.90 (24.32, 25.48) P=0.03 |

10.03 (8.41, 11.65) P=0.04 |

1.05 (0.38, 2.86) P=0.93 |

|

| |||

| Household (MET * hours/ Week) | |||

| 0 – 19.00 | 25.17 (24.60, 25.74) | 9.73 (7.71, 11.75) | Ref |

| >19.00 – 36.50 | 24.95 (24.28, 25.63) P=0.61 |

8.35 (7.45, 9.27) P=0.36 |

1.48 (0.54, 4.06) P=0.44 |

| > 36.50 – 63.30 | 25.46 (24.88, 26.04) P=0.48 |

8.84 (7.78, 9.91) P=0.10 |

1.84 (0.69, 4.90) P=0.22 |

| > 63.30 | 26.16 (25.38, 26.95) P=0.05 |

9.58 (8.35, 10.81) P=0.89 |

0.94 (0.37, 2.41) P=0.90 |

|

| |||

| Occupational | |||

| Sitting | 25.25 (24.49, 26.01) | 10.49 (9.25, 11.72) | Ref |

| Standing/Manual /Heavy | 25.02 (24.40, 25.65) p=0.63 |

9.35 (7.91, 10.78) P=0.19 |

0.90 (0.33, 2.47) P=0.84 |

| Not Employed | 25.68 (25.20, 26.16) p=0.37 |

8.20 (7.21, 9.18) P<0.01 |

1.30 (0.57, 2.92) P=0.53 |

Results for recreational, household and occupational activity mutually adjusted for each other domain of activity.

Adjusted for gender and smoking status.

Adjusted for gender, age at recruitment, energy intake, and fruit and vegetable consumption

Adjusted for laboratory batch, age at recruitment, BMI and gender.

Since household activity was not associated with BMI and appeared to be positively associated with lung cancer risk, separate post hoc analyses were conducted of the component physical activity measures that comprise household activity (housework, home repair (do-it-yourself), gardening, and stair climbing). Except for stair climbing, increasing activity in each of these areas was modestly, positively, but not significantly, associated with lung cancer risk. Among ex-smokers the positive association between gardening and lung cancer approached statistical significance, ptrend =0.07 (details not shown).

DISCUSSION

Preventing the initiation of smoking and promoting smoking cessation remain the primary means of preventing lung cancer. However there are few prevention programs available to never- or ex-smokers, and so the possibility that physical activity prevents lung cancer in these groups is of tremendous public health interest (Lee et al. 1999; Mao et al. 2003). Although not initially designed to investigate the role of physical activity, the GEN-AIR study, with its focus on never- and long term ex-smokers and the availability of biological samples, presents an interesting context in which to study physical activity (Peluso et al. 2005a). This the first study to incorporate intermediate biomarker analyses into a prospective analysis of physical activity and cancer and the first analysis of blood GSH levels and lung cancer risk. A previous report from the entire cohort found no overall protective effect, and no protective effects by smoking status (Steindorf et al. 2006). The major difference between these two analyses is the restriction of ex-smokers to those who had quit smoking 10 years or more prior to entry into EPIC and may explain the differences in results. As noted in the Introduction, smoking cessation is associated in variable and complex ways with changes in other lifestyle risk factors including physical activity. There is evidence that among some ex-smokers quitting is associated with increases in physical activity, while among others cessation is prompted by declining health, which also impacts the ability to engage in activity. The restriction of ex-smoking cases to those who quit ten or more years prior to entry into EPIC reduces the possibility that activity patterns measured at entry into the cohort are associated with the decision to quit and with health status at the time of quitting.

The analyses presented here provide further evidence that recreational activity is protective against lung cancer risk in ex- and non-smokers. To place the results in context 30 MET*hours of recreational activity is equivalent to 5 hours of cycling. These results are consistent with those from the Harvard Alumni Study, the Canadian National Enhanced Cancer Surveillance System study and the Iowa Women’s Health Study (Lee et al. 1999; Mao et al. 2003; Sinner et al. 2006). Physical activity can induce endogenous antioxidant defenses which can reduce the damage caused by episodes of oxidative stress (Miyazaki et al. 2001), theoretically this response could protect against both initiation and promotion caused by oxidative stress (Cerutti 1985; Frenkel 1992). However in GEN-AIR household activity was positively associated with risk and in some analyses this association was statistically significant, whereas occupational activity was not associated with risk. Again to place these results in context, 30 MET*hours of household activity is equivalent to 10 hours of housework. Steindorf and colleagues have analyzed the association between physical activity and lung cancer risk in the EPIC cohort, which partially overlaps with GEN-AIR (Steindorf et al. 2006). They did not observe an inverse association between lung cancer risk and recreational or household physical activity. Some reductions were found with sports in males, cycling in females and non-occupational vigorous physical activity. For occupational physical activity, lung cancer risks were increased for unemployed men and men with standing occupations.

The divergent results for recreational and household activity may be construed as calling into question whether energy expenditure through physical activity is biologically protective against lung cancer. A priori one would not expect to observe associations between increased activity and risk that differ by domain of activity. However, it is possible that the questions on recreational and household activity are not equivalently valid measures of their respective domains of physical activity. Consistent with this possibility is the observation that BMI significantly decreases with increasing levels of recreational activity among controls but is not consistently associated with household activity. Another possibility is that given the relatively short duration of follow up, subjects with low engagement in recreational physical activity were less active in this domain because of sub-clinical disease symptoms. The design reduces biases that might occur if decisions to quit smoking were associated with activity patterns measured at baseline. However, it doesn’t address the possibility that at baseline cases were expressing symptoms related to lung cancer or other co-morbid conditions that influenced their activity levels. It is possible for instance that those with poor health didn’t engage in recreation but did engage in more hours of lower intensity household activity, explaining the divergent results for recreational and household activity.

It is unclear why household activity appears to be detrimental and particularly so among never-smokers, although the results among the never-smokers may just be an artifact of the modest sample size. The measurement of household activity does present more challenges than the measurement of recreational activity and the lack of association between BMI and household activity suggests that this measure may be less valid. However, measurement error would explain null results but not the increased risk observed here. Separate analyses of housework, home repair (do-it-yourself), and gardening, three of the four measures that comprise total household activity, showed similar associations with lung cancer risk. It is possible that the questions regarding household activity tap into a socio-economic related effect not controlled for by education or that there are exposures associated with gardening, do it yourself projects and housework that are detrimental. In this case the questions may be measuring unknown factors related to risk that are associated with doing household work.

Past studies of occupational activity have generally shown null findings (Colbert et al. 2002; Dosemeci et al. 1993; Paffenbarger et al. 1987; Severson et al. 1989; Steenland et al. 1995; Thune and Lund 1997), although a few have found elevated risks of lung cancer with increased occupational physical activity (Bak et al. 2005; Brownson et al. 1991; Steindorf et al. 2006). In the Danish component of EPIC lung cancer was significantly increased for men and women reporting standing occupations, but not for light activity or heavy activity occupations (Bak et al. 2005). In earlier analyses of the entire EPIC cohort, risk of lung cancer was elevated for unemployed men and for men who reported standing occupations (Steindorf et al. 2006). One difficulty in analyzing the data on occupational activity is that the questionnaire collected data on occupational activity at enrollment into the cohort, and more than half of the subjects were not employed. The analyses of occupational activity is also complicated by the possibility that increased activity on the job may be associated with industrial occupations that increase ones risk for lung cancer. Thus any putative benefit of occupational physical activity may be obscured by occupational exposures. Again this may be another instance where the questionnaire data on physical activity not only taps into the construct of physical activity but other processes as well. However, further control for employment in at risk occupations did not alter these results.

The biomarker data may further illuminate the results of the questionnaire data on physical activity. GSH is an important endogenous antioxidant that detoxifies reactive oxygen species thought to act both as tumor initiators and promoters (Cerutti 1985; Frenkel 1992). Furthermore, as a co-factor of glutathione transferases, GSH plays an important role in detoxifying chemical carcinogens (Bartsch et al. 1991; Jernstrom et al. 1982). Relevant to the work presented here, GSH levels have been shown to be positively associated with physical activity (Karolkiewicz et al. 2003; Robertson et al. 1991; Rundle et al. 2005a) and to increase with physical training (Evelo et al. 1992). The associations between GSH levels and recreational activity among controls parallel those seen between recreational physical activity and lung cancer risk, while household activity is not associated with GSH. This suggests that the questions on recreational activity are measuring physical activity related behavior that is having a physiological effect while the questions on household activity may not be. Again this is consistent with the observation that recreational activity is associated with BMI while household activity is not. Among those employed, occupational activity is not associated with GSH level, however those unemployed have significantly lower levels of GSH that those in sedentary jobs. These analyses controlled for age and past research has shown that for any given age being unemployed is associated with lower health status (Arrighi and Hertz-Picciotto 1994; Richardson et al. 2004), and GSH levels have been seen to be lower in those with poorer general health (Julius et al. 1994; Nuttall et al. 1998). Thus lower GSH levels seen among the not employed may reflect the general lower health status common to this group. As described above, there are good biological reasons to expect GSH to be protective against lung cancer, however GSH levels were not associated with lung cancer risk, although the sample size was small in these pilot analyses.

A prior report from GEN-AIR has shown that the presence of carcinogen-DNA adducts was associated with lung cancer risk (Peluso et al. 2005b). Past studies have shown increases in UDP-glucuronosyl transferase and glutathione S-transferases activities associated with running (Duncan et al. 1997; Evelo et al. 1992). However contrary to expectations, a past analysis of physical activity found that increased hours of moderate intensity physical activity was positively associated with the presence of BP-DNA adducts (Rundle et al. 2007). Also of relevance to energy balance are the findings that increased BMI is associated with lower carcinogen-DNA adducts and among ex-smokers with a longer half-life of carcinogen-DNA adducts in white blood cells (Godschalk et al. 2002; Rundle et al. 2007). In the analyses presented here physical activity was not associated with the presence of high levels of carcinogen-DNA adducts in white blood cells, suggesting that any effect of activity on lung cancer risk is not mediated by altering the amount of genetic damage caused by chemical carcinogens. However, increasing BMI was inversely associated with the presence of high levels of carcinogen DNA adducts among controls.

These results provide further evidence that recreational activity is associated with lower risk of lung cancer among non- and ex-smokers. This has particularly important implications for ex-smokers, who remain at high risk for lung cancer and after quitting have few options for further lowering their risk. The restriction of the study to long term ex-smokers reduces methodological issues associated with studying physical activity in ex-smokers, however further follow-up of the cohort is required to rule out other ways in which reverse causality can arise. In addition, because of the limited data collected in EPIC it was not possible to control for passive smoke exposure, it is possible that those who are more recreationally active have lower exposure to passive smoke. The biomarker and BMI analyses suggest that the data do reflect patterns of recreational physical activity that are having physiological consequences and thus lend weight to the findings on lung cancer risk. This research adds to the existing literature suggesting that physical activity programs may be useful as an adjunct of smoking prevention and cessation in preventing lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided to Dr. Rundle by a Career Development Award from the National Cancer Center (KO7-CA92348-01A1).

References

- Ainsworth B, Haskell W, Whitt M, Irwin M, Swartz A, Strath S, O’Brien W, Bassett D, Schmitz K, Emplaincourt P, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airoldi L, Vineis P, Colombi A, Olgiati L, Dell’Osta C, Fanelli R, Manzi L, Veglia F, Autrup H, Dunning A, et al. 4-Aminobiphenyl-Hemoglobin Adducts and Risk of Smoking-Related Disease in Never Smokers and Former Smokers in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Prospective Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(9):2118–2124. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano CM, Klesges RC, Murray DM, Bowen DJ, McTiernan A, Vander Weg MW, Robinson LA, Cartmel B, Thornquist MD, Barnett M, et al. Physical activity in relation to all-site and lung cancer incidence and mortality in current and former smokers. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2004;13(12):2233–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi HM, Hertz-Picciotto I. The evolving concept of the healthy worker survivor effect. Epidemiology. 1994;5(2):189–96. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak H, Autrup H, Thomsen B, Tjønneland A, Overvad K, Vogel U, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Loft S. Bulky DNA adducts as risk indicator of lung cancer in a Danish case-cohort study. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;118(7):1618–1622. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak H, Christensen J, Thomsen BL, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Loft S, Raaschou-Nielsen O. Physical activity and risk for lung cancer in a Danish cohort. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;116(3):439–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch H, Petruzzelli S, De Flora S, Hietanen E, Camus A, Castegnaro M, Geneste O, Camoirano A, Saracci R, Giuntini C. Carcinogen metabolism and DNA adducts in human lung tissues as affected by tobacco smoking or metabolic phenotype: a case-control study on lung cancer patients. Mutat Res. 1991;250(1–2):103–14. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(91)90167-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehme D, Hotchkiss J, Henderson R. Glutathione and GSH-dependent enzymes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cells in response to ozone. Exp Mol Pathol. 1992;56(1):37–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(92)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles HR, FitzGerald SJ, Morrow JR, Jr, Jackson AW, Blair SN. Construct validity of self-reported historical physical activity. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;160(3):279–86. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle RG, O’Connor P, Pronk N, Tan A. Health behaviors of smokers, ex-smokers, and never smokers in an HMO. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31(2 Pt 1):177–82. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson R, Chang J, Davis J, Smith C. Physical activity on the job and cancer in Missouri. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(5):639–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantin A, North S, Hubbard R, Crystal R. Normal alveolar epithelial lining fluid contains high levels of glutathione. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63(1):152–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti P. Prooxidant states and tumor promotion. Science. 1985;227(4685):375–81. doi: 10.1126/science.2981433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert L, Hartman T, Tangrea J, Pietinen P, Virtamo J, Taylor P, Albanes D. Physical activity and lung cancer risk in male smokers. Int J Cancer. 2002;98(5):770–3. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis R. Scale development: theory and applications. Newbury Park, Ca: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty SC, Steptoe A, Rink E, Kendrick T, Hilton S. Readiness to change health behaviours among patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Risk. 1998;5(3):147–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosemeci M, Hayes RB, Vetter R, Hoover RN, Tucker M, Engin K, Unsal M, Blair A. Occupational physical activity, socioeconomic status, and risks of 15 cancer sites in Turkey. Cancer Causes & Control. 1993;4(4):313–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00051333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan K, Harris S, Ardies CM. Running exercise may reduce risk for lung and liver cancer by inducing activity of antioxidant and phase II enzymes. Cancer Letters. 1997;116(2):151–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons KM, Marcus BH, Linnan L, Rossi JS, Abrams DB. Mechanisms in multiple risk factor interventions: smoking, physical activity, and dietary fat intake among manufacturing workers. Working Well Research Group. Preventive Medicine. 1994;23(4):481–9. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evelo C, Palmen N, Artur Y, Janssen G. Changes in blood glutathione concentrations, and in erythrocyte glutathione reductase and glutathione S-transferase activity after running training and after participation in contests. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1992;64(4):354–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00636224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks V, Klee G. Biochemical aspects of hematology. In: Tietz N, editor. Fundamentals of clinical chemistry. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Autier P, Boniol M, Heanue M, Colombet M, Boyle P. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(3):581–92. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman PA, Khan ZM, Thompson EE, Curry SJ. Health care costs among smokers, former smokers, and never smokers in an HMO. Health Services Research. 2003;38(2):733–49. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel K. Carcinogen-mediated oxidant formation and oxidative DNA damage. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;53(1):127–66. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett NA, Alesci NL, Schultz MM, Foldes SS, Magnan SJ, Manley MW. The relationship of stage of change for smoking cessation to stage of change for fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity in a health plan population. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2004;19(2):118–27. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godschalk RWL, Feldker DEM, Borm PJA, Wouters EFM, Van Schooten F-J. Body Mass Index Modulates Aromatic DNA Adduct Levels and Their Persistence in Smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(8):790–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haftenberger M, Schuit AJ, Tormo MJ, Boeing H, Wareham N, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Kumle M, Hjartaker A, Chirlaque MD, Ardanaz E, et al. Physical activity of subjects aged 50–64 years involved in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(6B):1163–76. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern MT, Warner KE. Differences in former smokers’ beliefs and health status following smoking cessation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10(1):31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman-Goetz L, Apter D, Demark-Wahnefried W, Goran M, McTiernan A, Reichman M. Possible mechanism mediating an association between physical activity and breast cancer. Cancer. 1998;83(3):621–628. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980801)83:3+<621::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs DR, Jr, Ainsworth BE, Hartman TJ, Leon AS. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1993;25(1):81–91. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernstrom B, Babson J, Moldeus P, Holmgren A, Reed D. Glutathione conjugation and DNA-binding of (+/−)-trans-7,8-dihydroxy-7,8-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene and (+/−)-7 beta,8 alpha-dihydroxy-9 alpha,10 alpha-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene in isolated rat hepatocytes. Carcinogenesis. 1982;3(8):861–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/3.8.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Bliss RL, Zhao F, Lando H. Predictors of smoking reduction without formal intervention. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7(2):277–82. doi: 10.1080/14622200500056176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julius M, Lang CA, Gleiberman L, Harburg E, DiFranceisco W, Schork A. Glutathione and morbidity in a community-based sample of elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(9):1021–6. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karolkiewicz J, Szczesniak L, Deskur-Smielecka E, Nowak A, Stemplewski R, Szeklicki R. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense system in healthy, elderly men: relationship to physical activity. Aging Male. 2003;6(2):100–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada T. Comparison of daily life habits and health examination data between smokers and ex-smokers suggests that ex-smokers acquire several healthy-lifestyle practices. Archives of Medical Research. 2004;35(4):329–33. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly F. Gluthathione: in defence of the lung. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37(9–10):963–6. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubik A, Zatloukal P, Tomasek L, Pauk N, Havel L, Dolezal J, Plesko I. Interactions between smoking and other exposures associated with lung cancer risk in women: diet and physical activity. Neoplasma. 2007;54(1):83–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Paffenbarger R. Physical activity and its relation to cancer risk: a prospective study of college alumni. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(7):831–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Sesso H, Paffenbarger R. Physical activity and risk of lung cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(4):620–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitzmann MF, Koebnick C, Abnet CC, Freedman ND, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Ballard-Barbash R, Schatzkin A. Prospective study of physical activity and lung cancer by histologic type in current, former, and never smokers. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(5):542–53. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Pan S, Wen SW, Johnson KC Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research G. Physical activity and the risk of lung cancer in Canada. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;158(6):564–75. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTiernan A, Ulrich C, Slate S, Potter S. Physical activity and cancer etiology: associations and mechanisms. Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9(5):487–509. doi: 10.1023/a:1008853601471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelet F, Gueguen R, Leroy P, Wellman M, Nicolas A, Siest G. Blood and plasma glutathione measured in healthy subjects by HPLC: relation to sex, aging, biological variables, and life habits. Clin Chem. 1995;41(10):1509–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki H, Oh-ishi S, Ookawara T, Kizaki T, Toshinai K, Ha S, Haga S, Ji LL, Ohno H. Strenuous endurance training in humans reduces oxidative stress following exhausting exercise. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2001;84(1–2):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s004210000342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall SL, Martin U, Sinclair AJ, Kendall MJ. Glutathione: in sickness and in health. Lancet. 1998;351(9103):645–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL. Physical activity and incidence of cancer in diverse populations: a preliminary report. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1987;45(1 Suppl):312–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.1.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso M, Hainaut P, Airoldi L, Autrup H, Dunning A, Garte S, Gormally E, Malaveille C, Matullo G, Munnia A, et al. Methodology of laboratory measurements in prospective studies on gene-environment interactions: the experience of GenAir. Mutat Res. 2005a;574(1–2):92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso M, Munnia A, Hoek G, Krzyzanowski M, Veglia F, Airoldi L, Autrup H, Dunning A, Garte S, Hainaut P, et al. DNA Adducts and Lung Cancer Risk: A Prospective Study. Cancer Res. 2005b;65(17):8042–8048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pols M, Peeters P, Ocke M, Slimani N, Bueno-De-Mesquita H, Collette H. Estimation of reproducibility and relative validity of the questions included in the EPIC physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(1 suppl 1):s181–s189. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.s181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D, Wing S, Steenland K, McKelvey W. Time-related aspects of the healthy worker survivor effect. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(9):633–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie J, Skowronski L, Abraham P, Leutzinger Y. Blood glutathione concentrations in a large-scale human study. Clin Chem. 1996;42(1):64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J, Maughan R, Duthie G, Morrice P. Increased blood antioxidant systems of runners in response to training load. Clin Sci (Colch) 1991;80(6):611–8. doi: 10.1042/cs0800611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins J. The control of confounding by intermediate variables. Statistics in Medicine. 1989;8(6):679–701. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):550–60. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundle A. The molecular epidemiology of physical activity and cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers and Prev. 2005;14:227–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundle A, Madsen A, Orjuela M, Mooney L, Tang D, Kim M, Perera F. The association between benzo[a]pyrene-DNA adducts and body mass index, calorie intake and physical activity. Biomarkers. 2007;12(2):123–32. doi: 10.1080/13547500601010418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundle A, Orjuela M, Mooney L, Tang D, Kim M, Calcagnotto A, Richie J, Perera F. Moderate physical activity is associated with increased blood levels of glutathione among smokers. Biomarkers. 2005a;10(5):3390–400. doi: 10.1080/13547500500272663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundle AG, Vineis P, Ahsan H. Design Options for Molecular Epidemiology Research within Cohort Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005b;14(8):1899–1907. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson RK, Nomura AM, Grove JS, Stemmermann GN. A prospective analysis of physical activity and cancer. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1989;130(3):522–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinner P, Folsom AR, Harnack L, Eberly LE, Schmitz KH. The association of physical activity with lung cancer incidence in a cohort of older women: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(12):2359–63. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Klein BE, Klein R, Cruickshanks KJ, Lee KE, Hampton JM. Physical activity, white blood cell count, and lung cancer risk in a prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(10):2714–22. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K, Nowlin S, Palu S. Cancer incidence in the National Health and Nutrition Survey I. Follow-up data: diabetes, cholesterol, pulse and physical activity. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 1995;4(8):807–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steindorf K, Friedenreich C, Linseisen J, Rohrmann S, Rundle A, Veglia F, Vineis P, Johnsen NF, Tjønneland A, Overvad K, et al. Physical activity and lung cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(10):2389–97. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D, Phillips D, Stampfer M, Mooney L, Hsu Y, Cho S, Tsai W, Ma J, Cole K, She M, et al. Association between carcinogen-DNA adducts in white blood cells and lung cancer risk in the physicians health study. Cancer Res. 2001;61(18):6708–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D, Rundle A, Warburton D, Santella R, Tsai W, Chiamprasert S, Hsu Y, FPP Associations between both genetic and environmental biomarkers and lung cancer: evidence of a greater risk of lung cancer in women smokers. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(11):1949–53. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.11.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Muir J, Lancaster T, Jones L, Fowler G. Health profiles of current and former smokers and lifelong abstainers. OXCHECK Study Group. OXford and Collaborators HEalth ChecK. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London. 1997;31(3):304–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thune I. Assessments of physical activity and cancer risk. Eur J Can Prev. 2000;9(6):387–93. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thune I, Lund E. The influence of physical activity on lung-cancer risk: A prospective study of 81,516 men and women. nt J Cancer. 1997;70(1):57–62. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970106)70:1<57::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twardella D, Loew M, Rothenbacher D, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. The diagnosis of a smoking-related disease is a prominent trigger for smoking cessation in a retrospective cohort study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2006;59(1):82–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veglia F, Loft S, Matullo G, Peluso M, Munnia A, Perera F, Phillips DH, Tang D, Autrup H, Raaschou-Nielsen O, et al. DNA adducts and cancer risk in prospective studies: a pooled analysis and a meta-analysis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(5):932–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veglia F, Matullo G, Vineis P. Bulky DNA adducts and risk of cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(2):157–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Curry SJ, Grothaus L, Saunders KW, McBride CM. The impact of smoking and quitting on health care use. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1995;155(16):1789–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn RA, Smith KW, Goldfield SR, McKinlay JB. Reliability and physiologic correlates of the Harvard Alumni Activity Survey in a general population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1991;44(12):1319–26. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90093-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun YH, Lim MK, Won YJ, Park SM, Chang YJ, Oh SW, Shin SA. Dietary preference, physical activity, and cancer risk in men: national health insurance corporation study. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:366. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]