Abstract

Protein kinase CK2 is a highly conserved and ubiquitous serine–threonine kinase. It is a tetrameric enzyme that is made up of two regulatory CK2β subunits and two catalytic subunits, either CK2α/CK2α, CK2α/ CK2α′, or CK2α′/CK2α′. Although the two catalytic subunits diverge in their C termini, their enzymatic activities are similar. To identify the specific function of the two catalytic subunits in development, we have deleted them individually from the mouse genome by homologous recombination. We have previously reported that CK2α′is essential for male germ cell development, and we now demonstrate that CK2α has an essential role in embryogenesis, as mice lacking CK2α die in mid-embryogenesis, with cardiac and neural tube defects.

Keywords: Protein kinase CK2, Casein kinase II, Homologous recombination, Wnt signaling, Embryonic development

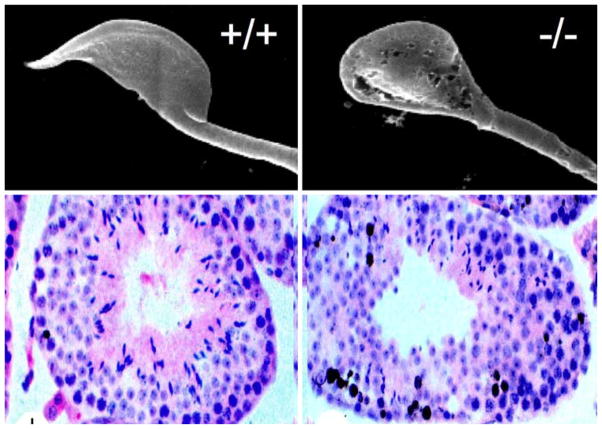

CK2 is a ubiquitous and highly conserved serine–threonine kinase. It is overexpressed in many human cancers, and we have shown that tissue-specific overexpression in transgenic mice leads to malignancy [1, 2]. One of the mechanisms of cellular transformation may be activation of the Wnt pathway, as CK2 is sufficient and necessary for stabilizing the key transcriptional co-factor in Wnt signaling, β-catenin [3–5]. CK2 can be found in transcriptional complexes on Wnt-target genes [6] and is activated by Wnt signaling [7]. In Xenopus laevis, CK2 is required for proper development of the dorsal axis of the embryo [5, 8]. In mice, CK2β is required for early embryonic development, and perhaps cell-autonomous growth [9]. We have previously shown that CK2α′ is highly expressed in mouse testis and brain and is required for normal male germ cell development [10]; no central nervous system phenotype has been found. In the testis, CK2α′ appears to protect developing spermatocytes from apoptosis, and deficiency leads to oligospermia and abnormal development of the sperm head (Fig. 1). We now have found that the more abundant and widely expressed CK2α subunit is required for mouse embryonic development. This report summarizes additional features of these knockout mice, first described in [11].

Fig. 1.

Male CK2α′−/− knockout mice have abnormal sperm development. By scanning electron microscopy (upper panel), defective development of the normally sickle-shaped mouse sperm head is seen. This phenotype is reminiscent of the human globozoospermia (round-headed sperm) syndrome in humans. In cross sections of the seminiferous tubules, the knockouts were found to have an increased number of apoptotic precursor cells, identified by TUNEL staining (lower panel)

Methods

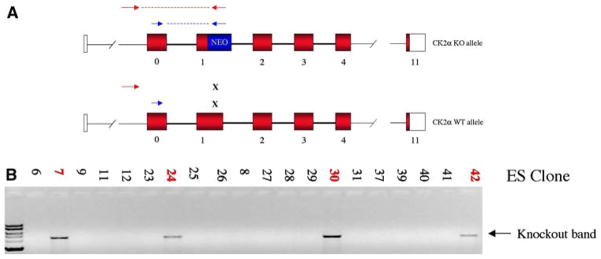

Gene targeting

Long-range PCR was used to amplify CK2α genomic DNA from a 129SvEv BAC clone. Arms were cloned into the pPNT targeting vector, which allows for positive and negative selection [12]. This construct (Fig. 2a) was electroporated into TC1 ES cells [13] grown on mitomycin-treated mouse embryonic fibroblast feeders in medium supplemented with 5 × 105 U ESGRO-LIF (Chemicon). Integration of the plasmid was selected for in 260 μg/ml G418 (Gibco), and cells with homologous recombination were enriched using 0.1 μM FIAU. DNA was prepared from surviving ES cell clones, and homologous recombinants were identified by PCR and Southern blot (Fig. 2b). Clones with containing a targeted CK2α allele were microinjected into C57Bl/6 blastocysts. All animal experimentation was performed with approval of the Boston University Medical Center IACUC and with the assistance of the Lab Animal Sciences Center and Transgenic Core Facility. High-grade chimeric mice with nearly 100% agouti coats were bred with wildtype (WT) C57BL/6 females to test for germline transmission of the targeted CK2α allele. F1 offspring were screened by PCR and Southern blot to identify heterozygous CK2α+/− mice. These were mated together to attempt to derive homozygous CK2α−/− offspring. Timed matings were performed and embryos were harvested to determine the developmental phenotypes. Fixed embryos were prepared for light and electron microscopic analysis and in situ hybridization as described [10, 14]. CK2 expression and activity were determined by in situ hybridization, immuno-blotting, and kinase assay using the CK2-specific peptide substrate RRREEETEEE (Sigma-Genosys) [15]. Background kinase activity in the absence of the peptide substrate was subtracted; P values were assessed by ANOVA, and Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons.

Fig. 2.

CK2α targeting strategy. A schematic of the targeted and endogenous alleles are shown (a), with the location of PCR primers that detect any recombination event (blue arrows) or homologous recombination (red arrows). These primers were used to screen pools and then individual clones; four clones that have been targeted homologously and selected in G418 and FIAU can be seen, numbers 7, 24, 30, 42 (b)

Whole mount in situ hybridization

For in situ hybridization, embryos were fixed in 4% para-formaldehyde/PBS, dehydrated, and stored at −20°C. Prior to hybridization, embryos were rehydrated, bleached in 6% H2O2, permeabilized with 10 μg/ml proteinase K, post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBT (1× PBS, 0.1% Tween), and pre-hybridized. Hybridization was performed at 70°C with digoxygenin-labeled probes transcribed from linearized plasmids (pBS-En-1 for engrailed-1, pSK75-T for brachyury, and pBS-mShh for mouse sonic hedgehog) using a DIG RNA Labeling Kit (Roche). After hybridization, embryos were washed, blocked in 10% lamb serum in PBT, and incubated with antibody in 10% lamb serum and PBT. Embryos were washed and treated with NBT/BCIP (4-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate) and postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% glutaraldehyde in PBS.

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

RNA was extracted with Trizol® (Invitrogen), DNAse I treated, and cDNA was prepared from 1 μg total RNA using the BioRad iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out in a 25 μl iTaq Sybr Green reaction (BioRad), in the presence of 400 nM of each primer in a Stratagene mx3000P real-time PCR machine. Primers included: En1_for (ACACAACCCTGCGATCCTAC); (GATATAGCGGTTTGCCTGGA); HPRT 5′ (GTTGGAT ACAGGCCAGACTTTGTTG); HPRT 3′ (GAGGGTAGG CTGGCCTATAGGCT); T_for (ATCAAGGAAGGCTTT AGCAAATGGG); and T_rev (GAACCTCGGATTCACA TCGTGAGA). Samples were analyzed in duplicate. Ct was determined for each sample, and copy number was determined using a standard formula: 10(Ct − 40)/ −3.32). When comparing samples, transcript copy number was normalized to the copy number for HPRT.

Results and discussion

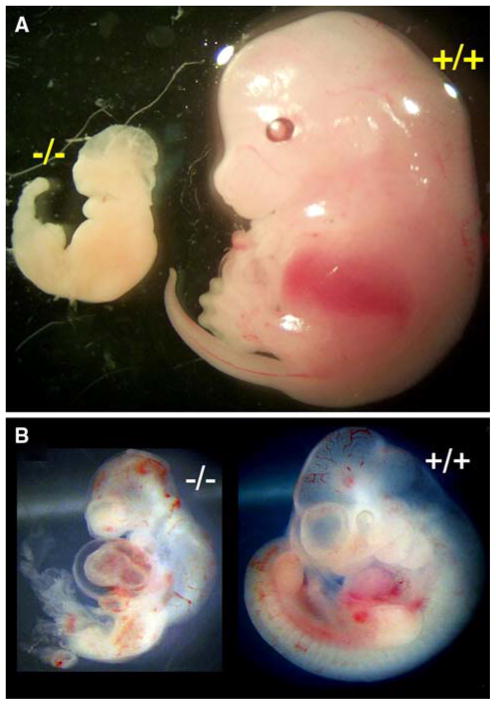

Electroporation and positive and negative selection of ES cells led to the identification of clones of cells that had acquired the targeted CK2α allele, in which the critical ATP-binding residue of CK2α at lysine 68 was replaced with a neomycin resistance cassette. These were identified by PCR and Southern blot (Fig. 2b). When clones were injected into blastocysts, high grade chimera were obtained. These were bred to obtain heterozygous CK2α+/− F1 mice. These mice were developmentally and histologically normal and fertile. However, crosses of these failed to yield any CK2α−/− offspring in more than 30 litters. The ratio of CK2α+/+ to CK2α+/− offspring was 1:2, consistent with the expected frequency for an embryonic lethal phenotype of CK2α−/− mice. Thus, timed matings were performed to generate embryos of varying genotypes and ages for analysis. No viable embryos were recovered beyond about e12.5; at e13.5 and e14.5, runted degenerating CK2α−/− embryos could be seen (Fig. 3a). Embryos up until e10.5 were viable. Some embryos were smaller and were found to have evidence of heart failure and pericardial edema (Fig. 3b) like the syndrome of hydrops fetalis that occurs with severe anemia or cardiac defects in humans. In examining earlier embryos, a variety of defects of the developing heart were noted (Fig. 4). In the CK2α−/− embryos, the formation of the four-chambered heart was markedly defective. An open heart tube persisted, with an enlarged endomyocardial cavity with a thin and disorganized endothelial lining with defective trabeculation and a thin atrial wall. The surface ectoderm and developing pericardium were also abnormal (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 3.

Abnormal CK2α−/− embryos. Since no viable CK2α−/− pups were found, timed matings were performed to determine the phenotype of the homozygous CK2α−/− embryos. Beyond about embryonic day 12.5, no viable embryos were found, but runted and degenerating embryos were seen (a, e14.5). Beginning at e10.5, the CK2α−/− embryos were smaller and some had evidence of heart failure, with a fluid-filled pericardium (b)

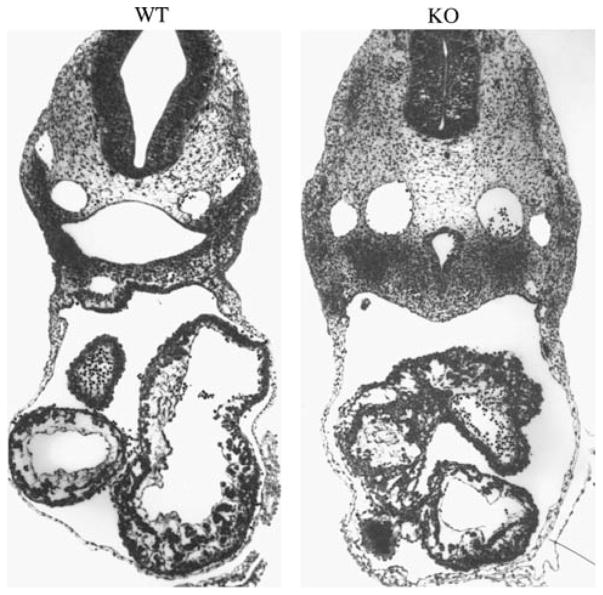

Fig. 4.

Cross sections of WT and KO embryos at e10.5 demonstrate the collapse of the open neural tube in the KO, top, and the delayed chambering and reduced trabeculation in the KO heart

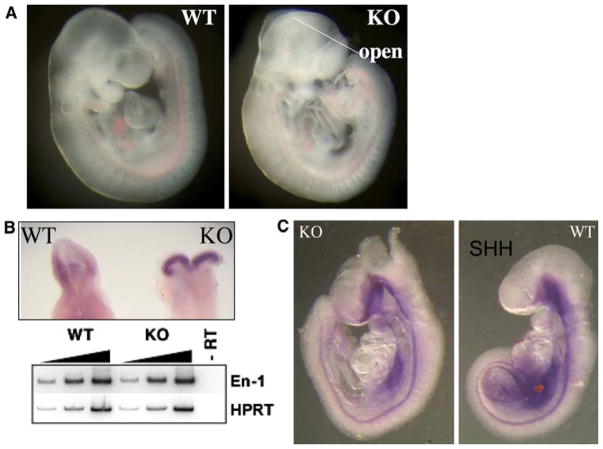

A second major phenotype was defects in the development of the neural tube and brain. In the CK2α−/− embryos, neural tube closure failed to occur at the level of the future midbrain in more than 90% of the CK2α−/− embryos; this was seen in 13% of heterozygous embryos and never observed in control WT embryos (Fig. 5a). Failure of neural tube closure does not interfere with specification of brain regions, as the homeobox gene engrailed-1 (En-1) mRNA was still expressed at the site of the midbrain/hindbrain junction by whole mount in situ hybridization (Fig. 5b). En-1 was similarly expressed in WT and KO embryos by both semiquantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5b) and quantitative real-time PCR (data not shown). The expression pattern and quantitative expression of sonic hedgehog mRNA, Shh, were also similar in WT and KO embryos, staining both the notochord and floorplate of the neural tubes (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Neural tube defects. By e9.5, the neural folds should have met and fused along the dorsum of the embryo, but in CK2α−/− embryos, this process fails, leading to collapse of the neural tube and failure of brain development to progress (compare WT and KO, panel a). The midbrain/hindbrain junction is delineated by in situ hybridization for En-1 mRNA (panel b, upper), which is expressed in similar levels by both semiquantitative RT-PCR (panel b, lower) and quantitative real-time PCR. The expression pattern and quantitative expression of sonic hedgehog mRNA, Shh, were also similar in WT and KO embryos, staining both the notochord and floorplate of the neural tubes (c)

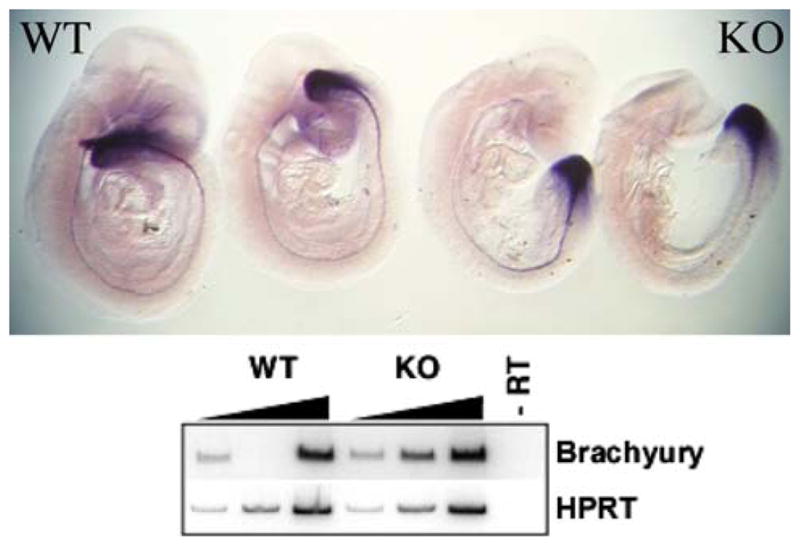

Abnormalities of tailbud development were seen in the CK2α−/− embryos, which typically had broadened shovel-shaped tails, that were well visualized by staining for the T-box gene brachyury (Fig. 6). Brachury was well-expressed in the abnormal tails, but at higher power, a reduction in anterior (cranial) staining for brachyury mRNA was visible. Additional phenotypes that were noted include underdevelopment of the limb buds, branchial arches, and otic and optic vesicles (not shown).

Fig. 6.

Abnormal tail bud morphology in the CK2α KO embryos. Embryos were stained for brachyury mRNA. As can be seen in the upper panel, the tails, where brachyury is heavily expressed, were broadened in the CK2α KO embryos compared to those of the WT embryos. A reduction in the anterior expression of brachyury can be appreciated at higher magnification. Overall expression is similar by both RT-PCR (lower panel) and quantitative real-time PCR

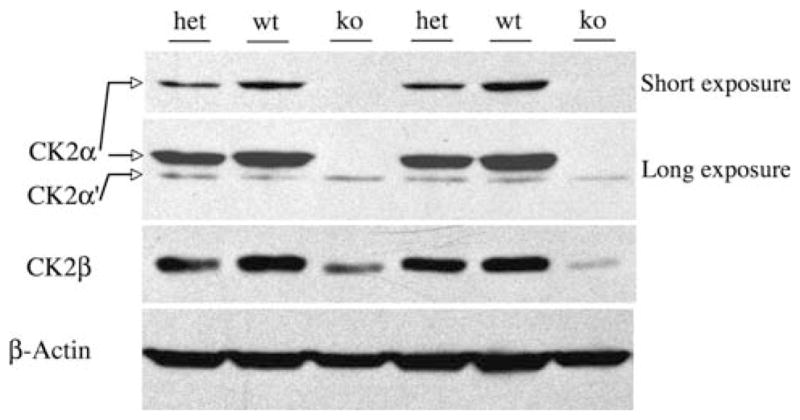

CK2α−/− knockout embryos were confirmed to have no CK2α mRNA or 42 kDa protein but had similar amounts of the 38 kDa CK2α′ protein as their littermate controls (Fig. 7), suggesting no compensatory mechanism of CK2α′ upregulation. Heterozygous CK2α+/− embryos had about half the CK2α protein as the WT embryos (Fig. 7). While expression of the CK2β subunit in the heterozygote and WT embryos was not strikingly different, the null embryos had reduced CK2β protein. This is similar to what has previously been observed in CK2α knock-down experiments, where CK2β mRNA were unchanged ([16], and data not shown). Interestingly, CK2β subunits are stabilized when integrated in the tetrameric holoenzyme [17], while free β subunits are ubiquitinated and subject to rapid proteosomal degradation [18]. In the null embryos, lack of CK2α could subject a greater free pool of CK2β subunit to degradation, leading to reduced steady state CK2β levels.

Fig. 7.

Alteration in CK2 subunit proteins in CK2α deficient embryos (e10.5). Two sets of embryos are shown, lanes 1–3 and 4–6. As can be seen in the short exposure of equally loaded embryonic proteins (top panel), CK2α protein expression is reduced in the CK2α+/− heterozygous embryos (het) and lost in the CK2α−/− KOs (ko), compared with wildtype CK2α+/+ (wt) mice. A longer exposure (second panel) confirms the absence of CK2α expression in the KOs and demonstrates that CK2α′ expression is similar in all genotypes. In the third panel, a reduction in CK2β protein is seen in the CK2α−/− KO embryos. The bottom panel shows the actin control blot for loading

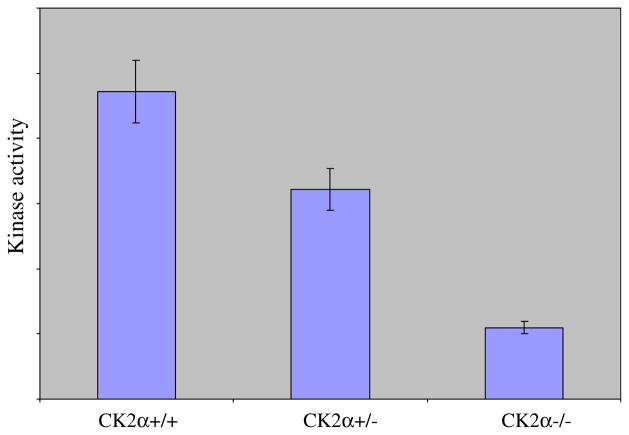

Kinase activity measurements on CK2α+/+, CK2α+/−, and CK2α−/− embryo littermates at e10.5 showed highest activity in the CK2α+/+ embryos, intermediate in the heterozygotes and lowest in the null embryos (Fig. 8); residual CK2 kinase activity in the KOs presumably reflects the presence of CK2α′, and expression of CK2α′ likely rescues expression during earlier embryogenesis.

Fig. 8.

Reduced CK2 kinase activity in CK2α+/− and CK2α−/− embryos (e10.5). Using the CK2 peptide substrate, kinase activity was reduced by 32% (P = 0.0002) in the heterozygous embryos and by 77% (P = 0.0001) in the homozygous deficient embryos, compared to wildtype. Residual CK2 activity is presumably due to the presence of the CK2α′ gene and protein

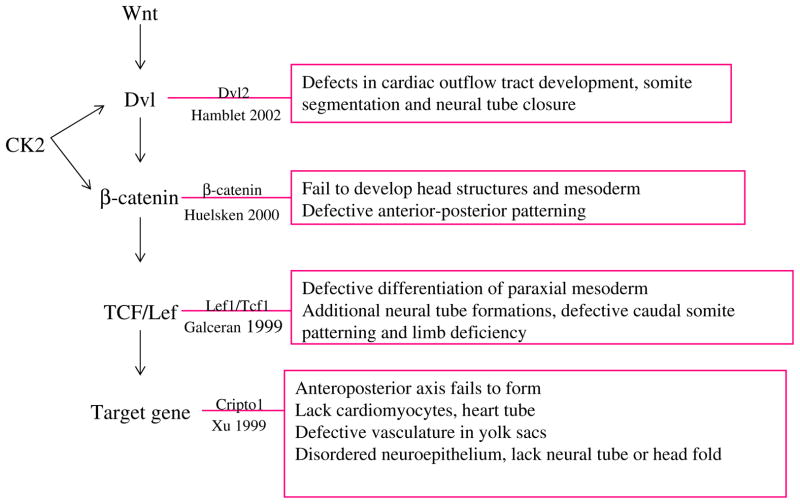

Preliminary data indicated that a variety of potential CK2 targets and pathways were disrupted in the CK2α−/− embryos, including abnormalities in Wnt pathway genes and proteins (I. Dominguez, unpublished data). These results are very provocative, because deletion of genes in the Wnt pathway also leads to defective development of brain and heart (Fig. 9). The Wnt transcriptional co-factor β-catenin is required for normal heart formation [19, 20], and the Wnt target cripto is required for differentiation of cardiogenesis and neural tube formation [21–24]. Wnt1 and Wnt3a are required for brain development [25–29]. The Wnt signaling intermediates of the dishevelled Dvl family are required for normal closure and apposition of the neural folds [6]. Thus, our data are consistent with the hypothesis that regulation of the Wnt pathway by CK2α is critical in mouse development, as it is in Xenopus laevis development [5, 8]. This hypothesis will be validated in future molecular experiments and through rescue experiments designed to determine whether the CK2α−/− knockout phenotypes can be complemented by expression of elements of the Wnt pathway.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of CK2 knockout defects and Wnt pathway knockout defects, with a schema to indicate where in the pathway CK2 is believed to act. Both Dvl and β-catenin have been shown to be direct CK2 targets, and thus loss of CK2 is predicted to lead to downregulation of Dvl, β-catenin, and downstream Wnt signaling. Defects of embryos in which Dvl2 [30], β-catenin [19], the transcription factor Lef1/ Tcf1 [31], and the putative Wnt target gene Cripto1 [21] are described

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge highly skilled technical assistance in carrying out these studies from Jessica Murray and Julie Cha, Patrick Hogan who maintains the mouse colony, and Greg Martin of the Transgenic Core at Boston University Medical Center. We are grateful to T. Yamaguchi for providing plasmids used for in situ hybridization. This work was supported by N.I.H. R01 CA71796 to David C. Seldin as well as Project 2 of P01 ES011624 (G. Sonenshein, P.I.), a Scientist Development Award from the American Heart Association (0735521T) to Isabel Dominguez, a pre-doctoral fellowship to David Y. Lou through N.I.H. T32 CA064070 (Oncobiology Training Program at Boston University School of Medicine), and a Department of Medicine Pilot Grant to Isabel Dominguez.

Contributor Information

David C. Seldin, Email: dseldin@bu.edu, Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, 650 Albany Street, Boston, MA 02118, USA

David Y. Lou, Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, 650 Albany Street, Boston, MA 02118, USA

Paul Toselli, Department of Biochemistry, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, 650 Albany Street, Boston, MA 02118, USA.

Esther Landesman-Bollag, Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, 650 Albany Street, Boston, MA 02118, USA.

Isabel Dominguez, Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, 650 Albany Street, Boston, MA 02118, USA.

References

- 1.Seldin DC, Leder P. Casein kinase II alpha transgene-induced murine lymphoma: relation to theileriosis in cattle. Science. 1995;267:894–897. doi: 10.1126/science.7846532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landesman-Bollag E, Romieu-Mourez R, Song DH, et al. Protein kinase CK2 in mammary gland tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20:3247–3257. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song DH, Dominguez I, Mizuno J, et al. CK2 phosphorylation of the armadillo repeat region of beta-catenin potentiates Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24018–24025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song DH, Sussman DJ, Seldin DC. Endogenous protein kinase CK2 participates in Wnt signaling in mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23790–23797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909107199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dominguez I, Mizuno J, Wu H, et al. Protein kinase CK2 is required for dorsal axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol. 2004;274:110–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S, Jones KA. CK2 controls the recruitment of Wnt regulators to target genes in vivo. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2239–2244. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Y, Wang HY. Casein kinase 2 is activated and essential for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(27):18394–18400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez I, Mizuno J, Wu H, et al. A role for CK2alpha/ beta in Xenopus early embryonic development. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;274:125–131. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-3073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchou T, Vernet M, Blond O, et al. Disruption of the regulatory beta subunit of protein kinase CK2 in mice leads to a cell-autonomous defect and early embryonic lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:908–915. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.908-915.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X, Toselli PA, Russell LD, et al. Globozoospermia in mice lacking the casein kinase II alpha’ catalytic subunit. Nat Genet. 1999;23:118–121. doi: 10.1038/12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lou DY, Dominguez I, Toselli P, et al. The alpha catalytic subunit of protein kinase CK2 is required for mouse embryonic development. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:131–139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01119-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansour SL, Thomas KR, Capecchi MR. Disruption of the proto-oncogene int-2 in mouse embryo-derived stem cells: a general strategy for targeting mutations to non-selectable genes. Nature. 1988;336:348–352. doi: 10.1038/336348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng CX, Wynshaw-Boris A, Shen MM, et al. Murine FGFR-1 is required for early postimplantation growth and axial organization. Genes Dev. 1994;8:3045–3057. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toselli P, Faris B, Sassoon D, et al. In-situ hybridization of tropoelastin mRNA during the development of the multilayered neonatal rat aortic smooth muscle cell culture. Matrix. 1992;12:321–332. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Litchfield DW, Arendt A, Lozeman FJ, et al. Synthetic phosphopeptides are substrates for casein kinase II. FEBS Lett. 1990;261:117–120. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seldin DC, Landesman-Bollag E, Farago M, et al. CK2 as a positive regulator of Wnt signalling and tumourigenesis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;274:63–67. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-3078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luscher B, Litchfield DW. Biosynthesis of casein kinase II in lymphoid cell lines. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:521–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang C, Vilk G, Canton DA, et al. Phosphorylation regulates the stability of the regulatory CK2beta subunit. Oncogene. 2002;21:3754–3764. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huelsken J, Vogel R, Brinkmann V, et al. Requirement for beta-catenin in anterior-posterior axis formation in mice. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:567–578. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liebner S, Cattelino A, Gallini R, et al. Beta-catenin is required for endothelial-mesenchymal transformation during heart cushion development in the mouse. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:359–367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu C, Liguori G, Persico MG, et al. Abrogation of the Cripto gene in mouse leads to failure of postgastrulation morphogenesis and lack of differentiation of cardiomyocytes. Development. 1999;126:483–494. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu C, Liguori G, Adamson ED, et al. Specific arrest of cardiogenesis in cultured embryonic stem cells lacking Cripto-1. Dev Biol. 1998;196:237–247. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morkel M, Huelsken J, Wakamiya M, et al. Beta-catenin regulates Cripto- and Wnt3-dependent gene expression programs in mouse axis and mesoderm formation. Development. 2003;130:6283–6294. doi: 10.1242/dev.00859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding J, Yang L, Yan YT, et al. Cripto is required for correct orientation of the anterior-posterior axis in the mouse embryo. Nature. 1998;395:702–707. doi: 10.1038/27215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nusse R, Varmus HE. Wnt genes. Cell. 1992;69:1073–1087. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90630-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mastick GS, Fan CM, Tessier-Lavigne M, et al. Early deletion of neuromeres in Wnt-1−/− mutant mice: evaluation by morphological and molecular markers. J Comp Neurol. 1996;374:246–258. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961014)374:2\246::AID-CNE7[3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMahon AP, Bradley A. The Wnt-1 (int-1) proto-oncogene is required for development of a large region of the mouse brain. Cell. 1990;62:1073–1085. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90385-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMahon AP, Joyner AL, Bradley A, et al. The midbrain-hindbrain phenotype of Wnt-1-/Wnt-1-mice results from stepwise deletion of engrailed-expressing cells by 9.5 days postcoitum. Cell. 1992;69:581–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90222-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takada S, Stark KL, Shea MJ, et al. Wnt-3a regulates somite and tailbud formation in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1994;8:174–189. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamblet NS, Lijam N, Ruiz-Lozano P, et al. Dishevelled 2 is essential for cardiac outflow tract development, somite segmentation and neural tube closure. Development. 2002;129:5827–5838. doi: 10.1242/dev.00164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galceran J, Hsu SC, Grosschedl R. Rescue of a Wnt mutation by an activated form of LEF-1: regulation of maintenance but not initiation of Brachyury expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8668–8673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151258098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]