Summary

We previously showed that antigen immunization in the presence of the immunosuppressant dexamethasone (a strategy we termed “suppressed immunization”) could tolerize established recall responses of T cells. However, the mechanism by which dexamethasone acts as a tolerogenic adjuvant has remained unclear. In the present study, we show that in the spleen and peripheral lymph nodes, dexamethasone dose-dependently enriches CD11cloCD40lo macrophages by depleting all other CD11c+CD40+ cells including dendritic cells. The enriched macrophages display a distinct MHC IIloCD86hi phenotype. Upon activation by a recall antigen in vivo, they upregulate IL-10, a classic marker for tolerogenic antigen-presenting cells, and elicit a serum IL-10 response. When presenting a recall antigen in vivo, they do not elicit recall responses of memory T cells, but rather stimulate the expansion of antigen-specific regulatory T cells. Moreover, depletion of CD11cloCD40lo macrophages during suppressed immunization diminishes the latter’s tolerogenic efficacy. These results indicate that dexamethasone acts as a tolerogenic adjuvant partly by enriching the CD11cloCD40lo tolerogenic macrophages.

Keywords: Tolerance, Dexamethasone, Macrophage

Introduction

Immunization remains to be the most effective means to manipulate Ag-specific immune responses. However, it is difficult to use immunization to attenuate established pathological responses responsible for autoimmune disease, allergy, or graft rejection, because immunogens can trigger memory responses of pathogenic T cells and actually worsen the diseases.

Adjuvants have long been used in immunization to alter the host immune responses to immunogens [1]. In theory, adjuvants can encompass both immunogenic agents that potentiate immunity and tolerogenic agents that potentiate tolerance. However, all adjuvants in use today are immunogenic. To search for “tolerogenic adjuvants,” we have looked to immunosuppressants that are capable of doing at least two things: inhibiting memory responses of pathogenic T cells and promoting tolerogenic antigen presentation by APCs.

The synthetic glucocorticoid immunosuppressant dexamethasone (Dex) is particularly interesting because previous in vivo studies showed that Dex preferentially induced apoptosis of effector T cells while sparing regulatory T cells [2, 3]. Moreover, in vitro studies, performed mostly in cultured dendritic cells (DCs), showed that Dex altered the phenotype and function of DCs, rendering them tolerogenic [4]. With both of these effects in mind, we tested Dex as a tolerogenic adjuvant by combining it with Ags during immunization (we named this strategy “suppressed immunization”). In mouse models of delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) and type I diabetes, we showed that Dex, when combined with peptide Ags, caused expansion of Ag-specific CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) that persisted in vivo and led to long-term desensitization of established DTH and prevention of autoimmune diabetes, respectively [5].

Despite these intriguing results, the mechanism of action by Dex as an adjuvant remains unclear. Particularly, we wanted to know what type of tolerogenic DCs is induced by Dex in vivo. To that end, we have systemically examined the changes of DC populations in Dex-treated mice. To our surprise, Dex actually depletes all DCs in the spleen and peripheral LNs; yet, it enriches a subset of macrophages that functions as tolerogenic APCs. Our study thus reveals that Dex’s adjuvant mechanism involves in vivo selection of tolerogenic macrophages.

Results

Dex enriches CD11clo cells in the spleen and LNs by depleting CD11chi cells

Because Dex had been shown to induce tolerogenic DCs in vitro [4], we reasoned that Dex might exert its adjuvant effect by inducing tolerogenic DCs in vivo. However, Dex had also been shown to deplete the majority of DCs in vivo by causing redistribution and apoptosis of the cells [6, 7]. Accordingly, we hypothesized that Dex might selectively deplete non-tolerogenic DCs in vivo while retaining tolerogenic DCs, which in turn contribute to the expansion of Ag-specific Treg we observed previously [5].

To test this hypothesis, we analyzed CD11c+ cells in Dex-treated mice. CD11c had long been used as a DC marker. Moreover, in the spleen and LNs of Balb/c mice (Supporting Information Fig. 1) and C57BL/6 mice (not shown), nearly all the MHC II+ cells after excluding B cells were CD11c+; therefore, the CD11c+ cells likely contained the tolerogenic APCs we were looking for, even if they were not DCs.

Balb/c mice were injected (s.c.) with a pharmacological dose of Dex (4.5 mg/kg). A day later, DCs in the spleen, peripheral LNs, and blood were analyzed by flow cytometry. We differentiated various DCs by CD11c/CD40 double staining [8, 9]. We detected two major CD11c+CD40+ cell populations in the spleen and four major populations in pooled subcutaneous LNs (Fig. 1). We also detected one major population in the blood (Fig. 1). Intriguingly, in both the spleen and LNs, Dex depleted the cells in all of the populations except for a CD11cloCD40lo population. Dex also depleted the single population in the blood; the latter was therefore not further studied. Similar results were obtained in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1), indicating that the described observation was not peculiar to the Balb/c strain.

Figure 1.

Dex enriches CD11clo cells in the spleen and LNs by depleting CD11chi cells. Balb/c or C57BL/6 mice (n = 3) were injected (s.c.) with PBS (“NT”) or 4.5 mg/kg of Dex; 1 day later, splenocytes, pooled LN cells, and blood leukocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry. T cells (CD11c−CD40−) and B cells (CD11c−CD40hi) were gated out, except for an arbitrary small portion used as internal controls for CD11c and CD40 staining. Shown is 1 of 3 experiments with similar results. Major CD11c+CD40+ populations are circled. Total CD11c+CD40+ cells are gated by R2, of which the CD11cloCD40lo population is gated by R3. Numbers in parentheses indicate percentages of R1 (live)-gated cells. a, dermis-derived DCs; b, Langerhans cells; c, CD11b+ DCs.

Based on their sensitivity to Dex, we divided the CD11c+CD40+ cells in the spleen and LNs into two populations. One consisted of CD11cloCD40lo cells (referred to hereafter as “CD11clo” cells), which were retained after the Dex treatment; the other included the rest of the CD11c+CD40+ cells, mostly CD11cint and CD11chi cells with varying CD40 levels (referred to hereafter as “CD11chi” cells), which were depleted by Dex. Further experiments showed that, at Dex doses of 0.5 –4.5 mg/kg, the CD11clo cells were resistant to Dex, whereas the CD11chi cells were sensitive (Supporting Information Fig. 2A). At Dex doses > 4.5 mg/kg, the absolute number of the CD11clo cells started to drop, but they were still more resistant to Dex than were the CD11chi cells. As a result, the ratio of CD11clo cells to CD11chi cells in the spleen continued to increase until the dose reached 13.5 mg/kg; and the ratio in the LNs peaked at about 10 mg/kg (Supporting Information Fig. 2A). Based on this observation, we used Dex at 4.5 mg/kg for all in vivo experiments thereafter to preserve the CD11clo cells.

We also found that following a single injection of Dex at 4.5 mg/kg, the resulting “CD11chi cell-depleting” effect in both the spleen and LNs lasted 4 days, peaking between 1 – 2 days (Supporting Information Fig. 2B). We also confirmed that the preferential depletion of the CD11chi cells was mediated by the glucocorticoid receptor, because it could be completely abolished by mifepristone, a specific blocker of the glucocorticoid receptor (Supporting Information Fig. 2C). Lastly, we showed that Dex did not downregulate the expression of CD11c on isolated CD11chi cells in vitro (Supporting Information Fig. 2D). Therefore, it was unlikely that it enriched CD11clo cells in vivo by converting them from CD11chi cells.

Dex-enriched CD11clo cells are monocyte-derived macrophages

To determine whether Dex-enriched CD11clo cells were DCs, we analyzed their lineage markers. In the LNs, these cells were Ly6CloCD62Llo (monocytes) [10] and CCR7− (blood-borne) (Fig. 2A), which matched the phenotype of the monocyte-derived DCs described by Nakano et al. [9]. Unexpectedly, these cells also expressed the macrophage markers F4/80 and CD68 (Fig. 2A), which indicated that they were actually monocyte-derived macrophages. On the other hand, the Dex-depleted CD11chi cells included dermis-derived DCs, the Langerhans cells, and CD11b+ DCs (marked as a, b, and c in Fig. 1, respectively), all of which had been described by Nakano et al. [9].

Figure 2.

Dex-enriched CD11clo cells are monocyte-derived macrophages. Balb/c mice (n = 3) were injected with PBS (“NT”) or Dex (4.5 mg/kg); 1day later, pooled LN cells and splenocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry. Solid line, specific staining for the indicated marker; dotted line, isotype control. (A) Expression of various markers in the LN and spleen cells. CD11clo cells and CD11chi cells were gated by R3 and R2 –R3 (depicted in Fig. 1), respectively. (B) Depletion by Dex of spleen pDCs from the CD11clo population. CD11clo cells and CD11chi cells were separately gated. (C) Depletion of spleen cDCs by Dex. Total CD11c+ cells were gated. Shown in each panel is 1 of 3 or more experiments with similar results.

In the spleen, Dex-enriched CD11clo cells also expressed the Ly6CloCD62Llo monocyte marker; however, they were not identical to the CD11clo cells in LNs because they appeared to have differentiated further into macrophages (F4/80hi CD68hi) (Fig. 2A). This phenotype matches that of the red pulp macrophages [11–13]. Prior to injection of Dex, splenic CD11clo cells contained a small population of PDCA-1+ cells (Fig. 2B), representing plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) [14]. These pDCs were eliminated after injection of Dex (Fig. 2B), which was consistent with previous reports [6, 7]. As a result, the Dex-enriched splenic CD11clo cells were essentially all F4/80hi CD68hi macrophages (Fig. 2A).

In contrast, Dex-depleted splenic CD11chi cells were mostly CD62L−CD68− (Fig. 2A) and contained nearly all the CD4+ and CD8+ populations (Fig. 2C) known to be splenic conventional DCs (cDCs) [15, 16]. Histological analysis further showed that the spleen from Dex-injected mice lacked cells with intense CD11c staining (Supporting Information Fig. 2E), which confirmed that rather than depleting all CD11c+ cells, Dex selectively depleted CD11chi cells. Collectively, these results showed that Dex enriched CD11lo macrophages (referred to hereafter as “Dex-MΦs”) in the spleen and LNs by depleting both cDCs and pDCs.

Dex-MΦs display the phenotype of tolerogenic APCs

We then tested the hypothesis that Dex-MΦs may be the tolerogenic APCs that mediate suppressed immunization. As a first step, we analyzed the functional markers on these cells. Expression of MHC II and CD86 is indicative of the ability of an APC to activate T cells via antigenic and costimulatory signals, respectively. Compared with untreated CD11chi cells (cDCs) from naïve mice, Dex-MΦs in both the spleen and LNs expressed a higher level of CD86, but a lower level of MHC II (Fig. 2A). Indeed, whereas the CD86 expression was relatively unaffected by increasing Dex dose, the MHC II expression was decreased in a Dex dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 3A). Analysis of additional markers further showed that Dex-MΦs also displayed a lower level of the maturation marker CD83 and a higher level of the phagocytosis marker CD68 (Fig. 2A). However, an in vivo bead uptake assay did not detect enhanced phagocytosis by these cells compared with control CD11clo macrophages (Supporting Information Fig. 3). This indicated that the upregulation of the CD68 marker by Dex did not necessarily increase the phagocytotic activity of Dex-MΦs. Collectively, the overall phenotype of Dex-MΦs resembled that of poorly immunogenic and immature APCs.

Figure 3.

Dex-MΦs display the phenotype of tolerogenic APCs. (A) Balb/c mice (n ≥ 3 per dose point) were injected with various doses of Dex; 1 day later, splenocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry for each mouse. CD11clo cells were gated. Regression curves were plotted with the Sigmaplot software. Shown is 1 of 3 experiments with similar results. Open circle, CD86; filled circle, MHC II. (B) Four groups of OVA-sensitized Balb/c mice (n = 3) were each injected with Dex alone (4.5mg/kg, s.c., on day 1), OVA323-339 peptide alone (50 μg/mouse, i.v., on day 2), both Dex (on day 1) and the peptide (on day 2), or neither. On day 3, splenocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry. CD11cloF4/80hi cells were gated. Shown is 1 of 2 experiments with similar results. Thick line, specific staining for the indicated marker; thin line, isotype control. (C) Splenocytes from the same set of mice in (B) were analyzed for intracellular IL-10 by flow cytometry. CD11cloF4/80hi cells were gated. Shown is 1 of 3 experiments with similar results. Thin line, NT; dotted line, Dex; dashed line, peptide; thick line, Dex + peptide. (D –F) OVA-sensitized Balb/c mice were divided into groups (n = 3); each group was injected with the indicated agents, as described in panel B. Clodronate liposomes (Clo) were given intravenously at 100 μl/mouse on day 1. Blood samples were taken from all groups on day 3. Serum IL-10 and IL-12 (p70 heterodimer) levels were analyzed by ELISA (R&D Systems). The results were expressed as pg/ml of serum. Shown in each panel are the combined results of 2 or more separate experiments (mean ± SD). The difference between the Dex + peptide combination group and any of the other groups is statistically significant (p < 0.001 by Student’s t test). Filled bar, IL-10; open bar, IL-12.

Because Dex-MΦs from the spleen and LNs displayed similar functional markers and the former could be isolated in relatively larger numbers, we used the former to further determine whether Dex-MΦs could function as tolerogenic APCs. First, we examined the response of Dex-MΦs to recall Ag stimulation in vivo, using the same DTH model that we had used to demonstrate the adjuvant effect of Dex [5]. In this model, Balb/c mice were presensitized with hen ovalbumin (OVA); then, the mice were injected with Dex (to generate Dex-MΦs) and the I-Ad-restricted dominant epitope OVA323–339 (to reactivate memory T cells), either alone or in combination. Flow cytometry was then performed on splenic CD11clo cells. The result showed that the cells in all groups expressed similar levels of MHC I, CD80, CD86, or PD-L1 (Supporting Information Fig. 4). The only difference noted was in the level of MHC II (Fig. 3B). Compared with those in non-treated mice, the CD11clo cells in Dex-treated mice (i.e. Dex-MΦs) downregulated MHC II. In contrast, the CD11clo cells in OVA323–339-treated mice markedly upregulated MHC II; however, such recall Ag-induced upregulation of MHC II was abolished in mice treated with both Dex and the recall Ag. These results echoed the downregulation by Dex of the MHC II expression shown in Fig. 3A.

Importantly, in mice treated with both Dex and the recall Ag, the CD11clo cells upregulated IL-10 (Fig. 3C), a signature cytokine for tolerogenic APCs [17]. This result indicated that Dex-MΦs became tolerogenic in vivo upon recall Ag stimulation and that the event was recall Ag-dependent.

Upon the induction of IL-10-producing Dex-MΦs, we also detected a rise of IL-10 in blood (Fig. 3D), which depended not only on Dex and the recall Ag, but also on preexisting immunological memory because it was absent in mice that had not been presensitized with OVA (Fig. 3E). Concomitantly, we detected a fall of the IL-12 p70 heterodimer, a signature cytokine for immunogenic APCs, which depended solely on Dex (Fig. 3D). Taken together, the change of the IL-10:IL-12 balance pointed to an altered memory response involving increased tolerogenicity in APCs.

We next determined whether macrophages were the APCs responsible for the serum cytokine response. To that end, the mice were treated with an intravenous injection of clodronate liposomes, known to selectively deplete macrophages in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow where the liposomes could enter extravascular tissue through sinusoids [18]. We first confirmed that a single injection of clodronate liposomes containing 50 μg of clodronate depleted > 90% of CD11clo macrophages in the spleen (Supporting Information Fig. 5A), whereas CD11chi cDCs and CD11clo pDCs were not affected (Supporting Information Fig. 5, B & C), nor were LN macrophages (data not shown).

As shown in Fig. 3F, the serum IL-10 response was completely abolished by the depletion of macrophages via clodronate liposomes. In contrast, the fall of serum IL-12, which was shown to be caused by Dex in Fig. 3D, was not affected by clodronate liposomes, neither was the stimulatory effect of the recall Ag on IL-12. These results indicated that the clodronate-sensitive macrophages (which included the CD11clo subset), while eliciting the IL-10 response upon recall stimulation, were not a significant source of serum IL-12.

In aggregate, these results suggested that following the injection of both Dex and the recall Ag into the pre-sensitized mice, Dex not only enriched macrophages, but also potentiated their differentiation into IL-10-producing APCs in response to recall stimulation. Concomitantly, Dex also inhibited the production of IL-12 by non-macrophage APCs, which led to a more tolerogenic cytokine milieu.

Dex-MΦs function as tolerogenic APCs

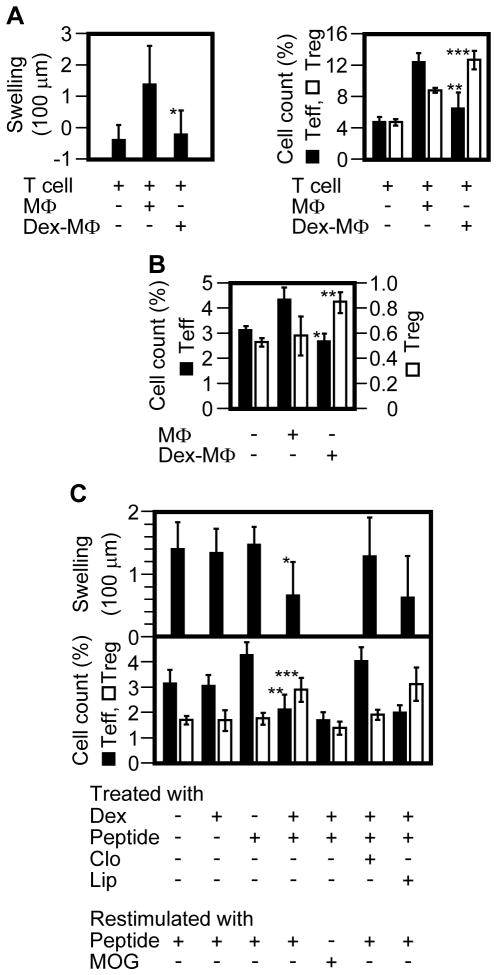

We determined whether Dex-MΦs were actually tolerogenic in vivo using a second DTH model. In this model, memory CD4+ T cells (donor T cells) were isolated from Balb/c Foxp3-eGFP mice that had been presensitized with OVA; Ag-primed CD11clo cells (donor APCs) were isolated from wild-type Balb/c mice that had been presensitized with OVA and freshly injected (restimulated) with OVA323-339. Then, the donor T cells and donor APCs were co-injected into a footpad of naïve Balb/c mice; this resulted in transfer of DTH, as assessed by footpad swelling (Fig. 4A). However, when Dex-MΦs were used as donor APCs, there was no transfer of DTH, which indicated that Dex-MΦs lacked the ability to reactivate memory T effectors (Teff). When we examined recall activation of the donor T cells in the draining (popliteal) LN, we found that control CD11clo cells preferentially stimulated the proliferation of donor Teff, whereas Dex-MΦs preferentially stimulated donor Treg (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Dex-MΦs function as tolerogenic APCs. (A) Donor T cells (eFluor 670-labeled CD4+ T cells from OVA-sensitized Balb/c Foxp3-eGFP mice) and donor APCs (Ag-primed Dex-MΦs or Ag-primed control MΦs) were co-injected (s.c.) into a footpad of naïve Balb/c mice. At 24 h, DTH was measured by footpad swelling (left panel). On day 4, the draining LN cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (right panel). Donor memory T cells (CD3+CD44+eFluor 670+) were gated, of which the percentages of proliferating Teff (eFluor670loGFP−) vs. Treg (eFluor670loGFP+) were determined. Shown are the combined results of 2 separate experiments involving a total of 6 mice per group (mean ± SD). Cell count (%) indicates the relative number of proliferating Teff or Treg within donor memory T cells. Filled bar, Teff; open bar, Treg. *, p = 0.04; **, p = 0.006; ***, p = 0.005 (all between the Dex-MΦ group and the MΦ group; Student’s t test). (B) Ag-primed MΦs or Ag-primed Dex-MΦs were injected (i.v.) into OVA-sensitized Foxp3-eGFP mice (n = 3) on day 1. BrdU was injected (i.p.) on day 3; 12 hrs later, splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated from the mice and analyzed by flow cytometry. Memory T cells (CD3+CD44+) were gated, of which the percentages of proliferating Teff (BrdU+GFP−) vs. Treg (BrdU+GFP+) were determined. Shown is 1 of 2 experiments with similar results (mean ± SD). Cell count (%) indicates the relative number of proliferating Teff or Treg within memory CD4+ T cells. Filled bar, Teff; open bar, Treg. *, p = 0.007; **, p = 0.04 (all between the Dex-MΦ group and the MΦ group; Student’s t test). (C) OVA-sensitized Balb/c mice (n = 5) were treated as indicated, and DTH was rechecked 2 month later (upper panel). One month after that, the mice were restimulated twice (i.v.) with 50 μg of OVA323-339 or a control peptide, MOG, on days 1 and 3. Of note, group 4 (from the left) of the top panel was divided into 2 subgroups (the lower panel, groups 4 and 5 from the left) during restimulation. BrdU were injected (i.p.) on day 3; 12 hrs later, splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated, immunostained for CD3, CD44, Foxp3, and BrdU, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Memory T cells (CD3+CD44+) were gated, of which the percentages of proliferating Teff (BrdU+Foxp3−) vs. Treg (BrdU+ Foxp3+) were determined (lower panel). Shown is 1 of 2 experiments (mean ± SD). Cell count (%) indicates the relative number of proliferating Teff or Treg within memory CD4+ T cells. Filled bar, Teff; open bar, Treg; Clo, clodronate liposomes; Lip, control liposomes; *, p = 0.002; **, p = 0.04; ***, p = 0.01 [all between column 1 (nontreated) and column 4 (suppressed immunization); Student’s t test].

We substantiated this finding by further demonstrating the ability of Dex-MΦs to expand endogenous Ag-specific Treg. To that end, Ag-primed control CD11clo cells or Ag-primed Dex-MΦs were intravenously transferred into OVA-sensitized Foxp3-eGFP mice. Proliferation of endogenous memory T cells in the spleen was then determined by BrdU incorporation (Fig. 4B). Again, while the control CD11clo cells preferentially stimulated Teff, Dex-MΦs preferentially stimulated Treg.

Having shown that the Dex-MΦs could induce Treg responses, we next evaluated their role in suppressed immunization by assessing whether depleting macrophages could reduce the efficacy of the regimen in attenuating established DTH. A single intravenous injection of clodronate liposomes depleted > 90% of CD11clo macrophages in the spleen between days 1 – 4; by day 7, < 40% of the cells were recovered (Supporting Information Fig. 5C). Thus, a single injection of clodronate liposomes was sufficient to deplete the macrophages for the duration of an entire regimen of suppressed immunization (7 days).

Suppressed immunization combining Dex with OVA323–339 attenuated established OVA-specific DTH and induced preferential expansion of OVA323–339-specific Treg over Teff, as assessed again by BrdU incorporation (Fig. 4C). However, when macrophages were depleted by clodronate liposomes, both the DTH-attenuating and Treg-inducing effects of the immunization were abolished. These results indicated that the efficacy of suppressed immunization was, at least partly, dependent on macrophages.

Besides the spleen, liver and bone marrow also harbor macrophages. To assess the involvement of liver and bone marrow macrophages in suppressed immunization, we analyzed their response to Dex and clodronate liposomes. The liver macrophages, identified as MHC II+F4/80+ cells, had been previously shown to be sensitive to Dex [19]. Indeed, they were depleted following a single injection of Dex at 4.5 mg/kg (Fig. 5A); therefore, they were essentially absent during suppressed immunization regardless of the use of clodronate liposomes. In contrast, bone marrow macrophages, also identified as MHC II+F4/80+ cells, were resistant to Dex but sensitive to clodronate liposomes (Fig. 5A). However, these cells showed the CD11cloCD40lo phenotype (Fig. 5B), which indicated that they too were Dex-MΦs. Because clodronate liposomes had been shown to abolish the efficacy of suppressed immunization (Fig. 4C), the identification of clodronate liposome-sensitive Dex-MΦs in the bone marrow pointed to their possible contribution to the efficacy of suppressed immunization.

Figure 5.

Effect of clodronate liposomes on suppressed immunization may involve bone marrow, but not liver, macrophages. (A) Balb/c mice were injected with the indicated agents. At 16 h, the liver and bone marrow cells were isolated, immunostained for MHC II and F4/80, and the MHC II+F4/80+ cells (macrophages) were counted by flow cytometry as a percentage of total live-gated liver or bone marrow cells (mean ± SD). Cell count (%) indicates the relative number of MHC II+F4/80+ cells in total liver or bone marrow cells. The difference between the Dex group and the control group (left panel) and that between the Clo group and any of the other groups (right panel) are statistically significant (p < 0.0001 by Student’s t test). (B) Bone marrow cells from Dex-treated mice were immunostained for MHC II, F4/80, CD11c, and CD40 and analyzed by flow cytometry. MHC II+F4/80+ cells were gated (R2) and analyzed in comparison with the cells outside of R2 (i.e. “- R2”). CD11cloCD40lo cells are indicated. Shown in each panel is 1 of 3 or more experiments with similar results.

In summary, the results from both the adoptive transfer of Dex-MΦs (the “gain of function” approach) and the depletion of Dex-MΦs (the “loss of function” approach) indicated that Dex-MΦs are tolerogenic.

Discussion

Dex had been previously shown to induce tolerogenic DCs and macrophages in vitro. However, little was known about its action as a tolerogenic adjuvant in vivo [4, 20, 21]. The present study shows that Dex affects CD11c+CD40+ DCs and macrophages in vivo via multiple mechanisms. First, Dex selectively depletes cDCs and pDCs and, thus, systemically alters the balance between DCs and macrophages in favor of the latter, causing the predominance of the CD11cloCD40lo subset of macrophages (Dex-MΦs) in the spleen and LNs. This may allow the Dex-MΦs to act as de facto APCs during suppressed immunization. Second, Dex increases the tolerogenicity of Dex-MΦs by downregulating MHC II, and by upregulating IL-10 upon recall Ag stimulation. Interestingly, the upregulation of IL-10 is recall Ag- and memory-dependent, which suggests that Dex may be more effective at tolerizing established immune responses than preventing their initiation. Last, Dex-MΦs mediate a serum IL-10 response to recall Ags. This, in conjunction with Dex-mediated downregulation of IL-12, yields a cytokine milieu conducive to the induction of tolerance. These mechanisms explain why suppressed immunization, which requires Dex as the adjuvant, depends on macrophages.

These mechanisms, however, do not exclude the possibility that depletion of CD11chi cells (i.e. DCs) may also contribute to the tolerogenic effect of Dex. Particularly, we have shown that depletion of the CD11clo macrophages do not significantly affect the level of IL-12 (Fig. 3E); thus, it is likely that the DCs may be the main source of serum IL-12. If this is the case, depleting the DCs during recall stimulation can dampen recall responses.

The results of this study pose several new questions. Considering the early finding that Treg are more resistant to Dex than Teff [2, 3], what is the common basis for the resistance to Dex in Treg and macrophages? It has been reported that mice, like men, express two alternatively spliced glucocorticoid receptor isoforms, GRα and GRβ [22]. GRα mediates most of the classic actions of the glucocorticoids, including immunosuppression; whereas GRβ acts as a dominant-negative modifier of GRα. Thus, the simplest reason for the resistance to Dex might be an intrinsically lower level of GRα and/or a higher level of GRβ. We are currently testing this hypothesis.

Another question is how Dex-MΦs promote a Treg response during suppressed immunization. Upon recall Ag stimulation, Dex-MΦs produce IL-10, which may promote Treg-biased responses by suppressing the immunogenicity of Teff and by activating additional IL-10-responsive tolerogenic cells [23]. Particularly with regard to the latter, we should be able to identify them by their resistance to Dex and activation by IL-10. That being said, the effects of IL-10 are not Ag-specific and, as such, cannot account for the expansion of Treg in an Ag-specific manner during suppressed immunization. The MHC IIloCD86hi phenotype may be more relevant in that respect. It is known that strong TCR stimulation, which tends to activate the Akt/PI3K/mTOR pathway, antagonizes the induction of Foxp3 and disfavors the generation of Treg; weak TCR stimulation on the other hand favors the generation of Treg [24–26]. Moreover, only the Treg that are expanded with high-avidity Ags presented at low densities can persist in vivo [27]. The low MHC II level on Dex-MΦs may allow the APCs to cap the cumulative strength of Ag stimulation to a low level regardless of the Ag dose, thereby favoring the generation of Treg. We should be able to address this possibility by manipulating the MHC II level on the CD11cloCD40lo macrophages independently of Dex.

Lastly, this study also reveals unexpectedly that clodronate lipososme-sensitive macrophages, which include the Dex-MΦs, are not a significant source of serum IL-12 upon recall Ag stimulation in vivo. Although it is unclear whether these cells account for all macrophages, the observation indicates that at least a significant portion of the macrophages are poorly immunogenic when exposed to recall Ags without an immunogenic adjuvant. Given this property, do the macrophages play a regulatory role in T cell recall responses? Future studies are needed to answer this question.

Materials and methods

Mice and reagents

Balb/c, Foxp3-eGFP (on a Balb/c background), and C57BL/6 mice were from the Jackson Laboratory and used in accordance with the institutional guidelines for animal care. All Abs were from Biolegend; Dex, mifepristone, and hen OVA (grade VII), from Sigma-Aldrich; incomplete Freund’s adjuvant and BrdU, from Thermo-Fisher Scientific; the OVA323–339 peptide (ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR), from AnaSpec; reagents for MACS purification of CD4+ T cells and CD11c+ cells, from Miltenyi Biotec; and the reactive dye eFluor 670, from eBioscience. Clodronate liposomes were a gift of Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany).

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen or pooled lymph nodes (axillary, brachial, inguinal, and popliteal) by gently homogenizing the tissues on ice followed by filtration (0.4 μm). Blood leukocytes were collected by centrifugation following lysis of red cells with ACK. Flow cytometry was performed with a FACSCalibur and the Cellquest pro software (BD Biosciences). CD11c+ cells were analyzed either in bulk cells or after being enriched by MACS; in the former case, CD3/CD19 co-staining was used to gate out a large portion of T and B cells. Intracellular immunostaining of IL-10 was described before [5]. Cells were, without in vitro restimulation, immunostained with anti-CD11c and anti-F4/80 mAbs, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Tween-20, and intracellular stained with anti-IL10 mAb.

Induction of DTH

OVA-specific DTH was induced as previously described [5]. Mice showing DTH were deemed OVA-sensitized and used for experiments.

Co-adoptive transfer of Ag-primed APCs and T cells

OVA-sensitized Balb/c mice were injected with OVA323–339 (50 μg, i.v.) either alone or in combination with Dex (4.5mg/kg, s.c.). At 16 h, Ag-primed MΦs or Ag-primed Dex-MΦs were isolated from the spleen as CD11cloF4/80hi cells by flow sorting and used as donor APCs. Donor CD4+ T cells were isolated from OVA-sensitized Balb/c Foxp3-eGFP mice by MACS (negative selection) and labeled with 5 μM eFlour 670, as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The mixture of the donor APCs (3 × 104) and donor T cells (2 × 106) was injected (s.c.) into a footpad of naïve Balb/c mice (day 0). At 24 h, DTH was measured by swelling of the footpad, as described [5]. On day 4, the draining LN (popliteal) was analyzed by flow cytometry. Proliferation of T cells was determined by dilution of intracellular eFlour 670.

In vivo BrdU incorporation

Mice were injected (i.p.) twice with BrdU (1 and 0.5 mg/mouse in a 4-h interval). Twelve hours later, CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleen by MACS and immunostained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD44 mAbs. The cells were fixed (4% paraformaldehyde), permeabilized (0.5% Tween-20), digested with DNAse I (0.02 kU/106 cells), intracellularly immunostained with anti-BrdU mAb, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Suppressed immunization

Mice were injected (s.c.) with 90 μg Dex (4.5 mg/kg) on day 1 and 45 μg Dex on days 3, 5, and 7. OVA323–339 was injected (50 μg/mouse, i.v.) on days 3 and 5. This regimen was given twice in a 2-wk interval. To deplete macrophages during suppressed immunization, clodronate liposomes (0.5 mg clodronate/ml) [18] or control liposomes were injected (100 μl/mouse, i.v.) on day 2. Depletion of macrophages was confirmed by flow cytometry at 24 h.

Statistic analysis

Unpaired two-sided Student’s t test was used for pairwise comparison, as described [5].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank John Javaherian of the University of Illinois for his assistance with the animal studies. We also thank Drs. Xunrong Luo and Stephen D. Miller of the Northwestern University for their critiques of this work. This work was supported in part by grant R21HL106340 from the National Institutes of Health and grants from the Swedish American Health System (to G.Z. and A.C.), and grant from American Diabetes Association (to G.Z.)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity. 2010;33:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Oppenheim JJ, Winkler-Pickett RT, Ortaldo JR, Howard OM. Glucocorticoid amplifies IL-2-dependent expansion of functional FoxP3(+)CD4(+)CD25(+) T regulatory cells in vivo and enhances their capacity to suppress EAE. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2139–2149. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X, Murakami T, Oppenheim JJ, Howard OM. Differential response of murine CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells to dexamethasone-induced cell death. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:859–869. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hackstein H, Thomson AW. Dendritic cells: emerging pharmacological targets of immunosuppressive drugs. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:24–34. doi: 10.1038/nri1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang Y, Xu L, Wang B, Chen A, Zheng G. Cutting edge: immunosuppressant as adjuvant for tolerogenic immunization. J Immunol. 2008;180:5172–5176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauci AS, Dale DC, Balow JE. Glucocorticosteroid therapy: mechanisms of action and clinical considerations. Ann Intern Med. 1976;84:304–315. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-84-3-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe M, Colvin BL, Thomson AW. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: in vivo regulators of alloimmune reactivity? Transplant Proc. 2005;37:4119–4121. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.09.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruedl C, Koebel P, Bachmann M, Hess M, Karjalainen K. Anatomical origin of dendritic cells determines their life span in peripheral lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2000;165:4910–4916. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakano H, Lin KL, Yanagita M, Charbonneau C, Cook DN, Kakiuchi T, Gunn MD. Blood-derived inflammatory dendritic cells in lymph nodes stimulate acute T helper type 1 immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:394–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yona S, Jung S. Monocytes: subsets, origins, fates and functions. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:53–59. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283324f80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor PR, Brown GD, Geldhof AB, Martinez-Pomares L, Gordon S. Pattern recognition receptors and differentiation antigens define murine myeloid cell heterogeneity ex vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2090–2097. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor PR, Reid DM, Heinsbroek SE, Brown GD, Gordon S, Wong SY. Dectin-2 is predominantly myeloid restricted and exhibits unique activation-dependent expression on maturing inflammatory monocytes elicited in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2163–2174. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohyama M, Ise W, Edelson BT, Wilker PR, Hildner K, Mejia C, Frazier WA, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Role for Spi-C in the development of red pulp macrophages and splenic iron homeostasis. Nature. 2009;457:318–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blasius AL, Giurisato E, Cella M, Schreiber RD, Shaw AS, Colonna M. Bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 is a specific marker of type I IFN-producing cells in the naive mouse, but a promiscuous cell surface antigen following IFN stimulation. J Immunol. 2006;177:3260–3265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato K, Fujita S. Dendritic cells: nature and classification. Allergol Int. 2007;56:183–191. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.R-06-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villadangos JA, Heath WR. Life cycle, migration and antigen presenting functions of spleen and lymph node dendritic cells: limitations of the Langerhans cells paradigm. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutella S, Danese S, Leone G. Tolerogenic dendritic cells: cytokine modulation comes of age. Blood. 2006;108:1435–1440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-006403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Rooijen N, Hendrikx E. Liposomes for specific depletion of macrophages from organs and tissues. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;605:189–203. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-360-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chensue SW, Terebuh PD, Remick DG, Scales WE, Kunkel SL. In vivo biologic and immunohistochemical analysis of interleukin-1 alpha, beta and tumor necrosis factor during experimental endotoxemia. Kinetics, Kupffer cell expression, and glucocorticoid effects. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:395–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zen M, Canova M, Campana C, Bettio S, Nalotto L, Rampudda M, Ramonda R, Iaccarino L, Doria A. The kaleidoscope of glucorticoid effects on immune system. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinds TD, Jr, Ramakrishnan S, Cash HA, Stechschulte LA, Heinrich G, Najjar SM, Sanchez ER. Discovery of glucocorticoid receptor-beta in mice with a role in metabolism. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1715–1727. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabat R, Grutz G, Warszawska K, Kirsch S, Witte E, Wolk K, Geginat J. Biology of interleukin-10. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haxhinasto S, Mathis D, Benoist C. The AKT-mTOR axis regulates de novo differentiation of CD4+Foxp3+ cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:565–574. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kretschmer K, Apostolou I, Hawiger D, Khazaie K, Nussenzweig MC, von Boehmer H. Inducing and expanding regulatory T cell populations by foreign antigen. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/ni1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauer S, Bruno L, Hertweck A, Finlay D, Leleu M, Spivakov M, Knight ZA, Cobb BS, Cantrell D, O’Connor E, Shokat KM, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M. T cell receptor signaling controls Foxp3 expression via PI3K, Akt, and mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800928105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner MS, Kane LP, Morel PA. Dominant role of antigen dose in CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell induction and expansion. J Immunol. 2009;183:4895–4903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.