Abstract

Defective expression or function of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) underlies the hypersusceptibility of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients to chronic airway infections, particularly with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. CFTR is involved in the specific recognition of P. aeruginosa, thereby contributing to effective innate immunity and proper hydration of the airway surface layer (ASL). In CF, the airway epithelium fails to initiate an appropriate innate immune response, allowing the microbe to bind to mucus plugs that are then not properly cleared because of the dehydrated ASL. Recent studies have identified numerous CFTR-dependent factors that are recruited to the epithelial plasma membrane in response to infection and that are needed for bacterial clearance, a process that is defective in CF patients hypersusceptible to infection with this organism.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is unique among human genetic disorders in that mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, which encodes a protein whose primary function described to date has been to regulate conductance of ions in and out of cells and intracellular vacuoles, lead to hypersusceptibility to chronic lung infection. Human diseases wherein individuals homozygous for mutant genes are predisposed to infections serve as a firm foundation for understanding the molecular, cellular, physiologic and immunologic aspects of normal and compromised resistance to infection. CF is not just a prime example of how we can learn about normal and pathologic states; it could, in fact, be the only known human genetically determined disease wherein infection with a single pathogen – Pseudomonas aeruginosa – drives the vast majority of morbidity, clinical deterioration and ultimately life-shortening mortality encountered in this disease. In humans with significant compromises to their immune system, such as advanced AIDS, we would normally expect to see a plethora of pathogens take advantage of this debilitated state, but this is not the case in CF.

CF is characterized by the emergence and persistence of (and, ultimately, the inability to clear) chronic infection with a variant of P. aeruginosa (mucoid P. aeruginosa) that over-produces a surface polysaccharide known as alginate. The organism undergoes other significant genetic adaptations and selections within the CF lung, and it is the emergence of mucoid P. aeruginosa that is the primary determinant of the clinical course of this disease [1,2]. In those individuals with either an uncommon but fortuitous protective immune response to specific P. aeruginosa antigens [3,4] or the ∼10–15% of patients with at least one ’mild’ allele encoding a mutant CFTR that still retains wild-type (WT) resistance to P. aeruginosa infection [3], the clinical course of CF lung disease is much more benign. Clearly the lack of WT-CFTR function and the high rate of P. aeruginosa infection in CF patients indicates a specific link between defective CFTR and hypersusceptibility to infection with this pathogen.

Histopathologic basis for defining relevant interactions between P. aeruginosa and the CF airway epithelium

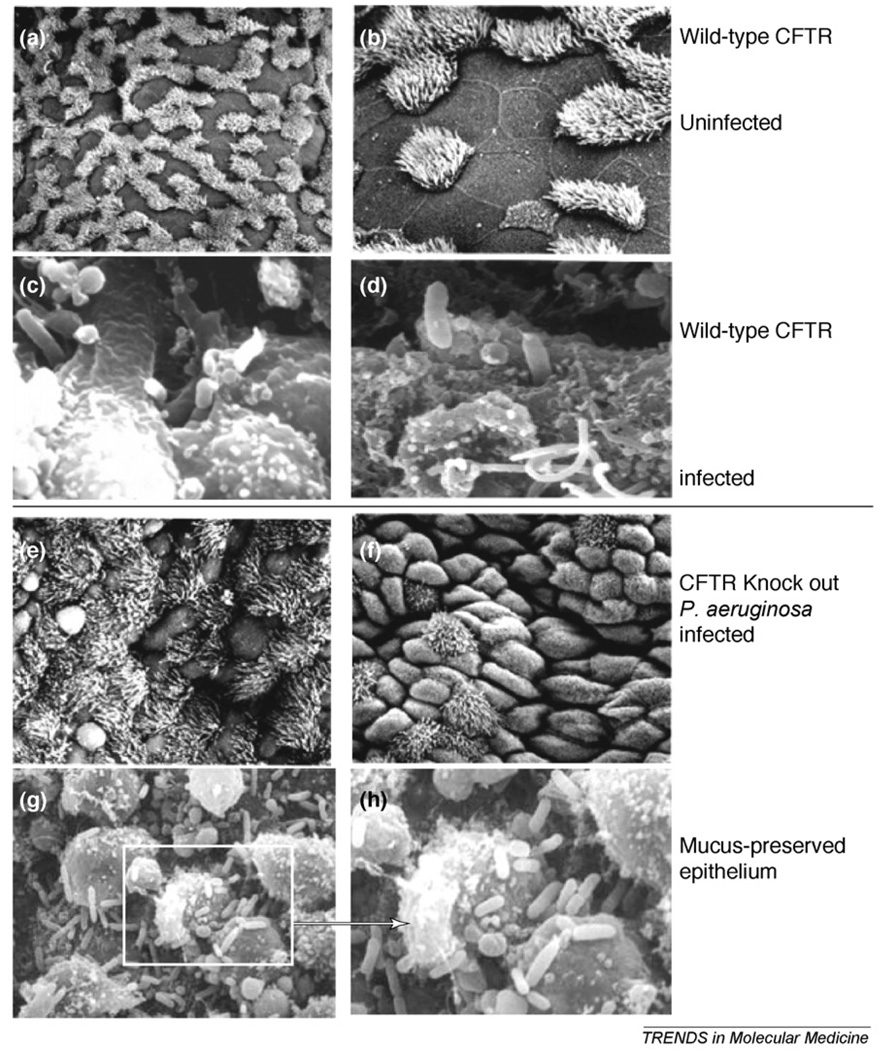

Although CF is a multisystem disease characterized by GI and nutritional abnormalities, salt loss syndromes and male urogenital abnormalities, the major clinical problem for CF patients is chronic sinopulmonary disease. Therefore, relying on observations made from the pathologic and histopathologic analysis of affected tissues provides substantial insight into the pathogenesis of this disease. Observations of the CF airway epithelium in tissues taken at autopsy or transplant [5–7] and observations made during experimental infection of WT and transgenic CF mice [8] clearly show that P. aeruginosa rarely binds to the airway epithelial cells in the CF lung but does so vigorously in mice expressing WT-CFTR (Figure 1a–d). The bacteria in the CF mouse are not observed interacting with the epithelium (Figure 1e,f) but rather found primarily within the mucus (Figure 1g,h), as in CF patients [7], where P. aeruginosa is primarily visualized to be trapped in mucus plugs that predominantly form in the airways [7]. In acutely-infected WT mice, P. aeruginosa cells trapped in the mucus are also readily seen (not shown), but these organisms are effectively cleared from the lung [8]. Thus, hypothesis evaluating the responses of the airway epithelium to this pathogen must be consistent with these clinical and experimental observations. In this regard, experimental results that do not show a much higher degree of interaction of P. aeruginosa with cells expressing WT-CFTR in comparison to those expressing only mutant CFTR are inconsistent with the processes that occur within the CF lung. To wit, results showing that WT-CFTR is a receptor for P. aeruginosa that mediates effective innate immunity and that this receptor is not functional in CF [9,10] are the ones most consistent with clinical and experimental observations. One curious additional observation about this interaction has also been reported: the mucoid strains of P. aeruginosa responsible for chronic infection lose the bacterial ligand for CFTR [8,11,12], indicating that the P. aeruginosa–CFTR direct interaction is likely to be primarily of relevance to the early stages of infection, whereas in the later stages of infection other properties of the bacterium and the CF host conspire to allow for maintenance of the chronic infectious state.

Figure 1.

Visualization of P. aeruginosa in the tracheal epithelium 4 h after infection with an LPS-smooth, non-mucoid isolate. In mice with WT-CFTR (a–d), the uninfected epithelium shows mixtures of ciliated and non-ciliated cells in a firm layer, whereas in the P. aeruginosa-infected epithelium the organisms are seen entering the tracheal epithelial cells, usually with one of the polar ends being taken into an obvious membrane invagination. In transgenic CFTR-knockout-mice (e–h), the infected tracheal epithelial surface looks only modestly disrupted, with no bacterial cells observed bound or entering the epithelial cells. When sections are treated to preserve the mucus (g,h), the bacteria seen in the CF epithelium are primarily entrapped within or on the mucus material.

However, there are clearly investigators who hypothesize that the major role of the airway epithelium in susceptibility to P. aeruginosa lung infection is through defects in ion transport, leading to dehydrated airway surface layer (ASL) and thickened mucus that cannot be cleared by the ciliary escalator. This is a necessary but not sufficient component of the pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa in CF that is well documented and supported by the work of Boucher and colleagues [13]. But this abnormal physiology does not provide an explanation for why P. aeruginosa is so clearly the predominant pathogen in CF, as other pathogens could probably take advantage of this niche to cause lung infection. Indeed, in human genetic diseases such as immotile ciliary disorders, or the subset of these patients with Kartagener’s syndrome, the loss of ciliary clearance of mucus clearly predisposes to frequent bronchiectasis, sinusitis and otitis but without the predominance of P. aeruginosa as an etiologic agent of infection, as is seen in CF [14]. In these patients, mucoid P. aeruginosa infection, where it occurs in ∼15% of affected individuals, primarily emerges after 30 years of age [14], whereas among CF patients, over 80% are infected with this organism by late adolescence. Furthermore, in the disease diffuse panbronchiolitis, found commonly in Japanese patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and thus impaired interactions of the airway epithelium with P. aeruginosa, mucoid P. aeruginosa infection is common, although CFTR function is intact [15]. Thus, when one views the pathogenesis of CF lung disease as involving multiple lung abnormalities derived from loss of functional CFTR and thickened mucus with the proposal that CFTR is a receptor for P. aeruginosa mediating critical aspects of innate immunity, a picture emerges that explains how different physiologic abnormalities resulting from loss of proper CFTR function all contribute to the pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa in the CF lung.

Pathogenesis of lung infection in CF

Overview of pathogens and current understanding of their contribution to disease

An established dogma is that the lungs of CF patients are usually colonized by pathogens in an age-dependent sequence. Traditionally, the organisms most frequently found during the early colonization of CF airways are Staphylococcus aureus and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, followed later by P. aeruginosa, with organisms of the Burkholderia cenocepacia complex at times causing a rapid clinical decline in a subset of usually older patients. Other pathogens that can also be found in oropharyngeal cultures from CF patients who generally have been chronically infected with P. aeruginosa for a while are Stenotro-phomonas maltophilia, Achromobacter xylosoxidans, Mycobacterium spp., Aspergillus fumigatus, Pandoraea apista, Ralstonia spp., Inquilinus limosus and a variety of other uncommon organisms. These microbes have an uncertain effect on the overall pathology and clinical status of the respiratory tract of CF patients. However, recent clinical studies indicate that the early pathogens, S. aureus and H. influenzae, are less common now than they were previously and might not currently be contributing significantly to CF lung disease (although they might have in the past), and fortunately, infections with most of the pathogens other than P. aeruginosa are rare.

Early pathogens: Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae

The most common organisms isolated from CF airways during infancy and early childhood are S. aureus and H. influenzae. It has been proposed that they might damage the epithelial surfaces, leading to increased attachment of P. aeruginosa [16]. However, their role in the pathogenesis of lung disease continues to be a topic of discussion, as well as whether treating these infections has clinical benefit. Different clinical trials have demonstrated that continuous anti-staphylococcal antibiotic treatment lowers the rates of S. aureus positive cultures but increases the rate of P. aeruginosa acquisition and produces no discernable clinical benefits [17,18]. Therefore, S. aureus prophylaxis is no longer routinely recommended, and anti-staphylococcal antibiotics should probably only be used intermittently for respiratory symptoms that are likely to be exacerbated by S. aureus, based on clinical judgment. A recent finding, which generated some controversy [19], indicated that children with CF on lung transplant waiting lists from 1992 to 2002 who did not receive a transplant and harbored S. aureus had better survival rates before transplant compared to non-transplant CF patients without S. aureus infection. Interestingly, post-transplant, S. aureus infection decreased survival, probably because of immunosuppression. Additionally, several recent papers have reported that S. aureus can routinely be obtained from throat cultures of healthy individuals at levels equal to or greater than those found by culturing the anterior nares, thought to be a major reservoir of this organism in most humans [20], suggesting that a positive throat culture for S. aureus from a CF patient might reflect nothing more than what also occurs with this organism in otherwise healthy individuals who are simply S. aureus carriers.

H. influenzae has a pathogenic role in patients with non-CF bronchiectasis, but there are no data clearly associating this pathogen with clinical deterioration in CF patients.

P. aeruginosa – the main problem

It is generally accepted that P. aeruginosa is the most clinically important pathogen in CF lung disease. Its prevalence in CF respiratory tract cultures goes from 10 to 30% at ages 0–5 years to 80% at ages ≥ 18 years [17]. Early acquisition of this pathogen is a predictor for a worse prognosis [2]. The presence of P. aeruginosa in the respiratory tract and the inflammatory response it elicits are associated with an increase in the rate of deterioration in lung function, and these factors are the leading causes of most of the morbidity and ultimate mortality in CF [21]. Chronic P. aeruginosa infection increases the risk of death 2.6 times [1].

Early P. aeruginosa isolates are usually non-mucoid, motile and highly susceptible to antibiotics, suggesting they are usually acquired from the environment [17,22], although recent outbreaks of so-called ’epidemic’ strains being passed from patient to patient suggest some isolates might acquire an enhanced transmissibility, although the basis for this is unknown [23]. An interesting observation made in Danish CF patients suggests that two highly transmissible clones can be isolated from many different patients within their Copenhagen center, suggesting an ability of evolutionarily successful P. aeruginosa variants to supplant environmentally acquired strains and be a significant cause of lung function decline and disease progression [22]. However, current findings still indicate that the most profound increases in the rate of lung function decline occur when P. aeruginosa undergoes genotypic changes, leading to a mucoid phenotype characterized by over-production of a surface polysaccharide known as alginate and the loss of the ability to produce lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O side chains [3,24]. Numerous other genetic changes have been identified in mucoid isolates from CF patients [25], indicating that multiple genetic adaptations confer increased resistance to the innate and acquired host immune defenses and to antibiotic therapy [1,16,17]. This makes eradication of mucoid P. aeruginosa from the CF lung practically impossible. Overall, an analysis of the interaction of P. aeruginosa with the airway epithelium in CF needs to consider the different variants of this organism and how its variable phenotypic properties are likely to influence the host responses at a given stage of the clinical disease.

Host factors allowing P. aeruginosa to initiate infection in the airway

CFTR is best-studied as a cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-regulated chloride channel. In CF, the consequent deficiency in chloride transport affects the ionic composition of epithelial cell secretions and biosynthesis of mucous. The alterations in pH, ion concentration and ASL hydration are all potential factors contributing to P. aeruginosa infecting a high proportion of CF patients. Although it has been proposed that there is an elevated salt concentration in CF ASL that inhibits the activities of antibacterial substances, including lysozyme, lactoferrin and β-defensins [26], most studies [13] have not confirmed the early observation. Better established are findings pointing to a high viscosity of the ASL that then hinders the normal beat of the ciliated airway epithelial cells, which in turn compromises mechanical clearance of P. aeruginosa from the airway, allowing for retention of organisms within the airway lumen [7] (Box 1). Although this component of CF lung disease emanating directly from non-functional CFTR is likely to be critical to the overall pathology of chronic lung infection, it does not explain the extremely high propensity for the CF airway to be infected by P. aeruginosa and not by other common respiratory pathogens.

Box 1. Multi-factorial molecular and cellular basis for hypersusceptibility of CF patients to P. aeruginosa .

CFTR is a receptor for non-mucoid, initially-infecting P. aeruginosa, coordinating effective innate immunity at the initial stages of infection.

Dehydrated airway surface liquid in CF decreases mucociliary clearance.

Mucus plugs provide a microaerophilic to anaerobic environment that promotes the emergence of mucoid phenotype.

Adaptive immune response to mucoid P. aeruginosa is ineffective.

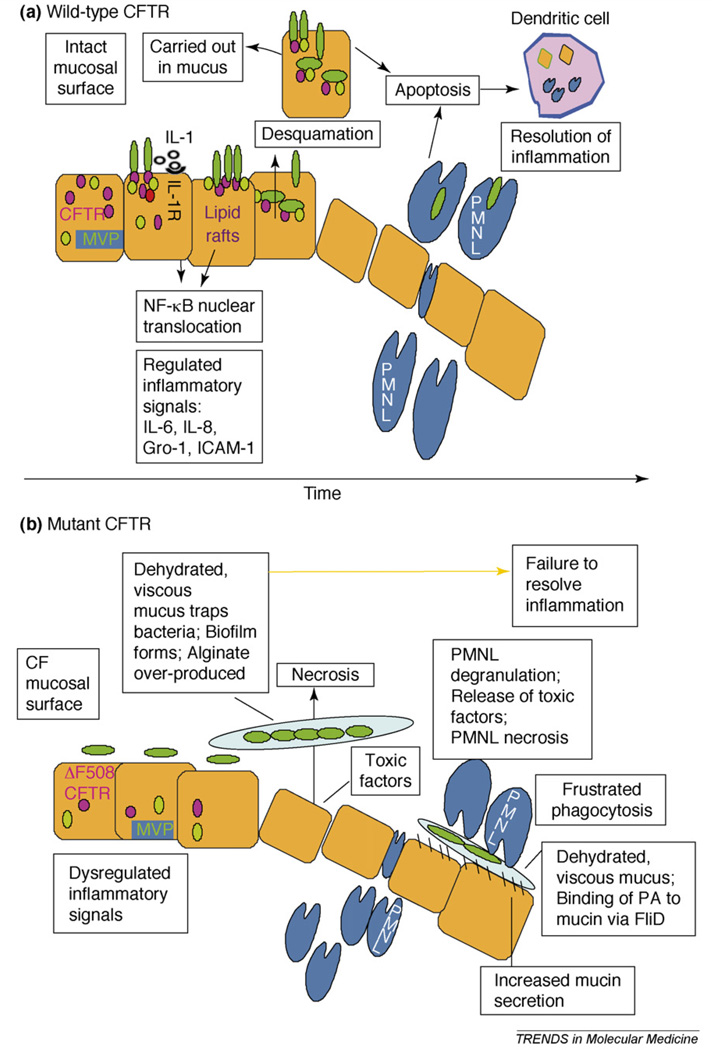

We have proposed that the high incidence of P. aeruginosa infection in the CF lung is due, in part, to the lack of WT-CFTR, which in healthy individuals functions as a receptor for P. aeruginosa and normally initiates a coordinated, rapid and self-limiting inflammatory response that quickly eliminates this pathogen from the respiratory tract and returns the tissue to its baseline state (Figure 2, Box 2). P. aeruginosa recognition by WT-CFTR is due to the specific binding of amino acids 108–117 to the conserved bacterial outer core LPS [11,12,27]. CFTR binding to P. aeruginosa results in release of interleukin-1b from preformed stores in lung epithelial cells within 2–15 min [28], followed by rapid formation (5–15 min) of CFTR-containing lipid rafts in the plasma membrane, with P. aeruginosa cells attached to the CFTR. Subsequently, nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) occurs over the next 10–30 min [12] due both to signals transduced by the interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor and additional, unknown signals dependent on the formation of the lipid rafts. NF-κB nuclear translocation is dependent on the signaling adaptor protein myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) [28]. An additional component of the WT-CFTR-dependent response to P. aeruginosa is endocytosis by the epithelial cells and subsequent clearance of infected epithelial cells by desquamation over the next few hours [11,27]. Over the next 3–12 h, NF-κB-dependent gene transcription and protein secretion ensues that initiates a neutrophil influx into the lung tissue to remove residual surviving bacteria [29]. Finally, inflammation is resolved by the induction of apoptosis to restore tissue homeostasis [30].

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of airway epithelial response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. On an intact mucosal surface (a), some P. aeruginosa cells bind to CFTR, initiating a rapid, regulated inflammatory response to eliminate infecting organisms and restore tissue homeostasis. On a CF mucosal surface (b), failure to produce functional CFTR in the plasma membrane prevents initiation of the proper, desirable and coordinated host inflammatory response and instead elicits dysregulated inflammation, particularly when bacteria become trapped in mucus plugs.

Box 2. Rapid CFTR-dependent host response to P. aeruginosa infection, resulting in effective innate immunity.

Binding of CFTR amino acids 108 –117 to P. aeruginosa LPS outer core.

Release of IL-1 β (2–15 min) and signaling through the IL-1 receptor and adaptor molecule MyD88 (10–20 min).

Formation of CFTR-containing lipid rafts (10–30 min) and recruitment of over 150 new proteins to the rafts, including major vault protein (MVP).

NF- κB nuclear translocation (10–30 min) followed by transcription of NF- κB-dependent genes and production of proteins (IL-6, IL-8, CXC ligand 1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1).

Recruitment of PMNLs to infected tissue.

Induction of apoptosis and resolution of infection and appropriate inflammation.

The lack of functional CFTR prevents these responses from being elicited in a rapid manner in the CF airway epithelium infected with P. aeruginosa [31,32]. The diminished or non-existent binding of P. aeruginosa to the CF epithelium leads to a reduced initial clearance, allowing the organisms sufficient time to take advantage of the dehydrated ASL and remain within the airway lumen by binding to mucins via the bacterial FliD protein [33]. Subsequently, the microbial cells survive and grow within a hypoxic environment [7,34], wherein increased production of alginate occurs [7,35], further serving to protect the microbe from host defenses. In transgenic CFTR-knockout mice, NF- κB nuclear translocation occurs much later in the airway epithelial cells [28], probably contributing more to the harmful inflammation that ensues in this environment instead of the protective inflammation that occurs when functional CFTR is present. Overall, this scenario wherein WT-CFTR binding of P. aeruginosa leads to protection and failure of this interaction in CF leads to infection is supported by data obtained in numerous in vitro and, importantly, in υivo, studies demonstrating CFTR-dependent responses to P. aeruginosa in a variety of lung epithelial cell lines and in transgenic animals [8– 12,27–29,31,36]. Thus, it seems that CFTR facilitates bacterial clearance and modulates innate immunity towards P. aeruginosa in lung epithelial cells by being the linchpin needed for coordinating multiple host responses involved in resisting infection and maintaining tissue homeostasis in the long run.

A recent approach to determine the molecular components that govern the CFTR-dependent epithelial cell responses to P. aeruginosa has utilized an analysis of host proteins recruited to lipid rafts in human airway epithelial cells within 15 min of infection with P. aeruginosa [36]. About 150 proteins were identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry analysis that were present exclusively in the P. aeruginosa-induced rafts. Among these proteins, we identified the major vault protein (MVP, also referred to as the lung resistance protein). Multiple (96) copies of MVP molecules assemble to form barrel-like structures called vaults that contain two additional proteins, vault poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (vPARP) and telomerase-associated protein 1 (TEP1), along with untranslated vault RNA sequences (vRNAs). The function of these ribonucleoprotein complexes had not been previously recognized. When the protein levels of MVP were reduced in epithelial cells, the endocytosis of P. aeruginosa was markedly diminished. Notably, mice deficient for MVP demonstrated enhanced sensitivity to P. aeruginosa lung infection, which presented with elevated bacterial levels in the lungs of the knockout animals. However, MVP deficiency failed to impact other aspects of the CFTR-mediated inflammatory responses to P. aeru-ginosa in the lung epithelium, suggesting that the additional factors identified by the proteomic analysis are likely to be involved in the full breadth of airway epithelial responses to P. aeruginosa leading to effective bacterial clearance.

Other components of the innate immune system thought to be important in the P. aeruginosa–epithelial cell interaction are the toll-like receptors (TLRs) that respond to conserved bacterial factors such as peptidoglycan (TLR2) or LPS (TLR4) and facilitate bacterial recognition and the subsequent inflammatory responses. Although more than 10 TLRs have been identified, not all of them participate in the epithelial response to inhaled P. aeruginosa. The most crucial so far are TLR2, TLR4, TLR5 (which recognizes bacterial flagellin) and TLR9 (which recognizes DNA with a high CpG content, such as that made by P. aeruginosa) [37]. In υitro studies of airway epithelial cells indicate that some of the TLRs mediate cellular responses to P. aeruginosa. TLR2 reportedly forms complexes with asialo-gangliotetraosyl ceramide (asialo GM1), initiating proinflammatory responses after infection with P. aeruginosa in υitro [38]. However, to emphasize the importance of finding in υiυo correlates of in υitro findings, no single TLR-deficiency in transgenic mice has been found to seriously compromise the mammalian response to P. aeruginosa lung infection. Neither single deficiencies in TLR2 or TLR4 nor a combination deficiency of both of these molecules seems to have much impact on controlling P. aeruginosa lung infection in mice [39]. Similarly, mice singly lacking TLR5 were not more susceptible to P. aeruginosa infection [37], but alterations in cytokine responses and defects in bacterial clearance from lack of two TLRs in multi-transgenic animals have been observed. Thus, a combination of deficiency of TLR4 and TLR5 resulted in a modest enhancement of lethality when an otherwise non-lethal dose of P. aeruginosa was given, and a shorter time to death was achieved when a dose lethal for all of the WT control mice was used [37]. However, another group [40] found TLR5-deficient mice had a slower response and delayed time to death followingP. aeruginosa lung infection, and the absence of the bacterial ligand for TLR5, flagella, did not itself impact the virulence of P. aeruginosa in the lungs of adult mice. This might have been due to the fact that TLR5 recognizes the monomeric flagellin subunit and not the intact, highly polymerized bacterial flagella, and it appears that WT P. aeruginosa does not produce much, if any, monomeric flagellin in culture or during infection [40].

Much of the airway epithelial cell response to infection depends on signaling via the MyD88 adaptor protein, leading to activation of NF- κB and production of various cytokines. In contrast to the findings with TLR-deficient animals, MyD88-deficient mice show little neutrophil recruitment in the lungs after P. aeruginosa infection, reduced ability to produce macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP2), tumor necrosis factor- α (TNF- α) and IL-1β and have elevated bacterial counts in the lungs after infection [38,41]. These findings suggest an essential role for the MyD88-dependent cascade in the host defense against P. aeruginosa, which appears to be induced by rapid IL-1 release from epithelial cells with WT-, but not mutant-, CFTR. Signaling through the IL-1 receptor leads to NF-κB nuclear translocation within 10–20 min of infection [28]. Consistent with these findings, the lungs of IL-1 receptor-deficient mice can be chronically infected with P. aeruginosa after oral exposure via drinking water [28], in the same way that chronic infections can be established in transgenic CF mice [42]. Overall, the key host responses to P. aeruginosa mediating high-level resistance to infection involves CFTR-dependent recognition and response to this pathogen, a modulated host inflammatory response that includes limited neutrophil recruitment to the lungs dependent on signaling involving MyD88, contributions from TLRs that are not dependent on a single TLR due to redundancy in this host response system and resolution of this sub-clinical, beneficial inflammatory response by proper apoptosis of involved cells. Compromises to these responses, which occur readily in cells and lung tissues lacking functional CFTR, enhance the susceptibility to P. aeruginosa infection.

An additional question related to the airway epithelial cell response to bacterial agonists for TLRs is how do these cells respond to microbial factors that are actually produced during infection, which are unlikely to be adequately represented by the purified molecules so often used in experimental studies? A recent report showed that TLR-dependent responses in dendritic cells do not occur as a result of direct activation of the TLRs on the cell surface but rather occur inside phagosomes after bacterial uptake [43]. It seems likely that a similar situation must occur in order for airway epithelial cells to respond to TLR agonists made by P. aeruginosa. Therefore, CFTR-dependent internalization of P. aeruginosa into epithelial cell endosomes could be a key factor in activating airway epithelial cells via TLR signaling in WT cells, wherein acidification of endosomes releases TLR agonists from the bacterial surface to mediate proper host responses. For example, brief exposure of polymeric flagella to low pH releases flagellin monomers that are the agonists for TLR5 [44]. These interactions would not occur in CF cells unable to internalize P. aeruginosa in a CFTR-dependent manner.

P. aeruginosa virulence factors impacting the CF lung response

Initiation of infection

The reduced binding of P. aeruginosa to respiratory epithelial cells in CF patients because of lack of expression of CFTR results in delayed host clearance, allowing the microbial cells sufficient time to bind to mucins in the mucus layer overlying the dehydrated ASL. Mucin binding is mediated by the FliD [33] protein at the tip of the bacterial flagella. FliD can also be detected on the bacterial surface in the absence of expression of intact flagella [33]. Interestingly, inflammatory respiratory mucus quickly initiates loss of flagella protein synthesis by inducing a shut-off of synthesis of the FliC protein that forms the flagellin monomer [45]; however, normal mucus does not do this [46]. In inflamed mucus, free neutrophil elastase degrades the flagellar hook protein FlgE, which prevents export of the FliC protein and formation of flagella [46]. Alginate synthesis is also induced quickly in the infected lung [35], and P. aeruginosa mutants unable to produce alginate cannot establish chronic infections in transgenic CF mice [42]. It is not known exactly when the organisms switch to the mucoid, alginate-overexpressing phenotype in CF patients. One recent study suggested this switch make take as long as 10 years, on average, before mucoid P. aeruginosa is routinely detected by microbiologic cultures [1]. Although many studies, conducted almost exclusively in υitro using cultured cells, have proposed that other P. aeruginosa surface factors such as pili, lectins and other adhesins can influence epithelial cells and initiate such responses as activation of the NF-κB innate immune response pathway associated with subsequent proinflammatory gene expression [40], this does not appear too relevant to CF as P. aeruginosa is never observed to bind to the CF epithelium in υiυo [5–7]. Furthermore, this organism only minimally binds to the respiratory epithelium of transgenic CF mice within hours of experimental infection [8]. Because it is not known what initially occurs in the CF lung after infection with P. aeruginosa, the available data best support a conclusion that whatever CFTR-independent interactions are occurring between P. aeruginosa and the CF airway epithelium, they do not contribute to host clearance and resistance to infection but might be important in the inappropriate inflammatory responses that do emerge within the CF lung and are significant components of pathology during chronic infection.

Establishment of chronic infection

Recent studies have indicated that significant genetic changes occur in chronically infecting P. aeruginosa strains recovered from CF patients, whereas non-mucoid, typically LPS-smooth P. aeruginosa strains isolated during early colonization tend to have an intact chromosome typical of that from sequenced strains such as PAO1 and PA14 [25]. During this early phase, little clinically significant decline in lung function is seen [1,47]. It is the emergence of the mucoid phenotype that is clearly associated with a significantly increased rate in the decline in CF lung function [3,24]. Emergence of the mucoid phenotype is associated with genetic mutations in the algU-mucABCD gene cluster [48–50]. The AlgU (also called AlgT) protein is an alternative sigma factor that is needed for maximal transcription of the genes within the alginate (alg) biosynthetic cluster and binds to the promoter for the first gene, algD. However, in non-mucoid P. aeruginosa strains, the AlgU protein is bound to the MucA protein and anchored to the inner membrane, and thus sequestered from the algD promoter. When mutations arise in the mucA gene leading to loss of intact protein production, the AlgU protein is made available to activate transcription of the alg locus and enhance alginate production. Although reports indicate that there is a common mutation or hot spot in the mucA gene that leads to early termination of translation, a mutation that was found in >84% of clinical mucoid isolates in two studies [48,50], analysis of isolates in Australia showed that a lower percentage (44%) of mucoid strains had this genetic change [51]. Other genetic regulators and P. aeruginosa proteins have also been reported to not only affect alginate production but also other potential virulence factors in a coordinated fashion. However, over-production of alginate remains the hallmark of chronic infection and lung function decline in CF and is a necessary bacterial virulence factor in the pathogenesis of this disease. Overproduction of alginate also reduces P. aeruginosa interactions with the airway epithelium [11], as is seen in lungs of CF patients [5–7].

P. aeruginosa strains that initiate infections in CF can produce a huge arsenal of metabolic and virulence factors [16], can use the nutrients in the lung to promote growth [52] and can synthesize many toxic factors, such as pyocyanin, a type III secretion system, a variety of proteases, lipases and phospholipases, rhamnolipids and other potentially toxic factors [16,21,53]. Another key change in the organism associated with virulence in the CF lung is the loss of synthesis of the LPSO side chain [54] combined with the synthesis of the lipid A component as an isoform more likely to promote inflammation [55]. The loss of the O side chain is thought to allow the organism to avoid host adaptive immune responses. One factor often overlooked in the analysis of P. aeruginosa virulence in the CF lung is that these patients are quite immunocompetent and make potent immune responses to many cell surface and secreted virulence factors [56,57], usually leading to inactivation of their toxicity or virulence-promoting activity. Of note, increased antibody responses to P. aeruginosa in CF patients are associated with a worse clinical status, probably resulting from the inflammatory damage ensuing from the binding of antibodies and/or complement to the bacterial antigens. An interesting recent finding [58] is that both mucoid and non-mucoid cells in the lungs of CF patients are actively growing, with doubling times of 100– 200 min, suggesting that the immune response is actually doing a very credible job of controlling infection and limiting bacterial spread effectively enough to make CF lung disease a chronic, slowly progressing infection as opposed to a rapidly spreading, more acute and potentially more rapid fatal infection.

A major advance in our understanding of expression of P. aeruginosa virulence factors came from a study by Smith et al. [25], who analyzed the genetic adaptations made by P. aeruginosa during chronic infection. A key finding was that many of the virulence factors thought to be needed to initiate infection are selected against during chronic infection. Notably, mutations in the lasR gene involved in quorum sensing, a bacterial method of cell-to-cell communication that is mediated by secretion of small molecules when the bacterial cells achieve high densities and that is needed for maximal formation of biofilms, were commonly found, suggesting this system might not be a major factor in the infected CF lung. However, a recent report [59] suggests that lasR mutants might be ‘social cheaters’ taking advantage of quorum sensing molecules made by a minority of strains within a genetically variant population, such as occurs in the CF lung, to maintain quorum-sensing-dependent virulence traits. Another common mutational event in chronically infecting P. aeruginosa strains occurs in negative regulators of multidrug efflux pumps such as mexZ, leading to the enhanced production of the pumps and the associated increase in antibiotic resistance that usually occurs during the course of CF lung disease [25], probably due to selection during antibiotic therapy.

Some aspects of this high degree of genetic change in P. aeruginosa might be facilitated by the frequent emergence of mutator variants in the CF lung due to mutations in the methyl-directed mismatch repair (MMR) system, with mutations in the mutS gene frequently observed [60]. These changes are often associated with increased antibiotic resistance. More recent studies are also revealing additional factors impacting the virulence of P. aeruginosa in the CF lung. Ventre et al. [61] have shown that regulation of virulence factors is partly achieved by the reciprocal action of two sensor kinases, RetS and LadS, that regulate the transcription of a small regulatory RNA, RsmZ, which itself is an antagonist of the translational repressor RsmA. Overall, it appears that many P. aeruginosa isolates from chronic CF lung infection are non-cytotoxic and non-motile, express low levels of extracellular products, lack a functional type III secretion system, have increased antibiotic resistance but decreased individual quorum sensing activity, display LPS modifications, grow as a microbial mass (biofilm?) with bacterial cells embedded in both host and microbial factors and overexpress alginate. Clearly, at many levels there is tremendous complexity in the genetic changes, microevolutionary forces, impact of host immune responses and changes in the CF lung environment that have led to a shift in thinking toward the idea that chronic CF lung infection is caused by a diverse population of infectious organisms with varying individual potentials to produce virulence factors. Several CF centers have found highly transmissible clones in many patients [22,23], but it is currently not known if these isolates undergo further genetic changes and modifications as chronic infection progresses. Presently, we can conclude that population dynamics of a pool of genetically variant isolates, as opposed to the properties of individual isolates, dictate the ability of P. aeruginosa to chronically persist in the CF lung [25].

Intervention strategies for enhancing resistance to P. aeruginosa infection: current treatments and new approaches

Because mucoid P. aeruginosa continues to be the most worrisome pathogen for those with CF, great efforts are underway to further characterize and develop new and improved strategies to prevent chronic airway infections caused by this organism [1,2] or to deal with the consequences of chronic infection and inflammation. Multiple approaches are being pursued, targeting both the pathogen and the host. The most effective methods prevent or limit infection or the consequences of infection, whereas the more experimental and newer approaches attempt to correct the defective airway epithelial response to P. aeruginosa and produce an environment more akin to that of the WT-CFTR-expressing lung (Table 1). As for modern methods of treating established CF lung disease, several recent publications have reviewed the current practices and latest clinical evidence for efficacious treatments [62– 65].

Table 1.

Approved and investigational intervention strategies to overcome the failure of the CF airway epithelium to control P. aeruginosa infectiona

| Strategy | Aim/effectiveness |

|---|---|

| Strategies that target early infection | |

| Infection control, including patient isolation to prevent contact between infected and currently uninfected CF patients | Prevent transmission of P. aeruginosa. Moderately to highly effective, depending on clinic and practitioners [62] |

| Early eradication via antibiotic treatment | Decrease and possibly eliminate P. aeruginosa infection as soon as it appears. Prevent progression to chronic infection with mucoid P. aeruginosa. Highly effective in uncontrolled clinical trials; practiced commonly in many places, notably Europe [17,67,68] |

| Strategies that target development of infection | |

| Immunotherapy | Active vaccination to prevent acquisition of non-mucoid strains or progression of infection due to emergence of the mucoid phenotype. Moderately successful clinical trial of flagella vaccine, failed trail of LPS O antigen-based vaccines, failed trial of hyper-immune IVIgG to alginate [72] |

| Strategies that target established infection | |

| Antibiotic treatment | Standard antibiotic therapies. Reduces bacterial counts and inflammation [65,100]; Inhaled tobramycin or TOBI® (approved). Reduces bacterial counts and inflammation [64]; Macrolide therapy (mechanism unknown, not anti-bacterial, might be anti-inflammatory or inhibitor of bacterial virulence) [79,80]; Other inhaled licensed antibiotics (phase I to III trials ongoing) and newer anti-bacterial molecules under development [94] |

| Strategies that target inflammatory consequences of infection | |

| Variety of drugs of many classes | High dose ibuprofen effective in clinical trials. Six drugs with different mechanisms of action in phase I–II trials [62,94] |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | Low dose methotrexate in phase I triala. Inhaled cyclosporine (inhibits T-cell activation) in phase II triala. Oral glucocorticoids reduce inflammation but long-term use limited due to adverse effectsa. |

| Inhaled β-adrenergic agonists | Produce short-term increase in airflow, no long-term benefit establisheda |

| Strategies that target CFTR expression or function | |

| Gene therapy | Restore functional CFTR. Minimal success to date, phase I trial in U.S. of compacted DNA, major clinical trials ongoing in the UK [81]. |

| Restoration of CFTR expression and/or potentiation of function | Clinical trials ongoing, three drugs in phase I to II studies, others in pre-clinical development [62,94,96]. Limited success to date with use of aminoglycoside drugs to suppress stop mutations [82,83] |

| Strategies that target the consequences of defective CFTR function | |

| Restoration of salt transport | Four drugs in phase II or III trialsa, encouraging results with Denufosol (P2Y2 receptor agonist) from phase II trial [94,95] |

| Mucus treatment | Two established therapies: recombinant human DNase (Pulmozyme®) [18,62,65] and hypertonic saline inhalation [97] |

| Non-CFTR-specific interventions | |

| Nutritional supplements | Yasoo supplement approved; ALTU-135 in phase III triala. Standard of care is to use pancreatic enzymes, nutritional supplements, vitamins and acid reducers. Overall better nutritional status associated with improved lung function [18,62] |

| Airway clearance | Promotes dislodgment of mucus and mucus plugs and removal of infectious and/or inflammatory lung secretions. Clinically effective in preserving lung functiona [18,62] |

For more information, see http://www.cff.org/research/DrugDevelopmentPipeline/.

Early prevention or eradication of P. aeruginosa colonization

Because of increasingly rigorous infection control recommendations by the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and local CF centers, the majority of early isolates in most U.S. centers remain environmental in origin and therefore proactive intervention is critical to prevent acquisition of chronic infection. Similarly, in Denmark, there is a lot of genetic diversity in the P. aeruginosa strains obtained from CF patients who have been documented to have only intermittent colonization or a recently acquired chronic infection, indicative of acquisition from environmental or possibly diverse clinical settings [22]. Therefore, much attention has been directed to early eradication of P. aeruginosa [17]. Although claims from some European centers indicate remarkable success with this approach based on comparisons of treated patients with historical controls [66,67], early eradication has not been subjected to rigorous clinical trials [68]. In addition, there are concerns that increased antibiotic use could exacerbate the development of antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa [1,17,18]. Thus far, even in the best conducted trials [67], which have been said by some to be of questionable methodology [68], conservative conclusions indicate that early intervention delays chronic colonization in the short term but the use of this therapy might not have gone on long enough to determine the impact on long-term morbidity or mortality [68]. However, still others believe that early interventions with rigorous and routine antibiotic treatments have led to a profound decrease in the occurrence of P. aeruginosa lung infection in CF patients [66,67]. Several clinical trials are currently under way to determine whether early antibiotic interventions that help prevent acquisition of P. aeruginosa infection lead to measurable improvements in clinical outcomes for CF patients [17].

Preventing or limiting the development of infection

Another strategy to consider is the use of immunotherapy against P. aeruginosa, focused on either preventing the initial colonization with non-mucoid strains or limiting the infection to these less-pathogenic types [24] while preventing conversion and emergence of the more virulent mucoid phenotype [69]. Although the innate immune response in CF patients is ineffective in clearing P. aeruginosa from the lungs early in the course of infection, it might be possible to use the acquired immune system to provide protective immunity. Antibodies are the most likely major effectors of such immunity, as the role of the cellular immune system involving T lymphocytes is unclear, although animal data have suggested they might be an important factor [70]. Many virulence factors of P. aeruginosa have been targeted for active immunization against this bacterium, and two vaccines reached phase III clinical trial studies [71,72]. One vaccine was composed of 8 different LPS O antigens, each conjugated to the P. aeruginosa toxin A carrier protein, but recently released results did not show any efficacy of this vaccine (http://investors.crucell.-com/C/132631/PR/200607/1064252_5_5.html). Somewhat better success was obtained with a bivalent P. aeruginosa flagella vaccine. In a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III trial, this vaccine was shown to be safe and immunogenic and to reduce the risk of initial infection with P. aeruginosa strains exhibiting flagella subtypes included in the vaccine [72]. However, a second endpoint – acquisition of chronic P. aeruginosa infection – was not met, as the placebo-control group did not develop these infections at a high enough rate to warrant a meaningful comparison. Nonetheless, the successful component of this trial established vaccination as a likely viable option for preventing the acquisition or consequences of early P. aeruginosa infection in CF.

Another approach has been based on interrogating the antibody responses of CF patients with CFTR-alleles normally associated with severe lung disease, wherein a small percentage do not develop P. aeruginosa infection by early adulthood. Although these patients are rare (<5% of the total), it has been shown that a high proportion have naturally acquired an antibody to the alginate antigen that is characterized by the antibody’s ability to mediate complement-dependent opsonic killing of mucoid P. aeruginosa growing in υitro either as planktonic cells [3,4] or in a biofilm [73]. The antibodies made to alginate by most infected CF patients [3,4], and also by most humans who have natural antibodies to alginate [74], do not mediate efficient opsonic killing because of their specificity for antigenic epitopes on alginate that do not result in deposition of the critical complement opsonin, C3bi, onto the bacterial surface [73]. However, although animal studies indicate there are potential means to induce these opsonically-active antibodies by vaccination [75], this has not readily been achieved in large-scale human trials. Thus, an alternative approach is being pursued, involving the passive administration of a recently described fully human monoclonal antibody to alginate that is opsonic and protective in animal studies [76]. Future goals of improved immunotherapy might also involve the induction of mucosal immunity, particularly local immunoglobulin G (IgG) [77], before colonization with P. aeruginosa [77], as well as the use of different and multiple antigens as vaccine components.

Limiting and treating established infection and the inflammatory consequences on infection

Arguably, the major advance in the care and treatment of CF patients over the past 30 to 40 years has been the use of antibiotics to treat infection. Many standard approaches use traditional antibiotics, but as the infection progresses and the treatments select out for resistant strains, antibiotic therapy becomes more challenging. Empiric use of various combinations of differing antibiotics, older dugs such as colistin and experimental combinations based on antibiotic susceptibility testing, which looks for synergy of different combinations of antibiotics, are all being tried [78]. Macrolide antibiotics, such as azithromycin, have shown clinical efficacy in spite of a lack of anti-bacterial activity [79]. These drugs might work by inhibiting virulence-factor production by P. aeruginosa or by having an anti-inflammatory effect [80].

Inflammatory damage to the airways is clearly a component of pathology, and a variety of approaches are being used or are under evaluation to combat this consequence of infection. High dose ibuprofen [18] has shown clinical efficacy in terms of maintaining lung function, but its use is sporadic. Various drugs with a variety of anti-inflammatory actions are in clinical development (Table 1). Immunosuppressive drugs, such as methotrexate and cyclosporine, are also in clinical trials. Oral glucocorticoids have beneficial short-term effects but long-term use is limited because of adverse effects. Inhaled β-adrenergic agonists can improve airflow in short-term studies, particularly among those demonstrating airway hyper-responsiveness, but have not yet shown a long-term benefit.

Restoration of CFTR expression or function

Recent efforts have thus focused on restoring at least some CFTR protein, and function, to apical surfaces of airway epithelial cells, as the hoped-for results from gene therapy replacement of CFTR are still a long way off [81]. The observation that treatment with gentamicin can suppress stop mutations in some CFTR alleles [82] has helped launch an industry dedicated to the identification of molecules that might aid in improving production and function of CFTR. In a study of nine French CF patients with the Y122X CFTR allele, six patients treated with parenteral gentamicin showed detectable CFTR protein and improved respiratory function and sweat chloride values [83]. In another study of 11 CF patients with stop mutations (none of whom had the Y122X allele), no effect of gentamicin on CFTR expression or nasal potential difference was achieved [84]. Thus, there might be mutation site-specific effects of gentamicin on read-through of stop codons in mutant CFTR alleles.

Other approaches include potentiators (molecules that open chloride channels already present on the apical surface of epithelial cells) and correctors (molecules that help circumvent protein trafficking defects) [85]. The appeal of ‘corrector’ molecules is underscored by the vast majority (65–70%) of CF patients harboring at least one ΔF508 CFTR allele, which is a mutation associated with defective protein processing [86]. Achieving 10–35% of normal CFTR activity might aid in the maintenance of an adequate periciliary liquid layer for improved ion transport and promote adequate clearance of this pathogen [87,88]. However, it is not clear how much WT-CFTR is necessary to establish resistance to P. aeruginosa infection. Although in some CF patients there are mutant CFTR alleles that allow production of near normal levels of membrane CFTR, many are defective in chloride channel function and are associated with persistent P. aeruginosa infection. Anecdotal observation of delayed P. aeruginosa colonization in patients with some ‘mild’ mutant CFTR alleles indicate that these alleles might be associated with retention of normal recognition of this pathogen and resultant initiation of effective innate immunity [12,27,30].

Many compounds have demonstrated that improved trafficking of ΔF508 CFTR can be achieved in υitro, but in υiυo studies are limited [89]. Curcumin (a component of the spice tumeric) has been shown to correct mutant CFTR processing in the cell in some studies [90] but not others [91], and results in mouse models of this disease have remained variable [92]. Other molecules in the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase-(SERCA) pump family also show some promise as therapeutic targets to correct defective CFTR function. Butyrate non-specifically improves ΔF508 CFTR protein expression and function but also promotes expression of many other proteins in the cell. This has led to the development of orally bio-available sodium 4-phenylbutyrate, which demonstrated borderline promising results in a pilot study involving patients homozygous for ΔF508 CFTR [93]. However, these improvements were not augmented with dose escalation and led to unacceptable adverse effects [93]. A phase II clinical trial is underway in CF patients harboring the G551D CFTR allele, which produces a poorly functional CFTR protein in the cell membrane. Although this allele is found in only ∼4–5% of patients, a successful study could provide a needed proof of principle that mutant CFTR function could be a target for corrective drugs. Overall, numerous candidate compounds that might correct, activate and/or potentiate mutant CFTR alleles are currently in preclinical testing [94], which will hopefully provide some answers into the possible utility of this approach to CF lung disease.

Targeting the consequences of defective CFTR function

Other approaches that do not necessarily target CFTR directly (or ensuing lung infection and its consequences) are being pursued to alleviate the pathology that occurs in the CF lung. Four drugs that can restore proper salt transport are in phase II or phase III trials. One of these drugs, an agonist of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor that coordinates the process of mucociliary clearance in the lung, is being used to activate this receptor to promote the release of water and salt from various cells in the lungs [95]. Additionally, activation of the P2Y2 receptor on type II alveolar cells induces release of surfactant, which helps to maintain the integrity of the small airways. Another drug, Moli1901, works by increasing the activity of non-CFTR chloride channels, and there is evidence of clinical efficacy for these compounds [96]. Inhalation of hypertonic saline preceded by a bronchodilator [97,98] has recently been shown to improve lung function in CF patients with varying severities of lung disease, and as a result, there are now studies underway looking at the efficacy of hypertonic saline in infants with CF. Finally, numerous papers have recently appeared claiming to have identified genetic modifiers that influence the course of CF lung disease and thus are potential targets for clinical interventions [99]. However, most of the associations are not readily reproduced in multiple samples of CF patients, and even the most rigorously conducted investigation identifying polymorphisms in the transforming growth factor-β gene as being a modifier of CF lung disease severity [99] has not yet identified any molecular or cellular mechanism for which intervention strategies might be developed.

Of note, none of the pharmacologic interventions in various stages of investigation for CF lung disease have been evaluated on whether or not they will restore a high level of resistance to acquisition of P. aeruginosa infection by increasing the ability of mutant CFTR to recognize this pathogen. Thus, although the clinical consequences of infection might be delayed or the course of decline in lung function modified in a positive manner, the ability of any of the interventions to restore the integrity of the ASL might be insufficient to confer on CF patients the level of resistance to P. aeruginosa infection that is present in individuals with WT-CFTR. Although vaccination might be able to do this, most of these other strategies, whether directly targeting the viability of pathogens, improving host clearance or modulating the consequences of inflammation and virulence factor production, are unlikely to keep P. aeruginosa from recurrently infecting CF patients, unless these interventions also allow the CF host to establish a state of effective adaptive immunity. For the foreseeable future, CF patients are likely to spend a good portion of their lives undergoing their daily routine therapies, including the use of nebulizing drugs for hours every day, to minimize the consequences of lung infections. Consideration of how these activities can impact the disease, patient health, quality of life and compliance with prescribed therapies might be as important as finding new therapies based on sound molecular and cellular insights into the function of CFTR.

Concluding remarks and future directions

Understanding the basis for the hypersusceptibility to chronic P. aeruginosa infection in the vast majority of CF patients has progressed well since the identification of the CFTR gene in 1989 thanks to many outstanding studies that have identified various functions of the CFTR molecule. Among the better studied properties of CFTR is its role in regulating the integrity of the airway surface via regulation of sodium and chloride ion transport. Less well studied is the property of CFTR that is dependent upon amino acids 108–117, which allow this molecule to bind to the LPS outer core of P. aeruginosa and initiate a protective inflammatory response that is dysfunctional in CF. Components of the protective, CFTR-dependent response include (i) rapid release of IL-1 and signaling through the IL-1 receptor and the adaptor molecule MyD88 to initiate NF-κB nuclear translocation, (ii) formation of lipid rafts containing P. aeruginosa bound to CFTR, (iii) transcription of genes and production of proinflammatory proteins to recruit polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs) to the airway surface, (iv) elimination of P. aeruginosa by desquamation of epithelial cells with internalized bacteria and phagocytic killing by PMNLs and (v) resolution of infection via apoptosis of the epithelial cells and PMNLs that have encountered P. aeruginosa. Within the lipid raft are up to 150 proteins that are not found in lipid rafts of infected airway epithelial cells containing mutant-CFTR, and several of these, notably MVP [36], are key participants in fullfledged resistance to P. aeruginosa infection. Of importance, virtually all of the findings related to the recognition of P. aeruginosa by CFTR have been validated in appropriate animal models, are consistent with the analysis of infection in CF lung samples and explain why this one pathogen, P. aeruginosa, is the overwhelmingly dominant cause of morbidity and the life-shortening mortality due to respiratory failure in CF.

Nonetheless, many more experiments remain to be done to fully elucidate the pathologic consequences of CF lung infection (Box 3). One of the more important future experiments would be one to determine where the molecular and cellular divergence is between the effective, protective inflammatory responses to P. aeruginosa mediated by WT-CFTR and the infective, harmful inflammation that is unable to stop the chronic infection in the setting of CF. Another would be to define the full spectrum of CFTR activity and, furthermore, which properties of this molecule are essential for resistance to P. aeruginosa infection. Additionally, identifying and evaluating how molecules recruited to the lipid rafts of airway cells with WT-CFTR upon P. aeruginosa infection mediate the various host responses needed to clear this pathogen could provide leads for drugs to augment resistance to infection. More effective anti-P. aeruginosa therapies are needed, validated by evidence-based clinical trials, such as efficacy of early antibiotic interventions or further vaccine development. Connecting the persistence of P. aeruginosa with the properties of the CF lung in a more mechanistic way and determining why the pathogenesis of this organism in CF is unique and not exactly comparable to diseases such as ciliary dyskinesia would be of importance for both basic and applied research in CF. And identifying genetic modifiers of disease in a robust, reproducible fashion involving multiple populations, along with delineating which of the functional consequences of these polymorphisms leads to better lung function, is likely to lead to newer therapies for CF. These strategies, along with others not specifically mentioned, have high potential to identify new drug targets and new drugs to add to the armamentarium currently available for managing CF lung disease.

Box 3. Outstanding questions.

What is the molecular and cellular basis for the divergence of the protective, helpful inflammatory response of healthy invididuals and the non-protective, harmful inflammatory response of CF patients to P. aeruginosa? Are these druggable targets?

Can we determine which functions of CFTR are critical for resistance to P. aeruginosa, and can this resistance be enhanced by pharmacologic agents?

Can we identify critical molecular partners that function along with WT-CFTR to mediate high-level resistance to P. aeruginosa, and can we augment their activity to enhance resistance to infection in CF?

What properties of non-functional, mutant CFTR can be restored to enhance resistance to lung infection or modulate inflammation in a positive manner?

What are the best strategies for preventing, delaying or minimizing P. aeruginosa infection?

Which genetic modifiers of CF lung disease truly impact the rate of decline in lung function, how do they function and can polymorphisms giving better outcomes be effectively exploited for therapies?

Overall, much of what we have learned about the role of CFTR in susceptibility to P. aeruginosa infection and subsequent inflammation has led to the development of new drugs, new ways to use old drugs and an impressive array of potential pharmaceutical interventions aimed at dealing with the consequences of lung infection in CF. Although the prospects for a longer and better life for CF patients continually improve, a means to either completely prevent the hypersusceptibility to P. aeruginosa infection without serious consequences, such as development of more-severe infections, or an actual cure for CF through a proper intervention such as gene therapy, remain in the distance for now. Obviously, the large commitment to research into this disease has been the force behind the development of many therapeutics for this condition, as well as providing exciting and stimulating insights into basic human physiology. One might argue that CF is the premier example of a complex and complicated human disease wherein understanding of the genetic, molecular and cellular defects have driven basic and applied research to the highest level, resulting in tangible benefits for patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all of the individuals who have conducted research and generated results cited in this review, thereby helping to provide insight into the pathogenesis of CF lung disease and the role of the airway epithelium. Specific funding for the authors has come from the following sources: the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants ‘Acquired immunity and vaccination for P. aeruginosa’, ‘Virulence and immunity to mucoid P. aeruginosa’ and ‘CFTR and infection in cystic fibrosis patients’; the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; and an Interdisciplinary Research Seed Grant from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA. C.P-B. is currently supported by an award from the Fonds de la recherche en santédu Québec.

References

- 1.Li Z, et al. Longitudinal development of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and lung disease progression in children with cystic fibrosis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2005;293:581–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emerson J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other predictors of mortality and morbidity in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2002;34:91–100. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parad RB, et al. Pulmonary outcome in cystic fibrosis is influenced primarily by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and immune status and only modestly by genotype. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:4744–4750. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4744-4750.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pier GB, et al. Opsonophagocytic killing antibody to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide in older, non-colonized cystic fibrosis patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987;317:793–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709243171303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baltimore RS, et al. Immunohistopathologic localization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in lungs from patients with cystic fibrosis -Implications for the pathogenesis of progressive lung deterioration. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1989;140:1650–1661. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.6.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeffery PK, Brain PR. Surface morphology of human airway mucosa: normal, carcinoma or cystic fibrosis. Scanning Microsc. 1988;2:553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worlitzsch D, et al. Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:317–325. doi: 10.1172/JCI13870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder TH, et al. Transgenic cystic fibrosis mice exhibit reduced early clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the respiratory tract. J. Immunol. 2001;166:7410–7418. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esen M, et al. Invasion of human epithelial cells by Pseudomonas aeruginosa involves src-like tyrosine kinases p60Src and p59Fyn. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:281–287. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.281-287.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong F, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyocyanin inactivates lung epithelial vacuolar ATPase-dependent cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression and localization. Cell. Microbiol. 2006;8:1121–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pier GB, et al. Role of mutant CFTR in hypersusceptibility of cystic fibrosis patients to lung infections. Science. 1996;271:64–67. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5245.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeder TH, et al. CFTR is a pattern recognition molecule that extracts Pseudomonas aeruginosa LPS from the outer membrane into epithelial cells and activates NF-kappa B translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:6907–6912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092160899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boucher RC. New concepts of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2004;23:146–158. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00057003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morillas HN, et al. Genetic causes of bronchiectasis: primary ciliary dyskinesia. Respiration. 2007;74:252–263. doi: 10.1159/000101783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poletti V, et al. Diffuse panbronchiolitis. Eur. Respir. J. 2006;28:862–871. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00131805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyczak JB, et al. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002;15:194–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.194-222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treggiari MM, et al. Approach to eradication of initial Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2007;42:751–756. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell SC, Robinson PJ. Exacerbations in cystic fibrosis: 2 – Prevention. Thorax. 2007;62:723–732. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.060897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liou TG, et al. Lung transplantation and survival in children with cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:2143–2152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilsson P, Ripa T. Staphylococcus aureus throat colonization is more frequent than colonization in the anterior nares. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:3334–3339. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00880-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratjen F, Doring G. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2003;361:681–689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jelsbak L, et al. Molecular epidemiology and dynamics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations in lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:2214–2224. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01282-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott FW, Pitt TL. Identification and characterization of transmissible Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains in cystic fibrosis patients in England and Wales. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004;53:609–615. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry RL, et al. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a marker of poor survival in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 1992;12:158–161. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950120306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith EE, et al. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:8487–8492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith JJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis airway epithelia fail to kill bacteria because of abnormal airway surface fluid. Cell. 1996;85:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pier GB, et al. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is an epithelial cell receptor for clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:12088–12093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiniger N, et al. Resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic lung infection requires cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-modulated interleukin-1 (IL-1) release and signaling through the IL-1 receptor. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:1598–1608. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01980-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiniger N, et al. Influence of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator on gene expression in response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of human bronchial epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:6822–6830. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6822-6830.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cannon CL, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced apoptosis is defective in respiratory epithelial cells expressing mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003;29:188–197. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kowalski MP, Pier GB. Localization of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator to lipid rafts of epithelial cells is required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced cellular activation. J. Immunol. 2004;172:418–425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riethmuller J, et al. Membrane rafts in host-pathogen interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:2139–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arora SK, et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellar cap protein, FliD, is responsible for mucin adhesion. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1000–1007. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1000-1007.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez-Ortega C, Harwood CS. Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to low oxygen indicate that growth in the cystic fibrosis lung is by aerobic respiration. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65:153–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bragonzi A, et al. Nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa expresses alginate in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis and in a mouse model. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192:410–419. doi: 10.1086/431516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kowalski MP, et al. Host resistance to lung infection mediated by major vault protein in epithelial cells. Science. 2007;317:130–132. doi: 10.1126/science.1142311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feuillet V, et al. Involvement of Toll-like receptor 5 in the recognition of flagellated bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:12487–12492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Power MR, et al. The development of early host response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection is critically dependent on myeloid differentiation factor 88 in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49315–49322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402111200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramphal R, et al. TLRs 2 and 4 are not involved in hypersusceptibility to acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3927–3934. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balloy V, et al. The role of flagellin versus motility in acute lung disease caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196:289–296. doi: 10.1086/518610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skerrett SJ, et al. Cutting edge: myeloid differentiation factor 88 is essential for pulmonary host defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa but not Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 2004;172:3377–3381. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coleman FT, et al. Hypersusceptibility of cystic fibrosis mice to chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa oropharyngeal colonization and lung infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:1949–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437901100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. On regulation of phagosome maturation and antigen presentation. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:1029–1035. doi: 10.1038/ni1006-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah DS, et al. The flagellar filament of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: pH-induced polymorphic transitions and analysis of the fliC gene. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:5218–5224. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5218-5224.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolfgang MC, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulates flagellin expression as part of a global response to airway fluid from cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:6664–6668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307553101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jyot J, et al. Genetic mechanisms involved in the repression of flagellar assemblybyPseudomonas aeruginosa in human mucus. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1026–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demko CA, et al. Gender differences in cystic fibrosis: Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995;48:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00230-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boucher JC, et al. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:3838–3846. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3838-3846.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin DW, et al. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:8377–8381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ciofu O, et al. Investigation of the algT operon sequence in mucoid and non-mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from 115 Scandinavian patients with cystic fibrosis and in 88 in υitro non-mucoid revertants. Microbiology. 2008;154:103–113. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/010421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anthony M, et al. Genetic analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the sputa of Australian adult cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:2772–2778. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.2772-2778.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer KL, et al. Nutritional cues control Pseudomonas aeruginosa multi-cellular behavior in cystic fibrosis sputum. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:8079–8087. doi: 10.1128/JB.01138-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donaldson SH, Boucher RC. Update on pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2003;9:486–491. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hancock REW, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis: A class of serum-sensitive, nontypable strains deficient in lipopolysaccharide O side-chains. Infect. Immun. 1983;42:170–177. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.170-177.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ernst RK, et al. Unique lipid a modifications in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from the airways of patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196:1088–1092. doi: 10.1086/521367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doring G, et al. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzymes in lung infections of patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect. Immun. 1985;49:557–562. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.3.557-562.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fomsgaard A, et al. Antibodies from chronically infected cystic fibrosis patients react with lipopolysaccharides extracted by new micromethods from all serotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . APMIS. 1993;101:101–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1993.tb00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang L, et al. In situ growth rates and biofilm development of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations in chronic lung infections. J. Bacteriol. 2007;21:21. doi: 10.1128/JB.01581-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sandoz KM, et al. From the cover: social cheating in Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:15876–15881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705653104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hogardt M, et al. Sequence variability and functional analysis of MutS of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;296:313–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ventre I, et al. Multiple sensors control reciprocal expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulatory RNA and virulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:171–176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507407103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rowe SM, Clancy JP. Advances in cystic fibrosis therapies. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2006;18:604–613. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3280109b90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Driscoll JA, et al. The epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Drugs. 2007;67:351–368. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hagerman JK, et al. Tobramycin solution for inhalation in cystic fibrosis patients: a review of the literature. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2007;8:467–475. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]