Abstract

The objective of this work was to determine whether overweight/obesity is a risk factor for cerebrovascular disease in children. The study included 53 children with non–neonatal-onset cerebral sinovenous thrombosis or arterial ischemic stroke. The prevalence of overweight/obesity was compared between this cohort and healthy children from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. In addition, cerebral sinovenous thrombosis patients were compared to a group of matched hospitalized controls. The prevalence of overweight/obesity was significantly higher in the cerebral sinovenous thrombosis cohort (55%), but not the arterial ischemic stroke cohort (36%), relative to national controls (32%; P = .04 and P = .81, respectively). Similarly, the prevalence of overweight/obesity was significantly higher in the cerebral sinovenous thrombosis cohort than in Colorado controls (25%; P = .02). In conclusion, the prevalence of overweight/obese was significantly increased in cerebral sinovenous thrombosis patients as compared to both national and local controls. Results should be evaluated in a larger multi-institutional cohort.

Keywords: obesity, arterial ischemic, stroke, cerebral sinovenous thrombosis, overweight

The association between adult obesity and cerebrovascular disease, specifically arterial ischemic stroke and cerebral sinovenous thrombosis, is well characterized. Multiple studies report that elevated body mass index is an independent risk factor for arterial ischemic stroke in adults.1,2 Similarly, elevated body mass index serves as a risk factor for venous thromboembolism in adults.3 The risk factors for cerebral sinovenous thrombosis and arterial ischemic stroke in children are well described in several cohorts.4–6 Although thrombophilia is well characterized by multiple studies as a risk factor for childhood arterial ischemic stroke,7 and recent studies have established a relationship between thrombophilia and obesity,8 few studies have investigated the influence of body mass index as a risk factor for childhood vascular disease.9

Given that obesity is increasingly prevalent in children10 and is associated with venous thromboembolism and arterial ischemic stroke in adults, the objective of this current work was to determine whether overweight/obesity is a risk factor for cerebrovascular disease in children.

Patients and Methods

Data on height, weight, and presenting characteristics were prospectively collected on children between the ages of 2 to 18 years (inclusive) with clinically diagnosed and radiologically confirmed cerebral sinovenous thrombosis (n = 23) or arterial ischemic stroke (n = 30) enrolled in an institutional review board–approved institution-based prospective inception cohort study between August 2006 and August 2009 at the Children’s Hospital, Colorado (Aurora, Colorado, USA). Body mass index was calculated using the most recent height and weight available within 4 weeks of hospital admission. Thrombotic characteristics were analyzed for each study participant in the arterial ischemic stroke and cerebral sinovenous thrombosis cohorts in order to classify the participants into 3 groups: no thrombophilia, potent thrombophilia, and mild thrombophilia. Potent thrombophilia included any one of the following: (1) severe anticoagulant deficiency (<30% antithrombin; <20% protein C or protein S); (2) homozygosity for the factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A polymorphisms; (3) antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; or (4) multitrait (>1) thrombophilia. All other thrombophilia states were characterized as “mild thrombophilia.”

Children with potential body mass index confounders, including congenital heart disease (n = 5) and cancer (n = 1), were excluded from the cohort analysis. Body mass index percentiles adjusted for age and sex were generated using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts.11 Body mass index percentiles were then classified into the following categories adjusted for age and sex: (1) overweight/obesity: body mass index ≥85th percentile and (2) normal/underweight: body mass index <85th percentile.

Prevalence of overweight/obesity was compared between cohort patients and each of 2 control groups: (1) healthy children, aged 2 to 19 years, from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted in 2007–2008 (n = 3281) and (2) contemporaneously hospitalized controls without cerebral sinovenous thrombosis, congenital heart disease, or cancer. Control patients were matched by age and sex, in a 1:3 case–control ratio, to cohort patients with cerebral sinovenous thrombosis (for cerebral sinovenous thrombosis comparison only). For each comparison, 2-tailed chi-square analysis with Yates correction was performed. Body mass index distributions were compared between Children’s Hospital, Colorado, cerebral sinovenous thrombosis cases and hospitalized controls via a mixed model Student t test.

Results

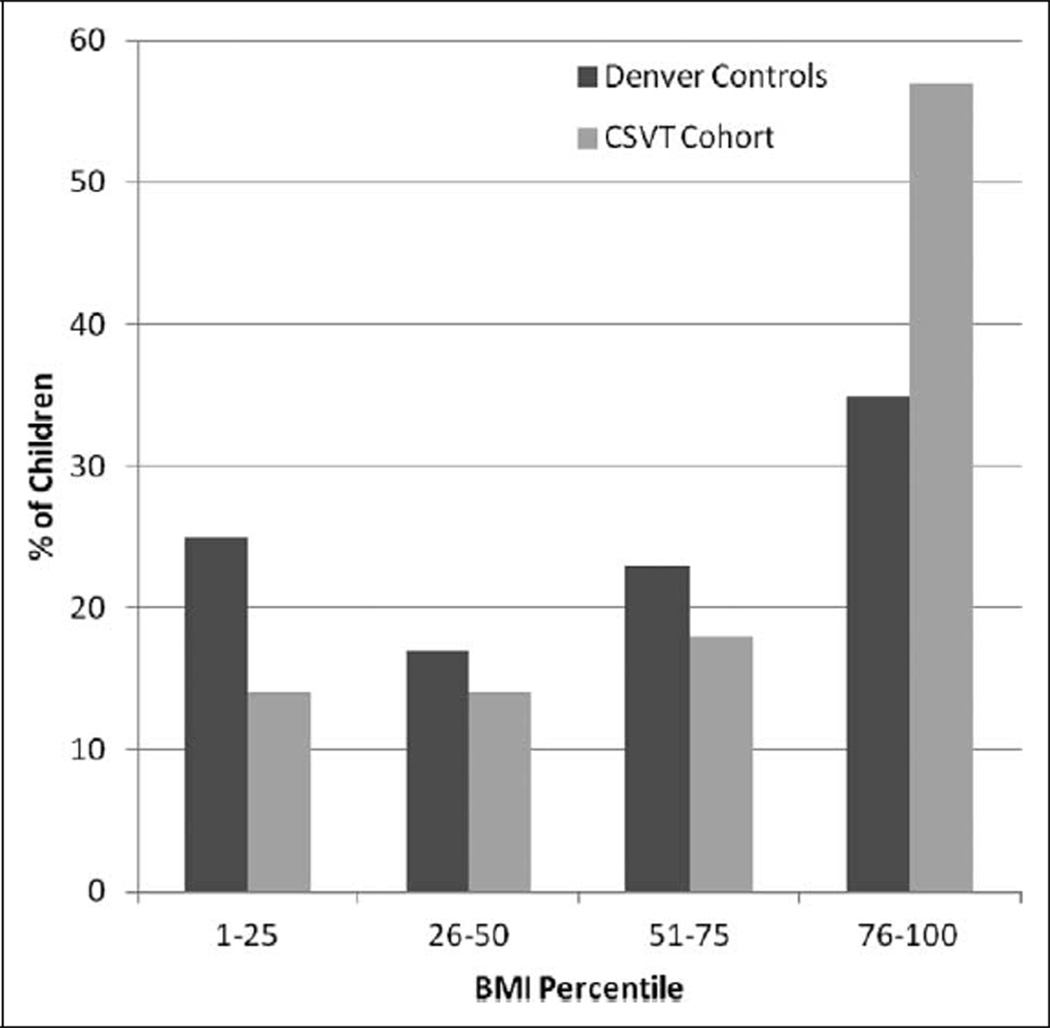

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the patient cohort are given in the table. Overweight/obesity was significantly higher in cerebral sinovenous thrombosis patients relative to both the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey controls (P = .04) and the Colorado controls (P = .02). In contrast, the prevalence did not differ between the arterial ischemic stroke patients and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey controls (P = .81). As demonstrated in the figure, there was a tendency toward higher body mass index percentile in cerebral sinovenous thrombosis patients (mean = 69.6%, SE = 6.65) compared to Colorado controls (mean = 54.7%; SE = 3.78; P = .06). There were no significant differences in thrombophilia characteristics between the 2 cohorts.

Table 1.

Age, Sex, Thrombophilia, and BMIa Characteristics of Childhood AIS Patients, Childhood CSVT Patients, and NHANES Controls.

| Childhood AIS |

Childhood CSVT |

NHANES Controls |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 25 | 22 | 3281 |

| Age, y, at diagnosis, median (range) | 11.7 (2–17) | 12 (2–17) | (2–19) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 21 (84) | 11 (50) | N/A |

| Thrombophilia findings, n(%)b | N/A | ||

| Mild thrombophilia | 9 (36) | 4 (18) | |

| Potent thrombophilia | 11 (44) | 16 (73) | |

| Total (any thrombophilia) | 20 (80) | 20 (91) | |

| Prevalence of overweight/obesity, n (%) | 9 (36)* | 12 (55)† | 1040 (32) |

Abbreviations: AIS, arterial ischemic stroke; BMI, body mass index; CHC, Children’s Hospital, Colorado; CSVT, cerebral sinovenous thrombosis; IQR, Interquartile range; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

BMI percentile is adjusted for age and sex.

“Potent thrombophilia” was defined by any one of the following: (1) severe anticoagulant deficiency (<30% antithrombin; <20% protein C or protein S); (2) homozygosity for the factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A polymorphisms; (3) antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; or (4) multitrait (>1) thrombophilia. All other thrombophilia states were characterized as “mild thrombophilia.”

P = .81 (when comparing CHC AIS cohort to NHANES data).

P = .04 (when comparing CHC CSVT cohort to NHANES data).

Figure 1.

Body mass index distribution in CSVT cases vs age- and sex-matched controls. BMI, body mass index; CSVT, cerebral sinovenous thrombosis.

Discussion

The present findings, from a single-institution prospective cohort of children with cerebrovascular disease, indicate that prevalence of overweight/obesity is increased in those with cerebral sinovenous thrombosis in comparison to both National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey pediatric norms and contemporaneous, hospitalized local controls. This observation is supported by previous data demonstrating overweight/obesity as a modest risk factor for adult venous thromboembolism.3 Although previous publications have postulated an association between childhood overweight/obesity and cerebral sinovenous thrombosis,9 none have directly addressed the relationship between childhood overweight/obesity and cerebral sinovenous thrombosis, presumably because of a lack of statistical power.

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying an association between overweight/obesity and thrombogenesis have not yet been clearly defined. Hypofibrinolytic states and an associated elevation in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 among overweight adults with cerebral sinovenous thrombosis have been shown, but this relationship is still controversial.12 Additionally, recent studies have demonstrated a relationship between obesity and a prothrombotic state.8 Potential factors, including protein C resistance, elevated levels of factor VIII, and markers of inflammation, should be investigated in obese children with cerebral sinovenous thrombosis.

The principal limitation of the present study is the relatively small patient cohort, which is susceptible to bias. Additionally, given the single-institutional site of the study and small sample size, the findings may not be generalizable to other geographical locations and are best applied to clinical populations exhibiting demographic characteristics similar to those observed in our cohort. As an example of this, males are likely overrepresented in the arterial ischemic stroke cohort (number of males: 21/25, 84%). For these reasons, substantiation of these results in broader patient populations is warranted.

Acknowledgments

NAG and TJB are supported in part by Career Development Awards from NIH/NHLBI (1K23HL084055 and 1K23HL096895). MJMJ is supported in part by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (UR6/CCU820552). NFK is supported in part by a grant from NIH/NIDDK (9K24 DK083772). This work was presented in part at the 2010 International Stroke Conference, San Antonio, Texas.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

TJB, CR, and VP completed the first draft of the manuscript. VP and CR contributed equally to this text. NK, VP, CR, MMJ, NG, and TB all participated in the design and analysis of this manuscript. MMJ, TB, and NG enrolled patients. CR, VP, and TB drafted the original manuscript, and all authors made substantial editorial contributions to the final draft. All authors approved the final submitted manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All patients were consented into an Institutional-based cohort study of acute childhood-onset AIS at The Children’s Hospital Denver between January 1, 2005, and May 1, 2009 (Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board studies 05-0339 and 04-1107).

References

- 1.Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Rexrode KM, et al. Prospective study of body mass index and risk of stroke in apparently healthy women. Circulation. 2005;111:1992–1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161822.83163.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jood K, Jern C, Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A. Body mass index in mid-life is associated with a first stroke in men: a prospective population study over 28 years. Stroke. 2004;35:2764–2769. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000147715.58886.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Severinsen MT, Kristensen SR, Johnsen SP, et al. Anthropometry, body fat, and venous thromboembolism: a Danish follow-up study. Circulation. 2009;120:1850–1857. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeVeber G, Andrew M, Adams C, et al. Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis in children. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:417–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108093450604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganesan V, Prengler M, McShane MA, et al. Investigation of risk factors in children with arterial ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:167–173. doi: 10.1002/ana.10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasay M, Dai AI, Ansari M, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in children: a multicenter cohort from the United States. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:26–31. doi: 10.1177/0883073807307976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenet G, Lütkhoff LK, Albisetti M, et al. Impact of thrombophilia on risk of arterial ischemic stroke or cerebral sinovenous thrombosis in neonates and children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Circulation. 2010;121:1838–1847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.913673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaye SM, Pietiläinen KH, Kotronen A, et al. Obesity-related derangements of coagulation and fibrinolysis: a study of obesity-discordant monozygotic twin pairs. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:88–94. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heller C, Heinecke A, Junker R, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis in children: a multifactorial origin. Circulation. 2003;108:1362–1367. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087598.05977.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/

- 12.Quattrone A, Gambardella A, Carbone AM, et al. A hypofibrinolytic state in overweight patients with cerebral venous thrombosis and isolated intracranial hypertension. J Neurol. 1999;246:1086–1089. doi: 10.1007/s004150050517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]