Abstract

Bacterial swarming is a type of motility characterized by a rapid and collective migration of bacteria on surfaces. Most swarming species form densely packed dynamic clusters in the form of whirls and jets, in which hundreds of rod-shaped rigid cells move in circular and straight patterns, respectively. Recent studies have suggested that short-range steric interactions may dominate hydrodynamic interactions and that geometrical factors, such as a cell's aspect ratio, play an important role in bacterial swarming. Typically, the aspect ratio for most swarming species is only up to 5, and a detailed understanding of the role of much larger aspect ratios remains an open challenge. Here we study the dynamics of Paenibacillus dendritiformis C morphotype, a very long, hyperflagellated, straight (rigid), rod-shaped bacterium with an aspect ratio of ∼20. We find that instead of swarming in whirls and jets as observed in most species, including the shorter T morphotype of P. dendritiformis, the C morphotype moves in densely packed straight but thin long lines. Within these lines, all bacteria show periodic reversals, with a typical reversal time of 20 s, which is independent of their neighbors, the initial nutrient level, agar rigidity, surfactant addition, humidity level, temperature, nutrient chemotaxis, oxygen level, illumination intensity or gradient, and cell length. The evolutionary advantage of this unique back-and-forth surface translocation remains unclear.

INTRODUCTION

Motile bacteria are able to colonize surfaces using various motility mechanisms (1). One efficient method includes flagellation-based cell motion in conjunction with collective lubrication (typically by secretion of surfactants) to enable fast expansion on hard surfaces. This mode of “bacterial swarming” that has been studied extensively for many species (1–15) enables rapid colony expansion (up to centimeters per hour). Swarming is often marked by hundreds of cells moving in a coordinated fashion while generating whirl and jet patterns.

Studies of the collective dynamics of swarming have examined multiple aspects of motility. On the macroscopic level, it was discovered that swarming colonies show an advantage over liquid cultures in that they exhibit an increased resistance to antimicrobials (1, 4, 5, 15–20). Studies of collective secretions of signaling and quorum-sensing molecules have shown how interactions between cells in swarming colonies are controlled (11) and exposed the identification of associated genetic manipulations and upregulated proteins that control biosurfactant secretions and flagellar behavior. On the single-cell level, attention was given to swarm cell trajectories and the ways in which these trajectories are determined by flagellar motion (8, 21–23). A combination of experiments (2, 3, 14, 15, 24–38) and theory (39–43) suggests that hydrodynamic interactions play a significant role in this social form of migration.

Hydrodynamic interactions may not always be the dominant physical mechanism controlling bacterial motion. During differentiation to the swarming state, the cells of most species elongate and are thus subjected to strong steric and excluded volume interactions (29, 44, 45). The cells are typically considered self-propelled rods, having a straight rigid body; i.e., no cell bending is observed by light microscopy (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). For very long cells, this may affect the self-organization and change the dynamic patterns. The result is that the very long straight bacteria may no longer swarm in whirls and jets (45). In a recent study on collective motion of Bacillus subtilis in liquids (29), clusters of bacteria with high orientational order have locally high swimming speeds while orientationally disordered regions have lower speeds. The body length/width ratio plays an important role in the explanations offered for the mode of collective motion (45), but since most swarmers in nature are self-propelled straight rods and have a body length/width ratio of up to ∼5 (∼10 for two daughter cells before reproduction is completed), swarming of longer (e.g., length/width ratio of >20 of a single cell) straight rods was never studied experimentally. Recently, Tuson et al. (46) studied the dynamics of Proteus mirabilis, a long (length/width ratio of >20) swarming species, and observed that it moves in whirls and jets similarly to short (aspect ratio, ∼5) and straight species. However, because these cells are curved and bent during swarming (they typically look like boiled spaghetti [46]), they do not fall under the category of self-propelled rods, i.e., straight (rigid) bacterial cells (45). In our study, we see that the rods do not bend even during collisions (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

In this study, we quantitatively examine the swarming dynamics of very long rods using Paenibacillus dendritiformis morphotype C (47). Surprisingly, we find that instead of the standard dynamic patterns of whirls and jets, observed in shorter species (e.g., B. subtilis [2]) and, in particular, the shorter morphotype of P. dendritiformis (morphotype T) (3, 14), P. dendritiformis morphotype C forms long tracks in which individual bacteria repeatedly move back and forth along moderately curved lines. Direction switching is periodic, and each cell reverses (backs up) on average approximately every 20 s, independently of its neighbors. The time between switching was found to be independent of initial nutrient level, agar rigidity, surfactant additions, cell length (a broad length distribution of ∼17 ± 12 μm and a fixed width of ∼1 μm are always present in a normal culture), humidity level, temperature, food chemotaxis, and oxygen level. This independence of reversal times suggests an extraordinary robust internal clock for reversal events. The observed periodic reversals are different from those observed for other species, such as Myxococcus xanthus (48–52), Halobacterium salinarum (53, 54), and Acetobacter xylinum (55), in that the motive organelles are different. We thus report a new behavior for swarming motility: periodic reversals in very long and rigid hyperflagellated bacteria. This unique behavior is so far limited to P. dendritiformis. The generality of this type of swarming is yet to be known, as is the general correlation to cell aspect ratio.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain and growth medium.

Paenibacillus dendritiformis (morphotype C; also known as the chiral morphotype) is a spore-forming, motile bacterial species (56). Each bacterium is an elongated (filamentous), rigid (seldom bends by collisions), rod-shaped cell, with a fixed thickness of ∼1 μm and a very broad length distribution of ∼17 ± 12 μm. The bacteria were maintained at −80°C in Luria broth (LB) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with 25% (wt/vol) glycerol. Luria broth was inoculated with the frozen stock and grown for 24 h at 30°C while being shaken; it was subsequently grown to an optical density at 650 nm (OD650) of 0.8, corresponding to approximately 1 × 107 bacteria/ml (calibrated by counting colonies on agar after appropriate dilution).

The agar plates were prepared as follows: peptone medium contained NaCl (5 g/liter), K2HPO4 (5 g/liter), and Bacto Peptone (Becton, Dickinson) in the range of 0.5 to 8 g/liter. Either Eiken (Tokyo, Japan) or Difco (Becton, Dickinson) agar was added at a concentration of 0.7 to 1.5% (wt/vol). Twelve milliliters of molten agar was poured into 8.8-cm-diameter petri plates, which were dried for 4 days at 25°C in 50% relative humidity (RH) until the weight decreased by 1 g. Similar plates were prepared with addition of 0.0006% (wt/vol) Brij 35. At these concentrations, Brij 35 was found to not affect bacterial metabolism; however, it does reduce the surface tension of the colony, enabling faster colonial expansion. Nutrient-rich plates were prepared by mixing 2.5% (wt/vol) Luria broth with agar in the concentrations noted; 25 ml of molten agar was poured into similar plates and dried for 24 h.

Some peptone plates were used to grow colonies at higher and lower oxygen levels. The plates were inserted, after inoculation, into plastic bags filled with pure oxygen or with pure nitrogen. In other cases, the colonies were exposed to oxygen or nitrogen only at the time of observation by bounding the microscope stage area with a cell to which the gases were streamed. This was done because the bacteria can adapt to a certain oxygen level; however, a rapid change of oxygen in the course of observation might produce a strong effect on the reversal rates and on the speed (57). Nutrient chemotaxis experiments were performed on plates that were kept slightly tilted while the agar was cooling.

A motility buffer was used to move cells from the agar into liquid. The motility buffer was made of 0.067 M sodium chloride, 0.01 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), 0.01 M sodium lactate, 10−4 M EDTA, and 10−6 M l-methionine.

Colonial expansion.

The agar plates were inoculated by placing 5-μl droplets of the culture at the center of the plate. The plates were mounted on a rotating stage inside a 1-m3 chamber typically maintained at 30.0°C ± 0.5°C and 90% ± 2% RH (58). Some experiments were performed at other temperatures (25 to 40°C) and humidities (35 to 90% RH). The rotating stage system enabled us to monitor growth development of 10 plates simultaneously; the rotation has no influence on any of the bacterial properties. The stage was controlled by a stepper motor that stops sequentially for each bacterial colony to be imaged. A rotation period of 1 h was sufficiently short to capture the growth of the colony. The reproducibility of positioning of the agar plates was ±15 μm, allowing successive images of a given colony to be subtracted to determine growth patterns. Images were obtained with a 10-megapixel Nikon D200 camera with a 60-mm lens. The camera was placed above the rotating stage and was programmed to take an image and store the data when a sample was stationed below it. For plates imaged only at a single point in time, colonies were stained with 0.1% (wt/vol) Coomassie brilliant blue to obtain higher-contrast images than those obtained in the sequences of images.

Microscopic measurements.

An optical microscope (Olympus IX50) equipped with LD 60× phase contrast (PH2) and LD 20× phase contrast (PHC) objective lenses was used to follow the microscopic motion. The microscope was placed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment. A digital camera captured the microscopic motion at a rate of 60 frames per second and a spatial resolution of 1,000 by 1,000 pixels. Images were taken for 5-min periods, resulting in 18,000 images in a sequence. Tracking bacterial motion was done manually, using a program called Tracker by Douglas Brown (http://www.cabrillo.edu/∼dbrown/tracker/).

Electron microscopy.

We used an FEI Tecnai transmission electron microscope (TEM) operated at 80 kV. The long, rod-shaped cells were collected from the agar using different methods and placed on 400-mesh copper carbon grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Flagella were lost in most cases. The best results were obtained by gently stamping the grids on the live colony at the region of interest for 1 s and then lifting the grid. The sample was immediately stained with 0.5% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate for 10 s, which fixes the cells and flagella in the state they were in at the time of contact with the grid.

RESULTS

Growth under canonical conditions.

In this section, we describe the colony developments under intermediate conditions (2 g/liter peptone, 1% [wt/vol] agar, 30°C, and 90% RH), which are considered to be the canonical or typical conditions for the development of P. dendritiformis chiral morphotype C colonies.

Colony expansion.

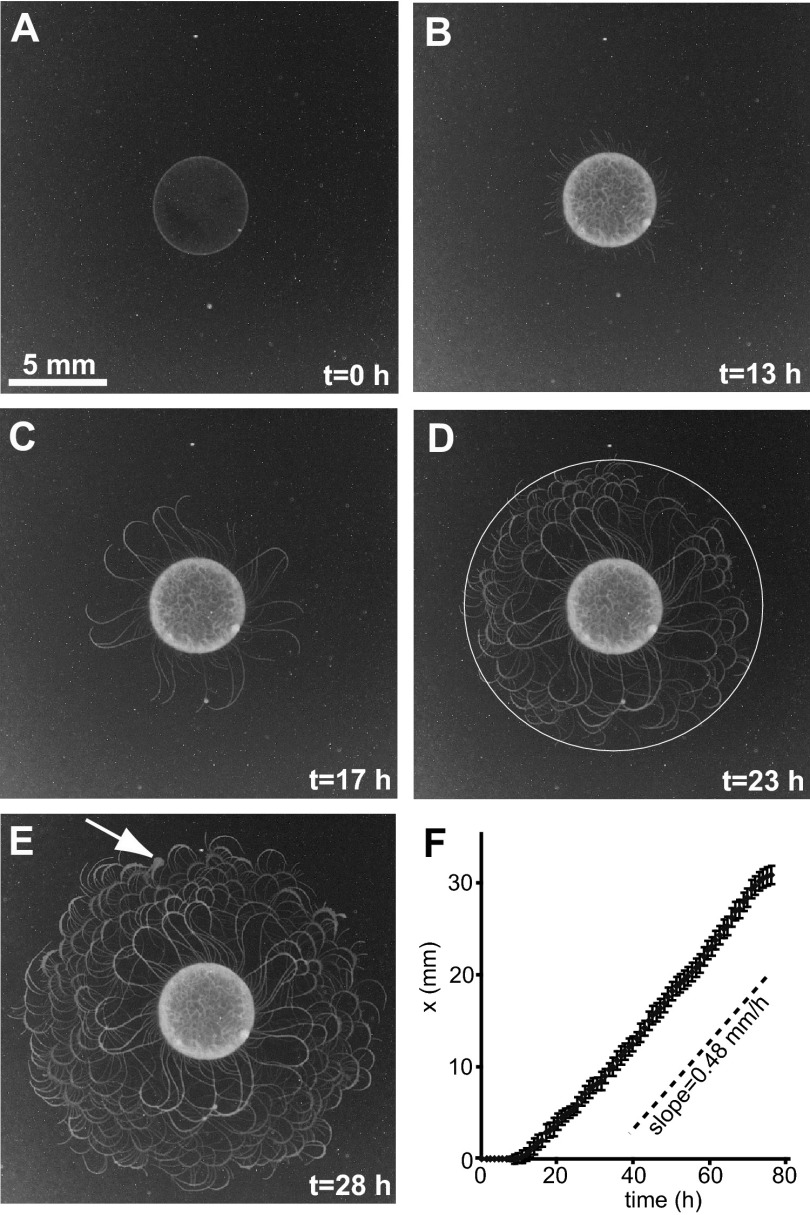

Colonial development involves the following stages: (i) an incubation lag time of 11 h, during which bacteria reproduce in the center of the inoculation, producing a “mother colony” (Fig. 1A and B), (ii) sprouting of leading (pioneering) branches from the mother colony (Fig. 1B), and (iii) colony expansion. The colony expands on the surface by sending out thin curved branches (curly branches with well-defined handedness), forming intricate branched patterns within a well-defined circular envelope (Fig. 1C to E). Several thin branches, on the rim of the circle of inoculation, start to stem perpendicularly to the rim and expand outward. For several hours, the branches continuously curl clockwise (colony faces up, agar faces down) and with the same speed grow back toward the circle of the inoculation, ending at (or crossing) the neighboring curly branch. During this growth, the branches become wider and newly formed curly branches stem from both the circle of inoculation and the older branches, forming a complex pattern (Fig. 1E). The expansion rate was estimated by measuring the speed of an imaginary circular envelope surrounding the colony. The speed of the growing envelope, 0.48 mm/h, is isotropic and constant, as illustrated by the straight line in Fig. 1F. The time development of such a colony is presented in Movie S1 in the supplemental material.

Fig 1.

Macroscopic colonial expansion of P. dendritiformis morphotype C bacteria. (A to E) Different stages of growth. (A) At t = 0 h, initial inoculation; (B) at t = 13 h, the spot inoculation is brighter and a few branches have stemmed from the spot rim; (C) at t = 17 h, the curly branches grow back toward the circle of the inoculation, ending at (or crossing) the neighbor curly branch; (D) at t = 23 h, the branches become wider and newly born curly branches stem from both the circle of inoculation and the older branches; (E) at t = 28 h, the complex growth continues. The arrow indicates a small region of morphotype T cells (that spontaneously switched from the C morphotype) that exhibit whirl and jet swarming patterns at the microscopic level. (F) The macroscopic expansion speed (0.48 mm/h) is indicated by the slope of a plot of the position of the imaginary envelope (x) as a function of time. The expanding envelope has concentric circles at time intervals for each colony. The radii are determined by following the farther tip of the colony at each time step (see circle in panel D). The error bars indicate the standard deviations for measurements for 10 colonies. Growth conditions are 2 g/liter peptone, 1% (wt/vol) Difco agar, 30°C, and 90% RH.

Cellular motility.

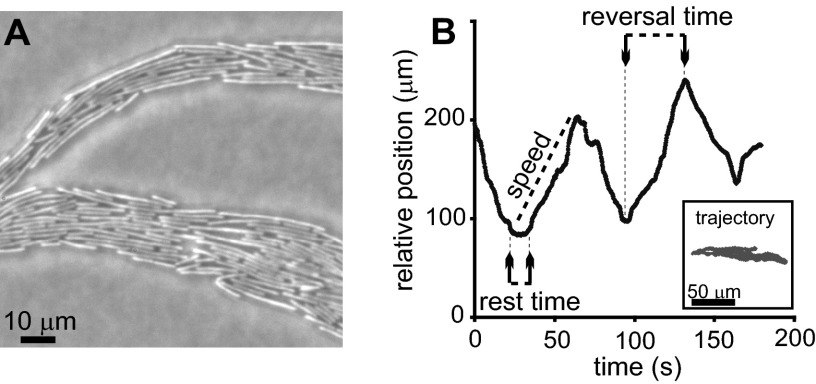

A closer look at the tips of the growing branches reveals that the long bacteria exhibit a back-and-forth swarming (moving back and forth), mostly aligned parallel to their neighbors due to orientation interactions (47) (see Movie S2 in the supplemental material). However, instead of the classical pattern of clusters of cells, here each cell was found to move solitarily. At the outer parts of the colony, they form a monolayer in which roughly 10 bacteria lie next to one another (Fig. 2A). A typical trajectory of a single bacterium among its neighbors is shown in Fig. 2B. Data were collected for single bacteria, located at the middle of the branch, until they exited the field of view. Between reversal events, a bacterium's microscopic speed is fairly constant and remains the same after it reverses direction. We define the reversal time as the time between switching events, set between the point in time at which the bacterium begins moving and the point in time at which it stops and changes direction. Reversal times for a single bacterium are typically the same, but statistics for the same bacterium are limited, as they tend to leave the field of view after fewer than about 6 reversal events. Cells tend to exit the field of view in the direction of colonial spreading (see moderate tendency in Fig. 2B). The cells typically rest for a few seconds (“rest time”) before they start moving in the opposite direction (Fig. 2B).

Fig 2.

Microscopic reversals of a single cell. (A) Microscopic picture of the outer parts of a colony. The cells form a monolayer in which roughly 10 bacteria lay one next to the other. Bacterial length distribution is broad; some cells are very long (∼ 40 μm), and some are much shorter (∼5 μm). (B) Relative position (with respect to some arbitrary fixed point on the agar) of a single cell in a colony as a function of time. Reversal time is defined as the time between the point at which the bacterium begins moving and the point at which it stops changing direction. A trajectory of the bacterium is shown in the inset. Growth conditions are 2 g/liter peptone, 1% (wt/vol) Difco agar, 30°C, and 90% RH.

Speed and reversal time.

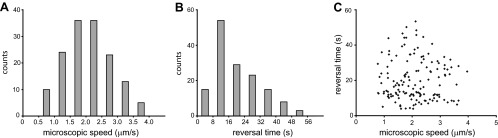

To gain a better understanding of what determines the reversal times, we analyzed 45 bacterial cells under the same growth conditions (canonical growth conditions of 2 g/liter peptone and 1% [wt/vol] agar, 30°C, and 90% RH). About 15 cells were tracked in a field of view, and the experiment was repeated 3 times. All tracked cells were located at the middle of the branch. A total of 150 reversal events were observed. The average value for the bacterial microscopic speed was 2.1 ± 0.7 μm/s, and the average reversal time was 20.0 ± 11.1 s with a positive skew. Figure 3A and B show a distribution for microscopic bacterial speeds and reversal times for 150 data points. A plot of reversal time versus microscopic speed (Fig. 3C) shows no obvious correlation (P = 0.004), and we conclude that the reversal time is independent of bacterial microscopic speed. We also found that the values for both the microscopic speed and the reversal time are constrained within some fixed boundaries. For instance, under canonical growth conditions, bacteria never travel slower than 0.8 μm/s or faster than 4.0 μm/s and never switch direction sooner than 4.0 s after a previous reversal.

Fig 3.

Microscopic speeds and reversal times of many bacteria under the same growth conditions (2 g/liter peptone, 1% [wt/vol] Difco agar, 30°C, and 90% RH). (A) Microscopic speed distribution for 150 data points; a quite large range of speeds is observed, with an average of 2 ± 0.7 μm/s. (B) Reversal time distribution for 150 data points; a quite large range of reversal times is observed, with an average of 20 ± 11 s. (C) Reversal time as a function of microscopic speed shows no correlation. All values for both the microscopic speeds and the reversal times are constrained within some fixed values. For instance, under these growth conditions, bacteria never travel slower than 0.8 μm/s or faster than 4 μm/s and never switch direction sooner than 4 s after the previous switch.

Effect of growth conditions on the reversal time.

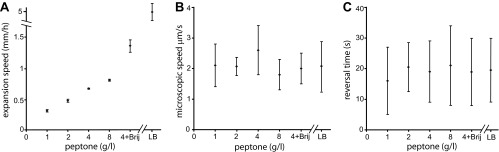

By varying the nutrition level and agar concentration, we showed in our earlier work for morphotype T (14) that the colonial expansion rate is independent of parameters of microscopic motion. Here, for morphotype C, we grew bacteria at various peptone levels (1 g/liter, 2g/liter, 4 g/liter, and 8 g/liter) and in LB while keeping the agar concentration (1% [wt/vol]), the temperature (30°C), and the relative humidity (90%) unchanged. As expected, the expansion rate of the colony increases monotonically with increasing nutrition levels (Fig. 4A). However, the microscopic speed and the reversal time seem to be essentially independent of the nutrition level (Fig. 4B and C), in contrast to morphotype T, for which we observed a dependence of microscopic speed and nutrition level.

Fig 4.

Nutrient dependence. (A) Expansion rate plotted for different nutrient levels, 1 g/liter, 2 g/liter, 4 g/liter, and 8 g/liter peptone, and for LB (rich medium). Data were plotted for the case of 4 g/liter with added Brij 35 (a lower surface tension). Increasing food levels resulted in a faster colonial expansion. The data points represent a constant speed in all cases. Data were collected for a 1% (wt/vol) agar concentration at 30°C and 90% RH. (B and C) Microscopic bacterial speed (B) and reversal time (C) under the same conditions as in panel A. The results show that the microscopic speed and the reversals are largely independent of nutrient levels and that the standard deviation for each condition is larger than the standard deviation between different conditions.

In the next step, we investigated whether the reversal time can be affected by a gradient of nutrients, namely, whether food chemotaxis can affect the reversal time. Colonies were inoculated on agar plates that were kept slightly tilted while the agar was cooling, enabling the colony to sense different food levels in different directions. The colonies spread faster toward the richer (thicker-agar) regions; however, the microscopic motion, namely, the bacterial speed and the reversal times, were not affected.

To further check factors which might affect the motility and reversal time, we tested the effect of surface tension. For this, we have added to the agar, prior to autoclaving, very low concentrations (0.0006% [wt/vol]) of Brij 35, which is a nonionic detergent solution that reduces the surface tension of the medium. At these concentrations, Brij 35 does not affect bacterial metabolism. As seen in Fig. 4, for a constant nutrient level (2 g/liter), colonial expansion was much faster due to lower surface tension. However, the speed and reversal time remained unchanged.

Next, we tested the effect of the surface hardness by varying the agar concentration (0.7 to 1.5% [wt/vol]) while keeping the nutrient level constant (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). On hard (1.3 to 1.4% [wt/vol]) Difco agar, the bacteria grew thick branches, forming multiple layers. Tracking individual cells was limited to the branch tips, and statistics were poor. On Eiken agar, associated with high wettability, the colonies formed monolayers at concentrations of 0.7 to 1.3% (wt/vol). Macroscopic expansion was affected by agar concentration in a nonmonotonic way: fast expansion at intermediate levels of 0.9 to 1.1% (wt/vol) with a maximum at 1.0% (wt/vol) and slow expansion at high (1.2 to 1.3% [wt/vol]) and low (0.7 to 0.8% [wt/vol]) concentrations. The microscopic speed and reversal times were not affected and were similar to those obtained on Difco agar. These results again suggest that the reversal time is a robust parameter, essentially independent of any external factor.

Effect of environmental conditions.

To further explore other possible factors which might affect the reversal time, we have performed four additional experiments in which we changed environmental conditions that affected both the colonial expansion and the motility (temperature, humidity, oxygen concentration, and illumination).

Temperature effect.

We have performed experiments at different temperatures in the range of 25 to 40°C (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). At low temperatures (<28°C), the colony expanded slowly and the microscopic bacterial speed was slow as well. At high temperatures (>37°C), the colony did not expand at all and no microscopic motion was detected; loss of motility was observed at these temperatures in liquid cultures, too, but bacteria were alive. Between 28 and 37°C, the microscopic bacterial speed changed in a nonmonotonic way: fastest motion at 32°C and slowest motion at 28°C and 36°C. In the regimes in which motion was detected (28 to 37°C), the reversal time was not affected.

Humidity effect.

We have changed the humidity between 35 and 90% RH; below 35%, no growth was observed. The drier the air, the slower the colonies expanded and the slower the bacteria moved at the microscopic level (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). For instance, under intermediate dry growth conditions (2 g/liter peptone, 1% [wt/vol] agar, 30°C, and 40% RH), the average colonial expansion rate was 0.5 mm/day (∼20 times slower than that at 90% RH) and the average microscopic speed was 0.5 μm/s (4 times slower than that at 90% RH). But again, the reversal time was not affected, and bacteria changed direction every ∼20 s as observed for all other cases.

Oxygen effect.

We have grown the colonies at high, medium, and low oxygen levels. At very low oxygen levels (plastic bags filled with nitrogen), the expansion rate, the microscopic speed, and the reversal time were not affected (similar to ambient conditions). At very high oxygen levels (plastic bags filled with oxygen), no growth was detected (plates were later placed at ambient conditions for weeks with no recovery; we were not able to recover cells from the colony by reinoculating on fresh LB substrates). At medium oxygen levels (plastic bags filled with a mixture of oxygen and ambient air with no real control of oxygen percentage), the colonies expanded slower and the microscopic motion was slower but the reversal time remained 20 s on average. In other cases, pure oxygen was added at the time of observation only. In these cases, a gradual reduction in each bacterial speed was observed, typically reducing the speeds from ∼2 μm/s to ∼0.5 μm/s, until an abrupt stop. Most cells stopped almost simultaneously after 20 min, and no motion was detected after 30 min. However, the reversal time remained ∼20 s as long as the cells moved.

Illumination effect.

Some phototactic bacteria, such as H. salinarum, show reversals due to gradients of light. Therefore, we tested whether P. dendritiformis C morphotype will react to changes in illumination. Different band pass filters (blue, ∼480 nm; green, ∼508 nm; yellow, ∼560 nm; red, ∼650 nm) were applied successively; the microscope light source (Olympus IX50; standard 30-W halogen light bulb) was turned on and off for different time lengths (between 0.5 s and 1 h), and the motion of the cells was monitored. No changes in bacterial speed or in the reversal time were detected. We have repeated these experiments by illuminating colonies from the side. Side illumination was done at different angles (10°, 20°, and 30° with respect to the surface—this indirectly created a dark-field effect) by using a goose neck fiber optic illuminator (150H; Schölly Fiber Optik GmbH, Germany), creating a gradient in intensity along the xy plane. Illumination intensity at the sample was ∼2 W/cm2. Again, no response to light was detected, suggesting that phototaxis is not a mechanism dictating the reversal events in P. dendritiformis C morphotype bacteria.

Effect of neighboring cells.

We found that cells reversed their direction of motion independently of collisions with neighboring cells. For instance, neighboring cells were tracked to see if they tended to move in the same or opposite directions and whether they tended to switch directions upon contact with cells that were moving in the same or opposite direction. Almost 60% of tracked cells (1,240 cells) were moving in the direction that their close (in-contact) neighbors were moving, indicating hydrodynamic interaction. However, cells were switching direction independently of the direction of motion of their neighbors. Out of 380 tracked cells, 184 (48%) switched direction while close neighbors moved in the opposite direction. Cells that moved in one direction while having 2 neighboring cells, at both sides, moving to the opposite direction showed the same results. This demonstrates that the tendency of switching direction is intrinsic and is independent of hydrodynamics.

Additionally, cells located at the outer part of the branches (having neighbors on one side only) were tracked and found to reverse their direction every 20 s as well. However, they moved slightly slower (10% speed reduction), probably due to a shallower liquid film.

Many one-dimensional head-on collisions, with bacteria moving in opposite directions, were observed, but these incidents did not lead to reversals. Thus, this back-and-forth swarming differs from the reversal behavior of swarming Escherichia coli and other bacteria during collisions. To further verify that collisions did not play a role in direction switching, cells grown on agar were moved into a motility liquid medium by placing a small drop of the motility buffer on the colony, letting bacteria migrate to the drop, and then moving it to a glass slide. In the drop, the bacterial concentration was much smaller; thus, no collisions were observed. However, the cells swam in the drop similarly to what was observed on the agar in that they typically reversed their directions every 20 s. We also observed that cells which were initially grown in standard liquid medium, LB (not transferred from the agar), exhibited an entirely different motion: they swam along nearly straight trajectories with no back-and-forth reversals or run-and-tumble movements. Such cells were monitored for more than 15 min.

Does the C morphotype swarm?

To obtain a better understanding of the motility of the C morphotype on an agar surface and clearly define its motion as “swarming,” we have performed several experiments. First, we have used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to find the motive organelle of P. dendritiformis morphotype C. Possible mechanisms are the S motility of type IV pulling pili, also known as twitching (e.g., A. xylinum or Pseudomonas aeruginosa), a combination of S motility at one pole and an A motility engine that works in the opposite direction (e.g., M. xanthus), a single flagellum that can switch rotational direction from clockwise (CW) to counterclockwise (CCW) (e.g., H. salinarum), and motility due to multiple flagella as often seen in swarming cells (e.g., E. coli). All of these have been previously associated with run-and-tumble or back-and-forth periodic events. Amphitrichous, i.e., two polar flagella, each located at a different pole (e.g., Spirillum), is another potential configuration that bacteria can utilize in back-and-forth reversals.

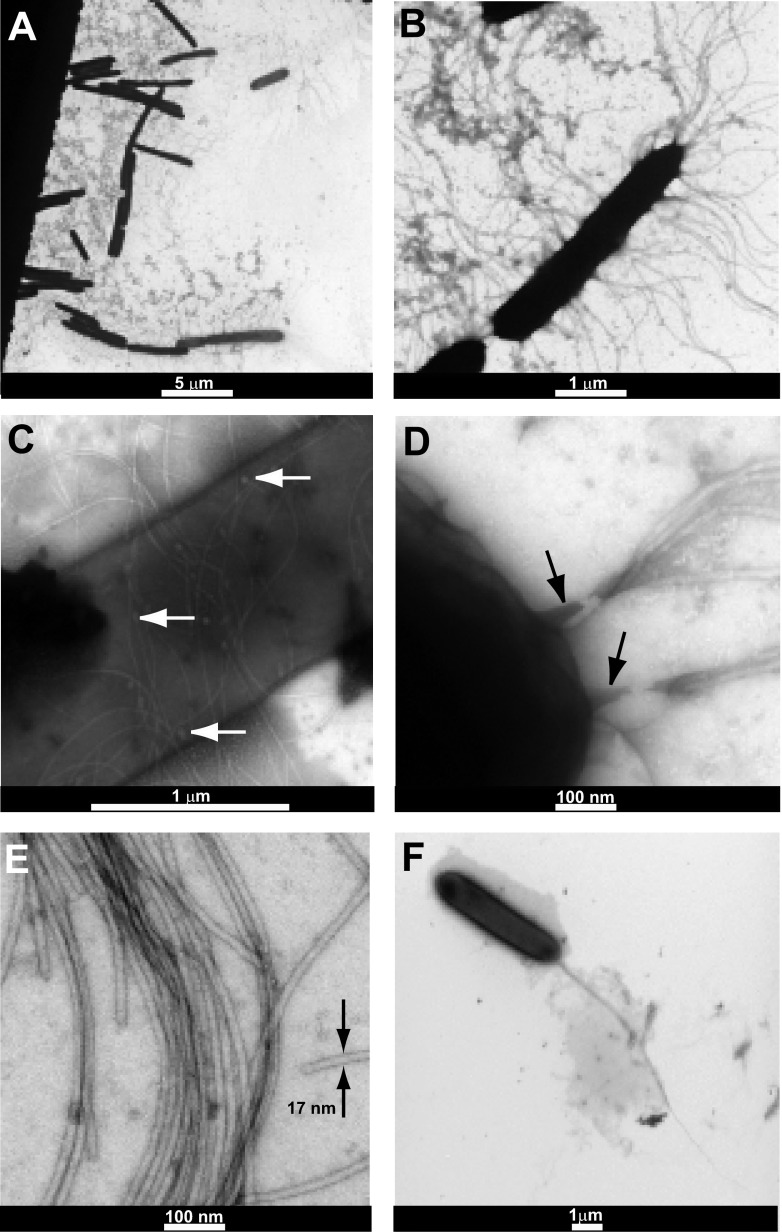

Independent of growth conditions, multiple flagella were observed for cells harvested from agar plates, but bacteria grown on Eiken agar gave better images (the cells are slightly shorter on the Eiken agar). The many flagella (∼100 for each cell) are peritrichous—they are uniformly distributed all over the cell (Fig. 5A and B). A closer look shows that each flagellum is solitarily connected to the membrane through the basal body (Fig. 5C), and in most cases, a few flagella formed bundles (Fig. 5D). Many of these flagellar bundles were found to be distributed in various places around the cell. All of the flagella have similar physical features; they are 10 to 20 μm in length and 17 ± 1 nm in width (Fig. 5E). No pili were observed, suggesting that twitching is not the motility mode of P. dendritiformis morphotype C in these growth conditions. The images were compared to those obtained for cells grown in liquid medium, in which a single bundle of 4 flagella, located at one pole, was observed (Fig. 5F). This suggests that extracellular conditions had a very large influence on the number and position of flagella on the cells.

Fig 5.

TEM images of P. dendritiformis morphotype C bacteria. (A and B) Low (A) and high (B) magnifications of cells harvested from Eiken agar plates expose peritrichous flagella; they are uniformly distributed over the cell. Cells grown on Difco agar look similar, but the image quality is poorer due to harvesting problems. (C and D) A closer look at cells harvested from Eiken agar plates shows the basal bodies (marked with white arrows in panel C); each flagellum is solitarily connected to the membrane through the basal body. In most cases, groups of few flagella form bundles (the base of the bundle is marked with a black arrow in panel D), so that many flagellar bundles are distributed all over the cell as seen in panel B. (E) All flagella look similar; they are 10 to 20 μm in length and 17 nm in width. (F) Cells grown in LB liquid medium exhibit a single bundle made of 4 flagella, located at one pole.

Second, we have used standard flagellar shearing protocols to shear flagella off the cells. As described above, bacteria were collected from agar plates by placing a small drop of the motility buffer on the colony, allowing bacteria to migrate to the drop. Cells that were not sheared moved back and forth in the liquid, indicating that their motion on the agar was flagellum driven. Shearing was achieved by repeated pipetting through a narrow (0.6-mm-diameter) straw. Sheared cells did not swim in the liquid bulk, and flagella were not observed in TEM. Third, a suspension of sheared bacteria was placed on an untreated standard glass slide. After bacteria attached to the surface, they started to rotate either CW or CCW. Independent of whether they rotated CW or CCW, they reversed their direction every few seconds, indicating that the flagellar rotors are still present and active (see Movie S3 in the supplemental material).

All three results together strongly suggest that flagella are the motive organelles in the C morphotype and that the spreading of the C morphotype fulfills the more-stringent definition of swarming as a flagellum-driven motility on surfaces (1) (the less-stringent definition of swarming is any type of collective bacterial motion, even if not powered by flagella).

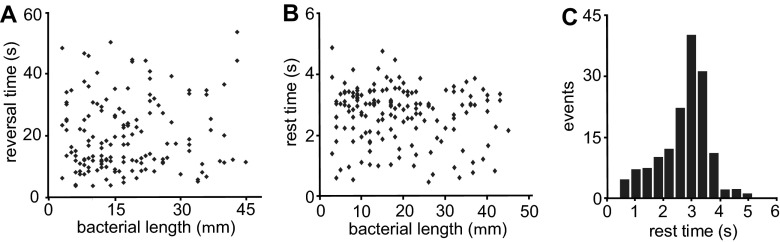

Effect of bacterial length.

Our results that the reversal time is essentially independent of all parameters tested point toward the existence of a robust internal clock for the timing of reversal events. It is very likely that the flagella need to be synchronized to reverse the direction. The way flagella are structured on the cells raises the possibility that, similarly to other peritrichous flagellated species, large bundles are formed at the poles during motion. For a reversal event to happen, the signal has to travel through the cell from one pole to the other, turning on and off the rotation of the flagellar bundles or switching their direction. If the signal propagation is the limiting factor for the speed of reversals, one expects a significant rest time when bacteria change their direction and that this rest time depends on the length of the bacteria. However, Fig. 6 shows that the reversal time (Fig. 6A) and the rest time (Fig. 6B) are independent of bacterial length (P values of 0.076 and 0.068, respectively). The histogram of rest times (Fig. 6C) is strongly asymmetric, with a maximum around 3 s, many shorter events, and a minimum rest time of approximately 0.4 s. Also, the minimum rest time seems to be independent of the bacterial length, as suggested by Fig. 6B, which points toward another origin. Similar rest times have been described for B. subtilis (29) and attributed to flagellar bundle kinetics.

Fig 6.

Effect of bacterial length. (A) Reversal time as a function of bacterial length (2 g/liter peptone, 1% [wt/vol] Difco agar, 30°C, and 90% RH). No correlation was observed. (B) Rest time as a function of bacterial length (same growth conditions). No correlation was observed. (C) Probability of rest time.

DISCUSSION

Hydrodynamic interaction has been considered the key player in many cases of collective motion observed in a number of bacterial species. However, it has been recently suggested that short-range steric interactions might dominate over hydrodynamic interaction in swarming bacteria. For elongated, rigid, self-propelled particles, collisions (i.e., short-range steric interactions) seem to result in the alignment of motion that leads to a particular length and time correlation and to the formation of the classical swarming patterns of whirls and jets (2, 3). It is expected that geometrical factors of cell structure, such as the aspect ratio (length/width), are important for the type of collective motion. The pioneering work on P. dendritiformis (47, 59, 60) has shown that morphotype C colonies exhibit chiral morphology with twisted branches as a combined result of flagellar chirality and cell-cell orientation interactions. The theoretical models showed that the length of these motile bacteria plays a major role in the resultant pattern which limits the average rotation, reducing the chance to form whirls and jets.

Wensink et al. (45) have recently calculated a non-equilibrium-phase diagram for various aspect ratios and volume fractions of self-propelled rods (bacteria), taking into account only steric interaction between the rods; hydrodynamic interaction was neglected. For very long (rigid) rods (aspect ratio of >13) and at sufficiently high-volume fractions (>0.3), they found that “bacteria” tend to assemble in homogeneous long lanes corresponding to quasismectic regions of polar order. Our results are in agreement with this prediction.

Besides being assembled in homogeneous long lanes, we found that all cells show periodic reversals with a reversal time that was robust under all conditions tested. This phenomenon was not included in recent models (45). Periodic reversals have been observed experimentally in other species, too, but their mechanism, properties, or function seems to be different. Starting with peritrichously flagellated bacteria, it was recently shown that CW flagellar rotation in swarming E. coli cells results in reversal events (21). These reversals are different from the run-and-tumble events of swimming bacteria and were found only in a small fraction at the edges of the colonies. The distribution of reversal times was approximately exponential, corresponding to a constant probability of changing direction, in contrast to the distribution of reversal times observed here. Instead of an exponential decay, we found a broad distribution and a clear maximum at about 12 s, indicating that the mechanism that drives the reversals might be different.

Reversals were also observed in B. subtilis. Cisneros et al. (61) observed reversals of cells in liquid medium (swimming cells) upon collisions with obstacles, indicating some mechanical sensing. One suggested function of these reversals is that the cells try to avoid jammed areas. As discussed earlier, reversals in the P. dendritiformis C morphotype seem to be spontaneous and independent of any mechanical interaction with neighboring cells or any other object.

Reversals found in the archaeon H. salinarum (53, 54), which grows in high-salt environments, are a behavioral response to gradients of light or oxygen (phototaxis or aerotaxis, respectively). No response to food or light gradients was found for the P. dendritiformis C morphotype. Finally, reversals were found in pilus-driven species. For example, A. xylinum bacteria (55) are known for prolific synthesis of cellulose, in which the motion is pilus driven and the microscopic back-and-forth motion is achieved by attachment to the extruded cellulose ribbon produced. In M. xanthus (48–52), the cell movement is propelled by a polar S engine (pulling type IV pili) at the leading end of the cell and by an A gliding engine that generates motion in the opposite direction. Measurements of the expansion rates of M. xanthus mutants have revealed that the reversal period of wild-type strains is optimized for fast expansion. It was suggested that the back-and-forth motion in this case increases the local alignment of cells and reduces the interference between cellular motions. M. xanthus moves much slower, switches direction at a much lower rate, and uses a different motive organelle than the P. dendritiformis C morphotype; however, it is still possible that the reversals fulfill a similar function in P. dendritiformis.

To reverse the direction of motion, flagella at different locations along the cell body need to be synchronized, which requires a signal to travel along the cell body. The speed of the signal and the body length should set a minimum rest time during reversals. Surprisingly, we observed no dependence of the minimal rest time (0.35 s) on body length, a finding which indicates that signaling along the cell body is not the limiting factor for flagellar synchronization. Assuming a rest time of 0.50 s and a cell length of 40 μm, we can calculate the lower bound for the speed of the signal to be approximately 60 μm/s. This speed seems to be too fast even for fast calcium waves (62), and it remains unclear how periodic reversals are orchestrated.

P. dendritiformis has two motile morphotypes, the C morphotype discussed here and the T morphotype, which is a shorter (aspect ratio, ∼5), rod-shaped, motile strain that swarms in whirls and jets (14). Both have the same 16S rRNA. Colonies of either morphotype, grown from a single cell, are likely to exhibit spontaneous transitions in which small regions of a colony might grow branches containing cells of the other morphotype. When this happens, the dynamics of swarming of the bacteria at the transitioned regions is changed as well (see arrow in Fig. 1E). Our experiments suggest that the dramatic change in aspect ratio, a result of the spontaneous morphological transition, might be correlated with the different type of collective motion. By now, it is known that one major difference between morphotypes T and C is a topological defect in cell division which makes C much longer. However, the study of the differences between the two morphotypes is not completed, and concrete conclusions about the role of aspect ratio in changing the swarming pattern must be postponed. Patrick et al. (63) showed that topological defects (ΔminJ) in cell division (i.e., the formation of longer cells) create swarming motility defects in B. subtilis. The long hyperflagellated and surfactant producer cells form spiraling whorls on the surface of the medium instead of the classic spreading pattern formed by the wild type.

To conclude, we have found the periodic reversals to be independent of environmental conditions such as initial nutrient level, agar rigidity, surfactant addition, humidity level, temperature, nutrient chemotaxis, oxygen level, illumination intensity, and gradient and additionally independent of cell length and cell density (collisions with other cells). Together with the fact that the reversal periodicity is also not correlated with the colony expansion (in contrast to other bacteria), the evolutionary advantage of this unique back-and-forth swarming remains a mystery.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Inna Brainis for providing the bacterial strain and the growth protocol. We are grateful to Rasika M. Harshey, Harry L. Swinney, and Shelley M. Payne for many useful discussions and guidance.

E.B.-J. acknowledges support from the Tauber Family Funds and the Maguy-Glass Chair in Physics of Complex Systems at Tel Aviv University and partial support from NSF grant PHY-0822283 and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) at Rice University. E.-L.F. acknowledges support from the Robert A. Welch Foundation under grant F-1573.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 April 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00080-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Harshey RM. 2003. Bacterial motility on a surface: many ways to a common goal. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:249–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang HP, Be'er A, Florin E-L, Swinney HL. 2010. Collective motion and density fluctuations in bacterial colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:13626–13630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang HP, Be'er A, Smith RS, Florin E-L, Swinney HL. 2010. Swarming dynamics in bacterial colonies. Europhys. Lett. 87:48011. 10.1209/0295-5075/87/48011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kearns DB. 2010. A field guide to bacterial swarming motility. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:634–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Butler MT, Wang Q, Harshey RM. 2010. Cell density and mobility protect swarming bacteria against antibiotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:3776–3781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsuyama T, Kaneda K, Nakagawa Y, Isa K, Hara-Hotta H, Yano I. 1992. A novel extracellular cyclic lipopeptide which promotes flagellum-dependent and -independent spreading growth of Serratia marcescens. J. Bacteriol. 174:1769–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harshey RM, Matsuyama T. 1994. Dimorphic transition in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: surface-induced differentiation into hyperflagellate swarmer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:8631–8635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu Y, Hosua BG, Berg HC. 2011. Microbubbles reveal chiral fluid flows in bacterial swarms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:4147–4151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kearns DB, Losick R. 2003. Swarming motility in undomesticated Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 49:581–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Q, Frye JG, McClelland M, Harshey RM. 2004. Gene expression patterns during swarming in Salmonella typhimurium: genes specific to surface growth and putative new motility and pathogenicity genes. Mol. Microbiol. 52:169–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daniels R, Reynaert S, Hoekstra H, Verreth C, Janssens J, Braeken K, Fauvart M, Beullens S, Heusdens C, Lambrichts I, De Vos DE, Vanderleyden J, Vermant J, Michiels J. 2006. Quorum signal molecules as biosurfactants affecting swarming in Rhizobium etli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:14965–14970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ben-Jacob E, Becker I, Shapira Y, Levine H. 2004. Bacterial linguistic communication and social intelligence. Trends Microbiol. 12:366–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ben-Jacob E, Cohen I, Gutnick DL. 1998. Cooperative organization of bacterial colonies: from genotype to morphotype. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:779–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Be'er A, Smith RS, Zhang HP, Florin E-L, Payne SM, Swinney HL. 2009. Paenibacillus dendritiformis bacterial colony growth depends on surfactant but not on bacterial motion. J. Bacteriol. 191:5758–5764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ingham CJ, Ben-Jacob E. 2008. Swarming and complex pattern formation in Paenibacillus vortex studied by imaging and tracking cells. BMC Microbiol. 8:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Henrichsen J. 1972. Bacterial surface translocation: a survey and a classification. Bacteriol. Rev. 36:478–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Copeland MF, Weibel DB. 2009. Bacterial swarming: a model system for studying dynamic self-assembly. Soft Matter 5:1174–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim W, Killam T, Surette MG. 2003. Swarm-cell differentiation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium results in elevated resistance to multiple antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 185:3111–3117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lai S, Tremblay J, Deziel E. 2009. Swarming motility: a multicellular behaviour conferring antimicrobial resistance. Environ. Microbiol. 11:126–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ben-Jacob E. 2003. Bacterial self-organization: co-enhancement of complexification and adaptability in a dynamic environment. Philos. Transact. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 361:1283–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Turner L, Zhang R, Darnton NC, Berg HC. 2010. Visualization of flagella during bacterial swarming. J. Bacteriol. 192:3259–3267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang R, Turner L, Berg HC. 2010. The upper surface of an Escherichia coli swarm is stationary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:288–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Darnton NC, Turner L, Rojevsky S, Berg HC. 2010. Dynamics of bacterial swarming. Biophys. J. 98:2082–2090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sokolov A, Aranson IS. 2009. Reduction of viscosity in suspension of swimming bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103:148101. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.148101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dombrowski C, Cisneros L, Chatkaew S, Goldstein RE, Kessler JO. 2004. Self-concentration and large-scale coherence in bacterial dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93:098103. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.098103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sokolov A, Aranson IS, Kessler JO, Goldstein RE. 2007. Concentration dependence of the collective dynamics of swimming bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98:158102. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.158102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tuval I, Cisneros L, Dombrowsky C, Wolgemuth CW, Kessler JO, Goldstein RE. 2005. Bacterial swimming and oxygen transport near contact lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:2277–2282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cisneros LH, Cortez R, Dombrowski C, Goldstein RE, Kessler JO. 2007. Fluid dynamics of self-propelled microorganisms, from individuals to concentrated populations. Exp. Fluids 43:737–753 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cisneros LH, Kessler JO, Ganguly S, Goldstein RE. 2011. Dynamics of swimming bacteria: transition to directional order at high concentration. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 83:061907. 10.1103/PhysRevE.83.061907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Be'er A, Harshey RM. 2011. Collective motion of surfactant-producing bacteria imparts superdiffusivity to their upper surface. Biophys. J. 101:1017–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sokolov A, Apodaca MM, Grzybowski BA, Aranson IS. 2010. Swimming bacteria power microscopic gears. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:969–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Narayan V, Ramaswamy S, Menon N. 2007. Long-lived giant number fluctuations in a swarming granular nematic. Science 317:105–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aranson IS, Snezhko A, Olafsen JS, Urbach JS. 2008. Comment on “long-lived giant number fluctuations in a swarming granular nematic.” Science 320:612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Parrish JK, Edelstein-Keshet L. 1999. Complexity, pattern, and evolutionary trade-offs in animal aggregation. Science 284:99–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Makris NC, Ratilal P, Jagannathan S, Gong Z, Andrews M, Bertsatos I, Godø OR, Nero RW, Jech JM. 2009. Critical population density triggers rapid formation of vast oceanic fish shoals. Science 323:1734–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ballerini M, Cabibbo N, Candelier R, Cavagna A, Cisbani E, Giardina I, Lecomte V, Orlandi A, Parisi G, Procaccini A, Viale M, Zdravkovic V. 2008. Interaction ruling animal collective behavior depends on topological rather than metric distance: evidence from a field study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:1232–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nathan R, Getz WM, Revilla E, Holyoak M, Kadmon R, Saltz D, Smouse PE. 2008. A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:19052–19059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aranson IS, Sokolov A, Kessler JO, Goldstein RE. 2007. Model for dynamical coherence in thin films of self-propelled microorganisms. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 75:040901. 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.040901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simha RA, Ramaswamy S. 2002. Hydrodynamic fluctuations and instabilities in ordered suspensions of self-propelled particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89:058101. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.058101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramaswamy S, Simha RA, Toner J. 2003. Active nematics on a substrate: giant number fluctuations and long-time tails. Europhys. Lett. 62:196–202 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Toner J, Tu YH, Ramaswamy S. 2005. Hydrodynamics and phases of flocks. Ann. Phys. (N. Y.) 318:170–244 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dreschera K, Dunkela J, Cisneros LH, Gangulya S, Goldstein RE. 2011. Fluid dynamics and noise in bacterial cell-cell and cell-surface scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:10940–10945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gyrya V, Aranson IS, Berlyand LV, Karpeev D. 2010. A model of hydrodynamic interaction between swimming bacteria. Bull. Math. Biol. 72:148–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Peruani F, Deutsch A, Bar M. 2006. Nonequilibrium clustering of self-propelled rods. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 74:030904. 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.030904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wensink HH, Dunkel J, Heidenreich S, Drescher K, Goldstein RE, Löwen H, Yeomans JM. 2012. Meso-scale turbulence in living fluids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:14308–14313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tuson HH, Copeland MF, Carey S, Sacotte R, Weibel DB. 2013. Flagella density regulates Proteus mirabilis swarm cell motility in viscous environments. J. Bacteriol. 195:368–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ben-Jacob E, Cohen I, Shochet O, Tenenbaum A, Czirok A, Vicsek T. 1995. Cooperative formation of chiral patterns during growth of bacterial colonies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75:2899–2902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu Y, Kaiser AD, Jiang Y, Alber SA. 2009. Periodic reversal of direction allows Myxobacteria to swarm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:1222–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yu R, Kaiser D. 2007. Gliding motility and polarized slime secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 63:454–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blackhart BD, Zusman DR. 1985. “Frizzy” genes of Myxococcus xanthus are involved in control of frequency of reversal of gliding motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82:8767–8770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Igoshin OA, Welch R, Kaiser D, Oster G. 2004. Waves and aggregation patterns in myxobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:4256–4261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mauriello EMF, Mignot T, Yang Z, Zusman DR. 2010. Gliding motility revisited: how do the myxobacteria move without flagella? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74:229–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Krohs U. 1995. Damped oscillations in photosensory transduction of Halobacterium salinarium induced by repellent light stimuli. J. Bacteriol. 177:3067–3070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lindbeck JC, Goulbourne EA, Jr, Johnson MS, Taylor BL. 1995. Aerotaxis in Halobacterium salinarium is methylation-dependent. Microbiology 141:2945–2953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kondo T, Nojiri M, Hishikawa Y, Togawa E, Romanovicz D, Brown RM., Jr 2002. Biodirected epitaxial nanodeposition of polymers on oriented macromolecular templates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:14008–14013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sirota-Madi A, Olender T, Helman Y, Brainis I, Finkelshtein A, Roth D, Hagai E, Leshkowitz D, Brodsky L, Galatenko V, Nikolaev V, Gutnick DL, Lancet D, Ben-Jacob E. 2012. Genome sequence of the pattern-forming social bacterium Paenibacillus dendritiformis C454 chiral morphotype. J. Bacteriol. 194:2127–2128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sokolov A, Aranson IS. 2012. Physical properties of collective motion in suspensions of bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109:248109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Be'er A, Zhang HP, Florin E-L, Payne SM, Ben-Jacob E, Swinney HL. 2009. Deadly competition between sibling bacterial colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:428–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cohen I, Ben-Jacob E. 2000. Orientation field model for chiral branching growth of bacterial colonies. http://arxiv.org/pdf/cond-mat/0008446v1.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60. Ben-Jacob E, Cohen I, Golding I, Kozlovsky Y. 2001. Modeling branching and chiral colonial patterning of lubricating bacteria, p 211–253 In Maini PK, et al. (ed), Mathematical models for biological pattern formation. Springer Science+Business Media, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cisneros L, Dombrowski C, Goldstein RE, Kessler JO. 2006. Reversal of bacterial locomotion at an obstacle. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 73:030901. 10.1103/PhysRevE.73.030901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jaffe LF. 2010. Fast calcium waves. Cell Calcium 48:102–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Patrick JE, Kearns DB. 2008. MinJ (YvjD) is a topological determinant of cell division in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 70:1166–1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.