Abstract

Mucormycosis is a life-threatening fungal infection almost uniformly affecting diabetics in ketoacidosis or other forms of acidosis and/or immunocompromised patients. Inhalation of Mucorales spores provides the most common natural route of entry into the host. In this study, we developed an intratracheal instillation model of pulmonary mucormycosis that hematogenously disseminates into other organs using diabetic ketoacidotic (DKA) or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice. Various degrees of lethality were achieved for the DKA or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice when infected with different clinical isolates of Mucorales. In both DKA and cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate models, liposomal amphotericin B (LAmB) or posaconazole (POS) treatments were effective in improving survival, reducing lungs and brain fungal burdens, and histologically resolving the infection compared with placebo. These models can be used to study mechanisms of infection, develop immunotherapeutic strategies, and evaluate drug efficacies against life-threatening Mucorales infections.

INTRODUCTION

Mucormycoses are uncommon life-threatening fungal infections caused by fungi of the order Mucorales (1–3). These infections almost uniformly afflict the immunocompromised hosts, those with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or other forms of acidosis, and trauma patients (e.g., victims of the recent natural disasters of the Joplin tornado [4] and the Indian tsunami [5]) (6, 7). Due to the rising prevalence of diabetes, cancer, and organ transplantation in aging populations, as well as the recent increase in natural disasters, the number of patients at risk for this deadly infection is significantly rising and is expected to continue to rise (8–10).

Fungi belonging to the order Mucorales are distributed into six families, all of which can cause cutaneous and hematogenously disseminated infections (1, 6). Species belonging to the family Mucoraceae are isolated more frequently from patients with mucormycosis than any other family. Among the Mucoraceae, Rhizopus spp. are the most common cause of mucormycosis and are responsible for approximately 70% of all infections and 90% of rhinocerebral cases (6, 11, 12). However, recently more cases caused by the previously less frequent species of Lichtheimia (formerly Absidia) corymbifera, Apophysomyces elegans, and Mucor species have been reported (4, 6, 13–17). Increasing numbers of cases of mucormycosis have been also reported due to infection with Cunninghamella spp. (18–20).

Despite disfiguring surgical debridement and adjunctive antifungal therapy, the overall mortality of mucormycosis remains approximately 50%. In the absence of surgical removal of the infected focus, antifungal therapy alone is rarely curative, resulting in a 100% mortality rate for patients with hematogenously disseminated disease (1, 9, 21–24). Clearly, new strategies to prevent and treat mucormycosis are urgently needed. Because of the rarity of the disease, controlled clinical trials are hard to conduct. Consequently, relevant animal models of mucormycosis represent a suitable alternative to provide well-controlled comparative analyses of antifungal therapies.

Several murine models have been developed to study mucormycosis in vivo, including intravenous (25–27), intranasal (28, 29), and intrasinus (30) infections using diabetic mice. Additionally, neutropenic (26, 31, 32), corticosteroid-treated (33), and deferoxamine-treated mouse models (34), as well as a deferoxamine-treated guinea pig model (35, 36), have been described. Even immunocompetent mice have been utilized to study activity of antifungal drugs (37). A variety of Mucorales have been utilized in these models, including Rhizopus oryzae, Rhizopus microsporus, and Mucor and Lichtheimia spp. There is no clear advantage to any one of these models in evaluating the efficacy of different antifungal regimens, and none of the models completely accurately recapitulates the most common normal route of infection (i.e., inhalation).

We have developed a pulmonary murine model of mucormycosis using DKA or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice via inoculation of Mucorales through the intratracheal (IT) route. We utilized this model to evaluate the efficacy of liposomal amphotericin B (LAmB) and posaconazole (POS) in treating the infection since these two drugs are currently among the most used agents to treat the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and culture conditions.

Several clinical Mucorales isolates were used in this study. Rhizopus oryzae 99-880 was isolated from a brain abscess, while R. oryzae 99-892 and R. microsporus 99-1150 were isolated from patients with lung infections. These three isolates were obtained from the Fungus Testing Laboratory, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX. Cunninghamella bertholletiae 182 is also a clinical isolate and was a gift from Thomas Walsh (Cornell University). Lichtheimia corymbifera and Rhizomucor are also clinical isolates obtained from the DEFEAT Mucor clinical study (38). Apophysomyces elegans ATCC 90757 and Mucor circinelloides ATCC 1216b were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Mucorales isolates were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA; BD Biosciences—Diagnostic Systems) plates for 3 to 5 days at 37°C. The sporangiospores were collected in endotoxin-free Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.01% Tween 80, washed with PBS, and then counted with a hemocytometer to prepare the final inocula.

MIC test.

The broth microdilution method was performed according to the Clinical Laboratory and Standards Institute (CLSI) M38-A2 method approved for filamentous fungi. LAmB (Astellas/Gilead) was dissolved initially in sterile water to yield 4 mg/ml. POS (Merck & Co., Inc.) was purchased as an oral suspension (200 mg/5 ml) and kept at room temperature. Stock solutions were diluted in RPMI 1640 medium buffered to pH 7.0 with morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) and dispensed into 96-well plates. The inoculated 96-well plates were incubated at 37°C and read at 24 h with the MIC endpoint defined as the lowest concentration that causes 90 to 100% growth inhibition relative to the drug-free growth control (64). The minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) was determined by spotting samples from all of the 96-well plates on PDA plates supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubating at 37°C for 2 days. The MFC was defined as the least concentration of the drug at which the organism failed to grow on the PDA plate.

Animal model.

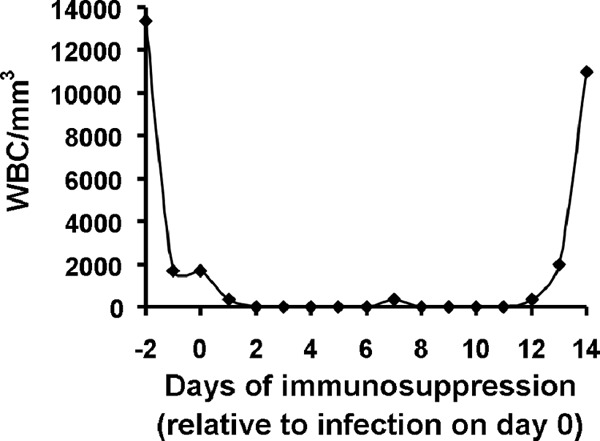

Male ICR (Institute for Cancer Research) mice (6 to 8 weeks old and weighing 20 to 25 g) were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY) and were housed in groups of five mice each. They were given irradiated feed and sterile water containing 50 μg/ml Baytril (Bayer) ad libitum. Mice were rendered diabetic by administration of streptozotocin (210 mg/kg of body weight by intraperitoneal [i.p.] injection) as described previously (25, 26, 39). This dose of streptozotocin caused diabetes in 80 to 90% of the injected mice. Glycosuria and ketonuria were determined with keto-Diastix reagent strips (Bayer, Elkhart, IN) 7 days after streptozotocin treatment. Only mice that developed diabetes with mild ketoacidosis (DKA) (level of ketonuria, ≤5 mg/dl) were included in the study. For DKA mice, a dose of cortisone acetate (250 mg/kg) was also administered subcutaneously (SQ) on days −2 and +3 relative to infection. For the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate model, mice were immunosuppressed with cyclophosphamide (200 mg/kg administered i.p.) and cortisone acetate (500 mg/kg administered SQ) on days −2, +3, and +8 relative to infection. This treatment regimen results in ∼16 days of leukopenia, with total white blood cell count dropping from ∼13,000/cm3 to almost no detectable leukocytes as determined by a Unopette system (Becton-Dickinson and Co.) (Fig. 1). IT injection of the clinical isolate spores was carried out by the method modified from Zou and coworkers (40, 41). Briefly, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of 0.2 ml of a mixture of ketamine at 82.5 mg/kg (Phoenix, St. Joseph, MO) and xylazine at 6 mg/kg (Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, IA). The sedated mice were kept on heat pads (Fisher Scientific) which were prewarmed to 37°C. While pulling the tongue anteriorly to the side with forceps, 25 μl of fungal spores (2.5 × 105 cells) in PBS was injected through the vocal cords into the trachea with a Fisherbrand gel-loading tip (catalog number 02-707-138). This technique resulted in <1.0% injury to the vocal cords of the mice. A pilot dose-ranging study suggested that this inoculum was the optimal inoculum to induce 100% mortality in both DKA and cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate murine models (Fig. 2). To confirm the inoculum delivered to the lungs, two or three mice were sacrificed immediately after the infection, and lungs were dissected, homogenized, and quantitatively cultured on PDA plates plus 0.1% Triton. CFU were enumerated after incubation at 37°C for 24 h. After infection, the mice were randomly sorted into different treatment groups. For uninfected control mice, 25 μl of PBS alone was intratracheally injected.

Fig 1.

Duration of leukopenia induced by three doses of cyclophosphamide and cortisone acetate. Data are shown as mean leukocyte counts from three mice for each time point. Cyclophosphamide (200 mg/kg) and cortisone acetate (500 mg/kg) were given on days −2, +3, and + 8. WBC, white blood cells.

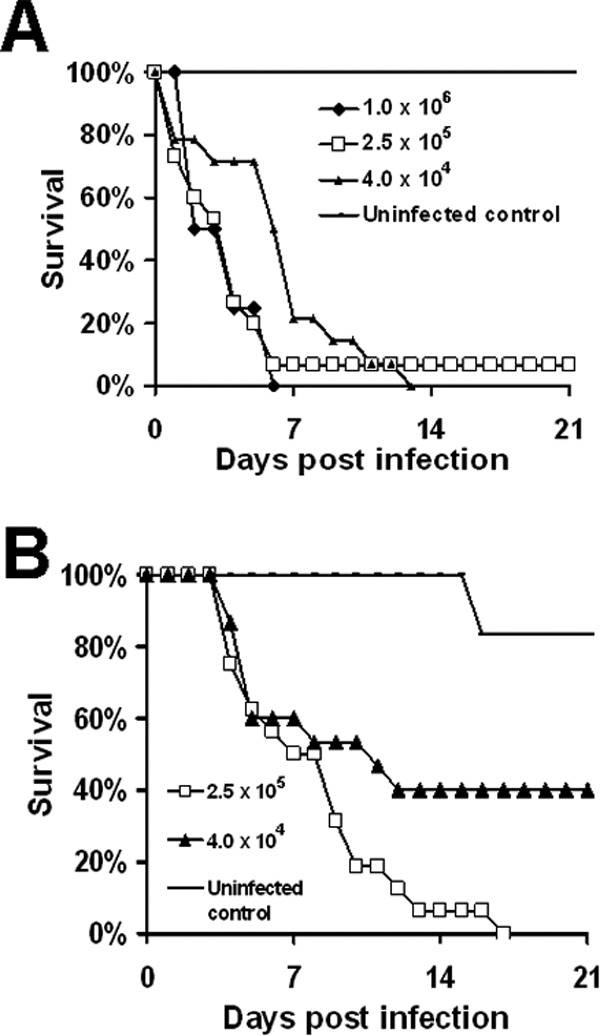

Fig 2.

Development of pulmonary mucormycosis infection models through intratracheal injection. Survival of DKA mice (n = 12 for 1 × 106, 15 for 2.5 × 105, 14 for 4.0 × 104, and 6 for uninfected control) (A) or cyclophosphamide/cortisone acetate-treated mice (n = 16 mice for 2.5 × 105, 15 mice for 4.0 × 104, and 6 mice for uninfected control from two independent experiments with similar results) (B) infected with different inocula of R. oryzae strain 99-880.

Antifungal therapy.

LAmB (4 mg/ml solution in sterile water) was diluted daily in 5% endotoxin-free dextrose and given intravenously via tail vein injection at a dose of 15 mg/kg/day using a 29-guage, 0.5-inch needle (Kendall Monoject). POS oral suspension was given by oral gavage at a total dose of 60 mg/kg/day or 30 mg/kg twice daily (b.i.d.). Infected untreated control mice (placebo) received 5% dextrose water. The primary endpoint for efficacy was time to morbidity of infected mice. Tissue fungal burden and histopathological examination of target tissues served as secondary endpoints. For survival studies, therapy was initiated 16 h after infection and continued until day +7 relative to infection. For tissue fungal burden and histopathological examination, treatment continued until day +3 relative to infection, after which lungs and brains (primary and secondary target organs) were removed from surviving mice, and the tissue fungal burden was determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using a modification of our published method (42). Briefly, brains and lungs were collected and homogenized in Whirl Pak bags (Fisher Scientific). Approximately 1.5 ml of the homogenate was transferred to sterile screw-cap lysing matrix tubes with 1.4-mm-diameter glass beads (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). The homogenate containing mouse tissues and fungal hyphae was mechanically disrupted using Fastprep FP120 (Bio 101 Thermo Electro Corporation) with three bursts of 30 s at speed 4 (with incubation on ice between bursts). The supernatant was collected from the secondary homogenate by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min at 4°C. DNA was extracted from secondary homogenate with the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was recovered in 200 μl of elution buffer and stored at −20°C until analysis by qPCR.

Oligonucleotide amplification primers of the R. oryzae 18S rRNA gene (GenBank accession no. AF113440) were designed with Primer Express software (version 1.5; Applied Biosystems) and synthesized commercially (Sigma-Aldrich). The sequences of these oligonucleotides are as follows: (i) sense amplification primer, 5′-GCGGATCGCATGGCC-3′; and (ii) antisense amplification primer, 5′-CCATGATAGGGCAGAAAATCG-3′. The qPCRs were performed as described previously (42, 43). Five point standard curves were prepared by spiking uninfected lungs or brains with known concentrations of R. oryzae sporangiospores (102 to 106), extracting total lung or brain DNA, and then analyzing R. oryzae-specific nucleic acid concentrations by real-time qPCR. The standard curve created by spiking spores was used to calculate log10 spore equivalents per gram of tissue.

For histopathological analysis, lungs and brain samples were collected from the same organs processed for CFU and fixed in 10% zinc formalin. Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain or hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain for light microscopy examination.

Bioassay.

Serum concentrations of POS were measured in uninfected DKA or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice following 6 days of POS at 30 mg/kg b.i.d. or 60 mg/kg/day (serum was collected 4 h after administration of the last dose). POS concentrations were measured by bioassay as was previously described (44). Briefly, 100 μl of serum was instilled in duplicate into wells cored into PDA plates that had been inoculated with 1 × 104 cells/ml of Candida kefyr ATCC 66028. After 48 h of incubation, zones of inhibition were measured, and POS concentrations were interpolated from a standard curve.

Statistical analysis.

The nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was utilized to compare tissue fungal burden. The nonparametric log rank test was utilized to determine differences in survival time. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. In view of multiple tests conducted in comparing the virulence of different Mucorales isolates, P values of <0.01 were considered to declare statistical significance to control for an overall type I error rate of 0.05.

All procedures involving mice were approved by the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute Animal Care and Use Committee, following the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal housing and care. The institute has a U.S. Public Health Service-approved animal welfare assurance.

RESULTS

All tested Mucorales isolates are susceptible to LAmB and POS in vitro.

The results for the in vitro activity of LAmB and POS against 8 isolates of Mucorales are presented in Table 1. LAmB and POS were active against Mucorales, with MIC values ranging from 0.19 to 0.39 μg/ml for LAmB and 0.19 to 0.78 μg/ml for POS. The only exception is the low activity of LAmB against C. bertholletiae, which had an MIC of 6.25 μg/ml. It was also noted that although POS activity inhibited R. oryzae 99-880 growth (i.e., MIC = 0.78 μg/ml), the minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) was 25 μg/ml.

Table 1.

Susceptibilities of different Mucorales isolates to LAmB or POS in vitro

| Organism | LAmB |

POS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (μg/ml) | MFC (μg/ml) | MIC (μg/ml) | MFC (μg/ml) | |

| R. oryzae 99-880 | 0.39 | 1.56 | 0.78 | 25 |

| R. oryzae 99-892 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 0.39 | 0.78 |

| R. microsporus | 0.19 | 1.56 | 0.19 | 0.78 |

| Rhizomucor | 0.19 | 1.56 | 0.39 | 0.78 |

| Apophysomyces | 0.19 | 0.78 | 0.19 | 0.78 |

| C. bertholletiae 182 | 6.25 | 50 | 0.19 | 0.78 |

| M. circinelloides | 0.19 | 1.56 | 0.39 | 1.56 |

| L. corymbifera | 0.19 | 1.56 | 0.19 | 0.78 |

Development of a Mucorales pulmonary infection model through intratracheal injection.

We wanted to develop a mouse model of infection that better recapitulated the natural route of infection (inhalation) of the majority of mucormycosis cases. In pilot studies, we compared intranasal versus IT route of inoculation. We found that IT inoculation of 2.5 × 105 spores consistently delivered higher inoculation to the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mouse lungs (median, 1.8 × 103 [25th quartile and 75th quartile, 9.5 × 102 and 1.3 × 103]) that resulted in ∼100% mortality compared to the intranasal model (400 [125, 263]), which resulted in no death of mice. We also tried inducing pulmonary infection using the inhalational model we previously developed for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (45), but infection could not be induced, possibly due to the larger size of R. oryzae spores than Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. Consequently, we determined the virulence of R. oryzae 99-880 in DKA or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice infected with different inocula via IT injection. This strain was chosen because (i) it is the only Mucorales with a published genome sequence (46), (ii) it has been used extensively in virulence and drug efficacy studies (25, 26, 31, 47, 48), (iii) it is susceptible to both LAmB and POS in vitro (Table 1), and (iv) R. oryzae is the major cause of mucormycosis (3, 6). As shown in Fig. 2, lethal infection was established in an inoculum-dependent manner. For example, DKA mouse inocula of Rhizopus oryzae 99-880 at 1 × 106, 2.5 × 105, and 4 × 104 cells resulted in almost complete mortality, with a median survival time of 3, 4, and 6 days postinfection, respectively (Fig. 2A). Similarly, in cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice, an inoculum of 2.5 × 105 resulted in 100% mortality by day 17 postinfection, with a median survival time of 7 days, whereas an inoculum of 4 × 104 caused only a 60% mortality by day 21 postinfection (Fig. 2B). Of note, R. oryzae 99-880 is more virulent in the DKA model than in the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate model (median survival time of the 2.5 × 105 inoculum is 4 days for DKA versus 8 days for cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice, P < 0.05). We also tried to give the mice a lower dose of cortisone acetate of 250 mg/kg combined with 200 mg/kg of cyclophosphamide. Only 50% to 70% mortality was achieved with an R. oryzae inoculum of 1 × 106 (data not shown). Subsequent experiments were conducted with an infectious inoculum of 2.5 × 105 spores, which consistently delivered 1.8 × 103 (9.5 × 102, 1.3 × 103) [median (25th quartile, 75th quartile)] spores to the lungs of DKA and cortisone acetate mice or to cyclophosphamide (200 mg/kg)-cortisone acetate (500 mg/kg) mice.

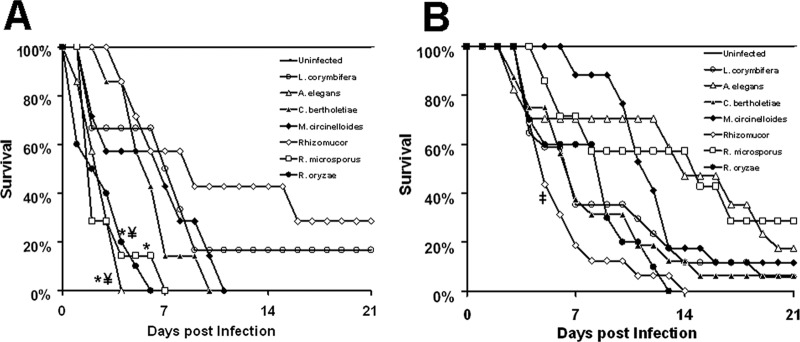

To evaluate the models in their ability to differentiate virulence among several clinical isolates of Mucorales, we compared the infectivity of several clinical isolates in their ability to cause infection in the DKA or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate models. Seven isolates that represent genera with clinical importance in mucormycosis were evaluated. For example, Rhizopus spp. are the most common cause of mucormycosis (6, 12), whereas Lichtheimia (49, 50) and Apophysomyces (8) are the second most isolated genera from European and Indian patients, respectively. Additionally, Cunninghamella infections are associated with a worse clinical outcome of mucormycosis (12). As shown in Fig. 3A, IT inoculation of DKA mice with either of the seven isolates differentiated them into three different groups of (i) highly virulent strains with a median survival time of 3 days (including R. oryzae, R. microspores, and A. elegans); (ii) moderately virulent strains that resulted in a median survival time of 6 to 7 days (including C. bertholletiae, M. circinelloides, and L. corymbifera); and (iii) weakly virulent strains, which included a Rhizomucor sp. that had a median survival time of 9 days and resulted in only 70% mortality after 21 days postinfection. In contrast, when the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice were infected, the Rhizomucor strain had the shortest median survival time of 5 days, followed by C. bertholletiae and L. corymbifera, which had a median survival time of 7 days (Fig. 3B). Unlike the DKA IT model, R. oryzae was moderately virulent in the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate model, with a median survival time of 9 days. Finally, in the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate model, weaker infections were noticed with M. circinelloides and A. elegans (median survival times of 12 and 14 days, respectively) as well as R. microsporus (median survival time of 15 days) (Fig. 3B). Hence, IT injection in both DKA and cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate models can differentiate the virulence among Mucorales isolates, and the same strain can have different virulence in response to the host. These results establish clinically relevant models of mucormycosis that can be utilized in future studies of Mucorales virulence and/or evaluating therapeutic interventions against mucormycosis.

Fig 3.

DKA and cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate murine models differentiated the virulence of Mucorales. Survival of DKA mice (n = 7 for all organisms except R. oryzae, for which n = 10 mice) (A) or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice (n = 17 mice for L. corymbifera, A. elegans, and M. circinelloides, n = 16 mice for C. bertholetiae and Rhizomucor, and n = 10 mice for R. oryzae from two independent experiments with similar results) (B) infected via intratracheal injection with different clinical isolates of Mucorales at a 2.5 × 105 inoculum. n = 7 mice for all organisms except for R. oryzae, in which n = 10 mice. *, P < 0.05 versus all other species; ‡, P < 0.01 versus M. circinelloides or R. microsporus by log rank test.

LAmB and POS improve survival of DKA or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice infected IT with R. oryzae.

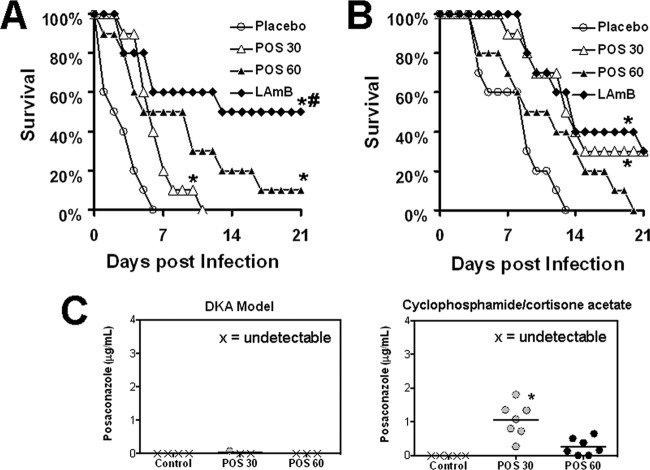

To validate our IT models, we evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of the commonly used LAmB and POS in treating DKA or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice infected with R. oryzae 99-880. In the DKA mice, both drugs improved survival time of mice infected with R. oryzae compared to placebo. However, LAmB demonstrated enhanced efficacy compared to POS at 30 mg/kg b.i.d. or 60 mg/kg/day (Fig. 4A). In contrast, LAmB or POS at 30 mg/kg b.i.d. showed similar activity in enhancing survival time of cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice compared to placebo, while POS at 60 mg/kg/day was not effective (Fig. 4B). These data correlated with the bioavailability of POS in the serum of cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate mice treated with 30 mg/kg b.i.d., which had higher levels of the drug than placebo-treated mice or those treated with POS at 60 mg/kg/day (1.06 ± 0.5 μg/ml for the 30 mg/kg b.i.d. versus 0.25 μg/ml for 60 mg/kg/day versus undetectable levels for placebo mice) (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, POS drug levels were not detected in the DKA mice regardless of the treatment regimens used (Fig. 4C). Because of these data, the 30-mg/kg/day treatment with POS was chosen in subsequent studies.

Fig 4.

LAmB and POS improved survival of mice infected IT with R. oryzae. DKA mice (A) or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice (B) (n = 10/group) were infected with R. oryzae 99-880 (average delivered inoculum = 3.4 × 103 spores per mouse). Sixteen hours postinfection, mice were treated intravenously with LAmB (15 mg/kg/day) or orally with POS (30 mg/kg b.i.d. or 60 mg/kg/day) or placebo. The treatment was terminated on day 7 postinfection. *, P < 0.004 for LAmB or POS therapy versus placebo; #, P < 0.02 for LAmB versus POS at 30 mg/kg b.i.d. by log rank test. (C) The POS levels in mouse sera (n ≥ 5) were evaluated on day 7 (4 h after administration of the last dose). Data are displayed as medians. The lower limit of detection is 0.125 μg/ml. *, P < 0.05 versus placebo or POS at 60 mg/kg/day by the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test.

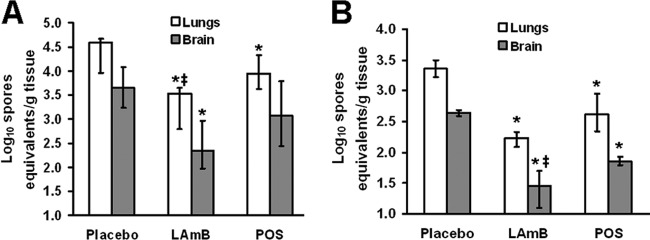

LAmB and POS treatment ameliorate the severity of mucormycosis in target organs.

To define the impact of antifungal therapy on tissue fungal burden in the DKA and cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate models, mice were infected through IT injection as described above and treated with LAmB (15 mg/kg/day), POS (30 mg/kg b.i.d.), or placebo. Treatment was initiated 16 h after infection and continued until day +3 relative to infection (three doses total for LAmB, six doses for POS), prior to the onset of deaths in the placebo group. Both drug treatments successfully reduced the severity of infection in the DKA and the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice. For example, compared to placebo, LAmB had a 1.1 and 1.3 log reduction in fungal burden of lungs and brains of DKA mice compared to that of placebo mice, respectively. Further, POS treatment caused a 0.8 log reduction in the lung fungal burden compared to that of the placebo but not in the brain fungal burden (Fig. 5A). Similarly, in the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice, LAmB treatment resulted in an ∼1.2 log reduction in the lungs and brain fungal burdens, while POS treatment had a reduction of 0.8 log in both organs compared to those of the placebo (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, while the difference is modest, LAmB also significantly reduced the tissue fungal burden of the lungs and brains of DKA and cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice, respectively, compared to POS treatment (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

LAmB and POS reduced tissue fungal burden in mice infected with R. oryzae. DKA mice (A) or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice (B) (n = 10/group) were infected with R. oryzae 99-880 (average delivered inoculum = 1.1 × 103 spores per mouse). Sixteen hours postinfection, mice were treated intravenously with LAmB (15 mg/kg/day) or orally with POS (30 mg/kg b.i.d.) or placebo. The treatment was terminated on day +3 relative to infection. Data are displayed as medians ± interquartile ranges. The y axes reflect lower limits of detection of the assay. *, P < 0.05 for LAmB or POS therapy versus placebo; ‡, P < 0.05 for LAmB versus POS by the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test.

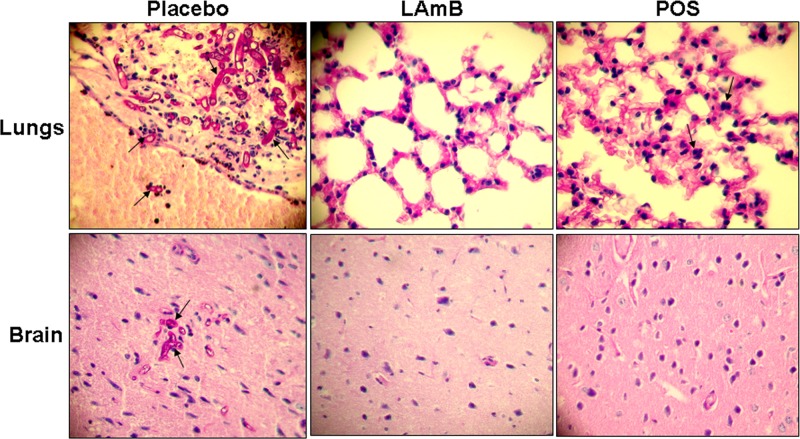

The survival and tissue fungal burden studies were corroborated in the histopathological examination in showing that LAmB and POS were effective at reducing the severity of the disease in the DKA model (Fig. 6). Briefly, lungs collected from placebo-treated mice showed abundant hyphal elements destroying the bronchus epithelium and invading blood vessels (angioinvasion), with clear signs of severe pneumonia. Similarly, sections of brains from placebo-treated mice demonstrated broad-ribbon-like aseptate hyphae typical of Mucorales accompanied with neutrophil infiltration and meningitis. In contrast, mice treated with LAmB or POS demonstrated normal histology of the two organs with no apparent fungal elements. The only exception was found in the lungs collected from mice treated with POS, which showed mild signs of pneumonia (Fig. 6). Similar results were obtained with samples taken from the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice, with less infection severity found in all samples compared to samples taken from the DKA mice (data not shown).

Fig 6.

Histopathology of lungs and brains from DKA mice infected IT with R. oryzae 99-880 and treated with placebo, LAmB (15 mg/kg/day), or posaconazole (30 mg/kg b.i.d.). PAS-stained sections of lungs and brains taken from placebo-treated mice showing abundant broad-ribbon-like hyphae (arrows) destroying the epithelium and invading blood vessel and signs of pneumonia (lungs) as well as signs of meningitis (brain). In contrast, sections of lungs and brains taken from mice treated with antifungal drugs showed minimal (POS) to no signs (LAmB) of disease. Arrows in POS demonstrate neutrophil infiltration into the lungs with mild pneumonia compared to placebo, with severe pneumonia. Magnification is 400×.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we developed an IT inoculation model of mucormycosis using DKA or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice. IT instillation has certain advantages over inhalation or intranasal inoculation. For example, unlike inhalation or intranasal inoculation, by using IT instillation the actual amount of spores delivered to the lungs of each animal can be essentially ensured (as demonstrated by the consistent delivery of ∼103 spores to the lungs, a phenomenon we could not duplicate using the intranasal model). Also, the technique is simpler than inhalation exposure procedures and minimizes risks to laboratory workers. Further IT instillation permits the introduction of a range of doses to the lungs within a short time and avoids exposure to the skin and pelt that can occur with inhalation exposure. However, a shortcoming of the model includes the bypassing of the upper respiratory tract (i.e., the sinus and nasal passages, oral passages, pharynx, and larynx), which can be important target sites for inhaled Mucorales in the development of rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Nevertheless, concordant with the clinical setting of the disease, our models result in initial pneumonia that rapidly hematogenously disseminates to other organs, including the brains and kidneys. Interestingly, we found R. oryzae 99-880 to be more virulent in the DKA IT model than in the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate model. This can be explained by the fact that the DKA model represents an environment rich in available serum iron that results in upregulation of the endothelial cell receptor GRP78 to which R. oryzae binds during tissue invasion and hematogenous dissemination (48).

Although no prospective randomized trials have compared antifungal agents for the primary treatment of invasive pulmonary mucormycosis, lipid formulations of amphotericin B are considered the first-line treatment for mucormycosis based on retrospective human data and on animal models. These studies showed LAmB to be more effective than amphotericin B deoxycholate (21, 25, 39). Our data showed that a high dose of LAmB is effective in protecting both DKA and cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice from mucormycosis induced by IT inoculation, essentially confirming our earlier findings with the intravenous model (25, 26).

POS is FDA approved for prophylaxis against fungal infections in high-risk neutropenic patients. Because of its in vitro activity against Mucorales, POS has been successfully used as a salvage treatment for mucormycosis, usually in combination with other therapies (51–53). However, the in vivo efficacy of POS in animal models demonstrated various degrees of success based on the animal model and the infectious Mucorales organism. For example, using an immunocompetent mouse model of hematogenously disseminated infection, Dannaoui et al. found POS to be effective against infection initiated by L. corymbifera while ineffective against R. oryzae infection despite using a susceptible strain (37). Similarly, POS was found to be effective in treating cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate mice infected with Mucor spp. (32). A more recent study showed a poor outcome of POS treatment of neutropenic mice infected with M. circinelloides (54), while the drug was effective, even more than amphotericin B, in treating immunocompetent mice infected intravenously with Apophysomyces variabilis (55) or Saksenaea vasiformis (56). We and others found that DKA or neutropenic mice infected intravenously with R. oryzae had limited benefit from POS treatment (27, 57, 58) despite the in vitro susceptibility of the used R. oryzae to POS (59, 60). To summarize, POS showed promising activity in treating mice (immunocompetent or suppressed) infected intravenously with Mucorales other than R. oryzae.

In this study and unlike our previous work which utilized mice infected intravenously (27), we found POS to be effective in treating DKA or cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate mice infected with R. oryzae. The POS protective activity was equivalent to that of LAmB in cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice but less than LAmB activity in the DKA mice. The in vivo activity of POS in both models was despite the high MFC value (25 μg/ml) registered in vitro against R. oryzae 99-880, suggesting that inhibition of the fungal growth at an MIC of 0.78 μg/ml is sufficient to ameliorate the disease in this model.

We also found dosing POS twice daily at 30 mg/kg to be more effective in protecting cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice from infection compared to POS given as a single dose at 60 mg/kg. These results can be explained by the higher serum levels of POS in the 30 mg/kg b.i.d. group, which were above the MIC levels of the drug. We also found POS serum levels in the DKA model to be negligible. It is well documented that diabetes and DKA are associated with gastrointestinal (GI) abnormalities, including general malabsorption, such as drug absorption due to alterations in gastrointestinal motility (61–63). We speculate these GI abnormalities to be responsible for the reduced levels of POS seen in serum samples collected from DKA mice. Interestingly, despite the undetectable levels of POS in the DKA model, the triazole was effective in treating R. oryzae infection with prolonged survival time, enhanced clearance of the mold, and mild to no signs of the disease in the target organs. Even though the trough POS serum levels were undetectable, it is possible that the peak serum levels were sufficient to have an antifungal effect. The enhanced efficacy of POS and maintaining of LAmB activity in the IT model could be attributed to the more clinically relevant route of infection and likely suggest this model to be more reliable in determining the efficacy of antifungal drugs. Finally, this model can be utilized for prophylactic evaluation of antifungal agents against mucormycosis, especially the cyclophosphamide-cortisone acetate-treated mice, since immunosuppressed individuals with a higher chance of developing mucormycosis are often treated prophylactically with antifungal agents.

In summary, we have developed murine models of IT mucormycosis that recapitulate the clinical disease and are capable of differentiating between the virulence of mucormycosis. The models were validated by testing the efficacy of two effective drugs in treating mucormycosis. These models likely prove beneficial in determining drug efficacy studies, studying pathogenesis of mucormycosis, and evaluating novel immunotherapeutic interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service contract HHSN272201000038I and grant R01 AI063503 to A.S.I. S.G.F. is supported by grant R01 AI073829. Research described in the manuscript was conducted partly at the research facilities of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Ibrahim AS, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG, Spellberg B. 2011. Mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis (zygomycosis), p 265–280 In Kauffman CA, Pappas PG, Sobel JD, Dismukes WE. (ed), Essentials of clinical mycology, 2nd ed Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennett JE. 1992. Mucormycosis, p 524–559 In Medical mycology. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sugar AM. 2005. Agents of mucormycosis and related species, p 2979 In Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. (ed), Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 6th ed Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, Bennett SD, Lo YC, Adebanjo T, Etienne K, Deak E, Derado G, Shieh WJ, Drew C, Zaki S, Sugerman D, Gade L, Thompson EH, Sutton DA, Engelthaler DM, Schupp JM, Brandt ME, Harris JR, Lockhart SR, Turabelidze G, Park BJ. 2012. Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011. N. Engl. J. Med. 367:2214–2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andresen D, Donaldson A, Choo L, Knox A, Klaassen M, Ursic C, Vonthethoff L, Krilis S, Konecny P. 2005. Multifocal cutaneous mucormycosis complicating polymicrobial wound infections in a tsunami survivor from Sri Lanka. Lancet 365:876–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. 2000. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:236–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spellberg B, Edwards J, Jr, Ibrahim JA. 2005. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:556–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chakrabarti A, Chatterjee SS, Das A, Panda N, Shivaprakash MR, Kaur A, Varma SC, Singhi S, Bhansali A, Sakhuja V. 2009. Invasive zygomycosis in India: experience in a tertiary care hospital. Postgrad. Med. J. 85:573–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marr KA, Carter RA, Crippa F, Wald A, Corey L. 2002. Epidemiology and outcome of mould infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:909–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rammaert B, Lanternier F, Zahar JR, Dannaoui E, Bougnoux ME, Lecuit M, Lortholary O. 2012. Healthcare-associated mucormycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54(Suppl 1):S44–S54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP. 2012. Pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54(Suppl 1):S16–S22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, Sein M, Sein T, Chiou CC, Chu JH, Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ. 2005. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:634–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chakrabarti A, Singh R. 2011. The emerging epidemiology of mould infections in developing countries. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 24:521–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gomes MZ, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. 2011. Mucormycosis caused by unusual mucormycetes, non-Rhizopus, -Mucor, and -Lichtheimia species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 24:411–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garcia-Hermoso D, Hoinard D, Gantier JC, Grenouillet F, Dromer F, Dannaoui E. 2009. Molecular and phenotypic evaluation of Lichtheimia corymbifera (formerly Absidia corymbifera) complex isolates associated with human mucormycosis: rehabilitation of L. ramosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3862–3870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, Roilides E, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP. 2012. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54(Suppl 1):S23–S34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Skiada A, Pagano L, Groll A, Zimmerli S, Dupont B, Lagrou K, Lass-Florl C, Bouza E, Klimko N, Gaustad P, Richardson M, Hamal P, Akova M, Meis JF, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Roilides E, Mitrousia-Ziouva A, Petrikkos G. 2011. Zygomycosis in Europe: analysis of 230 cases accrued by the registry of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) Working Group on Zygomycosis between 2005 and 2007. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:1859–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ashkenazi-Hoffnung L, Bilavsky E, Avitzur Y, Amir J. 2010. Successful treatment of cutaneous zygomycosis with intravenous amphotericin B followed by oral posaconazole in a multivisceral transplant recipient. Transplantation 90:1133–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hsieh TT, Tseng HK, Sun PL, Wu YH, Chen GS. 2013. Disseminated zygomycosis caused by Cunninghamella bertholletiae in patient with hematological malignancy and review of published case reports. Mycopathologia 175:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mayayo E, Klock C, Goldani L. 2011. Thyroid involvement in disseminated zygomycosis by Cunninghamella bertholletiae: 2 cases and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 19:75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gleissner B, Schilling A, Anagnostopolous I, Siehl I, Thiel E. 2004. Improved outcome of zygomycosis in patients with hematological diseases? Leuk. Lymphoma 45:1351–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kauffman CA. 2004. Zygomycosis: reemergence of an old pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:588–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kontoyiannis DP, Wessel VC, Bodey GP, Rolston KV. 2000. Zygomycosis in the 1990s in a tertiary-care cancer center. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:851–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Husain S, Alexander BD, Munoz P, Avery RK, Houston S, Pruett T, Jacobs R, Dominguez EA, Tollemar JG, Baumgarten K, Yu CM, Wagener MM, Linden P, Kusne S, Singh N. 2003. Opportunistic mycelial fungal infections in organ transplant recipients: emerging importance of non-Aspergillus mycelial fungi. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ibrahim AS, Avanessian V, Spellberg B, Edwards JE., Jr 2003. Liposomal amphotericin B, and not amphotericin B deoxycholate, improves survival of diabetic mice infected with Rhizopus oryzae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3343–3344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ibrahim AS, Gebermariam T, Fu Y, Lin L, Husseiny MI, French SW, Schwartz Skory JCD, Edwards JE, Spellberg BJ. 2007. The iron chelator deferasirox protects mice from mucormycosis through iron starvation. J. Clin. Invest. 117:2649–2657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ibrahim AS, Gebremariam T, Schwartz JA, Edwards JE, Jr, Spellberg B. 2009. Posaconazole mono- or combination therapy for treatment of murine zygomycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:772–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Waldorf AR, Ruderman N, Diamond RD. 1984. Specific susceptibility to mucormycosis in murine diabetes and bronchoalveolar macrophage defense against Rhizopus. J. Clin. Invest. 74:150–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lamaris GA, Ben-Ami R, Lewis RE, Chamilos G, Samonis G, Kontoyiannis DP. 2009. Increased virulence of Zygomycetes organisms following exposure to voriconazole: a study involving fly and murine models of zygomycosis. J. Infect. Dis. 199:1399–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Waldorf AR, Diamond RD. 1984. Cerebral mucormycosis in diabetic mice after intrasinus challenge. Infect. Immun. 44:194–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ibrahim AS, Gebremariam T, Fu Y, Edwards JE, Jr, Spellberg B. 2008. Combination echinocandin-polyene treatment of murine mucormycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1556–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun QN, Najvar LK, Bocanegra R, Loebenberg D, Graybill JR. 2002. In vivo activity of posaconazole against Mucor spp. in an immunosuppressed-mouse model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2310–2312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Waldorf AR, Levitz SM, Diamond RD. 1984. In vivo bronchoalveolar macrophage defense against Rhizopus oryzae and Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Infect. Dis. 150:752–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abe F, Inaba H, Katoh T, Hotchi M. 1990. Effects of iron and desferrioxamine on Rhizopus infection. Mycopathologia 110:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boelaert JR, de Locht M, Van Cutsem J, Kerrels V, Cantinieaux B, Verdonck A, Van Landuyt HW, Schneider YJ. 1993. Mucormycosis during deferoxamine therapy is a siderophore-mediated infection. In vitro and in vivo animal studies. J. Clin. Invest. 91:1979–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boelaert JR, Van Cutsem J, de Locht M, Schneider YJ, Crichton RR. 1994. Deferoxamine augments growth and pathogenicity of Rhizopus, while hydroxypyridinone chelators have no effect. Kidney Int. 45:667–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dannaoui E, Meis JF, Loebenberg D, Verweij PE. 2003. Activity of posaconazole in treatment of experimental disseminated zygomycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3647–3650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Spellberg B, Ibrahim AS, Chin-Hong PV, Kontoyiannis DP, Morris MI, Perfect JR, Fredricks D, Brass EP. 2012. The Deferasirox-AmBisome Therapy for Mucormycosis (DEFEAT Mucor) study: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:715–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ibrahim AS, Gebremariam T, Husseiny MI, Stevens DA, Fu Y, Edwards JE, Jr, Spellberg B. 2008. Comparison of lipid amphotericin B preparations in treating murine zygomycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1573–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zou Y, Tornos C, Qiu X, Lia M, Perez-Soler R. 2007. p53 aerosol formulation with low toxicity and high efficiency for early lung cancer treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 13:4900–4908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zou Y, Zong G, Ling YH, Hao MM, Lozano G, Hong WK, Perez-Soler R. 1998. Effective treatment of early endobronchial cancer with regional administration of liposome-p53 complexes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90:1130–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ibrahim AS, Bowman JC, Avanessian V, Brown K, Spellberg B, Edwards JE, Jr, Douglas CM. 2005. Caspofungin inhibits Rhizopus oryzae 1,3-beta-d-glucan synthase, lowers burden in brain measured by quantitative PCR, and improves survival at a low but not a high dose during murine disseminated zygomycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:721–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bowman JC, Abruzzo GK, Anderson JW, Flattery AM, Gill CJ, Pikounis VB, Schmatz DM, Liberator PA, Douglas CM. 2001. Quantitative PCR assay to measure Aspergillus fumigatus burden in a murine model of disseminated aspergillosis: demonstration of efficacy of caspofungin acetate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3474–3481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wiederhold NP, Najvar LK, Bocanegra R, Graybill JR, Patterson TF. 2010. Efficacy of posaconazole as treatment and prophylaxis against Fusarium solani. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1055–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sheppard DC, Rieg G, Chiang LY, Filler SG, Edwards JE, Jr, Ibrahim AS. 2004. Novel inhalational murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1908–1911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ma LJ, Ibrahim AS, Skory C, Grabherr MG, Burger G, Butler M, Elias M, Idnurm A, Lang BF, Sone T, Abe A, Calvo SE, Corrochano LM, Engels R, Fu J, Hansberg W, Kim JM, Kodira CD, Koehrsen MJ, Liu B, Miranda-Saavedra D, O'Leary S, Ortiz-Castellanos L, Poulter R, Rodriguez-Romero J, Ruiz-Herrera J, Shen YQ, Zeng Q, Galagan J, Birren BW, Cuomo Wickes CABL. 2009. Genomic analysis of the basal lineage fungus Rhizopus oryzae reveals a whole-genome duplication. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000549. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Avanessian V, Fu Y, Edwards JE., Jr 2005. Rhizopus oryzae adheres to, is phagocytosed by, and damages endothelial cells in vitro. Infect. Immun. 73:778–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liu M, Spellberg B, Phan QT, Fu Y, Lee AS, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG, Ibrahim AS. 2010. The endothelial cell receptor GRP78 is required for mucormycosis pathogenesis in diabetic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120:1914–1924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lanternier F, Dannaoui E, Morizot G, Elie C, Garcia-Hermoso D, Huerre M, Bitar D, Dromer F, Lortholary O. 2012. A global analysis of mucormycosis in France: the RetroZygo Study (2005-2007). Clin. Infect. Dis. 54(Suppl 1):S35–S43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schwartze VU, Hoffmann K, Nyilasi I, Papp T, Vagvolgyi C, de Hoog S, Voigt K, Jacobsen ID. 2012. Lichtheimia species exhibit differences in virulence potential. PLoS One 7:e40908. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tobon AM, Arango M, Fernandez D, Restrepo A. 2003. Mucormycosis (zygomycosis) in a heart-kidney transplant recipient: recovery after posaconazole therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:1488–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. van Burik JA, Hare RS, Solomon HF, Corrado ML, Kontoyiannis DP. 2006. Posaconazole is effective as salvage therapy in zygomycosis: a retrospective summary of 91 cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:e61–e65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Enoch DA, Aliyu SH, Sule O, Lewis SJ, Karas JA. 2011. Posaconazole for the treatment of mucormycosis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 38:465–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Salas V, Pastor FJ, Calvo E, Alvarez E, Sutton DA, Mayayo E, Fothergill AW, Rinaldi MG, Guarro J. 2012. In vitro and in vivo activities of posaconazole and amphotericin B in a murine invasive infection by Mucor circinelloides: poor efficacy of posaconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2246–2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Salas V, Pastor FJ, Calvo E, Sutton DA, Chander J, Mayayo E, Alvarez E, Guarro J. 2012. Efficacy of posaconazole in a murine model of disseminated infection caused by Apophysomyces variabilis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:1712–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Salas V, Pastor FJ, Calvo E, Sutton D, Garcia-Hermoso D, Mayayo E, Dromer F, Fothergill A, Alvarez E, Guarro J. 2012. Experimental murine model of disseminated infection by Saksenaea vasiformis: successful treatment with posaconazole. Med. Mycol. 50:710–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Spreghini E, Orlando F, Giannini D, Barchiesi F. 2010. In vitro and in vivo activities of posaconazole against zygomycetes with various degrees of susceptibility. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2158–2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rodriguez MM, Serena C, Marine M, Pastor FJ, Guarro J. 2008. Posaconazole combined with amphotericin B, an effective therapy for a murine-disseminated infection caused by Rhizopus oryzae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3786–3788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dannaoui E, Meletiadis J, Mouton JW, Meis JF, Verweij PE. 2003. In vitro susceptibilities of zygomycetes to conventional and new antifungals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sun QN, Fothergill AW, McCarthy DI, Rinaldi MG, Graybill JR. 2002. In vitro activities of posaconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B, and fluconazole against 37 clinical isolates of zygomycetes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1581–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shakil A, Church RJ, Rao SS. 2008. Gastrointestinal complications of diabetes. Am. Fam. Physician 77:1697–1702 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Scarpello JH, Sladen GE. 1978. Diabetes and the gut. Gut 19:1153–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hebbard GS, Sun WM, Bochner F, Horowitz M. 1995. Pharmacokinetic considerations in gastrointestinal motor disorders. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 28:41–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi, M38-A2. CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]