Abstract

Microsporidia comprise a large group of obligate intracellular parasites. The microsporidian Encephalitozoon cuniculi causes disseminated infection in immunosuppressed patients with HIV, cancer, or transplants and in the elderly. In vivo and in vitro studies on the effectiveness of drugs are controversial. Currently, there is no effective treatment. We tested albendazole, albendazole sulfoxide, metronidazole, and cyclosporine in mice immunosuppressed with cyclophosphamide and inoculated by the intraperitoneal route with 107 E. cuniculi spores. One week after experimental inoculation, the mice were treated with albendazole, albendazole sulfoxide, metronidazole, and cyclosporine. Histological and morphometric analyses were performed to compare the treated groups. The state of immunosuppression was evaluated by phenotyping CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry. Nontreated mice showed acute disseminated and fatal encephalitozoonosis. The treatment with benzimidazoles significantly reduced infection until 30 days posttreatment (p.t.), but at 60 days p.t., the infection had recurred. Metronidazole decreased infection by a short time, and cyclosporine was not effective. All animals were immunosuppressed by all the experiments, as demonstrated by the low number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. We conclude that no drug was effective against E. cuniculi, but the benzimidazoles controlled the infection transiently.

INTRODUCTION

Microsporidia are obligate intracellular parasites that have been recently reclassified from protozoa to fungi (1) and affect a wide variety of vertebrate and invertebrate hosts of all animal phyla (2). Microsporidia, especially Encephalitozoon spp. and Enterocytozoon spp., are considered to be emerging pathogens of increasing importance and a cause of opportunistic infection in immunosuppressed patients (3, 4), but other immunodeficiencies may also modify the host-parasite balance. They have various origins: pathological, other than AIDS (cytomegalovirus infections and cancers, such as leukemia); posttherapeutic (massive and prolonged corticotherapy and immunosuppressive treatments against transplant rejection); congenital deficiency in immunoglobulins; or even gerontological (3, 5, 6, 7). Out of more than 1,400 species of microsporidia described so far, 14 species were found to be important opportunistic pathogens in humans. Encephalitozoon cuniculi has been shown to cause nephritis, as well as secondary infections of the heart, brain, kidneys, and even the tongue (8).

The intracellular location of the developmental stages of microsporidia and high natural resistance of the wall of spore are factors that complicate the treatment and elimination of infections (9). The two most common drugs currently used to treat microsporidiosis in animals and humans are albendazole and fumagillin (10, 11, 12). However, most drug treatments do not fully eradicate the parasites, and preventive measures should be implemented, including the use of physical or chemical methods to destroy or inactivate infective spores present in the environment (10). The benzimidazole albendazole is a microtubule inhibitor that is effective against Encephalitozoon species of microsporidia that infect mammals; however, incomplete response and relapses have been documented (13).

Among the compounds tested in vitro, albendazole and fumagillin are the most effective and the least toxic to cells, while tetracycline derivatives are only partially effective or require toxic concentrations (14, 15). Albendazole remains the preferred drug in humans with encephalitozoonosis (16).

To evaluate new therapies against microsporidia, we tested the efficacy of the drugs albendazole, albendazole sulfoxide, metronidazole, and cyclosporine in experimental infection with E. cuniculi in immunosuppressed mice, mimicking opportunistic infections by microsporidia involving patients treated with immunosuppressive drugs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

All animal experiments used inbred male BALB/c mice (20 g) and were performed with the approval and oversight of the Ethics of Animal Experiments Committee of Paulista University under protocol 023/11, and all efforts were made to minimize the suffering of the animals. The study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Inbred BALB/c 30- to 40-day-old male mice, specific pathogen free (SPF), were maintained under standard animal housing conditions with Purina chow and water ad libitum while observing principles of laboratory animal care and laws on animal use. The animals were allowed free access to food and water and were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle. The mice were allowed to acclimate for 5 days after receipt from the vendor. The mice were kept in microisolator cages throughout the experimental period, divided into groups of 5 animals per cage and per type of treatment. To prevent reinfection, the microisolator cages, feed, water, and bedding were sterilized and changed daily. All interventions were performed in a laminar flow.

Established E. cuniculi infection model.

All animals were immunosuppressed with cyclophosphamide (100 mg/kg of body weight twice a week intraperitoneally [i.p.], starting the day before the inoculation of the parasite and throughout the experimental period) and inoculated with spores of E. cuniculi (17). The animals were immunosuppressed throughout the experimental period, even after the end of treatment. All animals were inoculated with 1 × 107 spores of E. cuniculi by the i.p. route. The spores of E. cuniculi used in this experiment were previously cultivated in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells.

Drugs.

Albendazole sulfoxide was obtained from Agener Animals Health (São Paulo, Brazil), albendazol from GlaxoSmithKline Ltd. (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), metronidazole from Sanofi-Aventis (Suzano, Brazil), cyclosporine from Novartis (São Paulo, Brazil), and cyclophosphamide from Asta Medica Oncologia (São Paulo, Brazil).

Treatment and its evaluation.

One week after experimental inoculation (7 days postinfection [p.i.]), the mice were allocated into experimental groups as follows: ABZ (n = 10), treated with albendazole (400 mg/kg, orally, twice daily for 3 weeks); SO-ABZ (n = 10), treated with albendazole sulfoxide (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally, once a day for 3 weeks); MTZ (n = 10), treated with metronidazole (500 mg/kg, orally, twice a day for 2 weeks); CsA (n = 10), treated with cyclosporine (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally, once a day for 3 weeks); and CNT (n = 10), control group (nontreated). Nonimmunosuppressed mice (not treated with cyclophosphamide; n = 12) were maintained throughout the experimental period to monitor the state of immunosuppression; half (n = 6) of them were infected with E. cuniculi, and the other half (n = 6) were not infected. Therapeutic success was evaluated using the survival rate (percent) 15, 30, and 60 days after the end of treatment (p.t.). Fragments of lung, brain, liver, kidneys, spleen, and intestines were removed on the same dates and fixed in 10% buffered formalin (pH 7.2 to 7.4). After staying in the fixative solution for 72 h, the material was subjected to dehydration, clearing, and embedding in paraffin and plastic resin for the investigation of E. cuniculi. Histological sections were mounted on glass slides and stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Gram-Chromotrope stain, and toluidine blue-fuchsin. In order to compare the different groups, morphometric analysis was performed on histological sections of three liver fragments taken from each animal and stained with H&E. For this procedure, we used the Optimas program (Optimas Corp., Edmonds, WA, USA). Three aspects were evaluated to compare the microsporidian infections in animals: the number of lesions produced by the parasite, the average area of lesions, and the area of the section occupied by lesions.

Phenotypic analysis.

To measure the immunosuppressive state, after dilution of the blood solution with hemolytic buffer and centrifugation three times (500 × g for 3 min), we obtained a pellet of leukocytes. The leukocytes were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with antibodies: rat anti-mouse L3T4 (IgG2a) was used to detect CD4+ T lymphocytes and anti-CD8a (IgG2a) for detecting CD8+ T cells, both conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (Pharmingen). Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur System flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with the CellQuest program. The group means were compared without distinction of dates.

Statistical methodology.

The histological data were subjected to descriptive statistics and to Kruskall-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests. For lymphocyte evaluation, the statistical program SPSS was used (SPPS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The significance of differences between groups of animals was tested by analysis of variance calculated by the minimal-square method. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The control group (cyclophosphamide-immunosuppressed mice) infected with E. cuniculi spores showed lethargy, weight loss, and increased abdominal volume, and some animals died after 30 days p.i. Gross necropsy lesions include hepatosplenomegaly and multifocal miliary white spots throughout the liver, spleen, lung, and cardiac tissue, starting at day 15 p.i. The animals died before completing the experimental period of 60 days.

Disseminated infection was characterized by random multifocal miliary granulomas, with various amounts of cell debris and suppurative necrosis observed in infected animals.

Liver.

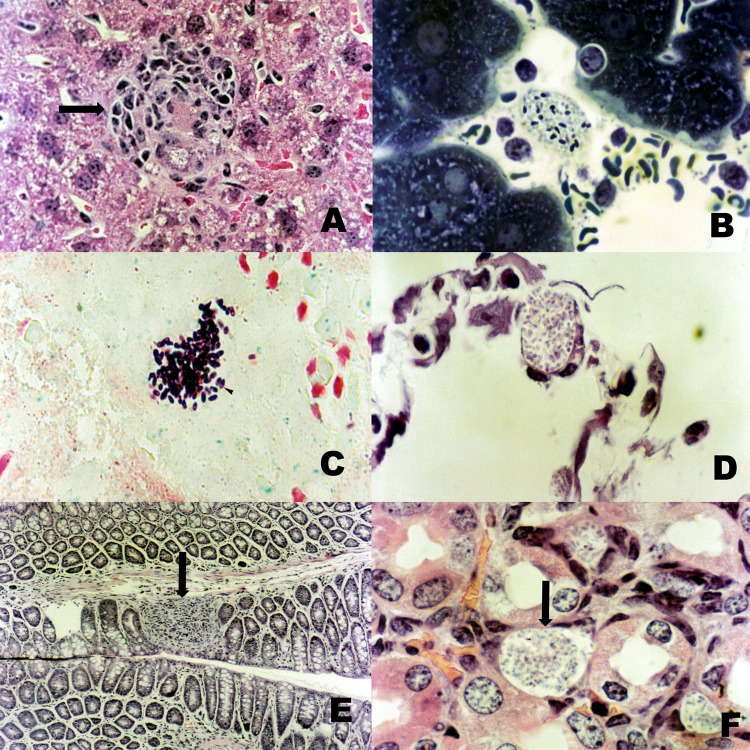

The liver was the organ first and most affected by the parasite, showing nodules of lymphocytic inflammatory cells with or without intracellular microsporidia (Fig. 1A) and with rare polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Hepatocytes were heavily infected, with the parasites occupying most of the cytoplasm. The Gram-positive parasites might be found free within foci of inflammation or intracellularly in macrophages, epithelium, or endothelium. Toluidine blue-fuchsin (Fig. 1B) and Gram-Chromotrope (Fig. 1C) stains showed the spores of the parasite stained purple or violet, sometimes with the presence of an equatorial halo.

Fig 1.

(A) Liver showing nodules of lymphocytic inflammatory cells with E. cuniculi spores (arrow) (H&E; ×400). (B) Spores of E. cuniculi stained by toluidine blue-fuchsin stain (×1,000). (C) Spores of E. cuniculi stained by Gram-Chromotrope stain (×1,000). (D) Spore collection observed in the alveolar septa (H&E; ×1,000). (E) Inflammatory infiltrates in the small intestine (arrow) (H&E; ×1,000). (F) Kidney showing lymphocytic inflammatory cells and E. cuniculi spores (arrow) (H&E; ×1,000).

Spleen.

An almost 2-fold increase in the size of the spleen was noted in the infected animals. Sections of spleen from cyclophosphamide-treated mice showed evidence of increased cell turnover and phagocytosis, but no intracellular parasites were seen. The spleens of cyclophosphamide-treated mice showed depletion of cells, especially of B-dependent areas of lymphoid follicles of the spleen, with numerous macrophages and cellular debris.

Lung.

The animals had varying degrees of degeneration, necrosis, and sloughing of the bronchiolar epithelium, and inflammatory infiltrates consisting of mononuclear cells were observed in the lung parenchyma, causing thickening of the alveolar septa. Collections of spores were observed in the alveolar septa, associated or not with inflammatory cells (Fig. 1D).

Intestine and kidneys.

The mice showed inflammatory infiltrates in the small intestine (Fig. 1E), glomerulonephritis (Fig. 1F), perinephritis, dystrophic calcification, and necrosis in renal tubules and a few granulomatous lesions in the brain.

The mice that were not immunocompromised and infected had a mild infection with the presence of few granulomas in the liver and absence of spores after 60 days of infection. No animal in this group developed symptoms or died in the experimental period.

Moreover, statistical analysis demonstrated a significant difference between the animals treated with albendazole sulfoxide or albendazole and the control group.

Albendazole and albendazole sulfoxide.

Treatment with benzimidazoles significantly reduced infection, since there were no histological lesions in animals at 15 and 30 days p.t. However, after 60 days p.t., we again found granulomatose lesions in the liver caused by Encephalitozoon, which had the same characteristics seen in untreated mice, but the size and extent of the lesions were considerably less, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of liver lesions in treated and untreated mice infected with E. cuniculi for 45, 60, and 90 days

| Treatment group | Days p.i. | No. of lesions/mm2a | Avg area of lesions (μm2)a | % of area occupied by lesionsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABZ | 45 | ND | ND | ND |

| 60 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 90 | 25.70 ± 3.87b | 78.21 ± 23.04b | 0.70 ± 0.10b | |

| SO-ABZ | 45 | ND | ND | ND |

| 60 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 90 | 35.90 ± 2,65b | 90.20 ± 33.04b | 0.97 ± 0.23b | |

| MTZ | 45 | 15.48 ± 29.42b | 58.21 ± 33.14b | 0.74 ± 0.25b |

| 60 | 56.23 ± 32.36b | 397.31 ± 121.05b | 6.10 ± 4.22b | |

| 90 | 93.42 ± 42.43 | 750.81 ± 423.04 | 10.97 ± 11.23 | |

| CsA | 45 | 90.06 ± 34.78 | 879.49 ± 631.81 | 11.20 ± 12.81 |

| 60 | 114.06 ± 26.78 | 998.49 ± 831.81 | 12.20 ± 10.61 | |

| 90 | NS | NS | NS | |

| CNT | 45 | 96.98 ± 25.43 | 975.22 ± 811.82 | 11.99 ± 11.63 |

| 60 | 124.79 ± 23.43 | 1100.22 ± 722.80 | 18.78 ± 10.57 | |

| 90 | NS | NS | NS | |

| Nonimmunosuppressed and infected | 45 | 45.70 ± 13.87 | 120.21 ± 23.04 | 1.05 ± 0.10 |

| 60 | 58.97 ± 22.36 | 135.15 ± 36.74 | 1.79 ± 0.25 | |

| 90 | 75.60 ± 19.43 | 148.68 ± 42.67 | 2.09 ± 0.36 |

Values are means ± standard deviations. ND, not detectable; NS, no survivors.

Significant difference (P < 0.05) between immunosuppressed (with cyclophosphamide) and infected mice (CNT) and treatment groups (ABZ, SO-ABZ, MTZ, and CsA).

Metronidazole.

Metronidazole significantly reduced the size and number of lesions at 15 and 30 days p.t., but the infection was present in all animals, and when evaluated at 60 days p.t., there was a recrudescence of the infection, since the size and number of lesions were similar to those in the immunosuppressed control group (Table 1).

Cyclosporine.

Treatment with cyclosporine did not significantly alter the course of infection. The number and size of lesions at 15 and 30 days p.t. were similar to those of the control group, and 60 days p.t., there were no surviving animals. The infection resulted in the death of all the animals before the end of the experimental period. The animals in this group had disseminated infection, as described in the control animals, affecting the liver, spleen, lungs, intestines, and nervous system.

The total percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in all immunosuppressed animals significantly decreased compared to the controls (not immunosuppressed with cyclophosphamide) at all dates and in all groups. As the means of the groups of animals, immunosuppressed and treated (ABZ, ABZ-SO, MTZ, and CsA) and untreated, did not differ significantly from each other, we compared the average obtained with the average of the groups of animals that were not immunosuppressed. The mean percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for immunosuppressed animals were, respectively, 1.38 ± 0.5 and 2.95 ± 1.1, considering all dates of analysis. Mice that were not immunosuppressed with cyclophosphamide and were uninoculated with E. cuniculi had mean percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively, of 18.35 ± 1.3 and 16.75 ± 1.2, showing that all animals presented the same level of immunosuppression and that the reduction of parasites was due to the actions of the drugs administered.

DISCUSSION

Reports of specific drug treatments for microsporidiosis include albendazole, thiabendazole, itraconazole, propamidine isethionate, fumagillin, chlorhexidine, metronidazole, polyhexamethylene biguanide, and benzimidazoles; however, their effectiveness remains doubtful (18, 19). Differences in clinical and parasitological responses to various therapeutic agents have emerged from clinical and in vitro studies, and the success varies from ineffective to very good. Immune reconstitution with antiretroviral therapies has greatly reduced the occurrence of microsporidiosis-associated clinical symptoms in persons with HIV infection (20), but the persistence of the infection remains a challenge for other susceptible hosts immunosuppressed by other conditions, such as chemotherapy treatments or transplant patients, or even in older people (6, 18).

Albendazole, a benzimidazole that inhibits microtubule assembly, was effective against several microsporidia, including the Encephalitozoon spp., but was less effective against Enterocytozoon bieneusi. This benzimidazole derivative, with broad-spectrum antihelminthic and antifungal activities, appears to be effective in the treatment of microsporidiosis (21, 22, 23). The drug interferes with tubulin polymerization and binds to the colchicine binding site of beta-tubulin (10). Albendazole therapy was effective in improving the clinical manifestations and decreasing the duration of the illness in children with diarrhea caused by microsporidia (24). We observed that the use of albendazole and albendazole sulfoxide reduced apparent infection up to 15 and 30 days p.t., but at 60 days p.t., the infection could be seen again. Therefore, neither benzimidazole compound was effective at stopping the infection of immunosuppressed animals. The two compounds can be used to reduce infection and its symptoms, but the patient cannot be considered cured.

Our results showed that metronidazole was not effective against microsporidia. Initially there was a reduction of the infection, denoted by the smaller number and size of lesions, but at the end of the experimental period, the infection of the treated group showed the same intensity as in the untreated control group. The action of metronidazole on microsporidial spores is uncertain, but it inhibits intracellular parasite proliferation and differentiation of Encephalitozoon intestinalis in cell culture. Clinical studies on the effectiveness of metronidazole in vitro have been largely disappointing (10), like our study.

Evidence indicates that cyclosporine has antiparasitic activity against toxoplasmosis (25) and schistosomiasis (26), probably caused by its binding to calmodulin, an important mediator of the effects of intracytoplasmic calcium, as this can block ion channels (27). It is known that changes in the concentration of calcium may interfere with the in vitro development of Encephalitozoon hellen. The low concentration of calcium can prevent the extrusion of the polar tubule (28), as well as prevent the development of other developmental intracellular stages of the species (29, 30). However, in our experiment, we found that cyclosporine treatment was not effective, because the mice treated with the drug had the same evolution as the control animals.

We conclude that albendazole and albendazole sulfoxide are partially effective; they control infection transiently and can be used to reduce symptoms of the infection. Metronidazole had little significant action in reducing infection. Cyclosporine produced a nonsignificant reduction in infection, suggesting that cyclosporine and related alkaloids should be further examined for antimicrosporidial activity. Note that these results apply to the specific dosages tested; using different doses may produce different results.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Lee SC, Corradi N, Byrnes EJ, Torres-Martinez S, Dietrich FS, Keeling PJ, Heitman J. 2008. Microsporidia evolved from ancestral sexual fungi. Curr. Biol. 18:1675–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anane S, Attouchi H. 2010. Microsporidiosis: epidemiology, clinical data and therapy. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 34:450–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ambroise-Thomas P. 2000. Emerging parasite zoonoses: the role of host-parasite relationship. Int. J. Parasitol. 30:1361–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferreira FMB, Bezerra L, Santos MB, Bernardes RM, Avelino I, Silva ML. 2001. Intestinal microsporidiosis: a current infection in HIV-seropositive patients in Portugal. Microbes Infect. 3:1015–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lores B, Lopez-Miragaya I, Arias C, Fenoy S, Torres J, Del Aguila C. 2002. Intestinal microsporidiosis due to Enterocytozoon bieneusi in elderly human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients from Vigo, Spain. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:918–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muñoz P, Valerio M, Puga D, Bouza E. 2010. Parasitic infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 24:461–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rabodonirina M, Cotte L, Radenne S, Besada E, Trepo C. 2003. Microsporidiosis and transplantation: a retrospective study of 23 cases. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 50:583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathis A, Weber R, Deplazes P. 2005. Zoonotic potential of the microsporidia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:423–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Didier ES. 2005. Microsporidiosis: an emerging and opportunistic infection in humans and animals. Acta Trop. 94:61–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Costa SF, Weiss LM. 2000. Drug treatment of microsporidiosis. Drug Resist. Updat. 3:384–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Canning EU, Lom J. 1986. The microsporidia of vertebrates. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 12. Didier PJ, Phillips JN, Kuebler DJ, Nasr M, Brindley PJ, Stovall ME, Bowers LC, Didier ES. 2006. Antimicrosporidial activities of fumagillin, TNP-470, ovalicin, and ovalicin derivatives in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2146–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Franzen C, MüIler A, Schwenk A, Salzberge Faitkenheuer BG, Mahrle G, Diehl V, Schrappe M. 1995. Intestinal microsporidiosis with Septata intestinalis in a patient with AIDS—response to albendazole. J. Infect. 31:237–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beauvais B, Sarfati C, Challier S, Derouin F. 1994. In vitro model to assess effect of antimicrobial agents on Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2440–2448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Waller T. 1979. Sensitivity of Encephalitozoon cuniculi to various temperatures, disinfectants and drugs. Lab. Anim. 13:227–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weber R, Deplazes P, Flepp M, Mathis A, Baumann R, Sauer B, Kuster H, Luthy R. 1997. Cerebral microsporidiosis due to Encephalitozoon cuniculi in patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 336:474–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lallo ML, Hirschfeld MPH. 2012. Encephalitozoonosis in pharmacologically immunosuppressed mice. Exp. Parasitol. 131:339–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Didier ES, Maddry JA, Brindley PJ, Stovall ME, Didier PJ. 2005. Therapeutic strategies for human microsporidia infections. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 3:419–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Franssen FF, Lumeij JT, Van Knapen F. 1995. Susceptibility of Encephalitozoon cuniculi to several drugs in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1265–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Didier ES, Stovall ME, Green LC, Brindley PJ, Sestak K, Didier PJ. 2004. Epidemiology of microsporidiosis: sources and modes of transmission. Vet. Parasitol. 126:145–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gritz DC, Holsclaw DS, Neger RE, Whitcher JP, Jr, Margolis TP. 1997. Ocular and sinus microsporidial infection cured with systemic albendazole. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 124:241–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johny S, Whitman DW. 2008. Effect of four antimicrobials against an Encephalitozoon sp. (Microsporidia) in a grasshopper host. Parasitol. Int. 57:362–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Katiyar SK, Edlind TD. 1997. In vitro susceptibilities of the AIDS-associated microsporidian Encephalitozoon intestinalis to albendazole, its sulfoxide metabolite, and 12 additional benzimidazole derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2729–2732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tremoulet AH, Avila-Aguero ML, París MM, Canas-Coto A, Ulloa-Gutierrez R, Faingezicht I. 2004. Albendazole therapy for Microsporidium diarrhea in immunocompetent Costa Rican children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 23:915–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mack CG, McLeod R. 1984. New micromethod to study the effects of antimicrobial agents on Toxoplasma gondii: comparison of sulfadoxine and sulfadiazine individually and in combination with pyremethamine and study of clindamycin, metronidazole, and cyclosporin A. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 26:26–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bout D, Deslee D, Capron A. 1984. Protection against schistosomiasis produced by cyclosporin A. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 33:185–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scheibel LW, Colobani PM, Hess AD, Aikana M, Atkinson CT, Milhous WK. 1987. Calcium and calmodulin antagonists inhibit human malaria parasites (Plasmodium falciparum): implications for drug design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84:7310–7314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nüssler AK, Thomson AW. 1992. Immunomodulatory agents in the laboratory and clinic. Parasitology 105:5–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leitch GJ, Scanlon M, Visvesvara GS, Wallace S. 1995. Calcium and hydrogen ion concentrations in the parasitophorous vacuoles of epithelial cells infected with microsporidium Encephalitozoon hellen. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 42:445–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leitch GJ, He Q, Wallace S, Visvesvara GS. 1993. Inhibition of the spore polar filament extrusion of the microsporidium, Encephalitozoon hellen, isolated from an AIDS patient. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 40:711–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]