Abstract

β-Lactamase inhibitory protein II (BLIP-II) is a potent inhibitor of class A β-lactamases. KPC-2 is a class A β-lactamase that is capable of hydrolyzing carbapenems and has become a widespread source of resistance to these drugs for Gram-negative bacteria. Determination of association and dissociation rate constants for binding between BLIP-II and KPC-2 reveals a very tight interaction with a calculated (koff/kon) equilibrium dissociation constant of 76 fM (76 × 10−15 M).

TEXT

Beta-lactam antibiotics are among the most often used antimicrobial agents (1). Bacterial resistance to these agents is increasing, and the resulting loss of treatment options is a threat to public health (2, 3). The major mechanism of bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics is the production of β-lactamase enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring to create ineffective antimicrobials (4). The carbapenem class of β-lactam antibiotics had been held in reserve as agents of last resort due to their resistance to the action of β-lactamases (5). However, β-lactamases capable of hydrolyzing carbapenem antibiotics are emerging in Gram-negative bacteria leading to resistance to these drugs. In particular, metallo-β-lactamases, such as NDM-1, and class A serine active site enzymes, including KPC-2, are a significant clinical threat (6, 7).

KPC-2 β-lactamase was first found in an isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae in North Carolina in 1996 (8). The gene encoding the KPC-2 enzyme is present within a Tn3 family transposon (Tn4401) on transferable plasmids (9). Strains of Enterobacteriaceae producing KPC β-lactamase have disseminated widely in the United States and many countries worldwide (10–12).

The β-lactamase inhibitory protein (BLIP) is a 165-amino-acid protein inhibitor of class A β-lactamases that was discovered in Streptomyces clavuligerus in 1990 (13). Interestingly, S. clavuligerus also produces the mechanism-based inhibitor, clavulanic acid, and so this organism produces both protein and small-molecule inhibitors of class A β-lactamases (14, 15). More recently, other BLIPs have been discovered; they include BLIP-I, which is 37% identical to BLIP and has a similar protein fold, and BLIP-II, which is unrelated in sequence and structure to BLIP and BLIP-I (16–18).

The structure of BLIP-II alone and in complex with TEM-1 or Bla1 β-lactamase reveals it has a seven-blade β-propeller fold type that utilizes a number of β-turns and loops to form interactions with the loop-helix region of β-lactamase from positions 99 to 114 (18, 19). Biochemical studies indicate that BLIP-II is a potent inhibitor of class A β-lactamases with binding constant (Kd) values in the picomolar range for the TEM-1, Bla1, SHV-1, CTX-M-14, SME-1 and Staphylococcus aureus PC1 enzymes (19, 20).

In this study, we investigated the potency of BLIP-II as an inhibitor of the KPC-2 carbapenemase. In previous studies of BLIP–β-lactamase interactions, we have utilized a β-lactamase inhibition assay to determine an inhibition constant (21, 22). However, preliminary experiments using the assay with BLIP-II and KPC-2 β-lactamase indicated that the potency was at least in the picomolar inhibition constant (Ki) range, and therefore, the low concentrations of enzyme necessary for an accurate assay are not possible, and the inhibition assay cannot be used.

The equilibrium dissociation constant for the BLIP-II and KPC-2 β-lactamase interaction was therefore obtained by determining the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants for the interaction. BLIP-II was purified for the binding experiments as described previously (19, 20). The protein concentration was determined by a Bradford assay, the results of which were compared with a standard curve calibrated by quantitative amino acid analysis. KPC-2 β-lactamase was expressed in Escherichia coli using an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in 20% sucrose and 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) at a ratio of 50 ml per liter of culture. The periplasmic materials were released by adding one-half volume of ice-cold water. After clarification by centrifugation (11,000 rpm for 30 min), the periplasmic materials were passed through an SP ion-exchange column to absorb unwanted proteins. The pass-through materials were adjusted to pH 5.8 using morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) acid and then passed through a stack of three 5-ml HiTrap SP cartridges. The bound proteins were eluted in an NaCl gradient of 0 to 1,500 mM in MES (pH 6) using a fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) system. Fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. Fractions containing highly pure KPC (>80%) were pooled, concentrated, and subjected to a Superdex 75 gel filtration sizing chromatography purification step. The resulting enzyme was greater than 90% pure as judged by SDS-PAGE. The KPC-2 concentration was determined by UV adsorption at 280 nm with an extinction coefficient of 39,545 M−1 cm−1.

The association rate constant was determined using an enzymatic activity assay as previously described (19). The experiment was performed in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) added at a concentration of 0.03 mg/ml. Aliquots (0.3 ml) were taken over time to measure the initial velocities of nitrocefin hydrolysis (optical density [OD] at 482 nm). The initial velocities are used as readouts of free enzyme with the time zero point being the maximum initial rate without the addition of BLIP-II. Nitrocefin was used at a concentration of 200 μM, and KPC-2 β-lactamase was used at 1 nM. The BLIP-II concentration was threefold higher than the β-lactamase concentration, allowing the association rate constants to be determined by second-order kinetics. We previously demonstrated that using second-order kinetics for analysis of the association rate is more suitable than using pseudo-first-order kinetics and yielded results that are within experimental error of the stopped-flow fluorescence spectrometry results (19). Inhibition of β-lactamase activity over time was therefore fitted to the second-order kinetic equation (equation 1),

| (1) |

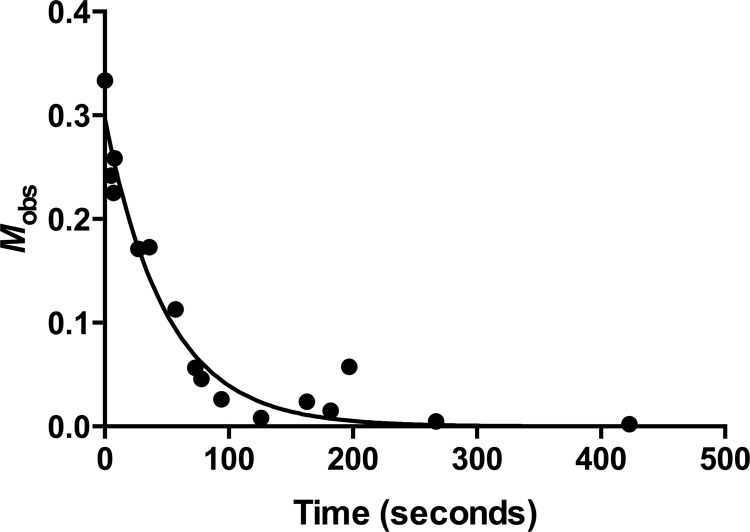

where Mobs is defined by the terms in equation 1 for simplicity in fitting and definition of the axis in Fig. 1, [E]t is the concentration of free β-lactamase estimated by the level of enzymatic activity at time t, [E]0 is the concentration of free β-lactamase before the addition of BLIP-II, [B]0 is the initial BLIP-II concentration in the reaction, C is a fitting constant representing the background rate of nitrocefin hydrolysis, t is the time after mixing (in seconds), and kon is the association rate constant of the interaction that is extrapolated from the data fitting (19). The experiments to determine the association rate constant were repeated four times, and all of the data sets were used to obtain the rate constant with an associated standard error through nonlinear regression. The results of the experiment are shown in Fig. 1, and using this curve fit, the association rate constant was determined to be 1.01 ± 0.11 × 107 M−1 s−1.

Fig 1.

Time course experiment of β-lactamase enzymatic activity demonstrating the fast association between BLIP-II and KPC-2. The association rate constant (kon) was extrapolated from fitting the data to the second-order kinetic equation. Mobs is defined by equation 1.

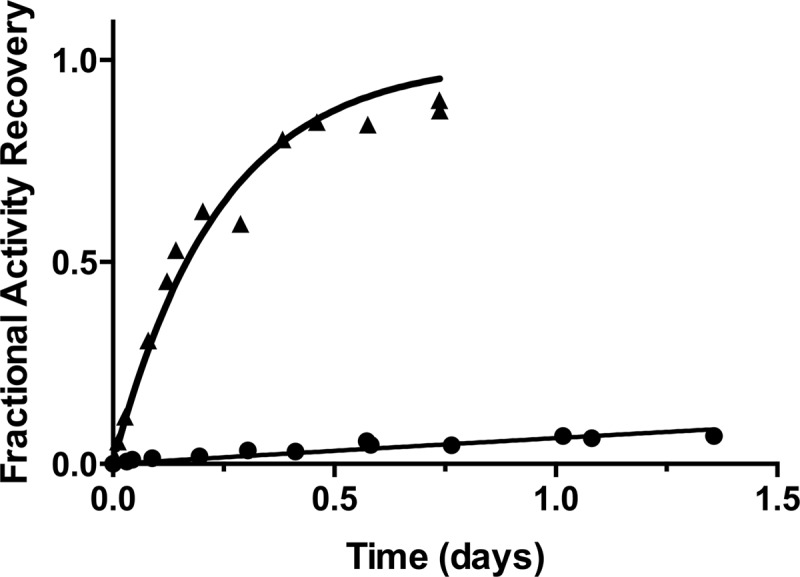

The dissociation rate constant was determined by measuring the recovery of the wild-type β-lactamase activity by competitive displacement with an inactive TEM-1 variant (Glu166Ala) as described previously (19). With this system, the inactive enzyme is present in large excess so that, upon dissociation of BLIP-II and KPC-2, the BLIP-II is bound by the inactive β-lactamase to prevent its rebinding to KPC-2. The experiment involved incubating BLIP-II in twofold excess with KPC-2 for 1 h. The BLIP-II–KPC-2 complex was then diluted into a 200 molar excess TEM-1 Glu166Ala competitor solution. As the BLIP-II dissociates from KPC-2 β-lactamase, it is bound by the excess TEM-1 Glu166Ala competitor rather than rebinding to KPC-2, so the dissociation reaction can be monitored by measuring the formation of free KPC-2 enzyme. The initial velocities of nitrocefin hydrolysis were measured to determine the amount of free wild-type KPC-2 enzyme. Nitrocefin was used at 200 μM, and KPC-2 was present at a concentration of 50 nM. The buffer used in this experiment was 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) supplemented with 1 mg/ml BSA. The BSA concentration used for this experiment was higher than the concentrations used in the association rate constant experiments to further stabilize the proteins over the extended time course. The amount of active β-lactamase over time was fitted with first-order kinetics to determine the kinetic parameters (equation 2),

| (2) |

where [E]∞ is the concentration of free β-lactamase when the dissociation had reached completion as estimated by the level of enzymatic activity not inhibited by BLIP-II, [E]t is the amount of free β-lactamase estimated by the level of enzymatic activity at time t, t is the time (in seconds) after mixing the BLIP-II–β-lactamase complex with the inactive TEM-1 E166A enzyme, C is the curve-fitting constant representing the background rate of nitrocefin hydrolysis (including the activity of the TEM-1 Glu166Ala enzyme), and koff is the dissociation rate constant extrapolated from fitting the data (19). The experiments to determine the dissociation rate constant were repeated three times, and all of the data sets were used to obtain the rate constant with an associated standard error through nonlinear regression. The results of this experiment are shown in Fig. 2, and the fitting indicated a dissociation rate constant (koff) of 0.77 × 10−6 ± 0.1 × 10−6 s−1.

Fig 2.

Enzymatic activity-based measurement of the slow dissociation of the BLIP-II–KPC-2 complex. In this experiment, the BLIP-II–KPC-2 complex is formed and then diluted in 200-fold excess of inactive β-lactamase competitor at time zero. The fractional activity recovery of free KPC-2 is determined by monitoring the activity over time compared to the uninhibited reaction (without BLIP-II). This recovered activity is then fit to the first-order kinetic equation (equation 2) to extrapolate the dissociation rate constant (koff). Symbols: black circles, wild-type BLIP-II; black triangles, BLIP-II Y191A mutant.

Complete recovery of free KPC-2 after formation of the BLIP-II–KPC-2 complex was not observed, because the uninhibited KPC-2 enzymatic activity begins to decay over time in the experiment shown. This observation is likely due to protein instability after ∼1.5 days at room temperature. To confirm the tight binding interaction of wild-type BLIP-II with KPC-2, a BLIP-II Y191A variant was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange method (Stratagene), purified, and subjected to the experiments described above. This variant was chosen after examining the structures that were previously determined (18, 19). The association and dissociation rate constants for the BLIP-II Y191A variant were determined to be 1.13 × 107 ± 0.15 × 107 M−1 s−1 and 48.2 × 10−6 ± 3.1 × 10−6 s−1, respectively. While this BLIP-II substitution did not impact the rate of association with KPC-2, the dissociation rate constant was drastically affected with a 63-fold increase (Fig. 2). This variant demonstrates that differences in the dissociation rate constants can be clearly observed with this approach and further confirms the rate measurements for the tight interaction between the wild-type BLIP-II and KPC-2 β-lactamase.

The kon and koff determinations of the BLIP-II–KPC-2 interaction were used to calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant (koff/kon), revealing that BLIP-II has very high affinity for binding to KPC-2 β-lactamase with a Kd of 7.6 × 10−14 M (76 fM). Because the on and off rate determinations are based on monitoring KPC-2 enzyme activity and inhibition kinetics and equilibrium inhibition assay results show that BLIP-II binding to KPC-2 inhibits the enzyme, we conclude that the binding constant, Kd, and the inhibition constant, Ki, are equivalent. Therefore, BLIP-II–KPC-2 is the most potent inhibitor–β-lactamase interaction reported for interactions of any BLIP family member with a class A β-lactamase and is among the most potent noncovalent inhibitors known for a β-lactamase. For example, BLIP is a potent inhibitor of KPC-2 with a Ki of 84 pM; however, this is ∼1,000-fold less potent than BLIP-II binding to KPC-2 (23).

The 76 fM Kd binding constant for the BLIP-II–KPC-2 complex is also among the tightest reported protein-protein interactions. The potency of the interaction is largely due to the very slow dissociation of the complex. Published association rate constants between proteins cover a wide range (<103 to >109 M−1 s−1) (24). A high-throughput study of antibody-antigen binding kinetics revealed association rates in the range of 105 to 106 M−1 s−1 (25). The BLIP-II–KPC-2 association rate is approximately 10-fold higher (107 M−1 s−1) than this but nevertheless is much lower than some of the fastest associating complexes such as barnase-barstar, which exhibits a kon rate of >5 × 109 M−1 s−1 (26, 27). In contrast, the antibody study revealed off rates in the 10−3 to 10−4 s−1 range, and the off rate for BLIP-II–KPC-2 is much lower at 0.77 × 10−6 s−1 (25). This koff rate reflects the long-lived nature of the BLIP-II–KPC-2 complex, which has a calculated half-life of 250 h (∼10 days).

Despite its highly potent inhibition of KPC-2 β-lactamase, the use of BLIP-II in combination with a carbapenem antibiotic as a therapeutic agent faces challenges. For example, with a molecular mass of 28 kDa, BLIP-II would not be expected to penetrate the bacterial outer membrane without the aid of facilitating molecules such as cell-penetrating peptides (28). In addition, BLIP-II would be subject to an immune response in humans without a masking molecule such as the attachment of polyethylene glycol (PEG) (29, 30). It is possible that a BLIP-II-derived peptide, such as a peptide containing residues 50 to 57 could bind the β-lactamase active site, but the potency of such a peptide would likely be much lower than that of BLIP-II. The high-affinity interaction between BLIP-II and KPC-2 could, however, be advantageous in the development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based diagnostic assay, since BLIP-II could be used to capture extremely low concentrations of KPC β-lactamase from clinical samples.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by NIH grant AI32956 to T.P.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Livermore DM. 2006. The β-lactamase threat in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter. Trends Microbiol. 14:413–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arias CA, Murray BE. 2009. Antibiotic-resistant bugs in the 21st century — a clinical super-challenge. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:439–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Livermore DM. 2012. Fourteen years in resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39:283–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bush K, Fisher JF. 2011. Epidemiological expansion, structural studies, and clinical challenges of new β-lactamases from Gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65:455–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Papp-Wallace KM, Endimiani A, Taracila MA, Bonomo RA. 2011. Carbapenems: past, present, and future. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4943–4960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nordmann P, Dortet L, Poirel L. 2012. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm. Trends Mol. Med. 18:263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nordmann P, Poirel L, Walsh TR, Livermore DM. 2011. The emerging NDM carbapenemases. Trends Microbiol. 19:588–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yigit H, Queenan AM, Anderson GJ, Domenech-Sanchez A, Biddle JW, Steward CD, Alberti S, Bush K, Tenover FC. 2001. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1151–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Naas T, Cuzon G, Villegas MV, Lartigue M-F, Quinn JP, Nordmann P. 2008. Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition of the β-lactamase blaKPC gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1257–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cuzon G, Naas T, Truong H, Villegas M-V, Wisell KT, Carmeli Y, Gales AC, Navon-Venezia S, Quinn JP, Nordmann P. 2010. Worldwide diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae that produces β-lactamase blaKPC-2 gene. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:1349–1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitchel B, Rasheed JK, Patel JB, Srinivasan A, Navon-Venezia S, Carmeli Y, Brolund A, Giske CG. 2009. Molecular epidemiology of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in the United States: clonal expansion of multilocus sequence type 258. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3365–3370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mathers AJ, Cox HL, Kitchel B, Bonatti H, Brassinga AKC, Carroll J, Scheld WM, Hazen KC, Sifri CD. 2011. Molecular dissection of an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae reveals intergenus KPC carbapenemase transmission through a promiscuous plasmid. mBio 2(6):e00204–11. 10.1128/mBio.00204-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doran JL, Leskiw BK, Aippersbach S, Jensen SE. 1990. Isolation and characterization of a β-lactamase-inhibitory protein from Streptomyces clavuligerus and cloning and analysis of the corresponding gene. J. Bacteriol. 172:4909–4918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brown AG. 1986. Clavulanic acid, a novel β-lactamase inhibitor – a case study in drug discovery and development. Drug Des. Deliv. 1:1–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neu HC, Fu KP. 1978. Clavulanic acid, a novel inhibitor of β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 14:650–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gretes M, Lim DC, de Castro L, Jensen S, Kang SG, Lee KJ, Strynadka NCJ. 2009. Insights into positive and negative requirements for protein-protein interactions by crystallographic analysis of the β-lactamase inhibitory proteins BLIP, BLIP-I, and BLP. J. Mol. Biol. 389:289–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kang SG, Park HU, Lee HS, Kim HT, Lee KJ. 2000. New beta-lactamase inhibitory protein (BLIP-I) from Streptomyces exfoliatus SMF19 and its roles on the morphological differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:16851–16856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lim D, Park HU, De Castro L, Kang SG, Lee HS, Jensen S, Lee KJ, Strynadka NCJ. 2001. Crystal structure and kinetic analysis of β-lactamase inhibitor protein-II in complex with TEM-1 β-lactamase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:848–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brown NG, Chow D-C, Sankaran B, Zwart P, Prasad BV, Palzkill T. 2011. Analysis of the binding forces driving the tight binding between β-lactamase inhibitory protein II (BLIP-II) and class A β-lactamases. J. Biol. Chem. 286:32723–32725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown NG, Palzkill T. 2010. Identification and characterization of beta-lactamase inhibitor protein-II (BLIP-II) interactions with beta-lactamases using phage display. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 23:469–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang Z, Palzkill T. 2003. Determinants of binding affinity and specificity for the interaction of TEM-1 and SME-1 β-lactamase with β-lactamase inhibitory protein. J. Biol. Chem. 278:45706–45712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang Z, Palzkill T. 2004. Dissecting the protein-protein interface between beta-lactamase inhibitory protein and class A beta-lactamases. J. Biol. Chem. 279:42860–42866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hanes MS, Jude KM, Berger JM, Bonomo RA, Handel TM. 2009. Structural and biochemical characterization of the interaction between KPC-2 beta-lactamase and beta-lactamase inhibitor protein. Biochemistry 48:9185–9193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schreiber G, Haran G, Zhou HX. 2009. Fundamental aspects of protein-protein association kinetics. Chem. Rev. 109:839–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wassaf D, Kuang G, Kopacz K, Wu Q-L, Nguyen Q, Toews M, Cosic J, Jacques J, Wiltshire S, Lambert J, Pazmany CC, Hogan S, Ladner RC, Nixon AE, Sexton DJ. 2006. High-throughput affinity ranking of antibodies using surface plasmon resonance microarrays. Anal. Biochem. 351:241–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schreiber G, Fersht AR. 1996. Rapid, electrostatically assisted association of proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:427–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schreiber G, Fersht AR. 1993. The interaction of barnase with its polypeptide inhibitor barstar studied by protein engineering. Biochemistry 32:5145–5150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koren E, Torchilin VP. 2012. Cell-penetrating peptides: breaking through to the other side. Trends Mol. Med. 18:385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cohen O, Kronman C, Lazar A, Velan B, Shafferman A. 2007. Controlled concealment of exposed clearance and immunogenic domains by site-specific polyethylene glycol attachment to acetylcholinesterase hypolysine mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 282:35491–35501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Veronese FM, Mero A. 2008. The impact of PEGylation on biological therapies. BioDrugs 22:315–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]