Abstract

Background. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections and outbreaks occur in correctional facilities, such as jails and prisons. Spread of these infections can be extremely difficult to control. Development of effective prevention protocols requires an understanding of MRSA risk factors in incarcerated persons.

Methods. We performed a case-control study investigating behavioral risk factors associated with MRSA infection and colonization. Case patients were male inmates with confirmed MRSA infection. Control subjects were male inmates without skin infection. Case patients and control subjects completed questionnaires and underwent collection of nasal swab samples for culture for MRSA. Microbiologic analysis was performed to characterize recovered MRSA isolates.

Results. We enrolled 60 case patients and 102 control subjects. Of the case patients, 21 (35%) had MRSA nasal colonization, compared with 11 control subjects (11%) (P<.001). Among MRSA isolates tested, 100% were the USA300 strain type. Factors associated with MRSA skin infection included MRSA nares colonization, lower educational level, lack of knowledge about “Staph” infections, lower rate of showering in jail, recent skin infection, sharing soap with other inmates, and less preincarceration contact with the health care system. Risk factors associated with MRSA colonization included antibiotic use in the previous year and lower rate of showering.

Conclusions. We identified several risks for MRSA infection in male inmates, many of which reflected preincarceration factors, such as previous skin infection and lower educational level. Some mutable factors, such as showering frequency, knowledge about Staph, and soap sharing, may be targets for intervention to prevent infection in this vulnerable population.

Community-associated (CA) methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection affects tens of thousands of Americans annually [1–4]. CA-MRSA is notable for its propensity to cause skin and soft-tissue infection and occasionally more-severe syndromes, such as necrotizing fasciitis and necrotizing pneumonia [5, 6]. The most commonly reported strain of CA-MRSA in the United States, the USA300 strain, has caused numerous outbreaks of infection in well-defined populations, such as infants in newborn nurseries, athletic teams, men who have sex with men, and residents of jails and prisons [1, 7, 8].

Many correctional facilities have high rates of CA-MRSA infection. The incidence of MRSA infection was 12 cases/1000 person-years in a study in the Texas correctional system [9]. The prevalence of MRSA nasal colonization in correctional facilities has ranged from none to 4.9% [10–12]. Correctional facilities are faced with unique challenges related to the control of CA-MRSA. These facilities are frequently characterized by crowded living conditions, suboptimal inmate hygiene, difficulty in providing clean uniforms and undergarments, and aging and deteriorating housing structures [13, 14]. In addition, the inmate population contains a disproportionate number of people who are homeless, have substantial health conditions (eg, human immunodeficiency virus infection, hepatitis B virus infection, or hepatitis C virus infection), have mental health comorbidities, and/or have a history of illicit drug use [15, 16]. Many incarcerated individuals move in and out of correctional facilities, potentially facilitating the transmission of CA-MRSA between the facilities and outside communities, as seen with other infectious diseases [17, 18]. With an estimated 2.3 million incarcerated persons in the United States, with 700,000 admissions and 700,000 releases annually [19, 20], the potential for MRSA spread to and from jails and prisons remains high.

Since the initial reports of CA-MRSA infection in 2002 [21], the Los Angeles (LA) County Sheriff's Department (California), in cooperation with the LA County Department of Public Health, has made efforts to control CA-MRSA in the LA County jails. These efforts include increasing surveillance, standardizing treatment protocols, increasing access to showers and soap, increasing education about MRSA, increasing the distribution of clean laundry, and enhancing environmental cleaning. Despite these efforts, CA-MRSA infections continue to occur. In 2005, the incidence of MRSA infection among male inmates was 13.8 cases/1000 admissions to the LA County jail facilities [22]. To better understand what contributed to spread and the potential effect of interventions, we conducted a case-control study to identify the risk factors for CA-MRSA colonization and infection at the LA County jail facilities.

Methods

Study population. This investigation took place in 2 LA County Sheriff's Department jail facilities for men from October 2006 through January 2007. These were the Twin Towers and the Men's Central Jail, a subset of which are numbered blocks that are dormitory-type units. The Men's Central Jail is the largest jail facility in the United States. The LA County jail system houses an estimated 18,300 inmates daily and has a mean duration of incarceration of 45 days. Most inmates are awaiting adjudication or sentencing; those who receive sentences of >1 year are sent to state prisons.

To enroll case patients with acute MRSA infection, nurses at the jail notified research personnel of patients in the medical clinic with skin infection before or within 24 hours of beginning antibiotic therapy. Patients were excluded if they were housed in a high-security area, were unwilling to participate, did not have a draining or drainable wound, or had taken antibiotics in the previous 21 days. Patients were considered to be case patients only if they had a culture-positive MRSA skin infection. Control subjects were clinic patients who were being evaluated for a reason other than a skin infection or inmates trusted at the clinic (eg, assisting medical staff). Initially, case patients and control subjects were to be enrolled in a 1:1 ratio in sufficient numbers to have >80% power (α = .05) to detect a 20% difference (10% vs 30%) in colonization prevalence between groups. However, final study enrollment was based on available resources.

Written consent was obtained from all participants, and subjects were given a $10 credit to their inmate account to compensate them for their time. This study was conducted in accordance with the policy for the protection of human research subjects of the Los Angeles Department of Public Health and the University of California, Los Angeles. The study was also reviewed and approved by the LA County Sheriff's Department.

MRSA risk factor survey. A standardized survey of MRSA risk factors was administered to participants through the use of an MP3 player. Subjects listened to questions through headphones and wrote answers on a response sheet that contained answer choices (but did not reiterate questions). This method was used to enhance confidentiality and to address concerns of low literacy among inmates [23]. The survey incorporated items used by the LA County Department of Public Health and previously published MRSA epidemiologic investigations [24, 25].

Microbiologic and molecular studies. Cotton-tipped swabs were used for obtaining wound samples for S. aureus culture from the patients with skin infection. Anterior nares swab samples for S. aureus culture were obtained from the patients with skin infection and the control subjects. Swab samples were transported immediately to the clinical microbiology laboratory and plated onto mannitol salt agar to identify S. aureus .All isolates were incubated aerobically for 48 hours at 35°C and then determined to be MRSA using BBL CHROMagar plates (Becton Dickson). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by broth microdilution, in accordance with the standards of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [26].

We typed all recovered S. aureus isolates. Isolates were inoculated into 2 mL of lysogeny broth and grown overnight at 37°C. The genomic DNA was then extracted using a DNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Cat. No. 69506). A polymerase chain reaction assay was used to test for the presence of pvl and mecA genes, as described elsewhere [27, 28]. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed; data analysis used GelCompar software (Applied Maths), in accordance with established methods [29]. A reference database from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that contains the patterns of USA strains was used to assign the PFGE types [29].

Statistical analysis. Data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute). Bivariate analysis was used to examine associations with potential MRSA skin infection risk factors from the questionnaire. Bivariate analysis was assessed by calculating odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P values by means of χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. All variables with P≥.10 in the bivariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Multivariate modeling procedures [30] were performed to predict MRSA skin infection. Multicolinearity for the logistic regression model was assessed by condition indices and variance decomposition proportions. Backwards elimination was performed using the Likelihood Ratio test to find the best model. Models were examined for goodness of fit using the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic. All variables were considered significant at the P = .05 level. Similar statistical analyses were performed for the MRSA nasal colonization analysis.

Results

Ninety-five (98%) of 97 patients with acute skin infection consented to participate in the study. Of the 95 patients with acute skin infection enrolled, 32 were excluded from the analysis because the wound isolate was not culture-positive for MRSA (6 cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S. aureus and 26 had no growth). Two patients were excluded from the analysis because of missing specimens. One other patient was excluded from analysis because he refused to fill out the survey. Therefore, a total of 60 case patients with MRSA infection were identified. Of 102 potential candidates approached to be control subjects, 100 were enrolled. The remaining 2 candidates were ineligible because they had received antibiotics in the previous 21 days.

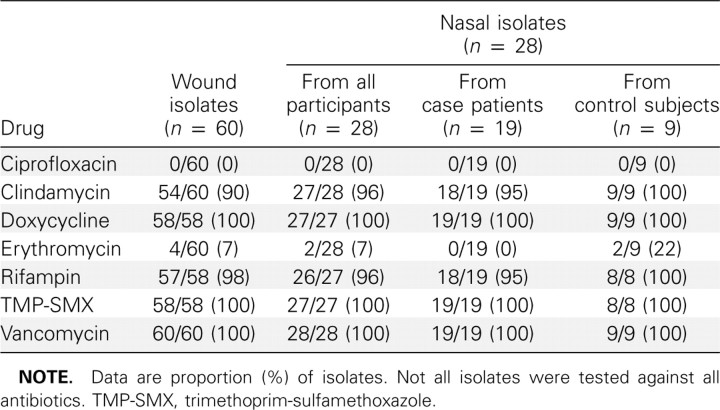

There were no significant differences between case patients and control subjects regarding demographic characteristics, comorbidities, or health care exposures (Table 1). MRSA colonization was found in 21 case patients (35%) and 11 control subjects (11%) (OR, 4.5; 95% CI, 2.0–10.0; P = .002).

Table 1.

Bivariate Analysis: Comparison of Risk Factors for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Skin Infection

Factors associated with MRSA skin infection. In the bivariate analysis, 11 factors were associated with MRSA skin infection (P<.05) (Table 1). In the multivariate logistic regression model (Table 2), variables significantly associated (P<.05) with MRSA skin infection included MRSA colonization of the nares, lack of college education, not having heard of “Staph” before enrolling in the study, having another skin infection in the previous 3 months, not showering daily in the jail in the previous week, sharing soap with other inmates, and lack of contact with a health care worker in the 3 months before jail entry.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis: Logistic Regression Model of Risk Factors for a Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Skin Infection

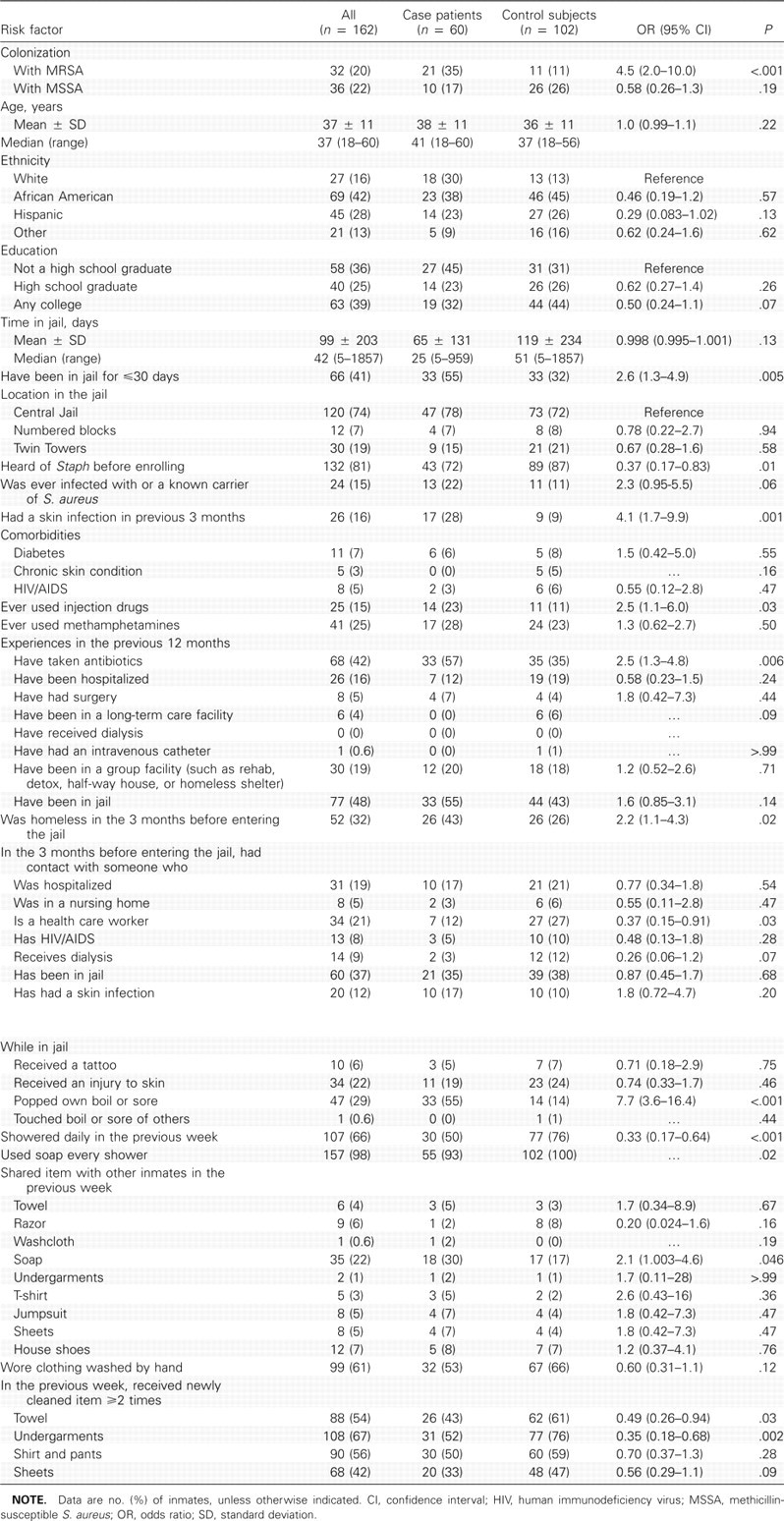

Factors associated with MRSA nasal colonization. In the bivariate analysis (Table 3), MRSA nasal colonization was associated (P<.05) with current MRSA skin infection (ie, being classified as a case patient), having been in jail ≤30 days, popping one's own boil or sore, having touched another's boil or sore while in the jail, not showering daily in the jail in the previous week, not receiving newly cleaned underclothing at ≥2 times in the previous week, having received antibiotics or having had surgery in the previous 12 months, and having resided in a group facility or having been jailed in the 12 months before current jail entry.

Table 3.

Bivariate Analysis: Comparison of Risk Factors for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Colonization of the Nares

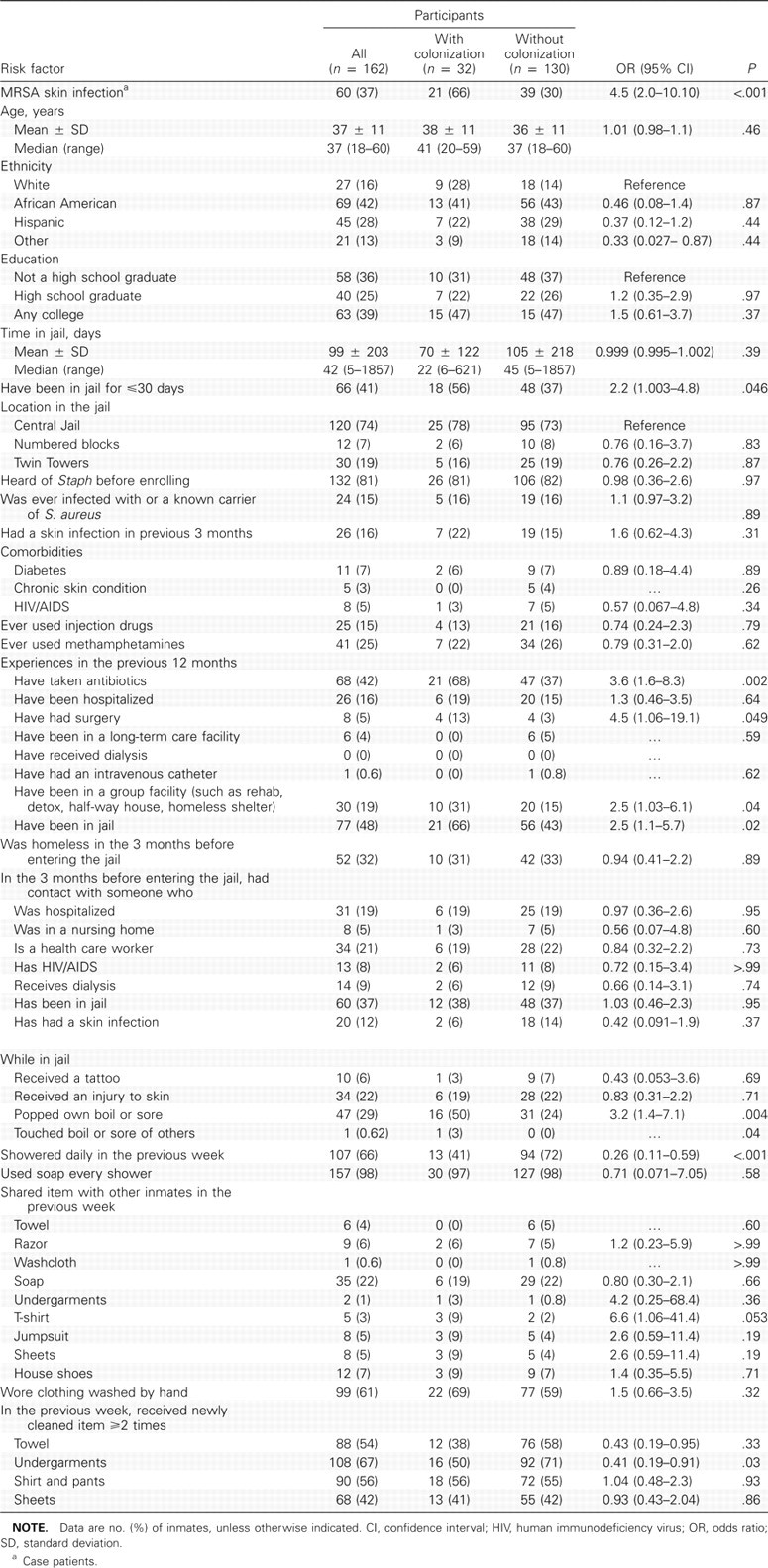

In the multivariate logistic regression model (Table 4), MRSA nasal colonization was significantly associated (P<.05) with current MRSA skin infection, receipt of antibiotics in the previous 12 months, and not showering daily in the jail in the previous week.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis: Logistic Regression Model of Risk Factors for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Colonization

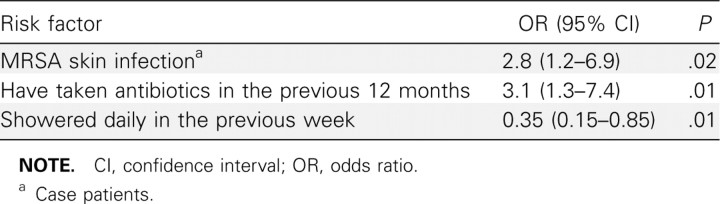

Microbiologic and molecular analysis. The antimicrobial susceptibility of the 92 MRSA isolates (60 case wound, 21 case nasal isolates, and 11 control nasal isolates) is shown in Table

5. Seventy-two isolates (78% of 92) were recovered from the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Of these 72 isolates, 50 were from the wounds of case patients and 22 were from the nares of case patients and control subjects. Remaining isolates were either lost or could not be subcultured after storage. All of the MRSA isolates tested contained SCCmec IV and had antibiotic susceptibility profiles typical of CA strains known to be circulating in LA County (Table 5) [25, 29, 31]. All 72 MRSA isolates were the USA300 strain by PFGE. Thirty-eight (53%) of the 72 isolates were indistinguishable from the LA County USA300 clone (all PFGE bands matched using the analysis software). There was very little variation among the isolates. All strains tested for pvl demonstrated its presence.

Table 5.

Profile of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates by Percentage Susceptible to Specific Drug

MRSA wound and nasal isolates from the same individual were available for 15 case patients. All but 1 pair of wound and nasal isolates were indistinguishable clones (ie, for 14 of the 15 case patients). The 1 pair in which the wound isolate and nasal isolate were distinguishable had a single band deletion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Banding patterns determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and a dendrogram showing the genetic relatedness of methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates recovered from inmates in the study. Case 1 represents a pair (1 nares isolate and 1 wound isolate) that were 96% similar but not indistinguishable (1 band deletion). All other inmates with paired nares and wound isolates (eg, case patients 2, 3, and 4) had indistinguishable isolates in the pair. USA300–0114 represents a reference strain. Controls 1, 2, and 3 represent PFGE patterns from MRSA isolates recovered from inmates with nasal colonization but without skin infection; these isolates were indistinguishable from the reference strain.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our investigation is the first case-control study investigating risk factors for MRSA skin infection and MRSA nasal colonization of jail inmates. Other investigations of MRSA in jails have focused on comparisons between MRSA infections and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus infections [32] and on circulating strains [33]. To identify potential MRSA risk factors that may be amenable to prevention efforts, we compared persons with and persons without MRSA infection. We found that in multivariable analysis, MRSA infection was associated with many preincarceration factors, such as lack of college education, not having heard of Staph, lack of contact with a health care worker in the previous 3 months, and having had a skin infection in the previous 3 months. These findings suggest that characteristics of the inmates that were immutable at the time of incarceration placed the person at risk for MRSA infection.

We also found 3 factors that were amenable to intervention within the jail: not showering daily in the jail in the previous week, not having heard of Staph, and sharing soap with other inmates. Identification of these factors suggests that there are some behaviors in jail that, if modified, may decrease MRSA infection risk. Increased access to daily showers, availability of liquid soap, and education about Staph all may be target interventions within the jail for prevention of MRSA infection. Similar to investigations in a prison population and a football team, we found that soap sharing and decreased frequency of showers were associated with MRSA infection [9, 31]. In 1 study, participants who reported sharing soap with other inmates had a 5 times greater likelihood of MRSA skin infection.

Efforts to encourage hygiene in incarcerated persons should be promoted. These efforts may include regular access to showers and provision of liquid or gel soaps or increased access to individual soaps to discourage sharing bar soap. Frequent uniform and towel laundering also may be key prevention components, although the association between MRSA and the frequency of receiving clean undergarments, seen in bivariate analysis, was not seen in multivariable analysis. MRSA screening and decolonization of incoming inmates may be a target of future investigation, given the high MRSA colonization rates among noninfected inmates. To better understand the transmission and pathogenesis of CA-MRSA within the jail setting, it would be necessary to conduct a prospective longitudinal investigation tracking the colonization and infection status of incoming inmates.

Educating inmates about Staph has been an intervention used by jail staff. The inverse relationship between MRSA infection and having heard of S. aureus suggests that educational efforts at the jail about Staph (MRSA) infection and prevention may have been successful. Although the exact mechanism by which knowledge about Staph is potentially protective against MRSA is unclear, knowing what Staph is may have led inmates to adopt habits to prevent this infection. Several other investigations have found that patient knowledge can be successful in changing behavior and improving outcomes [34, 35]. In fact, of the inmates who had heard about Staph, most heard about it from Sheriff's Department staff or jail flyers (data not shown), suggesting that these educational messages were successfully transmitted to inmates.

We found that the MRSA isolates available for typing were very similar to isolates that were causing infection in the LA County facility 4 to 5 years earlier [21]. It should be noted that the CA-MRSA isolates found in the nonincarcerated LA County population are of the same strain. In fact, in surveys conducted in Los Angeles several years before this investigation, USA300 caused 92% of CA-MRSA infections presenting to a single medical center [25] and approximately half of health care— and hospital-onset MRSA-associated skin infections [25, 36].

Because MRSA is endemic in LA County, the LA County jails go above the minimum standards for detention facilities mandated by the State of California [37]. Despite these efforts, there continued to be new cases of CA-MRSA infection during the study period. Other correctional facilities also have had challenges controlling MRSA infection. We also found a relatively high prevalence of MRSA nasal colonization among those who did not have a MRSA skin infection (11%). This prevalence of colonization found in noninfected patients may represent the high-risk population of incarcerated persons (eg, with high rates of illicit drug abuse and homelessness) rather than incident colonization during incarceration. We should note that MRSA nasal colonization in case patients may follow infection that occurred by means of skin-skin contact, and hence infection may have preceded nasal colonization [38]. Alternately, colonization may have preceded infection [38]. Our cross-sectional study design cannot assess directionality.

Because of the high-risk behaviors of some incarcerated individuals and because MRSA is endemic in LA County, we hypothesized that some people from the community come into the jail facilities already colonized or at risk for a skin infection. The “having been in jail for ≤30 days” variable suggests that many of the people at risk for a skin infection may have been at risk before entering the facility. Although this variable was significant in the bivariate analysis, it was not significant in the multivariate analysis. Longitudinal studies following a cohort of inmates from admission to release are required to fully examine incident infection and colonization.

The arguably low prevalence of nasal colonization in acutely infected persons (35%) may be due to the lack of sensitivity of sampling, because only the anterior nares were sampled and

not other body sites, such as the inguinal area or throat [39, 40]. Conversely, it may suggest that the pathogenesis of CA-MRSA is distinct from health care-associated MRSA and involves transmission from fomites or other persons [38, 39].

There are limitations to the study. It is possible that selection bias occurred with enrollment of both case patients and control subjects. Patients who were housed in the high-security incarceration areas or who were unwilling to speak to research personnel were not approached for the investigation. This enrollment technique may select for patients who are not representative of the underlying population. In addition, our control population was a convenience sample. However, because of logistic reasons brought about by the complex infrastructure of the jail, selection of a matched control population was unfeasible. Control subjects could have had a skin infection previously and may have developed a skin infection after taking part in the study, which may have resulted in misclassification of disease state for a few control subjects. However, we attempted to minimize this bias by excluding potential control subjects who had received antibiotics in the previous 21 days. Furthermore, misclassification bias of control subjects is independent of the main exposure (MRSA colonization) and results in bias toward the null hypothesis, so this bias may underestimate differences that we found between groups. There also may have been a reporting bias among inmates with skin infection in reporting poor sanitary conditions and inadequate clean laundry supply, because inmates may have felt pressure to respond “appropriately.”

There are strengths to our investigation. To our knowledge, this is the first case-control study to investigate both MRSA colonization and infection among an incarcerated population. Because of the relatively large number of inmates enrolled, we were able to perform multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the complex relationship of risk factors associated with MRSA colonization and infection. Another strength is that we used MP3-administered surveys to lower reporting bias. Responses were provided on answer sheets that did not display written questions, enhancing confidentiality.

In summary, we examined risk factors for CA-MRSA colonization and infection in a large jail facility. The populations and conditions inherent to correctional facilities make control of CA-MRSA especially challenging. Our findings pave the way for further study. Further investigation is needed to better understand the transmission and pathogenicity of CA-MRSA within closed environments. Such knowledge will be critical in selecting key areas in which to invest resources to end the transmission of the pathogen in these closed populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sheriff Leroy Baca, Lieutenant Stephen Smith, Chief Alex Yim, Captain Rodney Penner, the LA County Sheriff's Department, and the LA County Department of Public Health for their support and cooperation.

Financial support. Pfizer (2004–0316 to C.L.M.); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R01/CCR923419 to L.G.M.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no conflicts.

References

- 1.Chambers HF. The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus? Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:178–182. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naimi TS, LeDell KH, Como-Sabetti K, et al. Comparison of community-and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. JAMA. 2003;290:2976–2984. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Said-Salim B, Mathema B, Kreiswirth BN. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an emerging pathogen. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:451–455. doi: 10.1086/502231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salgado CD, Farr BM, Calfee DP. Community-acquired methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus: a meta-analysis of prevalence and risk factors. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:131–139. doi: 10.1086/345436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers HF. Community-associated MRSA—resistance and virulence converge. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1485–1487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King MD, Humphrey BJ, Wang YF, Kourbatova EV, Ray SM, Blumberg HM. Emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA 300 clone as the predominant cause of skin and soft-tissue infections. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:309–317. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Outbreaks of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections—Los Angeles County, California, 2002–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(5):88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis MW, Hospenthal DR, Dooley DP, Gray PJ, Murray CK. Natural history of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection in soldiers. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:971–979. doi: 10.1086/423965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in correctional facilities—Georgia, California and Texas 2001–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:992–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin or soft-tissue infections in a state prison—Mississippi. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:919–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowy FD, Aiello AE, Bhat M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection in New York State prisons. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:911–918. doi: 10.1086/520933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Main CL, Jayaratne P, Haley A, Rutherford C, Smaill F, Fisman DN. Outbreaks of infection caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a Canadian correctional facility. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16:343–348. doi: 10.1155/2005/698181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbons JJ, Katzenbach ND. Confronting confinement: a report of the Commission on Safety and Abuse in America's Prisons. New York: Vera Institute of Justice; 2006. Commission on Safety and Abuse in America's Prisons; Vera Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephan JJ. Census of jails, 1999 (report no. NCJ—186633) Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2001. United States Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammett TM, Harmon MP, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 1997. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1789–1794. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC. Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:840–846. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones TF, Craig AS, Valway SE, Woodley CL, Schaffner W. Transmission of tuberculosis in a jail. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:557–563. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-8-199910190-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leh SK. HIV infection in US correctional systems: its effect on the community. J Community Health Nurs. 1999;16:53–63. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn1601_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.One in 100: behind bars in America 2008. The Pew Center on the States. 2008. [Accessed January 11, 2009]. http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org/uploadedFiles/One%20in%20100.pdf. Published February 28, 2008.

- 20.Sabol WJ, Minton TD, Harrison PM. Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2006 (report no. NCJ 217675). Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2007. [Accessed October 26, 2010]. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/pjim06.pdf.

- 21.Hooton TM. The current management strategies for community-acquired urinary tract infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:303–332. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.County of Los Angeles Public Health Acute Communicable Disease Control Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Los Angeles County Jail: a 4-year review. 2005. [Accessed June 10, 2010]. http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/ACD/reports/spclrpts/spcrpt05/Mrsa2_SS05.pdf.

- 23.Al-Tayyib AA, Rogers SM, Gribble JN, Villarroel M, Turner CF. Effect of low medical literacy on health survey measurements. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1478–1480. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee NE, Taylor MM, Bancroft E, et al. Risk factors for communityassociated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1529–1534. doi: 10.1086/429827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, Bayer AS, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics cannot distinguish community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection from methicillinsusceptible S. aureus infection: a prospective investigation. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:471–482. doi: 10.1086/511033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 16th informational supplement. M100-S16. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lina G, Piemont Y, Godail-Gamot F, et al. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1128–1132. doi: 10.1086/313461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2155–2161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2155-2161.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDougal LK, Steward CD, Killgore GE, Chaitram JM, McAllister SK, Tenover FC. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: establishing a national database. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5113–5120. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5113-5120.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M, Pryor ER. Logistic regression: a self-learning text. Statistics for biology and health. 2nd. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen DM, Mascola L, Brancoft E. Recurring methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in a football team. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:526–532. doi: 10.3201/eid1104.041094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.David MZ, Mennella C, ansour M, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum RS. Predominance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among pathogens causing skin and soft-tissue infections in a large urban jail: risk factors and recurrence rates. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3222–3227. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01423-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tattevin P, Diep BA, Jula M, Perdreau-Remington F. Long-term followup of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus molecular epidemiology after emergence of clone USA300 in San Francisco jail populations. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:4056–4057. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01372-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown SA. Studies of educational interventions and outcomes in diabetic adults: a meta-analysis revisited. Patient Educ Couns. 1990;16:189–215. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(90)90070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larson EL, Ferng YH, McLoughlin JW, Wang S, Morse SS. Effect of intensive education on knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding upper respiratory infections among urban Latinos. Nurs Res. 2009;58:150–157. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181a30951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maree C, Daum RS, Boyle-Vavra S, Matayoshi K, Miller LG. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains causing healthcare-associated infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:236–242. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.California Code of Regulations (CCR) Minimum standards for local detention facilities. Title 15-crime prevention and corrections. Division 1, chapter 1, subchapter 4. 2008 Regulations. 2008. [Accessed June 12, 2010]. http://www.sdsheriff.net/jailinfo/title15.pdf.

- 38.Miller LG, Diep BA. Colonization, fomites, and virulence: rethinking the pathogenesis of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:742–750. doi: 10.1086/526773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang ES, Tan J, Eells S, Rieg G, Tagudar G, Miller LG. Body site colonization in patients with community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other types of S. aureus skin infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(5):425–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Widmer AF, Mertz D, Frei R. Necessity of screening of both the nose and the throat to detect methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in patients upon admission to an intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:835. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02276-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]