Abstract

Coinfection with bacteria is a major cause of mortality during influenza epidemics. Recently, Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists were shown to have immunomodulatory functions. In the present study, we investigated the effectiveness and mechanisms of the new TLR4 agonistic monoclonal antibody UT12 against secondary pneumococcal pneumonia induced by coinfection with influenza virus in a mouse model. Mice were intranasally inoculated with Streptococcus pneumoniae 2 days after influenza virus inoculation. UT12 was intraperitoneally administered 2 h before each inoculation. Survival rates were significantly increased and body weight loss was significantly decreased by UT12 administration. Additionally, the production of inflammatory mediators was significantly suppressed by the administration of UT12. In a histopathological study, pneumonia in UT12-treated mice was very mild compared to that in control mice. UT12 increased antimicrobial defense through the acceleration of macrophage recruitment into the lower respiratory tract induced by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB) pathway-dependent monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) production. Collectively, these findings indicate that UT12 promoted pulmonary innate immunity and may reduce the severity of severe pneumonia induced by coinfection with influenza virus and S. pneumoniae. This immunomodulatory effect of UT12 improves the prognosis of secondary pneumococcal pneumonia and makes UT12 an attractive candidate for treating severe infectious diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory infections account for a large proportion of deaths worldwide (1). In particular, influenza virus infection is life threatening for elderly individuals and immunocompromised patients. Pneumonia is a serious complication associated with influenza virus infection, and influenza-associated pneumonia can be classified into 2 categories, primary viral pneumonia and secondary bacterial pneumonia. While influenza infection can be lethal in and of itself, a substantial number of postinfluenza deaths are due to secondary bacterial pneumonias, most commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Haemophilus influenzae (2–9). Our previous study demonstrated that cytokine storms caused by an excessive host immune response are often the cause of the synergistic effect of influenza virus and S. pneumoniae, resulting in shorter survival periods and more severe lung inflammation in coinfected mice than in mice infected with either influenza virus or S. pneumoniae alone (10).

Toll-like receptor (TLR), a receptor protein found on the surface of animal cells, plays a critical role in the innate immune system. When microbes invade the host, TLR recognizes the pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipoprotein, flagellin of the flagellum, and double-stranded viral RNA. PAMPs are broadly shared by pathogens but distinguishable from host molecules, and detection of PAMPs by TLR proteins activates immune cell responses. Moreover, some TLR agonists were recently found to have anti-infective, antitumor, and antiallergic effects based on their functions as immune activators (11–14).

UT12 is an antibody generated against BaF3 cells overexpressing mouse TLR4. UT12 acts as an agonist of the TLR4/MD-2 complex and induces a stimulatory signal similar to the original ligand LPS (15). UT12 can induce the production of NF-κB and inflammatory cytokines involved in the innate immune system from peritoneal exudate cells in vitro (15). Previous studies have demonstrated that prophylactic treatment with TLR ligands enhances host immunity against influenza virus infection or pneumococcal infection alone (16, 17). However, no report has verified the effectiveness of the TLR agonist for an influenza virus/bacterium coinfection, which is more lethal than an infection with either pathogen delivered alone.

Therefore, in the present study, we sought to elucidate the mechanistic basis of the effects of UT12 treatment against severe pneumococcal pneumonia following influenza virus infection in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

UT12 was a gift from K. Fukudome (Saga Medical School, Saga, Japan). Clodronate liposomes were purchased from FormuMax Scientific (Palo Alto, CA). All primary antibodies for Western blotting were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). Secondary antibodies for Western blotting were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Inhibitors of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (SP600125), p38 (SB203580), MEK-1 (PD98059), and NF-κB (parthenolide) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Japan (Tokyo, Japan).

Mice.

CBA/JNCrlj mice (6-week-old males) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories Japan (Yokohama, Japan). C3H/HeJ and C3H/HeN mice (6-week-old males) were purchased from Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Laboratory Animal Center for Biomedical Research, Nagasaki University School of Medicine.

Virus and bacteria.

A mouse-adapted influenza virus strain, A/Puerto Rico 8/34 (H1N1) (PR8; a gift from K. Watanabe, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki, Japan), was grown in cultured MDCK cells. After 3 days, the supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C until use. The stored supernatant was thawed and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to the desired concentration just before inoculation. S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619, a clinical isolate with capsular serotype 19F, was prepared as previously described (18). Maintenance and storage of bacteria were performed as reported previously (10). Bacteria were grown in Mueller-Hinton II broth (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) with Strepto Haemo supplement (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) at 37°C for 6 h or until reaching log phase. The concentration of bacteria in the broth was determined by measuring the absorbance at 660 nm and then plotting the optical density on a standard curve generated by known CFU values. The bacterial culture was then diluted to the desired concentration for coinfection studies.

Mouse coinfection studies and UT12 treatment.

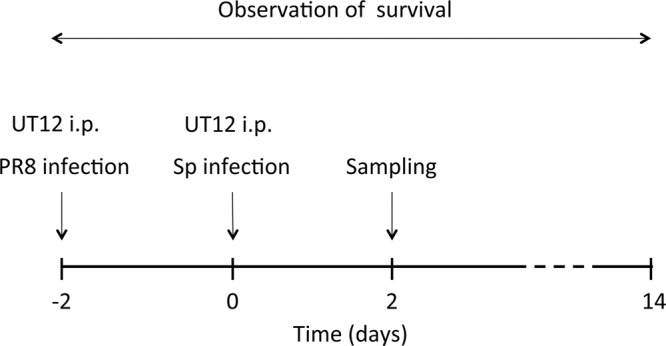

We performed viral challenge by intranasal (i.n.) inoculation of 5 × 103 PFU of PR8 in 50 μl PBS into mice anesthetized with pentobarbital. To induce pneumococcal superinfection, we intranasally inoculated 1 × 105 CFU of pneumococci in 50 μl of PBS into anesthetized mice 2 days after PR8 inoculation. Two hours prior to each inoculation, 1.0 μg of UT12 was intraperitoneally (i.p.) administered. A scheme of the study protocol is shown in Fig. 1. Samples of lungs and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were collected 2 days after pneumococcal inoculation.

Fig 1.

Schedule of coinfection experiments. Mice were administered i.n. influenza virus (PR8 strain, 5 × 103 PFU in 50 μl PBS), followed 2 days later by i.n. S. pneumoniae (1 × 105 CFU in 50 μl PBS). UT12 (1.0 μg) was intraperitoneally administered 2 h prior to each inoculation. PR8, influenza virus A/Puerto Rico 8/34 (H1/N1); Sp, S. pneumoniae.

Whole-lung preparations for CFU determination and histopathology.

Whole lungs were removed under aseptic conditions and homogenized in 1.0 ml PBS using a Shake Master NEO (Bio Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan). S. pneumoniae was quantified by placing serial dilutions of the lung homogenates onto blood agar plates and incubating them at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The remaining homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatants were used for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Lung tissue sections were paraffin embedded and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) using standard procedures (10, 19).

Bronchoalveolar lavage and BALF cell analysis.

Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed to assess inflammatory cell accumulation in the air space. The chest was opened to expose the lungs after the mice were anesthetized, and a disposable sterile feeding tube (Toray Medical Co., Chiba, Japan) was inserted into the trachea. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed using 1.0 ml PBS, and the recovered fluid was pooled for each animal. The BALF was then centrifuged onto a slide using a Cytospin 3 centrifuge (Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA) at 750 × g for 2 min and stained with Diff-Quik staining for differential cell counts.

Isolation and culture of peritoneal macrophages.

Three days after intraperitoneal injection of 4% sterile thioglycolate medium (2 ml), peritoneal macrophages were isolated by peritoneal lavage with Hanks buffer (without Ca2+ and Mg2+) containing 0.1% gelatin. Contaminating erythrocytes, granulocytes, and dead cells were removed by density gradient centrifugation for 45 min at 800 × g in Mono-Poly resolving medium according to the manufacturer's protocol (MP Biomedicals). Purified peritoneal macrophages were washed 3 times and cultured overnight in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Macrophage depletion.

Macrophages were depleted using clodronate liposomes as previously described (20). Clodronate liposomes (100 μl/mouse) were administered i.p. 24 h prior to pneumococcus inoculation. Administration of clodronate liposomes led to a >80% decline in the number of monocytes/macrophages compared with controls, as assessed in cytospin preparations 24 h after administration.

ELISA.

Concentrations of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC), macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), and MCP-1 in lung homogenates were assayed using mouse Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Concentrations of total and phosphorylated NF-κB were assayed using PathScan sandwich ELISA kits (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). These cytokine analyses were performed according to the manufacturers' protocols.

Western blotting.

Protein separation, transfer, blocking, and signal development were performed as described previously (10). For detection of intact and phosphorylated (activated) forms of JNK, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP)-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase 1 (MEK-1), and p38, rabbit primary antibodies against each kinase (total JNK, ab7964; p-JNK, ab32447; total MEK-1, ab75608; p-MEK-1, ab5613; total p38, ab7952; p-p38, ab32557) (Abcam Inc.) were used. Incubation with primary antibodies was followed by incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (sc-2030; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Statistics.

All data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by using StatView software (Abacus Concepts, Cary, NC). Survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and their homogeneity was evaluated by the log-rank test. Differences between 2 groups were tested for significance using unpaired t tests. Differences between multiple groups were tested for significance using 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences with P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

UT12 administration increased survival rates in coinfected mice.

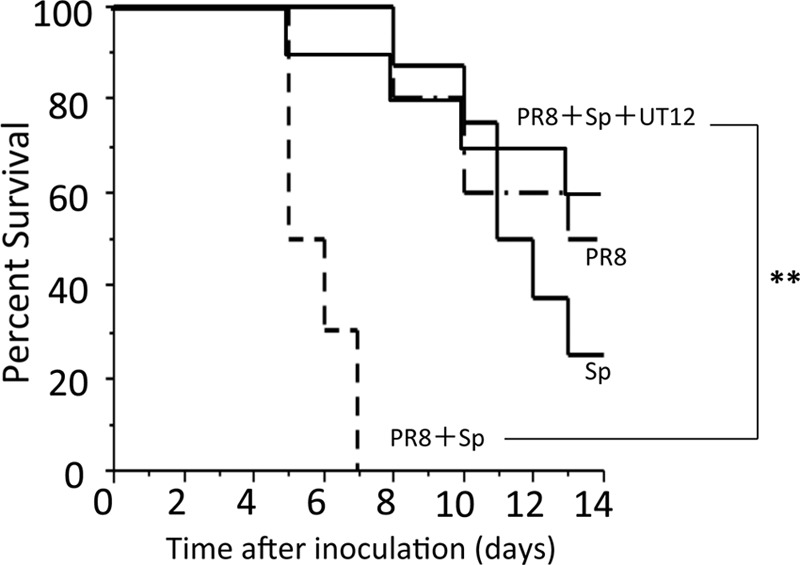

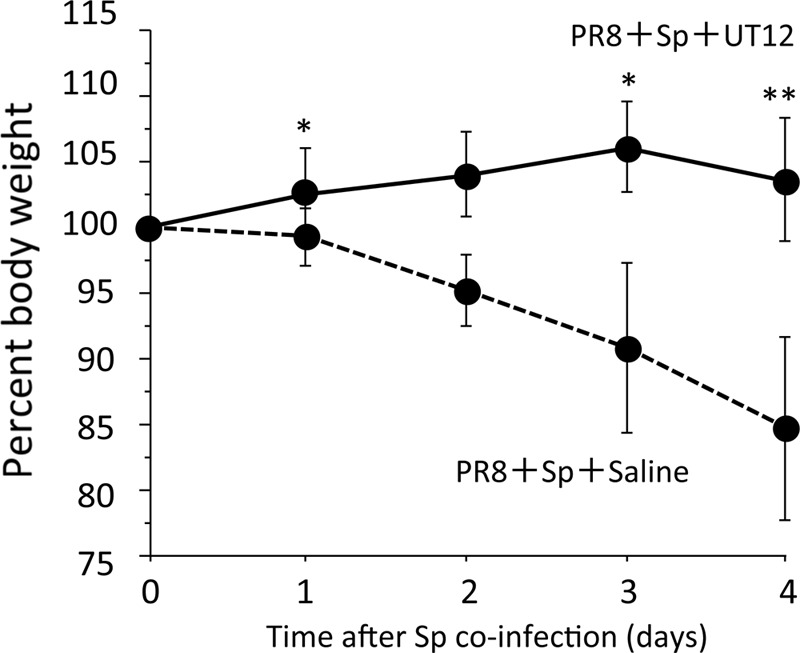

Mice coinfected with influenza A virus followed 2 days later by pneumococcus had a higher rate of mortality than mice infected with a single pathogen (Fig. 2), as reported previously (10). To assess the effects of UT12 in coinfected mice, we compared survival and body weight changes in UT12-treated mice with those in untreated mice. Treatment with UT12 increased the survival rate from 0% (control mice) to 60% at the end of the observation period (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Control mice lost an average of 15% of their body weight at day 4 after coinfection; in contrast, although body weight loss was observed later, UT12-treated mice maintained their body weight at least 4 days after secondary pneumococcal challenge (Fig. 3). These data indicated that UT12 decreased the mortality and loss of body weight induced by coinfection with influenza virus and S. pneumoniae.

Fig 2.

Administration of UT12 prior to pathogen exposure improves survival in coinfected mice. Influenza virus was inoculated 2 days before S. pneumoniae exposure (day 0). Percent survival of mice singly infected with influenza virus A/Puerto Rico 8/34 (H1/N1) (PR8) or S. pneumoniae (Sp) and coinfection of influenza virus and S. pneumoniae with or without UT12 was examined. The Kaplan-Meier curve shows survival rates of mice (PR8, n = 10; Sp, n = 8; PR8 plus Sp, n = 10; PR8 plus Sp plus UT12, n = 10). Statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test. **, P < 0.01.

Fig 3.

Body weight change was monitored. The body weight of UT12-treated mice was significantly higher at days 1, 3, and 4 than that of saline-treated control mice. The UT12-treated group (solid line; n = 10) and control group (dotted line; n = 10) are shown. PR8, influenza virus A/Puerto Rico 8/34 (H1/N1); Sp, S. pneumoniae. Values represent means ± standard deviations (SD). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

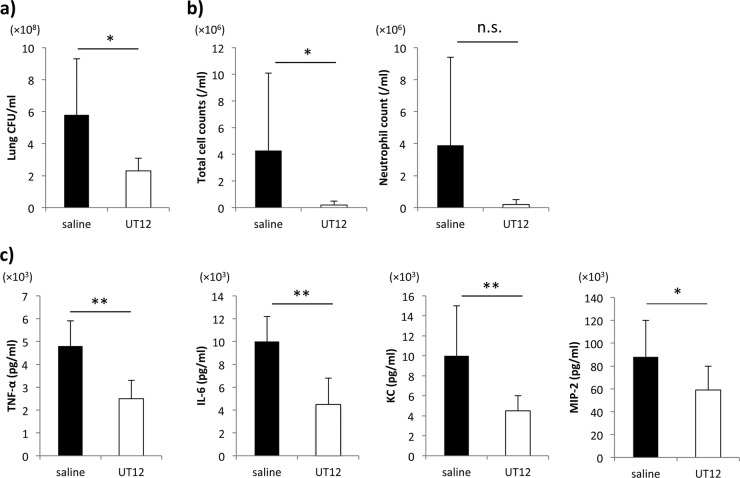

Bacterial burden and inflammation were reduced in the lungs of coinfected mice following administration of UT12.

There was a significant difference in the bacterial burdens of coinfected mice with and without UT12 treatment (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4a). While we attempted to examine viral titers after UT12 administration in mice infected with influenza virus alone and in mice coinfected with influenza virus and S. pneumoniae, no significant differences were observed (data not shown). Total cell counts in the BALF were significantly lower in UT12-treated mice than in the control mice (P < 0.05). In addition, neutrophil counts were also decreased by UT12 treatment, although the difference was not significant (P = 0.10) (Fig. 4b).

Fig 4.

Prophylactic UT12 administration inhibits bacterial burden and excessive proinflammatory cytokine production induced by coinfection in the lung. (a) The numbers of viable S. pneumoniae after coinfection. (b) Total cell and neutrophil count in BALF. (c) Concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines. Each examination was performed 2 days after S. pneumoniae infection. Each group contained 7 mice. Values represent means ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant.

Robust innate proinflammatory cytokine expression can cause direct tissue insult and recruit inflammatory cells that can potentially destroy tissue (21, 22). The percent survival in coinfected mice was increased by UT12 administration, and we hypothesized that UT12 might protect a host from severe lung injury by preventing cytokine storms through the reduction of host sensitivity against pneumococcal infection. As shown in Fig. 4c, after coinfection, the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, KC, and MIP-2 were significantly suppressed in UT12-treated mice compared to control mice (TNF-α, P < 0.001; IL-6, P < 0.001; KC, P < 0.01; MIP-2, P < 0.05).

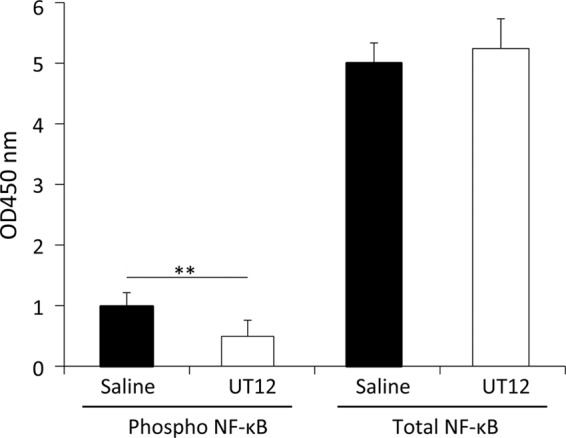

Furthermore, we assayed concentrations of NF-κB, a transcription factor that plays critical roles in inflammation, in the lungs of mice coinfected with the 2 pathogens. Excessive activation of NF-κB can induce a cytokine storm, resulting in septic shock (23). In the current study, the levels of activated NF-κB in the lung homogenates after coinfection were significantly suppressed by UT12 administration (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). These data suggest that UT12 might attenuate the expression of cytokines and activation of intracellular signal transduction pathways via TLR signaling.

Fig 5.

Phosphorylated and total NF-κB concentrations in lung homogenates. Each examination was performed 2 days after S. pneumoniae infection. Each group contained 7 mice. Values represent means ± SD. **, P < 0.01.

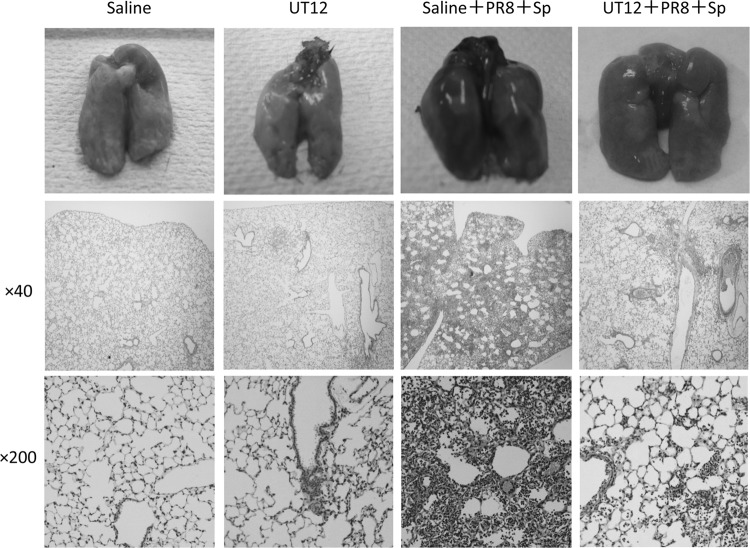

Histopathological analysis of coinfected lungs revealed marked reductions in tissue injury, inflammatory cell accumulation, pulmonary hemorrhage, and edema in UT12-treated mice (Fig. 6). Taken together, our data indicated that UT12 might have a substantial therapeutic effect on severe pneumococcal pneumonia induced by coinfection with influenza virus, through inhibition of inflammatory cell responses and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production in the lungs.

Fig 6.

UT12 administration protects the host from acute lung injury induced by coinfection. Histopathological analysis of the lungs. Lungs were collected 2 days after S. pneumoniae coinoculation. Photographs of whole lungs and hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained tissue sections at magnifications of ×40 and ×200. PR8, influenza virus A/Puerto Rico 8/34 (H1/N1); Sp, S. pneumoniae.

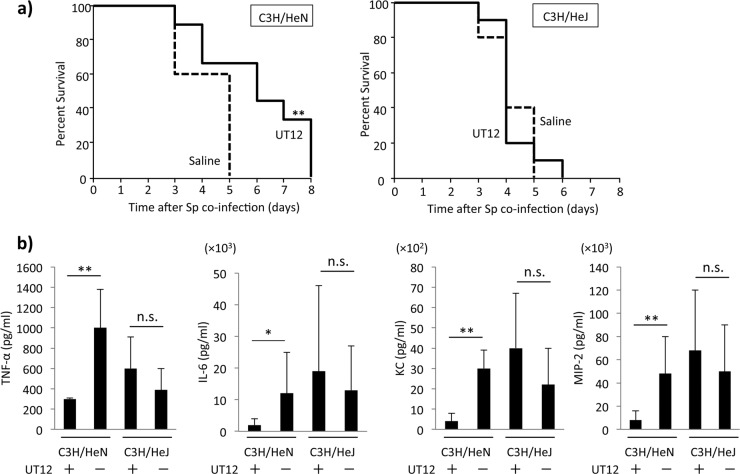

The anti-inflammatory effects mediated by UT12 were TLR4 specific.

Mice with intact (C3H/HeN) and nonfunctional (C3H/HeJ) TLR4 were treated with UT12 prior to individual inoculation. Treatment with UT12 delayed mortality but did not impact overall survival in coinfected C3H/HeN mice compared to those treated with vehicle (Fig. 7a). However, percent survival was not significantly different between C3H/HeJ mice treated with UT12 and those treated with vehicle (Fig. 7a). An analysis of TNF-α, IL-6, KC, and MIP-2 concentrations in the lungs of coinfected mice showed that UT12 significantly attenuated proinflammatory cytokine production in C3H/HeN mice but not in C3H/HeJ mice (Fig. 7b). These results indicated that the anti-inflammatory effects of UT12 during coinfection with influenza virus and pneumococcus were primarily TLR4 specific, although the TLR4-dependent inflammatory response was not completely abolished in C3H/HeJ mice.

Fig 7.

UT12-mediated protection against pneumococcal infection is TLR4 specific. (a) Percent survival in coinfected C3H/HeN and C3H/HeJ mice with or without UT12 treatment. (b) Concentration of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the lung at day 2 after S. pneumoniae coinfection. C3H/HeJ mice treated with UT12 (n = 4), C3H/HeJ mice treated with saline (n = 4), C3H/HeN mice treated with UT12 (n = 5), and C3H/HeN mice treated with saline (n = 4), respectively, from left to right. Sp, S. pneumoniae; Kaplan-Meier curve with survival rates of mice (C3H/HeN with UT12 treatment group, n = 15; the other groups, n = 10). Statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test. Values represent means ± SD; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant.

UT12 induced migration of mononuclear cells into the lower respiratory tract by promotion of MCP-1 production from alveolar macrophages.

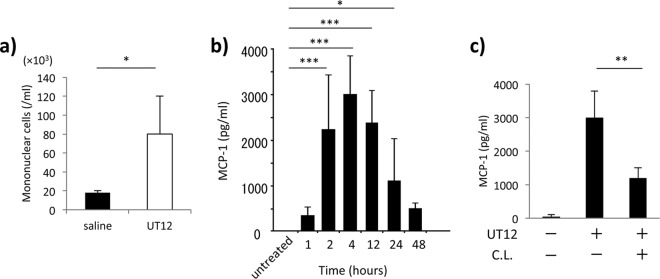

Macrophages are responsible for the majority of cell-mediated bacterial clearance after infection and are key participants in the acute inflammatory response. Therefore, we next assessed the effects of UT12 treatment on the recruitment of macrophages to the primary site of infection. BALF was obtained from mice 4 h after i.p. treatment with UT12. Interestingly, the number of mononuclear cells in the BALF of UT12-treated mice was significantly increased compared to that in vehicle-treated mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8a).

Fig 8.

Resident macrophages are required for UT12-mediated promotion of recruitment of macrophages via MCP-1-dependent enhancement. (a) Mononuclear cell count in BALF 4 h after saline or UT12 administration was examined by cytospin. (b) Time course of the level of MCP-1 concentrations in the lung after UT12 administration. Values at each time point after UT12 administration were compared with those in untreated mice. (c) Concentrations of MCP-1 in the lung 4 h after UT12 administration with or without UT12 and clodronate liposome (C.L.) treatment. Values represent means ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

MCP-1 is a chemokine that recruits mononuclear cells to the infectious source. The production of MCP-1 in the lungs was markedly increased after UT12 administration; MCP-1 levels peaked at 4 h and remained high at 48 h after UT12 administration (Fig. 8b). Because much of the MCP-1 in the lung is produced by alveolar macrophages (24), we performed macrophage depletion experiments with clodronate liposomes to examine whether resident macrophages were involved in the UT12-mediated production of MCP-1 (20, 25). As shown in Fig. 8c, macrophage depletion suppressed the production of MCP-1 in response to UT12 stimulation.

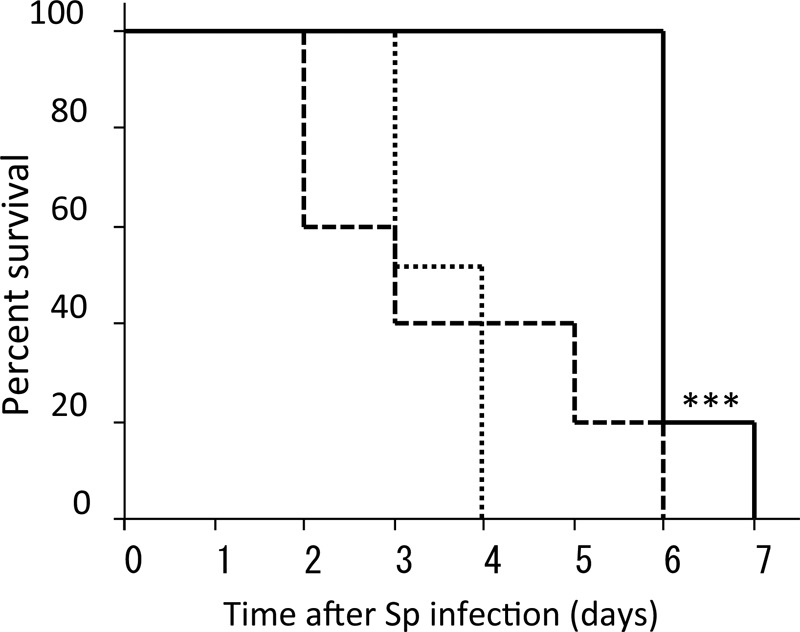

To confirm the importance of macrophages for protection against pneumococcal infection, we compared survival after S. pneumoniae infection in macrophage-depleted mice and mice with intact macrophages. All macrophage-depleted mice died within 6 days of infection; however, all intact mice survived at least 6 days after pneumococcal infection (P < 0.001, Fig. 9). Improved survival mediated by UT12 was not observed in macrophage-depleted mice (Fig. 9). Taken together, these data indicated that existing macrophages were essential for MCP-1-dependent enhancement of macrophage recruitment and UT12-mediated phagocytosis. Alveolar macrophages appeared to have a crucial role in initial bacterial killing within the lower respiratory tract (LRT), and UT12 augmented host innate immunity against severe pneumococcal pneumonia occurring after influenza infection.

Fig 9.

Percent survival of mice in a pneumococcal pneumonia model with or without clodronate liposome (C.L.) administration. Sp, S. pneumoniae. Kaplan-Meier curve with survival rates of mice (solid line, saline plus Sp [n = 10]; dashed line, C.L. plus Sp [n = 10]; dotted line, C.L. plus UT12 plus Sp [n = 6]). Statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test. The survival of Sp-infected mice without both C.L. and UT12 was longer than that of mice with C.L. pretreatment. ***, P < 0.001.

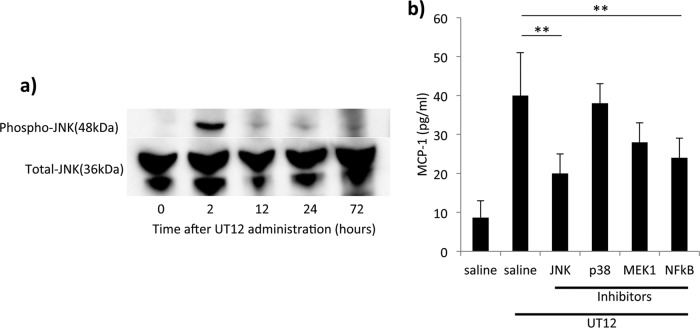

UT12 induced MCP-1 production via an NF-κB-and-JNK-dependent pathway.

To investigate the UT12-mediated TLR4 signaling pathways involved in the production of MCP-1, we examined the concentrations of activated NF-κB and the expression levels of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family proteins (JNK, p38, and MEK-1) in the lungs after UT12 administration. Compared with vehicle-treated mice, uninfected mice pretreated with UT12 had significantly increased levels of activated NF-κB (P < 0.001) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In addition, the level of phosphorylated JNK was also clearly increased at 2 h after UT12 administration (Fig. 10a), whereas the levels of phosphorylated p38 and MEK-1 were unchanged throughout the experiment (data not shown). To confirm the importance of the NF-κB-and-JNK-dependent pathway for UT12-mediated MCP-1 production, peritoneal macrophages were pretreated with specific MAPK inhibitors, i.e., SP600125 (a specific inhibitor of JNK), SB203580 (an inhibitor of p38), PD98059 (an inhibitor of MEK-1), and parthenolide (an inhibitor of NF-κB), for 30 min and then cotreated with UT12 for 4 h prior to the detection of MCP-1 in the supernatant. Pretreatment with SP600125 or parthenolide inhibited MCP-1 production, indicating that both JNK and NF-κB were involved in the production of MCP-1 in UT12-stimulated macrophages (Fig. 10b). These results suggested that activation of the JNK and NF-κB pathway was required for the promotion of MCP-1 production in UT12-treated macrophages.

Fig 10.

UT12-mediated MCP-1 production is required for the phosphorylation of both JNK and NF-κB. (a) Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in the lung after UT12 administration. (b) The levels of MCP-1 production 4 h after UT12 stimulation from the peritoneal macrophages pretreated with inhibitors of JNK, p38, MEK-1, and NF-κB. Values represent means ± SD. **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Influenza infection predisposes the host to secondary bacterial infection of the respiratory tract, which is a major cause of death in influenza-related disease, even if appropriate antibiotics are administered. Vaccination is the primary tool to prevent influenza infection, but its effectiveness is not 100%. Annual influenza epidemics result in an estimated 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness and 250,000 to 500,000 deaths every year.

The innate immune system recognizes and rapidly responds to microbial pathogens, providing the first line of host defense. It is becoming clear that induction of innate immunity may be useful for preventing bacterial infection. Indeed, Clement et al. reported that the stimulation of innate immunity by bacterial lysates induces the augmentation of antimicrobial polypeptides in lung-lining fluid and protects the lungs against lethal pneumococcal pneumonia (17). Moreover, providing insight into the specific mechanisms that regulate this response of the innate immune system, Yu et al. reported that intranasal pretreatment of mice with purified Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellin induces strong protection against Pseudomonas infection via TLR5 and markedly improves bacterial clearance (26). Therefore, TLR agonists are being developed as adjuvants for potent new vaccines to prevent or treat infectious diseases (27). For example, monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA), which is isolated from bacterial cell walls and detoxified, acts through TLR4 as an immune stimulator. TLR4 mediates LPS responsiveness and recognizes Gram-negative bacteria via the LPS moiety on the surface of these microorganisms. Some researchers have reported that MPL treatment promotes neutrophil recruitment to the infectious source and mediates protection against both lethal systemic bacterial infection and nasopharyngeal colonization (28, 29); however, little is known about whether the induction of innate immunity via TLR4 contributes to the protective immune response against bacterial infection. Therefore, in the current study, we used UT12, a new TLR4 agonistic monoclonal antibody, to address whether the promotion of innate host resistance through TLR4 mediates protection against secondary pneumococcal pneumonia following influenza virus infection. We found that in our coinfection model of influenza virus and pneumococcus, UT12 pretreatment significantly increased survival rates, attenuated the levels of proinflammatory cytokine production, and enhanced the clearance of bacteria. In a separate set of experiments in coinfected mice, we tested the effects of a single dose of UT12 prior to influenza virus or S. pneumoniae exposure. In these experiments, the increases of survival rates observed in coinfected mice with UT12 administration prior to both influenza virus and S. pneumoniae inoculation were lost, indicating that each prophylactic inoculation of UT12 may be relevant to its protective effects against severe lung injury induced by coinfection of influenza virus and S. pneumoniae. Thus, our data suggest that stimulation of the innate immune system protected against coinfection in this system.

Our previous study showed that in animals with prior influenza infection, a bacterial burden was detected as early as 48 h after secondary infection with S. pneumoniae, and extreme production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines was induced (cytokine storm), resulting in severe host tissue injury (10). In the present study, the viable S. pneumoniae count in the lungs of UT12-treated mice was significantly reduced compared with that in control mice 2 days after pneumococcal inoculation. In addition, cytokine storms induced by coinfection were suppressed in UT12-treated mice, suggesting that UT12 inhibited the growth of S. pneumoniae and attenuated the excessive host immune response. Thus, UT12-mediated reduction of host sensitivity against secondary pneumococcal exposure may inhibit the development of cytokine storms after influenza virus infection. These results are similar to those of a previous study that investigated the effects of the TLR4 agonist MPLA against postburn wound infection by P. aeruginosa (30).

We further examined changes in the immune cell population in the LRT to determine which cells were responsible for UT12-induced protection, since neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells are important cellular mediators of innate immune defense in severe pneumococcal pneumonia induced by coinfection with influenza virus. In particular, inflammatory macrophages respond rapidly to microbial stimuli by secreting cytokines and antimicrobial factors. In addition, they express the CCR2 chemokine receptor and traffic to sites of microbial infection in response to MCP-1 (also known as chemokine [C-C motif] ligand 2 [CCL2]) secretion. In murine models, monocyte recruitment mediated by the CCL2-CCR2 axis is essential for defense against several bacterial, protozoan, and fungal pathogens. Moreover, in pneumococcal studies, alveolar macrophages have also been shown to be essential for the initial clearance of pneumococci within the respiratory tract. Winter et al. demonstrated that MCP-1-dependent macrophage recruitment contributes to lung protective immunity against pneumococcal infection (31, 32). In the current study, the survival of pneumococcus-infected mice was similarly reduced by depletion of macrophages, and survival after pneumococcal pneumonia was not restored by UT12 administration in macrophage-depleted mice. Likewise, we showed that the accumulation of macrophages in the LRT and production of MCP-1 in the lungs were induced after UT12 administration. The disappearance of the benefit from UT12-mediated macrophage recruitment and MCP-1 production were observed in macrophage-depleted mice, indicating that resident macrophages may be responsible for producing MCP-1 after stimulation with UT12.

Our results also demonstrated that UT12 administration increased the phosphorylation of JNK and NF-κB. Moreover, JNK and NF-κB inhibitors significantly reduced MCP-1 production in macrophages, and UT12 exerted protective effects in C3H/HeN mice but not in C3H/HeJ mice, which have low responsiveness to TLR4 agonists. In addition, the UT12-mediated reduction of excessive inflammatory cytokine production induced by coinfection also disappeared in C3H/HeJ mice. These results indicate that sufficient innate immune activation against secondary pneumococcal infection via a TLR4-specific signaling pathway was induced by prophylactic UT12 treatment.

There were some limitations in this study. First, the importance of endotoxin tolerance induced by UT12 for the suppression of the cytokine storm was not demonstrated. The clearance of some pathogens is promoted during the LPS-tolerant state, despite attenuated cytokine production (33). The pneumococcal pore-forming toxin, pneumolysin, is also recognized by TLR4 (34, 35). Additional studies are required to determine the effects of UT12-mediated tolerance against the inflammation induced by S. pneumoniae and pneumolysin in particular. Second, we did not investigate the interaction between UT12 and other types of immune cells. For instance, we cannot exclude CD4-positive T cells or dendritic cells as sources of MCP-1 production, and we did not examine the phagocytic function of neutrophils. Therefore, additional cell deletion studies may be necessary to confirm which cells were the most important for UT12-induced MCP-1 production. However, our data demonstrate that macrophages play a crucial role in the activation of innate immunity against pneumococcal pneumonia induced by coinfection with influenza virus. Finally, we did not examine the signaling cross talk between TLRs, which regulates the host inflammatory reaction to bacterial infection (36, 37). Thus, in future experiments, we will investigate the role of other TLRs in UT12-induced signaling pathways.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that treatment with the TLR4 agonistic monoclonal antibody UT12 caused resistance to severe pneumonia, characterized by attenuation of systemic proinflammatory cytokine production and improved clearance of bacteria by enhanced recruitment of macrophages to sites of infection. Based on a limited case series and accumulated clinical experience, bacterial pneumonia following influenza virus infection appears to be more difficult to treat and has a high fatality rate. The ability of UT12 to improve survival, reduce inflammation, and enhance bacterial clearance makes it an attractive agent for potential application in patients that are at high risk of complications from influenza infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was partially supported by a grant from the Global Centers of Excellence Program, Nagasaki University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 May 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00010-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mathers CD, Boerma T, Ma Fat D. 2009. Global and regional causes of death. Br. Med. Bull. 92:7–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blyth CC, Webb SA, Kok J, Dwyer DE, van Hal SJ, Foo H, Ginn AN, Kesson AM, Seppelt I, Iredell JR; ANZIC Influenza Investigators; Microbiological Investigators COSI 2012. The impact of bacterial and viral co-infection in severe influenza. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses 7:168–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCullers JA. 2006. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:571–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brundage JF. 2006. Interactions between influenza and bacterial respiratory pathogens: implications for pandemic preparedness. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6:303–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. 2008. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 198:962–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Palacios G, Hornig M, Cisterna D, Savji N, Bussetti AV, Kapoor V, Hui J, Tokarz R, Briese T, Baumeister E, Lipkin WI. 2009. Streptococcus pneumoniae coinfection is correlated with the severity of H1N1 pandemic influenza. PLoS One 4:e8540. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2012. Severe coinfection with seasonal influenza A (H3N2) virus and Staphylococcus aureus—Maryland, February-March 2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 61:289–291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cilloniz C, Ewig S, Menendez R, Ferrer M, Polverino E, Reyes S, Gabarrus A, Marcos MA, Cordoba J, Mensa J, Torres A. 2012. Bacterial co-infection with H1N1 infection in patients admitted with community acquired pneumonia. J. Infect. 65:223–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aebi T, Weisser M, Bucher E, Hirsch HH, Marsch S, Siegemund M. 2010. Co-infection of influenza B and streptococci causing severe pneumonia and septic shock in healthy women. BMC Infect. Dis. 10:308. 10.1186/1471-2334-10-308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seki M, Yanagihara K, Higashiyama Y, Fukuda Y, Kaneko Y, Ohno H, Miyazaki Y, Hirakata Y, Tomono K, Kadota J, Tashiro T, Kohno S. 2004. Immunokinetics in severe pneumonia due to influenza virus and bacteria coinfection in mice. Eur. Respir. J. 24:143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boivin N, Sergerie Y, Rivest S, Boivin G. 2008. Effect of pretreatment with toll-like receptor agonists in a mouse model of herpes simplex virus type 1 encephalitis. J. Infect. Dis. 198:664–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin YS, Huang LD, Lin CH, Huang PH, Chen YJ, Wong FH, Lin CC, Fu SL. 2011. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of a synthetic glycolipid as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activator. J. Biol. Chem. 286:43782–43792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang Y, Luo F, Cai Y, Liu N, Wang L, Xu D, Chu Y. 2011. TLR1/TLR2 agonist induces tumor regression by reciprocal modulation of effector and regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 186:1963–1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jarchum I, Liu M, Lipuma L, Pamer EG. 2011. Toll-like receptor 5 stimulation protects mice from acute Clostridium difficile colitis. Infect. Immun. 79:1498–1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ohta S, Bahrun U, Shimazu R, Matsushita H, Fukudome K, Kimoto M. 2006. Induction of long-term lipopolysaccharide tolerance by an agonistic monoclonal antibody to the toll-like receptor 4/MD-2 complex. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13:1131–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. St Paul M, Mallick AI, Read LR, Villanueva AI, Parvizi P, Abdul-Careem MF, Nagy E, Sharif S. 2012. Prophylactic treatment with Toll-like receptor ligands enhances host immunity to avian influenza virus in chickens. Vaccine 30:4524–4531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clement CG, Evans SE, Evans CM, Hawke D, Kobayashi R, Reynolds PR, Moghaddam SJ, Scott BL, Melicoff E, Adachi R, Dickey BF, Tuvim MJ. 2008. Stimulation of lung innate immunity protects against lethal pneumococcal pneumonia in mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177:1322–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kosai K, Seki M, Tanaka A, Morinaga Y, Imamura Y, Izumikawa K, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, Yanagihara K, Tomono K, Kohno S. 2011. Increase of apoptosis in a murine model for severe pneumococcal pneumonia during influenza A virus infection. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 64:451–457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yanagihara K, Seki M, Cheng PW. 2001. Lipopolysaccharide induces mucus cell metaplasia in mouse lung. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 24:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jordan MB, van Rooijen N, Izui S, Kappler J, Marrack P. 2003. Liposomal clodronate as a novel agent for treating autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a mouse model. Blood 101:594–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matsuda N, Hattori Y. 2006. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): molecular pathophysiology and gene therapy. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 101:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Walsh KB, Teijaro JR, Wilker PR, Jatzek A, Fremgen DM, Das SC, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Shinya K, Suresh M, Kawaoka Y, Rosen H, Oldstone MB. 2011. Suppression of cytokine storm with a sphingosine analog provides protection against pathogenic influenza virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:12018–12023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu SF, Malik AB. 2006. NF-kappa B activation as a pathological mechanism of septic shock and inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 290:L622–L645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chao J, Blanco G, Wood JG, Gonzalez NC. 2011. Renin released from mast cells activated by circulating MCP-1 initiates the microvascular phase of the systemic inflammation of alveolar hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 301:H2264–H2270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Rooijen N, van Kesteren-Hendrikx E. 2002. Clodronate liposomes: perspectives in research and therapeutics. J. Liposome Res. 12:81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu FS, Cornicelli MD, Kovach MA, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Kumar A, Gao N, Yoon SG, Gallo RL, Standiford TJ. 2010. Flagellin stimulates protective lung mucosal immunity: role of cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide. J. Immunol. 185:1142–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kanzler H, Barrat FJ, Hessel EM, Coffman RL. 2007. Therapeutic targeting of innate immunity with Toll-like receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat. Med. 13:552–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hirano T, Kodama S, Kawano T, Maeda K, Suzuki M. 2011. Monophosphoryl lipid A induced innate immune responses via TLR4 to enhance clearance of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis from the nasopharynx in mice. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 63:407–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Romero CD, Varma TK, Hobbs JB, Reyes A, Driver B, Sherwood ER. 2011. The Toll-like receptor 4 agonist monophosphoryl lipid A augments innate host resistance to systemic bacterial infection. Infect. Immun. 79:3576–3587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akira S, Sato S. 2003. Toll-like receptors and their signaling mechanisms. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 35:555–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winter C, Herbold W, Maus R, Langer F, Briles DE, Paton JC, Welte T, Maus UA. 2009. Important role for CC chemokine ligand 2-dependent lung mononuclear phagocyte recruitment to inhibit sepsis in mice infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Immunol. 182:4931–4937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Winter C, Taut K, Srivastava M, Langer F, Mack M, Briles DE, Paton JC, Maus R, Welte T, Gunn MD, Maus UA. 2007. Lung-specific overexpression of CC chemokine ligand (CCL) 2 enhances the host defense to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in mice: role of the CCL2-CCR2 axis. J. Immunol. 178:5828–5838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lehner MD, Ittner J, Bundschuh DS, van Rooijen N, Wendel A, Hartung T. 2001. Improved innate immunity of endotoxin-tolerant mice increases resistance to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection despite attenuated cytokine response. Infect. Immun. 69:463–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dessing MC, Hirst RA, de Vos AF, van der Poll T. 2009. Role of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in pulmonary inflammation and injury induced by pneumolysin in mice. PLoS One 4:e7993. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Malley R, Henneke P, Morse SC, Cieslewicz MJ, Lipsitch M, Thompson CM, Kurt-Jones E, Paton JC, Wessels MR, Golenbock DT. 2003. Recognition of pneumolysin by Toll-like receptor 4 confers resistance to pneumococcal infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1966–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Nardo D, De Nardo CM, Nguyen T, Hamilton JA, Scholz GM. 2009. Signaling crosstalk during sequential TLR4 and TLR9 activation amplifies the inflammatory response of mouse macrophages. J. Immunol. 183:8110–8118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lim JH, Ha U, Sakai A, Woo CH, Kweon SM, Xu H, Li JD. 2008. Streptococcus pneumoniae synergizes with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae to induce inflammation via upregulating TLR2. BMC Immunol. 9:40. 10.1186/1471-2172-9-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.