Abstract

HLA class I alleles have been shown to have differential impacts on the viral load and the outcome of HIV-1 disease progression. In this study, HLA class I types from residents of China with acute HIV-1 infection, diagnosed between 2006 and 2011, were identified and the association between expression of individual HLA alleles and the level of the set point viral load was analyzed. A lower level of set point viral load was found to be associated with the Bw4 homozygote on HLA-B alleles. B*44 and B*57 alleles have also been found to be associated with lower set point viral load. The set point viral load of B*44-positive individuals homozygous for Bw4 was significantly lower than that of B*44-negative individuals homozygous for Bw4 (P = 0.030). The CD4 count declined to <350 in fewer B*44-positive individuals than B*44-negative individuals (X2 = 7.295, P = 0.026). B*44-positive individuals had a lower magnitude of p24 pool-specific T cell responses than B*44-negative individuals homozygous for Bw4, though this was not statistically significant. The p24 pool-specific T cell responses were also inversely correlated with lower viral load (rs = −0.88, P = 0.033). Six peptides within p24 were recognized to induce the specific-T cell response in B*44-positive individuals, and the peptide breadth of response was same as that in B*44-negative individuals homozygous for Bw4, but the median magnitude of specific-T cell responses to the recognized peptides in B*44-positive individuals was lower than that in B*44-negative individuals homozygous for Bw4 (P = 0.049). These findings imply that weak p24-specific CD8+ T cell responses might play an important role in the control of HIV viremia in B*44 allele-positive individuals. Such studies might contribute to the development of future therapeutic strategies that take into account the genetic background of the patients.

INTRODUCTION

Many host genetic determinants influence the progression of HIV-1/AIDS (1–4). One of these is the HLA system. This system includes the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and has been the focus of a great deal of research due to its major biological function, which involves presenting foreign peptides to the immune system. Class I HLA molecules are the most prominent with respect to disease progression, indicating that the effects of HLA class I molecules on the HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses play a major role in controlling viremia (5–6). In order to design globally effective HIV-1 vaccines that can be used to induce CTL responses restricted by HLA class I alleles, it is crucial to determine the differential abilities of different HLA class I alleles. This will allow physicians to control viremia in different parts of the world. Only two variants, HLA-B*27 and -B*57, have consistently been associated with lower viral load and better clinical outcomes (7–10). However, the effects of individual HLA alleles, haplotypes, and supertypes with reported impacts on HIV-1 viral load are not always clear because their distributions and patterns of linkage disequilibrium often differ from one population to another (11, 12). HLA-B*44 has been reported to have promising results in the control of viremia during two distinct phases of primary HIV-1 infection in individuals in sub-Saharan Africa (13) and in individuals in the United States with long-term HIV-1 infection (14). Because people of Asian descent have HLA class I profiles distinct from those of people of African descent, known associations between HLA-B*44 expression and control of HIV replication may be applicable only to a limited geographical area. In order to design globally effective HIV-1 vaccines that aim to induce CD8+ T cell responses restricted by HLA class I alleles, it is crucial to identify the differential abilities of HLA class I alleles to control viremia in different parts of the world, including China. In the present study, we found that HLA-B*44 could suppress HIV replication in acute HIV infections in a population of men who have sex with men (MSM).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

A total of 126 Chinese subjects who had been diagnosed with acute HIV-1 infection (AHI) between 2006 and 2011 were enrolled in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and Beijing Youan Hospital of Capital Medical University approved the study (no. 20061109V1). Follow-up of the participants was done once every 2 to 3 months, before their condition became classified as acute HIV-1 infection. After the transition to the acute phase of HIV-1 infection, follow-up was done at 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 weeks and then once every 3 months for the remainder of the year. All participants were young or middle-aged adult men, and each had acquired HIV-1 infection through sexual intercourse with another man. Acute HIV-1 infection was identified in all subjects via documenting the level of HIV-1 RNA using the pooled nucleic acid amplification test, the negative or indeterminate HIV-1 antibody test, and Western blot analysis (15). HIV-1 seroconversion was documented if there was any interval of less than 24 weeks between a negative and a positive HIV-1 antibody test or by an incomplete Western blot assay followed by a complete Western blot assay. The interval after transition to HIV-1 infection was calculated using laboratory values as described below, and those results were combined with the epidemiological data. The date of infection was defined as the date of the incomplete Western blot assay minus 1 month, using the date of a primary symptomatic infection minus 15 days, a midpoint date between the two tests, or the date of a negative HIV-1 antibody test or an indeterminate and a positive HIV-1 RNA test minus 15 days from the test date (16–18).

HLA class I allele typing.

Genotypes, including HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1, were determined by sequence-specific primer (SSP)-PCR (performed at the Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford University) or sequence-based typing (SBT)-PCR (performed at the HuaDa Gene Research Institute, Beijing, China). Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using a QIAamp DNA Blood MiniKit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Among the 126 AHI cases, 85 were evaluated using low-resolution (2-digit) HLA genotyping and 41 were evaluated using high-resolution (4-digit) HLA genotyping. Two-digit HLA was used for data analysis. HLA linkage disequilibrium was also analyzed (http://www.HIV.lanl.gov/content/immunology/hla/hla_linkage.html/). The Bw4 and Bw6 motifs were categorized using SSP-PCR. The Hardy-Weinberg status of the distribution of the HLA-A, -B, and -C loci was assessed using PopGen 3.2 software, and P > 0.05 was considered indicative of compliance with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. In addition, the HLA genotyping of 400 HIV-negative healthy persons was also determined by SBT-PCR.

Viral load and viral set point.

All measurements from clinic visits in which subsequent viral loads did not appear to be at the steady state were excluded for the study participants who had multiple clinical visits. Specifically, data were excluded whenever the intervisit viral load variation exceeded 3-fold (0.5 log10) copies per ml of plasma, as described by Fellay et al. (19). Individuals with less than two steady-state viral loads were excluded from the study. The set point viral load was defined as the stable HIV-1 RNA load approximately 5 to 12 months after acute HIV-1 infection. Viral load data were analyzed after log10 transformation.

ELISPOT assay.

Thawing PBMCs were pulsed for T cell immune responses with p17, p24, p15, and nef peptide pools. These synthetic peptides were based on the HIV-1 CRF01_A/E CM240 sequence and overlapped by 10 amino acids with a length of 18 amino acids. HIV-specific T cell responses were measured by quantification of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) release in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay. Anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (MAb) 1-D1K (Mabtech AB, Nacka, Sweden), biotinylated anti-IFN-γ MAb 7-B6-1 (Mabtech AB), and streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Mabtech AB) were used. IFN-γ-producing cells were counted using an ELISPOT reader (Antai Yongxin Medical Technology, Beijing, China), and results were expressed as numbers of spot-forming cells (SFC) per million PBMCs. Only responses above 50 SFC/million PBMCs and with 3 times more spot-forming cells than the negative control were considered positive.

Statistical analysis.

Quantitative variables were described using means and standard deviations (SD) in cases in which the underlying distribution was normal. The median was used for variables without normal distribution. Differences were analyzed using the Student t test for independent samples or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were described using proportions and percentages. Differences between proportions were analyzed with the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Differences were considered statistically significant at a P of <0.05 for two-tailed tests. General linear model analysis was performed for all variables hypothesized to be the influential factors for the events under study. The association of the Bw4 and Bw6 genotypes with survival time and the time required for CD4 decline to less than 350/μl from the estimated date of infection were assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and the log rank test. The q value is the P value statistical correction for multiple comparisons of the same data performed using the method described by Benjamini and Hochberg (20). This method is used to control the false discovery rate (FDR) and to determine whether the HLA allele was associated with the viral set point. Taking into consideration the cooperative additive effects between HLA alleles, the less stringent criterion of q < 0.2 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0, and Graph Pad Prism 5 software was used to graph the results.

RESULTS

HLA allele polymorphism and the haplotypes in a cohort of homosexual men.

In this study, we aimed to identify HLA class I alleles that are associated with a lower viral set point in men who have sex with men (MSM) and to investigate the impact of individual HLA class I allele expression on the progression of HIV-1 disease at the population level. The distribution of the HLA-A, -B, and -C alleles in the MSM population did not deviate from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.05, q < 0.05). The total number of HLA class I alleles with over 2% frequency in this population was 43 (HLA-A, 11; HLA-B, 21; HLA-C, 11 [n = 126]). This is comparable to that observed in European-Americans (total, 46; HLA-A, 14; HLA-B, 19; HLA-C, 13) (21). Over 20% of the population express one of these HLA alleles located at the HLA-A, -B, and -C loci, such as A*02, A*11, A*24, B*13, B*15, B*40, Cw*01, Cw*03, Cw*06, and Cw*07, and over 50% of the population express the A*02 allele.

In the MSM population, the linkage disequilibrium haplotypes between two of the HLA loci were A*30B*13, A*33B*58, B*58Cw*03, A*30Cw*06, B*13Cw*06, B*44Cw*05, B*46Cw*01, B*51Cw*14, and B*52Cw*12 and occurred in the population at frequencies of 11.6%, 5.8%, 7.4%, 11.6%, 14.1%, 5.0%, 13.2%, 4.1%, and 5.8%, respectively. The linkage haplotypes among the three loci were A*30B*13Cw*06 and A*33B*58C*03 and occurred at frequencies of 11.6% and 5.8%, respectively.

The HLA-A, -B, and -C allele distribution in the AHI MSM cohort was compared with that in 400 healthy persons without HIV infection. The population frequencies of HLA-B*44, -B*57, and -B*58 in the 400 HIV-negative healthy people were 9.8%, 3.33%, and 7.44%, respectively. This was consistent with the population frequencies in the AHI MSM cohort, which were 10.1%, 3.17%, and 7.14%, respectively. Similarly, the frequencies of the other HLA alleles in these two populations were not statistically significantly different (P > 0.05, q > 0.2).

Impact of host HLA class I alleles on the set point viral load.

After the acute phase of HIV-1 infection, the viral load usually reaches a steady state, commonly known as the set point. Set point viral loads are reflections of the equilibrium between the HIV-1 virus level and the immune response and are an important predictor of HIV-1 disease progression (22). Lower viral load set points predict delayed onset of AIDS and better clinical outcomes. The viral set point levels that occurred in the presence of individual class I alleles were compared to the levels that occurred in the absence of these alleles in order to identify the HLA class I alleles that are associated with lower viral load set points. We found that the HIV-1 patients who expressed B*44 (Table 1) (n = 13) and B*57 (n = 4) had significantly lower set point viral loads than those who did not express B*44 (median, 3.41 versus 4.35, P = 0.0017, q = 0.041) and B*57 (median, 3.35 versus 4.31, P = 0.010, q = 0.120). The median of the set point viral load in B*58-positive individuals (n = 9) was lower than that of B*58-negative individuals, and the P value was 0.032, but the q value was larger than 0.20. Individuals who expressed reported protective alleles, such as B*27 and B*51, and other alleles, such as A*31, A*32, B*52, and B*67, did not have significantly lower set point viral loads than those who did not (all P > 0.05, q > 0.20) (Table 1). No clear association between HLA-C alleles and control of HIV-1 viremia was observed in this population.

Table 1.

Association between the level of the set point viral load and expression of individual HLA class I alleles and haplotypesa

| HLA allele | Presence of indicated allele |

Absence of indicated allele |

P valueb | q value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | VL | No. of cases | VL | |||

| A*01 | 11 | 4.42 | 115 | 4.34 | NS | NS |

| A*02 | 68 | 4.48 | 58 | 4.31 | NS | NS |

| A*03 | 12 | 4.05 | 114 | 4.38 | NS | NS |

| A*11 | 48 | 4.36 | 78 | 4.37 | NS | NS |

| A*24 | 29 | 4.40 | 97 | 4.34 | NS | NS |

| A*26 | 10 | 4.39 | 116 | 4.37 | NS | NS |

| A*30 | 18 | 4.15 | 117 | 4.29 | NS | NS |

| A*31 | 9 | 4.06 | 119 | 4.29 | NS | NS |

| A*32 | 7 | 3.89 | 111 | 4.30 | NS | NS |

| A*33 | 15 | 4.45 | 123 | 4.37 | NS | NS |

| A*68 | 3 | 4.30 | 118 | 4.37 | NS | NS |

| B*07 | 8 | 4.28 | 122 | 4.38 | NS | NS |

| B*08 | 4 | 4.71 | 101 | 4.35 | NS | NS |

| B*13 | 25 | 4.17 | 95 | 4.30 | NS | NS |

| B*15 | 31 | 4.67 | 120 | 4.22 | NS | NS |

| B*27 | 6 | 4.36 | 113 | 4.27 | NS | NS |

| B*35 | 13 | 4.30 | 121 | 4.26 | NS | NS |

| B*37 | 5 | 4.37 | 117 | 4.28 | NS | NS |

| B*38 | 9 | 4.66 | 122 | 4.56 | NS | NS |

| B*39 | 4 | 4.30 | 86 | 4.49 | NS | NS |

| B*40 | 40 | 4.40 | 113 | 4.22 | NS | NS |

| B*44 | 13 | 3.41 | 109 | 4.35 | 0.0017 | 0.041 |

| B*46 | 17 | 4.61 | 115 | 4.56 | NS | NS |

| B*48 | 11 | 4.47 | 123 | 4.67 | NS | NS |

| B*50 | 3 | 5.47 | 116 | 4.36 | NS | NS |

| B*51 | 10 | 4.36 | 117 | 4.37 | NS | NS |

| B*52 | 9 | 3.68 | 120 | 4.38 | NS | NS |

| B*54 | 6 | 4.66 | 119 | 4.39 | NS | NS |

| B*55 | 7 | 4.76 | 122 | 4.25 | NS | NS |

| B*57 | 4 | 3.35 | 117 | 4.31 | 0.010 | 0.120 |

| B*58 | 9 | 3.75 | 122 | 4.32 | 0.042 | 0.336 |

| B*67 | 4 | 3.90 | 94 | 4.35 | NS | NS |

| Cw*01 | 32 | 4.67 | 123 | 4.51 | NS | NS |

| Cw*02 | 3 | 4.41 | 83 | 4.23 | NS | NS |

| Cw*03 | 43 | 4.35 | 114 | 4.40 | NS | NS |

| Cw*04 | 12 | 4.38 | 119 | 4.65 | NS | NS |

| Cw*05 | 7 | 3.94 | 96 | 4.34 | NS | NS |

| Cw*06 | 30 | 4.16 | 82 | 4.33 | NS | NS |

| Cw*07 | 44 | 4.47 | 101 | 4.25 | NS | NS |

| Cw*08 | 25 | 4.46 | 113 | 4.19 | NS | NS |

| Cw*12 | 13 | 4.30 | 120 | 4.65 | NS | NS |

| Cw*14 | 6 | 3.84 | 119 | 4.37 | NS | NS |

| Cw*15 | 7 | 4.31 | 119 | 4.56 | NS | NS |

| A*30B*13Cw*06 | 15 | 4.14 | 111 | 4.30 | NS | NS |

| A*33B*58Cw*03 | 7 | 3.98 | 119 | 4.28 | NS | NS |

Viral load (VL) data represent median set points. NS, not significant.

P values were determined by the Mann-Whitney U test.

We found no advantage or disadvantage with respect to the control of viremia in individuals expressing the haplotypes A*30B*13, A*33B*58, B*58Cw*03, A*30Cw*06, B*13Cw*06, B*44Cw*05, B*46Cw*01, B*51Cw*14, B*52Cw*12, A*30B*13Cw*06, and A*33B*58Cw*03 compared to patients without these haplotypes who had comparable levels of set point viral loads (all P > 0.05, q > 0.02).

Association between lower set point viral load and a slower decline in CD4 count and Bw4 homozygote on the HLA-B locus.

HLA-B alleles can be divided into two mutually exclusive groups based on the expression of the molecular motifs Bw4 and Bw6. In the individuals with acute HIV-1, the Bw4 homozygote, the Bw4 heterozygote, and the Bw6 homozygote were found to be expressed on the HLA-B alleles in 25, 54, and 47 patients, respectively. The association between the set point viral load and the Bw4 homozygote was then investigated. The set point viral load was found to be lowest in the Bw4 homozygote (3.57 ± 0.70) group and was significantly lower than in individuals who were heterozygous for Bw4 (4.24 ± 0.85) or homozygous for Bw6 (4.56 ± 0.63) (general linear model, F = 7.928, P = 0.001; multiple comparisons, all P < 0.01). The Bw4-homozygous individuals who expressed B*44, B*57, and B*58 alleles were excluded, and the remaining individuals were analyzed in order to avoid the confounding effects of these alleles due to carrying the Bw4 motif. After correction for the potentially confounding effects of B*44, B*57, and B*58, the Bw4 homozygote was still associated with a lower set point viral load than the Bw4 heterozygote and the Bw6 homozygote (P = 0.009 overall; P = 0.0008 for Bw4/4 [n = 13] versus Bw6/6 [n = 47]; P = 0.038 for Bw4/4 versus Bw4/6 [n = 43]).These findings showed that profound suppression of HIV-1 viremia was closely associated with the Bw4 homozygosity that HLA-B alleles confer and that this was independent of the presence or absence of B*44 and B*57 alleles.

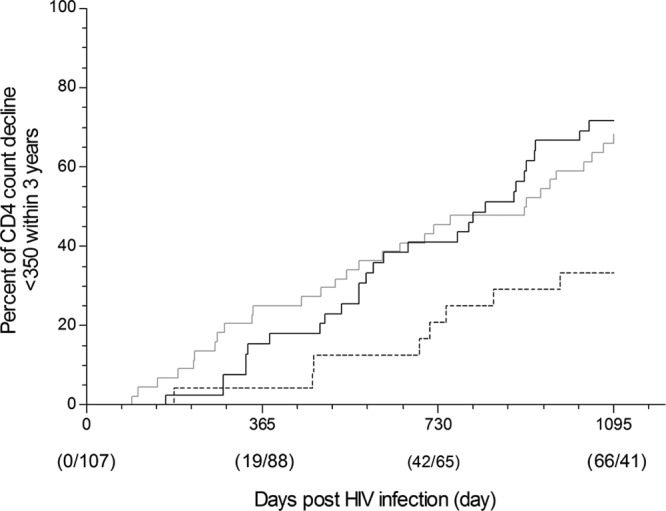

During the ongoing follow-up, 107 patients were followed for more than 3 years and 19 patients were not. There were 66 (61.7%) patients whose CD4 count rapidly declined to less than 350 and 41 patients whose CD4 count was still over 350 within 3 years after HIV-1 infection. Moreover, 20 patients received highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) within 3 years after acute HIV infection and the remaining 87 patients did not receive HAART. It has been reported that Bw4 homozygous individuals may have an intrinsic advantage that delays the progression of HIV-1-associated disease (13). Therefore, we investigated whether the Bw4 homozygote was predictive of the ability to maintain a normal CD4 count in this high-risk MSM population. During follow-up, the CD4 count was less than 350 for 3 consecutive measurements, and the first date of measurement was set as the time when the CD4 count declined to less than 350. After that time, the CD4 count never exceeded 350 before initiation of HAART. As shown in Fig. 1, Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrate that the Bw4 homozygote confers a significant advantage over the Bw4 heterozygote (X2 = 7.65, P = 0.006) and especially over the Bw6 homozygote (X2 = 8.94, P = 0.003) with respect to the timing of the decline in CD4 count (X2 = 9.47, P = 0.009, for overall strata). We also found the Bw4 homozygote to have a lower risk of a decline in the CD4 count than the other two genotypes (Table 2).

Fig 1.

Time to decline of CD4 count to <350 within 3 years. Kaplan-Meier survival curves are shown for time to decline of CD4 count to less than 350 post-HIV-1 infection according to HLA-Bw4 homozygote (dashed line [n = 23]), HLA-Bw4/Bw6 heterozygote (gray solid line [n = 44]), or HLA-Bw6 homozygote (black solid line [n = 40]) results among 107 study participants. A total of 19 participants were not followed up to 3 years and were excluded from the calculations. For overall strata, X2 = 9.47, P = 0.009; for Bw4/4 versus Bw4/6, X2 = 7.65, P = 0.006; for Bw4/4 versus Bw6/6, X2 = 8.94, P = 0.003 (Log rank test).

Table 2.

HLA-B Bw4/4 motifs presenting low relative risk of CD4 count decline to <350 within 3 years after HIV-1 infectiona

| Motif comparison | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bw4/4 vs Bw4/6 + Bw6/6 | 0.185 | 0.068 to 0.506 | 0.001 |

| Bw4/4 vs Bw4/6 | 0.204 | 0.069 to 0.608 | 0.004 |

| Bw4/4 vs Bw6/6 | 0.166 | 0.054 to 0.512 | 0.002 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Association between the B*44 allele and lower set point viral load.

Among the 25 individuals who expressed the Bw4 homozygote, 8 expressed the B*44 allele, and of the 54 individuals heterozygous for Bw4, 5 expressed the B*44 allele. The B*44 allele occurred significantly more frequently in Bw4-homozygous individuals than in Bw4-heterozygous individuals (odds ratio = 4.612; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.326 to 16.04 [Fisher's exact test, P = 0.0199]). Because B*44 confers Bw4 specificity, we further analyzed whether the beneficial role of Bw4 homozygosity was influenced by the B*44 allele. Individuals homozygous for Bw4 were divided into B*44-positive and B*44-negative groups, and the differences in set point viral load were compared. The set point viral load in B*44-positive individuals (n = 8) was significantly lower than that in B*44-negative individuals (n = 17) (median, 3.22 versus 3.96 [P = 0.030, Mann-Whitney U test]). These data further imply that the B*44 allele has a beneficial effect on the control of HIV-1 viremia.

Among the 13 B*44-positive individuals, the CD4 count was still >350 in 8 subjects and had declined to <350 after 3 years of acute HIV infection in 3 subjects; 2 subjects were not followed up to 3 years. Among the 41 patients whose CD4 counts were >350 after 3 years of acute HIV infection, 8 expressed the B*44 allele, 5 expressed the B*57 or B*58 allele, and 28 did not express the B*44, B*57, or B*58 allele. Among the 66 patients whose CD4 counts declined to <350 after 3 years of acute HIV infection, 3 patients expressed the B*44 allele, 5 expressed the B*57 or B*58 allele, and 58 did not express the B*44, B*57, or B*58 allele. The difference was found to be significant by Fisher's exact test (χ2 = 7.295, P = 0.026). These data indicate that there were far fewer B*44-positive individuals among patients whose CD4 counts declined to <350 than among patients who did not express the B*44 allele, suggesting that the B*44 allele may play a role in preventing or slowing CD4 decline.

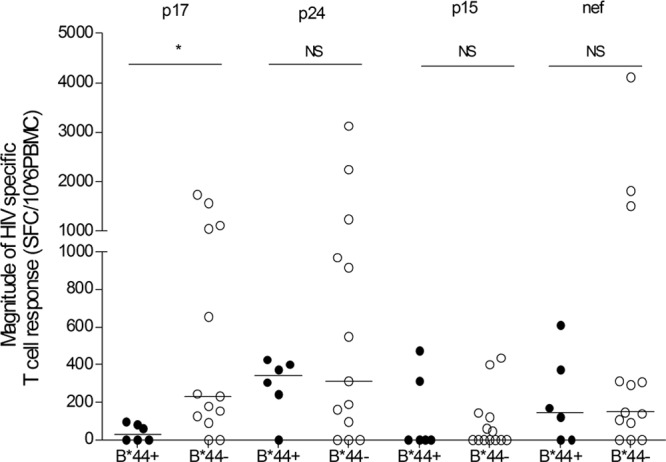

Differences in p17-, p24-, p15-, and nef-specific T cell responses and the association between viral load and p24-specific T cell responses elicited in B*44-positive and B*44-negative individuals.

As described above, the B*44 allele was associated with a lower set point viral load, but the association between the B*44 allele-positive individuals and the HIV-specific T cell responses was not clear. To further reveal this association, 6 B*44-positive individuals who were Bw4 homozygous or heterozygous and 13 B*44-negative individuals who were Bw4 homozygous, all of whom were infected with CRF01_A/E, were enrolled in a subsequent study. PBMCs were isolated from whole blood at 5 to 12 months after acute HIV-1 infection. The IFN-γELISPOT assay was performed to induce HIV-specific T cell responses to p17, p24, p15, and nef peptide pools. We found that HIV-specific T cell responses to the p17 pool elicited in B*44-positive individuals were significantly weaker than those elicited in B*44-negative individuals (P = 0.011, Mann-Whitney U test) (Fig. 2). HIV-specific T cell responses to the p24 and nef pools elicited in B*44-positive individuals were weaker, though not statistically significantly so, than those of B*44-negative individuals (P > 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test) (Fig. 2), and HIV-specific T cell responses to the p15 pool were comparable in B*44-positive and B*44-negative individuals. At the level of the HLA allele, a lower viral load was inversely associated with higher HIV-specific T cell responses to the p24 pool within the B*44 allele (rs = −0.88, P = 0.033); however, no association was observed with the p17, p15, or nef pools. Likewise, the trend toward lower viral load and higher HIV-specific T cell responses to the p24 pool was observed within the non-B*44 alleles homozygous for Bw4 (rs = −0.34, P = 0.251). The correlation (trend) between HIV-specific immune responses and plasma viral load, particularly with respect to the p24 pool, suggests that p24-specific T-cell responses might play an important role in the control of viremia.

Fig 2.

Differences of HIV-specific T cell responses of B*44-positive individuals and B*44-negative individuals. p17, p24, p15, and nef data represent p17, p24, p15, and nef pools with a peptide length of 18 amino acids overlapped by 10 amino acids. B*44+, B*44-positive individuals with Bw4 homozygote or heterozygote (n = 6); B*44−, B*44-negative individuals with Bw4 homozygote (n = 13); *, P < 0.05; NS, not significant.

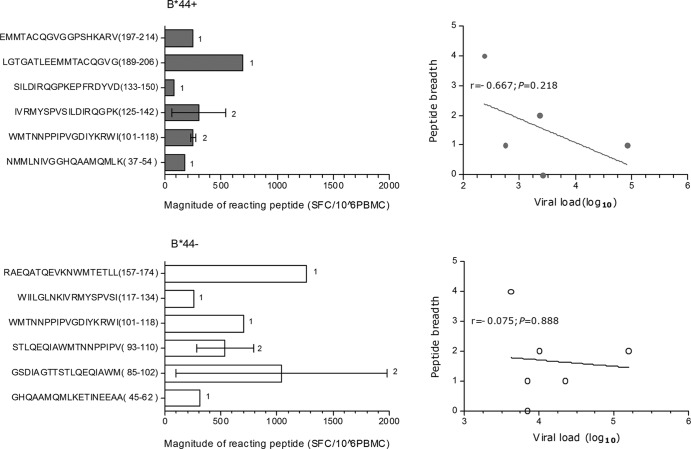

Due to the relationship between the p24-specific T cell responses and viral load described above, the breadth and magnitude of T cell responses to individual peptides within p24 were further examined in 5 B*44-positive individuals who were Bw4 homozygous or heterozygous and 6 B*44-negative individuals who were homozygous for Bw4. Of the 27 peptides within p24, 6 peptides were recognized by the sample of at least one subject in both the B*44-positive and B*44-negative groups. An inverse trend was found between the peptide breadth of response and the level of the viral load in B*44-positive individuals (rs = −0.667, P = 0.218) (Fig. 3), but there was no trend found with respect to a correspondence between the peptide breadth of response and the level of viral load in B*44-negative individuals (rs = −0.075, P = 0.888) (Fig. 3). The median magnitude of recognized peptides was 238 spot-forming cells (SFC)/106 PBMCs (range, 80 to 690 SFC/106 PBMCs) in B*44-positive individuals and was significantly lower than that in B*44-negative individuals (505 SFC/106 PBMCs [range, 95 to 1,980 SFC/106 PBMCs]; P = 0.049, Mann-Whitney U test). Among the 5 B*44-positive individuals, there were 2 subjects who responded to peptide WMTNNPPIPVGDIYKRWI (101 to 118) or IVRMYSPVSILDIRQGPK (125 to 142) and 1 subject who responded to one of the other 4 peptides (Fig. 3). Only peptide WMTNNPPIPVGDIYKRWI (101 to 118) was also observed to induce a specific T cell response in one of the six B*44-negative individuals (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

(Left) Comparison of the magnitudes of reacting peptide-induced specific-T cell responses. (Right) Correlation between the breadth of the response of reacting peptides and the level of viral load. B*44+, B*44-positive individuals (n = 5; upper panels); B*44−, B*44-negative individuals (n = 6; lower panels); 1, one subject responded to the peptide; 2, two subjects responded to the peptide.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the set point viral load ranged from 2.0 to 6.0 logs among individuals. The patients whose CD4 counts were still over 350 after 3 years of HIV infection had significantly lower levels of set point viral load than other patients whose CD4 counts declined to less than 350 within 1 year of HIV infection (P < 0.01, data not shown). Of the 126 patients diagnosed with AHIs, 74 individuals were infected with CRF01_A/E, 37 with -B, 13 with -B/C, and 2 with other viral subtypes. The levels of set point viral load and the rates of CD4 decline were not different among the individuals with different subtypes (P > 0.05, data not shown). Since set point viral load is an important predictor of the progression of HIV-1-related disease and because host genetic determinants may influence the progression of HIV-1/AIDS, we analyzed the differences in HLA-I alleles that might influence variations in the viral set point and in the progression of disease (22, 23).

Data in the current study have detailed the distribution of HLA-I alleles, including reported protective alleles such as B*27 and B*57, in this MSM population; however, no allele frequency exceeded 5%. We found that the levels of set point viral load in B*57-positive individuals were significantly lower than those of B*57-negative individuals in this study (P = 0.010, q = 0.120) (Table 1). This result is supported by previous studies in Western populations in which the B*57 allele was associated with lower levels of set point viral load (24–26). Additionally, the levels of set point viral load in B*58-positive individuals were lower than those of B*58-negative individuals, but this was not statistically significant since the q value was greater than 0.20 (P = 0.042, q = 0.336) (Table 1). In contrast to studies performed on Caucasian populations, the B*27 allele in this population was not associated with lower set point viral loads. It has been documented that HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cell responses restricted to HLA-B*57 can confer protection early during acute infection and delay the progression to AIDS (10, 27). However, B*27-restricted T-cell recognition can also target the late phase of HIV-1 infection (27). This may account for the association between the B*57 allele and the lower set point viral load and the lack of any such association between B*27 and the set point viral load.

Flores-Villanueva et al. reported that control of HIV-1 viremia and protection from AIDS are associated with Bw4 homozygosity (13). We also observed that those with Bw4 homozygosity had an advantage over those with Bw4 heterozygosity and Bw6 homozygosity, having both a lower set point viral load and a slower decline in CD4 count within 3 years of HIV-1 infection. However, in this study, of the 54 individuals heterozygous for Bw4, there were 5 cases whose set point viral loads were lower than 3.0 logs (2.0 to 3.0 logs). One possible reason might be associated with the role of the Bw4 motif. In addition to playing a role in presenting peptides and inducing immune responses, the Bw4 motif also acts as a specific ligand for NK cell inhibitory receptors (KIRs). This involves a defensive receptor, KIR3DS1, presenting stronger NK cell responses, thus suppressing HIV-1 replication and even protecting the host from opportunistic infections in the event of HIV-1 infection (28–30).

In addition to the B*57 allele, the B*44 allele was also observed to be associated with a lower set point viral load (P = 0.0017, q = 0.041) (Table 1). A previous study by Fabio et al. reported on the protection conferred by the B*44 allele against HIV. The B*44 and B*52 alleles were found to be associated with HIV resistance, and the B*51 allele was found to be associated with HIV susceptibility (31). Fabio's study implied the effect of the B*44 allele in protection from HIV infection. Tang et al. reported a significant association between B*44 and control of HIV-1 viremia during both the acute phase and the early chronic phase of the infection (14). In our study, individuals expressing the B*44 allele showed significantly lower set point viral loads than those who did not express the B*44 allele. Additionally, the B*44 allele was observed to play an important role in slowing CD4 decline as evidenced by the fact that there were far fewer B*44-positive individuals whose CD4 count declined to <350 than B*44-negative individuals (P = 0.026). It was also found that 7 of the 8 subjects homozygous for Bw4 had lower set point viral loads (2.0 to 4.0 logs) whereas 4 of the 5 subjects heterozygous for Bw4 had higher set point viral loads (4.0 to 5.0 logs). It could be that the Bw4 specificity of another allele on the HLA-B locus may enhance the effect of the B*44 allele on set point viral loads in an additive or synergistic manner. Further study, in a larger cohort, is needed in order to confirm this hypothesis.

Paris et al. reported that only B*44 was positively and significantly associated with a CTL response during two phase I and II HIV-1 vaccine trials involving a recombinant canarypox virus prime boosted with either recombinant monomeric gp120 or oligomeric gp160. This was indicated by the fact that 61.1% of B*44-positive volunteers had HIV-specific CTL responses at a frequency that was higher than in other HLA serotypes (32). However, Novitsky et al. reported that, at the level of the HLA supertype, a lower viral load was significantly associated with higher T cell responses to p24 for the A*02, A*24, B*27, and B*58 supertypes but not for the B*44 supertype in HIV-1 C subtype patients (33). In Novitsky's study, the B*44 supertype included not only B*4402 and B*4403 but also B*3701, B*60 (B*4001), B*61 (B*4006), B*18, B*4101, B*4901, and B*5001. In the present study, however, the lower viral load was found to be associated with higher HIV-specific T cell responses to a p24 pool in B*44-positive individuals, though only B*4402 and B*4403 were included. In addition, the peptide breadth of response within p24 in B*44-positive individuals was inversely associated with the level of viral load, although this was not statistically significant (Fig. 3). Moreover, not only was the magnitude of p24 pool-specific T cell responses lower in B*44-positive individuals (Fig. 2), but the magnitude of T cell responses to reacting peptides within p24 (Fig. 3) was also lower in B*44-positive individuals who expressed a Bw4 homozygote or heterozygote than in those B*44-negative individuals who expressed a Bw4 homozygote, though the level of viral load was insignificantly lower in the former than in the latter (P = 0.082, Mann-Whitney U test, data not shown). The six reacting peptides, including WMTNNPPIPVGDIYKRWI (p24; 101 to 118) and IVRMYSPVSILDIRQGPK (p24; 125 to 142), were recognized by the sample of at least 1 of the 5 B*44-positive individuals infected with HIV-1 CRF01_A/E. However, as Los Alamos National Security (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/immunology/) documented, the optimal CD8+ T cell responses to p24 peptides restricted by the B*44 allele in HIV-1 B-infected individuals were RDYVDRFYKTL (162 to 172) and AEQASQDVKNW (174 to 184). These findings imply that weak specific T cell responses to p24 might play a favorable role in the control of HIV viremia in HLA-B*44 allele HIV-1-infected individuals, but the intrinsic mechanisms involved in the association of the B*44 allele with the lower set point viral load need to be further confirmed using more patient cohorts.

In conclusion, the B*44 allele is associated with a lower set point viral load and might play a beneficial role in suppressing CD4 decline. In the current study, we found an inverse association between the p24-specific T cell responses and the level of viral load in B*44 allele-positive individuals, but the p24-specific T cell responses were weak. The factors underlying the control of HIV-1 viremia in acute HIV-1 infection may involve specific T cell responses restricted by the B*44 allele and/or NK cell responses mediated by Bw4 specificity. These possibilities need to be further explored to determine whether the B*44 HLA allele plays a favorable role in acute HIV-1 infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Major Project of Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Committee (D09050703590904 and D09050703590901) and the National 12th Five-Year Major Projects of China (2012ZX10001-003, 2012ZX10001-006, and 2012ZX10001-008) and Beijing Key Laboratory (BZ0089).

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Kaur G, Mehra N. 2009. Genetic determinants of HIV infection and progression to AIDS: susceptibility to HIV infection. Tissue Antigens 73:289–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaur G, Mehra N. 2009. Genetic determinants of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS: immune response genes. Tissue Antigens 74:373–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stephens Henry AF. 2005. HIV diversity versus HLA class I polymorphism. Trends Immunol. 26:41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Brien SJ, Gao X, Carrington M. 2001. HLA and AIDS: a cautionary tale. Trends Mol. Med. 7:379–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goulder PJ, Watkins DI. 2008. Impact of MHC class I diversity on immune control of immunodeficiency virus replication. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:619–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Streeck H, Nixon DF. 2010. T cell immunity in acute HIV-1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 202(Suppl 2):S302–S308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kiepiela P, Leslie AJ, Honeyborne I, Ramduth D, Thobakgale C, Chetty S, Rathnavalu P, Moore C, Pfafferott KJ, Hilton L, Zimbwa P, Moore S, Allen T, Brander C, Addo MM, Altfeld M, James I, Mallal S, Bunce M, Barber LD, Szinger J, Day C, Klenerman P, Mullins J, Korber B, Coovadia HM, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. 2004. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature 432:769–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Groot NG, Heijmans CM, Zoet YM, de Ru AH, Verreck FA, van Veelen PA, Drijfhout JW, Doxiadis GG, Remarque EJ, Doxiadis II, van Rood JJ, Koning F, Bontrop RE. 2010. AIDS-protective HLA-B*27/B*57 and chimpanzee MHC class I molecules target analogous conserved areas of HIV-1/SIVcpz. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:15175–15180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'Connell KA, Pelz RK, Dinoso JB, Dunlop E, Paik-Tesch J, Williams TM, Blankson JN. 2010. Prolonged control of an HIV type 1 escape variant following treatment interruption in an HLA-B*27-positive patient. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 26:1307–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Altfeld M, Addo MM, Rosenberg ES, Hecht FM, Lee PK, Vogel M, Yu XG, Draenert R, Johnston MN, Strick D, Allen TM, Feeney ME, Kahn JO, Sekaly RP, Levy JA, Rockstroh JK, Goulder PJ, Walker BD. 2003. Influence of HLA-B57 on clinical presentation and viral control during acute HIV-1 infection. AIDS 17:2581–2591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maiers M, Gragert L, Klitz W. 2007. High-resolution HLA alleles and haplotypes in the United States population. Hum. Immunol. 68:779–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Novitsky V, Flores-Villanueva PO, Chigwedere P, Gaolekwe S, Bussman H, Sebetso G, Marlink R, Yunis EJ, Essex M. 2001. Identification of most frequent HLA class I antigen specificities in Botswana: relevance for HIV vaccine design. Hum. Immunol. 62:146–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flores-Villanueva PO, Yunis EJ, Delgado JC, Vittinghoff E, Buchbinder S, Leung JY, Uglialoro AM, Clavijo OP, Rosenberg ES, Kalams SA, Braun JD, Boswell SL, Walker BD, Goldfeld AE. 2001. Control of HIV viremia and protection from AIDS are associated with HLA-Bw4 homozygosity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:5140–5145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tang J, Cormier E, Gilmour J, Price MA, Prentice HA, Song W, Kamali A, Karita E, Lakhi S, Sanders EJ, Anzala O, Amornkul PN, Allen S, Hunter E, Kaslow RA. 2011. Human leukocyte antigen variants B*44 and B*57 are consistently favorable during two distinct phases of primary HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africans with several viral subtypes. J. Virol. 85:8894–8902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Westreich DJ, Hudgens MG, Fiscus SA, Pilcher CD. 2008. Optimizing screening for acute human immunodeficiency virus infection with pooled nucleic acid amplification tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1785–1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fiebig EW, Wright DJ, Rawal BD, Garrett PE, Schumacher RT, Peddada L, Heldebrant C, Smith R, Conrad A, Kleinman SH, Busch MP. 2003. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS 17:1871–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hubert JB, Burgard M, Dussaix E, Tamalet C, Deveau C, Le Chenadec J, Chaix ML, Marchadier E, Vildé JL, Delfraissy JF, Meyer L, Rouzioux 2000. Natural history of serum HIV RNA levels in 330 patients with a known date of infection. The SEROCO Study Group. AIDS 14:123–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gay C, Dibben O, Anderson JA, Stacey A, Mayo AJ, Norris PJ, Kuruc JD, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Li H, Keele BF, Hicks C, Margolis D, Ferrari G, Haynes B, Swanstrom R, Shaw GM, Hahn BH, Eron JJ, Borrow P, Cohen MS. 2011. Cross-sectional detection of acute HIV infection: timing of transmission, inflammation and antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One 6:e19617. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fellay J, Shianna KV, Ge D, Colombo S, Ledergerber B, Weale M, Zhang K, Gumbs C, Castagna A, Cossarizza A, Cozzi-Lepri A, De Luca A, Easterbrook P, Francioli P, Mallal S, Martinez-Picado J, Miro JM, Obel N, Smith JP, Wyniger J, Descombes P, Antonarakis SE, Letvin NL, McMichael AJ, Haynes BF, Telenti A, Goldstein DB. 2007. A whole-genome association study of major determinants for host control of HIV. Science 317:944–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 57:289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cao K, Hollenbach J, Shi X, Shi W, Chopek M, Fernández-Viña MA. 2001. Analysis of the frequencies of HLA-A, B, and C alleles and haplotypes in the five major ethnic groups of the United States reveals high levels of diversity in these loci and contrasting distribution patterns in these populations. Hum. Immunol. 62:1009–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mellors JW, Margolick JB, Phair JP, Rinaldo CR, Detels R, Jacobson LP, Muñoz A. 2007. Prognostic value of HIV RNA, CD4 cell count, and CD4 cell count slope for progression to AIDS and death in untreated HIV infection. JAMA 297:2349–2350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mellors JW, Rinaldo CR, Jr, Gupta P, White RM, Todd JA, Kingsley LA. 1996. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science 272:1167–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaslow RA, Carrington M, Apple R, Park L, Muñoz A, Saah AJ, Goedert JJ, Winkler C, O'Brien SJ, Rinaldo C, Detels R, Blattner W, Phair J, Erlich H, Mann DL. 1996. Influence of combinations of human major histocompatibility complex genes in the course of HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 2:405–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Migueles SA, Sabbaghian MS, Shupert WL, Bettinotti MP, Marincola FM, Martino L, Hallahan CW, Selig SM, Schwartz D, Sullivan J, Connors M. 2000. HLA- B*5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:2709–2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Navis M, Schellens I, van Baarle D, Borghans J, van Swieten P, Miedema F, Kootstra N, Schuitemaker H. 2007. Viral replication capacity as a correlate of HLA B57/B5801-associated nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 179:3133–3143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gao X, Bashirova A, Iversen AK, Phair J, Goedert JJ, Buchbinder S, Hoots K, Vlahov D, Altfeld M, O'Brien SJ, Carrington M. 2005. AIDS restriction HLA allotypes target distinct intervals of HIV-1pathogenesis. Nat. Med. 11:1290–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qi Y, Martin MP, Gao X, Jacobson L, Goedert JJ, Buchbinder S, Kirk GD, O'Brien SJ, Trowsdale J, Carrington M. 2006. KIR/HLA pleiotropism: protection against both HIV and opportunistic infections. PLoS Pathog. 2:e79. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Martin MP, Gao X, Lee JH, Nelson GW, Detels R, Goedert JJ, Buchbinder S, Hoots K, Vlahov D, Trowsdale J, Wilson M, O'Brien SJ, Carrington M. 2002. Epistatic interaction between KIR3DS1 and HLA-B delays the progression to AIDS. Nat. Genet. 31:429–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alter G, Martin MP, Teigen N, Carr WH, Suscovich TJ, Schneidewind A, Streeck H, Waring M, Meier A, Brander C, Lifson JD, Allen TM, Carrington M, Altfeld M. 2007. Differential natural killer cell-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 replication based on distinct KIR/HLA subtypes. J. Exp. Med. 204:3027–3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fabio G, Scorza R, Lazzarin A, Marchini M, Zarantonello M, D'Arminio A, Marchisio P, Plebani A, Luzzati R, Costigliola P. 1992. HLA-associated susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 87:20–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paris R, Bejrachandra S, Karnasuta C, Chandanayingyong D, Kunachiwa W, Leetrakool N, Prakalapakorn S, Thongcharoen P, Nittayaphan S, Pitisuttithum P, Suriyanon V, Gurunathan S, McNeil JG, Brown AE, Birx DL, de Souza M. 2004. HLA class I serotypes and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses among human immunodeficiency virus-1-uninfected Thai volunteers immunized with ALVAC-HIV in combination with monomeric gp120 or oligomeric gp160 protein boosting. Tissue Antigens 64:251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Novitsky V, Gilbert P, Peter T, McLane MF, Gaolekwe S, Rybak N, Thior I, Ndung'u T, Marlink R, Lee TH, Essex M. 2003. Association between virus-specific T-cell responses and plasma viral load in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C infection. J. Virol. 77:882–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]