Abstract

Bacteria in the genus Rickettsiella (Coxiellaceae), which are mainly known as arthropod pathogens, are emerging as excellent models to study transitions between mutualism and pathogenicity. The current report characterizes a novel Rickettsiella found in the leafhopper Orosius albicinctus (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae), a major vector of phytoplasma diseases in Europe and Asia. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and pyrosequencing were used to survey the main symbionts of O. albicinctus, revealing the obligate symbionts Sulcia and Nasuia, and the facultative symbionts Arsenophonus and Wolbachia, in addition to Rickettsiella. The leafhopper Rickettsiella is allied with bacteria found in ticks. Screening O. albicinctus from the field showed that Rickettsiella is highly prevalent, with over 60% of individuals infected. A stable Rickettsiella infection was maintained in a leafhopper laboratory colony for at least 10 generations, and fluorescence microscopy localized bacteria to accessory glands of the female reproductive tract, suggesting that the bacterium is vertically transmitted. Future studies will be needed to examine how Rickettsiella affects host fitess and its ability to vector phytopathogens.

INTRODUCTION

Insects harbor a great diversity of facultative bacterial endosymbionts, many of which are transmitted primarily from females to their offspring (1), and it is now clear that these are major players in the ecology and evolution of their hosts (2). Because they are cryptic and often cannot be cultivated, these endosymbionts were until recently very poorly studied; molecular biology and genomics have enabled major advances in this field. Both biased and unbiased surveys of symbionts of arthropods have uncovered 5 major facultative bacterial endosymbiont lineages, Wolbachia, Rickettsia, Cardinium, Spiroplasma, and Arsenophonus, which are extremely widespread and successful across terrestrial arthropods (3). However, most insect endosymbionts have not been described, much less understood, and novel lineages are still being discovered (2).

One of the most important findings that has come from the molecular and genomic study of insect endosymbionts is that there are often very close links between mutualists and pathogens. This is reflected in two important ways. First, many lineages of bacteria, such as Spiroplasma, Serratia, and bacterial endosymbiont of the leafhopper Euscelidius variegatus (BEV), are often comprised of very closely related pathogens and mutualists (4–6). Second, symbionts and pathogens often use the same machinery to infect and affect their hosts, with perhaps the best-characterized example being the use of type III secretion systems to enter and alter host cells (7, 8). A major unresolved question is what mediates transitions between symbiosis and pathogenicity in these lineages.

A very promising lineage in which to study evolutionary transitions between symbiosis and pathogenicity is Rickettsiella. This genus comprises a poorly studied group of intracellular bacteria in the gammaproteobacteria, closely related to Legionella and Coxiella (9–11). Almost all known Rickettsiella are arthropod pathogens, including bacteria that cause diseases in beetles, moths, isopods, and crickets (as reviewed by Bouchon et al. [12]). Unbiased molecular surveys of bacterial associates of diverse arthropods have also uncovered Rickettsiella (13, 14), suggesting that these bacteria may be far more widespread and important than previously appreciated. The only nonpathogenic Rickettsiella characterized in detail is the one found in Acyrthosiphon pisum pea aphids. This bacterium infects ∼8% of A. pisum in western Europe and has been shown to change the body color of its hosts from red to green (15), a modification that has been hypothesized to reduce predation, although this has not yet been demonstrated. A recent study also showed that Rickettsiella protects pea aphids against pathogenic fungi by reducing aphid mortality and fungal sporulation (16).

This paper reports the discovery and characterization of a Rickettsiella infecting the leafhopper Orosius albicinctus (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) as part of an effort to identify its bacterial endosymbionts. This insect is a major agricultural pest, as it is a common and established vector of phytoplasma in Europe and the Middle East, including strains that cause the diseases sesamum phyllody, Lucerne witches' broom, purple top, and more (17). One of the long-term goals of this work is to identify symbionts that might interfere with the transmission of phytoplasma. To this end, this paper reports the results of unbiased surveys to characterize the symbionts of O. albicinctus as well as characterization of Rickettsiella through screening of insects in the field, phylogenetic analysis, and tissue localization using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Insect origin and maintenance.

Individuals of Orosius albicinctus, Anaceratagallia laevis, and Psammotettix (all belonging to the hemipteran family Cicadellidae) were collected from carrot (Daucus carota) fields in two locations in the Negev desert in Israel (Kibbutz Alumim [31°26′46.00″N, 34°30′37.97″E] and Shoket Junction [31°18′19.92″N, 34°53′17.37″E]) by vacuum sampling in October 2008 and April 2009. A laboratory colony of O. albicinctus was established from about 200 individuals vacuum collected from mint (Mentha spicata) plants at the B'sor Research and Development farm (31°16′15.17″N, 34°23′12.53″E) in January 2011. Leafhoppers were reared using a light/dark regimen of 13 h:11 h at 25 ± 2°C, with common bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris) as a food and reproductive source.

Initial unbiased surveys of Orosius albicinctus using DGGE.

In order to determine host bacterial community composition, DGGE was performed on 10 individuals collected from the above-mentioned carrot fields using previously described methods (18). Each individual insect was ground in lysis buffer (19) and incubated at 65°C for 15 min and then at 95°C for 10 min. DNA was kept at −4°C until further use. PCR was performed using general 16S rRNA bacterial primers (B341F and B907R; Table 1), and product separation was conducted on a 6% (wt/vol) acrylamide gel with a denaturing gradient ranging from 20% to 60% urea-formamide by electrophoresis at 90 V and 60°C for 16 h. After electrophoresis, the gels were incubated in ethidium bromide solution (250 ng/ml) for 10 min, rinsed in distilled water, and photographed under UV illumination. DNA was eluted from the DGGE bands and cloned into the pGEM T-Easy plasmid vector (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) and transformed into Escherichia coli. For each band, two colonies were randomly picked and sequenced (ABI 3700 DNA analyzer; Macrogen, Inc., South Korea), and the sequences obtained were compared to known sequences by using the BLAST algorithm (24) in the NCBI database. DGGE patterns consisted of both dominant and weak bands; the latter could not be sequenced properly. Therefore, mass sequencing (pyrosequencing) of 16S rRNA PCR products was performed in order to obtain an additional picture of the bacteria inhabiting the insect.

Table 1.

PCR primers and conditions used in the study

| Primer name | Target gene | Ta (°C)a | Product size (bp) | Primer sequence | Sequence for FISH | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RicO F | Rickettsiella (16S rRNA) | 66 | 404 | GGTGGGGAAGAAAGGTAACG | This study | |

| RicO R | GCCCCACACCTCACAGCTAG | 5′Cy5-CTAGCTGTGAGGTGTGGGGC | This study | |||

| SulO F | Sulcia (16S rRNA) | 50 | 418 | GAATAAAAAATTCTAATTATGG | This study | |

| SulO R | CACTTTCGCTTAACCACTG | 5′Cy3-CAGTGGTTAAGCGAAAGTG | 20 | |||

| B341F | General Bacteria (16S rRNA) | 60 | 550 | CGCCCGCCGCGCCCCGCGCCCGTCCCGCCGCCCCCGCCCGCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG | 21, 22 | |

| B907R | CCGTCAATTCMTTTGAGTTT | 21 | ||||

| 27F | General Bacteria (16S rRNA) | 57 | 1,480 | AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG | 23 | |

| 1513R | ACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT | 23 | ||||

| Ars F | Arsenophonus (23S) | 62 | 600 | CGTTTGATGAATTCATAGTCAAA | ||

| Ars R | GGTCCTCCAGTTAGTGTTACCCAAC | 50 |

Ta, annealing temperature.

454 pyrosequencing.

For pyrosequencing, DNA was extracted, as described by Chen et al. (25), from 20 individual O. albicinctus laboratory colonies; these had been maintained for at least 10 generations. Briefly, each individual insect was ground in SDS buffer and then incubated at 37°C for 1 h with RNase (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and then at 50°C for 1 h with proteinase K solution (Sigma). The homogenate was then extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. To precipitate DNA, 500 μl of chilled absolute ethanol (EtOH) was added, and the tube was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was washed twice with 500 μl of 70% ethanol and centrifuged, under the conditions described above, for 3 min to remove residual salt. The pellet was dried at 37°C for 30 min and resuspended in double-distilled water. The DNA extracted from all O. albicinctus individuals was pooled, and a 25-μl aliquot (DNA concentration, 20 ng/μl) was sent to the Research and Testing Laboratory (Lubbock, TX) for mass sequencing. Pyrosequencing was performed using the Roche 454 sequencing system as previously described (26) and the primers 27F and 519R, targeting the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. Retrieved sequences were analyzed using mothur software (http://www.mothur.org/). Sequences shorter than 200 bp, as well as those of low quality (multiple N, chimeras, etc.), were omitted. Sequences were aligned using the Silva compatible alignment database, and a distance matrix was calculated. Sequences were grouped into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% sequence similarity threshold (i.e., sequences that differ by ≤3% are clustered in the same OTU). Representatives of each OTU were classified with mothur, and their affiliation, down to the genus level, was verified by NCBI GenBank databases.

Prevalence of Rickettsiella and Arsenophonus in the field.

Both the DGGE and pyrosequencing analyses revealed the presence of several known bacterial symbionts, including Arsenophonus. In order to test for a possible association between that bacterium and Rickettsiella, their prevalences in 200 O. albicinctus individuals (100 males and 100 females) collected from mint screen houses at the Israeli Negev desert in January 2011 were determined. In addition, 10 A. laevis and 10 Psammotettix individuals that were collected at the same time as O. albicinctus from the carrot fields mentioned above were screened. Specimens were preserved in 96% ethanol for DNA extraction with lysis buffer (19) and subsequent screening, using PCR with symbiont-specific diagnostic primers (primer pair RicO F and RicO R and primer pair ArsF and ArsR; Table 1). PCRs were carried out in 25-μl volumes each containing 3 μl of the template DNA lysate, a 10 pM concentration of each primer, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 1× RedTaq buffer, and 1 U of RedTaq DNA polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich, Israel). The PCR program was carried out with an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 4 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at the primer-specific temperature (Table 1) for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 30 s. The cycle was completed with a final elongation step at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were visualized on a 1.2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. In order to verify the product identity, bands were eluted, cloned into the pGEM T-Easy plasmid vector, and transformed into E. coli. For each cloned product, two colonies were randomly picked and sequenced as described above. For samples that failed to amplify, an additional PCR was performed using primers that target the leafhopper nutritional symbiont Sulcia and symbiont-specific diagnostic primers (SulO F and SulO R; Table 1) as a positive control for DNA quality.

Phylogenetic analysis of leafhopper Rickettsiella.

Specific primers for Rickettsiella, designed based on the sequence obtained from DGGE analyses and combined with general bacterial primers (primer pair RicO F and 1513R and primer pair 27F and RicO R; Table 1), were used in order to sequence nearly the full 16S rRNA gene (∼1,500 bp) of the bacterium.

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using a data set of 16S rRNA gene sequences from diverse allied bacteria, including Rickettsiella, Diplorickettsia, and Coxiella, downloaded from the NCBI database. Sequences were organized using Geneious v5.5.4 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand) and aligned with the MUSCLE plug-in (27). The alignment was imported into MEGA v5.0 (28), and Modeltest (29) was used to determine the most appropriate nucleotide substitution model for phylogeny reconstruction using maximum likelihood. Node support was assessed using 1,000 bootstrap iterations. Branches with less than 50% bootstrap support were collapsed.

Vertical transmission of Rickettsiella.

In order to assess the potential for vertical transmission of Rickettsiella in O. albicinctus, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed on adult female reproductive tracts, which were dissected in a drop of saline buffer (9 g/liter NaCl) with the aid of a dissecting microscope. The procedure of FISH generally followed the method of Sakurai et al. (30), with slight modifications. The dissected ovaries were transferred into Carnoy's fixative for 1 h at room temperature, transferred to 96% EtOH, and then submerged in hybridization buffer. A 10-pmol volume of either Rickettsiella or Sulcia fluorescent probes (Table 1) was added to the hybridization buffer for 2 to 4 h before material was mounted on microscope slides in the probe-buffer solution. Stained samples were viewed under an IX81 Olympus FluoView 500 confocal microscope. Negative controls were performed by using a no-probe sample. Rickettsiella probe specificity was confirmed by the use of primer3 software in combination with the NCBI database. In addition, the sequence of this probe was aligned with sequences of each of the 21 most abundant bacterial species identified by the pyrosequencing analysis, obtained from the NCBI nr database. With the exception of Diplorickettsia, to which a complete match was found, less than a 50% sequence match to each of these bacteria was determined.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences obtained from DGGE analysis were deposited in GenBank (accession numbers KC764412 to KC764414). All sequences obtained from the 454 analysis were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (ERP002360).

RESULTS

DGGE and 454 pyrosequencing.

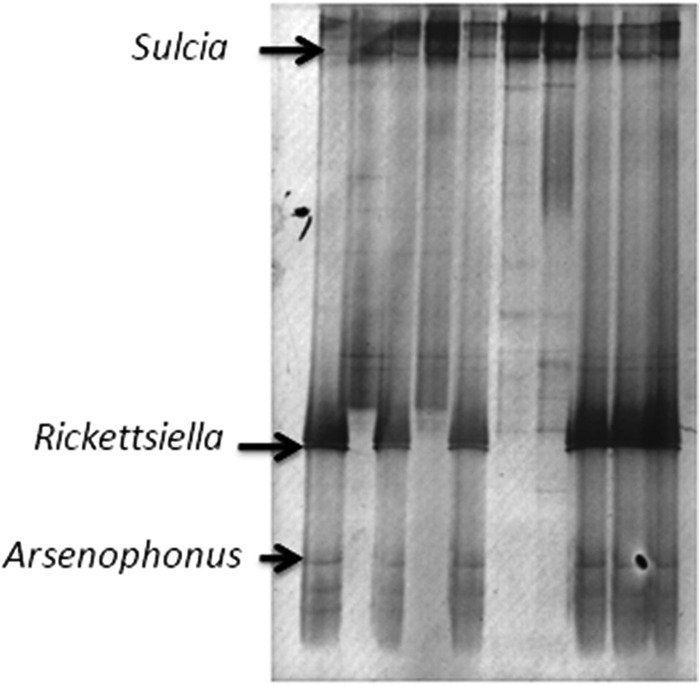

Three bacteria were identified by DGGE analysis of field-caught O. albicinctus (Fig. 1). There was one dominant band for all individuals, which corresponded to Sulcia and showed 98% similarity to a band corresponding to the 16S rRNA gene sequence of Sulcia muelleri originating from the leafhopper Matsumuratettix hiroglyphicus (GenBank accession no. JQ898318.1). Two additional bands corresponded to Arsenophonus (99% similar to the 16S rRNA sequence of the symbiont of the whitefly Trialeurodes hutchingsi; GenBank accession no. AY587140) and Rickettsiella (99% similar to the 16S rRNA sequence of the bacterium Diplorickettsia massiliensis and 94% similar to Rickettsiella sp. clone A03-05G; GenBank accession no. GQ857549 and FJ542836.1, respectively). Rickettsiella and Arsenophonus were present in 6 of 10 individuals screened by DGGE.

Fig 1.

DGGE analysis of 16S rRNA gene fragments, showing the bacterial community composition of Orosius albicinctus collected from carrot. The marked bands exhibited similarity to those of the 16S rRNA genes of Sulcia (98%), Arsenophonus (99%), and Rickettsiella (94%).

454 pyrosequencing yielded a total of 3,874 high-quality bacterial 16S rRNA sequences, ranging from 253 to 435 nucleotides in length, obtained from O. albicinctus that was maintained at the laboratory colony for 10 generations. These sequences were assigned to 149 OTUs at 97% sequence similarity. The most abundant bacterium in the data set was Rickettsiella (828 reads). Arsenophonus was the third-most-abundant bacterium (503 reads). Three other known bacterial symbionts were present in the data set, including the obligate nutritional symbionts of leafhoppers, Sulcia (17 sequences; the 21st-most-abundant bacterium), and Nasuia (18 sequences; the 20th-most-abundant bacterium). There were also 53 reads corresponding to Wolbachia (10th most abundant). Rounding out the remaining six most abundant bacteria were Kocuria (650 sequence; 2nd most abundant), Bergeyella (391 sequences; 4th most abundant), Hydrogenophaga (340 sequences; 5th most abundant), and Flavobacterium (179 sequences; 6th most abundant).

Prevalence of Rickettsiella and Arsenophonus in the field.

A total of 64 of 100 field-caught O. albicinctus females and 65 of 100 males carried Rickettsiella, while only 21 of 100 females and 18 of 100 males were infected with Arsenophonus. Of these, 54% of the insects were positive only for Rickettsiella, 9% only for Arsenophonus, and 9% for both bacteria, suggesting that there is no statistically significant association between these two facultative symbionts (P = 0.0874, two-tailed Fisher's exact test). Neither Rickettsiella nor Arsenophonus could be detected in the two other leafhopper species tested.

Phylogenetic analysis of leafhopper Rickettsiella.

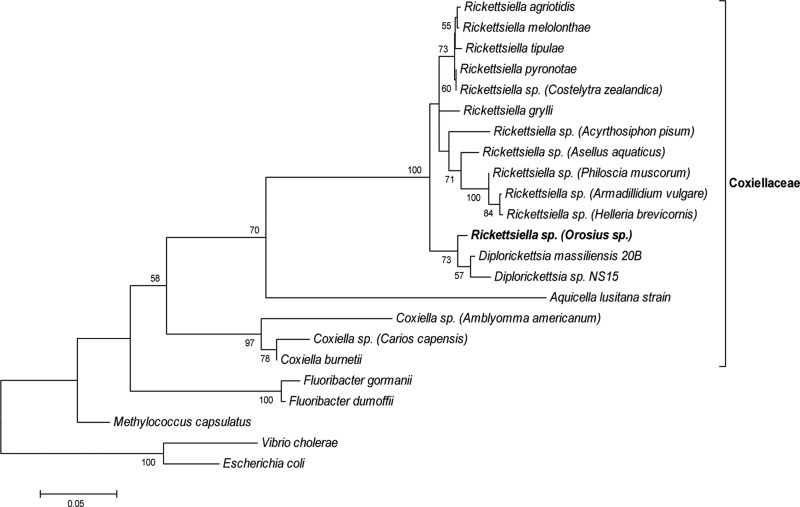

A nearly full-length portion (1,530 bp) of leafhopper Rickettsiella 16S rRNA was obtained. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis was performed, using a Kimura 2-parameter model with a gamma-distributed heterogeneity rate of nucleotide substitution (Fig. 2). The bacterium is nested within Rickettsiella and allied bacteria and appears to be closely affiliated with bacteria that were recently isolated from Ixodes ticks and placed in a new genus called Diplorickettsia (see Discussion below).

Fig 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree constructed using a Kimura 2-parameter + Γ model of nucleotide substitution and a nearly full-length 16S rRNA sequence. Designations of known hosts are presented in parentheses. Only bootstrap values of more than 50% are shown. The scale bar shows 0.05 substitutions per base.

Vertical transmission of Rickettsiella.

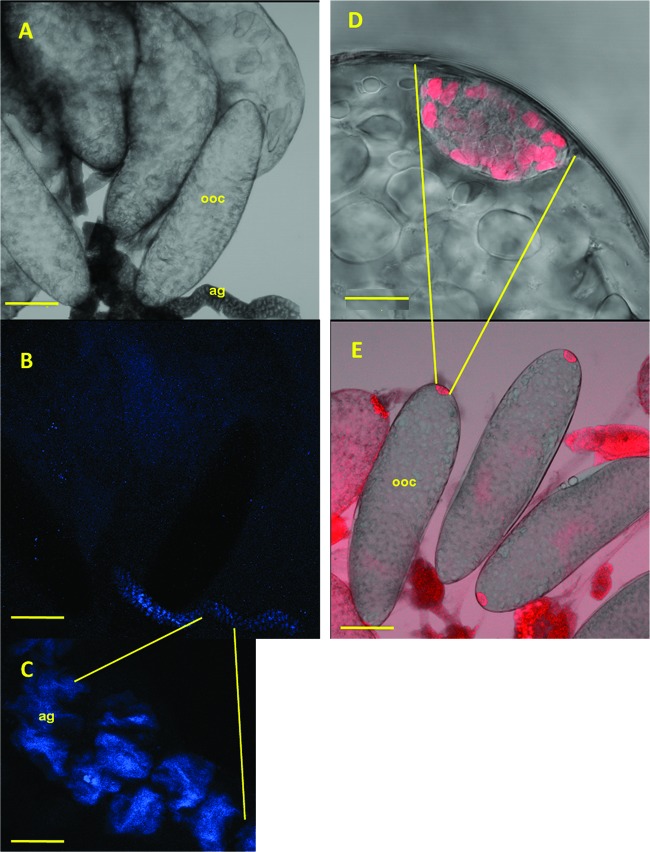

FISH of O. albicinctus ovaries showed that Sulcia is found in bacteriocytes located at the posterior end of the oocyte (Fig. 3D and E). In contrast, Rickettsiella was not detected in the oocyte. However, high densities of this secondary symbiont were seen in the accessory gland of the reproductive tract (Fig. 3A to C), where the bacteria seemed to be accumulated in vacuoles (Fig. 3C).

Fig 3.

Location of Rickettsiella (blue) and Sulcia (red) in Orosius. FISH images of the O. albicinctus reproductive tract, including the accessory gland (ag) at the end of the ovary, which is where oocyte (ooc) production and maturation into eggs take place, are shown. Rickettsiella was detected in the accessory gland of the reproductive tract (A to C), while Sulcia was detected in oocytes (D and E). Bars represent 200 μm (A, B, and E) or 20 μm (C and D) (the average adult body length is 3.5 mm).

DISCUSSION

The discovery of a Rickettsiella infecting O. albicinctus leafhoppers at high frequency is reported. The bacterium appears to be closely allied to a newly discovered intracellular bacterium infecting Ixodes ticks that was recently designated a new genus, Diplorickettsia (31). Designation as a new genus was motivated by two main findings. First, electron microscopy of Diplorickettsia maintained in a tick cell line revealed a distinct morphology, with bacteria being found primarily grouped in pairs. Second, the sequence determined for the tick bacterium was only 93% similar to the closest 16S rRNA sequences in the database (i.e., Rickettsiella). However, although many bacterial genera exhibit a divergence of greater than 95% for 16S rRNA, it is difficult to define genera based on definitive cutoff values, and there are many exceptions (as reviewed by Clarridge [32]); the designation of a new genus may be also premature, as Diplorickettsia may be nested within Rickettsiella (33). The leafhopper symbiont is therefore referred to here as Rickettsiella, and it will be interesting to determine whether it is also predominantly found in pairs. Sequencing multiple genes from many more Rickettsiella strains, including the one infecting O. albicinctus, will also help resolve the status of Diplorickettsia.

Although Rickettsiella, Arsenophonus, and Sulcia were identified by both DGGE and 454 pyrosequencing methods, Nasuia and Wolbachia were found only in the pyrosequencing survey, highlighting the importance of using multiple methods to describe symbiont communities. Among sap-feeding Hemiptera, virtually all Auchenorryncha harbor two lineages of obligate symbionts, termed coprimary symbionts, that complement each other and provide essential amino acids and vitamins that are missing from plant sap. One of these coprimary nutritional symbionts is almost always Sulcia (20), while the second member is more variable and is associated with more recently evolved lineages within Auchenorryncha. Examples of coprimary symbionts of Sulcia include Vidania in planthoppers (34), Hodgkinia in cicadas (35), Zinderia in spittlebugs (36), and Baumannia in sharpshooters and allies (37). The coprimary symbiont in deltocephaline leafhoppers, of which O. albicinctus is a member, was recently identified as a novel lineage in the betaproteobacteria and named Nasuia (38, 39). It is possible that Nasuia, Wolbachia, and other bacteria which were found in the pyrosequencing analysis were represented by weak bands in the DGGE gel and, therefore, that we were not able to sequence them. Both the DGGE and pyrosequencing screens also identified Arsenophonus as an abundant symbiont in O. albicinctus. Arsenophonus, a very common facultative inherited symbiont of terrestrial arthropods, was found to infect ∼4% of arthropod species in a recent large screening study of 136 species in 15 orders (3); Hemiptera, including leafhoppers, are commonly infected (3, 40).

Rickettsiella are primarily known as intracellular pathogens of arthropods, causing visible symptoms, and are lethal to their hosts (12); until now, only one nonpathogenic strain, a symbiont of pea aphids, has been characterized in detail (15, 16). The work presented here serves as a useful comparison of intracellular pathogens and nonpathogens, which, in addition to differing in their effects on host fitness, are expected to differ in prevalence in the field, tissue specificity, growth regulation, and mode of transmission. The prevalence of Rickettsiella in O. albicinctus was surprisingly high, with over 60% of individuals from a field sample infected. This is much higher than the prevalence of Rickettsiella in pea aphids, which has been reported to be ∼8% (15). Little is known about the prevalence of pathogenic Rickettsiella; insect pathogen abundance can be notoriously difficult to quantify in the field. For example, in a survey of potential pathogens of Agriotes wireworm beetle pests, of 3,420 individuals reared and screened for disease, only 1 was identified as harboring a new Rickettsiella pathotype (41). Molecular detection of Rickettsia, Coxiella, and Rickettsiella DNA in three native Australian tick species identified the presence of three Rickettsiella genotypes in only three Ixodes tasmani male samples (representing 8 individuals together). The other 34 I. tasmani individuals sampled, as well as two additional tick species (Bothriocroton concolor and Bothriocroton auruginans), were negative for Rickettsiella. The virulence factors, if any, of Rickettsiella genotypes detected on the tick host remained unknown in this study (42).

Nonpathogenic intracellular bacteria are also expected to grow much more slowly in their hosts and to be restricted to specific tissues. Indeed, the FISH analysis showed that within the ovaries, Rickettsiella can be seen only in the accessory glands. More-detailed FISH studies will be required to determine if the leafhopper Rickettsiella is more restricted in its localization than the pea aphid Rickettsiella, which was observed in sheath cells, oenocytes, and specialized cells, termed secondary bacteriocytes, in ovaries and embryos (15). Additionally, the presence of that symbiont in other tissues may shed more light on possible differences between the bacteria found in various hosts, because the aphid Rickettsiella, for example, was found to be located both intra- and extracellularly and is abundant in hemolymph.

The presence of Rickettsiella in pea aphid ovaries and embryos highlights a key evolutionary transition observed in many beneficial insect endosymbionts—the ability to be transmitted from mothers to their offspring with high efficiency. This contrasts with pathogenic Rickettsiella, which is transmitted horizontally, infecting new hosts in the soil (12).

In the current study, Rickettsiella bacteria were not observed in O. albicinctus oocytes, so it is not clear whether (and if so, how) they are maternally inherited. Future experiments will be required to confirm and quantify vertical transmission. Interestingly, Rickettsiella was abundant in ovarian accessory glands. Although similar accessory glands have been described in other cicadellids (43–45), little is known about them. In other insects, ovarian accessory glands often provide protective coatings or adhesive secretions for eggs (46, 47). This raises the possibility that Rickettsiella is secreted over the eggs. This has been demonstrated in Arsenophonus nasoniae, an extracellular and cultivable male-killing symbiont of Nasonia parasitic wasps (48). In addition, a number of heteropteran bugs, such as plataspid stink bugs, harbor in their midguts nutritional bacterial symbionts that are smeared over eggs during oviposition and ingested by hatching larvae (49). We are not aware of other studies showing bacteria housed in hemipteran ovarian glands.

Much more detailed experimental work will be required to understand how Rickettsiella affects the fitness of its leafhopper hosts and how it persists in its host populations. Rickettsiella did not cause visible symptoms in the leafhopper in this study, and stable infections were maintained for at least a year and a half (10 generations); this suggests that this bacterium is nonpathogenic. Further examination is also required to determine the effect of these bacteria on the ability of O. albicinctus to function as a vector of phytopathogens and on interactions between Rickettsiella and other microorganisms infecting O. albicinctus. To this end, the recent finding that Rickettsiella protects pea aphids against virulent fungal pathogens (16) suggests a promising path forward.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by research grant no. CA-9110-09 from BARD, the United States-Israel Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund, to E.Z.-F. and by an NSERC (National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada) Special Research Opportunity Canada-Israel Grant (SROCI-386044-2009) to S.J.P. S.J.P. acknowledges support from the Integrated Microbial Biodiversity Program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. L.I.-K. acknowledges support from the Lady Davis Fellowship Trust, Technion.

Thanks are extended to Eduard Belausov for technical support and to Oded Beja for scientific support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Moran NA, McCutcheon JP, Nakabachi A. 2008. Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42:165–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zchori-Fein E, Bourtzis K. 2011. Manipulative tenants: bacteria associated with arthropods. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 3. Duron O, Bouchon D, Boutin S, Bellamy L, Zhou L, Engelstädter J, Hurst GD. 2008. The diversity of reproductive parasites among arthropods: Wolbachia do not walk alone. BMC Biol. 6:27. 10.1186/1741-7007-6-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Degnan PH, Bittleston LS, Hansen AK, Sabree ZL, Moran NA, Almeida RPP. 2011. Origin and examination of a leafhopper facultative endosymbiont. Curr. Microbiol. 62:1565–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burke GR, Normark BB, Favret C, Moran NA. 2009. Evolution and diversity of facultative symbionts from the aphid subfamily Lachninae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:5328–5335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Regassa LB, Gasparich GE. 2006. Spiroplasmas: evolutionary relationships and biodiversity. Front. Biosci. 11:2983–3002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dale C, Plague GR, Wang B, Ochman H, Moran NA. 2002. Type III secretion systems and the evolution of mutualistic endosymbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:12397–12402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pontes MH, Smith KL, De Vooght L, Van Den Abbeele J, Dale C. 2011. Attenuation of the sensing capabilities of PhoQ in transition to obligate insect-bacterial association. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002349. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fournier PE, Raoult D. 2005. Genus II Rickettsiella, p 241–248 In Brenner DJ, Krieger-Huber S, Stanley JT. (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roux V, Bergoin M, Lamaze N, Raoult D. 1997. Reassessment of the taxonomic position of Rickettsiella grylli. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:1255–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cordaux R, Paces-Fessy M, Raimond M, Michel-Salzat A, Zimmer M, Bouchon D. 2007. Molecular characterization and evolution of arthropod-pathogenic Rickettsiella bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5045–5047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bouchon D, Cordaux R, Grève P. 2011. Rickettsiella, intracellular pathogens of arthropods, p 127–148 In Zchori-Fein E, Bourtzis K. (ed), Manipulative tenants: bacteria associated with arthropods. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reeson AF, Jankovic T, Kasper ML, Rogers S, Austin AD. 2003. Application of 16S rDNA-DGGE to examine the microbial ecology associated with a social wasp Vespula germanica. Insect Mol. Biol. 12:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spaulding AW, Von Dohlen CD. 2001. Psyllid endosymbionts exhibit patterns of co-speciation with hosts and destabilizing substitutions in ribosomal RNA. Insect Mol. Biol. 10:57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsuchida T, Koga R, Horikawa M, Tsunoda T, Maoka T, Matsumoto S, Simon J-C, Fukatsu T. 2010. Symbiotic bacterium modifies aphid body color. Science 330:1102–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Łukasik P, van Asch M, Guo H, Ferrari J, Godfray HCJ. 2013. Unrelated facultative endosymbionts protect aphids against a fungal pathogen. Ecol. Lett. 16:214–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weintraub PG, Jones P. 2010. Phytoplasmas: genomes, plant hosts and vectors. CABI Publishing, Cambridge, MA [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gottlieb Y, Ghanim M, Chiel E, Gerling D, Portnoy V, Steinberg S, Tzuri G, Horowitz AR, Belausov E, Mozes-Daube N, Kontsedalov S, Gershon M, Gal S, Katzir N, Zchori-Fein E. 2006. Identification and localization of a Rickettsia sp. in Bemisia tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3646–3652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frohlich DR, Torres-Jerez I, Bedford ID, Markham PG, Brown JK. 1999. A phylogeographical analysis of the Bemisia tabaci species complex based on mitochondrial DNA markers. Mol. Ecol. 8:1683–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moran NA, Tran P, Gerardo NM. 2005. Symbiosis and insect diversification: an ancient symbiont of sap-feeding insects from the bacterial phylum Bacteroidetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8802–8810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Muyzer G, Brinkhoff T, Nübel U, Santegoeds C, Schäfer H, Wawer C. 1997. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) in microbial ecology, p 1–27 In Akkermans ADL, Van Elsas JD, De Bruijn FJ. (ed), Molecular microbial ecology manual. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reference deleted.

- 23. Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 1991. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173:697–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen H, Rangasamy M, Tan SY, Wang H, Siegfried BD. 2010. Evaluation of five methods for total DNA extraction from Western corn rootworm beetles. PLoS One 5:e11963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dowd SE, Callaway TR, Wolcott RD, Sun Y, McKeehan T, Hagevoort RG, Edrington TS. 2008. Evaluation of the bacterial diversity in the feces of cattle using 16S rDNA bacterial tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing (bTEFAP). BMC Microbiol. 8:125. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Posada D, Crandall KA. 1998. Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14:817–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sakurai M, Koga R, Tsuchida T, Meng XY, Fukatsu T. 2005. Rickettsia symbiont in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum: novel cellular tropism, effect on host fitness, and interaction with the essential symbiont Buchnera. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4069–4075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mediannikov O, Sekeyová Z, Birg ML, Raoult D. 2010. A novel obligate intracellular gamma-proteobacterium associated with ixodid ticks, Diplorickettsia massiliensis, gen. nov., sp. nov. PLoS One 5:e11478. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clarridge JE. 2004. Impact of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis for identification of bacteria on clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:840–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leclerque A, Kleespies RG. 2012. A Rickettsiella bacterium from the hard tick, Ixodes woodi: molecular taxonomy combining multilocus sequence typing (MLST) with significance testing. PLoS One 7:e38062. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Urban JM, Cryan JR. 2012. Two ancient bacterial endosymbionts have coevolved with the planthoppers (Insecta: Hemiptera: Fulgoroidea). BMC Evol. Biol. 12:87. 10.1186/1471-2148-12-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCutcheon JP, McDonald BR, Moran NA. 2009. Convergent evolution of metabolic roles in bacterial co-symbionts of insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:15394–15399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McCutcheon JP, Moran NA. 2010. Functional convergence in reduced genomes of bacterial symbionts spanning 200 My of evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 2:708–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu D, Daugherty SC, Van Aken SE, Pai GH, Watkins KL, Khouri H, Tallon LJ, Zaborsky JM, Dunbar HE, Tran PL, Moran NA, Eisen JA. 2006. Metabolic complementarity and genomics of the dual bacterial symbiosis of sharpshooters. PLoS Biol. 4:e188. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Noda H, Watanabe K, Kawai S, Yukuhiro F, Miyoshi T, Tomizawa M, Koizumi Y, Nikoh N, Fukatsu T. 2012. Bacteriome-associated endosymbionts of the green rice leafhopper Nephotettix cincticeps (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 47:217–225 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bennett GM, O'Grady PM. 2012. Host-plants shape insect diversity: phylogeny, origin, and species diversity of native Hawaiian leafhoppers (Cicadellidae: Nesophrosyne). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 65:705–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Russell JA, Funaro CF, Giraldo YM, Goldman-Huertas B, Suh D, Kronauer DJC, Moreau CS, Pierce NE. 2012. A veritable menagerie of heritable bacteria from ants, butterflies, and beyond: broad molecular surveys and a systematic review. PLoS One 7:e51027. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kleespies RG, Ritter C, Zimmermann G, Burghause F, Feiertag S, Leclerque A. 2013. A survey of microbial antagonists of Agriotes wireworms from Germany and Italy. J. Pest Sci. 86:99–106 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vilcins IME, Old JM, Deane E. 2009. Molecular detection of Rickettsia, Coxiella and Rickettsiella DNA in three native Australian tick species. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 49:229–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tsai JH, Perrier JL. 1996. Morphology of the digestive and reproductive systems of Dalbulus maidis and Graminella nigrifons (Homoptera: Cicadellidae). Fla. Entomol. 79:563–578 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gil-Fernandez C, Black LM. 1965. Some aspects of the internal anatomy of the leafhopper Agallia constricta (Homoptera: Cicadellidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 58:275–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hummel NA, Zalom FG, Peng CYS. 2006. Anatomy and histology of reproductive organs of female Homalodisca coagulata (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Proconiini), with special emphasis on categorization of vitellogenic oocytes. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2:920–932 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Elzinga RJ. 2003. Fundamentals of entomology, 6th ed Pearson/Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 47. Triplehorn CA, Johnson NF. 2005. Borror and DeLong's introduction to the study of insects, 7th ed Thomson Brooks/Cole, Belmont, CA [Google Scholar]

- 48. Werren JH, Skinner SW, Huger AM. 1986. Male-killing bacteria in a parasitic wasp. Science 231:990–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fukatsu T, Hosokawa T. 2002. Capsule-transmitted gut symbiotic bacterium of the Japanese common plataspid stinkbug, Megacopta punctatissima. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:389–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thao ML, Baumann P. 2004. Evidence for multiple acquisition of Arsenophonus by whitefly species (Sternorrhyncha: Aleyrodidae). Curr. Microbiol. 48:140–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]