Abstract

Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) can be functionalized and/or recycled via hydrolysis by microbial cutinases. The rate of hydrolysis is however low. Here, we tested whether hydrophobins (HFBs), small secreted fungal proteins containing eight positionally conserved cysteine residues, are able to enhance the rate of enzymatic hydrolysis of PET. Species of the fungal genus Trichoderma have the most proliferated arsenal of class II hydrophobin-encoding genes among fungi. To this end, we studied two novel class II HFBs (HFB4 and HFB7) of Trichoderma. HFB4 and HFB7, produced in Escherichia coli as fusions to the C terminus of glutathione S-transferase, exhibited subtle structural differences reflected in hydrophobicity plots that correlated with unequal hydrophobicity and hydrophily, respectively, of particular amino acid residues. Both proteins exhibited a dosage-dependent stimulation effect on PET hydrolysis by cutinase from Humicola insolens, with HFB4 displaying an adsorption isotherm-like behavior, whereas HFB7 was active only at very low concentrations and was inhibitory at higher concentrations. We conclude that class II HFBs can stimulate the activity of cutinases on PET, but individual HFBs can display different properties. The present findings suggest that hydrophobins can be used in the enzymatic hydrolysis of aromatic-aliphatic polyesters such as PET.

INTRODUCTION

Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) is a thermoplastic polyester with excellent tensile and impact strength, transparency, and appropriate thermal stability (1). Because of its high production (36 million tons per year [2]), PET constitutes a significant waste material, which, although not representing a direct hazard to the environment, is not readily decomposed in nature.

Enzymatic recycling of polymers and particularly of PET basically would break down the polymer into its building blocks ethylene glycol (EG) and terephthalic acid (TA). These have a high value and can be reused in chemical synthesis, including the production of PET. This would avoid current limitations in PET recycling, which, e.g., requires pure PET fractions or has to fight with enrichment of contaminants (3). In addition, the surface modification of PET to increase its hydrophilicity is an essential step in processing for many applications ranging from textiles to medical and electronics. Synthetic polymers and particularly PET show excellent chemical resistance, but this feature makes them very difficult to be functionalized and is a great drawback for the processing steps. Current methods, including the use of harsh chemicals, concentrated acid or alkali, or different types of plasma approaches pursue to insert reactive moieties. Therefore, enzymatic strategies have recently received considerable attention (for a review, see reference 2) due to their environmentally friendly profile compared to currently used techniques such as those based on concentrated alkali (4) or the limitation of plasma methods (5) to planar surfaces.

Compared to traditional approaches, enzymatic partial hydrolysis of the surface achieves the same degree of functionalization minus the loss of material, up to 15% in the case of concentrated alkali (4), or tensile strength. Compared to plasma approaches, a lower consumption of energy and a higher stability of the groups created on the surface can be achieved by enzymatic methods (6).

PET hydrolysis can be achieved by enzymes from distinct classes, such as esterases (7), lipases (8), and cutinases (9, 10), the latter thereby yielding the most promising results (11). Cutinases hydrolyze cutin, an insoluble, cross-linked, lipid-polyester matrix comprised of n-C17 and n-C18 hydroxy and epoxy fatty acids that is the main component of plant cuticule, a barrier against dehydration and invasion of aerial plant tissues (12). Cutinases are best known from plant pathogenic fungi, where they facilitate the fungus' penetration through the cuticle (13). Because of the ability of cutinases to hydrolyze cutin, they have been exploited for reactions with small-molecule esters and synthetic polyesters (14, 15). Although these results are promising, the hydrolysis rate is generally low, probably due to limitations in sorption to hydrophobic polyester. Fungi produce small cysteine-rich proteins, hydrophobins, that can naturally adsorb to hydrophobic surfaces and to interfaces between hydrophobic (air, oil, and wax) and hydrophilic (water and cell wall) phases (16–18). Interestingly, growth of the mold fungus Aspergillus oryzae on the biodegradable polyester polybutylene succinate-coadipate (PBSA) induced not only the respective cutinase (CutL1) but also a hydrophobin (RolA), which adsorbed to the hydrophobic surface of PBSA, recruited CutL1, and stimulated its hydrolysis of PBSA (17).

A comparative evolutionary analysis has revealed that species of the fungal genus Trichoderma (Hypocreales, Ascomycota, and Dikarya) possess the highest number and diversity of class II hydrophobins among fungi (Ascomycota) (19) of which only three have thus far been characterized (Trichoderma reesei HFB1 and HFB2 and Trichoderma atroviride SRH1 [20, 21]). Many Trichoderma species display an opportunistic lifestyle with profound saprotrophic abilities on diverse natural substrata and, moreover, have developed an ability for various biotrophic interactions with fungi, plants, and animals (22), all of which require attachment to various hydrophobic surfaces (cf. reference 23). It is tempting to speculate that the expanded arsenal of hydrophobins may be involved in this property. In fact, hydrolysis of the natural polyesters cutin and suberin by a Coprinopsis cinerea polyesterase was enhanced in the presence of T. reesei HFB2 (24).

The hypothesis of the present study was that Trichoderma hydrophobins can stimulate the enzymatic modification of synthetic polymers such as PET. To this end, we have identified two thus-far-unknown, evolutionarily derived clades of hydrophobins from three Trichoderma spp.: HFB4 and HFB7. We show that although these hydrophobins indeed stimulate the hydrolysis of PET by cutinase from Humicola insolens, the effects of HFB4 and HFB7 are different.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and enzymes.

Methanol and acetonitrile were purchased from Roth (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). All other chemicals were of analytical grade from Sigma (Germany). The H. insolens cutinase was kindly provided by Novozymes (Bejing, China). Amorphous PET films were purchased from Goodfellow (Huntingdon, United Kingdom).

Microbial strains and cultivations.

Stellar competent cells from E. coli HST04 were purchased from Clontech (TaKaRa Bio Company, CA) and were used for the cloning of hydrophobin-encoding genes and the propagation of plasmid DNA. E. coli BL21 (protease deficient) and expression plasmid pGEX-4T-2 were purchased from GE Healthcare (Amersham, England).

The Trichoderma strains used in the present study were T. reesei QM6a, T. atroviride IMI 206040, and T. virens Gv29-8. Stock cultures were kept at −80°C in the Collection of Industrial Microorganisms of Vienna University of Technology (Austria). All cultures were maintained on plates containing malt extract (MEX) agar (30 g of malt extract liter−1 and 20 g of agar liter−1 in tap water) at 25 to 28°C.

Phylogenetic analysis.

For the phylogenetic analysis, sequences were aligned with CLUSTAL X 1.81 (25) and then visually checked in GeneDoc 2.6 (26). The interleaved NEXUS file was formatted by using PAUP*4.0b10 (27). Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling was performed using MrBayes v.3.0B4 with two simultaneous runs of four incrementally heated chains that performed for 5 million generations. The sufficient number of generations for each data set was determined by using the AWTY graphical system (28) to check for the convergence of the MCMC. Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) were obtained from the 50% majority-rule consensus of trees sampled every 100 generations after removing the first trees. PP values lower than 0.95 were not considered significant, while PP values below 0.9 are not shown on the resulting phylograms.

DNA isolation, hfb4 and hfb7 amplification, and sequencing.

Mycelia were harvested after 2 days of growth from the surface of the cellophane membranes on MEX agar plates and genomic DNA was isolated by using a Qiagen DNeasy plant minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. PCR amplification was carried out in an iCycler iQ (Bio-Rad) for 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min of denaturing, 65°C for 1 min of annealing, and 72°C for 50 s of extension. Initial denaturing was at 94°C for 1 min, and the final extension was performed at 72°C for 7 min. Primers used for amplification are given in Table 1. PCR fragments were purified (PCR purification kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced at MWG (Ebersberg, Germany).

Table 1.

PCR primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′)a |

Tm (°C) | Application | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |||

| hfb4_a | GCCTCTCTGGCCATTGCCGCGCCYGC | AGAGCATCCTGGCACAAAACACCRAG | 65 | hfb4 amplification |

| hfbHV | CAACCACTTCCACATTCAAA | GAACCCCGTGATGCCTTG | 59 | hfb7 amplification |

| hfb4ree | GGTTCCGCGTGGATCCGCCGCTGCCGACATTGCTA | GATGCGGCCGCTCGAGGGGAATTTACTCGGGGAGAGCA | 65 | Cloning into pGEX-4T-2 |

| hfb4atro | GGTTCCGCGTGGATCCGCGCCTGCTTCTGAGGTCGT | GATGCGGCCGCTCGAGTTACAGGGGAAGAGCATCCTGGCA | 65 | Cloning into pGEX-4T-2 |

| hfb4virens | GGTTCCGCGTGGATCCCCCGCTGGGGAGACGACTACT | GATGCGGCCGCTCGAGTTACTCGGGAAGAGCATCCTGGCA | 65 | Cloning into pGEX-4T-2 |

| Hfb7virens | GGTTCCGCGTGGATCCCAACCACTTCCACATTCAAA | GATGCGGCCGCTCGAGTTCACCATCCAAAGTACAGCTA | 59 | Cloning into pGEX-4T-2 |

Restriction sites are underlined.

HFB4 and HFB7 production and analysis.

The hfb4 and hfb7 genes were expressed as fusion proteins to C terminus to glutathione S-transferase (GST) in E. coli BL21 under the lacZ promoter as described by Pail et al. (29). GST alone was expressed with the same vector, but without a fusion partner. The primers listed in Table 1 were used to amplify corresponding cDNA fragments and ligation into vector pGEX4T-2, as described by the manufacturer (GE Healthcare). After cultivation and induction by IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% Triton X-100 and then disrupted by sonication. The crude extract obtained after centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 4°C, 10 min) was subjected to affinity chromatography on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare). Protein concentration was determined using a dye-binding assay (30). SDS-PAGE was performed according to standard protocols, using 15% polyacrylamide gels, followed by staining with Coomassie blue (31).

Surface activity of HFB4 and HFB7.

PET films and glass pieces (1.5 by 0.7 cm) were defatted with 70% (wt/vol) ethanol. Thereafter, samples were first washed with 5 g of Triton X-100/liter, then with 100 mM Na2CO3, and finally with deionized water (each step was 30 min at 50°C); the samples were then incubated with a Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 7) containing a final concentration of 50 μg of the corresponding GST-HFB or GST proteins/ml. After 12 h of incubation at 50°C, the PET and glass pieces were washed twice with water and dried for 10 min at 50°C. Water contact angles (WCAs) were determined in a drop-shape analysis system (DSA 100; Kruss GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) using deionized water as the test liquid with a drop volume of 2 μl. Water droplets were set onto the surface of the PET or glass pieces, and the contact angles were determined after 3 s.

PET hydrolysis.

Prior to the enzyme treatment, PET films were cut into pieces (1 by 2 cm) and washed first with 5 g of Triton X-100/liter, then with 100 mM Na2CO3, and finally with deionized water (each step was 30 min at 50°C). The PET pieces were then placed in a 2-ml Eppendorf tube, followed by incubation with cutinase (final concentration, 0.2 mg/ml) and GST-HFB protein in final concentrations of 0.05 to 50 μg/ml) in a total volume of 2 ml of 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0). Pure GST was used as a control. The tubes were then placed on a Thermomixer (Eppendorf) at 130 rpm, and hydrolysis was performed at 50°C for 24 h. Thereafter, the proteins were precipitated by adding an equal volume of absolute methanol, followed by centrifugation (MIKRO 200R; Hettich, Tuttlingen, Germany) at 16,000 × g (0°C, 15 min). The supernatant was acidified by the addition of 1 μl of concentrated HCl and subjected to high-pressure liquid chromatography analysis on a reversed-phase column, RP-C18 (Discovery HS-C18, 5 μm, 150 by 4.6 mm with precolumn; Supelco, Bellefonte, PA) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min (25°C) with a mixture (1:1:3 [vol/vol/vol]) of acetonitrile, 10 mM sulfuric acid, and water as the eluent. Detection of the analytes—terephthalic acid (TA), mono-(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (MHET), and bis-(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (BHET)—was performed with a photodiode array detector at the wavelength of 241 nm.

HFB concentrations that yield half-maximal stimulation (A0.5) were calculated from double-reciprocal plots of the resulting cutinase activity (i.e., the activity increase observed in the presence of HFB versus that observed in its absence) versus the GST-HFB protein concentration.

RESULTS

Selection of Trichoderma hydrophobins.

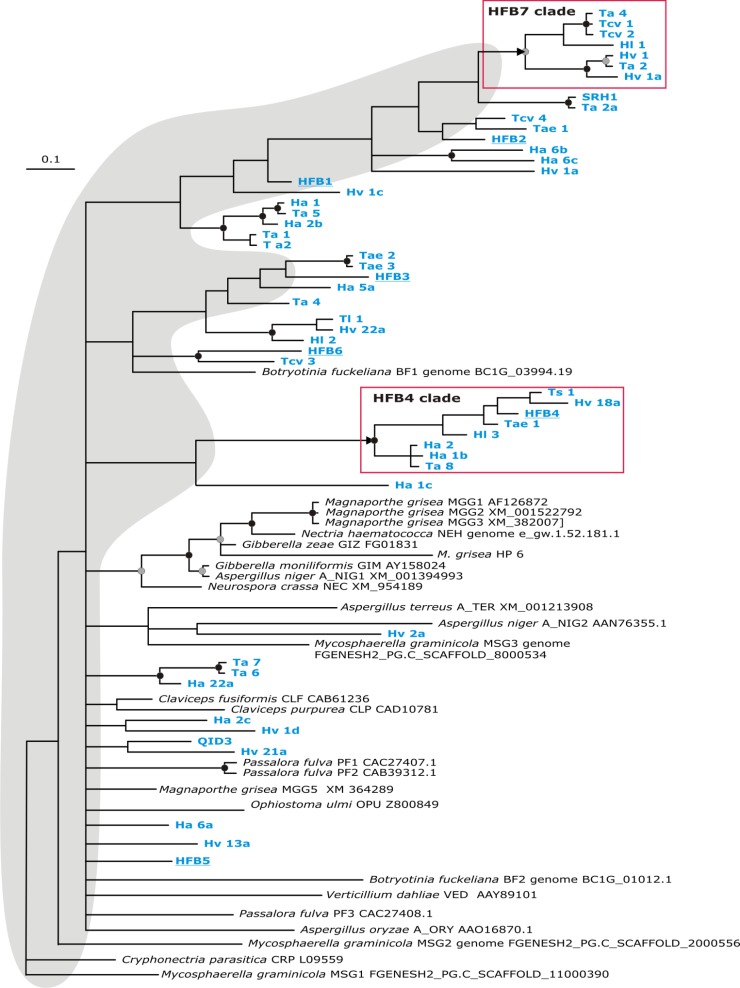

Our previous work has shown an outstanding diversity of Trichoderma hydrophobins that evolve under purifying selection pressure (19). For the present study, we assumed that the most evolutionarily derived Trichoderma HFBs would serve as the best candidates to study a possible variability in binding to hydrophobic surfaces and eventual stimulation of PET hydrolysis. To identify such hydrophobins, we subjected hydrophobin amino acid sequences that were previously used to study hydrophobin evolution (19) to a Bayesian analysis. The result of this approach is shown in Fig. 1: as noted also in other studies (19, 32), the internal structure in the hydrophobin tree is essentially unresolved, which is likely due to purifying selection operating on these proteins. However, several clades in the phylogram are supported by high posterior probabilities (PP > 0.94, labeled by black circles in Fig. 1). Interestingly, the phylogenetic positions of the previously characterized hydrophobins HFB1 and HFB2 from T. reesei (21) and SRH1 from T. atroviride (20) are not resolved in this phylogram. However, the resulting two most terminal subclades obtained high statistical support (marked by frames on Fig. 1). One of them contained previously identified HFB4 from T. reesei, while another was formed by thus-far-uncharacterized hydrophobins from T. aggressivum, T. harzianum, and T. virens. Since hydrophobin families have thus far been numbered from 1 to 6 according to the six characterized hydrophobins from T. reesei (33), we term the members of this clade tentatively HFB7 for the purpose of our study. Because HFB4 and HFB7 were members of two most recent evolutionary clades, we selected them for study. Investigation of the occurrence of these proteins in the three Trichoderma spp. for which a genome sequence has been published (34, 35) revealed that HFB4 was present in all three species (T. reesei QM 6a, accession no. EGR49614; T. virens Gv29-8, accession no. ABS59378; and T. atroviride IMI 206040, accession no. ABS59362), whereas HFB7 was present only in T. virens Gv29-8 (accession no. ABS59373). However, the latter is also present in several other species of Trichoderma and thus is not unique to T. virens (I. S. Druzhinina, unpublished data).

Fig 1.

Bayesian phylogram based on the amino acid alignment of HFBs from Trichoderma (indicated in boldface blue type) and other Ascomycota. T. reesei HFB1 to HFB6 are underlined. Sequence accession numbers for hydrophobins are given in the figure or in reference 19. Black circles above nodes indicate posterior probabilities of >0.94. The HFB4 and HFB7 clades are boxed. The gray-shaded area indicates the unresolved internal structure of the tree.

Structural properties of HFB4 and HFB7.

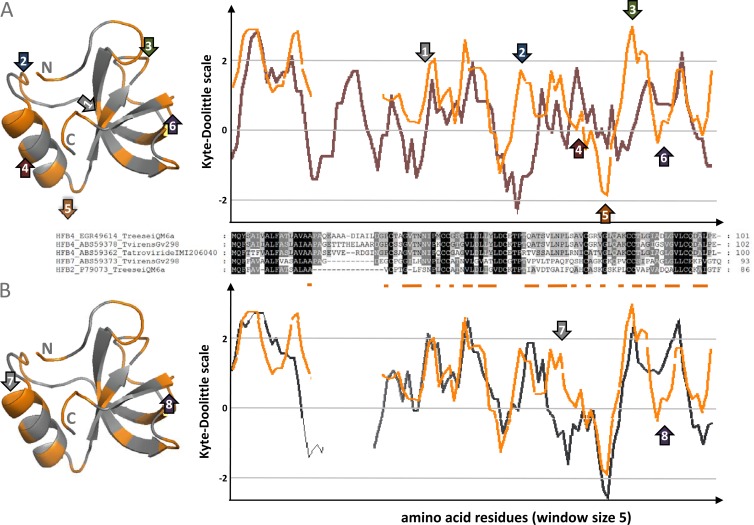

The amino acid sequences of HFB4 and HFB7 (100 to 102 amino acids [aa] and 93 aa in total lengths, respectively) between C1 and C8 consisted of 52 aa that were alignable without indels but were nevertheless considerably polymorphic: it comprised only 15 identical amino acid residues (including the 8 cysteines) and 10 functionally conserved amino acids, leaving 27 aa variable (Fig. 2). A similar genetic distance was evident between HFB4 and HFB2 (21), which is related to the HFB7 clade, and between HFB4 and HFB1 (21), which is basal to the HFB7 clade. Consistent with this, HFB7 was less different than HFB2 and HFB1 (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Hydropathy profiles of HFB4 (gray lines correspond to T. reesei QM6a [Tr], T. atroviride [Ta], and T. virens Gv29-8 [Tv], respectively [A]), HFB2 from T. reesei QM 6a (orange line [A and B]), and HFB7 (gray lines correspond to T. virens Gv29-8 [B]). The primary structures of all proteins are shown on the alignment between panels A and B. Hydrophobic amino acids are underlined in orange. Orange in the three-dimensional structures of HFB2 from T. reesei QM6a (PDB 2B97) indicate the respective hydrophobic amino acids. Numbered arrows indicate increased and decreased (pointing up and down, respectively) hydrophobicities of HFB4 and HFB7 compared to HFB2. The locations of these sites on the three-dimensional structure are marked with the same arrows.

This difference is also reflected in the hydropathy profiles and protein structures of HFB1, HFB2, HFB4, and HFB7 (Fig. 2): while all three proteins are mostly hydrophobic over their whole length, there are clear differences between HFB4 and HFB7 compared to HFB1 and HFB2 in distinct areas of the primary structure. Mapping them on the three-dimensional structure of HFB2 (see reference 36) shows that almost all of substitutions (labeled 2 to 6 in Fig. 2A and 7 and 8 in Fig. 2B, respectively) occur at the surface of the protein and may thus result in different surface binding behaviors of HFB2, HFB4, and HFB7.

Surface binding properties of HFB4 and HFB7.

In order to check the surface binding activities of Trichoderma HFB4 and HFB7, we overexpressed HFB4 from T. reesei, T. virens, and T. atroviride and HFB7 from T. virens as fusions to the C terminus of GST in E. coli. This approach was chosen because preliminary data showed that this leads to a highly soluble intracellular protein. We also tried to release the HFBs from GST by cleavage with thrombin to work with the pure HFBs, but this resulted in a complete loss of HFB4 and HFB7, probably due to adhesion on the walls of the vials and/or precipitation (L. Espino-Rammer, C. P. Kubicek, and I. S. Druzhinina, unpublished data). We therefore performed all of the experiments described here with the respective fusion proteins, and we also included controls using pure GST.

After purification of the GST-hydrophobin fusions by affinity chromatography on glutathione-Sepharose beads, we subjected the fusion proteins to water contact angle (WCA) measurements to determine whether the respective proteins can interact with hydrophilic or hydrophobic surfaces. Since our interest was in the hydrolysis of PET, this polymer was chosen as the hydrophobic model surface, and glass was used as a hydrophilic model substrate. The results, obtained under conditions optimal for the subsequent assay of cutinase activity on PET, are given in Table 2 (for HFB4, only the protein from T. atroviride is shown, but the proteins from T. reesei and T. virens yielded consistent results [unpublished data]). With HFB4, we observed strong binding to PET, leading to >30% reduction of the WCA. Binding of HFB4 to hydrophilic surfaces could likewise be observed. Washing the PET sheets or glass slides after incubation with the HFBs with 1% (wt/vol) SDS had no effect on the WCA results (data not shown), indicating that the binding of the HFBs is remarkably stable.

Table 2.

Surface modulating activities of HFB4 from T. atroviride and HFB7 from T. virens

| Medium | Concn (μM) | Mean surface modulating activity (degrees) ± SDa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | HFB4 | HFB7 | GST | ||

| Glass | 50 | 15.76 ± 0.81 | 31.06 ± 2.37 | 20.63 ± 0.79 | 16.98 ± 1.55 |

| 200 | 15.76 ± 0.81 | 73.80 ± 2.37 | 31.55 ± 2.69 | 18.85 ± 1.01 | |

| PET | 50 | 92.95 ± 1.46 | 69.15 ± 0.84 | 65.70 ± 1.38 | 86.98 ± 1.12 |

| 200 | 92.95 ± 1.46 | 39.96 ± 1.28 | 47.80 ± 0.69 | 94.50 ± 2.29 | |

The cconcentrations for HFB4, HFB7, or GST data are means of eight independent experiments.

HFB7 provided a different picture: whereas incubation with PET also reduced WCA to a degree similar to that observed with HFB4, the value on glass was not affected by HFB7 (Table 2). Controls performed with GST alone showed no effect (Table 2).

Hydrophobin stimulation of PET hydrolysis by cutinase.

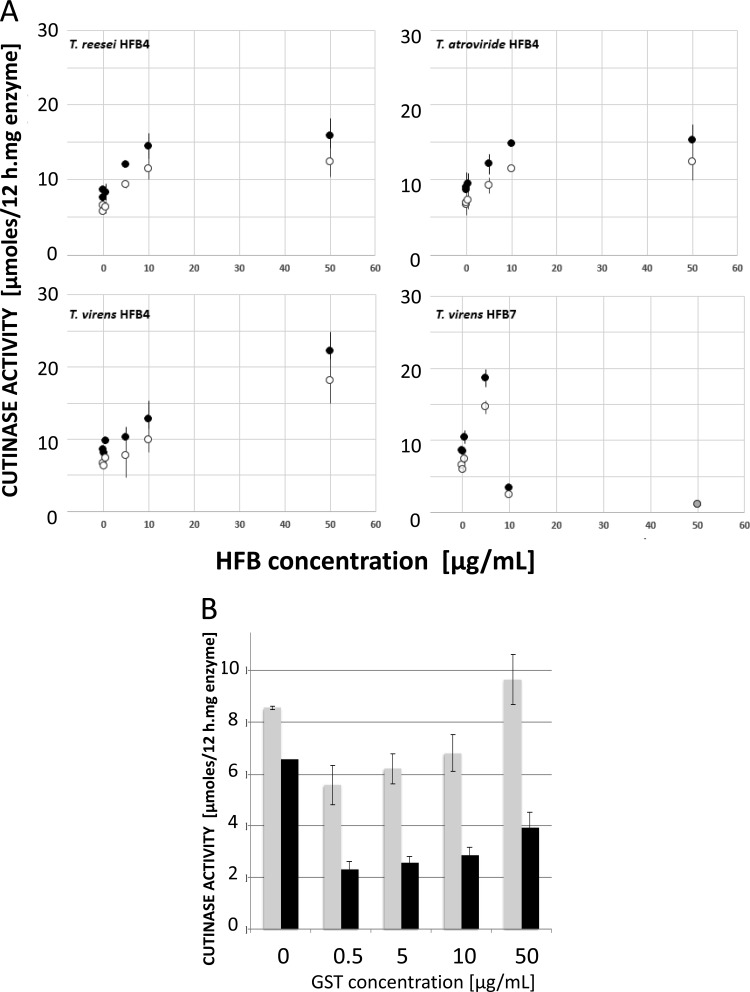

Having established that the two new HFB proteins can bind to PET, thereby altering its surface hydrophobicity, we tested whether they would be able to stimulate the activity of cutinases that hydrolyze PET. A cutinase from H. insolens (Ascomycota) was chosen for this purpose because it has previously been shown to hydrolyze PET (10, 11). Preliminary experiments, using various amounts of enzyme (i.e., enzyme activity) and different incubation times showed that PET hydrolysis is linear over the first 24 h and with an enzyme concentration between 0.1 and 1 mg/ml. Similar data have been reported before (10), and these findings are therefore not repeated here. During incubation for more than 24 h, the accumulated PET oligomers became hydrolyzed at a faster rate than PET itself. Consequently, 24 h and a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml were used throughout these experiments. As seen in Fig. 3A, the simultaneous addition of cutinase and HFB4 at concentrations from 0.05 to 50 mg/liter to PET resulted in a dosage-dependent stimulation of cutinase activity, as measured by the release of terephthalic acid (TA) and mono-(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (MHET). The ratio of TA to MHET remained constant (0.79:1) in all experiments. In this concentration range, HFB4 from T. reesei and T. atroviride lead to the highest stimulations of 2.5- and 2.4-fold over the control at A0.5 concentrations of 43 and 33 mg/liter, respectively. T. virens HFB4 yielded the highest stimulation in all of the experiments (3.4-fold at 50 mg/liter HFB4), and yet its A0.5 (120 mg/liter) was significantly higher than those of T. reesei and T. atroviride HFB4.

Fig 3.

Impact of the hydrophobins from T. reesei, T. atroviride, and T. virens on hydrolysis of PET by a cutinase from H. insolens (0.2 mg/ml) expressed as the concentration of released products mono-(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (MHET; solid symbols) and terephthalic acid (TA; open symbols). (A) PET hydrolysis is indicated as the formation of μmol of either MHET or TA per h and mg of cutinase enzyme. The control (zero values on the x axis) contained cutinase only, whereas all other samples also contained hydrophobins in the indicated concentrations. (B) Bar diagram showing the effect of GST alone on cutinase activity.

The HFB7 protein from T. virens presented a different picture: it stimulated the activity of cutinase only at a low concentration (0.5 mg/liter) 2.2- and 2.4-fold for TA and MHET, respectively, but significantly inhibited hydrolysis at higher concentrations (Fig. 3A). Free GST alone did not result in any stimulation but, in contrast, caused some inhibition of cutinase activity, which interestingly was lower at increasing concentrations of GST (Fig. 3B). However, we did not investigate this effect further.

To summarize, these data prove the ability of HFB4 and HFB7 to stimulate enzymatic hydrolysis of PET by fungal cutinase and also demonstrate a significant variability of this property between different hydrophobins.

DISCUSSION

Hydrophobins were originally detected because they enable fungi to grow at the interphase of solids or water and air, which is brought about by their assembly into amphiphilic structures on the outer fungal cell wall (37, 38). These amphiphilic properties have consequently raised considerable industrial interest in their application for the modification of surfaces and biopolymers (39–42). However, the diversity of HFBs has thus far not been taken into account: based on their solubility in solvents, hydropathy profiles and spacing between the conserved cysteines hydrophobins are traditionally grouped into class I and class II, respectively (15, 16, 36, 43), although it has recently been shown that this classification is more complex (32, 44), and there may instead be a continuum of species-specific classes. Askolin et al. (45) have shown that the properties of the class II hydrophobins HFB1 and HFB2 of T. reesei clearly differ from those reported for class I hydrophobins by forming less-stable membranes at a hydrophilic-hydrophobic interface and by not showing a change in secondary structure and ultrastructure at the water-air interface. Furthermore, these researchers also found differences between HFB1 and HFB2, i.e., HFB2 is a stronger general surface-active molecule, whereas HFB1 interacts more strongly with the hydrophobic solid Teflon.

This variability within class II HFBs is also reflected in the present results. HFB4 increased the WCA on glass and reduced it on PET, whereas HFB7 only reduced it on PET and was inactive on glass. These differences suggest that a more thorough screening of the diversity of class II hydrophobins may reveal additional functions that have not been described. We must note, however, that it is also possible that HFB7 was not correctly folded and that this is reflected in the differences in the action on glass. It will be interesting to investigate this possibility, particularly with respect to the narrow concentration range in which cutinase activation was seen for HFB7.

The recombinant production of HFBs has been achieved in filamentous fungi (46, 47), yeasts (Pichia pastoris [48]) and bacteria (E. coli [49]). The latter case often leads to HFB production in intracellular inclusion bodies, thus warranting additional unfolding/refolding steps. To bypass this, we overproduced T. reesei HFB4 and HFB7 as C-terminal fusions on GST, which resulted in a highly soluble protein. Fusion to GST was also successfully used for the overexpression of a hydrophobin from Foliota nameko (50). Our WCA analysis with the protein fusion provided values that are comparable to the amphiphilic nature of hydrophobins (15, 16, 36), thus indicating that the fusion did not alter the surface-binding properties of HFB4 and HFB7. This finding can be explained by the data of Wösten et al. (51) that the N-terminal part of the Schizophyllum commune SC3 hydrophobin is exposed at the hydrophilic side after self-assembly. Also, several class II hydrophobins are characterized by long N-terminal hydrophilic (GN-rich) extensions (19), suggesting that the core hydrophobin structure is not affected by the length of a hydrophilic N terminus. In line with these findings, a number of proteins have been expressed as fusions to the N terminus of hydrophobins without causing an effect on the binding properties of the latter (40, 52). Although the conjugation to GST and intracellular production in E. coli is unlikely to be scaled-up for the industrial level, these findings nevertheless suggest that the fusion of other hydrophilic N termini containing secretion signals to HFB4 or HFB7 may render them to be secreted in a soluble form by respective producer organisms. In addition, the natural occurrence of such hydrophilic terminal domains in HFBs (see above) suggests that they may even confer a beneficial function that needs to be investigated.

Although our binding studies were conducted under the conditions subsequently used for the cutinase assays and thus do not fully resemble the optimal conditions used to study surface binding of other hydrophobins, it is of interest to compare the behavior of HFB4 and HFB7 to that of the better-known T. reesei hydrophobins HFB1 and HFB2: whereas HFB1 stably immobilizes fusion proteins to hydrophobic surfaces, retaining the activity of the fusion partner, HFB2 has a fast off-rate that does not allow an efficient immobilization to the same surfaces (53), whereas both HFBs bind well to polar surfaces (52). In this regard, HFB4 resembles HFB1 by binding well to both types of surfaces, whereas HFB7—unlike both HFB1 and HFB2—seems to lack affinity to polar surfaces. We are now studying their mechanisms of adsorption to explain these differences.

Thus far, apart from the natural polyester cutin (24), stimulation of enzymatic hydrolysis by an HFB was only shown for a aliphatic synthetic polyester polybutylene succinate (PBSA [17]) but not for aromatic-aliphatic polyesters such as PET, which are generally more resistant. Both the cutinase and the HFB were identified in a pool of genes expressed during growth of A. oryzae on PBSA. Here, we used a different approach, which consisted of screening for evolutionarily young but conserved hydrophobins. The HFB4 and HFB7 clades, detected here, fulfilled these criteria. HFB4 is universally present in almost all Trichoderma spp. (L. Espino-Rammer and I. S. Druzhinina, unpublished data) and expressed during growth on solid medium (19). It activated cutinase hydrolysis of PET in a dosage-dependent manner, with a half-maximal stimulation at 33 to 120 mg/liter. However, considering that the molecular mass of GST is 26 kDa, whereas that of HFB4 is 9 kDa, the actual active concentration of HFB4 is only a fourth of that, theoretically reducing the A50 concentrations to 8 to 30 mg/liter. This concentration is comparable to that reported by previous studies to stimulate cutinase hydrolysis of cutin and suberin by HFB2 from T. reesei (24). However, the extent of stimulation of PET hydrolysis by HFB4 was higher (2.5-fold versus 1.4- to 1.7-fold). In contrast, stimulation of PBSA hydrolysis by the class I hydrophobin RolA was reported for 2 ng/ml, although the stimulation was only 1.3-fold (17). Improved enzymatic hydrolysis of PBSA in the presence of RolA was explained as due to a reduction of the surface tensions between the polymer substrate and the enzyme due to the bound HFB. Thus, RolA would spontaneously self-assemble and form either a mono- or an amphipathic multilayer on the PBSA surface, whereas the cutinase would then accumulate at the interface between the polymer surface and the water phase and thus exhibit increased activities on the substrate. However, in contrast to the present study, the simultaneous addition of CutL1 and RolA had no effect on PBSA degradation, and we therefore speculate that the mechanism of HFB4 and HFB7 stimulation of PET hydrolysis is different. A potential interpretation would be that the cutinases bind HFB4 like a surfactant, which is known to alter the conformation of cutinase. Such an alteration has previously been demonstrated by the binding of surfactants to Humicola insolens cutinase (54), and a stimulation of PET hydrolysis by a Fusarium solani cutinase by Triton X-100 has been demonstrated (11). The ratio between the released products TA and MHET, characteristic of every enzyme, remained constant over the whole dose-response study (at 0.79). In the case of bacterial cutinase 1 from Thermobifida cellulosilytica, the value is typically much greater than 10, whereas cutinase 2 from the same organism shows a ratio of 0.33 (9).

However, we note that the concentration of HFB4 in the reaction mixture that would result in 95% maximal stimulation is ∼20 μM for both T. reesei and T. atroviride HFB4 (using the data given in Fig. 3A and a molecular mass for HFB4 of 9 kDa), whereas the cutinase concentration in the mixture (0.2 mg/ml; molecular mass, 22 kDa) is 10 mM. Thus, a large fraction of the added cutinase cannot be stably bound to HFB4.

To summarize, we conclude that at least some class II HFBs can stimulate the activity of cutinases on PET but that individual HFBs can display different properties in this process, thus warranting a broader screening of HFBs for such industrial applications. Although the mechanism for how the new Trichoderma HFBs enhance the enzymatic hydrolysis of PET still requires detailed investigation, we expect that these findings will contribute to further exploitation of hydrophobins to assist in the enzymatic hydrolysis of aromatic-aliphatic polyesters such as PET.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Federal Ministry of Economy, Family, and Youth, the Federal Ministry of Traffic, Innovation, and Technology, the Styrian Business Promotion Agency, the Standortagentur Tirol, and the ZIT–Technology Agency of the City of Vienna through the COMET-Funding Program managed by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG.

We thank Zhilin Yuan for help in E. coli cultivation and protein purification.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Zimmermann W, Billig S. 2011. Enzymes for the biofunctionalization of poly(ethylene terephthalate). Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 125:97–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guebitz GM, Cavaco-Paulo A. 2008. Enzymes go big: surface hydrolysis and functionalisation of synthetic polymers. Trends Biotechnol. 26:32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Troev G, Grancharov G, Tsevi R, Gitsov I. 2003. A new catalyst for PET depolymerization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 90:1148–1153 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brueckner T, Eberl A, Heumann S, Rabe M, Guebitz GM. 2008. Enzymatic and chemical hydrolysis of poly(ethyleneterephthalate) fabrics. J. Polym. Sci. 46:6435–6443 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schroeder M, Fatarella E, Kovac J, Guebitz GM, Kokol V. 2008. Laccase-induced grafting on plasma-pretreated polyprene. Biomacromolecules 9:2735–2741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tkavc T, Vesel A, Herrero Acero E, Fras Zemlij L. 2013. Comparison of oxygen plasma and cutinase effect on polyethylene terephthalate surface. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 128:3570–3575 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ribitsch D, Heumann S, Trotscha E, Herrero Acero E, Greimel K, Leber R, Birner-Gruenberger R, Deller S, Eiteljoerg I, Remler P, Weber T, Siegert P, Maurer K, Donelli I, Freddi G, Schwab H, Guebitz GM. 2011. Hydrolysis of polyethyleneterephthalate by para-nitrobenzylesterase from Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnol. Prog. 27:951–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dadashian F, Montazer M, Ferdowsi S. 2010. Lipases improve grafting polyethylene terephetalate fabrics with acrylic acid. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 116:203–209 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Herrero Acero E, Ribitsch D, Steinkellner G, Gruber K, Greimel K, Eiteljoerg I, Trotscha E, Wei R, Zimmermann W, Zinn M, Cavaco-Paulo A, Freddi G, Schwab H, Guebitz GM. 2011. Enzymatic surface hydrolysis of PET: effect of structural diversity on kinetic properties of cutinases from Thermobifida. Macromolecules 44:4640–4647 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ronkvist ÅM, Xie W, Lu W, Gross RA. 2009. Cutinase-catalyzed hydrolysis of poly(ethylene terephthalate). Macromolecules 42:5128–5138 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eberl A, Heumann S, Kotek R, Kaufmann F, Mitsche S, Cavaco-Paulo A, Gübitz GM. 2008. Enzymatic hydrolysis of PTT polymers and oligomers. J. Biotechnol. 135:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buschhaus C, Jetter R. 2011. Composition differences between epicuticular and intracuticular wax substructures: how do plants seal their epidermal surfaces? J. Exp. Bot. 62:841–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pio TF, Macedo GA. 2009. Cutinases: properties and industrial applications. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 66:77–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carvalho CM, Aires-Barros MR, Cabral JM. 1999. Cutinase: from molecular level to bioprocess development. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 66:17–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Linder MB, Szilvay GR, Nakari-Setala T, Penttilä ME. 2005. Hydrophobins: the protein-amphiphiles of filamentous fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:877–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whiteford JR, Spanu PD. 2002. Hydrophobins and the interaction between fungi and plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 3:391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Takahashi T, Maeda H, Yoneda S, Ohtaki S, Yamagata Y, Hasegawa F, Gomi K, Nakajima T, Abe K. 2005. The fungal hydrophobin RolA recruits polyesterase and laterally moves on hydrophobic surfaces. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1780–1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wösten HA, de Vocht ML. 2000. Hydrophobins, the fungal coat unraveled. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1469:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kubicek CP, Baker SE, Gamauf C, Kenerley CM, Druzhinina IS. 2008. Purifying selection and birth-and-death evolution in the class II hydrophobin gene families of the ascomycete Trichoderma/Hypocrea. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:4. 10.1186/1471-2148-8-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Muñoz G, Nakari-Setälä T, Agosin E, Penttilä ME. 1997. Hydrophobin gene srh1, expressed during sporulation of the biocontrol agent Trichoderma harzianum. Curr. Genet. 32:225–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Askolin S, Penttila ME, Wösten HAB, Nakari-Setälä T. 2005. The Trichoderma reesei hydrophobin genes hfb1 and hfb2 have diverse functions in fungal development. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253:281–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Druzhinina IS, Seidl-Seiboth V, Herrera-Estrella A, Horwitz BA, Kenerley CM, Monte E, Mukherjee PK, Zeilinger S, Grigoriev IV, Kubicek CP. 2011. Trichoderma: the genomics of opportunistic success. Nat. Microbiol. Rev. 16:749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klein D, Eveleigh DE. 1998. Ecology of Trichoderma, p 57–69 In Kubicek CP, Harman GE. (ed), Trichoderma and Gliocladium, vol 1 Taylor and Francis, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kontkanen H, Westerholm-Parvinen A, Saloheimo M, Bailey M, Rättö M, Mattila I, Mohsina M, Kalkkinen N, Nakari-Setälä T, Buchert J. 2009. Novel Coprinopsis cinerea polyesterase that hydrolyzes cutin and suberin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:2148–2157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. 1997. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nicholas KB, Nicholas HB., Jr 1997. Genedoc: a tool for editing and annotating multiple sequence alignments. http://www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc. Accessed 21 August 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Swofford DL. 2002. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 4.0b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nylander JA, Wilgenbusch JC, Warren DL, Swofford DL. 2008. AWTY: a system for graphical exploration of MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylogenetics. Bioinformatics 25:581–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pail M, Peterbauer T, Seiboth B, Hametner C, Druzhinina IS, Kubicek CP. 2004. The metabolic role and evolution of l-arabinitol 4-dehydrogenase of Hypocrea jecorina. Eur. J. Biochem. 271:1864–1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Stuhl K. 2006. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates/Wiley Interscience, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seidl-Seiboth V, Gruber S, Sezerman U, Schwecke T, Albayrak A, Neuhof T, von Döhren H, Baker SE, Kubicek CP. 2011. Novel hydrophobins from Trichoderma define a new hydrophobin subclass: protein properties, evolution, regulation and processing. J. Mol. Evol. 72:339–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neuhof T, Dieckmann R, Druzhinina IS, Kubicek CP, Nakari-Setälä T, Penttilä ME, von Döhren H. 2007. Direct identification of hydrophobins and their processing in Trichoderma using intact-cell MALDI-TOF MS. FEBS J. 274:841–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martinez D, Berka RM, Henrissat B, Saloheimo M, Arvas M, Baker SE, Chapman J, Chertkov O, Coutinho PM, Cullen D, Danchin EG, Grigoriev IV, Harris P, Jackson M, Kubicek CP, Han CS, Ho I, Larrondo LF, de Leon AL, Magnuson JK, Merino S, Misra M, Nelson B, Putnam N, Robbertse B, Salamov AA, Schmoll M, Terry A, Thayer N, Westerholm-Parvinen A, Schoch CL, Yao J, Barabote R, Nelson MA, Detter C, Bruce D, Kuske CR, Xie G, Richardson P, Rokhsar DS, Lucas SM, Rubin EM, Dunn-Coleman N, Ward M, Brettin TS. 2008. Genome sequence analysis of the cellulolytic fungus Trichoderma reesei (syn. Hypocrea jecorina) reveals a surprisingly limited inventory of carbohydrate active enzymes. Nat. Biotechnol. 26:553–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kubicek CP, Herrera-Estrella A, Seidl-Seiboth V, Martinez DA, Druzhinina IS, Thon M, Zeilinger S, Casas-Flores S, Horwitz BA, Mukherjee PK, Mukherjee M, Kredics L, Alcaraz LD, Aerts A, Antal Z, Atanasova L, Cervantes-Badillo MG, Challacombe J, Chertkov O, McCluskey K, Coulpier F, Deshpande N, von Döhren H, Ebbole DJ, Esquivel-Naranjo EU, Fekete E, Flipphi M, Glaser F, Gómez-Rodríguez EY, Gruber S, Han C, Henrissat B, Hermosa R, Hernández-Oñate M, Karaffa L, Kosti I, Le Crom S, Lindquist E, Lucas S, Lübeck M, Lübeck PS, Margeot A, Metz B, Misra M, Nevalainen H, Omann M, Packer N, Perrone G, Uresti-Rivera EE, Salamov A, Schmoll M, Seiboth B, Shapiro H, Sukno S, Tamayo-Ramos JA, Tisch D, Wiest A, Wilkinson HH, Zhang M, Coutinho PM, Kenerley CM, Monte E, Baker SE, Grigoriev IV. 2011. Comparative genome sequence analysis underscores mycoparasitism as the ancestral lifestyle of Trichoderma. Genome Biol. 12:R40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sunde M, Kwan AH, Templeton MD, Beever RD, Mackay MP. 2008. Structural analysis of hydrophobins. Micron 39:773–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bayry J, Aimanianda V, Guijarro JI, Sunde M, Latgé JP. 2012. Hydrophobins: unique fungal proteins. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002700. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wösten HA. 2001. Hydrophobins: multipurpose proteins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:625–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iconomidou VA, Hamodrakas SJ. 2008. Natural protective amyloids. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 9:291–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scholtmeijer K, Janssen MI, Gerssen B, de Vocht ML, van Leeuwen BM, van Kooten TG, Wösten HA, Wessels JG. 2002. Surface modifications created by using engineered hydrophobins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1367–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scholtmeijer K, Janssen MI, van Leeuwen MB, van Kooten TG, Hektor H, Wösten HAB. 2004. The use of hydrophobins to functionalize surfaces. Biomed. Mater. Eng. 14:447–454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haas Jimoh Akanbi M, Post E, Meter-Arkema A, Rink R, Robillard GT, Wang X, Wösten HA, Scholtmeijer K. 2010. Use of hydrophobins in formulation of water insoluble drugs for oral administration. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 75:526–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wessels JGH. 1994. Developmental regulation of fungal cell wall formation. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 32:413–447 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jensen BG, Andersen MR, Pedersen MH, Frisvad JC, Sondergaard I. 2010. Hydrophobins from Aspergillus species cannot be clearly divided into two classes. BMC Res. Notes 3:344. 10.1186/1756-0500-3-344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Askolin S, Linder M, Scholtmeijer S, Tenkanen M, Penttilä M, de Vocht ML, Wösten HAB. 2006. Interaction and comparison of a class I hydrophobin from Schizophyllum commune and class II hydrophobins from Trichoderma reesei. Biomacromolecules 7:1295–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Askolin S, Nakari-Setälä T, Tenkanen M. 2001. Overproduction, purification, and characterization of the Trichoderma reesei hydrophobin HFBI. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 57:124–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schmoll M, Seibel C, Kotlowski C, Wöllert Genannt Vendt F, Liebmann B, Kubicek CP. 2010. Recombinant production of an Aspergillus nidulans class I hydrophobin (DewA) in Hypocrea jecorina (Trichoderma reesei) is promoter dependent. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 88:95–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lutterschmid G, Muranyi M, Stübner M, Vogel RF, Niessen L. 2011. Heterologous expression of surface-active proteins from barley and filamentous fungi in Pichia pastoris and characterization of their contribution to beer gushing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 147:17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morris VK, Kwan AH, Sunde M. 2012. Analysis of the structure and conformational states of DewA gives insight into the assembly of the fungal hydrophobins. J. Mol. Biol. 425:244–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kudo T, Sato Y, Tasaki Y, Hara T, Joh T. 2011. Heterogeneous expression and emulsifying activity of class I hydrophobin from Pholiota nameko. Mycoscience 52:283–287 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wösten HAB, de Vries OMH, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ, Wessels JGH. 1994. Atomic composition of the hydrophobic and hydrophilic sides of self-assembled SC3P hydrophobin. J. Bacteriol. 176:7085–7086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Grunér MS, Szilvay GR, Berglin M, Lienemann M, Laaksonen P, Linder MB. 2012. Self-assembly of class II hydrophobins on polar surfaces. Langmuir 28:4293–4300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Linder M, Szilvay GR, Nakari-Setälä T, Söderlund H, Penttilä M. 2002. Surface adhesion of fusion proteins containing the hydrophobins HFBI and HFBII from Trichoderma reesei. Protein Sci. 11:2257–2266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nielsen AD, Arleth L, Westh P. 2005. Analysis of protein-surfactant interactions-a titration calorimetric and fluorescence spectroscopic investigation of interactions between Humicola insolens cutinase and an anionic surfactant. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1752:124–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]