Abstract

Ammonia oxidation is performed by both ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB). However, the current knowledge of the distribution, diversity, and relative abundance of these two microbial groups in freshwater sediments is insufficient. We examined the spatial distribution and analyzed the possible factors leading to the niche segregation of AOA and AOB in the sediments of the Qiantang River, using clone library construction and quantitative PCR for both archaeal and bacterial amoA genes. pH and NH4+-N content had a significant effect on AOA abundance and AOA operational taxonomy unit (OTU) numbers. pH and organic carbon content influenced the ratio of AOA/AOB OTU numbers significantly. The influence of these factors showed an obvious spatial trend along the Qiantang River. This result suggested that AOA may contribute more than AOB to the upstream reaches of the Qiantang River, where the pH is lower and the organic carbon and NH4+-N contents are higher, but AOB were the principal driver of nitrification downstream, where the opposite environmental conditions were present.

INTRODUCTION

Ammonia oxidation is performed by both ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB). Since the discovery of AOA (1–3), they have been detected in most ecosystems, including marine waters (4), coral reefs (5), estuaries (6), lake sediments (7), hot springs (8), soils (9), and artificial ecosystems (10). In accord with the ubiquity of AOA, a higher abundance of the archaeal amoA gene than of its bacterial counterparts has been found in both marine (11) and terrestrial (12) ecosystems. This finding suggests that AOA play a significant role in the natural nitrification process. Despite the higher abundance of the archaeal amoA gene, the relative contributions of AOA and AOB in ammonia oxidation are still unknown, and it remains controversial whether AOA or AOB are the main driver of this enzymatic catalytic process (13–15). Accordingly, an understanding of the different factors or factor combinations leading to the niche segregation of these ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms and their responses to environmental change is essential for the prediction and control of ecosystem functions (16).

Ammonia is the substrate of ammonia oxidation, and its concentration is an essential factor in the niche separation of AOA and AOB. Martens-Habbena et al. (17) reported that the marine-isolated AOA “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus maritimus” has a much higher affinity for ammonia than cultured AOB. Generally, AOA are able to grow well, and their growth is coupled with nitrification if the concentration of ammonia is relatively low or ammonia is supplied through the mineralization of organic matter (18). However, AOB are more competitive, and the number of AOB amoA gene copies is greater than that of AOA if the concentration of ammonia is higher (13, 19). pH may also be a major driver of the niche segregation of ammonia oxidizers. He et al. (20) recently summarized the archaeal ammonia oxidation in acidic soils, stressing the competitive advantages of AOA over AOB in acidic conditions. The cultivation of “Candidatus Nitrosotalea devanaterra” has shown that AOA occur in acid soil and can convert ammonia to nitrite at a very low pH (4.0 to 5.5). However, most cultivated bacterial ammonia oxidizers do not grow below pH 6.5 (21, 22).

Organic carbon seemed to cause not only the niche segregation of AOA and AOB, but also different clusters of AOA. The growth of Nitrosopumilus maritimus (3) and “Nitrosocaldus yellowstonii” (23) is inhibited by the addition of organic compounds in very low concentrations, whereas organic carbon can enhance the growth of Nitrosomonas europaea (24) and “Nitrososphaera viennensis” (25). Moreover, salinity (26), temperature (27), dissolved oxygen (DO) levels (28), and sulfide levels (29) also contribute to the niche segregation of these two ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms. Although a series of environmental factors results in the niche segregation of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms, the exact contributions of the environmental factors are indistinguishable (30) due to the colinearity among these factors and a lack of information on geochemical parameters (31).

To date, most studies regarding the effect of different environmental factors on AOA and AOB diversity and distribution have focused on estuarine (32), soil (33), marsh (34), and marine environments (35). With the exception of studies on two freshwater lakes (36, 37), little information is available on freshwater sediments. The ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in freshwater environments are poorly understood, which can be explained by the fact that only 2% of amoA sequences deposited in GenBank were from freshwater environments (38). Nitrification in river sediments is an obligatory part of the global nitrogen cycle. Unfortunately, this process has not previously received sufficient attention. Therefore, the primary objectives of the present study were (i) to investigate the diversity and community structure of AOA and AOB in the sediments of the Qiantang River and (ii) to ascertain the principal environmental factors leading to the niche segregation of AOA and AOB in the sediments of the Qiantang River.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site description and sediment collection.

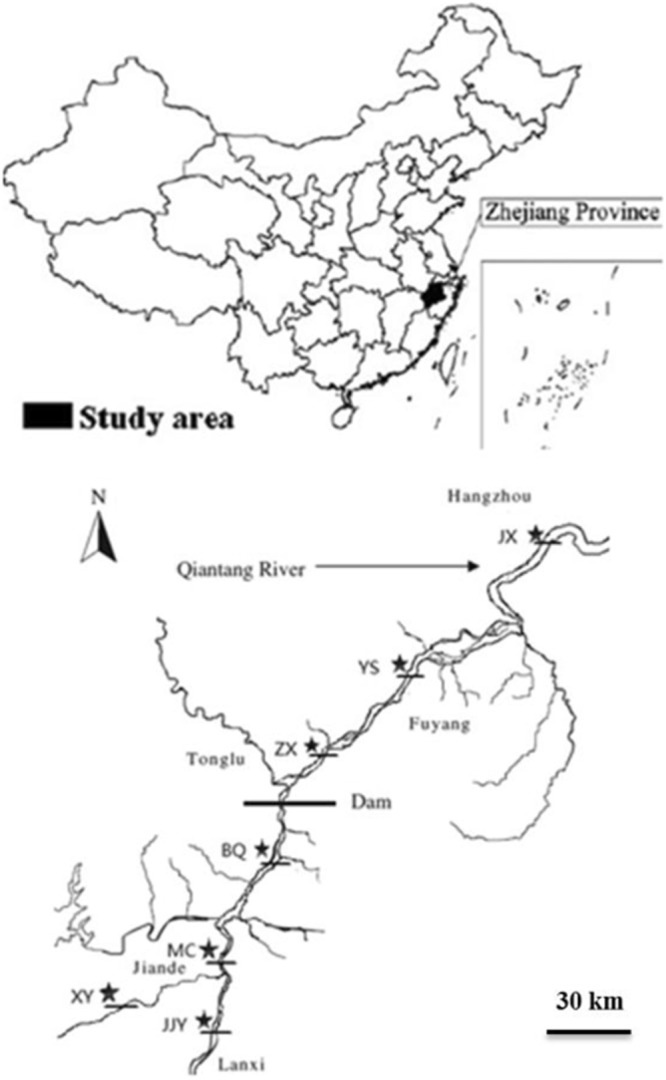

The Qiantang River is a major river system in Zhejiang Province in southeastern China (28.17° N to 30.48° N and 117.62° E to 121.87° E) (Fig. 1). The total length of the river is 688 km, and the area of its watershed is 55,600 km2. The Qiantang River is the main source of industrial, agricultural, and domestic water supplies for Zhejiang Province. The sampling sites used in this study were documented previously (39) (Fig. 1), as the environmental protection administration of Zhejiang Province had fixed monitoring sites there. Sediments were obtained using box cores, and the top 3 cm of these sediments were carefully collected. Each sediment sample was split into two equal parts: one for DNA isolation (stored at −80°C), and another for chemical analyses (stored at −4°C) (Table 1).

Fig 1.

Study area and sediment sampling sites in the Qiantang River (Reprinted from reference 39 with permission from the Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd.).

Table 1.

Physical and chemical characteristics of the sediments collected from the Qiantang Rivera

| Sampling site | pH | Concn of: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Org C (g kg−1) | TN (mg kg−1) | Org N (mg kg−1) | TIN (mg kg−1) | NH4+-N (mg kg−1) | NO3−-N (mg kg−1) | ||

| JX | 7.9 | 18.9 | 623.8 | 583.5 | 52.6 | 52.0 | 0.4 |

| YS | 8.0 | 13.4 | 480.3 | 438.7 | 41.6 | 41.0 | 0.6 |

| ZX | 8.1 | 20.2 | 173.8 | 136.5 | 37.4 | 37.0 | 0.4 |

| BQ | 6.5 | 22.4 | 571.0 | 387.5 | 183.6 | 182.0 | 1.6 |

| MC | 7.2 | 34.2 | 561.3 | 503.7 | 57.6 | 54.0 | 3.6 |

| XY | 6.1 | 26.3 | 1,491.6 | 1,385.6 | 105.9 | 89.0 | 16.9 |

| JJY | 6.9 | 31.5 | 1,274.1 | 1,177.5 | 96.6 | 96.0 | 0.6 |

Org, organic; TN, total nitrogen; TIN, total inorganic nitrogen.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification.

DNA was extracted using a Power Soil DNA kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted DNA was examined in 1.0% agarose gels by electrophoresis.

To detect AOA in the sediments, Arch-amoAF and Arch-amoAR were used to amplify 635 bp of the open reading frame (ORF) of archaeal ammonia monooxygenase subunit A (amoA) gene, as designed and suggested by Francis et al. (4). Similarly, AOB were detected using amoA-1F and amoA-2R (40), which targeted 491 bp of the bacterial amoA gene. The diversity of AOA might be underestimated to some extent due to the limitation of primer pair arch-amoAF/arch-amoAR. “Nitrosocaldus yellowstonii”-, “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus maritimus”-, and “Cenarchaeum symbiosum”-related sequences might be missing due to the limitation of the primer. The same might be happen in bacterial amoA gene amplification. The PCR thermal cycling programs employed for both AOA and AOB have been described previously (41). The amplified products were examined in a 1.0% agarose gel with electrophoresis.

Cloning and sequencing.

PCR products were purified and cloned using the pMD19-T vector (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid DNA was isolated with a Gene JET plasmid miniprep kit (Fermentas Life Sciences, Germany). Plasmids were digested with 5U EcoRI enzyme in EcoRI buffer for 1.5 h at 37°C, and the products were examined for an insertion of the expected size by agarose (1.0%) gel electrophoresis. At least 25 positive clones in each library were randomly selected for sequencing on an ABI3100 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, CA).

Phylogenetic analyses.

The amoA gene sequences obtained were imported into the MEGA4.1 program to construct alignment files in combination with the sequences of known strains of AOA and AOB. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method. A bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates was applied to estimate the confidence values for the tree nodes.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR).

The primer sets described above were used to quantify the copy numbers of amoA genes of AOA and AOB present in the samples. The copy numbers of both AOA and AOB might be underestimated due to the limitation of the primers. qPCR was performed using an iCycler iQ5 thermocycler and a real-time detection system (Bio-Rad, CA) as previously described (42). After different dilutions of extracted DNA had been tested for inhibitory effects by coextracted compounds, 1 to 5 ng of template DNA was used in each 25-μl PCR. Standard curves for AOA and AOB were constructed from a series of 10-fold dilutions of plasmid DNA containing insertions of amoA genes from AOA and AOB.

Statistical analysis.

Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were used to determine the archaeal and bacterial amoA gene diversity in different soil samples. For both AOA and AOB, researchers have found that a 1% to 3% 16S rRNA distance equates to a 15% amoA gene distance (43, 44). An 85% sequence identity at the amoA gene level can be considered an approximate threshold below which ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms can be assigned to different species. Hence, OTUs were defined by 15% differences for both the archaeal amoA gene and the bacterial amoA gene in nucleotide sequences. OTU numbers were determined with the farthest-neighbor algorithm in the DOTUR program (45).

The coverage of the clone libraries was calculated as [1 − (n1/N)] × 100, where n1 is the number of unique OTUs and N is the total number of clones in a library. DOTUR was also used to generate a Shannon index for each clone library. The ecological distribution of the AOA and AOB communities and their correlations with environmental factors were determined with a principal components analysis (PCA) and a redundancy analysis (RDA), respectively, using CANOCO software. In addition, a Pearson correlation analysis (significance level [α] = 0.05) was used to test for correlations between the AOA and AOB diversity, abundance, and environmental factors.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KC537388 to KC537423.

RESULTS

Abundance, community structure, and composition changes of AOA and AOB along the Qiantang River sediment (from upstream to downstream).

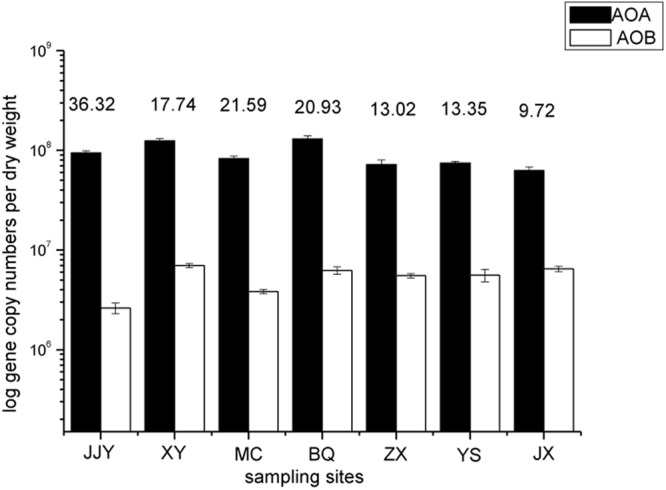

In the present study, seven sampling sites along the river were selected, and the functional genes (amoA genes) for ammonia oxidation of AOA and AOB were quantified. AOA dominated numerically at all seven sites and were up to one order of magnitude more abundant than AOB. The number of AOA amoA genes ranged from 6.28 × 107 to 1.30 × 108 copies per g of dry sediment, whereas the AOB amoA genes ranged from 2.61 × 106 to 6.99 × 106 copies per g of dry sediment. The ratio of AOA/AOB varied from 9.72 at site JX to 36.32 at JJY (Fig. 2). The number of AOA amoA genes varied greatly (P = 0.039) from upstream to downstream in the Qiantang River. At the upstream sites (JJY, XY, MC, and BQ), the AOA amoA gene copy numbers were all above 8.27 × 107 copies per g of dry sediment; however, the values were all below 7.46 × 107 copies per g of dry sediment at the downstream sites (ZX, YS, and JX). The ratio of AOA/AOB amoA gene copy numbers showed the same regular pattern (with P = 0.060), ranging from 17.74 to 36.32 at the upstream sites and 9.72 to 13.02 at the downstream sites.

Fig 2.

Quantitative analysis of AOA and AOB at seven sampling sites along the Qiantang River. The ratio of AOA to AOB gene copy numbers is shown above the histogram.

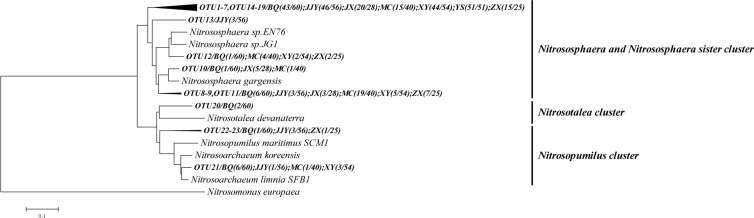

Based on the 15% cutoff recommended in a previous study (43), the 314 sequences of AOA amoA genes were assigned to 23 OTUs, most of which included more than one sequence from different sites. According to the newly developed system of nomenclature for archaeal amoA genes (43), all of the obtained OTUs were grouped into three different clusters (Fig. 3). The Nitrosopumilus cluster contained 3 OTUs, and the Nitrosotalea cluster contained only 1 OTU. The remaining OTUs belonged to the Nitrososphaera and Nitrososphaera sister cluster. Among the 314 archaeal amoA sequences retrieved, 296 sequences from all seven sites were affiliated with the Nitrososphaera and Nitrososphaera sister cluster. These groupings represented 94.3% of all the archaeal amoA sequences obtained. The Nitrosotalea cluster and the Nitrosopumilus contained 0.64% and 5.10% of all the sequences obtained. The numbers of detected OTUs per clone library ranged from 6 to 15 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Remarkable diversity changes and heterogeneous community structures were found for AOA from the upstream sites to the downstream sites along the river. The downstream sites (ZX, YS, and JX) included 6 OTUs, fewer than the number (ranging from 9 to 15) detected at the 4 upstream sampling sites (see Table S1). The sequences detected at the downstream sites (YS and JX) belonged to one cluster (the Nitrososphaera and Nitrososphaera sister cluster). The five upstream sites contained sequences belonging to at least two clusters (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Fig 3.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree showing the phylogenetic affiliations of AOA amoA gene sequences recovered from the Qiantang River. The numbers at the nodes are percentages that indicate the levels of bootstrap support (1,000 replicates). The scale bar represents 0.1 nucleic acid substitution per nucleotide position.

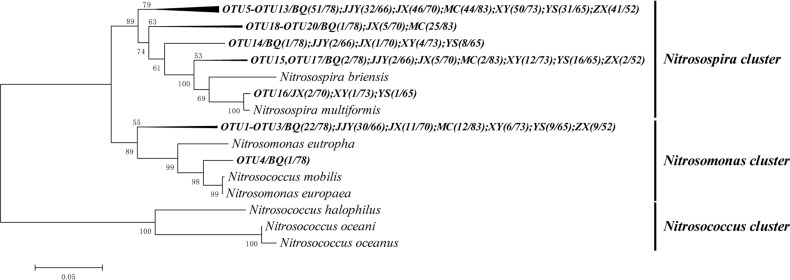

For AOB, 488 sequences were obtained. These sequences were clustered into 20 OTUs, with 85% similarity for each OTU, as previously predicted (44). All of the OTUs obtained were grouped into two clusters, with OTU1 to OTU4 being grouped in the Nitrosomonas cluster and OTU5 to OTU20 in the Nitrosospira cluster (Fig. 4). In all, 8 to 13 OTUs were detected for each clone library (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Differences in diversity similar to those found for AOA were also found for AOB along the Qiantang River (from upstream to downstream). The downstream sites YS and JX showed the highest diversity, with 13 OTUs in each clone library, a value higher than that found for the other five sites (see Table S1). The community structure changed along the Qiantang River. The proportion occupied by the Nitrosomonas cluster at site JJY (upstream) was much higher than the proportions at the remaining sampling sites (Fig. S2).

Fig 4.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree showing the phylogenetic affiliations of AOB amoA gene sequences recovered from the Qiantang River. The numbers at the nodes are percentages that indicate the levels of bootstrap support (1,000 replicates). The scale bar represents 0.05 nucleic acid substitution per nucleotide position.

Moreover, the ratio of the AOA and AOB OTU numbers changed from upstream to downstream. The AOA showed a higher diversity at the upstream sites, where the ratio of AOA/AOB OTU numbers was 1.56. However, this ratio decreased linearly (r2 = 0.78) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) to 0.46 at sites YS and JX, where the AOB diversity was higher.

Environmental factors shaping the niche segregation of AOA and AOB along the Qiantang River (from upstream to downstream).

The linear relationships between different environmental factors and the amoA gene abundance, OTU numbers, and diversity index of AOA and AOB were characterized using the Pearson correlation coefficient, as shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The AOA amoA gene copy numbers were significantly negatively correlated with pH (P < 0.01) and positively correlated with NH4+-N (i.e., the nitrogen present in ammonium) (P < 0.05). The AOA OTU numbers were significantly positively correlated with total inorganic nitrogen (TIN) and NH4+-N (P < 0.01) but negatively correlated with pH (P < 0.01). The AOA Shannon index and Chao index were negatively correlated with pH (P < 0.05). The AOB OTU numbers were significantly negatively correlated with the content of organic carbon (P < 0.01). Additionally, the ratio of AOA/AOB OTU numbers was positively correlated with the content of organic carbon (P < 0.05) but negatively correlated with pH (P < 0.05) in the sediments.

Differences in AOA and AOB community structures were observed at different sampling sites from Qiantang River sediments by the principal component analysis (PCA) using CANOCO software based on the amoA gene sequences of AOA and AOB (see Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). The results showed that the AOA communities at site YS differed significantly from the others. The dominant OTU in YS was OTU4. At the other six sites, the dominant OTUs were OTU1 and OTU9. The AOA communities at sites JX and ZX were highly similar and fell into the same group. Similarly, differences in community structures were also observed for AOB at all the sampling sites. The AOB community structures at sites BQ, JX, and ZX were highly similar, and all of these sites were dominated by OTU5. The community structure varied among the other four sites. The heterogeneous community structure of AOA and AOB found in different samples may be related to the various environmental conditions at different sampling sites.

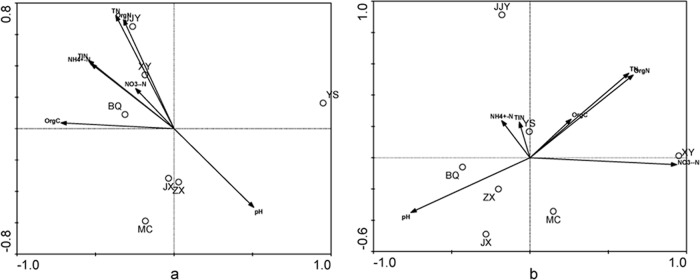

To identify the potential relationship between the community structure of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms and environmental factors in the Qiantang River sediments, a redundancy analysis (RDA) with CANOCO software was conducted based on the AOA and AOB community structures and the data on the environmental factors (Fig. 5). Generally, RDA was chosen to determine the relationships between the AOA and AOB community structures and the environmental factors because the longest gradient in a detrended correspondence analysis was shorter than 3.0 (46). The community structure analysis of AOA and AOB based on the RDA was consistent with the results of the PCA, as shown in Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material. pH showed a negative effect on the population composition at sites XY, BQ, and JJY. The population composition of BQ was positively correlated with NH4+-N and organic carbon content, whereas the population composition of XY and JJY was positively correlated with organic nitrogen and total nitrogen content. The AOB population composition in sample XY was positively correlated with NO3−-N, and pH showed a positive effect on the population composition of BQ, ZX, and JX. Of all the environmental factors investigated, the NO3−-N content appeared to be the most significant influence on the community distributions of AOB in the sediments of the Qiantang River (P < 0.05). The organic nitrogen content and pH also contributed to the AOB-environment relationship in the Qiantang River sediments, although the significance level was lower (P < 0.10). Moreover, organic carbon had an effect on the community distributions of AOA at a lower significance level (P < 0.10).

Fig 5.

RDA ordination plots for the first dimension to show the relationship between the AOA (a) and AOB (b) communities and environmental factors. Correlations between environmental factors and RDA axes are represented by the length and angle of arrows.

DISCUSSION

Very few studies have focused on the ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in freshwater sediments. This study is the first investigation and evaluation of the diversity, population composition, and impact factors of AOA and AOB along the Qiantang River (from upstream to downstream). A quantitative analysis indicated that AOA were predominant at all seven sampling sites along the river. Wu et al. (37) reported that AOA outnumbered AOB in almost all of the sediments of Lake Taihu and that the ratios of these two ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms ranged from 3.0 to 153. Similarly, the findings of the present study showed a ratio of AOA/AOB ranging from 9.72 to 36.32. Archaeal and bacterial amoA genes were also detected and quantified in another freshwater lake, where the archaeal amoA gene was up to 3 orders of magnitude more abundant than the bacterial amoA gene (36). These higher ratios may be explained by the presence of secretions by macrophyte species, as verified previously (7). AOA appeared to be the primary driver of ammonia oxidation in the Qiantang River due to the higher abundance of archaeal amoA gene. However, abundance data must be interpreted cautiously. The presence or high abundance of a functional gene does not mean that the gene is being expressed. A functional gene might be expressed only under rare combinations of environmental conditions, and the amoA gene product may provide alternative ecosystem functions to ammonia oxidation (in both bacteria and archaea) (47).

The phylogenetic analysis of the AOA amoA genes in the sediment showed that most of the detected sequences (85.0%-100.0%) in the seven sampling sites were affiliated with the Nitrososphaera and Nitrososphaera sister cluster. The data must be interpreted cautiously, since some marine and thermophilic AOA might be missing due to the bias of the primer. This result was consistent with a previous study focused on amoA gene diversity and distribution at a global scale (43). It appears that AOA belonging to this subcluster may play a significant role in ammonia oxidation in the sediments of the Qiantang River. Sequences affiliated with the Nitrosotalea cluster were detected only at site BQ, where the pH was 6.5. This phenomenon appears to contradict the findings of a previous study (48) that demonstrated that the acidophilic AOA “Candidatus Nitrosotalea devanaterra” grew at an optimal pH ranging from 4 to 5 and was totally inhibited if the pH increased to 6. In fact, the similarities between the “Candidatus Nitrosotalea devanaterra” amoA gene and the two amoA gene sequences belonging to the acidophilic AOA cluster were 74.1% and 74.3%, lower than the threshold (85% similarity) that distinguishes different species (43). This finding indicates that there may exist new species affiliated with the Nitrosotalea cluster that can withstand a relatively greater pH (pH > 6.0). Two clusters of AOB were found along the river. The proportions of the Nitrosomonas cluster at sites BQ and JJY were much greater than those at the other five sampling sites. Correspondingly, the content of NH4+-N at these two sites was higher. This result might be explained by differences in physiological characteristics between Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira. Schramm et al. (49, 50) have reported that the growth of Nitrosomonas species followed an R strategy. Nitrosomonas had a low ammonia affinity and was adapted to conditions where the concentration of ammonia was high. In contrast, the growth of Nitrosospira species followed a K strategy. Nitrosospira had a high ammonia affinity and was adaptable to conditions where the concentration of ammonia was low.

Our results demonstrated that in the Qiantang River sediment we investigated, the trend of AOA abundance was consistent with its diversity, as well as AOB. The Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated that AOA amoA gene copy numbers were significantly negatively correlated with sediment pH (r2 = −0.8623, P < 0.01) along the Qiantang River (from upstream to downstream). The same regular pattern was also found for AOA OTU numbers (r2 = −0.7758, P < 0.01). At the upstream sampling sites, where the sediment pH was neutral or slightly acidic (the pH ranged from 6.1 to 7.2), the AOA amoA gene copy numbers were greater than 8.27 × 107 and the AOA OTU numbers were greater than 9; however, both AOA amoA gene copy numbers and OTU numbers decreased at the downstream sites, where the soil pH increased to alkaline levels (the pH ranged from 7.9 to 8.1). The ratio of AOA to AOB OTU numbers also changed along the Qiantang River and showed a significant negative correlation with pH (P < 0.05). At the upstream sites, where neutral or slightly acidic conditions are found, the AOA diversity was higher than the AOB diversity. At the downstream sites, which are alkaline, the situation was the opposite, and the ratio of AOA/AOB OTU numbers was below 1. The AOA/AOB amoA gene copy numbers changed in a way similar to the ratio of AOA/AOB OTU numbers. These results showed that AOA had a competitive advantage over AOB under conditions with a low pH. Culture-based approaches had already shown that no ammonia-oxidizing bacteria could survive at a pH below 6.5 (21, 22) but that ammonia-oxidizing archaea, such as “Candidatus Nitrosotalea devanaterra,” could convert ammonia to nitrite at a pH of 4.5 (48).

Other studies have also demonstrated that ammonia-oxidizing archaea are more tolerant to low pH than AOB and that AOA are primarily responsible for nitrification in acidic soils (51, 52). Moreover, the decreased pH may reduce the bioavailability of ammonia. These conditions favored the growth of AOA, because the affinity of AOA for ammonia was much higher than that of their substrate competitors, AOB (17). For this reason, it was not surprising that the AOA amoA gene copy numbers, the AOA OTU numbers, the ratio of AOA/AOB amoA gene copy numbers, and the ratio of AOA/AOB OTU numbers decreased with increasing pH along the Qiantang River (from upstream to downstream), exhibiting a spatial change along the Qiantang River and indicating that AOA may be more important than AOB at the upstream sites, where the pH was relatively lower in our study.

Similarly to the pH, the changes in AOA amoA gene copy numbers and AOA diversity influenced by the NH4+-N content also exhibited an obvious spatial trend along the Qiantang River (from upstream to downstream). A Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated that both AOA amoA copy numbers and AOA OTU numbers were significantly positively correlated with NH4+-N content (r2 = 0.7226, P < 0.05; r2 = 0.7663, P < 0.01). At the upstream sites, where the NH4+-N content was higher (ranging from 54 to 182 mg/kg), the AOA amoA copy numbers and AOA OTU numbers were also higher. At the downstream sites, where the NH4+-N content was lower (<52 mg/kg), the situation was the opposite. These results appear to contradict the principle that ammonia-oxidizing archaea prefer conditions where the ammonia concentration is relatively low. Given that more than 90% of the sequences detected in our study belonged to the Nitrososphaera and Nitrososphaera sister cluster, our results are reasonable, because the ammonia-oxidizing archaea in this cluster had a relatively lower affinity for ammonia than the AOA affiliated with the Nitrosopumilus cluster and Nitrosotalea cluster and could withstand a relatively high ammonia concentration. “Nitrososphaera viennensis” strain EN76 was found to grow well in media containing ammonium concentrations as high as 15 mM, and its growth was inhibited at 20 mM (25). The inhibition concentration of ammonia for “Nitrosoarchaeum koreensis” strain MY1 (53) and “Candidatus Nitrososphaera” sp. strain JG1 was found to be nearly 20 mM (54). Moreover, the highest NH4+-N content in our study was 182 mg/kg, equal to approximately 17.33 mM (the average moisture content was 75% in this study), lower than the inhibition concentration of ammonia. Overall, the AOA amoA copy numbers and AOA diversity decreased with decreasing NH4+-N content from upstream to downstream in the Qiantang River sediments.

Another environmental factor that influenced the ratio of the AOA/AOB OTU numbers was organic carbon. At the upstream sites, where the organic carbon content was higher (ranging from 22.4 to 34.2 g/kg), the AOA amoA gene diversity was higher than that of AOB. The opposite situation was found for the organic carbon content (ranging from 13.4 to 20.2 g/kg) at the downstream sites. Although organic carbon has been reported to inhibit the growth of certain AOA, such as “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus maritimus” (3), which was affiliated with the Nitrosopumilus cluster, the growth of “Nitrososphaera viennensis,” belonging to the Nitrososphaera and Nitrososphaera sister cluster, can be enhanced by adding small amounts of pyruvate (25). Chen (55) has reported a higher abundance of AOA in the paddy rhizosphere than in nonrhizosphere soil, presumably due to the organic carbon of root exudates, indicating that AOA prefer conditions with relatively large amounts of organic carbon. Moreover, most of the sequences detected in the present study belonged to the Nitrososphaera and Nitrososphaera sister cluster. For this reason, it was not surprising that the relative diversity of AOA was higher where the organic carbon content was high. Moreover, because organic carbon can enhance the growth of Nitrosomonas europaea (24), it was unclear why the AOB OTU numbers were negatively correlated with the organic carbon content.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the Natural Science Foundation (no. 41276109).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 April 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00543-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Venter JC, Remington K, Heidelberg JF, Halpern AL, Rusch D, Eisen JA, Wu DY, Paulsen I, Nelson KE, Nelson W, Fouts DE, Levy S, Knap AH, Lomas MW, Nealson K, White O, Peterson J, Hoffman J, Parsons R, Baden-Tillson H, Pfannkoch C, Rogers YH, Smith HO. 2004. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science 304:66–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Treusch AH, Leininger S, Kletzin A, Schuster SC, Klenk HP, Schleper C. 2005. Novel genes for nitrite reductase and Amo-related proteins indicate a role of uncultivated mesophilic crenarchaeota in nitrogen cycling. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1985–1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Könneke M, Bernhard AE, de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Waterbury JB, Stahl DA. 2005. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 437:543–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Francis CA, Roberts KJ, Beman JM, Santoro AE, Oakley BB. 2005. Ubiquity and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in water columns and sediments of the ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:14683–14688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beman JM, Roberts KJ, Wegley L, Rohwer Francis FCA. 2007. Distribution and diversity of archaeal ammonia monooxygenase genes associated with corals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5642–5647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beman JM, Francis CA. 2006. Diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in the sediments of a hypernutrified subtropical estuary: Bahia del Tobari, Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:7767–7777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Herrmann M, Saunders AM, Schramm A. 2008. Archaea dominate the ammonia-oxidizing community in the rhizosphere of the freshwater macrophyte Littorella uniflora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3279–3283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reigstad LJ, Richter A, Daims H, Urich T, Schwark L, Schleper C. 2008. Nitrification in terrestrial hot springs of Iceland and Kamchatka. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 64:167–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leininger S, Urich T, Schloter M, Schwark L, Qi J, Nicol GW, Prosser JI, Schuster SC, Schleper C. 2006. Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils. Nature 442:806–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Limpiyakorn T, Sonthiphand P, Rongsayamanont C, Polprasert C. 2011. Abundance of amoA genes of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in activated sludge of full-scale wastewater treatment plants. Biores. Technol. 102:3694–3701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wuchter C, Abbas B, Coolen MJL, Herfort L, van Bleijswijk J, Timmers P, Strous M, Teira E, Herndl GJ, Middelburg JJ, Schouten S, Damsté JSS. 2006. Archaeal nitrification in the ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12317–12322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He JZ, Shen JP, Zhang LM, Zhu YG, Zheng YM, Xu MG, Di HJ. 2007. Quantitative analyses of the abundance and composition of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing archaea of a Chinese upland red soil under long-term fertilization practices. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2364–2374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Di HJ, Cameron KC, Shen JP, Winefield CS, O'Callaghan M, Bowatte S, He JZ. 2009. Nitrification driven by bacteria and not archaea in nitrogen-rich grassland soils. Nat. Geosci. 2:621–624 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jia ZJ, Conrad R. 2009. Bacteria rather than Archaea dominate microbial ammonia oxidation in an agricultural soil. Environ. Microbiol. 11:1658–1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gubry-Rangin C, Nicol GW, Prosser JI. 2010. Archaea rather than bacteria control nitrification in two agricultural acidic soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 74:566–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gubry-Rangin C, Hai B, Quince C, Engel M, Thomson BC, James P, Schloter M, Griffiths RI, Prosser JI, Nicol GW. 2011. Niche specialization of terrestrial archaeal ammonia oxidizers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:21206–21211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martens-Habbena W, Berube PM, Urakawa H, de la Torre JR, Stahl DA. 2009. Ammonia oxidation kinetics determine niche separation of nitrifying Archaea and Bacteria. Nature 461:976–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Höfferle Š, Nicol GW, Pal L, Hacin J, Prosser JI, Mandić-Mulec I. 2010. Ammonium supply rate influences archaeal and bacterial ammonia oxidizers in a wetland soil vertical profile. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 74:302–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verhamme DT, Prosser JI, Nicol GW. 2011. Ammonia concentration determines differential growth of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms. ISME J. 5:1067–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He J-Z, Hu H-W, Zhang L-M. 2012. Current insights into the autotrophic thaumarchaeal ammonia oxidation in acidic soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 55:146–154 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Allison SM, Prosser JI. 1991. Urease activity in neutrophilic autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria isolated from acid soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 23:45–51 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jiang QQ, Bakken LR. 1999. Comparison of Nitrosospira strains isolated from terrestrial environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 30:171–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Ingalls AE, Könneke M, Stahl DA. 2008. Cultivation of a thermophilic ammonia oxidizing archaeon synthesizing crenarchaeol. Environ. Microbiol. 10:810–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hommes NG, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Arp DJ. 2003. Chemolithoorganotrophic growth of Nitrosomonas europaea on fructose. J. Bacteriol. 185:6809–6814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tourna M, Stieglmeier M, Spang A, Könneke M, Schintlmeister A, Urich T, Engel M, Schloter M, Wagner M, Richter A, Schleper C. 2011. Nitrososphaera viennensis, an ammonia oxidizing archaeon from soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:8420–8425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mosier AC, Francis CA. 2008. Relative abundance and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in the San Francisco Bay estuary. Environ. Microbiol. 10:3002–3016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tatsunori N, Koji M, Chiaki K, Reiji T, Tatsuaki Y. 2007. Distribution of cold-adapted ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in the deep-ocean of the northeastern Japan Sea. Microbes Environ. 22:356–372 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Santoro AE, Francis CA, de Sieyes NR, Boehm AB. 2008. Shifts in the relative abundance of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea across physicochemical gradients in a subterranean estuary. Environ. Microbiol. 10:1068–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caffrey JM, Bano N, Kalanetra K, Hollibaugh JT. 2007. Ammonia oxidation and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea from estuaries with differing histories of hypoxia. ISME J. 1:660–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dang H, Zhang X, Sun J, Li T, Zhang Z, Yang G. 2008. Diversity and spatial distribution of sediment ammonia-oxidizing crenarchaeota in response to estuarine and environmental gradients in the Changjiang Estuary and East China Sea. Microbiology 154:2084–2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Agogué H, Brink M, Dinasquet J, Herndl GJ. 2008. Major gradients in putatively nitrifying and non-nitrifying Archaea in the deep North Atlantic. Nature 456:788–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bernhard AE. 2010. Abundance of ammonia-oxidizing Archaea and Bacteria along an estuarine salinity gradient in relation to potential nitrification rates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:1285–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang LM, Wang M, Prosser JI, Zheng YM, He JZ. 2009. Altitude ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in soils of Mount Everest. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 70:52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moin NS, Nelson KA, Bush A, Bernhard AE. 2009. Distribution and diversity of archaeal and bacterial ammonia oxidizers in salt marsh sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7461–7468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ward BB, Eveillard D, Kirshtein JD, Nelson JD, Voytek MA, Jackson GA. 2007. Ammonia-oxidizing bacterial community composition in estuarine and oceanic environments assessed using a functional gene microarray. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2522–2538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Herrmann M, Saunders AM, Schramm A. 2009. Effect of lake trophic status and rooted macrophytes on community composition and abundance of ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in freshwater sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:3127–3136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu YC, Xiang Y, Wang JJ, Zhong JC, He JZ, Wu QLL. 2010. Heterogeneity of archaeal and bacterial ammonia-oxidizing communities in Lake Taihu, China. Environ. Microbiol. Reports 2:569–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kim OS, Junier P, Imhoff JF, Witzel KP. 2008. Comparative analysis of ammonia monooxygenase (amoA) genes in the water column and sediment-water interface of two lakes and the Baltic Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 66:367–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu BL, Shen LD, Zheng P, Hu AH, Chen TT, Cai C, Liu S, Lou LP. 2012. Distribution and diversity of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria in the sediments of the Qiantang River. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 4:540–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rotthauwe JH, Witzel K-P, Liesack W. 1997. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4704–4712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shen JP, Zhang LM, Zhu YG, Zhang JB, He JZ. 2008. Abundance and composition of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing archaea communities of an alkaline sandy loam. Environ. Microbiol. 10:1601–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hu BL, Liu S, Shen LD, Zheng P, Xu XY, Lou LP. 2012. Effect of different ammonia concentrations on community succession of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in a simulated paddy soil column. PLoS One 7:e44122. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pester M, Rattei T, Flechl S. 2012. amoA-based consensus phylogeny of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and deep sequencing of amoA genes from soils of four different geographic regions. Environ. Microbiol. 14:525–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Purkhold U, Pommerening-Roser A, Juretschko S, Schmid MC, Koops HP, Wagner M. 2000. Phylogeny of all recognized species of ammonia oxidizers based on comparative 16S rRNA and amoA sequence analysis: implications for molecular diversity surveys. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5368–5382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schloss PD, Handelsman J. 2005. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1501–1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lepš J, Šmilauer P. 2003. Multivariate analysis of ecological data using CANOCO. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 47. Prosser JI, Nicol GW. 2008. Relative contributions of archaea and bacteria to aerobic ammonia oxidation in the environment. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2931–2941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lehtovirta-Morley LE, Stoecker K, Vilcinskas A, Prosser JI, Nicol GW. 2011. Cultivation of an obligate acidophilic ammonia oxidizer from a nitrifying acid soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:15892–15897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schramm A, de Beer D, Wagner M, Amann R. 1998. Identification and activities in situ of nitrosospira and nitrospira spp.as dominant populations in a nitrifying fluidized bed reactor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3480–3485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schramm A, de Beer D, van den Heuvel JC, Ottengraf S, Amann R. 1999. Microscale distribution of populations and activities of Nitrosospira and Nitrospira spp. along a macroscale gradient in a nitrifying bioreactor quantification by in situ hybridization and the use of microelectrodes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3690–3696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang LM, Hu HW, Shen JP, He JZ. 2012. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea have more important role than ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in ammonia oxidation of strongly acidic soils. ISME J. 6:1032–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Isobe K, Koba K, Suwa Y, Ikutani J, Fang YT, Yoh M, Mo JM, Otsuka S, Senoo K. 2012. High abundance of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in acidified subtropical forest soils in southern China after long-term N deposition. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 80:193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jung MY, Park SJ, Min D, Kim JS, Rijpstra WIC, Sinninghe Damste JS, Kim GJ, Madsen EL, Rhee SK. 2011. Enrichment and characterization of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing archaeon of mesophilic crenarchaeal group I.1a from an agricultural soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:8635–8647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim JG, Jung MY, Park SJ, Rijpstra WIC, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Madsen EL, Min D, Kim JS, Kim GJ, Rhee SK. 2012. Cultivation of a highly enriched ammonia-oxidizing archaeon of thaumarchaeotal group I. 1b from an agricultural soil. Environ. Microbiol. 14:1528–1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chen XP, Zhu YG, Xia Y, Shen JP, He JZ. 2008. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea: important players in paddy rhizosphere soil? Environ. Microbiol. 10:1978–1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.