Abstract

ω-Transaminases display complicated inhibitions by ketone products and both enantiomers of amine substrates. Here, we report the first example of ω-transaminase devoid of such inhibitions. Owing to the lack of enzyme inhibitions, the ω-transaminase from Ochrobactrum anthropi enabled efficient kinetic resolution of α-methylbenzylamine (500 mM) even without product removal.

TEXT

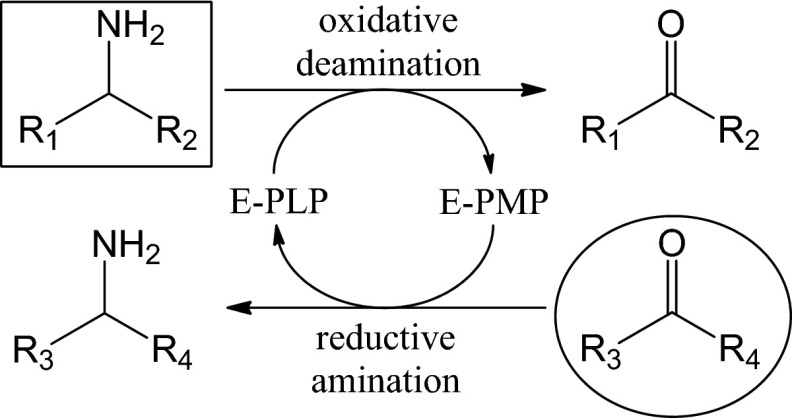

Omega-transaminase (ω-TA) catalyzes reversible transfer of an amino group between primary amines and carbonyl compounds which is mediated by pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) bound to the enzyme as a prosthetic group (1, 2). During the last decade, ω-TA has gained increasing attention for chiral amine production owing to a unique enzyme property enabling both oxidative deamination of an amine involving conversion of enzyme-bound PLP to pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate (PMP) and reductive amination of a carbonyl compound accompanied by regeneration of the PLP form of enzyme (E-PLP) from the PMP form of enzyme (E-PMP), as shown in Fig. 1 (3–6). ω-TAs exhibit broad substrate specificity, a high turnover rate, stringent stereoselectivity, high enzyme stability, and no requirement for an external cofactor, all of which renders the enzyme suitable for industrial process development (2, 7).

Fig 1.

Reaction scheme of ω-TA-catalyzed transamination between an amino donor (shown in a box) and an amino acceptor (in a circle).

In the biocatalytic process design, complicated enzyme properties often limit efficient process operation (8, 9). Despite the enzyme properties of ω-TAs beneficial for industrial applications, severe product inhibition causing drastic reductions in the enzyme activity has been a major challenge to exploit the ω-TA reactions for industrial processes (3–5, 10–12). For example, ω-TA from Bacillus thuringiensis JS64 showed only 5% residual activity at 20 mM acetophenone in transamination between α-methylbenzylamine (α-MBA) and pyruvate (10). Therefore, several reaction engineering approaches to alleviate the inhibition by removing the ketone product using solvent extraction were developed (10, 12). The product inhibition has been regarded as a general property of ω-TAs, and there have been no reports on the discovery of an ω-TA lacking the product inhibition (3–6, 13). Yun et al. reported that product inhibition of ω-TA from Vibrio fluvialis JS17 by aliphatic ketones can be attenuated by directed evolution (14). However, it remains challenging to completely eliminate the product inhibition behaviors, although such an inhibition-free enzyme is in high demand for cost-effective processes.

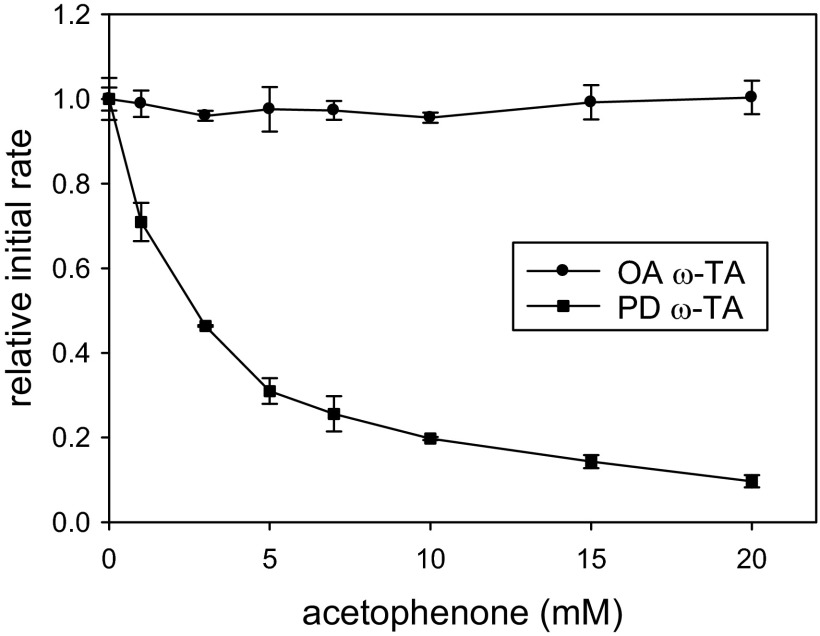

In the previous studies, we cloned, overexpressed, and purified (S)-selective ω-TAs from Ochrobactrum anthropi (15) and Paracoccus denitrificans PD1222 (16). Briefly, Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells carrying a pET28a(+) expression vector harboring the O. anthropi ω-TA or P. denitrificans ω-TA gene were cultivated in LB medium (typically 1 liter) and the His-tagged ω-TA was purified using a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) followed by a HiTrap desalting column (GE Healthcare) as described elsewhere (15, 16). When necessary, the purified enzyme solution was concentrated by an ultrafiltration kit (Ultracel-30) from Millipore Co. (Billerica, MA). Substrate specificities of the two ω-TAs were remarkably similar (15, 16), leading us to presume that both enzymes were prone to product inhibition. As previously observed with V. fluvialis ω-TA (13), P. denitrificans ω-TA exhibited strong product inhibition (only 10% residual activity at 20 mM acetophenone) (Fig. 2). Assuming that the product inhibition followed a hyperbolic decay (see detailed procedures in the supplemental material), the product inhibition constant (KPI) of acetophenone in the transamination between (S)-α-MBA and pyruvate (both 20 mM) was determined to be 2.4 ± 0.3 mM. However, to our surprise, O. anthropi ω-TA did not show such inhibition at all up to 20 mM acetophenone. These contrasting inhibition properties of the two ω-TAs were not affected by the choice of an amino acceptor (see entry 1 in Table S1 in the supplemental material, where 2-oxobutyrate was used instead of pyruvate). Based on the kinetic model we built previously to describe kinetic properties of B. thuringiensis and V. fluvialis ω-TAs (11, 17), the product inhibition results from strong binding of acetophenone to the active site of E-PMP that hinders an amino acceptor from binding to E-PMP. Consistent with this, acetophenone strongly inhibited P. denitrificans ω-TA even in the reaction between l-alanine and 2-oxobutyrate, in which acetophenone was not a cognate product (see entry 2 in Table S1 in the supplemental material). In contrast, O. anthropi ω-TA did not show such inhibition, suggesting that the lack of product inhibition observed with O. anthropi ω-TA results from a binding affinity of E-PMP toward acetophenone that is much lower than that toward pyruvate and 2-oxobutyrate.

Fig 2.

Product inhibition of O. anthropi (OA) and P. denitrificans (PD) ω-TAs by acetophenone in transamination between (S)-α-MBA and pyruvate.

We further examined whether O. anthropi ω-TA was also devoid of product inhibitions by other ketones, e.g., two arylaliphatic ketones (propiophenone and 1-indanone) and two aliphatic ketones (2-butanone and cyclopropyl methyl ketone). None of the reactions between chiral amines (α-ethylbenzylamine, 1-aminoindan, sec-butylamine, and cyclopropylethylamine) and pyruvate were inhibited by the ketone product (see entries 3 to 6 in Table S1 in the supplemental material), indicating that the lack of the product inhibition is a general property of O. anthropi ω-TA. In contrast, P. denitrificans ω-TA showed strong product inhibitions by all those ketones (i.e., KPI values ranging from 4.3 to 28.5 mM) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

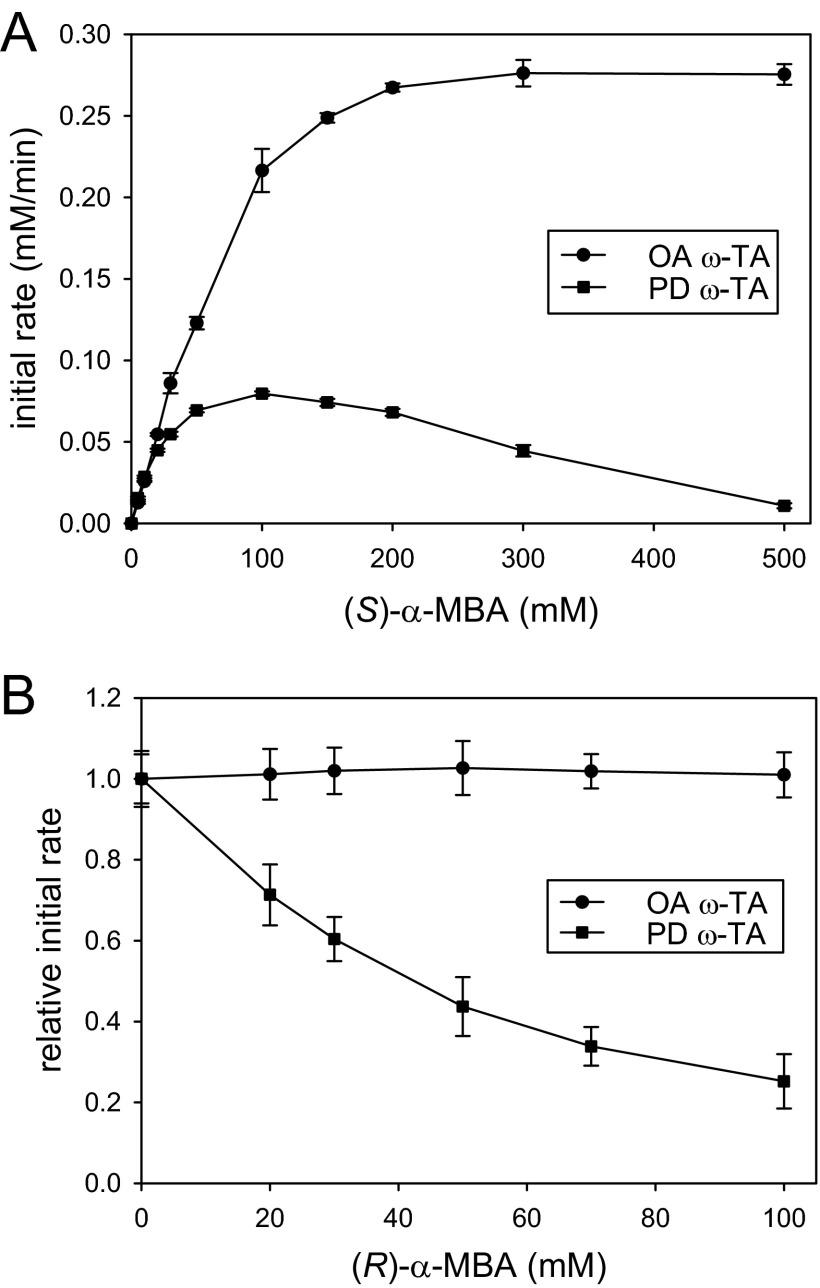

Besides the product inhibition, substrate inhibitions by both enantiomers of chiral amines, as previously observed with V. fluvialis ω-TA, render kinetic properties of ω-TAs much more complicated (11). Because O. anthropi and P. denitrificans ω-TAs displayed contrasting product inhibitions, we examined whether inhibition properties of the two ω-TAs were different toward amine substrates. Indeed, the ω-TAs showed completely different substrate inhibitions by α-MBA (Fig. 3). P. denitrificans ω-TA showed significant substrate inhibition by (S)-α-MBA (i.e., a reacting enantiomer) above 100 mM, whereas O. anthropi ω-TA was not inhibited at all up to 500 mM (Fig. 3A). Moreover, in contrast to strong inhibition of P. denitrificans ω-TA by (R)-α-MBA in the transamination between (S)-α-MBA and pyruvate (both 20 mM), O. anthropi ω-TA is devoid of such inhibition by the nonreacting enantiomer of α-MBA (Fig. 3B). The strong substrate inhibition of P. denitrificans ω-TA was also observed with achiral amine substrates, such as benzylamine (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Fig 3.

Substrate inhibitions of O. anthropi (OA) and P. denitrificans (PD) ω-TAs by α-MBA. (A) Enzyme inhibition at high concentrations of (S)-α-MBA in the reaction with pyruvate. Enzyme concentrations were 0.05 U/ml. (B) Enzyme inhibition by (R)-α-MBA in the reaction between (S)-α-MBA and pyruvate.

From the initial rate measurements shown in Fig. 3, we determined kinetic parameters of the two enzymes (Table 1). For the kinetic analysis, we used a pseudo-one-substrate model as previously described (18). In the case of P. denitrificans ω-TA, initial rate data obtained in the absence of the substrate inhibitions were used to determine the Michaelis constant (Km) and the maximum reaction rate (Vmax). Similarly to the product inhibitions, substrate inhibitions (KSI) were assumed to follow hyperbolic decay (see detailed procedures in the supplemental material). The Km(S)-α-MBA of P. denitrificans ω-TA (31 mM) was much lower than that of O. anthropi ω-TA (126 mM), indicating that the active site of O. anthropi ω-TA forms a relatively weak Michaelis complex between the E-PLP form and (S)-α-MBA. In the previous study, the Km values of four reactive arylalkylamines measured with V. fluvialis ω-TA were between 0.29 and 33 (11). Therefore, the Km(S)-α-MBA of O. anthropi ω-TA is unusually larger than typical Km values of reactive arylalkylamines. We previously proposed that substrate inhibitions by (S)- and (R)-enantiomers of chiral amines resulted from nonproductive binding to E-PMP and E-PLP, respectively (11). It is likely that such a low binding affinity of the E-PLP form of O. anthropi ω-TA toward (S)-α-MBA leads to negligible binding of (S)- and (R)-enantiomers of α-MBA to E-PMP and E-PLP, respectively, which may explain the lack of the substrate inhibitions of O. anthropi ω-TA. Similarly, the lack of product inhibition by acetophenone can be explained by the high Km(S)-α-MBA because the same active-site residues are involved in the Michaelis complex formation between E-PMP and acetophenone. Despite the weaker binding affinity toward (S)-α-MBA, catalytic turnover by O. anthropi ω-TA was found to be 4-fold faster than that by P. denitrificans ω-TA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of P. denitrificans and O. anthropi ω-TAsa

| Parameter | Value for each ω-TA |

|

|---|---|---|

| P. denitrificans | O. anthropi | |

| Vmax (mM/min/[U/ml])b | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 9.4 ± 2.7 |

| Km(S)-α-MBA (mM) | 31 ± 3 | 126 ± 33 |

| KSI(S)-α-MBA (mM) | 294 ± 13 | NAc |

| KSI(R)-α-MBA (mM) | 39 ± 6 | NA |

Kinetic parameters represent the apparent rate constants determined at a fixed concentration of pyruvate (20 mM).

Vmax represents a maximum reaction rate normalized by an enzyme concentration.

NA, not applicable. Enzyme inhibition was not observed.

The dual substrate inhibitions by both enantiomers of chiral amines are highly detrimental to kinetic resolution of racemic amines, in which use of high concentrations of racemic amine substrates is preferred (19–21). The lack of enzyme inhibition by amine substrates turned out to be a general property of O. anthropi ω-TA because none of the racemic amines tested (i.e., α-MBA, α-ethylbenzylamine, p-fluoro-α-MBA, 1-methyl-3-phenylpropylamine, and sec-butylamine) caused substrate inhibition (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). In contrast, P. denitrificans ω-TA showed strong substrate inhibitions by all these amines (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material).

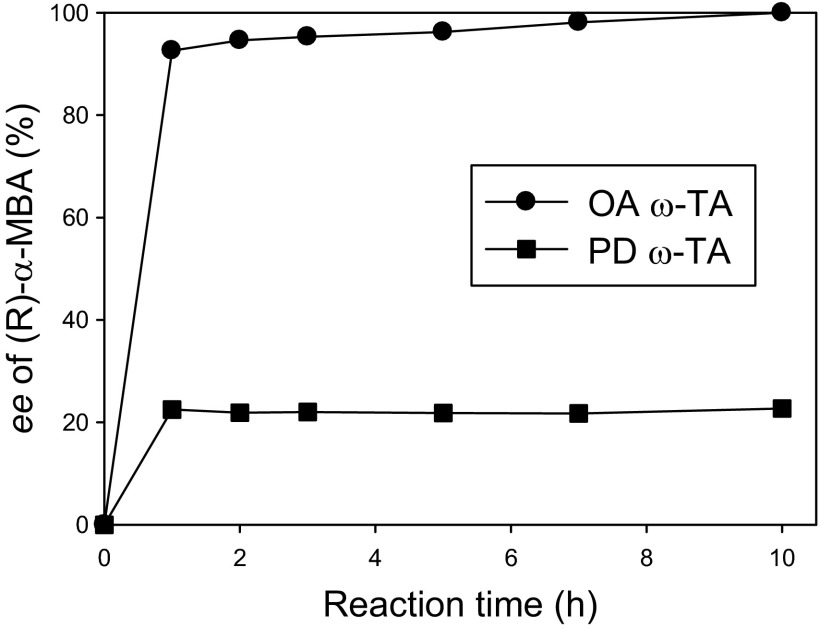

Compared with more than 20 ω-TAs identified so far (4), O. anthropi ω-TA displayed an unprecedented property devoid of enzyme inhibitions by ketone products as well as amine substrates. To assess how beneficial this unique property is to chiral amine production, we carried out kinetic resolution of 500 mM α-MBA at 300 mM pyruvate and 75 U/ml ω-TA (Fig. 4). When using O. anthropi ω-TA, enantiomeric excess (ee) of the resulting (R)-α-MBA reached 95.3% at 3 h and exceeded 99.9% (i.e., absolutely enantiopure) at 10 h, even without acetophenone removal. In contrast, kinetic resolution using P. denitrificans ω-TA did not show any substantial reaction progress after 1 h due to strong enzyme inhibition by produced acetophenone and led to only 22% ee at 10 h, a finding which illustrates why ketone product removal was indispensable to the previous studies using inhibition-susceptible ω-TAs (10, 12). This example clearly indicates that lack of the inhibition behaviors renders O. anthropi ω-TA ideal for kinetic resolution of chiral amines. In addition, we expect that the inhibition-free O. anthropi ω-TA may benefit asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines from prochiral ketones (22–24).

Fig 4.

Comparison of the kinetic resolutions of α-MBA using O. anthropi (OA) and P. denitrificans (PD) ω-TAs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Advanced Biomass R&D Center (ABC-2010-0029737) and the Basic Science Research Program (2010-0024448) through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

We are grateful for the technical assistance of Chao Li in the kinetic resolution using O. anthropi ω-TA.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 April 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03811-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hirotsu K, Goto M, Okamoto A, Miyahara I. 2005. Dual substrate recognition of aminotransferases. Chem. Rec. 5:160–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hwang BY, Cho BK, Yun H, Koteshwar K, Kim BG. 2005. Revisit of aminotransferase in the genomic era and its application to biocatalysis. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 37:47–55 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Höhne M, Bornscheuer UT. 2009. Biocatalytic routes to optically active amines. ChemCatChem 1:42–51 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koszelewski D, Tauber K, Faber K, Kroutil W. 2010. ω-Transaminases for the synthesis of non-racemic α-chiral primary amines. Trends Biotechnol. 28:324–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malik MS, Park ES, Shin JS. 2012. Features and technical applications of ω-transaminases. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 94:1163–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mathew S, Yun H. 2012. ω-Transaminases for the production of optically pure amines and unnatural amino acids. ACS Catal. 2:993–1001 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor PP, Pantaleone DP, Senkpeil RF, Fotheringham IG. 1998. Novel biosynthetic approaches to the production of unnatural amino acids using transaminases. Trends Biotechnol. 16:412–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liese A, Seelbach K, Wandrey C. (ed). 2006. Industrial biotransformation, 2nd ed Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wenda S, Illner S, Mell A, Kragl U. 2011. Industrial biotechnology—the future of green chemistry? Green Chem. 13:3007–3047 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shin JS, Kim BG. 1997. Kinetic resolution of α-methylbenzylamine with ω-transaminase screened from soil microorganisms: application of a biphasic system to overcome product inhibition. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 55:348–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shin JS, Kim BG. 2002. Substrate inhibition mode of ω-transaminase from Vibrio fluvialis JS17 is dependent on the chirality of substrate. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 77:832–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shin JS, Kim BG, Liese A, Wandrey C. 2001. Kinetic resolution of chiral amines with ω-transaminase using an enzyme-membrane reactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 73:179–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shin JS, Kim BG. 2001. Comparison of the ω-transaminases from different microorganisms and application to production of chiral amines. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:1782–1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yun H, Hwang BY, Lee JH, Kim BG. 2005. Use of enrichment culture for directed evolution of the Vibrio fluvialis JS17 ω-transaminase, which is resistant to product inhibition by aliphatic ketones. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4220–4224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park E-S, Kim M, Shin J-S. 2012. Molecular determinants for substrate selectivity of ω-transaminases. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 93:2425–2435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park E, Kim M, Shin JS. 2010. One-pot conversion of l-threonine into l-homoalanine: biocatalytic production of an unnatural amino acid from a natural one. Adv. Synth. Catal. 352:3391–3398 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shin JS, Kim BG. 1998. Kinetic modeling of ω-transamination for enzymatic kinetic resolution of α-methylbenzylamine. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 60:534–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park ES, Shin JS. 2011. Free energy analysis of ω-transaminase reactions to dissect how the enzyme controls the substrate selectivity. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 49:380–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Höhne M, Robins K, Bornscheuer UT. 2008. A protection strategy substantially enhances rate and enantioselectivity in ω-transaminase-catalyzed kinetic resolutions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 350:807–812 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hanson RL, Davis BL, Chen Y, Goldberg SL, Parker WL, Tully TP, Montana MA, Patel RN. 2008. Preparation of (R)-amines from racemic amines with an (S)-amine transaminase from Bacillus megaterium. Adv. Synth. Catal. 350:1367–1375 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Truppo MD, Turner NJ, Rozzell JD. 2009. Efficient kinetic resolution of racemic amines using a transaminase in combination with an amino acid oxidase. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2009:2127–2129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fuchs M, Koszelewski D, Tauber K, Kroutil W, Faber K. 2010. Chemoenzymatic asymmetric total synthesis of (S)-Rivastigmine using ω-transaminases. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 46:5500–5502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Höhne M, Kühl S, Robins K, Bornscheuer UT. 2008. Efficient asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines by combining transaminase and pyruvate decarboxylase. ChemBioChem 9:363–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koszelewski D, Lavandera I, Clay D, Guebitz GM, Rozzell D, Kroutil W. 2008. Formal asymmetric biocatalytic reductive amination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47:9337–9340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.