Abstract

The impact of the Borrelia burgdorferi surface-localized immunogenic lipoprotein BBA66 on vector and host infection was evaluated by inactivating the encoding gene, bba66, and characterizing the mutant phenotype throughout the natural mouse-tick-mouse cycle. The BBA66-deficient mutant isolate, BbΔA66, remained infectious in mice by needle inoculation of cultured organisms, but differences in spirochete burden and pathology in the tibiotarsal joint were observed relative to the parental wild-type (WT) strain. Ixodes scapularis larvae successfully acquired BbΔA66 following feeding on infected mice, and the organisms persisted in these ticks through the molt to nymphs. A series of tick transmission experiments (n = 7) demonstrated that the ability of BbΔA66-infected nymphs to infect laboratory mice was significantly impaired compared to that of mice fed upon by WT-infected ticks. trans-complementation of BbΔA66 with an intact copy of bba66 restored the WT infectious phenotype in mice via tick transmission. These results suggest a role for BBA66 in facilitating B. burgdorferi dissemination and transmission from the tick vector to the mammalian host as part of the disease process for Lyme borreliosis.

INTRODUCTION

Identifying gene products necessary for Borrelia burgdorferi, the tick-borne spirochete that causes Lyme borreliosis, to successfully navigate the complex environmental conditions encountered during the natural tick-to-mammalian host cycle has been of considerable recent interest. Work by several investigators has identified B. burgdorferi genes encoding outer membrane lipoproteins located on the 54-kb linear plasmid (lp54) that are functionally important in both the tick vector and mammalian hosts, e.g., ospA, ospB, cspA, dbpAB, and bba07 (1–6). A series of lp54 genes, designated bba64, -65, -66, and -73, has been of considerable interest because of properties suggestive of roles in tick-host infectivity. For example, these genes are among the most highly upregulated when B. burgdorferi is subjected to mammal- and tick-like conditions in vitro (7–12). Additionally, experimentally infected mice and Lyme disease patients develop humoral responses to many of the proteins encoded by these genes, indicating active synthesis and antigen processing by the host's immune system during infection (13–16). Accordingly, longitudinal studies of persistently infected mice found expression of the genes in B. burgdorferi localized to various tissues (13, 14, 17).

Consequently, investigating the functional role of these gene products in establishing B. burgdorferi infection has yielded some significant findings. Recently, we identified the outer surface lipoprotein BBA64 as a critical component in facilitating B. burgdorferi infection in mice strictly through inoculation by tick bite transmission (18, 19). Another membrane-associated protein, BBA66, has shown characteristics parallel to those of BBA64, suggesting a similar role in B. burgdorferi pathogenesis in ticks and/or in mammals. For example, BBA66 production by cultured B. burgdorferi was shown to be influenced by changes in pH and temperature, such as those that occur when an unfed tick consumes a blood meal on a host (8, 10, 16). BBA66 is surface localized and elicits an antibody response during infection of mice and in Lyme disease patients (13, 15, 16, 20). Additionally, bba66 is expressed during persistent mouse infection, suggestive of a maintenance function for B. burgdorferi in a reservoir host or as a needed component to colonize host tissues (14, 17). Studies by Anguita et al. suggested that bba66 may play a role in Lyme arthritis and carditis as assessed in the C3H/HeN mouse model (21), and Antonara et al. found evidence for BBA66 adhesion to murine heart tissue by phage display assay (22). Like other genes in this complex, notably bba64, bba66 is controlled by the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS global regulation pathway, which regulates a subset of genes both in the tick transition portion of the enzootic cycle and during mammalian infection (7, 13, 16, 23–26). B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains harbor BBA66 gene orthologs with a high level of conservation, and relapsing fever strains of Borrelia exhibit genes with lesser homology (13), but database searches do not reveal bba66 homologs in other procaryotes or eucaryotes.

Based on these biological properties, we hypothesized that BBA66 may fulfill an important function related to pathogen persistence and/or dissemination in tick and mammalian hosts. To test this hypothesis, we inactivated the bba66 gene and subjected the mutant isolate to the infectious stages of the natural tick-mouse enzootic cycle. We report that the mutant was attenuated in its ability to infect mice when delivered by tick bite, suggesting that BBA66 is a cofactor involved in borrelial tick maintenance pathways that mediate mammalian infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, ticks, and mice.

B. burgdorferi wild-type (WT) clonal infectious strain B31-A3 (BbWT) (27) was used as the parental strain for the generation of strain BbΔA66. B. burgdorferi cultures were grown in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly II (BSK-II) complete culture medium at 34°C in sealed tubes, with kanamycin and gentamicin used at 200 μg/ml and 50 μg/ml, respectively, when appropriate. B. burgdorferi isolates were maintained as low-passage (<2) frozen stocks in 30% glycerol at −80°C and maintained the full complement of plasmids, except for cp9. Male or female 6- to 8-week-old CD-1 mice were from a specific-pathogen-free colony maintained at the Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Fort Collins, CO) or purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Female C3H/HeJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME).

Infected Ixodes scapularis tick colonies were generated via xenodiagnosis by feeding uninfected I. scapularis larvae on CD-1 outbred mice infected via needle inoculation with 1 × 104 cells of BbWT, BbΔA66, or BbΔA66comp isolate as described previously (18).

Nymphal feeds were performed by anesthetizing mice by intraperitoneal injection with a ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) mixture. BbWT-, BbΔA66-, or BbΔA66comp-infected nymphs were placed dorsally on mice between the scapulae and allowed to feed to repletion (approximately 4 days). For the time course feeds, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and BbWT-infected nymphs were gently removed with fine-tip forceps at 33, 48, 57, and 72 h postinfestation. Mice were assayed for infection 21 days following the nymphal feeding by serology (immunoblotting against whole-cell B. burgdorferi lysates) and culture of ear biopsy specimens in BSK-II supplemented with antibiotics and fungizone as described previously (28). Experimental protocols involving mice were approved by the Division of Vector-borne Diseases and by the University of Pittsburgh Animal Care and Use Committees.

RNA isolation from ticks and qRT-PCR for bba66 expression.

RNA was isolated from unfed, replete, and actively feeding (33, 48, 57, and 72 h) BbWT-infected nymphs. Four nymphs were collected and pooled from each time point. Nymphs were homogenized with a glass Tenbroek grinder in 500 μl RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX) and stored at −80°C. Total RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) were performed as described previously (19) with bba66 TaqMan primers (14). Absolute expression levels of bba66 and flaB were determined according to known standard curves with transcript copies of bba66 measured as a ratio to copies of flaB. Data were calculated from 2 or 3 independent nymphal feedings for each time point (each technically replicated in triplicate).

Plasmid construction for insertional inactivation of bba66.

A 3,262-bp region encompassing bba66 and partial sequences of upstream and downstream genes (bba65 and bba68) was amplified by PCR from B. burgdorferi isolate B31 genomic DNA using primers bba65RT.R (TCAAGCAAAGAGAAATCATAGTA) and bba68RT.F (CTAAAAGCAATTGGTAAGGAACTG). The resulting product was cloned into pBAD-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). An internal region of bba66 (757 bp) was deleted by digestion with BglII and NheI, and the 1,243-bp kanamycin resistance cassette (29) was ligated into this site to yield pBADΔbba66::Kan. All plasmids were transformed into TOP10 Escherichia coli (Invitrogen), and clones were confirmed by PCR, restriction endonuclease digestion, and DNA sequencing. PCR primers used in this analysis were as follows: bba66 FL.1 (TTGAAAATCAAACCATTAATAC), bba66 FL.6 (TTACATTATACTAATGTATGCTTCAAG), 3′ Kan (CGAAAAACTCATCGAGCATCAA), and Gent.RT.R (CACTACGCGGCTGCTCAAACC).

Construction of plasmid for complementing the loss of bba66 expression.

The gene bba66 and its native promoter were amplified by PCR using primers proA66.1 (CTTGTCGCAAAAATAGAG) and bba66FL.6 and cloned into pCR8/GW/TOPO (Invitrogen). The shuttle vector pBSV2G (30) was converted into a Gateway destination vector using cassette RfB following the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). pCR8-bba66comp and pBSV2G-GDV-B were recombined using the Gateway system LP recombination reaction producing pBSV2G-bba66comp.

Electroporation of B. burgdorferi.

Plasmids were electroporated into either BbWT or BbΔA66 and plated into semisoft BSK media supplemented with antibiotics (31) with modification as described previously (32). Colonies appeared within 8 to 15 days and were cultivated in BSK-H Medium Complete, lot number 045K8412 or lot number 057K8413 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with antibiotics.

Mouse pathology studies.

Female C3H/HeJ mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were inoculated subcutaneously with 104 BbWT, BbΔA66, or BbΔA66comp cells. Tibiotarsal measurements were taken biweekly along with weekly blood collections. To determine the change in relative joint diameter in mice at each time point post-needle inoculation, age-matched mock-infected mice injected with BSK medium alone were measured alongside challenged mice. The change in joint diameter was determined by subtracting the measurements of mock-infected mice from those obtained with infected mice. After either 21 days or 35 days postinfection, mice were sacrificed, and heart, joint, and ear samples were collected for DNA isolation and/or outgrowth analysis.

DNA isolation and qPCR analysis.

DNA was isolated from heart, joint, and ear tissue as previously described (33). Tissues were incubated in a 0.1% collagenase A solution for 4 h at 37°C. An equal volume of 0.2 mg/ml of proteinase K was added and incubated at 55°C overnight, followed by a series of phenol-chloroform extractions and ethanol precipitations. qPCRs were performed in triplicate using iQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad) containing 0.5 μM concentrations of each β-actin primer (forward, AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC; reverse, CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT) and 1.0 μM each ospC primer (forward, TACGGATTCTAATGCGGTTTTAC; reverse, GTGATTATTTTCGGTATCCAAACCA). DNA was added to a final amount of 100 ng per reaction mixture. Reaction conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 50°C for 2 min, 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. Melting curves were generated by a cycle of 95°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 80 cycles of 50°C for 10 s with 0.5°C increments. Standard curves for ospC and β-actin were prepared using 10-fold serial dilutions of known quantities of B. burgdorferi or mouse DNA, respectively. Results are presented as copies of ospC per 106 copies of β-actin.

qPCR of B. burgdorferi in individual nymphs infected with BbWT or BbΔA66 was performed as previously described (19) with TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and flaB TaqMan probe and primers (14).

PCR of B. burgdorferi plasmids.

Plasmid contents for B. burgdorferi isolates were validated by performing multiplex PCR as described by Bunikis et al. (34).

IFAs, ELISAs, and antibodies.

Indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) were performed on feeding nymphs removed at 72 h postattachment dissected onto a silane-coated slide, air dried, and fixed in acetone for 10 min using chicken anti-BBA66 IgG (1:50) (Aves Laboratories, Tigard, OR) as described previously (19). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed as follows. Two hundred nanograms of recombinant BBA66 in 100 μl binding buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 8.6) was applied onto 96-well plates at 4°C overnight. After two washes in distilled water (dH2O), wells were blocked for 1 h at 25°C with blocking buffer (5% dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline plus 0.1% Tween 20 [PBS-T20]). Primary mouse sera, diluted by 2-fold serial dilution in blocking buffer, were incubated for 1 h at 25°C. After 3 washes with PBS-T20, 100 μl alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:20,000) in blocking buffer was incubated for 1 h at 25°C. Wells were washed with PBS-T20 (3×), and 100 μl 1-Step PNPP reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was incubated for 30 min at 25°C. Reactions were stopped with addition of 50 μl 2 N NaOH, and absorbance at 405 nm was measured. Primary antibodies for Western blot analysis included polyclonal mouse anti-B. burgdorferi sera collected from needle-inoculated mice and were used at a 1:1,000 dilution. Polyclonal antibody to OppAI (1:1,000) was provided by Linden Hu, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad software with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's multiple comparison test for assessment of changes in joint swelling and spirochete burden in tissues. When comparisons of 2 conditions were performed, a two-way t test was used. Statistical analysis of infected ticks per experimental mouse feeds was performed using one-way ANOVA for independent samples.

RESULTS

B. burgdorferi bba66 is expressed in feeding nymphal-stage ticks.

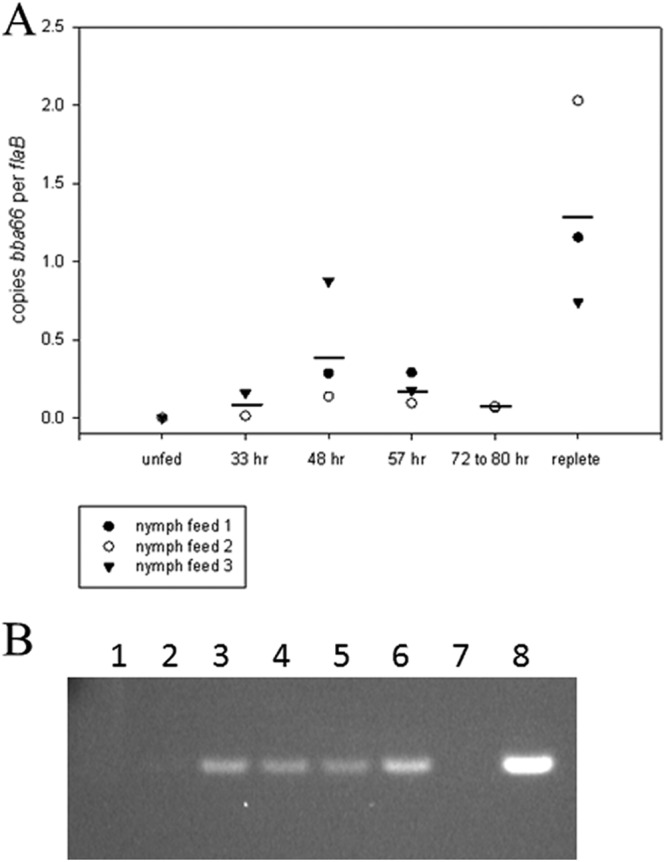

Total RNA was purified from B. burgdorferi wild-type (BbWT)-infected nymphal ticks detached from mice at times postattachment during feeding. Expression of bba66 in unfed ticks, at 33, 48, 57, and 72 h, and at repletion was determined by qRT-PCR and measured relative to absolute copies of flaB expression. bba66 expression was not detected in unfed nymphs but was detected beginning at 33 h postattachment, with continuous expression observed during the 3- to 4-day tick-feeding process. A spike in expression was seen in replete ticks collected approximately 4 to 20 h after dropoff (Fig. 1A). The bba66 amplicons from the qRT-PCRs were also visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

bba66 expression in feeding nymphal ticks by qRT-PCR. (A) RNA was isolated from pooled ticks from independent feedings (denoted by the open circles, filled circles, and triangles) at the designated times postattachment. Absolute bba66 transcript copies were measured as a ratio of copies per flaB. Horizontal bars represent the means of the samples. (B) Agarose gel image of bba66 amplicons following qRT-PCR. Lanes: 1, unfed nymphs; 2 to 5, nymphs at 33, 48, 57, and 72 to 80 h postinfestation, respectively; 6, replete nymphs; 7, no template DNA control; 8, BbWT genomic DNA positive control.

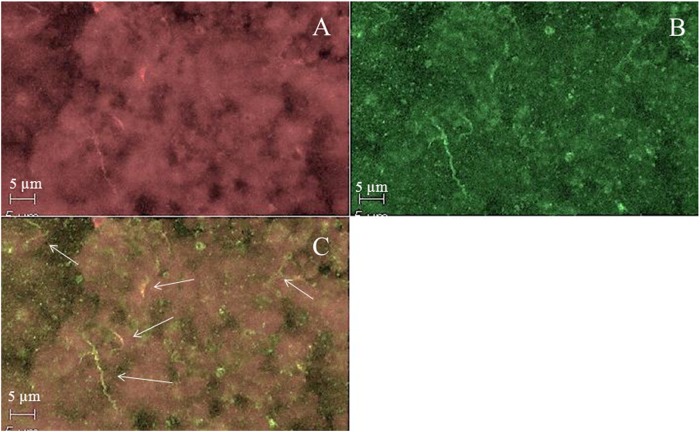

After demonstrating bba66 transcription during nymphal tick engorgement, we observed BBA66 production by immunofluorescence in a population of the organisms in midguts taken approximately 72 h postattachment (Fig. 2). These results show that bba66 is turned on and the gene product synthesized in the feeding tick.

Fig 2.

IFA of tick midgut approximately 72 h postattachment. (A) Field stained with anti-B. burgdorferi; (B) same field as in panel A, stained with anti-BBA66; (C) merged image of panels A and B. Arrows point to BBA66-stained organisms.

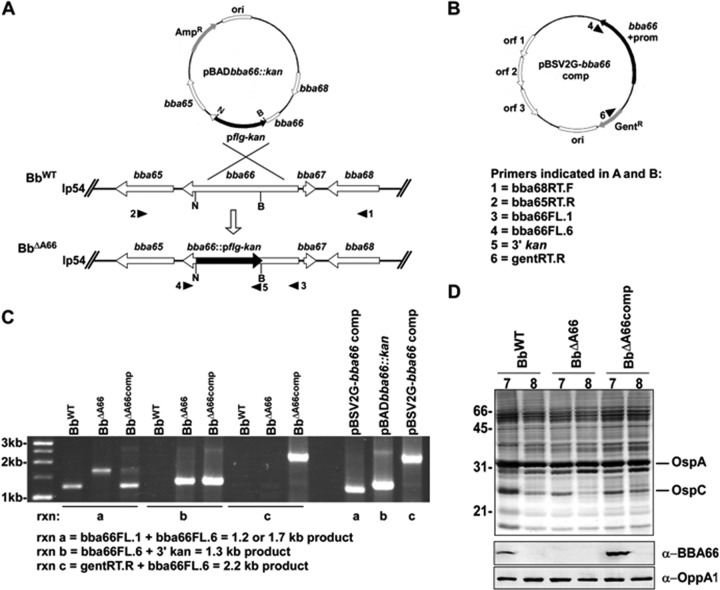

Generation of bba66 mutation in B. burgdorferi and complementation in trans.

A bba66 knockout mutant was generated by insertional mutagenesis to assess the putative role of BBA66 during the tick-mouse enzootic cycle. Following cloning of the WT bba66 gene plus upstream and downstream flanking regions into the E. coli plasmid vector pBAD-TOPO, the bba66 coding sequence was disrupted by insertion of a kanamycin resistance cassette under the control of the B. burgdorferi flagellin gene (flgB) promoter used as a selection marker (29). This construct, pBADbba66::Kan, was electroporated into B. burgdorferi B31-A3 and through homologous recombination resulted in the bba66-inactivated mutant isolate, BbΔA66 (Fig. 3A). The mutant was trans-complemented by electroporation of pBSV2G-bba66comp, which contained a WT copy of the bba66 gene, resulting in isolate BbΔA66comp (Fig. 3B). PCR analyses of the mutant and the complemented isolate showed proper insertion and orientation of the electroporated plasmids (Fig. 3C). Western blot analyses demonstrated the inactivation of BBA66 production in the mutant and restoration of BBA66 in the complemented isolate (Fig. 3D). Moreover, BBA66 production in BbΔA66comp responded to alterations in pH in a manner similar to what has been observed in WT infectious isolates (Fig. 3D). Finally, the production of BBA64 protein was not compromised in BbΔA66 (data not shown).

Fig 3.

Insertional inactivation of bba66 in infectious B. burgdorferi, complementation, and confirmation in vitro. (A) Schematic depicting the mutagenesis of BbWT bba66 by insertion of the pflg-kan cassette on lp54 by homologous recombination with pBADbba66::Kan. N and B indicate NheI and BglII restriction endonuclease sites utilized for insertion of the resistance marker. (B) Plasmid construct pBSV2G-bba66comp, used to complement the loss of bba66 in BbΔA66. The intact bba66 gene with its promoter (bba66 + prom) provides trans-complementation under gentamicin selection (GentR). Open reading frame 1 (orf 1), orf 2, orf 3, and origin of replication (ori) of pBSV2 are depicted. Numbers with arrowheads in panels A and B indicate primers (defined in panel B) and direction of amplification. (C) Agarose gel of PCR amplicons using the 3 primer sets indicated to verify kanamycin resistance marker insertion in BbΔA66. Reactions a, b, and c on the right depict control PCR with plasmid templates to verify correct amplicon sizes. Markers are indicated to the left in kilobases (kb). (D) SDS-PAGE separation and silver staining of equal amounts of cell protein lysates from BbWT, BbΔA66, and BbΔA66comp grown at pH 7 or pH 8. BBA66 is not visible by silver staining, but OspA and OspC are indicated by arrows for reference. Below the stained gel is an immunoblot of these cell lysates with anti-BBA66 demonstrating the loss of BBA66 in BbΔA66 and the pH regulation of bba66 in BbWT and BbΔA66comp. The immunoblot with anti-OppA1, which is not pH regulated in vitro, served as a loading control.

BbΔA66 is infectious by needle administration of cultured organisms.

C3H/HeJ mice were needle inoculated subcutaneously with 104 in vitro-cultivated BbWT, BbΔA66, Bb ΔA66comp cells and euthanized after 21 or 35 days postinfection (dpi). All mice became infected, (except for one mouse challenged with the BbΔA66comp isolate), as determined by culture of ear, heart, bladder, and joint tissues and by serological reactivity to Borrelia cell lysates (Table 1).

Table 1.

BBA66 is not required for infectivity by needle inoculation of C3H/HeJ mice

| Time postinfection and strain used | No. infected/no. inoculated |

No. positive by serology/no. inoculated | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | Bladder | Joint | Ear | Total | ||

| Day 21 | ||||||

| BbWT | NDb | 8/8 | ND | ND | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| BbΔbba66 | ND | 7/7 | ND | ND | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| BbΔbba66 comp | ND | 8/8 | ND | ND | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| Day 35 | ||||||

| BbWT | 8/8 | 7/8 | 5/8a | 4/8 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| BbΔbba66 | 7/8 | 8/8 | 6/8 | 3/8 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| BbΔbba66 comp | 7/8 | 7/8 | 6/8 | 3/8 | 7/8 | 7/8 |

Three cultures were contaminated.

ND, not determined.

Phenotypic analysis of BbΔA66 in the C3H/HeJ mouse model of Lyme arthritis after needle inoculation.

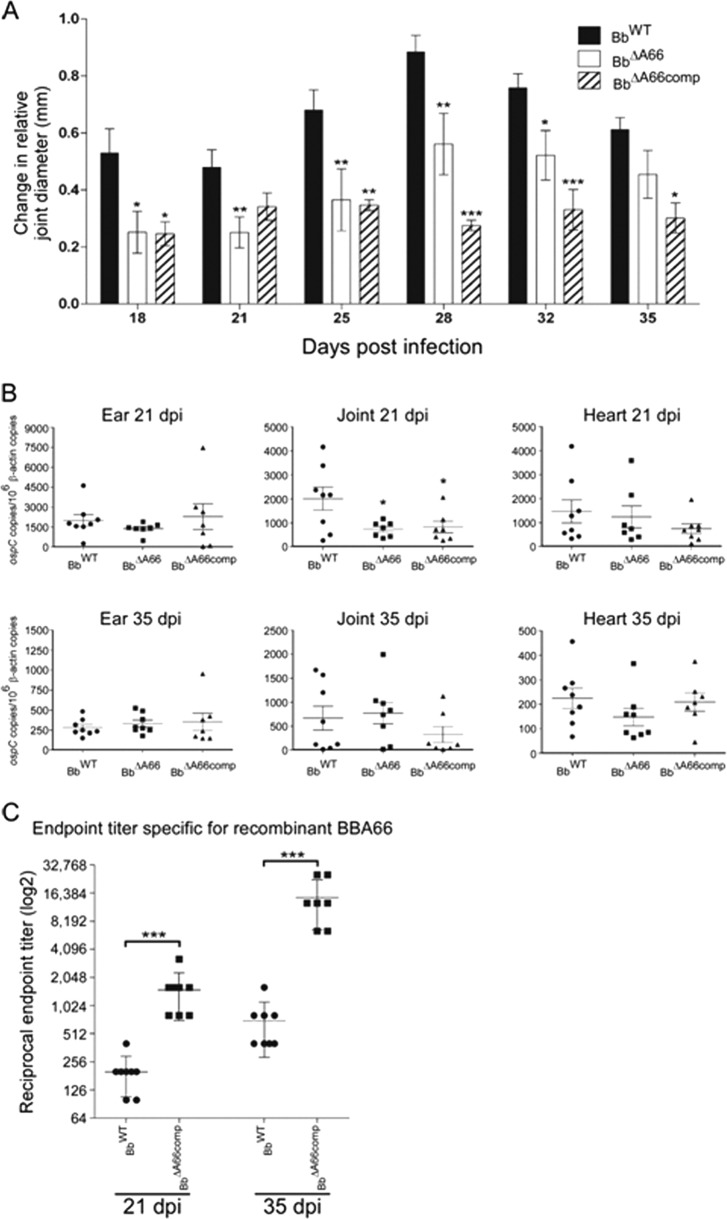

We measured the change in joint diameter of BbWT, BbΔA66, or BbΔA66comp needle-challenged C3H/HeJ mice during the course of infection as an indicator of joint inflammation common in the mouse model of Lyme arthritis. Measurements of both hind-limb joints were taken and compared to age-matched mock-infected mice as a baseline at 18, 21, 25, 28, 32, and 35 dpi (Fig. 4A). In mice inoculated with BbWT, joint diameter increased and peaked at 28 dpi (mean, 0.883 mm) and then began to decline. Likewise, mice infected with BbΔA66 demonstrated a similar peak in swelling at 28 dpi (mean, 0.561 mm), but the mean swelling was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) at 18, 21, 25, 28, and 32 dpi relative to mice infected with BbWT. Oddly, mice challenged with BbΔA66comp also presented with a significant reduction in mean joint diameter relative to BbWT-infected mice at all dpi monitored.

Fig 4.

Phenotypic analyses of C3H/HeJ mice needle inoculated with BbWT, BbΔA66, and BbΔA66comp. (A) Change in hind-limb joint diameter in millimeters (mm) was monitored 18, 21, 25, 28, 32, and 35 days postinfection. Reported changes are relative to age-matched, mock-challenged mice. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett's posttest was performed: *, P = 0.01 to 0.05; **, P = 0.001 to 0.01; ***, P = <0.001 relative to BbWT samples. (B) Joint tissues from mice needle inoculated with BbWT, BbΔA66, or BbΔA66comp were analyzed by qPCR to determine the relative differences in spirochete burden during infection. Borreliae were quantified by copies of ospC/106 copies of the mouse β-actin gene. *, P = 0.01 to 0.05. (C) ELISA results demonstrating immunoreactivity of infected mice to recombinant BBA66. Endpoint titers are presented as the reciprocal in log2. A two-way t test was performed to compare BbWT and BbΔA66comp at either 21 dpi or 35 dpi; ***, P = <0.001. Data points in panels B and C denote individual mice, with the mean denoted by a horizontal line and vertical lines with bars indicating the standard error of the mean.

To investigate the inability of BbΔA66comp to restore the WT phenotype in joint manifestations, qPCR was performed on joint tissue samples at 21 and 35 dpi to determine the spirochete load from mice needle inoculated with BbWT, BbΔA66, or BbΔA66comp. Analysis of the spirochete load in the joints of mice at 21 dpi found that mice challenged with BbWT had a mean of 2,010 copies ospC/106 copies of the mouse actin gene, yet mice infected with BbΔA66 or BbΔA66comp had a significant reduction (P < 0.05) in the number of spirochetes, with means of 739 and 822 copies ospC/106 copies of the mouse actin gene, respectively (Fig. 4B). This difference was not seen at 35 dpi and was likely due to the reduction in relative spirochete load as a function of time in the joints of mice infected with BbWT, while the BbΔA66 and BbΔA66comp numbers remained constant from 21 to 35 dpi. There was no difference in spirochete burdens between strains detected in other tissues tested, i.e., ears and hearts (Fig. 4B). The reduced burden of BbΔA66comp in joints may have been the reason for the observed decreased swelling by inflammation, and an experiment was performed to determine its cause.

The lack of restoration of WT joint swelling phenotype in BbΔA66comp-infected mice was not due to loss of the WT gene and subsequent reversion to mutant status, as determined by PCR analysis that showed WT bba66 was present in tissue reisolates of the infecting complemented organisms (data not shown). Therefore, we postulated that the multicopy nature of the complementing vector, pBSV2G (35), might have resulted in boosted production of BBA66 with a concomitant elevation in anti-BBA66 antibodies that could provide a mechanism for borrelial clearance. By Western blotting, we observed an increased amount of BBA66 produced in vitro in the BbΔA66comp relative to WT (Fig. 3D), and qRT-PCR of RNA from cultured isolates indicated 4-fold more bba66 transcript in BbΔA66comp relative to BbWT (data not shown). To determine if more BBA66 production in vivo with BbΔA66comp resulted in an enhanced antibody response, we determined the endpoint titers against recombinant BBA66 in sera from mice infected with BbWT and BbΔA66comp at 21 dpi and 35 dpi (Fig. 4C). Although the spirochete loads in the joint were 2.4-fold lower at 21 dpi in mice infected with BbΔA66comp than in mice infected with BbWT, we observed an 8-fold-higher anti-BBA66 specific mean titer in these mice relative to WT controls (1,600 relative to 200 reciprocal endpoint titer, P = 0.0004). This discrepancy in the anti-BBA66 specific mean endpoint titer grew to 16-fold at 35 dpi (12,800 relative to 800 reciprocal endpoint titer, P = 0.0003) and suggested that BBA66 was produced at considerably higher levels in BbΔA66comp-infected mice than in BbWT controls, leading to a more robust BBA66-specific antibody response. The higher-than-expected anti-BBA66 response could explain the clearing of the BbΔA66comp isolate from joint tissue, effectively hindering the rescue of the phenotype seen with the loss of bba66.

BbΔA66 is acquired by larvae following feeding on infected mice and persists transstadially to the nymphal stage.

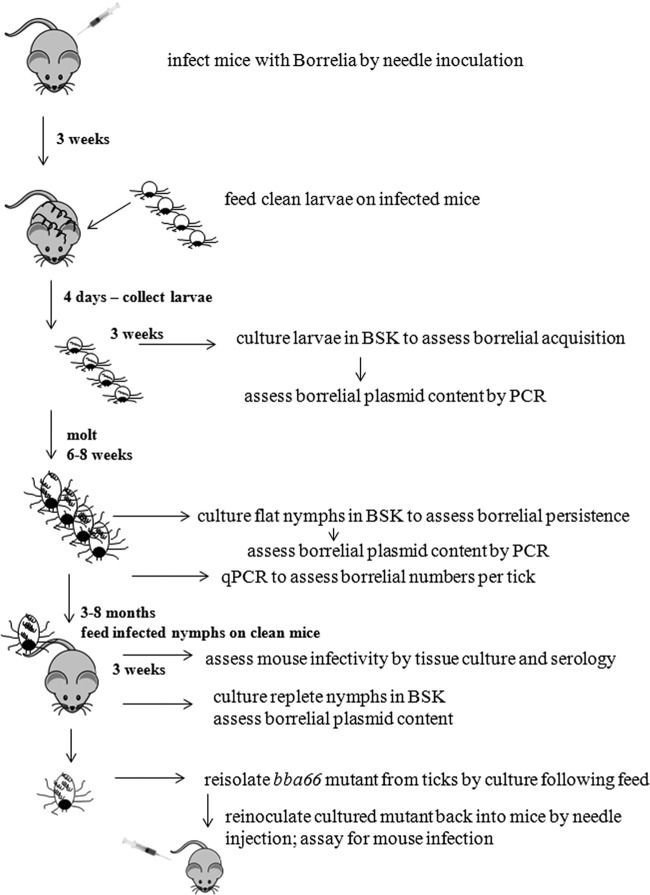

Steps in the experimental design to assess phenotypic differences between the BBA66 mutant and WT B. burgdorferi during the tick-mouse infectious cycle are shown in Fig. 5. Larval acquisition of BbΔA66was as efficient as BbWT acquisition based on several experiments and colony feeds during the course of this study. The acquisition rate by larvae for BbWT, BbΔA66, and BbΔA66comp were typically >80% (data not shown) as determined by culturing 20 to 30 individual replete larvae/cohort in BSK medium. Positive culture growth demonstrated that the mutant was viable following larval feeding, and PCR analysis showed that all plasmids were present in the WT and the BbΔA66 reisolates (data not shown). BbΔA66-infected unfed nymphs were cultured following the molt and prior to feeding. In each cohort, the mutant-infected nymphs were culture positive at the same percentage as following the larval acquisition, indicating that BbΔA66 was able to survive transstadially (data not shown).

Fig 5.

Flow chart of the experimental design to assess borrelial phenotypes through the mouse-tick-mouse natural cycle of infection.

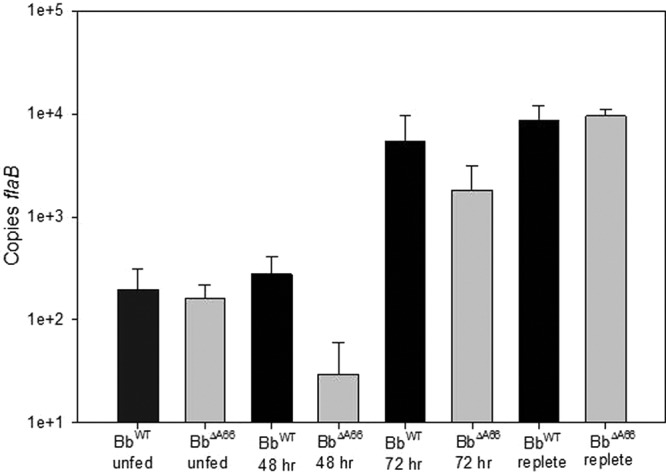

Quantitative PCR was performed on individual nymphs to determine the number of spirochetes present. The quantity of BbΔA66 was not significantly different from that of BbWT in the molted unfed nymphs (Fig. 6). Furthermore, PCR analysis revealed that no plasmids were lost in BbΔA66-infected unfed nymph culture reisolates (data not shown). These results demonstrated that BbΔA66was phenotypically identical to BbWT in the ability to be acquired by feeding larvae and in persistence through the molt to nymphs.

Fig 6.

qPCR enumerating BbWT and BbΔA66 isolates in individual ticks at times during mouse feeding. Bars indicate copies of flaB in unfed (flat) nymphs, in nymphs collected at 48 and 72 h postattachment, and in replete nymphs collected between 4 and 20 h after dropoff.

BbΔA66 is attenuated for mouse infection by nymphal tick transmission.

Following the larval molt, nymphs infected with the BbWT and BbΔA66 strains were fed on naive mice. Three weeks after tick detachment, the mice were checked for their susceptibility to the tick challenge infection by ear biopsy specimen culture and serology. The cumulative results of 7 individual experiments showed a statistically significant reduction in mouse infection following feeding by BbΔA66-infected ticks (Table 2). Collectively, the experiments revealed that 15/33 mice (45%) became infected after being fed upon by BbΔA66-infected nymphs, compared to 17/20 mice (85%) that became infected after BbWT-infected nymphal infestation (P value, 0.0082). All naive mice fed upon by nymphs colonized with BbΔA66comp (n = 5) became infected (Table 2, experiment number 5), with reisolates from mouse tissues harboring the WT bba66 (as detected by PCR), demonstrating restoration of mouse infectivity by tick transmission to WT levels. To validate that a reduction in transmission was the result of the bba66 mutation, the following parameters were examined in each of the 7 experiments: (i) fed mutant-infected nymphs were cultured from mice that remained uninfected to ascertain the presence of viable borreliae; (ii) the culture reisolates from these fed nymphs were assessed for their plasmid content to ensure that the isolates did not lose plasmids essential for mammalian infectivity (i.e., lp25, lp28-1, lp36, and cp26); and (iii) reisolates were assessed by PCR for the kanamycin resistance cassette insertion within bba66. In each instance, mice that remained uninfected following a BbΔA66-infected nymphal feed demonstrated fed ticks harboring viable mutant borreliae containing all the same plasmids as the parental strain. These results demonstrated the genetic stability of the mutant throughout each stage of the culture-mouse-tick-mouse infectious cycle.

Table 2.

Results of mouse challenge by tick transmission

| Experiment no. | B. burgdorferi strain infecting tick | No. of mice infected/no. of mice challenged | No. of nymphs placed/mouse | No. of replete infected nymphsa collected per: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected mouse | Uninfected mouse | ||||

| 1 | BbWT | 1/1 | 5 | 5 | |

| BbΔA66 | 0/4 | 5 | 1,1,3,3 | ||

| 2 | BbWT | 3/4 | 5,15b,15b,15b | 2,2,7 | 4 |

| BbΔA66 | 0/4 | 5,5,15b,15b | 3,3,3,1 | ||

| 3 | BbWT | 1/1 | 8 | 8 | |

| BbΔA66 | 0/3 | 10 | 8,5,6 | ||

| 4 | BbWT | 4/5 | 15b | 4,3,6,5 | 6 |

| BbΔA66 | 2/5 | 15b | 1,6 | 2,3,5 | |

| 5 | BbWT | 3/3 | 10 | 8,10,9 | |

| BbΔA66 | 5/7 | 10 | 10,10,6,8,8 | 6,7 | |

| BbΔA66comp | 5/5 | 10 | 6,6,6,3,7 | ||

| 6 | BbWT | 4/5 | 10 | 8,5,5,3 | 1 |

| BbΔA66 | 4/5 | 10 | 4,8,5,3 | 3 | |

| 7 | BbWT | 1/1 | 10 | 4 | |

| BbΔA66 | 4/5 | 10 | 3,5,4,4 | 1 | |

| Totalc | BbWT | 17/20 | |||

| BbΔA66 | 15/33 | ||||

Data also presented in Fig. 7.

Extra nymphs were placed on these mice for removal during the feed for time course PCR analyses.

P value = 0.0082 for BbWT versus BbΔA66.

Reisolated BbΔA66cultures from ticks that fed on mice refractory to infection were subsequently needle inoculated into individual naive mice (n = 3). All mice became infected, thus demonstrating that BbΔA66 retained its original phenotype of mouse infectivity by needle administration despite having traveled through the in vivo experimental cycle for many months. Together, these findings demonstrate that inactivation of bba66 contributes to an attenuation of mouse infectivity when the organisms are administered by tick bite.

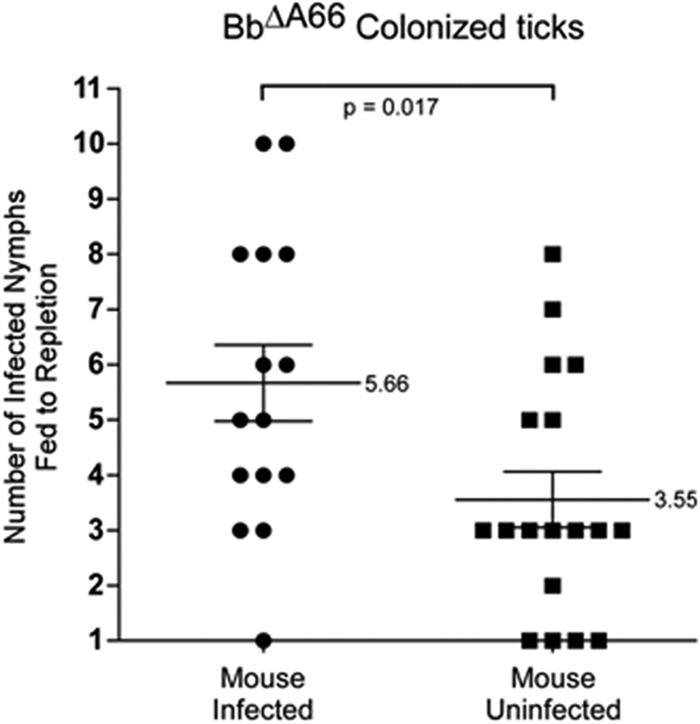

However, individual experiments showed variations in the percentage of mice infected by the mutant (Table 2). We assessed assorted experimental parameters that might have accounted for the observed variation including (i) mouse gender, (ii) mouse strain, (iii) age of nymphs, and (iv) number of ticks that fed to repletion. The one parameter that had a measurable effect on the experimental outcome was the number of BbΔA66-infected nymphs that fed to repletion. Statistical evaluation of the number of replete BbΔA66-infected nymphs collected from each mouse showed a significant difference between the number of nymphs that fed to completion and whether or not the mouse became infected (Fig. 7). The average number of infected nymphs that fed per infected mouse was 5.6. The average number of infected nymphs that fed per uninfected mouse was 3.6; a difference of 2 nymphs/mouse (P value = 0.017). The data indicated that mice fed upon by BbΔA66-infected nymphs had a better chance to become infected if 4 or more ticks completed the feeding process.

Fig 7.

Number of BbΔA66-infected ticks feeding to repletion as a correlation to mouse infectivity. Solid circles represent individual mice that became infected following feeding by BbΔA66-infected ticks; solid squares represent individual mice that did not become infected following feeding by BbΔA66-infected ticks. The mean value for each sample set is shown by the horizontal lines with the standard error of the mean denoted by the vertical lines. P value (0.017) determined by one-way ANOVA.

BbΔA66 replicates normally in ticks.

We evaluated whether the attenuation of mammalian infectivity was due to a defect in the mutant's ability to replicate normally within the tick during feeding. Borreliae were enumerated by qPCR in BbWT- and BbΔA66-infected nymphs taken throughout the 4-day engorgement period. The data demonstrated no significant differences in spirochete numbers between the two isolates measured through the feeding process (all P values were <0.05) (Fig. 6). This result indicates that BbΔA66 replicated normally and that attenuation of mouse infectivity was not due to a reduced density of organisms necessary for infection within the tick. Additionally, BbΔA66 growth curves were no different from those of BbWT when cultivated in BSK media (data not shown).

Quantification of BbΔA66 in infected mouse tissues following tick challenge.

The spirochete burden was measured by qPCR from tissues of necropsied mice that became infected by BbΔA66 and compared to BbWT-infected tissues. Ears, spleens, heart, and bladder tissues were assessed 6 to 8 weeks following tick feeding. Although the mean BbΔA66 density in tissues was lower in ear, bladder, and spleen tissues than the density in BbWT-infected tissues, there was not a statistically significant difference (data not shown). Therefore, BBA66-deficient organisms did not appreciably affect spirochete dissemination or replication in these tissues.

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms by which B. burgdorferi navigates its way from reservoir hosts to vector ticks and back again, incidentally infecting humans in this cycle, have been a subject of keen interest. The transmission of B. burgdorferi from vector ticks to humans signifies the first stage in Lyme disease causation. Defining the borrelial gene products instrumental in this process identifies potential targets for disruption of the cycle necessary for maintenance of the Lyme borreliosis agent in nature. In this study, we showed that bba66 was expressed in the nymphal tick stage during consumption of the host blood meal and, correspondingly, that the BBA66 protein was produced by spirochetes in the midgut. The upregulation of bba66 at this critical juncture of the enzootic transmission cycle suggested that BBA66 functions to prepare B. burgdorferi for transmission from vector to host and/or other host-pathogen interactions.

Following construction of a BBA66-deficient isolate, we began by assessing the ability of the mutant to infect mice by needle inoculation of cultured organisms. BbΔA66 proved infectious via this route of introduction, as has been demonstrated by other investigators using a triple deletion mutant lacking bba64, bba65, and bba66 (36). The one pathological phenotypic change in C3H/HeJ mice infected with BbΔA66 relative to mice infected with BbWT was a reduction in joint swelling at 21 dpi, a sign of reduced inflammation, suggesting that BBA66 is involved in joint inflammation and colonization in the mouse model of arthritis. Unfortunately, we were unable to restore the WT joint phenotype by complementation of the loss of bba66. We attributed this to the abnormally high BBA66 antibody titers that were generated in mice infected with BbΔA66comp. This result suggested that the reduced joint inflammation in BbΔA66comp-infected mice was a function of decreased spirochete numbers in the joint due to clearance by elevated anti-BBA66 antibodies, but apparently the elevated anti-BBA66 had little effect on spirochete numbers in other tissues assayed (Fig. 4B). One interpretation is that BBA66 may be more highly produced or more accessible on the cell surface in joint tissue or that organisms in joints may be more exposed to antibody attack relative to other tissues, thereby rendering spirochetes in the joint more susceptible to clearance. The evidence that BBA66 is involved in joint tissue colonization and that high levels of anti-BBA66 antibodies may help eliminate B. burgdorferi is a concept that warrants further investigation.

We subjected the BBA66-deficient mutant to the conditions of the natural mammalian host-vector cycle. Inactivation of bba66 did not prove detrimental for B. burgdorferi's ability to (i) be acquired by clean larvae after feeding on infected mice and (ii) persist transstadially from larva to nymph. However, the bba66 mutant was impaired in its ability for infecting mice when introduced by nymphal tick bite.

We observed variability in the tick transmission results, as the first 4 experiments demonstrated a pronounced phenotypic effect by the mutant whereas the subsequent 3 experiments showed no differences from WT controls. We addressed this concern by analyzing several experimental variables that could possibly affect the outcomes of tick feeding challenges. We determined that the strain and gender of host mice and age of feeding nymphs were nonfactors. The one parameter that appeared to affect transmission was the number of ticks allowed to infest mice for the challenge. Although a single WT-infected tick can infect a host, our lab routinely uses 5 to 10 ticks per mouse because it is uncommon to recover all ticks after the 4-day feed due to animal grooming or failure of individual ticks to attach. Moreover, not every nymph in a cohort is infected, as colony infectivity rates are not 100%. Therefore, we use multiple ticks in a feed to ensure recovery and documentation of at least one infected tick per animal to validate the final infection status of the mouse. In two experiments, we infested some mice with 15 nymphs for reasons of detaching the extra ticks prior to repletion for use in PCR analyses, leaving 8 to 10 ticks to remain feeding. The interruption of tick feeding by removal of a few from the animal did not have a discernible effect on the eventual host infectivity status. Although it cannot be proven with certainty, it does not seem likely that removal of some ticks would affect the feeding and borrelial transmission from the other ticks that fed to repletion.

We found a statistically significant difference between the numbers of BbΔA66-infected nymphs that completed the feed per infected mouse versus uninfected mouse. These data suggest that there was a greater probability of mice becoming infected with BbΔA66 when more ticks fed to completion and may explain the results of the latter trials whereby mutant-infected mice usually had 4 or more ticks collected at the end of feeding. Bestor et al. observed a similar phenomenon in experiments whereby an isolate lacking the genes bba01-07 was infectious by tick bite when 20 ticks per mouse were used, but not when the infestation was reduced to 3 ticks per mouse (37, 38).

By this data analysis, we propose a model whereby BBA66 functions via a (currently undefined) mechanism to prepare B. burgdorferi for transport from tick to host during the nymph feeding period. Inactivation of bba66 retards the normal dissemination of organisms in the tick whereby a suboptimal number of cells are eventually transmitted to the host, i.e., at a level below the 50% infectious dose (ID50). The few BBA66-deficient borreliae that are distributed from the tick and deposited into the host skin are subsequently destroyed by the host's innate immune response, resulting in clearance of infection as measured 2 to 3 weeks following tick challenge. However, when several mutant-infected ticks are allowed to complete the feeding process, the result may be a collective inoculum of BbΔA66 that exceeds the ID50, subsequently causing a breakthrough host infection. Because it has been clearly established that a single infected tick feeding on a host can cause Lyme borreliosis, it may be prudent to conduct future experiments allowing a feeding of 1 to 3 BbΔA66 (and other mutant)-infected ticks/mouse when studying the mechanisms involved in pathogen transmission.

Collectively, our findings support two general hypotheses: (i) BBA66 plays a role in joint pathology; and (ii) BBA66 functions within the tick for borrelial dissemination, affecting transmission to and infectivity of the host. Moreover, the results reinforce an important point made in several studies, that tick-borne B. burgdorferi possesses biological properties distinct from those of in vitro-grown organisms, as evidenced by the infectious phenotype of BbΔA66 when needle inoculated, in contrast to what is seen with inoculation by tick bite.

Recent research investigating borrelia-vector interactions have focused on inactivation of global regulators, individual genes, and replicons to advance our understanding of B. burgdorferi tick colonization and persistence and vector transmission mechanisms (1, 4, 7, 18, 37–54). The loss of BBA66 activity did not completely abolish the ability of B. burgdorferi to invade the host by tick bite (at least when more than 4 ticks/mouse fed to repletion), but mouse infectivity was significantly impaired. This phenotype was observed solely by tick bite inoculation and not by needle inoculation of culture-grown organisms; therefore, we conclude that BBA66 functions in the tick vector to facilitate host infection in the natural cycle of Lyme borreliosis. Undoubtedly, an intricate mechanism exists that incorporates elements of the spirochete, vector, and mammal for successful passage from one host to another to complete the infectious cycle. BBA66 is another component of this pathway and adds to our current knowledge of the biological processes involved in vector-borne diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the Animal Resource Branch at DVBD, John Liddell, Sarah Maes, Andrea Peterson, and Verna O'Brien for their assistance in animal care and maintenance, and Jennifer Damicis for laboratory support. We thank Jessica Hughes for technical assistance in creation of the bba66 mutant and complemented isolates while completing her dissertation at the University of Pittsburgh.

This research was supported in part by CDC cooperative agreement CI000181 and Grant-In-Aid 0855453D from the American Heart Association awarded to J.A.C.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Yang XF, Pal U, Alani SM, Fikrig E, Norgard MV. 2004. Essential role for OspA/B in the life cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete. J. Exp. Med. 199:641–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neelakanta G, Li X, Pal U, Liu X, Beck DS, DePonte K, Fish D, Kantor FS, Fikrig E. 2007. Outer surface protein B is critical for Borrelia burgdorferi adherence and survival within Ixodes ticks. PLoS Pathog. 3:e33. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. von Lackum K, Miller JC, Bykowski T, Riley SP, Woodman ME, Brade V, Kraiczy P, Stevenson B, Wallich R. 2005. Borrelia burgdorferi regulates expression of complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 1 during the mammal-tick infection cycle. Infect. Immun. 73:7398–7405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xu H, He M, He JJ, Yang XF. 2010. Role of the surface lipoprotein BBA07 in the enzootic cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 78:2910–2918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weening EH, Parveen N, Trzeciakowski JP, Leong JM, Hook M, Skare JT. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi lacking DbpBA exhibits an early survival defect during experimental infection. Infect. Immun. 76:5694–5705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shi Y, Xu Q, McShan K, Liang FT. 2008. Both decorin-binding proteins A and B are critical for the overall virulence of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 76:1239–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caimano MJ, Iyer R, Eggers CH, Gonzalez C, Morton EA, Gilbert MA, Schwartz I, Radolf JD. 2007. Analysis of the RpoS regulon in Borrelia burgdorferi in response to mammalian host signals provides insight into RpoS function during the enzootic cycle. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1193–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Revel AT, Talaat AM, Norgard MV. 2002. DNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:1562–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tokarz R, Anderton JM, Katona LI, Benach JL. 2004. Combined effects of blood and temperature shift on Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression as determined by whole genome DNA array. Infect. Immun. 72:5419–5432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ojaimi C, Brooks C, Casjens S, Rosa P, Elias A, Barbour A, Jasinskas A, Benach J, Katona L, Radolf J, Caimano M, Skare J, Swingle K, Akins D, Schwartz I. 2003. Profiling of temperature-induced changes in Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression by using whole genome arrays. Infect. Immun. 71:1689–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brooks CS, Hefty PS, Jolliff SE, Akins DR. 2003. Global analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi genes regulated by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 71:3371–3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carroll JA, Cordova RM, Garon CF. 2000. Identification of 11 pH-regulated genes in Borrelia burgdorferi localizing to linear plasmids. Infect. Immun. 68:6677–6684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hughes JL, Nolder CL, Nowalk AJ, Clifton DR, Howison RR, Schmit VL, Gilmore RD, Jr, Carroll JA. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi surface-localized proteins expressed during persistent murine infection are conserved among diverse Borrelia spp. Infect. Immun. 76:2498–2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gilmore RD, Jr, Howison RR, Schmit VL, Nowalk AJ, Clifton DR, Nolder C, Hughes JL, Carroll JA. 2007. Temporal expression analysis of the Borrelia burgdorferi paralogous gene family 54 genes BBA64, BBA65, and BBA66 during persistent infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 75:2753–2764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nowalk AJ, Gilmore RD, Jr, Carroll JA. 2006. Serologic proteome analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi membrane-associated proteins. Infect. Immun. 74:3864–3873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clifton DR, Nolder CL, Hughes JL, Nowalk AJ, Carroll JA. 2006. Regulation and expression of bba66 encoding an immunogenic infection-associated lipoprotein in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 61:243–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gilmore RD, Jr, Howison RR, Schmit VL, Carroll JA. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi expression of the bba64, bba65, bba66, and bba73 genes in tissues during persistent infection in mice. Microb. Pathog. 45:355–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilmore RD, Jr, Howison RR, Dietrich G, Patton TG, Clifton DR, Carroll JA. 2010. The bba64 gene of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent, is critical for mammalian infection via tick bite transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:7515–7520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patton TG, Dietrich G, Dolan MC, Piesman J, Carroll JA, Gilmore RD., Jr 2011. Functional analysis of the Borrelia burgdorferi bba64 gene product in murine infection via tick infestation. PLoS One 6:e19536. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brooks CS, Vuppala SR, Jett AM, Akins DR. 2006. Identification of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface proteins. Infect. Immun. 74:296–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anguita J, Samanta S, Revilla B, Suk K, Das S, Barthold SW, Fikrig E. 2000. Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression in vivo and spirochete pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 68:1222–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Antonara S, Chafel RM, LaFrance M, Coburn J. 2007. Borrelia burgdorferi adhesins identified using in vivo phage display. Mol. Microbiol. 66:262–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boardman BK, He M, Ouyang Z, Xu H, Pang X, Yang XF. 2008. Essential role of the response regulator Rrp2 in the infectious cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 76:3844–3853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dunham-Ems SM, Caimano MJ, Eggers CH, Radolf JD. 2012. Borrelia burgdorferi requires the alternative sigma factor RpoS for dissemination within the vector during tick-to-mammal transmission. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002532. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fisher MA, Grimm D, Henion AK, Elias AF, Stewart PE, Rosa PA, Gherardini FC. 2005. Borrelia burgdorferi sigma54 is required for mammalian infection and vector transmission but not for tick colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:5162–5167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ouyang Z, Blevins JS, Norgard MV. 2008. Transcriptional interplay among the regulators Rrp2, RpoN and RpoS in Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology 154:2641–2658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Elias AF, Stewart PE, Grimm D, Caimano MJ, Eggers CH, Tilly K, Bono JL, Akins DR, Radolf JD, Schwan TG, Rosa P. 2002. Clonal polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 MI: implications for mutagenesis in an infectious strain background. Infect. Immun. 70:2139–2150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sinsky RJ, Piesman J. 1989. Ear punch biopsy method for detection and isolation of Borrelia burgdorferi from rodents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1723–1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bono JL, Elias AF, Kupko JJ, III, Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa P. 2000. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 182:2445–2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elias AF, Bono JL, Kupko JJ, III, Stewart PE, Krum JG, Rosa PA. 2003. New antibiotic resistance cassettes suitable for genetic studies in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 6:29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carroll JA, Stewart PE, Rosa P, Elias AF, Garon CF. 2003. An enhanced GFP reporter system to monitor gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology 149:1819–1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosa P, Samuels DS, Hogan D, Stevenson B, Casjens S, Tilly K. 1996. Directed insertion of a selectable marker into a circular plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 178:5946–5953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang L, Weis JH, Eichwald E, Kolbert CP, Persing DH, Weis JJ. 1994. Heritable susceptibility to severe Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis is dominant and is associated with persistence of large numbers of spirochetes in tissues. Infect. Immun. 62:492–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bunikis I, Kutschan-Bunikis S, Bonde M, Bergstrom S. 2011. Multiplex PCR as a tool for validating plasmid content of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Microbiol. Methods 86:243–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tilly K, Krum JG, Bestor A, Jewett MW, Grimm D, Bueschel D, Byram R, Dorward D, Vanraden MJ, Stewart P, Rosa P. 2006. Borrelia burgdorferi OspC protein required exclusively in a crucial early stage of mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 74:3554–3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maruskova M, Seshu J. 2008. Deletion of BBA64, BBA65, and BBA66 loci does not alter the infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine model of Lyme disease. Infect. Immun. 76:5274–5284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bestor A, Stewart PE, Jewett MW, Sarkar A, Tilly K, Rosa PA. 2010. Use of the Cre-lox recombination system to investigate the lp54 gene requirement in the infectious cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 78:2397–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bestor A, Rego RO, Tilly K, Rosa PA. 2012. Competitive advantage of Borrelia burgdorferi with outer surface protein BBA03 during tick-mediated infection of the mammalian host. Infect. Immun. 80:3501–3511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jewett MW, Lawrence KA, Bestor A, Byram R, Gherardini F, Rosa PA. 2009. GuaA and GuaB are essential for Borrelia burgdorferi survival in the tick-mouse infection cycle. J. Bacteriol. 191:6231–6241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Revel AT, Blevins JS, Almazan C, Neil L, Kocan KM, de la Fuente J, Hagman KE, Norgard MV. 2005. bptA (bbe16) is essential for the persistence of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, in its natural tick vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:6972–6977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li X, Pal U, Ramamoorthi N, Liu X, Desrosiers DC, Eggers CH, Anderson JF, Radolf JD, Fikrig E. 2007. The Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi requires BB0690, a Dps homologue, to persist within ticks. Mol. Microbiol. 63:694–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Banik S, Terekhova D, Iyer R, Pappas CJ, Caimano MJ, Radolf JD, Schwartz I. 2011. BB0844, an RpoS-regulated protein, is dispensable for Borrelia burgdorferi infectivity and maintenance in the mouse-tick infectious cycle. Infect. Immun. 79:1208–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xu H, He M, Pang X, Xu ZC, Piesman J, Yang XF. 2010. Characterization of the highly regulated antigen BBA05 in the enzootic cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 78:100–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Promnares K, Kumar M, Shroder DY, Zhang X, Anderson JF, Pal U. 2009. Borrelia burgdorferi small lipoprotein Lp6.6 is a member of multiple protein complexes in the outer membrane and facilitates pathogen transmission from ticks to mice. Mol. Microbiol. 74:112–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kumar M, Yang X, Coleman AS, Pal U. 2010. BBA52 facilitates Borrelia burgdorferi transmission from feeding ticks to murine hosts. J. Infect. Dis. 201:1084–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang L, Zhang Y, Adusumilli S, Liu L, Narasimhan S, Dai J, Zhao YO, Fikrig E. 2011. Molecular interactions that enable movement of the Lyme disease agent from the tick gut into the hemolymph. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002079. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. He M, Ouyang Z, Troxell B, Xu H, Moh A, Piesman J, Norgard MV, Gomelsky M, Yang XF. 2011. Cyclic di-GMP is essential for the survival of the Lyme disease spirochete in ticks. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002133. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Caimano MJ, Kenedy MR, Kairu T, Desrosiers DC, Harman M, Dunham-Ems S, Akins DR, Pal U, Radolf JD. 2011. The hybrid histidine kinase Hk1 is part of a two-component system that is essential for survival of Borrelia burgdorferi in feeding Ixodes scapularis ticks. Infect. Immun. 79:3117–3130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kostick JL, Szkotnicki LT, Rogers EA, Bocci P, Raffaelli N, Marconi RT. 2011. The diguanylate cyclase, Rrp1, regulates critical steps in the enzootic cycle of the Lyme disease spirochetes. Mol. Microbiol. 81:219–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blevins JS, Revel AT, Caimano MJ, Yang XF, Richardson JA, Hagman KE, Norgard MV. 2004. The luxS gene is not required for Borrelia burgdorferi tick colonization, transmission to a mammalian host, or induction of disease. Infect. Immun. 72:4864–4867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sze CW, Zhang K, Kariu T, Pal U, Li C. 2012. Borrelia burgdorferi needs chemotaxis to establish infection in mammals and to accomplish its enzootic cycle. Infect. Immun. 80:2485–2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pappas CJ, Iyer R, Petzke MM, Caimano MJ, Radolf JD, Schwartz I. 2011. Borrelia burgdorferi requires glycerol for maximum fitness during the tick phase of the enzootic cycle. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002102. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pal U, Dai J, Li X, Neelakanta G, Luo P, Kumar M, Wang P, Yang X, Anderson JF, Fikrig E. 2008. A differential role for BB0365 in the persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in mice and ticks. J. Infect. Dis. 197:148–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ristow LC, Miller HE, Padmore LJ, Chettri R, Salzman N, Caimano MJ, Rosa PA, Coburn J. 2012. The beta(3)-integrin ligand of Borrelia burgdorferi is critical for infection of mice but not ticks. Mol. Microbiol. 85:1105–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]