Abstract

The first case of a spinal epidural abscess caused by Roseomonas mucosa following instrumented posterior lumbar fusion is presented. Although rare, because of its highly resistant profile, Roseomonas species should be included in the differential diagnosis of epidural abscesses in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent hosts.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old woman was admitted to the Emergency Department of the University Hospital in Crete, Greece, with complaints of purulent drainage, mild pain, and redness at the site of incision. The patient had been operated on 15 days previously due to spinal stenosis. The type of surgery performed was decompressive lumbar laminectomy followed by instrumented posterior spinal fusion.

Physical examination revealed a large, deep-wound dehiscence with exudates, erythema, pain, induration, edema, and cellulitis.

The general condition of the patient was good. She was feverless, and results of the laboratory exams were the following: a white blood cell (WBC) count of 6,000/mm3, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 97 mm/h, and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 4.82 mg/dl (normal range, 0.08 to 08 mg/dl). The patient underwent deep surgical debridement and was placed on empirical intravenous (i.v.) vancomycin and oral rifampin for a total of 24 days.

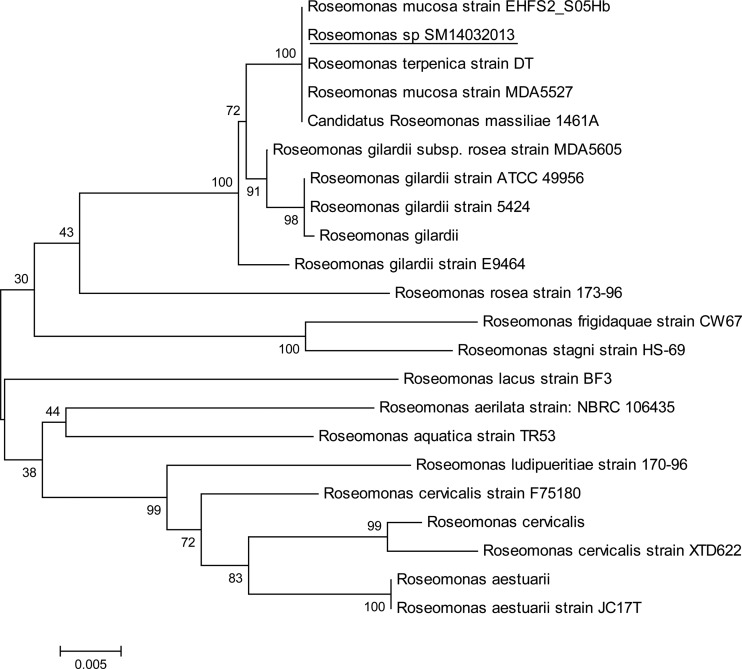

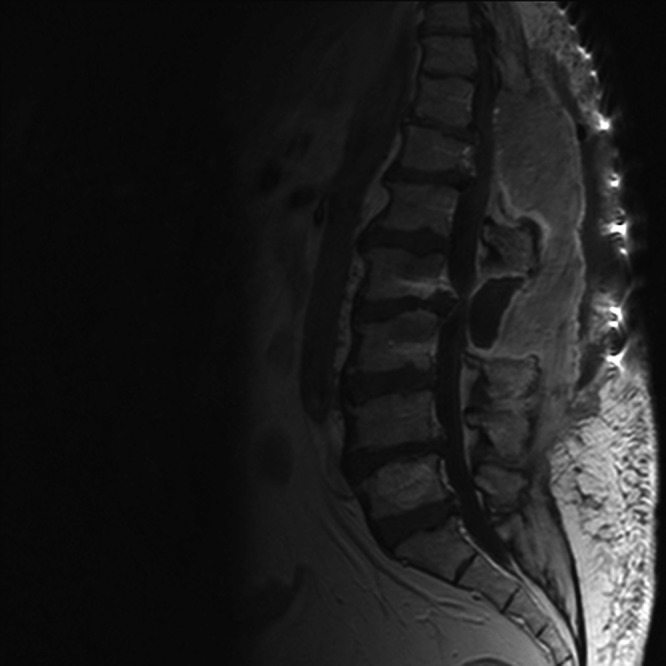

Although the wound healed and the infection resolved, the results of the blood tests worsened. The inflammatory markers increased: the ESR was 113 mm/h, and the CRP level was 13.7 mg/dl. The patient's temperature increased to 39°C, and she complained of back pain. The magnetic resonance image (MRI) scan demonstrated the presence of a large epidural abscess anterior to the L2 and L3 vertebrae, compressing the thecal sac (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of osteomyelitic involvement. The patient underwent drainage of her epidural abscess, and cultures of the pus grew pink-pigmented colonies on Columbia and chocolate agar plates after 48 h of incubation at 36°C. The isolate was catalase and urease positive and weakly oxidase positive, and it assimilated arabinose, malate, citrate, and glucose. In Gram-stained smears, the organisms appeared as Gram-negative, plump coccobacilli in pairs. The isolate was identified as Roseomonas gilardii by using the Vitek 2 automated system (bioMérieux, Marcy L'Etoile, France). Sequencing analysis of 1,455 nucleotides of the 16S rRNA genes (a nearly complete sequence) was performed, and the derived sequence was queried against GenBank. The results showed that our strain exhibited the highest similarity with the Roseomonas mucosa 16S rRNA gene sequences. Multiple alignments were performed using the ClustalW program, and a distance tree was derived using the neighbor-joining method (1) offered in the MEGA 5 software package (2). Results indicated that our strain (Roseomonas sp. strain SM14032013) clustered together with Roseomonas mucosa, Roseomonas massiliae, and Roseomonas terpenica species, while Roseomonas gilardii strains formed a distinct group (Fig. 2).

Fig 1.

Magnetic resonance image of the patient, demonstrating a large epidural abscess.

Fig 2.

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using 21 nearly complete sequences of 16S rRNA (>1,420 nt in length) of different Roseomonas strains that have been characterized to the species level and are listed in the GenBank nucleotide database. The alignment was done using the ClustalW software, and phylogenetic relations were inferred using the neighbor-joining method offered in the MEGA version 5 software (2). The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated species clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is shown next to each branch.

The agar gradient diffusion (Etest) method was employed to determine the in vitro susceptibility of the isolate. Since there are no published interpretative breakpoints for MICs specific for Roseomonas spp., the interpretative breakpoints for non-Enterobacteriaceae were applied (3). The isolate was found to be susceptible to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, tigecycline, chloramphenicol, minocycline, and co-trimoxazole and resistant to beta-lactams (penicillins and cephalosporins, except cefotaxime), fosfomycin, and colistin (Table 1). Vancomycin was discontinued and switched to parenteral meropenem, given for a total of 8 weeks.

Table 1.

Etest MICs for Roseomonas mucosa isolated from pus of the abscess

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Ampicillin | ≥256 |

| Ticarcillin | ≥256 |

| Ticarcillin-clavulanic acid | ≥256 |

| Piperacillin | ≥256 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≥256 |

| Cefuroxime | ≥256 |

| Cefotaxime | 4 |

| Ceftriaxone | ≥32 |

| Ceftazidime | ≥256 |

| Cefepime | ≥32 |

| Imipenem | 0.5 |

| Meropenem | 0.25 |

| Gentamicin | 0.125 |

| Amikacin | 0.75 |

| Tobramycin | 0.125 |

| Netilmicin | 0.19 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.047 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.125 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.064 |

| Chloramphenicol | 1.5 |

| Tetracycline | 0.5 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 0.032 |

| Minocycline | 0.094 |

| Tigecycline | 0.094 |

| Fosfomycin | ≥1024 |

| Colistin | ≥32 |

Gradually the patient's clinical condition improved, and laboratory values returned to normal. The patient was discharged in good physical condition.

The genus Roseomonas was first described in 1993 by Rihs et al. and comprises pink-pigmented, slow-growing, aerobic, Gram-negative, nonfermentative bacteria (4). The genus currently includes 17 species: R. mucosa, R. gilardii, R. cervicalis, R. aerilata, R. aerophila, R. aquatica, R. aestuarii, R. museae, R. frigidaquae, R. baikalica, R. lacus, R. ludipueritiae, R. rosea, R. riguiloci, R. stagni, R. terrae, and R. vinacea. R. mucosa was initially grouped with R. gilardii, but due to sufficient phylogenetic and phenotypic differences, it was reestablished as a distinct species in 2003 (5). Members of the genus are widely distributed in the environment in the air, water, and soil, but the natural reservoir of the microorganism is currently unknown (6). Roseomonas species generally have low virulence, although some species have been reported to cause serious infections in immunocompromised patients (7). When the organism is cultured from nonsterile body sites, it can be difficult to determine its clinical significance. In a retrospective review of Roseomonas infections, up to 40% of the isolates were not associated with disease (7). Similarly, a recent review reported that 25% of clinical isolates were not considered significant pathogens (8). This finding suggests that Roseomonas species may exist as transient colonizers of mucosal surfaces or contaminants of sterile body sites. Among isolates, R. mucosa and R. gilardii account for the vast majority of clinically significant infections (9). They are most commonly involved in bacteremias in patients with central venous catheters. Other, less common infections caused by Roseomonas include wound infections, vertebral osteomyelitis, arthritis, ventriculitis, and peritonitis associated with chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (10). The present case is the first example of an epidural abscess caused by Roseomonas mucosa. The source of the infection remained undetermined, because surveillance cultures were not performed.

Postoperative deep-surgical-site infection rates vary with the type of surgery and the anatomical site (11). The incidence of surgical site infection after decompressive laminectomy, diskectomy, and fusion is approximately 3% or lower. The addition of instrumentation increases the risk of infection to 12% (11). Additionally, posterior spinal surgery has higher rates of infection than anterior spinal surgery. This result is due to devascularization of paraspinal muscle produced by extensive muscle dissection and the large incisions required for instrument implantation (12). Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) is a rare but serious complication of spinal surgery. Gram-positive pathogens, especially Staphylococcus aureus, have been most commonly cultured from SEAs in adults. In a large series of patients with SEAs, S. aureus was reported to account for 86% of the SEAs overall (13). Among Gram-negative bacteria, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have commonly been implicated as causative pathogens of SEAs (13, 14).

Roseomonas species can easily be missed if cultures are not held for a prolonged time because of their slow growth in culture or misidentified by several identification systems. Presumptive identification of our isolate was obtained based on colonial morphology, Gram stain morphology, individual biochemical tests, and the Vitek 2 automated system. It was differentiated from Methylobacterium species, another pink-pigmented rod, by its inabilities to produce acid from methanol, to assimilate acetamide, or to absorb long-wave UV light (15). Definitive identification of the microorganism was performed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis using the Roseomonas 16S rRNA genes released in the GenBank data library. The constructed tree showed that R. mucosa and R. gilardii are clustered in clearly distinct phylogenetic groups, although they belong to the same branch, situated distantly from the other Roseomonas species. We also noticed that the distance between R. mucosa, R. terpenica, and R. massiliae is very small and that no clear distinction between these species can be drawn only from the 16S rRNA gene sequences.

Roseomonas is widely resistant to penicillins, such as ampicillin, ticarcillin, and piperacillin, and the addition of beta-lactamase inhibitors does not restore susceptibility (4–6). It is also resistant to cephalosporins, including broad-spectrum cephalosporins. However, Lewis et al. presented a series of in vitro tests of its susceptibility to cefotaxime and, in some cases, clinical responses to this agent (6). Richardson (15) and Singal et al. (16) reported isolates susceptible to narrow- and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. On the other hand, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and tetracycline are universally active against Roseomonas strains. In the present case, the isolate was resistant to all penicillins and cephalosporins (narrow-, expanded-, and broad-spectrum cephalosporins) tested except for cefotaxime, and it was susceptible to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, tigecycline, chloramphenicol, and minocycline. Our patient was successfully treated with meropenem.

In conclusion, although R. mucosa has been regarded as an opportunistic pathogen, it may rarely induce invasive infections even in immunocompetent patients. As this case illustrates, its broad antibiotic resistance and its ability to cause deep-surgical-site infections after posterior spinal surgery require R. mucosa to be considered a serious pathogen.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2012. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 22nd informational supplement. M100-S22 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rihs JD, Brenner DJ, Weaver RE, Steigerwalt AG, Hollis DG, Yu VL. 1993. Roseomonas, a new genus associated with bacteremia and other human infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:3275–3283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Han XY, Pham AS, Tarrand JJ, Rolston KV, Helser LO, Levett PN. 2003. Bacteriologic characterization of 36 strains of Roseomonas species and proposal of Roseomonas mucosa sp. nov. and Roseomonas gilardii subsp. rosea subsp. nov. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 120:256–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lewis L, Stock F, Williams D, Weir S, Gill VJ. 1997. Infections with Roseomonas gilardii and review of characteristics used for the biochemical identification and molecular typing. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 108:210–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Struthers M, Wong J, Janda JM. 1996. An initial appraisal of the clinical significance of Roseomonas species associated with human infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 23:729–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang CM, Lai CC, Tan CK, Huang YC, Chung KP, Lee MR, Hwang KP, Hsueh PR. 2012. Clinical characteristics of infections caused by Roseomonas species and antimicrobial susceptibilities of the isolates. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 72:199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dé I, Rolston KV, Han XY. 2004. Clinical significance of Roseomonas species isolated from catheter and blood samples: analysis of 36 cases in patients with cancer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1579–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schreckenberger PC, Daneshvar MI, Hollis DG. 2007. Acinetobacter, Achromobacter, Chryseobacterium, Moraxella, and other nonfermentative Gram-negative rods, p 770–802 In Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Pfaller MA. (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 9th ed American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meredith DS, Kepler CK, Huang RC, Brause BD, Boachie-Adjei O. 2012. Postoperative infections of the lumbar spine: presentation and management. Int. Orthop. 36:439–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schimmel JJP, Horsting PP, de Kleuver M, Wonders G, van Limbeek J. 2010. Risk factors for deep surgical site infections after spinal fusion. Eur. Spine J. 19:1711–1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tunkel AR. 2005. Subdural empyema, epidural abscess and suppurative intracranial thrombophlebitis, p 1164–1171 In Mandell GL, Benett JE, Dolin R. (ed), Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 6th ed Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang CR, Lu CH, Chuang YC, Chen SF, Tsai NW, Chang CC, Lui CC, Wang HC, Chien CC, Chang WN. 2011. Clinical characteristics and therapeutic outcome of Gram-negative bacterial spinal epidural abscess in adults. J. Clin. Neurosci. 18:213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richardson JD. 1997. Failure to clear a Roseomonas line infection with antibiotic therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 25:155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singal A, Malani PN, Day LJ, Pagani FD, Clark NM. 2003. Roseomonas infection associated with a left ventricular assist device. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 24:963–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]