Abstract

Neurodegeneration is a complex process involving different cell types and neurotransmitters. A common characteristic of neurodegenerative disorders is the occurrence of a neuroinflammatory reaction in which cellular processes involving glial cells, mainly microglia and astrocytes, are activated in response to neuronal death. Microglia do not constitute a unique cell population but rather present a range of phenotypes closely related to the evolution of neurodegeneration. In a dynamic equilibrium with the lesion microenvironment, microglia phenotypes cover from a proinflammatory activation state to a neurotrophic one directly involved in cell repair and extracellular matrix remodeling. At each moment, the microglial phenotype is likely to depend on the diversity of signals from the environment and of its response capacity. As a consequence, microglia present a high energy demand, for which the mitochondria activity determines the microglia participation in the neurodegenerative process. As such, modulation of microglia activity by controlling microglia mitochondrial activity constitutes an innovative approach to interfere in the neurodegenerative process. In this review, we discuss the mitochondrial KATP channel as a new target to control microglia activity, avoid its toxic phenotype, and facilitate a positive disease outcome.

1. An Imbalanced Four-Partite Synapse Crosstalk

The diversity of clinical phenotypes of neurodegenerative diseases share common neuropathological features that underlie significant modifications of the physiological glia-neuronal crosstalk. Over time, this leads to neuronal damage, specific pathway dysfunctions, and neurological disability [1]. Initially, the four-partite synapse, that is, the presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, presents a diversity of new communications that render and maintain a chronic neuroinflammation [1–3] with activation of various well-coordinated adaptive mechanisms to avoid or reverse damage [1, 3]. In fact, this imbalanced four-partite synapse crosstalk underlies the disease pathogenesis, and its progression—and also brain aging—reflects at each moment the contributions of each cell type. Because of that, higher perturbations are associated with significant molecular and cellular changes that lead to a progressive chronic neurodegenerative process from which return to physiological conditions is impossible [4]. As such, the disease progression represents the dynamic communicative process between all the synaptic participants in which the equilibrium between damaging and neuroprotective signals favors permanently and increasingly neuronal damage and synaptic loss.

The pivotal role of these four cell types in disease has yielded a huge amount of information to explain the dysfunction or disruption of neural circuits. At the present time, the working theories attribute key roles to protein misfolding, excitotoxicity, and mitochondrial dysfunction, this last one related to integrity, bioenergetics, calcium homeostasis, or reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. In fact, all these elements are interdependent, and all theories consider the participation of the same four-partite synapse organization, in which microglia, as a sensor and effector of CNS immune function, directly influence the disease initiation, progression, and outcome.

2. Microglia and Neurodegeneration

2.1. Misfolded Protein Diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases can be classified as misfolded protein diseases (MPD) because each one presents specific misfolded proteins. These proteins share no common sequence nor common structural identity between them and include the Protease-resistant Prion Protein, Polyglutamine, Amyloid-β, Tau protein, α-synuclein, superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), or fused in Sarcoma (FUS) [5, 6]. These misfolded proteins reveal a failure to adopt a proper protein folding due to an enhanced production of abnormal proteins or to a perturbation of cellular function and aging under the effects of ROS [7, 8]. In addition, their insufficient clearance also reflects a chronic impaired microglia autophagy resulting in accumulation of protein aggregates, cell damage, and progressive death [1, 9]. For example, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the misfolded proteins like SOD1 released initially from motor neurons activate microglia, and the ensuing neuronal injury depends upon a well-orchestrated dialogue between motor neurons and microglia [10]. Phagocytic microglial cells are very efficient scavengers but with a limited capacity towards α-synuclein aggregates [11, 12] characteristics for Lewy body disorders (LBDs), in particular for Parkinson's disease. The same microglia phagocytosis triggers the release of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and ROS, which may further promote neuronal dysfunction and degeneration and misfolded protein overload [13, 14]. In addition, microglia may also participate in the LBDs pathophysiology due to variations of their human leukocyte antigen region [15]. Thus, in all the different situations, the protein aggregates initiate and maintain a chronic activation of microglia as a constitutive element of MPD with their subsequent direct participation in neural damage through chronic ROS formation and cytokine secretion [16–18].

2.2. Excitotoxicity

Regarding excitotoxicity, the alterations of synaptic glutamate and calcium homeostasis lead to neuronal and glia glutamate receptor overactivation, culminating in neuronal death and progressive neural circuit dysfunctions [19, 20]. In this situation, three main compensatory responses are activated to avoid glutamate-induced damage [21]. Thus, the direct activation of the retaliatory systems, based on a coordinated increase of GABA, taurine, and adenosine signaling, will reduce glutamate receptor activation [22, 23], and the rapid adaptation of calcium homeostasis with the neuronal and astroglial formation of calcium precipitates will reduce the increased calcium signaling associated with glutamate [3, 24], and the reduction of glutaminase activity of the astrocyte-neuron glutamate/glutamine cycle will reduce glutamate level in the presynaptic neuron and synaptic glutamate activation [25]. Microglial cells are the glial cell type least susceptible to excitotoxicity, because they mostly express glutamate receptors when they are reactive. Injured neurons would directly activate microglia [26] by the release of a diversity of factors like galectin-3, [27], cystatin C, chemokine (C- X3-C motif) ligand 1 (CX3CL1) [28], or the danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) ligands that bind to Toll-like receptors (TLR) [29]. The benefits of such inflammation may be substantial to help avoid further neuronal damage if exposure to excitotoxicity is limited in time or intensity [25, 30]. Otherwhise, microglia effects will be deleterious through chronic ROS formation and cytokines secretion and directly related to the neurodegenerative process. With aging, this process will be potentiated by the senescent affectation of microglia, which changes cell morphology and functions [31–33]. In fact, cumulative evidence indicates a direct pathogenic role of senescent microglia in degenerative CNS diseases [34–36].

2.3. Energy Demand and Microglia Reaction

Microglia do not constitute a unique cell population but rather, present a range of phenotypes [1, 37] closely related to the evolution of the lesion process [33]. In a dynamic equilibrium with the lesion microenvironment, these phenotypes range from the well-known proinflammatory activation state to a neurotrophic one directly involved in cell repair and extracellular matrix remodeling [38], with a diversity of intermediary mixed phenotypes that present or not a phagocytic activity [39]. All these adaptative phenotypes relate directly to the evolution of the lesion, and variations in the expression of toxic, protective factors, and phagocytic activities greatly determine the outcome of the tissue [33, 37, 40].

In addition, microglia-like neurons present a high-energy demand, for which the lack of a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) repair system determines mtDNA cumulative defects with aging. As said previously, in these conditions, senescent microglia become increasingly dysfunctional and participates in the direct development of neurodegeneration [40, 41]. As in other cells, calcium signaling governs the communication between cytosol and mitochondria [42]. In macrophages, the phagocytic response represents a burst of ROS formation through an increased activity of the NADPH oxidase and also of mitochondria. The mitochondria ROS (mtROS) are potentiated by the translocated tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) [43] and its interaction with the ubiquitinated protein evolutionarily conserved signaling intermediate in Toll pathways (ECSIT) [44]. ECSIT associates with the oxidative phosphorylation complex I components and facilitates the assembly of the mitochondrial electron transport chain [44]. Thus, in macrophages, TRAF6 translocation induces the juxtaposition of phagosomes and mitochondria and potentiates mtROS formation and energy production [45]. A similar TRAF6 recruitment to mitochondria that engages ESCIT on the mitochondria surface is also observed in the same cells upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS, a TLR4 agonist) treatment [43].

In microglia, recruitment of cytoplasmic TRAF6 modulates LPS-evoked cytokine release [46]. The great similarity between peripheral and central immune systems, in particular between macrophages and microglia, makes a similar action of TRAF6 in microglia activated by LPS possible. If true, the mitochondria respiratory burst rending increased energy and ROS production in response to the elevated calcium required for the adoption of a specific microglia phenotype would also depend on TRAF6 translocation and interaction with ECSIT. And how calcium variations and TRAF6 interact to modulate their microglia effects should help identify the molecular pathways linked to the adoption of a phenotype or another one.

In parallel, a defect in the astrocyte-neuron crosstalk does not ensure sufficient neuronal supply of glucose, lactate, and oxygen, leading to increased neuronal damage, probably impossible to effectively repair [47]. This damage results in subsequent switch in microglia phenotype from an initial neuroprotective one to a final proinflammatory one and to the disease onset and progression [1].

Thus, whether microglia adopt a phenotype that will exacerbate tissue injury or one to promote brain repair and phagocytosis is likely to depend on the diversity of signals from the lesion environment and of the microglia response capacity [48, 49]. At each moment, microglia effectiveness to adapt to the changing synaptic signals and phagocytic needs to rapidly remove cellular debris depends on its accurate adaptation to match its immediate energy demand. This implies that to ensure and maintain an activated stage and adapt constantly their expression and function to a determined phenotype, microglia have to correspond permanently with a balanced ATP availability from aerobic glycolysis [50]. However, like in astrocytes, in reactive microglia, part of glucose renders ATP and lactate through anaerobic glycolysis. Thus, in the postulated four-partite synapse, lactate will be shuttling to neurons not only from astrocytes but also from microglia.

Mitochondrial bioenergetics depends on a proper stimulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to produce enough ATP to the cell and on the same mitochondria morphology [41, 51]. This requires a constant dynamic and rapid response of its array of individual mitochondria to adapt their shape and size to the microglia energy demand. Thus, via the combined fusion and fission events that are mediated by large guanosine triphosphatases, they improve their number and optimize their regional networks in order to deliver at each moment the needed ATP [52]. In microglia, a higher number of mitochondria mark the transition from microglia resting state to the activated one, as shown by an increased expression of the mitochondrial peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) labeled with (R)-PK11195 [53]. Both transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) procedures evidenced that this mitochondrial PBR complex functions as a pore, allowing the translocation of cholesterol and other molecules through the inner mitochondrial membrane [54]. Presently, the (R)-PK11195 ligand is commonly used to quantify microglia in brain sections from excitotoxic damage like stroke, brain trauma, epilepsy, or chronic neurodegenerative disorders [38, 55, 56] and also for PET detection as an in vivo marker of active disease [57].

The mtDNA is arranged in nucleoprotein complexes evenly distributed along the mitochondrial network [58]. Stimulation of mitochondrial fusion by mitofusin 1 and 2 and OPA1 maximizes oxidative phosphorylation because the fused mitochondria share and homogenize the content of all their compartments. Thus, when the mtDNA mutation load is minor, integration of defective mitochondria through fusion complementation increases their oxidative capacity by sharing RNA components and proteins, because the lack of a functional component in one mitochondria can be complemented by the presence of the component in another one [59]. If the mutation load is major, fission activation by Drp1 and Fis 1 increases the number of mitochondria and maintains their physiological functions removing the defective parts by mitophagy [60, 61]. Otherwise, abnormal mitochondrial network dynamics develop, rendering dysfunctional cells as a direct participant of the degenerative process. Presently, this physiopathological mechanism has not yet been evidenced in microglia. The known diseases associated with defects in mitochondria fusion-fission factors, like the OPA1-linked autosomal dominant optic atrophy, are genetic disorders, and not specific of microglia [62]. However, the blockade of glutamate-induced toxicity by antioxidants combined with inhibitors of glutamate uptake argues for a key role of ROS production in excitotoxicity [63]. Also, the importance of some inflammatory-independent neurodegenerative mechanisms associated with mitochondria dysfunction and oxidative stress in multiple sclerosis reinforces the possible participation of defective microglia function in the disease [64]. Thus, unraveling molecular mechanisms amenable to prevent or reverse defective microglia mitochondrial networks would open new possibilities to control neurodegenerative disorders.

The rise in cytosol calcium signaling associated with activation of glutamate and cytokine receptors of microglia match microglia cell energy demand with mitochondria supply. Upon activation, microglia express glutamine synthase (GS) and the two transporters EAAT-1 and -2 for glutamate and glutamine synaptic extrusion [65]. In mitochondria, glutamate and glutamine render oxoglutarate for the Krebs cycle and ammonium. At high concentration, ammonium contributes to the generation of superoxide, which after reaction with NO forms the highly reactive peroxynitrite [66]. The progressive reduction of neuronal glutaminase activity that parallels the switch from the apoptotic to the necrotic neuronal death [25] underlies a similar displacement of the glutamate/glutamine cycle toward a reduced glutamate formation and a net glutamine output [25]. So, the highest glutamine level present in necrosis renders more ammonium and more ROS production in microglia—adopting a mostly proinflammatory phenotype—damaging the surrounding cells and also their mitochondria network. This will cause microglia dysfunctions that may result in apoptosis [66].

Finally, stimulation of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), located in the inner membrane (MIM), promotes an active mitochondria calcium uptake [67]. Calcium moves down the MIM electrochemical gradient and, in the matrix, stimulates the rate limiting enzymes—pyruvate, isocitrate, and oxoglutarate dehydrogenases and also the ATP synthase—to render increased amounts of ATP and also of ROS [67–70]. Thus, whenever the cause of a major energy demand, a defective protein that does not allow a proper coordinated fission and fusion process induces a mitochondria dysfunction. This will cause a reduced cytosol ATP availability, an increased ROS production, major mtDNA dysfunctions, and a calcium dyshomeostasis, all of them resulting in a definitive loss of mitochondria network integrity and cell abnormalities [41, 71]. In view of the abovementioned theories, which all consider the participation of cellular and molecular multidirectional synaptic interactions, identification of therapeutic targets related to disease pathogenesis for the rationale design of treatments remains quite elusive. Modulation of microglia response by controlling their mitochondrial activity constitutes an innovative approach to interfere in the neurodegenerative process. The identification of a mitochondrial KATP channel expressed in human and rodents is a new target to control microglia activity, avoid their toxic phenotype, and facilitate a positive disease outcome.

3. KATP Channels in the CNS

KATP channels play important roles in many cellular functions by coupling cell metabolism to electrical activity with the participation of glucokinase. First detected in cardiac myocytes, they have been found in pancreatic β cells, skeletal and smooth muscle, neurons, pituitary, and tubular cells of the kidney [72–74]. In these tissues, KATP channels couple electrical activity to energy metabolism by regulating potassium fluxes across the cell membrane when glucose is available in sufficient conditions [75]. Increased energy metabolism leads to channel closure, membrane depolarization, and electrical activity. Conversely, metabolic inhibition opens KATP channels and suppresses electrical activity [76, 77].

Plasmalemmal KATP channels are assembled as a heterooctameric complex [78, 79] from two structurally distinct subunits: the pore forming inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Kir) subunit 6.1 or 6.2 and the regulatory sulphonylurea receptor (SUR). SUR, like all other ATP-Binding Cassette transporters, contains two transmembrane domains and two cytoplasmic ones (Nucleotide Binding Folds 1 and 2). Its N-terminal transmembrane domain mediates SUR-Kir6 interactions [80]. While ATP inhibits the KATP channel by direct binding to the cytoplasmic Kir6 domains [81], activators like Mg-nucleotides [82] potassium channel openers (KCOs) and inhibitors like sulfonylurea drugs [83] bind SUR to modulate the channel. KATP channels play a multitude of functional roles in the organism. In endocrine cells, they play an important role in hormone release, including insulin from pancreatic β cells [84] and glucagon from pancreatic α cells [85]. Epithelial cells of blood vessels also express KATP channels, where they are involved in the control of blood flow and cerebrovascular processes [86].

In the brain, neuronal expression of KATP has been described in the substantia nigra, the neocortex, hippocampus, and hypothalamus [72, 74]. In these areas, KATP channels modulate electrical activity and neurotransmitter release [87], protect against seizures [88], and play an essential role in the control of glucose homeostasis [82]. The expression of KATP channels has also been suggested in microglia [89]. As discussed in Section 4, our previous studies showed that reactive microglia increase their expression of the KATP-channel components Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1, and SUR2B after brain pathologies such as stroke and Alzheimer's disease (AD) [90–92].

Finally, KATP channels have also been described in the mitochondria, located on the inner membrane of these organelles where they play a crucial role in the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis and of the proton gradient involved in the respiratory chain [93, 94].

3.1. KATP Channel Gating and Pharmacology

The octameric structure of the KATP channel with four inhibitory ATP-binding sites per channel (one on each Kir6.2 subunit) and eight stimulatory Mg-nucleotide-binding sites on SUR [95] represents a complex regulation by nucleotides. The same for the channel kinetics, with a large number of kinetic states, as its activity reflects at each moment the result of the nucleotide effects at each site. Several endogenous ligands bind the KATP channel subunits: ATP (with or without Mg2+) inhibits the Kir6.2 subunits, and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate activates them; sulphonylureas inhibit the SUR subunits, and KCO drugs activate them. In addition, in the presence of Mg2+, ATP and ADP can activate the channel through interaction with the nucleotide-binding folders of SUR [83]. Inhibition by ATP binding to Kir6.2 and activation by Mg-nucleotides is probably the first physiological regulatory mechanism [82].

In recent years, KATP channels have attracted increasing interest as targets for drug development. Their pivotal role in a plethora of physiological processes has been underscored by recent discoveries linking potassium channel mutations to various diseases. The second generation of KCOs or potassium channel blockers, with an improved in vitro or in vivo selectivity, has broadened the chemical diversity of KATP channel ligands. However, despite this significant progress, a lot of work remains to be done to fully exploit the pharmacological potential of KATP channels and their KCOs or potassium channel blocker ligands. Sulfonylureas that bind KATP channel are oral hypoglycemic agents widely used in the treatment of type II diabetes mellitus [96]. For example, glibenclamide binds with subnanomolar or nanomolar affinity and is a potent inhibitor of SUR1-regulated channel activity [97]. SUR1-regulated channels are exquisitely sensitive to changes in the metabolic state of the cell, responding to physiologically meaningful changes in intracellular ATP concentration by modulating channel open probability [98].

On the other hand, considering the unique role that KATP channels play in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis, the KCOs family adds its potential in promoting cellular protection under conditions of metabolic stress to the already existing pharmacotherapy. Preclinical evidence indicates a broad therapeutic potential for KCOs in hypertension, cardiac ischemia, asthma, or urinary incontinence to mention a few. For example, diazoxide (7-chloro-3-methyl-4H-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide) is a small molecule well known to activate KATP channels in the smooth muscle of blood vessels and pancreatic β cells by increasing membrane permeability to potassium ions. Diazoxide binds with similar affinities to SUR1 and SUR2B on the interplay between SUR and Kir subunits, a site different of the other KCOs binding sites [83, 99], and its hyperpolarization of cell membranes prevents calcium entry via voltage-gated calcium channels, resulting in vasorelaxation and the inhibition of insulin secretion [100]. For all this, diazoxide has been approved and used since the 1970s for treating malignant hypertension and hypoglycemia in most European countries, the USA, and Canada [101, 102].

4. The Mitochondrial KATP Channel

More than 20 years ago, a putative mitochondrial KATP (mitoKATP) channel was proposed, both functionally and molecularly distinct from the one in the plasma membrane [103]. Initially, functional mitoKATP channels were thought to be composed in brain of Kir6.1 or Kir6.2, and SUR2B [104–106] and diazoxide or nicorandil have been proposed as specific mitoKATP channel openers, whereas 5-hydroxydecanoate would specifically block this channel type [107–111].

Some authors have questioned the existence of the mitoKATP channel since they failed to detect its existence in isolated heart and brain mitochondria [112, 113], and the specificity of diazoxide and 5-hydroxydecanoate has been questioned [114, 115]. According to these authors, the lack of specific effects of diazoxide could indicate that mitoKATP channels are not present in mitochondria and that the pharmacological effects of diazoxide and 5-hydroxydecanoate are caused by interaction with other pharmacological or unspecific targets (see [116] for a review). However, one must consider that the variable findings can depend on minor differences in mitochondrial isolation procedures, since the channel may be inactivated during isolation of mitochondria, or a cofactor that needs to be present may be lost [113]. Moreover, the nonspecific effects of diazoxide are observed in vitro when very high concentrations are used (higher than 50 μM). Since in rat heart mitochondria, diazoxide is found to open mitochondrial KATP channels with a half-maximal saturation of 2.3 μM [94]. These concentrations are in excess compared with those described to promote mitochondrial KATP channel opening [117, 118].

Putative tissue heterogeneity of mitoKATP channel expression must also be taken into account to explain the specificity of diazoxide actions. For instance, expression of KATP channel components was not detected in resting microglia of rat and human brain, whereas activated cells in ischemic rats and AD patients presented strong labeling for SUR and Kir components in the cytoplasm and plasmalemma [90–92]. In this line, diazoxide prevents apoptosis of epithelial cells in the aorta of diabetic rats compared to controls [119]. Thus, in physiological conditions, very low expression of mitoKATP channels in cardiac tissue or neurons may render cells refractory to low diazoxide concentrations, whereas these tissues may increase the channel expression in pathological conditions.

Within this controversy, a major problem is that the molecular identity of mitoKATP has not yet been determined. A recent study has presented strong proteomic and pharmacological evidence of kcnj1 as a pore-forming subunit of mitoKATP channels [120]. This result supports the existence of specific mitoKATP channels and should help to explain the tissue specificity of different KCOs and clarify why some authors found mitoKATP channels sensitive to drugs that do not affect the plasmalemmal KATP one [121].

Because SUR1-regulated channels are exquisitely sensitive to changes in the metabolic state of the cell and that microglia are permanently sensing the environment, the expression of KATP channels in activated microglia will couple cell energy to membrane potential and microglia response with the adoption of a specific phenotype to the surrounding signals. This channel expression may then be critical in determining, at least in part, microglia participation in the pathogenic process.

4.1. MitoKATP Channels in Neurodegeneration

Our laboratory has described the expression of KATP channels in microglia [1, 90, 91], which control the release of a diversity of inflammatory mediators, such as nitric oxide (NO), interleukine-6, or TNF-α [122]. In a rat model of neurodegeneration and in postmortem samples of patients with AD, we also reported that activated microglia strongly expressed KATP channel SUR components [90] and that reactive microglia increase their expression of the KATP channel components Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1, and SUR2B after brain insults [92, 122]. In this context, controlling the extent of microglial activation may offer prospective clinical therapeutic benefits for inflammation-related neurodegenerative disorders. We and other authors have documented that pharmacological activation of KATP channels can exert neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects on the brain against ischemia, trauma, and neurotoxicants [123–126].

Diazoxide has evidenced prevention of rotenone-induced microglial activation and production of TNF-α and prostaglandin E2 in cultured BV2 microglia [126]. Also, diazoxide inhibited in vitro NO, TNF-α, interleukin-6 production, and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by LPS-activated microglia. In mitochondria isolated from these cells, diazoxide also alleviated rotenone-induced mitochondrial membrane potential loss [126], for which mitoKATP channels participate in the regulation of microglial proinflammatory activation.

In vivo studies have confirmed that diazoxide exhibits neuroprotective effects against rotenone, along with the inhibition of microglial activation and neuroinflammation, without affecting cyclooxygenase-2 expression and phagocytosis [126]. When tested in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) murine model of multiple sclerosis, 1 mg/kg oral diazoxide ameliorated EAE clinical signs but did not prevent disease. A significant reduction in myelin and axonal loss accompanied by a decrease in glial activation and neuronal damage was observed. In this model, diazoxide did not affect the number of infiltrating lymphocytes positive for CD3 and CD20 in the spinal cord [122]. Finally, diazoxide has been tested in the triple transgenic mouse model of AD (3xTg-AD) that harbors three AD-related genetic loci: human PS1M146V, human APPswe, and human tauP301L [127], and 3xTgAD mice treated with 10 mg/kg/day diazoxide for 8 months exhibited improved performance in the Morris water maze test and decreased accumulation of Aβ oligomers and hyperphosphorylated Tau in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus [128]. In turn, exposition to Aβ oligomers increases the neuronal expression of KATP channels. With time, this increase is specific for Kir6.1 and SUR2 components [129], which suggest that Aβ oligomers induce differential regulations of KATP subunit neuronal expression. Exposed to Aβ oligomers, the continuous oxidative stress results in neuronal severe mitochondria dysfunction [130, 131], and the expression changes of KATP channel components may reflect neuronal attempts to resist the insult in accordance with the metabolic state.

The chronic glutamate-mediated overexcitation of neurons is a newer concept that has linked excitotoxicity to neurodegenerative processes in ALS, Huntington's disease, AD, and Parkinson's disease [19]. Such a chronic excitotoxic process can be triggered by a dysfunction of glutamate synapses, due to an anomaly at the presynaptic, postsynaptic, or astroglial levels [21]. The contribution of excitotoxicity to the neurodegenerative process can be reproduced by the microinjection of low doses of glutamate agonist into the rodent brain. Due to the high affinity of ionotropic glutamate receptors for their specific agonists, such as N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), these drugs injected in non-saturable conditions can trigger calcium-mediated excitotoxicity in several rat brain areas and induce an ongoing neurodegenerative process [55, 56, 132, 133].

For example, any microinjection of NMDA in the rat hippocampus triggers a persistent process that leads to progressive hippocampal atrophy with a widespread neuronal loss and a concomitant neuroinflammation [133]. This paradigm also mimics the alterations of other neurotransmitter systems and neuromodulators found in human neurodegeneration [22].

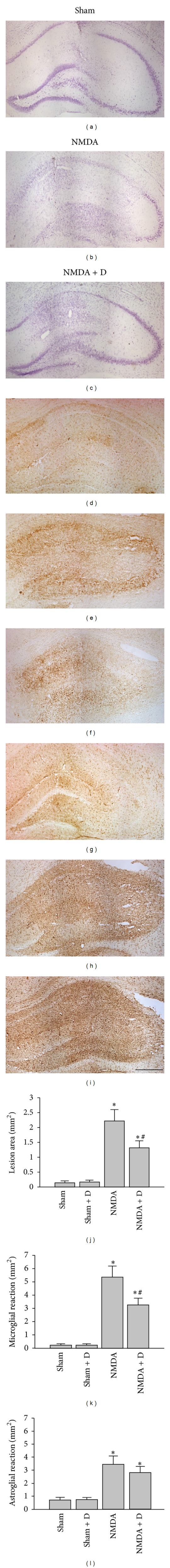

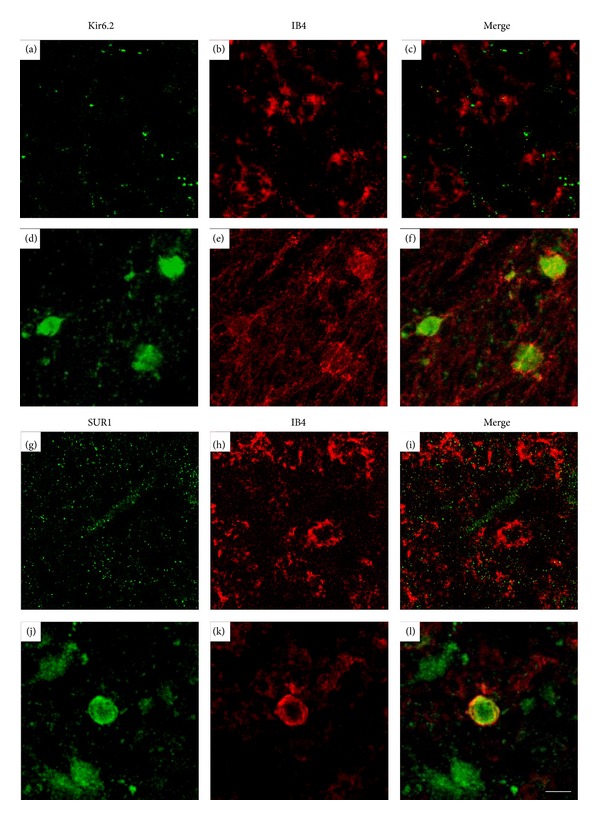

This neurodegenerative NMDA-induced hippocampal process is also attenuated by diazoxide oral treatment, which ameliorated microglia-mediated inflammation and reduced neuronal loss (Figure 1). In this model, anti-SUR1 and anti-Kir6.2 antibodies immunostained both the plasmalemma membrane and the perinuclear space of amoeboid reactive microglia (Figure 2), suggesting that microglial activation involves expression and translocation of SUR1 from its internal reservoir toward the cell surface and the mitochondria. Increased expression and translocation of the KATP channel to the cell surface were also detected by specific binding of fluorescently tagged glibenclamide (glibenclamide BODIPY FL; green fluorescence) to SUR1 in rat primary microglial cultures [92].

Figure 1.

Effect of diazoxide treatment on the NMDA-induced hippocampal lesion. Microphotographs of Nissl-stained sections of a rat hippocampus 15 days after the injection of 0.5 μL of (a) vehicle, (b) 40 mM NMDA, and (c) 40 mM NMDA and treated with 1 mg/kg/day diazoxide p.o. Note that treatment with diazoxide decreased NMDA induced hippocampal lesion. (d) Isolectin B4 histochemistry (IB4) staining of microglia in the hippocampus of sham rats, (e) NMDA-lesioned rats, and (f) NMDA rats treated with diazoxide. Note that treatment with diazoxide decreased the area of enhanced IB4 staining. GFAP immunostaining of the astrocytes in the hippocampus of (g) sham rats, NMDA-lesioned rats (h), and NMDA rats treated with diazoxide (i). Histograms show the quantification of the diazoxide effects in the area of lesion (j), area of microgliosis (k), and area of astrogliosis (l) in the hippocampus of NMDA-lesioned rats. Sham refers to rats injected with vehicle (50 mM PBS, pH 7.4), NMDA refers to rats injected with 0.5 μL of 40 mM NMDA in the hippocampus, and NMDA + D refers to NMDA-injected rats treated with 1 mg/kg/day diazoxide p.o. from postlesion day 5 to 15. Stereotaxic coordinates were −3.3 mm and 2.2 mm from bregma and −2.9 mm from dura [25]. All animals were manipulated in accordance with the European legislation (86/609/EEC), N = 6 rats/group. Scale bar 1 mm. *P < 0,05 compared to sham, # P < 0,05 compared to NMDA, LSD (posthoc test).

Figure 2.

Expression of KATP channel components SUR1 and Kir6.2 in activated IB4-positive cells into the core of the hippocampal lesion (Bregma −3.3). ((a)–(f)) Confocal photomicrographs of hippocampal sections immunostained with IB4 and anti-Kir6.2 antibodies in control ((a)–(c)) and NMDA-lesioned rats ((d)–(f)). ((g)–(l)) Confocal photomicrographs of hippocampal sections immunostained with IB4 anti-SUR1 antibodies in control ((g)–(i)) and NMDA-lesioned rats ((j)–(l)). Note that reactive amoeboid microglia stained with IB4 show specific immunostaining with anti-Kir6.2 and anti-SUR1 antibodies in the cell membrane but also in the cytoplasm. For lesion details, see legend of Figure 1. Scale bar 10 μm.

Therefore, the expression of mitoKATP channels by activated microglia indicates that KCOs, such as diazoxide, could be used as therapeutic agents to treat inflammatory processes of neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, or AD.

4.2. MitoKATP Channels Modulate Microglia Reaction

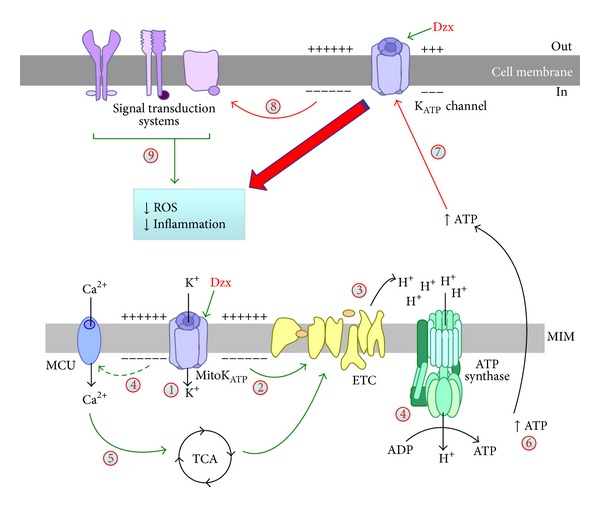

As explained, depending on the nature of the damage, microglial activation may take place, initially expressing neuroprotective signals to help avoid further neuronal death, but then changing progressively to an inflammatory phenotype [33]. The neuroprotective effects of diazoxide are proposed to modulate the inflammatory microglial activation, without affecting cyclooxygenase-2 expression and phagocytosis [122, 126]. The mechanism of action of diazoxide and other KCOs has not been completely elucidated yet. However, the diazoxide-mediated neuroprotection is supposed to be mediated by its interactions with mitochondria, which are the main ATP-generating sites in microglial cells. In chronically reactive microglia, diazoxide increases potassium flux into the mitochondrial matrix [117, 118] by activation of mitoKATP channels, which depolarize the MIM and preserve mitochondrial structural and functional integrity [132]. Indeed, cells treated with diazoxide demonstrate a favorable energetic profile with limited damage following stress challenges [108, 134], and mitoKATP channel opening promotes translocation of H+ through the MIM, underscoring the protonophoric uncoupling and enhancing ATP synthesis (Figure 3). As a proposed mechanism, mitoKATP channels opening serves to maintain constant volume and avoid an excessive mitochondrial contraction that is deleterious for electron transport [117, 118]. Thus, mitoKATP channel opening may prevent respiratory inhibition due to matrix contraction that would otherwise occur during high rates of ATP synthesis. The increased H+ gradient also constitutes the energy source for calcium transport through the MCU towards the mitochondrial matrix [67]. This calcium controls the malate/aspartate transport and dehydrogenases from the tricarboxylic acid cycle, which finally results in increased production of NADH, the electron donor of the respiratory chain. As a result, diazoxide increases the ATP/ADP ratio in the mitochondria and cytoplasm [135] of reactive microglia. ATP closes the KATP channels from the plasma membrane preventing electrical activity and modifying the cell response to tissue injury. However, specific action of diazoxide on plasmalemma KATP channel must not be discarded, and the activity of KATP channel in the membrane will result from a compromise between the ATP-mediated inhibition and the diazoxide-induced opening (Figure 3). As a result, the cell response to tissue injury includes a decreased synthesis of proinflammatory molecules and suppression of mitochondria-derived ROS [126] that result in a maintenance of the mitochondria network integrity and of the phagocytic activity.

Figure 3.

Diazoxide modifies microglial reactivity in the brain. Drawing of the effects of mitochondrial KATP (mitoKATP) channel opening in the energy metabolism and its consequences in the microglia reaction during neurodegeneration. (1) Diazoxide activates mitoKATP channels, which (2) depolarizes the mitochondrial internal membrane (MIM), and (3) induces translocation of H+ by the electron transport chain (ETC) that enhances both ATP synthesis and activation of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) (4). Calcium in the mitochondria activates dehydrogenases of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) (5) that also enhances ATP production (6). ATP closes the KATP channel from the plasma membrane (7), while diazoxide opens the channel. As a result, the cell response to activation signals decreases (8), leading to a reduction of the ROS generation and the inflammatory response (9) of reactive microglia (see the text for details).

Thus, control of mitochondria activity by mitoKATP channel opening decreases the microglia cytotoxic activity and prevents overactivation of these cells during neurodegeneration. This therapeutic approach may keep the microglia inflammatory activity under the cytotoxic threshold throughout the course of the disease, avoiding amplification of the progressive neuronal loss over time and facilitating a positive disease outcome.

Disclosure

NM and MJR have applied for a PCT application (application no. PCT/EP2011/050049). The other authors report no disclosure.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant PT-2011-1091-900000 from the Ministerio de Economia e Innovación and by Grant 2009SGR1380 from the Generalitat de Catalunya (Autonomous Government), Spain.

References

- 1.Ortega FJ, Vidal-Taboada J, Mahy N, Rodriguez MJ. Brain Damage—Bridging Between Basic Research and Clinics. chapter 7. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech Open Access Publisher Rijeka; 2012. Molecular mechanisms of acute brain injury and ensuing neurodegeneration; pp. 163–186. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Stevens B. The “quad-partite” synapse: microglia-synapse interactions in the developing and mature CNS. Glia. 2013;61(1):24–36. doi: 10.1002/glia.22389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vidal-Taboada J, Mahy N, Rodriguez MJ. Neurodegenerative Diseases—Processes, Prevention, Protection and Monitoring. chapter 13. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech Open Access Publisher Rijeka; 2011. Microglia, calcification and neurodegenerative diseases; pp. 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garden GA, La Spada AR. Intercellular (Mis)communication in neurodegenerative disease. Neuron. 2012;73(5):886–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Neurodegenerative diseases: a decade of discoveries paves the way for therapeutic breakthroughs. Nature Medicine. 2004;10(10):1055–1063. doi: 10.1038/nm1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morales R, Estrada LD, Diaz-Espinoza R, et al. Molecular cross talk between misfolded proteins in animal models of alzheimer’s and prion diseases. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(13):4528–4535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5924-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drew SC, Masters CL, Barnham KJ. Alzheimer’s Aβ peptides with disease-associated NTerminal modifications: influence of isomerisation, truncation and mutation on Cu2+ coordination. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015875.e15875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor JP, Hardy J, Fischbeck KH. Toxic proteins in neurodegenerative disease. Science. 2002;296(5575):1991–1995. doi: 10.1126/science.1067122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J. Microglial dysfunction and defective β-amyloid clearance pathways in aging alzheimer’s disease mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(33):8354–8360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appel SH, Zhao W, Beers DR, Henkel JS. The microglial-motoneuron dialogue in ALS. Acta Myologica. 2011;30:4–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackenzie IRA. Activated microglia in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2000;55(1):132–134. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H, Suk J, Bae E, Lee S. Clearance and deposition of extracellular α-synuclein aggregates in microglia. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;372(3):423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deleidi M, Hallett PJ, Koprich JB, Chung C, Isacson O. The toll-like receptor-3 agonist polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid triggers nigrostriatal dopaminergic degeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(48):16091–16101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2400-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koprich JB, Reske-Nielsen C, Mithal P, Isacson O. Neuroinflammation mediated by IL-1β increases susceptibility of dopamine neurons to degeneration in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2008;5, article 8 doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orr CF, Rowe DB, Mizuno Y, Mori H, Halliday GM. A possible role for humoral immunity in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2005;128(11):2665–2674. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deleidi M, Maetzler W. Protein clearance mechanisms of alpha-synuclein and amyloid-beta in lewy body disorders. International Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2012;2012:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/391438.391438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zilka N, Stozicka Z, Kovac A, Pilipcinec E, Bugos O, Novak M. Human misfolded truncated tau protein promotes activation of microglia and leukocyte infiltration in the transgenic rat model of tauopathy. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2009;209(1-2):16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandrekar S, Jiang Q, Lee CYD, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Holtzman DM, Landreth GE. Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble aβ through fluid phase macropinocytosis. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(13):4252–4262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau A, Tymianski M. Glutamate receptors, neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration. Pflugers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 2010;460(2):525–542. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0809-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obrenovitch TP, Urenjak J, Zilkha E, Jay TM. Excitotoxicity in neurological disorders—the glutamate paradox. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2000;18(2-3):281–287. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodríguez MJ, Pugliese M, Mahy N. Drug abuse, brain calcification and glutamate-induced neurodegeneration. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2009;2(1):99–112. doi: 10.2174/1874473710902010099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodríguez MJ, Robledo P, Andrade C, Mahy N. In vivo co-ordinated interactions between inhibitory systems to control glutamate-mediated hippocampal excitability. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;95(3):651–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sapolsky RM. Cellular defenses against excitotoxic insults. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;76(6):1601–1611. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodríguez MJ, Bernal F, Andrés N, Malpesa Y, Mahy N. Excitatory amino acids and neurodegeneration: a hypothetical role of calcium precipitation. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2000;18(2-3):299–307. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramonet D, Rodríguez MJ, Fredriksson K, Bernal F, Mahy N. In vivo neuroprotective adaptation of the glutamate/glutamine cycle to neuronal death. Hippocampus. 2004;14(5):586–594. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biber K, Neumann H, Inoue K, Boddeke HWGM. Neuronal “On” and “Off” signals control microglia. Trends in Neurosciences. 2007;30(11):596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutta G, Barber DS, Zhang P, Doperalski NJ, Liu B. Involvement of dopaminergic neuronal cystatin C in neuronal injury-induced microglial activation and neurotoxicity. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2012;122:752–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streit WJ. Microglia and neuroprotection: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Research Reviews. 2005;48(2):234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sloane JA, Blitz D, Margolin Z, Vartanian T. A clear and present danger: endogenous ligands of Toll-like receptors. NeuroMolecular Medicine. 2010;12(2):149–163. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends in Immunology. 2004;25(12):677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stolzing A, Grune T. Impairment of protein homeostasis and decline of proteasome activity in microglial cells from adult wistar rats. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2003;71(2):264–271. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stolzing A, Widmer R, Jung T, Voss P, Grune T. Tocopherol-mediated modulation of age-related changes in microglial cells: turnover of extracellular oxidized protein material. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2006;40(12):2126–2135. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graeber MB, Streit WJ. Microglia: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathologica. 2010;119(1):89–105. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J, Connor KM, Smith LEH. Overstaying their welcome: defective CX3CR1 microglia eyed in macular degeneration. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(10):2758–2762. doi: 10.1172/JCI33513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croisier E, Graeber MB. Glial degeneration and reactive gliosis in alpha-synucleinopathies: the emerging concept of primary gliodegeneration. Acta Neuropathologica. 2006;112(5):517–530. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0119-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Streit WJ, Braak H, Xue Q, Bechmann I. Dystrophic (senescent) rather than activated microglial cells are associated with tau pathology and likely precede neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2009;118(4):475–485. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0556-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz M, Butovsky O, Brück W, Hanisch U. Microglial phenotype: is the commitment reversible? Trends in Neurosciences. 2006;29(2):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Yebra L, Malpesa Y, Ursu G, et al. Dissociation between hippocampal neuronal loss, astroglial and microglial reactivity after pharmacologically induced reverse glutamate transport. Neurochemistry International. 2006;49(7):691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dirscherl K, Karlstetter M, Ebert S, et al. Luteolin triggers global changes in the microglial transcriptome leading to a unique anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective phenotype. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2010;7, article 3 doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Block ML, Zecca L, Hong J. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(1):57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desler C, Rasmussen LJ. Mitochondria in biology and medicine. Mitochondrion. 2012;12(4):472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Csordás G, Hajnóczky G. SR/ER-mitochondrial local communication: calcium and ROS. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1787(11):1352–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.West AP, Brodsky IE, Rahner C, et al. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2011;472(7344):476–480. doi: 10.1038/nature09973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogel RO, Janssen RJRJ, van den Brand MAM, et al. Cytosolic signaling protein Ecsit also localizes to mitochondria where it interacts with chaperone NDUFAF1 and functions in complex I assembly. Genes & Development. 2007;21(5):615–624. doi: 10.1101/gad.408407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochemical Journal. 2009;417(1):1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prinz M, Hanisch U. Murine microglial cells produce and respond to interleukin-18. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;72(5):2215–2218. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allaman I, Bélanger M, Magistretti PJ. Astrocyte-neuron metabolic relationships: for better and for worse. Trends in Neurosciences. 2011;34(2):76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halliday GM, Stevens CH. Glia: initiators and progressors of pathology in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2011;26(1):6–17. doi: 10.1002/mds.23455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henkel JS, Beers DR, Zhao W, Appel SH. Microglia in ALS: the good, the bad, and the resting. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2009;4(4):389–398. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernhart E, Kollroser M, Rechberger G, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid receptor activation affects the C13NJ microglia cell line proteome leading to alterations in glycolysis, motility, and cytoskeletal architecture. Proteomics. 2010;10(1):141–158. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ulivieri C. Cell death: insights into the ultrastructure of mitochondria. Tissue and Cell. 2010;42(6):339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Youle RJ, van der Bliek AM. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science. 2012;337(6098):1062–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.1219855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cahard D, Canat X, Carayon P, Roque C, Casellas P, Le Fur G. Subcellular localization of peripheral benzodiazepine receptors on human leukocytes. Laboratory Investigation. 1994;70(1):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papadopoulos V, Boujrad N, Ikonomovic MD, Ferrara P, Vidic B. Topography of the Leydig cell mitochondrial peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1994;104:R5–R9. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernal F, Petegnief V, Rodríguez MJ, Ursu G, Pugliese M, Mahy N. Nimodipine inhibits TMB-8 potentiation of AMPA-induced hippocampal neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2009;87(5):1240–1249. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petegnief V, Ursu G, Bernal F, Mahy N. Nimodipine and TMB-8 potentiate the AMPA-induced lesion in the basal ganglia. Neurochemistry International. 2004;44(4):287–291. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(03)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Banati RB, Newcombe J, Gunn RN, et al. The peripheral benzodiazepine binding site in the brain in multiple sclerosis. Quantitative in vivo imaging of microglia as a measure of disease activity. Brain. 2000;123(11):2321–2337. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.11.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malka F, Lombès A, Rojo M. Organization, dynamics and transmission of mitochondrial DNA: focus on vertebrate nucleoids. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1763(5-6):463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takai D, Isobe K, Hayashi J. Transcomplementation between different types of respiration-deficient mitochondria with different pathogenic mutant mitochondrial DNAs. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(16):11199–11202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kubli DA, Gustafsson AB. Mitochondria and mitophagy: the yin and yang of cell death control. Circulation Research. 2012;111(9):1208–1221. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santos D, Cardoso SM. Mitochondrial dynamics and neuronal fate in Parkinson's disease. Mitochondrion. 2012;12(4):428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Bergen NJ, Crowston JG, Kearns LS, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation compensation may preserve vision in patients with OPA1-linked autosomal dominant optic atrophy. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021347.e21347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matute C, Domercq M, Sánchez-Gómez M. Glutamate-mediated glial injury: mechanisms and clinical importance. Glia. 2006;53(2):212–224. doi: 10.1002/glia.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fischer MT, Sharma R, Lim JL, et al. NADPH oxidase expression in active multiple sclerosis lesions in relation to oxidative tissue damage and mitochondrial injury. Brain. 2012;135(3):886–899. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gras G, Porcheray F, Samah B, Leone C. The glutamate-glutamine cycle as an inducible, protective face of macrophage activation. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2006;80(5):1067–1075. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Svoboda N, Kerschbaum HH. L-Glutamine-induced apoptosis in microglia is mediated by mitochondrial dysfunction. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;30(2):196–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rizzuto R, De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Mammucari C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signaling. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012;13(9):566–578. doi: 10.1038/nrm3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hansford RG. Physiological role of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 1994;26(5):495–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00762734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCormack JG, Denton RM. The effects of calcium ions and adenine nucleotides on the activity of pig heart 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Biochemical Journal. 1979;180(3):533–544. doi: 10.1042/bj1800533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCormack JG, Halestrap AP, Denton RM. Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiological Reviews. 1990;70(2):391–425. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rossignol R, Gilkerson R, Aggeler R, Yamagata K, Remington SJ, Capaldi RA. Energy substrate modulates mitochondrial structure and oxidative capacity in cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2004;64(3):985–993. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ashford MLJ, Boden PR, Treherne JM. Glucose-induced excitation of hypothalamic neurones is mediated by ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Pflugers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 1990;415(4):479–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00373626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kefaloyianni E, Bao L, Rindler MJ, et al. Measuring and evaluating the role of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in cardiac muscle. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2012;52(3):596–607. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levin BE. Glucosensing neurons do more than just sense glucose. International Journal of Obesity. 2001;25(5):S68–S72. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kline CF, Kurata HT, Hund TJ, et al. Dual role of KATP channel C-terminal motif in membrane targeting and metabolic regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(39):16669–16674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907138106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Craig TJ, Ashcroft FM, Proks P. How ATP inhibits the open KATP channel. Journal of General Physiology. 2008;132(1):131–144. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nichols CG, Lederer WJ. Adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels in the cardiovascular system. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261(6):H1675–H1686. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.6.H1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Proks P, Ashcroft FM. Modeling KATP channel gating and its regulation. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 2009;99(1):7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wheeler A, Wang C, Yang K, et al. Coassembly of different sulfonylurea receptor subtypes extends the phenotypic diversity of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels. Molecular Pharmacology. 2008;74(5):1333–1344. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chan KW, Zhang H, Logothetis DE. N-terminal transmembrane domain of the SUR controls trafficking and gating of Kir6 channel subunits. The EMBO Journal. 2003;22(15):3833–3843. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft FM. Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387(6629):179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440(7083):470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.M. Ashcroft F, M. Gribble F. New windows on the mechanism of action of KATP channel openers. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2000;21(11):439–445. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01563-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ashcroft FM, Harrison DE, Ashcroft SJH. Glucose induces closure of single potassium channels in isolated rat pancreatic β-cells. Nature. 1984;312(5993):446–448. doi: 10.1038/312446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Göpel SO, Kanno T, Barg S, Weng X-G, Gromada J, Rorsman P. Regulation of glucagon release in mouse α-cells by KATP channels and inactivation of TTX-sensitive Na+ channels. Journal of Physiology. 2000;528(3):509–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosenblum WI. ATP-sensitive potassium channels in the cerebral circulation. Stroke. 2003;34(6):1547–1552. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000070425.98202.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Avshalumov MV, Rice ME. Activation of ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels by H2O2 underlies glutamate-dependent inhibition of striatal dopamine release. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(20):11729–11734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834314100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamada K, Juan Juan Ji JJJ, Yuan H, et al. Protective role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in hypoxia-induced generalized seizure. Science. 2001;292(5521):1543–1546. doi: 10.1126/science.1059829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McLarnon JG, Franciosi S, Wang X, Bae JH, Choi HB, Kim SU. Acute actions of tumor necrosis factor-α on intracellular Ca2+ and K+ currents in human microglia. Neuroscience. 2001;104(4):1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ramonet D, Rodríguez MJ, Pugliese M, Mahy N. Putative glucosensing property in rat and human activated microglia. Neurobiology of Disease. 2004;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ortega FJ, Gimeno-Bayon J, Espinosa-Parrilla JF, et al. ATP-dependent potassium channel blockade strengthens microglial neuroprotection after hypoxia-ischemia in rats. Experimental Neurology. 2012;235(1):282–296. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ortega FJ, Jolkkonen J, Mahy N, Rodríguez MJ. Glibenclamide enhances neurogenesis and improves long-term functional recovery after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2013;33:356–364. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ardehali H, O’Rourke B. Mitochondrial KATP channels in cell survival and death. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2005;39(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Garlid KD, Paucek P, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Sun X, Schindler PA. The mitochondrial KATP channel as a receptor for potassium channel openers. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(15):8796–8799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Clement JP, IV, Kunjilwar K, Gonzalez G, et al. Association and stoichiometry of KATP channel subunits. Neuron. 1997;18(5):827–838. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Melander A, Lebovitz HE, Faber OK. Sulfonylureas: why, which, and how? Diabetes Care. 1990;13(3):18–25. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.3.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Simard JM, Woo SK, Schwartzbauer GT, Gerzanich V. Sulfonylurea receptor 1 in central nervous system injury: a focused review. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2012;32:1699–1717. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dörschner H, Brekardin E, Uhde I, Schwanstecher C, Schwanstecher M. Stoichiometry of sulfonylurea-induced ATP-sensitive potassium channel closure. Molecular Pharmacology. 1999;55(6):1060–1066. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.6.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shyng S, Ferrigni T, Nichols CG. Regulation of KATP channel activity by diazoxide and MgADP: distinct functions of the two nucleotide binding folds of the sulfonylurea receptor. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110(6):643–654. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Petit P, Loubatieres-Mariani MM. Potassium channels of the insulin-secreting B cell. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 1992;6(3):123–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1992.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Koch Weser J. Diazoxide. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1976;294(23):1271–1274. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197606032942306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Warter A, Gillet B, Weryha A, Hagbe P, Simler M. Hypoglycemia due to insulinoma complicated with hepatic metastases. Excellent results after 20 months of treatment with diazoxide. Annales de Medecine Interne. 1970;121(11):927–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Inoue I, Nagase H, Kishi K, Higuti T. ATP-sensitive K+ channel in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Nature. 1991;352(6332):244–247. doi: 10.1038/352244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bajgar R, Seetharaman S, Kowaltowski AJ, Garlid KD, Paucek P. Identification and properties of a novel intracellular (mitochondrial) ATP-sensitive potassium channel in brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(36):33369–33374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lacza Z, Snipes JA, Kis B, Szabó C, Grover G, Busija DW. Investigation of the subunit composition and the pharmacology of the mitochondrial ATP-dependent K+ channel in the brain. Brain Research. 2003;994(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Suzuki M, Kotake K, Fujikura K, et al. Kir6.1: a possible subunit of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in mitochondria. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;241(3):693–697. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Garlid KD, Paucek P, Yarov-Yarovoy V, et al. Cardioprotective effect of diazoxide and its interaction with mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels: possible mechanism of cardioprotection. Circulation Research. 1997;81(6):1072–1082. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.6.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Iwai T, Tanonaka K, Koshimizu M, Takeo S. Preservation of mitochondrial function by diazoxide during sustained ischaemia in the rat heart. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;129(6):1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Iwai T, Tanonaka K, Motegi K, Inoue R, Kasahara S, Takeo S. Nicorandil preserves mitochondrial function during ischemia in perfused rat heart. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;446(1–3):119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01645-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Morin D, Assaly R, Paradis S, Berdeaux A. Inhibition of mitochondrial membrane permeability as a putative pharmacological target for cardioprotection. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;16(33):4382–4398. doi: 10.2174/092986709789712871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Peart JN, Gross GJ. Sarcolemmal and mitochondrial KATP channels and myocardial ischemic preconditioning. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2002;6(4):453–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brustovetsky T, Shalbuyeva N. Lack of manifestations of diazoxide/5-hydroxydecanoate-sensitive KATP channel in rat brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria. Journal of Physiology. 2005;568(1):47–59. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.091199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hansson MJ, Morota S, Teilum M, Mattiasson G, Uchino H, Elmér E. Increased potassium conductance of brain mitochondria induces resistance to permeability transition by enhancing matrix volume. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(1):741–750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.017731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hanley PJ, Dröse S, Brandt U, et al. 5-hydroxydecanoate is metabolised in mitochondria and creates a rate-limiting bottleneck for β-oxidation of fatty acids. Journal of Physiology. 2005;562(2):307–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.073932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Katoh H, Nishigaki N, Hayashi H. Diazoxide opens the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and alters Ca2+ transients in rat ventricular myocytes. Circulation. 2002;105(22):2666–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016831.41648.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Garlid KD, Halestrap AP. The mitochondrial KATP channel-Fact or fiction? Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2012;52(3):578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Garlid KD, Paucek P. Mitochondrial potassium transport: the K+ cycle. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2003;1606(1–3):23–41. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(03)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kowaltowski AJ, Seetharaman S, Paucek P, Garlid KD. Bioenergetic consequences of opening the ATP-sensitive K+ channel of heart mitochondria. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;280(2):H649–H657. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Huang Q, Guo Z, Yu Y, et al. Diazoxide inhibits aortic endothelial cell apoptosis in diabetic rats via activation of ERK. Acta Diabetologica. 2011:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00592-011-0288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Foster DB, Ho AS, Rucker J, et al. Mitochondrial ROMK channel is a molecular component of mitoKATP . Circulation Research. 2012;111(4):446–454. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.266445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hu H, Sato T, Seharaseyon J, et al. Pharmacological and histochemical distinctions between molecularly defined sarcolemmal KATP channels and native cardiac mitochondrial KATP channels. Molecular Pharmacology. 1999;55(6):1000–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Virgili N, Espinosa-Parrilla JF, Mancera P, et al. Oral administration of the KATP channel opener diazoxide ameliorates disease progression in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2011;8, article 149 doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Goodman Y, Mattson MP. K+ channel openers protect hippocampal neurons against oxidative injury and amyloid β-peptide toxicity. Brain Research. 1996;706(2):328–332. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Robin E, Simerabet M, Hassoun SM, et al. Postconditioning in focal cerebral ischemia: role of the mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channel. Brain Research. 2011;1375:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Roseborough G, Gao D, Chen L, et al. The mitochondrial K-ATP channel opener, diazoxide, prevents ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rabbit spinal cord. American Journal of Pathology. 2006;168(5):1443–1451. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhou F, Yao H, Wu J, Ding J, Sun T, Hu G. Opening of microglial KATP channels inhibits rotenone-induced neuroinflammation. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2008;12(5A):1559–1570. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mastrangelo MA, Bowers WJ. Detailed immunohistochemical characterization of temporal and spatial progression of Alzheimer’s disease-related pathologies in male triple-transgenic mice. BMC Neuroscience. 2008;9, article 81 doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Liu D, Pitta M, Lee J, et al. The KATP channel activator diazoxide ameliorates amyloid-β and Tau pathologies and improves memory in the 3xTgAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;22(2):443–457. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ma G, Fu Q, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of Aβ1-42 on the subunits of KATP expression in cultured primary rat basal forebrain neurons. Neurochemical Research. 2008;33(7):1419–1424. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Caldeira GL, Ferreira IL, Rego AC. Impaired transcription in Alzheimer’s disease: key role in mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2013;34:115–131. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sadowski M, Pankiewicz J, Scholtzova H, et al. Amyloid-β deposition is associated with decreased hippocampal glucose metabolism and spatial memory impairment in APP/PS1 mice. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2004;63(5):418–428. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rodríguez MJ, Martínez-Sánchez M, Bernal F, Mahy N. Heterogeneity between hippocampal and septal astroglia as a contributing factor to differential in vivo AMPA excitotoxicity. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2004;77(3):344–353. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rodríguez MJ, Prats A, Malpesa Y, et al. Pattern of injury with a graded excitotoxic insult and ensuing chronic medial septal damage in the rat brain. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2009;26(10):1823–1834. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Holmuhamedov EL, Wang L, Terzic A. ATP-sensitive K+ channel openers prevent Ca2+ overload in rat cardiac mitochondria. Journal of Physiology. 1999;519(2):347–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0347m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wang Y, Hirai K, Ashraf M. Activation of mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel for cardiac protection against ischemic injury is dependent on protein kinase C activity. Circulation Research. 1999;85(8):731–741. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.8.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]