Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive impairment and multiple pathological lesions. At the molecular level, AD is characterized by overt amyloid β (Aβ) production and tau hyper-phosphorylation. Hence, pharmacological agents that can attenuate Aβ accumulation and tau hyper-phosphorylation have potential promise for treatment of AD. Rapamycin, an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), is believed to be one of such pharmacological agents. It is neuroprotective in neurodegenerative diseases and its primary action is thought to be via enhancement of autophagy, a biological process that not only facilitates the clearance of mutant proteins but also significantly reduces the build-up of toxic protein aggregates such as Aβ. Since rapamycin enhancement of autophagy has been associated with abrogation of AD pathological processes such as clearance of Aβ and neurofibrillary tangles (NTFs) as well as reduction of tau hyper-phosphorylation and improvement of cognition, rapamycin is emerging as a potential therapeutic compound for AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, autophagy, mTOR, neuroinflammation, rapamycin, oxidative stress, synaptic impairment

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease of aging [1, 2]. Patients with AD suffer from progressive functional impairment, the loss of independence, emotional distress, and behavioral symptoms [3]. AD is pathologically characterized by the presence of cerebral atrophy, extracellular amyloid plaques, and intra-neuronal neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [4, 5]. Beta-amyloid peptide (Aβ) generation and deposition is recognized as a major contributor in the triggering of AD. NFTs, the insoluble twisted fibers found intracellularly in the AD brain, are also recognized as another important pathological manifestation of the disease.

Rapamycin, a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for preventing the immune system from attacking transplanted organs, may fight AD [6]. In this review, we focus on the roles of rapamycin in rescuing the pathology of amyloid plaques and NFTs, which are the two main factors in AD that can impair synaptic structure and function as well as neural plasticity and cognition. We also present evidence that rapamycin exerts its neuroprotective effects through autophagy enhancement. In addition, whether rapamycin could be an effective therapeutic compound for preventing or reversing AD pathology is also discussed.

2. Rapamycin

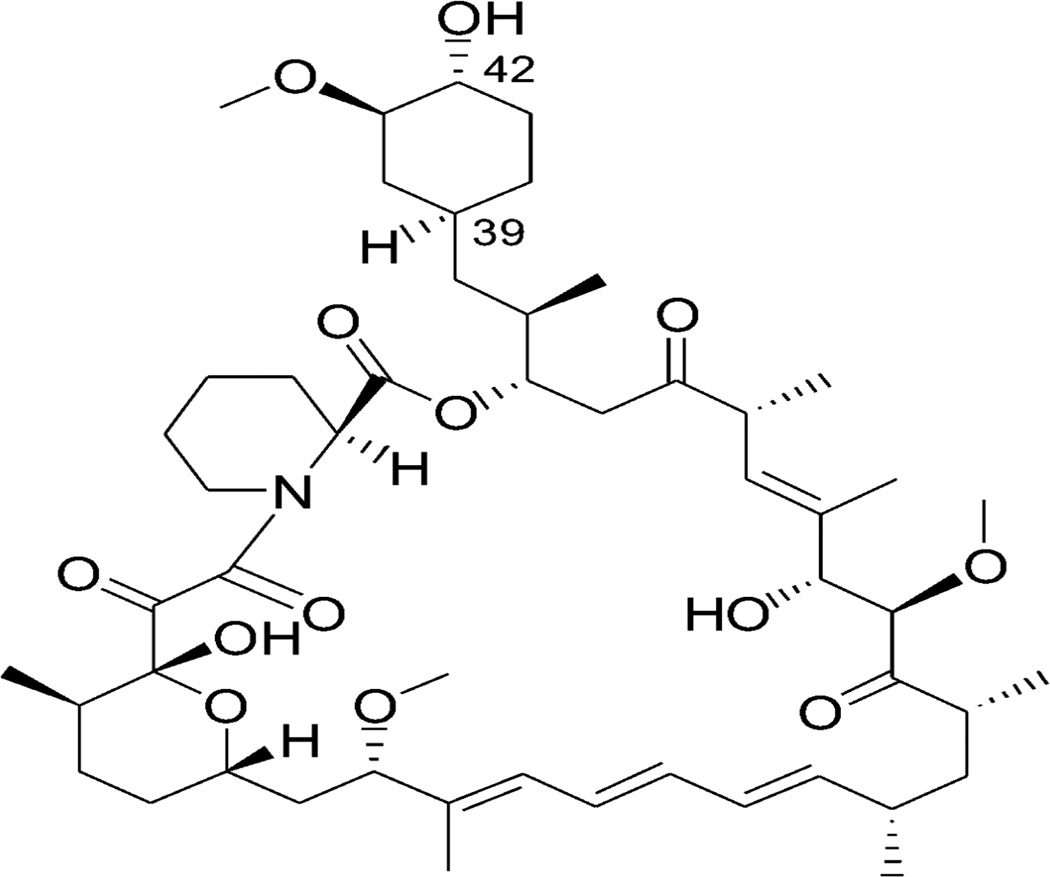

Rapamycin (Fig. 1), first isolated from a strain of Streptomyces hygroscopicus indigenous to Easter Island, is a member of a family of macrolide immunosuppressants used to prevent rejections following organ transplantation via the inhibition of T and B cell proliferation [7–9]. Rapamycin inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway via direct binding of mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1) that is a nutrient-sensitive kinase [10, 11]. Therefore, rapamycin is involved in many cellular functions, such as cell growth, proliferation, protein synthesis, and autophagy. Studies have shown that rapamycin can extend the lifespan of organisms and slow the progression of aging [12, 13]. For example, rapamycin was shown to extend lifespan and retard aging in yeast [14] and mouse [15], respectively. Moreover, as rapamycin has anti-proliferative effects [16, 17], it may benefit patients with cancer [18, 19], adipogenesis [20, 21], diabetes [22, 23], tuberous sclerosis [24, 25], cardiovascular diseases [26–29], and neurological disorders [30, 31]. In the brain, the most striking effect of rapamycin is its neuroprotective effects, making it a potential therapeutic pharmacological compound to curb neurodegenerative disorders [32] such as Alzheimer's disease [6, 12, 33, 34], Parkinson's disease [35, 36], and Huntington's disease [37, 38]. The underlying neuroprotective mechanisms of rapamycin are thought to be related to its effects on autophagy enhancement [39–41].

Fig. 1.

The chemical structure of rapamycin.

3. Autophagy

Autophagy is a lysosome-mediated, self-digesting degradation mechanism that involves the removal of damaged organelles and misfolded or nonfunctional proteins [42, 43]. Autophagy is essential for cell growth, survival, differentiation, development as well as protein homeostasis, and maintains a balance between the synthesis, degradation, and subsequent recycling of cellular products [44, 45]. Autophagy plays an important role in a variety of pathologies such as cancer [46, 47] and neurodegeneration [6]. Numerous studies have shown that the process of autophagy is negatively regulated by the activation of mTOR because mTORC1 and Atg1/ULK complexes can coordinately regulate autophagy in response to pathophysiological stress [48–51].

4. Rapamycin and neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s disease

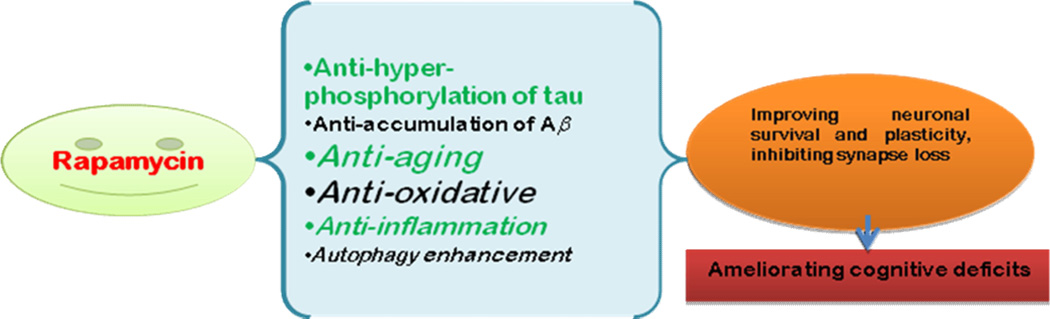

Increasing evidence indicates that rapamycin is an effective inhibitor of the neurodegeneration that occurs in AD. Evidence includes: 1) rapamycin inhibition of mTOR improves AD-linked cognitive deficits [12, 52]; 2) rapamycin enhancement of autophagy reduces Aβ accumulation [6, 34]; and 3) rapamycin enhancement of autophagy attenuates tau hyper-phosphorylation [53, 54]. Fig. 2 summarizes the potential protective mechanisms of rapamycin in AD.

Figure 2.

Scheme showing potential mechanisms by which rapamycin ameliorates Alzheimer’s-like cognitive deficits. The mechanism primarily includes: anti-aging effects, anti-oxidative stress and anti- neuroinflammation properties, enhancement of autophagy, and inhibition of both Aβ accumulation and tau hyper-phosphorylation.

4.1. Rapamycin ameliorates the cognitive deficits in AD

The clinical manifestations of patients with AD usually include insidiously progressive memory loss, language disorders, and cognitive dysfunction in both visuospatial skills and executive functions. The cognitive deficits may be associated with slowly progressive behavioral changes. At later stages of AD, the patients develop memory and mobility loss, exhibits unusual behavior, and have problems with communication and continence. As studies have revealed in mouse models of AD that rapamycin attenuates the accumulation of Aβ and hyper-phosphorylated tau, decreases neuroinflammation, improves synaptic plasticity, and helps to ameliorate the loss of cognitive function [33, 52, 55], it is possible that in humans rapamycin may have similar effects.

4.1.1. Effects of rapamycin on aging and AD

It is well accepted that aging is the greatest risk factor for AD. It has been demonstrated that, in mice, the chronic inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin not only enhances learning and memory but also modulates their behavior throughout their lifespan [56]. For example, the performance of 18-month-old mice on a task measuring their spatial learning and memory is significantly improved when treated with rapamycin, an effect that has been determined to be mediated by IL-1β and NMDA signaling [57]. Thus, rapamycin could be an effective cognition-improving agent in aging and AD.

4.1.2. Effects of rapamycin on oxidative stress and neuroinflammation

Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation have been reported to promote cognitive impairment in AD as they can facilitate Aβ generation and NFTs formation [58, 59] that in turn contribute to the progressive cognitive deficits of AD [52, 60, 61]. Many studies have demonstrated that rapamycin improves learning and memory through the inhibition of Aβ and tau accumulation by interfering with several signaling cascades [34, 62, 63] that involve interactions between oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [58, 64]. Therefore, rapamycin is thought to exert its neuroprotective actions via its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capabilities [35, 65–67], which may also be associated with its ability to ameliorate cognition impairment.

4.1.3. Effects of rapamycin on synaptic impairment

Synaptic impairment is the basis of memory loss in AD, and synapse loss is an early feature of AD [68, 69]. Extensive data have demonstrated that the memory impairment observed in AD is closely associated with decreased hippocampal synaptic plasticity. As there is also a positive correlation between the extent of synaptic loss and the severity of dementia [68, 70], rapamycin, via inhibiting dysregulation of the mTOR pathway that leads to loss of synaptic plasticity in AD [71], can exhibit favorable effects on neuronal survival and plasticity, and facilitate memory improvement. Studies have indicated that rapamycin not only directly renovates long-term synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus [72], but also improves synaptic function by limiting Aβ accumulation and tau hyper-phosphorylation that otherwise can impair synaptic structure, function and plasticity, as well as memory [73].

5. Rapamycin reduces the level of Aβ and enhances Aβ clearance

Under normal physiological conditions, Aβ that is generated and aggregated can be degraded by the autophagy-lysosome system [74–76]. However, when function of the autophagy-lysosome system is impaired, Aβ could be accumulated and there could also be a failure in removing it [77, 78]. In this sense, rapamycin protects against neurodegeneration because it can enhance autophagy that then facilitates the clearance of Aβ aggregates [79, 80].

Specifically, it has been shown that rapamycin decreases Aβ- related pathologies [12, 34, 81], induces neuronal survival and plasticity, and hence can rescue cognitive deficit. With respect to the underlying mechanisms, it has been reported that in PC12 cells rapamycin activates the autophagy pathway, upregulates Aβ42-induced Beclin-1 expression that promotes cell survival [82]. When Beclin-1 is down-regulated by the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine, cell death is promoted [82]. Such results suggest that activation of Beclin-1-dependent autophagy can prevent neuronal cell death and that inhibition of Beclin-1-dependent autophagy can promote cell death [82]. As autophagy plays an important role in Aβ generation by modulating metabolism of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and controlling the expression of β- and γ-secretases [83–87], rapamycin enhancement of autophagy can thus modulate APP metabolism, lower β- and γ-secretase expression, and result in decrease in Aβ levels. Additionally, similar to rapamycin’s effect on cognition improvement, it is likely that rapamycin lowers Aβ levels also through its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which have been characterized by rapamycin’s impact on several redox signaling pathways, such as PI3K/Akt [63, 88, 89], mTOR [88–90], CaMKKβ/AMPK [91], and insulin/IGF-1 signaling [92, 93].

6. Rapamycin restrains tau hyperphosphorylation

Increasing evidence indicates that the activation of mTOR signaling is involved in tau phosphorylation and degradation [94, 95]. Hence, suppressing mTOR signaling with rapamycin can enhance autophagy that further ameliorates the tau pathology and improves cognitive deficits [81]. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway regulates tau phosphorylation at many sites by controlling the GSK-3-dependent phosphorylation of tau [96–98], and excessive activation of mTOR can also induce the occurrence of tau-phosphorylated proteins in the hippocampal tissue of rats with type 2 diabetes and AD [99]. It should be noted that tau protein expression is also associated with levels of mTOR and its downstream targets, such as the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1), eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2), and eEF2 kinase [100]. Interestingly, similar to rapamycin, phosphatidic acid can also activate the mTOR pathway, thereby modulating tau phosphorylation and oxidative stress [101]. Additionally, it is also known that rapamycin suppresses the translation of both tau and collapsing response mediator protein 2 (CRMP2), which play important roles in axon formation from neurites through their interactions with microtubules [102, 103]. These results demonstrate that rapamycin can exert a variety of effects on tau via different mechanisms.

While enhancement of autophagy by rapamycin promotes the clearance of the hyper-phosphorylated tau [6], rapamycin may also attenuate the process of tau hyper-phosphorylation. For example, it has been reported that rapamycin could decrease tau phosphorylation at Serine-214 via the regulation of cAMP-dependent kinase, leading to less build-up of hyper-phosphorylated tau [62]. Therefore, by controlling the autophagy pathway, rapamycin can regulate both tau phosphorylation and the build-up of hyper-phosphorylated tau.

7. Discussions and perspectives

It is well established that mTOR plays a central role in the maintenance of protein homeostasis [42, 43], which deteriorates during aging and in age-related neurodegeneration. Therefore, not surprisingly, mTOR could be involved in lifespan regulation and in age-related pathogenesis [13, 16, 57, 104, 105]. By restraining the activity of mTOR signaling, inhibiting mTOR protein biosynthesis, and enhancing autophagy, rapamycin can thus protect against Aβ toxicity and tau pathology, promote neuronal survival and plasticity, thereby leading to learning rescue and memory enhancement. Therefore, rapamycin targeting of mTOR could be a potential approach for treating AD.

Although rapamycin exhibits beneficial effects in AD as described above, several studies have also shown that rapamycin could cause detrimental effects. For example, it was reported that rapamycin could exacerbate the neurotoxicity of Aβ peptides [106], and could also accelerate Aβ generation by decreasing the activation of a disintegrin and metallopeptidase domain-10 (ADAM-10), which is an important target of α-secretase [107]. However, the discrepancy between these beneficial and deleterious effects of rapamycin remains unknown at this point.

Finally, whether the results obtained in mice and tissue cultures can also be observed in humans remains unknown. As an immunosuppressant, rapamycin treatment of AD patients over a prolonged period might be harmful to the immune system, a potential adverse effect that needs to be investigated. Moreover, further clinical studies also remain to be conducted to determine whether rapamycin could indeed be a successful therapeutic compound for the treatment of AD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by the Provincial Nature Science Foundation of Anhui Province (1308085MH158 to Z.C.) and by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institutes of Health (R01NS079792 to L.J.Y.). The content in this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Foley JA, et al. Dual-task performance in Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, and normal ageing. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;26:340–348. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindeboom J, Weinstein H. Neuropsychology of cognitive ageing, minimal cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular cognitive impairment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;490:83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien JT, et al. Temporal lobe magnetic resonance imaging can differentiate Alzheimer's disease from normal ageing, depression, vascular dementia and other causes of cognitive impairment. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1267–1275. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giaccone G, et al. beta PP and Tau interaction. A possible link between amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:79–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goedert M, et al. Neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid deposits in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1991;1:441–447. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(91)90067-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai Z, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin: a valid therapeutic target through the autophagy pathway for Alzheimer's disease? J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:1105–1118. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanna AK. Mechanism of the combination immunosuppressive effects of rapamycin with either cyclosporine or tacrolimus. Transplantation. 2000;70:690–694. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200008270-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wicker LS, et al. Suppression of B cell activation by cyclosporin A, FK506 and rapamycin. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2277–2283. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohacsi PJ, Morris RE. Brief treatment with rapamycin in vivo increases responsiveness to alloantigens measured by the mixed lymphocyte response. Immunol Lett. 1992;34:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90224-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schriever SC, et al. Cellular signaling of amino acids towards mTORC1 activation in impaired human leucine catabolism. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pous C, Codogno P. Lysosome positioning coordinates mTORC1 activity and autophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:342–344. doi: 10.1038/ncb0411-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos RX, et al. Effects of rapamycin and TOR on aging and memory: implications for Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2011;117:927–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13].Komarova EA, et al. Rapamycin extends lifespan and delays tumorigenesis in heterozygous p53+/- mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:709–714. doi: 10.18632/aging.100498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powers RW, et al. Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling. Genes Dev. 2006;20:174–184. doi: 10.1101/gad.1381406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison DE, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anisimov VN, et al. Rapamycin extends maximal lifespan in cancer-prone mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2092–2097. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anisimov VN, et al. Rapamycin increases lifespan and inhibits spontaneous tumorigenesis in inbred female mice. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:4230–4236. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.24.18486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heuer M, et al. Tumor growth effects of rapamycin on human biliary tract cancer cells. Eur J Med Res. 2012;17:20. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-17-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, et al. Rapamycin inhibits FBXW7 loss-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like characteristics in colorectal cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.077. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JE, Chen J. regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activity by mammalian target of rapamycin and amino acids in adipogenesis. Diabetes. 2004;53:2748–2756. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Chaar D, et al. Inhibition of insulin signaling and adipogenesis by rapamycin: effect on phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase vs eIF4E-BP1. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:191–198. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie J, Herbert TP. The role of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in the regulation of pancreatic beta-cell mass: implications in the development of type-2 diabetes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:1289–1304. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0874-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long SA, et al. Rapamycin/IL-2 combination therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes augments Tregs yet transiently impairs beta-cell function. Diabetes. 2012;61:2340–2348. doi: 10.2337/db12-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosado C, et al. Tuberous sclerosis associated with polycystic kidney disease: effects of rapamycin after renal transplantation. Case Rep Transplant. 2013;2013:397087. doi: 10.1155/2013/397087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wataya-Kaneda M, et al. A novel application of topical rapamycin formulation, an inhibitor of mTOR, for patients with hypomelanotic macules in tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:138–139. doi: 10.1001/archderm.148.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selman C, Partridge L. A double whammy for aging? Rapamycin extends lifespan and inhibits cancer in inbred female mice. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:17–18. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.1.18736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comas M, et al. New nanoformulation of rapamycin Rapatar extends lifespan in homozygous p53-/- mice by delaying carcinogenesis. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:715–722. doi: 10.18632/aging.100496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in diabetic cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;11:45. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ru W, et al. A role of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in glutamate-induced down-regulation of tuberous sclerosis complex proteins 2 (TSC2) J Mol Neurosci. 2012;47:340–345. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9753-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsang CK, et al. Targeting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) for health and diseases. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chong ZZ, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin: hitting the bull's-eye for neurological disorders. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3:374–391. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.6.14787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li S. The possible cellular mechanism for extending lifespan of mice with rapamycin. Biol Proced Online. 2009;11:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s12575-009-9015-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierce A, et al. Over-expression of heat shock factor 1 phenocopies the effect of chronic inhibition of TOR by rapamycin and is sufficient to ameliorate Alzheimer's-like deficits in mice modeling the disease. J Neurochem. 2013;124:880–893. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spilman P, et al. Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin abolishes cognitive deficits and reduces amyloid-beta levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang J, et al. Rapamycin protects the mitochondria against oxidative stress and apoptosis in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31:825–832. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malagelada C, et al. Rapamycin protects against neuron death in in vitro and in vivo models of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1166–1175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3944-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarkar S, et al. A rational mechanism for combination treatment of Huntington's disease using lithium and rapamycin. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:170–178. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Floto RA, et al. Small molecule enhancers of rapamycin-induced TOR inhibition promote autophagy, reduce toxicity in Huntington's disease models and enhance killing of mycobacteria by macrophages. Autophagy. 2007;3:620–622. doi: 10.4161/auto.4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chong ZZ, et al. Shedding new light on neurodegenerative diseases through the mammalian target of rapamycin. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;99:128–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graziotto JJ, et al. Rapamycin activates autophagy in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: implications for normal aging and age-dependent neurodegenerative disorders. Autophagy. 2012;8:147–151. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.1.18331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendelsohn AR, Larrick JW. Rapamycin as an antiaging therapeutic?: targeting mammalian target of rapamycin to treat Hutchinson-Gilford progeria and neurodegenerative diseases. Rejuvenation Res. 2011;14:437–441. doi: 10.1089/rej.2011.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naves T, et al. Autophagic subpopulation sorting by sedimentation field-flow fractionation. Anal Chem. 2012;84:8748–8755. doi: 10.1021/ac302032v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahn J, Kim J. Nutritional status and cardiac autophagy. Diabetes Metab J. 2013;37:30–35. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2013.37.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sridhar S, et al. Autophagy and disease: always two sides to a problem. J Pathol. 2012;226:255–273. doi: 10.1002/path.3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavallard VJ, et al. Autophagy, signaling and obesity. Pharmacol Res. 2012;66:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trocoli A, Djavaheri-Mergny M. The complex interplay between autophagy and NF-kappaB signaling pathways in cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:629–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen HY, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer prevention. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:973–983. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hands SL, et al. mTOR's role in ageing: protein synthesis or autophagy? Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:586–597. doi: 10.18632/aging.100070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ravikumar B, Rubinsztein DC. Role of autophagy in the clearance of mutant huntingtin: a step towards therapy? Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alers S, et al. Role of AMPK-mTOR-Ulk1/2 in the regulation of autophagy: cross talk, shortcuts, and feedbacks. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:2–11. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06159-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung CH, et al. mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Majumder S, et al. Inducing autophagy by rapamycin before, but not after, the formation of plaques and tangles ameliorates cognitive deficits. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caccamo A, et al. mTOR regulates tau phosphorylation and degradation: implications for Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies. Aging Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1111/acel.12057. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y, et al. Rapamycin decreases tau phosphorylation at Ser214 through regulation of cAMP-dependent kinase. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Avrahami L, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 ameliorates beta-amyloid pathology and restores lysosomal acidification and mammalian target of rapamycin activity in the Alzheimer disease mouse model: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1295–1306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.409250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Halloran J, et al. Chronic inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin by rapamycin modulates cognitive and non-cognitive components of behavior throughout lifespan in mice. Neuroscience. 2012;223:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Majumder S, et al. Lifelong rapamycin administration ameliorates age-dependent cognitive deficits by reducing IL-1beta and enhancing NMDA signaling. Aging Cell. 2012;11:326–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agostinho P, et al. Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2766–2778. doi: 10.2174/138161210793176572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cai Z, Yan LJ, Ratka A. Telomere shortening and Alzheimer's disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2013;15:25–48. doi: 10.1007/s12017-012-8207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rasool S, et al. Vaccination with a non-human random sequence amyloid oligomer mimic results in improved cognitive function and reduced plaque deposition and micro hemorrhage in Tg2576 mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee KW, et al. Progressive cognitive impairment and anxiety induction in the absence of plaque deposition in C57BL/6 inbred mice expressing transgenic amyloid precursor protein. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:572–580. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Y, et al. Rapamycin decreases tau phosphorylation at Ser214 through regulation of cAMP-dependent kinase. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maiese K, et al. Oxidant Stress and Signal Transduction in the Nervous System with the PI 3-K, Akt, and mTOR Cascade. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:13830–13866. doi: 10.3390/ijms131113830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Galimberti D, Scarpini E. Inflammation and oxidative damage in Alzheimer's disease: friend or foe? Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2011;3:252–266. doi: 10.2741/s149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marobbio CM, et al. Rapamycin reduces oxidative stress in frataxin-deficient yeast cells. Mitochondrion. 2012;12:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen HC, et al. Multifaceted effects of rapamycin on functional recovery after spinal cord injury in rats through autophagy promotion, anti-inflammation, and neuroprotection. J Surg Res. 2013;179:e203–e210. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen WQ, et al. Oral rapamycin attenuates inflammation and enhances stability of atherosclerotic plaques in rabbits independent of serum lipid levels. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:941–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shankar GM, Walsh DM. Alzheimer's disease: synaptic dysfunction and Abeta. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:48. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oddo S, et al. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kokubo H, et al. Soluble Abeta oligomers ultrastructurally localize to cell processes and might be related to synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease brain. Brain Res. 2005;1031:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma T, et al. Dysregulation of the mTOR pathway mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2010;5(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tang SJ, et al. A rapamycin-sensitive signaling pathway contributes to long-term synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:467–472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012605299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shankar GM, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steele JW, Gandy S. Apomorphine and Alzheimer Abeta: roles for regulated alpha cleavage, autophagy, and antioxidation? Ann Neurol. 2011;69:221–225. doi: 10.1002/ana.22359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tian Y, Bustos V, Flajolet M, Greengard P. A small-molecule enhancer of autophagy decreases levels of Abeta and APP-CTF via Atg5-dependent autophagy pathway. FASEB J. 2011;25(6):1934–1942. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-175158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee JA, Gao FB. Regulation of Abeta pathology by beclin 1: a protective role for autophagy? J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2015–2018. doi: 10.1172/JCI35662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nixon RA. Autophagy, amyloidogenesis and Alzheimer disease. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4081–4091. doi: 10.1242/jcs.019265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hung SY, et al. Autophagy protects neuron from Abeta-induced cytotoxicity. Autophagy. 2009;5:502–510. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.4.8096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bove J, et al. Fighting neurodegeneration with rapamycin: mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:437–452. doi: 10.1038/nrn3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ravikumar B, et al. Rapamycin pre-treatment protects against apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1209–1216. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Caccamo A, et al. Molecular interplay between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), amyloid-beta, and Tau: effects on cognitive impairments. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13107–13120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xue Z, et al. Upexpression of Beclin-1-Dependent Autophagy Protects Against Beta-amyloid-Induced Cell Injury in PC12 Cells. J Mol Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-9974-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang J, et al. Autophagosomes accumulation is associated with beta-amyloid deposits and secondary damage in the thalamus after focal cortical infarction in hypertensive rats. J Neurochem. 2012;120:564–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Son SM, et al. Accumulation of autophagosomes contributes to enhanced amyloidogenic APP processing under insulin-resistant conditions. Autophagy. 2012;8:1842–1844. doi: 10.4161/auto.21861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhou F, et al. APP and APLP1 are degraded through autophagy in response to proteasome inhibition in neuronal cells. Protein Cell. 2011;2:377–383. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1047-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jaeger PA, et al. Regulation of amyloid precursor protein processing by the Beclin 1 complex. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yu WH, et al. Autophagic vacuoles are enriched in amyloid precursor protein-secretase activities: implications for beta-amyloid peptide over-production and localization in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2531–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nemoto T, et al. Insulin-induced neurite-like process outgrowth: acceleration of tau protein synthesis via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase~mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Neurochem Int. 2011;59:880–888. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bhaskar K, et al. The PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway regulates Abeta oligomer induced neuronal cell cycle events. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chong ZZ, et al. A Critical Kinase Cascade in Neurological Disorders: PI 3-K, Akt, and mTOR. Future Neurol. 2012;7:733–748. doi: 10.2217/fnl.12.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vingtdeux V, et al. Novel synthetic small-molecule activators of AMPK as enhancers of autophagy and amyloid-beta peptide degradation. FASEB J. 2011;25:219–231. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-167361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Marwarha G, et al. Molecular interplay between leptin, insulin-like growth factor-1, and beta-amyloid in organotypic slices from rabbit hippocampus. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.O'Neill C, et al. Insulin and IGF-1 signalling: longevity, protein homoeostasis and Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:721–727. doi: 10.1042/BST20120080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sarnat H, et al. Hemimegalencephaly: foetal tauopathy with mTOR hyperactivation and neuronal lipidosis. Folia Neuropathol. 2012;50:330–345. doi: 10.5114/fn.2012.32363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.An WL, et al. Up-regulation of phosphorylated/activated p70 S6 kinase and its relationship to neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:591–607. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63687-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Meske V, et al. Coupling of mammalian target of rapamycin with phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathway regulates protein phosphatase 2A- and glycogen synthase kinase-3-dependent phosphorylation of Tau. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:100–109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Neill CO. PI3-kinase/Akt/mTOR signalling: Impaired on/off switches in aging, cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease. Exp Gerontol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.025. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nemoto T, et al. Homologous posttranscriptional regulation of insulin-like growth factor-I receptor level via glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and mammalian target of rapamycin in adrenal chromaffin cells: effect on tau phosphorylation. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:1097–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ma YQ, Wu DK, Liu JK. mTOR and tau phosphorylated proteins in the hippocampal tissue of rats with type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's disease. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7:623–627. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li X, et al. Levels of mTOR and its downstream targets 4E-BP1, eEF2, and eEF2 kinase in relationships with tau in Alzheimer's disease brain. FEBS J. 2005;272:4211–4220. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Taga M, et al. Modulation of oxidative stress and tau phosphorylation by the mTOR activator phosphatidic acid in SH-SY5Y cells. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1801–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Morita T, Sobue K. Specification of neuronal polarity regulated by local translation of CRMP2 and Tau via the mTOR-p70S6K pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27734–27745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kickstein E, et al. Biguanide metformin acts on tau phosphorylation via mTOR/protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21830–21835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912793107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Johnson SC, et al. mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease. Nature. 2013;493:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature11861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Salminen A, Kaarniranta K. Regulation of the aging process by autophagy. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lafay-Chebassier C, et al. The immunosuppressant rapamycin exacerbates neurotoxicity of Abeta peptide. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:1323–1334. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang S, et al. Rapamycin promotes beta-amyloid production via ADAM-10 inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]