Abstract

The G0/G1 switch gene 2 (G0S2) was originally identified in blood mononuclear cells following induced cell cycle progression. Translation of G0S2 results in a small basic protein of 103 amino acids in size. It was initially believed that G0S2 mediates re-entry of cells from the G0 to G1 phase of the cell cycle. Recent studies have begun to reveal the functional aspects of G0S2 and its protein product in various cellular settings. To date the best-known function of G0S2 is its direct inhibitory capacity on the rate-limiting lipolytic enzyme adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL). Other studies have illustrated key features of G0S2 including sub-cellular localization, expression profiles and regulation, and possible functions in cellular proliferation and differentiation. In this review we present the current knowledge base regarding all facets of G0S2 and pose a variety of questions and hypotheses pertaining to future research directions.

Keywords: G0/G1 switch gene 2, G0S2, lipolysis, adipocyte metabolism, cell proliferation, differentiation, quiescence/growth arrest, cell cycle, PPARs, cancer metabolism, apoptosis

1. Introduction

The G0/G1 switch gene 2 (G0S2) was discovered in the early 1990s by Russell and Forsdyke in cultured mononuclear cells during the drug-induced cell cycle transition from G0 to G1 phase [1] [2]. G0S2 only exists in vertebrates, and has no homologs in lower organisms such as Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila. In both mouse and human, G0S2 is located on chromosome 1 of the genome and encodes a small basic protein of 103 amino acids in size. The G0S2 protein is highly conserved between species; there is 78% identity between mouse and human isoforms. No striking features are present in the protein structure that would hint at an immediate discernable function. According to protein secondary structure prediction, the G0S2 protein contains two α-helices separated by a hydrophobic sequence with the potential to generate turns and assume a β-sheet conformation. In addition, there are several putative phosphorylation sites for protein kinase C (PKC) and casein kinase II within the sequence of G0S2, though no evidence has been obtained that G0S2 is actually a phosphoprotein [1].

The expression of G0S2 has been profiled in various human and mouse cell types. As with many highly regulated and conserved genes present throughout the genome, G0S2 features a CpG-rich island that potentially allows for germ-line expression [1]. The promoter region of G0S2 contains potential binding sites for the transcription factors AP1, AP2, AP3 and Nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT), as well as a number of sequence motifs that can respond to transcriptional activation induced by specific agents including lectin, retinoic acid (RA), agonists for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), glucose and insulin [1, 3–8]. Results from a limited number of studies have implied that G0S2 is a multifaceted protein involved in proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation, metabolism, and carcinogenesis. In particular, recent studies have provided compelling evidence that G0S2 is abundantly expressed in metabolically active tissues such as fat and liver, and acts as a molecular brake on triglyceride (TG) catabolism [8]. In this review, we have summarized the existing evidence on G0S2 expression, and functional aspects to which G0S2 has been thus far associated.

2. G0S2 and proliferation of hematopoietic cells

A transient increase in G0S2 mRNA, peaking between 1–2 h, was observed in human mononuclear hematopoietic cells in response to proliferative activation by lectin and a protein synthesis inhibitor [1]. The lectin-induced expression of G0S2 was inhibitable by the immunosuppressant antibiotic cyclosporine A [9]. Cyclosporine A antagonizes the function of the calcium-dependent phosphatase calcineurin, which is required for activation of target genes of NFAT [10]. Consequently, it was postulated that G0S2 expression is required to commit cells to enter the G1 phase of the cell cycle [1], and early inhibition of G0S2 expression by cyclosporine A may be important in achieving immunosuppression [9]. However, recent evidence obtained by Yamada et al. from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) suggests that G0S2 acts to inhibit cell proliferation and assists to maintain stem cell in a quiescent state [11]. While G0S2 expression promoted quiescence in HSCs, silencing of endogenous G0S2 expression in bone marrow cells increased blood chimerism upon transplantation as well as HSC division. Moreover, G0S2 was found to directly interact with nucleolin, a multifunctional protein that regulates many aspects of DNA and RNA metabolism, protein synthesis and cell mass, and nucleocytoplasmic transport of newly synthesized pre-RNAs [11]. Thus, it was proposed that the cytosolic retention of nucleolin mediated by G0S2 contributes to the decreased proliferation of HSCs [11]. Furthermore, a separate study by Kobayashi et al. showed that G0S2 expression was remarkably augmented in peripheral mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from patients with the systemic autoimmune disease vasculitis [12]. Transgenic expression of G0S2 in mice under the control of a global β-actin promoter resulted in elevated serum levels of anti-nuclear antibody and anti-double strand DNA antibody, two autoimmunity-related markers. However, increased G0S2 expression does not appear to be sufficient for autoimmunity induction, since these transgenic mice displayed no obvious vasculitis-related phenotypes [12]. Most recently, upregulated G0S2 message expression in PBMCs was also reported in patients from an unfavorable group of acute graft-vs-host disease (aGVHD) after HSC transplantation [13].

3. G0S2 in cancer development

Several studies have linked the epigenetic regulation of G0S2 expression to carcinogenesis. The G0S2 gene was reported to be hypermethylated in several human cancer cell lines as well as in squamous head, neck and lung cancers [14–16]. A causal relationship between DNA methylation and suppression of G0S2 expression was established by the treatment of LC-1/sq squamous lung cancer cells with DNA demethylating agent 5-Aza-2′-deoxcytidine [15]. Moreover, G0S2 was found to localize different subcellular membrane structures including endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria [4, 17]. A study by Welch et al. showed that G0S2 interacts with Bcl-2 at the mitochondria and thereby modulates its anti-apoptotic activity in human cancer cells [17]. Although G0S2 does not possess the traditional Bcl-2 homology domain, its ability to interact with Bcl-2 effectively disrupts the formation of the anti-apoptotic heterodimeric complex of Bcl-2/Bax [17].

Combined with its growth arrest-associated expression in preadipocyte cells and epigenetic silencing in cancer, the identification of the proapoptotic activity of G0S2 raises the possibility that G0S2 is a tumor suppressor gene. The fact that knockdown of G0S2 promoted oncogene-induced transformation supports this idea [17]. However, there were no observable effects on growth arrest or apoptosis when G0S2 was overexpressed in LC-1/sq cancer cells [15]. If anything, slight increases in cell proliferation were observed in response to increased G0S2 levels, which was believed to be more likely a result of carcinogenesis rather than a primary cause [15]. Therefore, further investigation is needed to understand the functional involvement of G0S2 in carcinogenesis.

In addition, the G0S2 was also found to be a target of all-trans retinoic acid (RA) in human acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) cells [5]. RA treatment is a model of effective therapy based on inducing terminal differentiation of APL cells. Both mRNA and protein of G0S2 were rapidly induced in cultured human APL cells and in APL transgenic mice treated with RA. Moreover, the G0S2 promoter contains RA response element (RARE) half-sites, and mutations within RARE blocked all RA induced transcriptional activation [5]. While the evidence supporting G0S2’s ability to act as a RA target gene is convincing, the functional role of G0S2 in the RA response of APL remains undefined.

4. G0S2 as a regulator of lipid metabolism

4.1. Adipose lipolysis

In a search for novel genes involved in mesenchymal lineage differentiation, Bachner and colleagues identified G0S2 as an adipose-specific factor whose expression can be upregulated by bone morphogenetic protein 2 (Bmp-2) in mouse embryos [18]. The G0S2 expression is highly restricted to BAT and WAT at embryonic day 18.5 as revealed by in situ hybridization analysis. Later studies confirmed that G0S2 mRNA is also most highly expressed in adipose tissue of adult animals [4, 19, 20] and humans [21]. In cultured human Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome (SGBS) and mouse 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell lines, both G0S2 mRNA and protein steadily increase as the cells enter the growth arrest stage preceding the terminal differentiation [4, 8, 21]. However, despite its postulated role as a cell cycle regulator, whether G0S2 plays any active role in the cell cycle withdrawal during adipogenic differentiation remains unclear.

The G0S2 promoter encompasses a potential PPAR-responsive element (PPRE), and G0S2 was shown to be a direct target of PPARγ [4]. When co-expressed in human HepG2 hepatoma cells, PPARγ stimulated the reporter activity driven by the G0S2 promoter via the PPRE sequence. In accordance, treatment with a PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone significantly increased G0S2 protein expression in cultured mouse adipocytes [8]. PPARγ is a highly expressed member of the PPAR family of nuclear receptor transcription factors in adipose tissue and functions as a master regulator of adipogenesis [22–26]. Activation of PPARγ and stimulation of its target genes are prerequisite for the acquisition of metabolic features specific to adipocytes, such as insulin-dependent fatty acid (FA) and glucose uptake, triacylglycerol (TG) synthesis and storage, adrenergically stimulated lipolysis, and synthesis and secretion of adipokines. The fact that G0S2 expression is upregulated by PPARγ during adipogenesis indicates that G0S2 may be involved in one or more of these adipose-specific functions promoted by PPARγ.

In addition to PPARγ agonism, the adipose expression of G0S2 is subject to regulation by various hormonal and nutritional conditions. In particular, G0S2 protein in adipocytes is upregulated by insulin and downregulated by β-adrenergic signals, suggesting a role for G0S2 in either promoting energy storage or inhibiting energy catabolism [8]. Consistent with this notion, G0S2 expression was found to be very low in adipose tissue during fasting but increased after feeding [7, 19]. Moreover, protein levels of G0S2 decrease in perigonadal fat depots and increase in mesenteric fat depots in high fat fed animals when compared with mice fed with chow diet [27]. In humans, a separate study found reduced mRNA and protein content of G0S2 in subcutaneous fat tissue from poorly controlled type 2 diabetic subjects [28]. Collectively, these studies suggest a potential role of G0S2 in the control of energy homeostasis at both physiologic and pathologic levels.

A major advance in understanding the function of G0S2 was the discovery that the TG hydrolase activity of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) can be selectively inhibited by G0S2 [8]. Lipolysis in adipocytes is mediated by cytosolic lipases that catalyze the hydrolysis of TG stores in lipid droplets (LDs) in response to fasting and/or caloric restriction. The most important, and rate-limiting lipase of TG hydrolysis is ATGL [29–34]. ATGL is a widely expressed enzyme that is responsible for catalyzing the first step in a sequence of three reactions in adipose TG hydrolysis. Inhibition of ATGL results in blocked lipolysis and ultimate accumulation of triglyceride if no compensatory mechanism is activated. Structurally, the N-terminal half of ATGL contains a predicted α/β-hydrolase fold and an overlapping patatin-like domain [35, 36]. The patatin domain is named after the potato tuber protein patatin [37], a weak acyl lipid hydrolase. The catalytic site of ATGL is located within the patatin-like domain and is characterized by an unconventional catalytic dyad similar to that of human cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) [35]. A hydrophobic stretch of 45 amino acids in the C-terminal region has been recognized to mediate targeting ATGL to the surface of TG-containing LDs [38, 39]. It is now known that the in vivo enzyme action of ATGL is decided not only by its lipase activity, but also by its LD localization and the interaction with a co-activator protein called CGI-58 (comparative gene identification-58; also known as α/β hydrolase fold containing protein 5, ABHD5) [39–44]. In humans, mutations of CGI-58 and ATGL were identified as a cause of various forms of neutral lipid storage disease characterized by TG deposition in multiple nonadipose tissues [45]. Clinical phenotypes that arise from mutations of CGI-58 differ slightly than those caused by ATGL mutations. Typically, CGI-58 mutations lead to a variety of conditions characterized by ichthyosis [46–50]. On the other hand, phenotypes that result from ATGL mutations are most often associated with skeletal and cardiomyopathies [51–55]. Both CGI-58 and ATGL mutations produce hepatomegaly and in certain instances liver steatosis [46–51, 53–55].

The inhibitory capacity of G0S2 on ATGL was originally characterized by Yang et al. [8], and subsequently confirmed by Coraciu et al. [43] and Schweiger et al. [21]. Immunofluorescence staining of G0S2 protein expressed in HeLa cells revealed the localization of G0S2 at the surface of LDs [8]. Studies employing co-expression approaches showed that G0S2 is able to prevent turnover of LDs mediated by ATGL. More importantly, it was determined that G0S2 directly interacts with ATGL and is capable of inhibiting the TG hydrolase activity of ATGL even under the CGI-58 co-activated conditions [8, 21, 39]. Mutagenesis analysis revealed that the hydrophobic domain of G0S2 and the patatin-like domain of ATGL are the primary regions of interaction, and an effective interaction is required for eventual inhibition of ATGL by G0S2 [8, 43]. Functionally, overexpression of G0S2 decreased both basal and hormone-stimulated lipolysis in cultured adipocytes and adipose tissue explants. Knockdown of endogenous G0S2, on the other hand, enhanced lipolysis in mature adipocytes [8, 21]. Collectively, these studies clearly prove that G0S2 is a unique inhibitor of ATGL and ATGL-catalyzed lipolysis.

Under physiologic conditions, adipose lipolysis is stimulated by β-adrenergic signals. In white adipocytes ATGL translocates to LDs following addition of a β-agonist isoproterenol to simulate lipolysis [8, 45]. Unexpectedly, it was demonstrated that endogenous G0S2 is simultaneously recruited to LDs through direct interaction with ATGL; knockdown of ATGL eliminated G0S2 localization to LDs [8]. A separate experiment demonstrated that C-terminally truncated ATGL mutants, which fail to localize to LDs, translocate to the LDs upon coexpression with G0S2 [21]. Therefore, ATGL and G0S2 are able to influence each other’s localization to LDs. The question arises as to why a lipolytic inhibitor such as G0S2 is needed at the LD surface when TGs are hydrolyzed. Although an unequivocal answer has to be derived from further investigation, we propose a model in which two cytosolic pools of ATGL, G0S2-bound and unbound, concomitantly undergo translocation onto LDs in adipocytes [8]. While translocation of unbound ATGL leads to acute activation of TG hydrolysis, prolonged adrenergic stimulation subsequently downregulates G0S2, thereby releasing G0S2-bound ATGL for sustained lipolysis. Furthermore, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) is known to potently stimulate basal lipolysis in adipocytes, which may contribute to hyperlipidemia and peripheral insulin resistance in obesity [56–58]. As surveyed in adipocytes, TNF-α drastically decreased expression of G0S2 at both messenger and protein levels [59]. Overexpression of G0S2, on the other hand, significantly decreased TNF-α-stimulated lipolysis mediated by ATGL with CGI-58 [59]. Therefore, it is speculated that early reduction in G0S2 content may be permissive for TNF-α-induced lipolysis.

4.2 G0S2 in liver, muscle and skin

In addition to its relatively high expression in adipose tissue, the expression of G0S2 is moderate in liver and lower in skeletal muscle and heart [4, 8]. While it is subject to regulation by PPARγ and increases under fed conditions in adipose tissue, G0S2 expression in liver is upregulated during chronic fasting and when PPARα is activated [4]. PPARα is well defined as the key regulator of FA catabolism in the liver [60]. G0S2 was differentially expressed between livers of PPARα-null mice and wild type mice indicates that hepatic G0S2 is a possible target gene of PPARα [4]. However, a direct activation of G0S2 expression by PPARα appears unlikely as overexpression of PPARα and treatment with PPARα agonist Wy14643 failed to stimulate the promoter activity of G0S2 in HepG2 cells [4].

G0S2 also contains a carbohydrate response element (ChoRE) within its promoter, allowing for direct responsiveness to glucose [61]. While investigating glucose-regulated gene expression in rat primary hepatocytes, Ma et al. discovered that the G0S2 promoter activity was induced by 2.5 fold when culture conditions were switched from low (5.5 mM) to high (27.5 mM) glucose. Deletion of the putative ChoRE sequence within the promoter blocked any response to glucose. Subsequent studies decisively identified G0S2 as a direct target of the ChREBP/Mlx dimer, a hybrid transcription factor that regulates the expression of glucose-responsive genes [61].

Compared to that in adipose tissue and liver, expression of G0S2 in muscle is less well studied. Like in adipocytes, insulin also has a profound stimulatory effect on G0S2 expression in skeletal muscle. Supporting evidence is derived from real time PCR analysis of G0S2 mRNA content in skeletal muscle biopsies collected from healthy human subjects after a euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp [6]. Another study showed that PPARβ/δ activation induces G0S2 expression in cardiac fibroblasts [3]. Although PPARβ/δ activation is known to attenuate cardiac fibrosis by inhibition of myofibroblast trans-differentiation [62], no evidence was provided to suggest a direct involvement of G0S2 in this downstream effect of PPARβ/δ.

Increased G0S2 expression was recently reported in skin cells isolated from patients with epidermolysis bullosa (EB) [63], a group of hereditary skin disorders characterized by blistering in response to minor injury, heat, or friction. Interestingly, there is a restriction in the release of FAs and glycerol from EB cells, though whether this is due to lipolytic inhibition mediated by G0S2 remains to be determined.

5. Perspectives & Discussion

Thus far, G0S2 has been best characterized in its anti-lipolytic role as an inhibitor of ATGL. While the majority of functional studies on G0S2 have been conducted in adipocytes, G0S2 is well expressed in liver and may be equally important in regulating hepatic lipid homeostasis. For example, in response to fasting, G0S2 expression decreases in adipose tissue but increases in liver [4, 7, 19]. This expression switch may serve to promote repartitioning of free fatty acids (FFAs), released via adipose lipolysis, to the liver. In fasting liver, very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) production and mitochondrial β-oxidation often cannot keep up with the FFA influx. Through inhibiting lipolysis and thus facilitating FA storage as TGs in LDs, G0S2 may play an important role in a defense mechanism against the potential cytotoxic effects of excess FFAs, which may include overproduction of cell-damaging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and impairment of insulin sensitivity. Evidence obtained earlier from liver-specific ATGL depletion suggests that lipolysis is required for preferential generation of FAs that can be used for synthesis of ligands or precursors of ligands for PPARα [64–66]. Therefore, though it experiences a marked increase during fasting, the endogenous G0S2 level may need to be delicately controlled so that sufficient ATGL action would still be allowed to mediate PPARα activation and FA oxidation.

In parallel with fasting conditions, models of mouse and human obesity also show decreased levels of G0S2 in WAT [7, 8]. It is possible that increased TNF-α production and impaired insulin sensitivity both contribute to the downregulation of G0S2 expression in adipocytes. We speculate that reduced levels of G0S2 lead to the increased basal lipolytic capacity that in turn results in the elevation of plasma FFA levels. In human obesity, increased plasma FFA levels may exacerbate peripheral lipotoxicity and thus, decreased G0S2 expression in adipocytes may be relevant for the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. The recent report demonstrating reduced adipose expression of G0S2 in type 2 diabetic humans supports this scenario [28]. Furthermore, it would also be interesting to evaluate the status of G0S2 in liver under obese conditions. Fasting, a condition that induces hepatic steatosis [67, 68], yields increased expression of G0S2 in liver. Interestingly, a similar increase in G0S2 protein levels occurs in the liver of mice with diet-induced obesity (X. Yang et al., unpublished data). An increased hepatic expression coupled with a decreased adipose expression of G0S2 may establish ideal conditions for enhanced TG storage and impaired FA oxidation in liver, contributing to the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

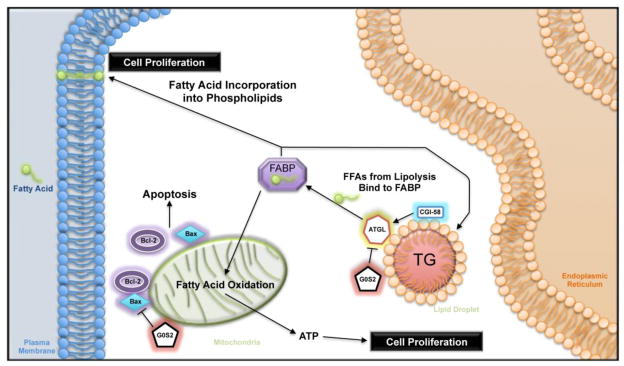

Clearly there are other mechanisms outside of post-mitotic cells in which G0S2 is functioning, including its ability to alter apoptosis and potentially proliferation and differentiation. These aspects of G0S2 may prove essentially important for the regulation of cancer development. We suspect that G0S2 most likely has a dual mechanistic function, one being ATGL-dependent and the other ATGL-independent (Fig.1). ATGL is broadly expressed and is a major regulator of metabolism in a variety of cell types. For the effective development and growth of cells, both energy and substrates for membrane biogenesis are required. Hydrolysis of TGs by ATGL may be required to provide FFAs that can further be processed for membrane synthesis or energy production through oxidation. In fact, when quiescent yeast reenters the cell cycle, cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) phosphorylates and activates the functional ATGL ortholog Tgl4 lipase, liquidating fat and providing FAs for cell-cycle entry [69]. In mammalian cells ATGL and G0S2 may be at the same crossroads of lipid metabolism and cell growth. It is certainly plausible that downregulation of G0S2 would contribute to increases in ATGL-mediated lipolysis, which in turn makes available the new FFAs to meet the proliferative needs. Suppression of G0S2 expression would be an ideal path for a growing cancer cell to ensure successful flow of needed substrates for membrane synthesis and energy production. Moreover, this mechanism needs not be limited to carcinogenesis, and may contribute to growth control of wild type cells as well.

Figure 1. ATGL-dependent and independent functions of G0S2.

G0S2 potentially regulates cell growth/survival in ATGL-dependent and independent fashions. By inhibiting ATGL-catalyzed lipolysis, G0S2 limits the availability of FFAs for membrane biogenesis and energy production, resulting in decreased proliferation. Separately, G0S2 can interact with Bcl-2, thereby disrupting the formation of the anti-apoptotic complex of Bcl-2 and Bax. This ATGL-independent function negatively impacts cell survival.

G0S2’s expression profile during adipocyte differentiation indicates a viable function in cell growth arrest. As also has been observed in HSCs, increased expression of G0S2 appears to be a key component in regulating or maintaining quiescence of stem cells [11]. Increasing evidence points to the dual roles of cell cycle regulators in the control of both cell proliferation and the adapted metabolic responses [70–73]. For example, in response to proliferative stimuli, the cdk-pRB-E2F complex can function to facilitate a switch from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism and subsequent channeling of the glycolytic products toward de novo FA synthesis [72, 73]. Despite a probable role of G0S2 in cell proliferation, however, it is unclear whether G0S2 possesses a regulatory function in cell cycle that is separate from its role as a lipolytic inhibitor.

Alternatively, G0S2 has been shown to localize to mitochondria and promote apoptosis by interacting with the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 [17]. This interaction, and other possible roles at the mitochondria, would also likely function in an ATGL-independent manner (Fig. 1). Downregulation of G0S2 expression could be a prime avenue for growing cells, especially cancer cells, in preventing death or/and growth arrest. Inhibition of apoptosis would be essential for continued proliferation and eventual homeostasis. While there is evidence as reported supporting G0S2’s pro-apoptotic function, it is important to note that this mechanism may be cell type-specific. For example, TNF-α treatment of cancer cells potently induces apoptosis and NF-kB-mediated G0S2 expression [17]. However, the presence of high levels of G0S2 do not seem to induce apoptosis in adipocytes, which are known to be quite resilient to apoptotic death [74]. TNF-α treatment of adipocytes significantly reduces G0S2 levels, resulting in increased lipolysis [59]. Further investigation is required to uncover the mechanisms underlying the current discrepancies in regard to the effect of TNF-α on G0S2 expression in different cell types.

In summary, the current evidence illustrates important and critical roles of G0S2 in a multitude of cell types. As usual, new insights raise many new questions. For example, what are the biochemical mechanisms by which G0S2 regulates ATGL, nucleolin and Bcl-2? What is the in vivo relevance of G0S2 in modulating energy metabolism, cell growth and apoptosis? Is the metabolic regulation mediated by G0S2 a crucial determinant of a cell’s decision to proliferate, differentiate or die? Elucidating the function of G0S2 and its regulation may be of great importance to our understanding of not only lipolysis, but also other physiologic and pathologic processes that ultimately depend on lipolytic outputs.

Highlights.

In this review we describe the G0/G1 switch gene 2 (G0S2) and its functions.

We illustrate the key features of G0S2’s localization, expression, and regulation.

We present the currently known functions of G0S2 in lipid metabolism and beyond.

We pose further questions and hypotheses for future research directions of G0S2.

Acknowledgments

Our research program is supported by National Institutes of Health DK089178 and a Junior Faculty Award from the American Diabetes Association to J.L.

Abbreviations

- G0S2

G0/G1 Switch Gene 2

- PKC

protein kinase C

- RA

retinoic acid

- PBMCs

peripheral mononuclear cells

- ATGL

adipose triglyceride lipase

- HSCs

hematopoietic stem cells

- TG

triacylglycerol

- FA

fatty acid

- FFA

free fatty acid

- FABP

Fatty acid binding protein

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- WAT

white adipose tissue

- PPRE

PPAR-responsive element

- LDs

lipid droplets

- cPLA2

human cytosolic phospholipase A2

- CGI-58

comparative gene identification-58

- ChoRE

carbohydrate response element

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor- alpha

- VLDL

very low density lipoprotein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- APL

promyelocytic leukemia

- RARE

retinoic acid response elements

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Russell L, Forsdyke DR. A human putative lymphocyte G0/G1 switch gene containing a CpG-rich island encodes a small basic protein with the potential to be phosphorylated. DNA Cell Biol. 1991;10:581–591. doi: 10.1089/dna.1991.10.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siderovski DP, Blum S, Forsdyke RE, Forsdyke DR. A set of human putative lymphocyte G0/G1 switch genes includes genes homologous to rodent cytokine and zinc finger protein-encoding genes. DNA and cell biology. 1990;9:579–587. doi: 10.1089/dna.1990.9.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teunissen BE, Smeets PJ, Willemsen PH, De Windt LJ, Van der Vusse GJ, Van Bilsen M. Activation of PPARdelta inhibits cardiac fibroblast proliferation and the transdifferentiation into myofibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zandbergen F, Mandard S, Escher P, Tan NS, Patsouris D, Jatkoe T, Rojas-Caro S, Madore S, Wahli W, Tafuri S, Muller M, Kersten S. The G0/G1 switch gene 2 is a novel PPAR target gene. Biochem J. 2005;392:313–324. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitareewan S, Blumen S, Sekula D, Bissonnette RP, Lamph WW, Cui Q, Gallagher R, Dmitrovsky E. G0S2 is an all-trans-retinoic acid target gene. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:397–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parikh H, Carlsson E, Chutkow WA, Johansson LE, Storgaard H, Poulsen P, Saxena R, Ladd C, Schulze PC, Mazzini MJ, Jensen CB, Krook A, Bjornholm M, Tornqvist H, Zierath JR, Ridderstrale M, Altshuler D, Lee RT, Vaag A, Groop LC, Mootha VK. TXNIP regulates peripheral glucose metabolism in humans. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen TS, Vendelbo MH, Jessen N, Pedersen SB, Jorgensen JO, Lund S, Moller N. Fasting, but not exercise, increases adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) protein and reduces G(0)/G(1) switch gene 2 (G0S2) protein and mRNA content in human adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1293–1297. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang X, Lu X, Lombes M, Rha GB, Chi YI, Guerin TM, Smart EJ, Liu J. The G(0)/G(1) switch gene 2 regulates adipose lipolysis through association with adipose triglyceride lipase. Cell Metab. 2010;11:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cristillo AD, Heximer SP, Russell L, Forsdyke DR. Cyclosporin A inhibits early mRNA expression of G0/G1 switch gene 2 (G0S2) in cultured human blood mononuclear cells. DNA and cell biology. 1997;16:1449–1458. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao A, Luo C, Hogan PG. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:707–747. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada T, Park CS, Burns A, Nakada D, Lacorazza HD. The cytosolic protein G0S2 maintains quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi S, Ito A, Okuzaki D, Onda H, Yabuta N, Nagamori I, Suzuki K, Hashimoto H, Nojima H. Expression profiling of PBMC-based diagnostic gene markers isolated from vasculitis patients. DNA Res. 2008;15:253–265. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verner J, Kabathova J, Tomancova A, Pavlova S, Tichy B, Mraz M, Brychtova Y, Krejci M, Zdrahal Z, Trbusek M, Volejnikova J, Sedlacek P, Doubek M, Mayer J, Pospisilova S. Gene expression profiling of acute graft-vs-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Exp Hematol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokumaru Y, Yamashita K, Osada M, Nomoto S, Sun DI, Xiao Y, Hoque MO, Westra WH, Califano JA, Sidransky D. Inverse correlation between cyclin A1 hypermethylation and p53 mutation in head and neck cancer identified by reversal of epigenetic silencing. Cancer research. 2004;64:5982–5987. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusakabe M, Watanabe K, Emoto N, Aki N, Kage H, Nagase T, Nakajima J, Yatomi Y, Ohishi N, Takai D. Impact of DNA demethylation of the G0S2 gene on the transcription of G0S2 in squamous lung cancer cell lines with or without nuclear receptor agonists. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2009;390:1283–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusakabe M, Kutomi T, Watanabe K, Emoto N, Aki N, Kage H, Hamano E, Kitagawa H, Nagase T, Sano A, Yoshida Y, Fukami T, Murakawa T, Nakajima J, Takamoto S, Ota S, Fukayama M, Yatomi Y, Ohishi N, Takai D. Identification of G0S2 as a gene frequently methylated in squamous lung cancer by combination of in silico and experimental approaches. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2010;126:1895–1902. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welch C, Santra MK, El-Assaad W, Zhu X, Huber WE, Keys RA, Teodoro JG, Green MR. Identification of a protein, G0S2, that lacks Bcl-2 homology domains and interacts with and antagonizes Bcl-2. Cancer research. 2009;69:6782–6789. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachner D, Ahrens M, Schroder D, Hoffmann A, Lauber J, Betat N, Steinert P, Flohe L, Gross G. Bmp-2 downstream targets in mesenchymal development identified by subtractive cloning from recombinant mesenchymal progenitors (C3H10T1/2) Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 1998;213:398–411. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199812)213:4<398::AID-AJA5>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh SA, Suh Y, Pang MG, Lee K. Cloning of avian G(0)/G(1) switch gene 2 genes and developmental and nutritional regulation of G(0)/G(1) switch gene 2 in chicken adipose tissue. Journal of animal science. 2011;89:367–375. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng F, Xie L, Pang X, Liu W, Nie Q, Zhang X. Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid cloning of avian G0/G1 switch gene 2, and its expression and association with production traits in chicken. Poultry science. 2011;90:1548–1554. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-01204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schweiger M, Paar M, Eder C, Brandis J, Moser E, Gorkiewicz G, Grond S, Radner FP, Cerk I, Cornaciu I, Oberer M, Kersten S, Zechner R, Zimmermann R, Lass A. G0/G1 switch gene-2 regulates human adipocyte lipolysis by affecting activity and localization of adipose triglyceride lipase. J Lipid Res. 2012 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M027409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79:1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren D, Collingwood TN, Rebar EJ, Wolffe AP, Camp HS. PPARgamma knockdown by engineered transcription factors: exogenous PPARgamma2 but not PPARgamma1 reactivates adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:27–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.953802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen ED, Hsu CH, Wang X, Sakai S, Freeman MW, Gonzalez FJ, Spiegelman BM. C/EBPalpha induces adipogenesis through PPARgamma: a unified pathway. Genes Dev. 2002;16:22–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.948702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annual review of biochemistry. 2008;77:289–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061307.091829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wueest S, Yang X, Liu J, Schoenle EJ, Konrad D. Inverse regulation of basal lipolysis in perigonadal and mesenteric fat depots in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E153–160. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen TS, Kampmann U, Nielsen RR, Jessen N, Orskov L, Pedersen SB, Jorgensen JO, Lund S, Moller N. Reduced mRNA and Protein Expression of Perilipin A and G0/G1 Switch Gene 2 (G0S2) in Human Adipose Tissue in Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1348–1352. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmermann R, Strauss JG, Haemmerle G, Schoiswohl G, Birner-Gruenberger R, Riederer M, Lass A, Neuberger G, Eisenhaber F, Hermetter A, Zechner R. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2004;306:1383–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1100747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haemmerle G, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Gorkiewicz G, Meyer C, Rozman J, Heldmaier G, Maier R, Theussl C, Eder S, Kratky D, Wagner EF, Klingenspor M, Hoefler G, Zechner R. Defective lipolysis and altered energy metabolism in mice lacking adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2006;312:734–737. doi: 10.1126/science.1123965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schweiger M, Schreiber R, Haemmerle G, Lass A, Fledelius C, Jacobsen P, Tornqvist H, Zechner R, Zimmermann R. Adipose triglyceride lipase and hormone-sensitive lipase are the major enzymes in adipose tissue triacylglycerol catabolism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40236–40241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bezaire V, Mairal A, Ribet C, Lefort C, Girousse A, Jocken J, Laurencikiene J, Anesia R, Rodriguez AM, Ryden M, Stenson BM, Dani C, Ailhaud G, Arner P, Langin D. Contribution of adipose triglyceride lipase and hormone-sensitive lipase to lipolysis in hMADS adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18282–18291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langin D, Dicker A, Tavernier G, Hoffstedt J, Mairal A, Ryden M, Arner E, Sicard A, Jenkins CM, Viguerie N, van Harmelen V, Gross RW, Holm C, Arner P. Adipocyte lipases and defect of lipolysis in human obesity. Diabetes. 2005;54:3190–3197. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villena JA, Roy S, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Kim KH, Sul HS. Desnutrin, an adipocyte gene encoding a novel patatin domain-containing protein, is induced by fasting and glucocorticoids: ectopic expression of desnutrin increases triglyceride hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47066–47075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dessen A, Tang J, Schmidt H, Stahl M, Clark JD, Seehra J, Somers WS. Crystal structure of human cytosolic phospholipase A2 reveals a novel topology and catalytic mechanism. Cell. 1999;97:349–360. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80744-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rydel TJ, Williams JM, Krieger E, Moshiri F, Stallings WC, Brown SM, Pershing JC, Purcell JP, Alibhai MF. The crystal structure, mutagenesis, and activity studies reveal that patatin is a lipid acyl hydrolase with a Ser-Asp catalytic dyad. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6696–6708. doi: 10.1021/bi027156r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shewry PR. Tuber storage proteins. Ann Bot. 2003;91:755–769. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcg084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zechner R, Kienesberger PC, Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Lass A. Adipose triglyceride lipase and the lipolytic catabolism of cellular fat stores. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:3–21. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800031-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu X, Yang X, Liu J. Differential control of ATGL-mediated lipid droplet degradation by CGI-58 and G0S2. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2719–2725. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.14.12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raben DM, Baldassare JJ. A new lipase in regulating lipid mobilization: hormone-sensitive lipase is not alone. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:35–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lass A, Zimmermann R, Haemmerle G, Riederer M, Schoiswohl G, Schweiger M, Kienesberger P, Strauss JG, Gorkiewicz G, Zechner R. Adipose triglyceride lipase-mediated lipolysis of cellular fat stores is activated by CGI-58 and defective in Chanarin-Dorfman Syndrome. Cell Metab. 2006;3:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radner FP, Streith IE, Schoiswohl G, Schweiger M, Kumari M, Eichmann TO, Rechberger G, Koefeler HC, Eder S, Schauer S, Theussl HC, Preiss-Landl K, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Hoefler G, Zechner R, Haemmerle G. Growth retardation, impaired triacylglycerol catabolism, hepatic steatosis, and lethal skin barrier defect in mice lacking comparative gene identification-58 (CGI-58) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7300–7311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cornaciu I, Boeszoermenyi A, Lindermuth H, Nagy HM, Cerk IK, Ebner C, Salzburger B, Gruber A, Schweiger M, Zechner R, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Oberer M. The minimal domain of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) ranges until leucine 254 and can be activated and inhibited by CGI-58 and G0S2, respectively. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Granneman JG, Moore HP, Krishnamoorthy R, Rathod M. Perilipin controls lipolysis by regulating the interactions of AB-hydrolase containing 5 (Abhd5) and adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl) J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34538–34544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schweiger M, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Eichmann TO, Zechner R. Neutral lipid storage disease: genetic disorders caused by mutations in adipose triglyceride lipase/PNPLA2 or CGI-58/ABHD5. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E289–296. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00099.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lefevre C, Jobard F, Caux F, Bouadjar B, Karaduman A, Heilig R, Lakhdar H, Wollenberg A, Verret JL, Weissenbach J, Ozguc M, Lathrop M, Prud’homme JF, Fischer J. Mutations in CGI-58, the gene encoding a new protein of the esterase/lipase/thioesterase subfamily, in Chanarin-Dorfman syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2001;69:1002–1012. doi: 10.1086/324121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srinivasan R, Hadzic N, Fischer J, Knisely AS. Steatohepatitis and unsuspected micronodular cirrhosis in Dorfman-Chanarin syndrome with documented ABHD5 mutation. The Journal of pediatrics. 2004;144:662–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schleinitz N, Fischer J, Sanchez A, Veit V, Harle JR, Pelissier JF. Two new mutations of the ABHD5 gene in a new adult case of Chanarin Dorfman syndrome: an uncommon lipid storage disease. Archives of dermatology. 2005;141:798–800. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ben Selma Z, Yilmaz S, Schischmanoff PO, Blom A, Ozogul C, Laroche L, Caux F. A novel S115G mutation of CGI-58 in a Turkish patient with Dorfman-Chanarin syndrome. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2007;127:2273–2276. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pujol RM, Gilaberte M, Toll A, Florensa L, Lloreta J, Gonzalez-Ensenat MA, Fischer J, Azon A. Erythrokeratoderma variabilis-like ichthyosis in Chanarin-Dorfman syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:838–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fischer J, Lefevre C, Morava E, Mussini JM, Laforet P, Negre-Salvayre A, Lathrop M, Salvayre R. The gene encoding adipose triglyceride lipase (PNPLA2) is mutated in neutral lipid storage disease with myopathy. Nat Genet. 2007;39:28–30. doi: 10.1038/ng1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hirano K, Ikeda Y, Zaima N, Sakata Y, Matsumiya G. Triglyceride deposit cardiomyovasculopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359:2396–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akiyama M, Sakai K, Ogawa M, McMillan JR, Sawamura D, Shimizu H. Novel duplication mutation in the patatin domain of adipose triglyceride lipase (PNPLA2) in neutral lipid storage disease with severe myopathy. Muscle & nerve. 2007;36:856–859. doi: 10.1002/mus.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campagna F, Nanni L, Quagliarini F, Pennisi E, Michailidis C, Pierelli F, Bruno C, Casali C, DiMauro S, Arca M. Novel mutations in the adipose triglyceride lipase gene causing neutral lipid storage disease with myopathy. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2008;377:843–846. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kobayashi K, Inoguchi T, Maeda Y, Nakashima N, Kuwano A, Eto E, Ueno N, Sasaki S, Sawada F, Fujii M, Matoba Y, Sumiyoshi S, Kawate H, Takayanagi R. The lack of the C-terminal domain of adipose triglyceride lipase causes neutral lipid storage disease through impaired interactions with lipid droplets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2877–2884. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cawthorn WP, Sethi JK. TNF-alpha and adipocyte biology. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:117–131. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen X, Xun K, Chen L, Wang Y. TNF-alpha, a potent lipid metabolism regulator. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009;27:407–416. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uysal KT, Wiesbrock SM, Marino MW, Hotamisligil GS. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF-alpha function. Nature. 1997;389:610–614. doi: 10.1038/39335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang X, Zhang X, Heckmann BL, Lu X, Liu J. Relative contribution of adipose triglyceride lipase and hormone-sensitive lipase to tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha)-induced lipolysis in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:40477–40485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.257923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mandard S, Muller M, Kersten S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha target genes. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2004;61:393–416. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma L, Robinson LN, Towle HC. ChREBP*Mlx is the principal mediator of glucose-induced gene expression in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28721–28730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holst D, Luquet S, Kristiansen K, Grimaldi PA. Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors delta and gamma in myoblast transdifferentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2003;288:168–176. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knaup J, Verwanger T, Gruber C, Ziegler V, Bauer JW, Krammer B. Epidermolysis bullosa - a group of skin diseases with different causes but commonalities in gene expression. Experimental dermatology. 2012;21:526–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2012.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haemmerle G, Moustafa T, Woelkart G, Buttner S, Schmidt A, van de Weijer T, Hesselink M, Jaeger D, Kienesberger PC, Zierler K, Schreiber R, Eichmann T, Kolb D, Kotzbeck P, Schweiger M, Kumari M, Eder S, Schoiswohl G, Wongsiriroj N, Pollak NM, Radner FP, Preiss-Landl K, Kolbe T, Rulicke T, Pieske B, Trauner M, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Hoefler G, Cinti S, Kershaw EE, Schrauwen P, Madeo F, Mayer B, Zechner R. ATGL-mediated fat catabolism regulates cardiac mitochondrial function via PPAR-alpha and PGC-1. Nat Med. 2011;17:1076–1085. doi: 10.1038/nm.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ong KT, Mashek MT, Bu SY, Greenberg AS, Mashek DG. Adipose triglyceride lipase is a major hepatic lipase that regulates triacylglycerol turnover and fatty acid signaling and partitioning. Hepatology. 2011;53:116–126. doi: 10.1002/hep.24006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu JW, Wang SP, Alvarez F, Casavant S, Gauthier N, Abed L, Soni KG, Yang G, Mitchell GA. Deficiency of liver adipose triglyceride lipase in mice causes progressive hepatic steatosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:122–132. doi: 10.1002/hep.24338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guan HP, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Liang G. Accelerated fatty acid oxidation in muscle averts fasting-induced hepatic steatosis in SJL/J mice. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24644–24652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.034397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Browning JD, Baxter J, Satapati S, Burgess SC. The effect of short-term fasting on liver and skeletal muscle lipid, glucose, and energy metabolism in healthy women and men. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:577–586. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P020867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kurat CF, Wolinski H, Petschnigg J, Kaluarachchi S, Andrews B, Natter K, Kohlwein SD. Cdk1/Cdc28-dependent activation of the major triacylglycerol lipase Tgl4 in yeast links lipolysis to cell-cycle progression. Mol Cell. 2009;33:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nature reviews Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Buchakjian MR, Kornbluth S. The engine driving the ship: metabolic steering of cell proliferation and death. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2010;11:715–727. doi: 10.1038/nrm2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fritz V, Fajas L. Metabolism and proliferation share common regulatory pathways in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:4369–4377. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aguilar V, Fajas L. Cycling through metabolism. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:338–348. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Magun R, Boone DL, Tsang BK, Sorisky A. The effect of adipocyte differentiation on the capacity of 3T3-L1 cells to undergo apoptosis in response to growth factor deprivation. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 1998;22:567–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]