SUMMARY

Research on the health of lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) adults generally overlooks the chronic conditions that are the most common health concerns of older adults. This brief presents unique population-level data on aging LGB adults (ages 50–70) documenting that they have higher rates of several serious chronic physical and mental health conditions compared to similar heterosexual adults. Although access to care appears similar for aging LGB and heterosexual adults, aging LGB adults generally have higher levels of mental health services use and lesbian/bisexual women report greater delays in getting needed care. These data indicate a need for general health care and aging services to develop programs targeted to the specific needs of aging LGB adults, and for LGB-specific programs to increase attention to the chronic conditions that are common among all older adults.

The number of adults age 65 and over in both California and the nation will double over the next 30 years as the baby boom generation ages. The nation’s older LGB population will increase even more, with estimates of 1.5 million LGB adults age 65 and older increasing to three million by 2030.1 Chronic health problems that are common among the elderly often start before age 65, with the prevalence of chronic and life-threatening health conditions increasing significantly starting in their fifties. The health of adults ages 50–70, therefore, foreshadows the health profile of the upcoming generation of older adults.

In California, an estimated 170,000 adults ages 50–70 (2.3%) identified as lesbian, gay or bisexual in 2007.2 Data from the 2003, 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Surveys show that aging LGB adults exhibit higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, poor mental health, physical disability and fair/poor self-assessed health compared to demographically similar aging heterosexual adults. Health differences are most common for men. Overall, aging LGB and heterosexual adults access health care services at similar rates; similar proportions have a usual source of care and actually obtain health care when it is needed. This policy brief provides the first data published on aging LGB adults that are based on a large statewide population. Knowing the patterns of health and health care of the aging LGB population in California is critical for improving state policy and practice to better address the needs of this group, and offers insights regarding trends that may be impacting the aging LGB population nationally.

Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Adults Ages 50–70: More Educated, Living Alone

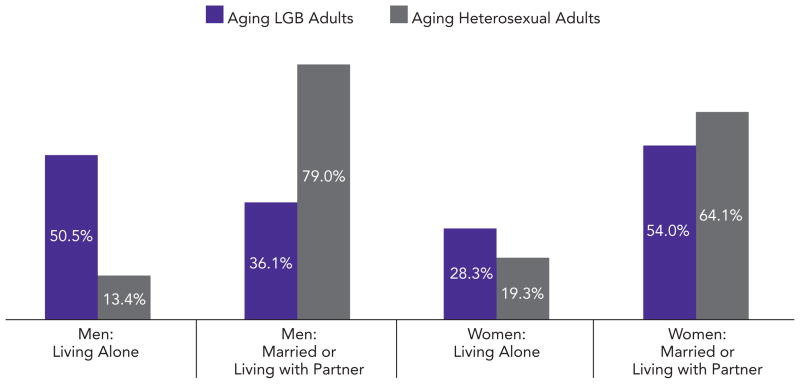

Aging LGB adults compared to aging heterosexual adults in California are typically at the younger end of the 50–70 year old age-range, less likely to be female, less likely to be members of a racial/ethnic minority, and have higher incomes and educational attainment (Exhibit 1). The largest differences are in the proportions of the LGB population that are persons of color (i.e., African American, American Indian, Asian American, Latino, NHOPI, other/mixed race: 22.5% of LGBs versus 40.9% of heterosexuals) and possess an advanced educational degree (35% of LGBs versus 16.6% of heterosexuals have some graduate level education).3 Despite the higher education and income of aging LGB adults than that of aging heterosexuals, they have a statistically similar rate of being uninsured (8.1% of LGBs versus 10.6% of heterosexuals; data not shown).

Exhibit 1.

Aging LGB and Heterosexual Adults by Selected Demographics, Ages 50–70, California, 2003–2007

* Low income is family income below 200% of the federal poverty level in the previous year: $26,400 for a couple in 2006.

Sources: 2003, 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Surveys

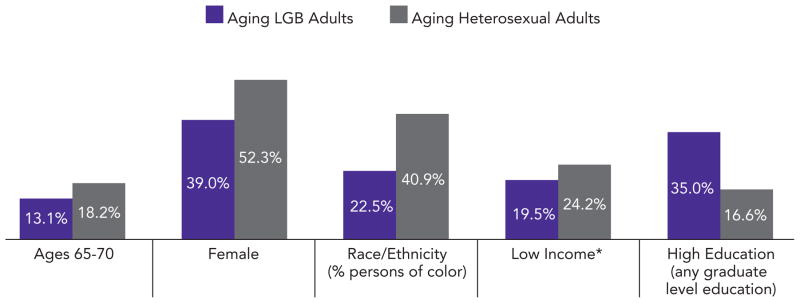

Striking differences exist by gender and marital status (Exhibit 2). Half of aging gay/bisexual adult men live alone compared to 13.4% of heterosexual men. About one-third of aging gay/bisexual adult men are married or living with a partner while more than three-fourths of heterosexual men are married or living with a partner. The rest of aging gay/bisexual adult men live with others but not with a spouse or partner. Differences in family structure are less drastic for aging lesbian/bisexual adult women than for men. However, more than one in four aging lesbian/bisexual adult women live alone compared to one in five heterosexual women. More than one-half of aging lesbian/bisexual adult women are married or living with a partner as are almost two-thirds of aging heterosexual adult women.

Exhibit 2.

Aging LGB and Heterosexual Adults by Gender and Living Arrangements, Ages 50–70, California, 2003–2007

Sources: 2003, 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Surveys

LGB adults face several unique challenges as they age. The majority have spent their early and middle adulthood creating independent and self-sufficient lives. Fewer LGB than heterosexual adults have children, so as they enter a time in life when support from children and biological kin are increasingly important to maintaining independence, these supports are less likely to be there than for heterosexual individuals.4 This is particularly true for men. As a result, the health of aging LGB adults ages 50–70 may differ, in both subtle and distinct ways, from that of their heterosexual counterparts.

The differences in social and demographic characteristics – such as education – are important as many of these factors are associated with better health status and access to health care. The analyses in Exhibits 3 and 4 use statistical procedures to control for these differences between aging LGB and heterosexual adults so that the results are presented as if the two groups had similar demographic characteristics. The analyses also compare aging LGB and heterosexual adults by gender because of their significant differences in family structures.

Exhibit 3.

Health Conditions Among LGB Men and Women and Risk Ratios Comparing Aging Gay/Bisexual Men and Lesbian/Bisexual Women to Aging Heterosexual Men and Women, Controlling for Age, Race/Ethnicity, Low-Income and Education, California, 2003–2007

| Health Conditions | Unadjusted Rate Among Gay/Bisexual (GB) Men, Ages 50–70 | Aging GB Men Compared to Aging Heterosexual Men After Adjusting for Population Differences (Relative Risk) | Unadjusted Rate Among Lesbian/Bisexual (LB) Women, Ages 50–70 | Aging LB Women Compared to Aging Heterosexual Women After Adjusting for Population Differences (Relative Risk) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Disease | 12.0% | 1.06 times higher, not significant | 8.3% | 1.06 times higher, not significant |

| Hypertension | 46.0% | 1.17* times higher | 35.7% | 1.05 times higher, not significant |

| Diabetes | 15.4% | 1.28* times higher | 10.5% | 1.32 times higher, not significant |

| Psychological Distress Symptoms (Kessler Score >6) (CHIS 2005 & CHIS 2007) | 22.3% | 1.45* times higher | 27.6% | 1.35* times higher |

| Physical Disability** (CHIS 2005 & CHIS 2007) | 24.2% | 1.24* times higher | 31.3% | 1.32* times higher |

| Fair/Poor Health Status | 25.8% | 1.50* times higher | 22.2% | 1.26* times higher |

Statistically significant difference between LGB and heterosexual aging adults at p ≤ .05.

Reports a condition that substantially limits one or more basic physical activities such as walking, climbing stairs, reaching, lifting or carrying.

Sources: 2003, 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Surveys unless otherwise noted

Exhibit 4.

Access to Care Among Aging LGB Men and Women, and Risk Ratios Comparing Aging Gay/Bisexual Men and Lesbian/Bisexual Women to Aging Heterosexual Men and Women, Controlling for Age, Race/Ethnicity, Insurance, Low-Income and Education, California, 2003–2007

| Access and Utilization in Past Year | Unadjusted Rate Among Gay/Bisexual (GB) Men, Ages 50–70 | Aging GB Men Compared to Aging Heterosexual Men After Adjusting for Population Differences (Relative Risk) | Unadjusted Rate Among Lesbian/Bisexual (LB) Women, Ages 50–70 | Aging LB Women Compared to Aging Heterosexual Women After Adjusting for Population Differences (Relative Risk) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delay of Care (CHIS 2003 & CHIS 2007) | 14.8% | 1.04 times higher, not significant | 25.8% | 1.28* times higher |

| Delay of Prescriptions (CHIS 2003 & CHIS 2007) | 14.1% | 1.21 times higher, not significant | 19.5% | 1.13 times higher, not significant |

| ER Visit | 18.6% | 1.07 times higher, not significant | 19.1% | 1.10 times higher, not significant |

| 3+ Doctor Visits | 63.2% | 1.19* times higher | 64.3% | 1.09* times higher |

| No Usual Source of Care (CHIS 2003 & CHIS 2005) | 6.7% | 0.97 times higher, not significant | 6.7% | 1.49 times higher, not significant |

Statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

Sources: 2003, 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Surveys unless otherwise noted

Aging Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Adults More Likely to Suffer from Some Chronic Conditions

Exhibit 3 shows several health conditions comparing aging gay/bisexual men with aging heterosexual men and aging lesbian/bisexual women with aging heterosexual women, after adjusting for differences in social and demographic characteristics. One factor we are unable to control for is HIV infection. From other estimates of the California population we anticipate that approximately one in five gay men in California is living with HIV infection, which is likely to affect several of the other conditions we examine.5

Gay and bisexual (GB) men ages 50–70 do not differ significantly from heterosexual men of the same age group in their rates of heart disease, after demographic differences have been taken into account. However, the ratio of hypertension, diabetes, psychological distress symptoms, physical disability and fair/poor health status is higher for aging GB men than for aging heterosexual men with similar demographics. Hypertension is the most common chronic health condition for both aging GB and heterosexual men. Less than one-quarter of aging GB men report psychological distress symptoms, but that rate is 1.45 times the rate of similar heterosexual men. Fair or poor self-assessed health status is a widely used measure of overall health problems. The rate of fair or poor health among aging GB men is 1.5 times higher than for aging heterosexual men with similar demographics.

Comparing aging lesbian and bisexual (LB) women with aging heterosexual women who are demographically similar, there is no statistical difference in these two groups for rates of heart disease, diabetes and hypertension. Aging LB women have a greater risk of experiencing psychological distress symptoms and physical disability than similar aging heterosexual women (1.35 times and 1.32 times, respectively). While there are fewer statistically significant differences in health conditions between aging LB and heterosexual women, a sizable proportion of LB women experience poor health conditions.

Health Care Service Access and Use Show Few Differences

While there are significant differences in the prevalence of several health conditions between aging LGB and heterosexual adults, there are few differences in our measures of access to health care services after we account for demographics.

Exhibit 4 shows that about one in seven of aging GB men reports delaying or not receiving medical care or prescriptions they felt they needed. After controlling for population differences, aging GB men were not significantly different from their heterosexual counterparts. Similarly, there were no statistically-significant differences between aging GB and heterosexual men in having an emergency room visit in the past year, or in having no usual source of care. Only the number of doctor visits in the past year was significantly different between the groups, with aging GB men 1.19 times more likely to have three or more visits in the past year, even after adjusting for demographics.

Among women, there were no statistically significant differences between aging LB and heterosexual women in delaying prescriptions, having an emergency room visit in the past year, or in having no usual source of care. However, one in four aging LB women reports delaying care they felt they needed, with aging LB women 1.28 times more likely to have delayed care than similar heterosexual women. LB women are also 1.09 times more likely to have three or more doctor visits in the past year, after adjusting for demographics.

Higher doctor use by aging LGB adults, especially for men, could be due to higher rates of health conditions or concerns that are in addition to the chronic conditions we profile, (e.g., about 32% of gay/bisexual men ages 50–70 reported an STD test in the past year compared to under 7% of heterosexual men.) Although this analysis provides data on basic access measures, it does not indicate whether or not the quality of that care was similar across populations. Past research has documented that discrimination, homophobia, and a lack of “cultural competence” can affect the quality of health care for lesbian, gay and bisexual adults.6

Policy and Practice Recommendations

As the number of LGB older adults rapidly increases, it is essential that health promotion and treatment for this population address the chronic conditions that affect older adults more generally, and account for aging LGB adults’ social and cultural characteristics and life experiences.

Increasing cultural competency and sensitivity among health care providers is a first step toward access to quality of care for aging LGB adults. Although the health care climate is improving for LGB patients seeking health care services, many have had prior experiences with prejudiced health care providers. Promoting awareness of aging LGB adults and providing resources for providers and organizations are key strategies used by organizations such as SAGE (Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Elders, www.sageusa.org) and the American Society on Aging, www.asaging.org/larc. In addition, the National Resource Center on LGBT Aging, www.lgbtagingcenter.org, was launched in 2010 as a federally-funded technical assistance provider to help create a community for providers, organizations and older adults with a focus on improving the quality of services available to the aging LGBT population.

Services that target the LGBT community also need to acknowledge the growing number of community members who have chronic conditions and may need supportive services. Examples of organizations that focus specifically on LGBT seniors include Gay & Lesbian Elder Housing (GLEH, www.gleh.org) in Los Angeles, which provides affordable housing, and Openhouse (www.openhouse-sf.org) in San Francisco, which provides housing and community services for LGBT older adults.

Aging LGB adults also encounter difficulties in gaining recognition for partners and families of choice. Without Medicaid and Social Security spousal benefits for same-sex partners, older LGB adults may face financial hardships.7 Policies that extend full benefits to same-sex partners can reduce financial barriers to health care faced by some aging LGB adults.

More research focused on the aging lesbian, gay and bisexual population is critical to creating and enhancing programs for this group, as well as focusing policy to address their needs. Because sexual orientation information is not collected in most population surveys, research on LGB elders has been limited to small studies, restricting how much we can generalize about the results.6 The California Health Interview Survey asks LGB identity as a standard demographic question, allowing us to provide a detailed look at the health status of aging LGB adults and factors influencing their access to health care. This type of data should be included in all major data systems in the state.

Mental Health Needs and Use of Services Higher for Aging LGB Adults.

Previous research has found that the lesbian, gay and bisexual populations have higher rates of mental health distress than the general population due to chronic social stressors, often rooted in stigma and discrimination.6 Data from CHIS 2007 show similar results with more than one-quarter of aging LGB adults (27.9%) reporting they needed help for emotional or mental health problems, compared to 14% of aging heterosexual adults. Among those who report needing help, aging LGB adults are more likely to seek help and see a health care professional for treatment (78.4% versus 66% of heterosexuals) and have a higher number of visits. Given the similarity in use of other health care services for aging LGB and heterosexual adults, the higher use of mental health services by the aging LGB adults may be due to a greater intensity of need to cope with day-to-day experiences of discrimination and/or less mental health support available from biological families.

Acknowledgments

Reviewer comments are gratefully acknowledged from Ron Anderson, Ilan H. Meyer, Mark Supper and Marty Martinson. Funding for this analysis and publication has been provided by The California Wellness Foundation (2008-299) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA 20826). The mission of The California Wellness Foundation is to improve the health of the people of California by making grants for health promotion, wellness education and disease prevention.

Footnotes

Data Source

The findings are based on the 2003, 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Surveys. The combined years include 1,052 aging LGB adults ages 50–70 who responded to the telephone surveys of households in every county in California. CHIS is conducted by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research in collaboration with the California Department of Public Health, the Department of Health Care Services and the Public Health Institute. For more information on CHIS, visit www.chis.ucla.edu.

Contributor Information

Steven P. Wallace, Associate director of the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and professor of Community Health Sciences at the UCLA School of Public Health.

Susan D. Cochran, Professor of Epidemiology at the UCLA School of Public Health.

Eva M. Durazo, Graduate student researcher at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

Chandra L. Ford, Assistant professor of Community Health Sciences at the UCLA School of Public Health.

Endnotes

- 1.Improving the Lives of LGBT Older Adults. 2010 Mar; http://www.lgbtmap.org/file/improving-the-lives-of-lgbt-older-adults.pdf.

- 2.This report categorizes sexual orientation based on the California Health Interview Survey question, “Do you think of yourself as straight or heterosexual, as gay {‘lesbian’} or homosexual, or bisexual?”

- 3.Because of discrimination, social stigma and cultural variations, persons of color and older adults are less likely to self identify as “gay or lesbian” and are therefore likely to be underrepresented in this data See DeBlaere C, Brewster ME, Sarkees A, Moradi B. Conducting Research With LGB People of Color: Methodological Challenges and Strategies. Counseling Psychologist. 2010;38(3):331–362.

- 4.Carpenter C, Gates GJ. Gay and Lesbian Partnership: Evidence from California. Demography. 2008;45:573–590. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Physical Health Complaints Among Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexual and Homosexually-Experienced Heterosexual Individuals: Results from the California Quality of Life Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:2048–2055. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Addis S, Davies M, Greene F, MacBride-Stewart S, Shephard M. The Health, Social Care and Housing Needs of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Older People: A Review of the Literature. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2009; 17(6):647–658; Fredriksen-Goldsen KI and Muraco A. Aging and Sexual Orientation: A 25-Year Review of the Literature. Research on Aging. 2010;32(3):372–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponce NA, Cochran SD, Pizer JC, Mays VM. The Effects of Unequal Access to Health Insurance for Same-Sex Couples in California. Health Affairs. 2010;29:1539–1548. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]