Abstract

The North Water polynya (~76°N to 79°N and 70°W to 80°W) is known to be an important habitat for several species of marine mammals and sea birds. For millennia, it has provided the basis for subsistence hunting and human presence in the northernmost part of Baffin Bay. The abundance of air-breathing top predators also represents a potential source of nutrient cycling that maintains primary production. In this study, aerial surveys conducted in 2009 and 2010 were used for the first time to map the distribution and estimate the abundance of top predators during spring in the North Water. Belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) were not detected north of 77°20′N but were found along the coast of West Greenland and offshore in the middle of the North Water with an abundance estimated at 2245 (95 % CI 1811–2783). Narwhals (Monodon monoceros) were widely distributed on the eastern side of the North Water with an estimate of abundance of 7726 (3761–15 870). Walruses (Odobenus rosmarus) were found across the North Water over both shallow and deep (>500 m) water with an estimated abundance of 1499 (1077–2087). Bearded (Erignathus barbatus) and ringed seals (Phoca hispida) used the large floes of ice in the southeastern part of the North Water for hauling out. Most polar bears (Ursus maritimus) were detected in the southern part of the polynya. The abundances of bearded and ringed seals were 6016 (3322–10 893) and 9529 (5460–16 632), respectively, and that of polar bears was 60 (12–292). Three sea bird species were distributed along the Greenland coast (eiders, Somateria spp.), in leads and cracks close to the Greenland coast (little auks, Alle alle) or widely in open water (thick-billed guillemots, Uria lomvia).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13280-012-0357-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: North Water, Polynya, Sea ice conditions, Top predators, Marine mammals, Sea birds

Introduction

Since William Baffin circumnavigated Baffin Bay in 1616, it has been known that there is an open-water area in northern Baffin Bay that does not freeze in winter. This polynya was recognized by Arctic whalemen as the North Water (~76°N to 79°N and 70°W to 80°W) and was frequently visited by whaling and exploring expeditions during the nineteenth century (Vaughan 1991). The area was attractive because of its year-round open-water conditions and its abundance of marine mammals, including commercially valuable bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus). For the same reasons, the area around the North Water had attracted Inuit hunting communities long before its discovery by Europeans. For some 4000 years, the North Water and adjacent areas with fast ice have functioned as the gateway from the Canadian Arctic for several waves of Inuit migrants who settled in Greenland and whose descendants persist in the modern Polar Inuit culture of Northwest Greenland.

The recurrent open water in northern Baffin Bay is maintained by the prevailing strong northerly wind from Smith Sound that, especially in years with an ice bridge across the narrowest point of Smith Sound, clears the area to the south of newly formed sea ice. This production and southward transportation of sea ice also brings water and nutrients from the deeper layers to the surface that help create a highly productive food web sustaining a large number’ of marine mammals and sea birds (Stirling 1980; Dunbar 1981)

The maritime Inuit subsistence hunting culture in Northwest Greenland is dependent on access to marine resources in the North Water (Born 1987), but the sustainability of recent levels of exploitation of some of those resources, especially walruses (Odobenus rosmarus) and narwhals (Monodon monoceros), has been questioned (NAMMCO 2010; Nielsen 2009). At the same time, the sea ice coverage in the North Water has declined in the 2000s compared to earlier decades (see “Results” section). It is therefore important to assess the abundance of ice-associated marine mammals in the North Water for at least two reasons: (1) to determine whether current harvest levels are sustainable and (2) to establish a baseline against which future changes in use of the North Water by marine mammals can be evaluated. In this article, distribution and abundance of marine mammals and sea birds in spring are described.

Materials and Methods

Survey Performance

Visual aerial line transect surveys were conducted as a double-observer experiment in a fixed-winged, twin-engined aircraft (DeHavilland Twin Otter) with a target altitude and speed of 213 m and 168 km h−1, respectively. The front (observer 1) and rear (observer 2) observers acted independently. Declination angles to sightings, species, and group size were recorded when the animals were abeam. Beaufort Sea state was recorded at the start of the day and then again when it changed. Decisions about duplicate detections (animals seen by both the observers 1 and 2) were based on coincidence in timing and location of sightings. Instrumentation of the plane and the procedures for data collection were identical to those previously reported by Heide-Jørgensen et al. (2010).

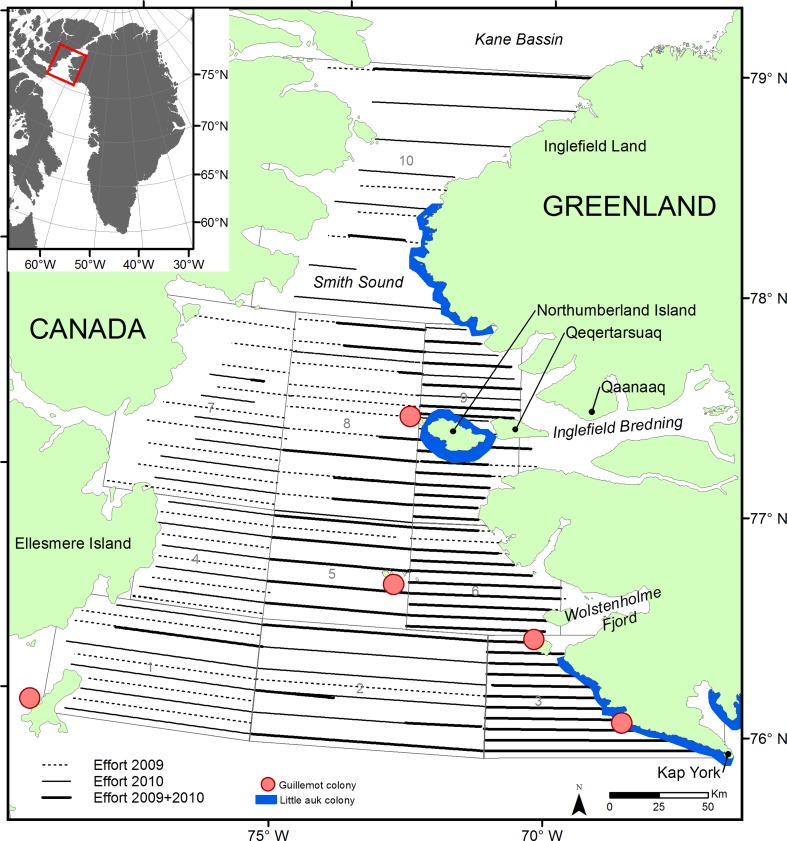

The surveys of the North Water were conducted during May 19–30, 2009 and May 20–29, 2010 and covered the area between 76°N and 79°N (~50 000 km2, Fig. 1). Ten strata were identified and they were surveyed by transects aligned east–west, systematically placed from the coast of West Greenland to Ellesmere Island, covering ~5400 km (Table 1). Some areas could not be surveyed due to unfavorable weather conditions (sea states ≥ 3 and horizontal visibility < 1 km). Observations were recorded of walruses, narwhals, belugas (Delphinapterus leucas), bowhead whales, ringed (Phoca hispida) and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus), and polar bears (Ursus maritimus). Flock sizes were estimated by the two front observers for three species of seabirds: little auk or dovekie (Alle alle), Brünnich’s guillemot or thick-billed murre (Uria lomvia), and eiders (Somateria spp.).

Fig. 1.

Transect lines and strata covered in the North Water during the surveys in May–June 2009 and 2010. Dotted lines Transects surveyed in 2009, thin solid lines 2010 transects, and thick solid lines transects surveyed in both years. Sea bird colonies are indicated for guillemots (red dots) and little auks (blue lines)

Table 1.

Survey effort and sightings; “/”separates data from 2009 and 2010

| Strata | Size (km2) 2009/2010 | Transects | Effort (km) 2009/2010 | Bowhead whale | Beluga | Narwhal | Walrus | Bearded seal | Ringed seal | Polar bear |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5773/5615 | 5/6 | 456/524 | 2/18 | 3/2 | 11/5 | /7 | /1 | ||

| 2 | 7458/7458 | 5/6 | 428/700 | /1 | 2/9 | 3/3 | /3 | /10 | /48 | /1 |

| 3 | 4161/4233 | 11/12 | 696/714 | /1 | 19/7 | 8/7 | 2/10 | 4/30 | 1/91 | /1 |

| 4 | 3271/3283 | 5/6 | 300/348 | /3 | 8/1 | 1/6 | /11 | /2 | ||

| 5 | 3970/3954 | 6/5 | 419/360 | 11/11 | 6/1 | 5/2 | 2/2 | /7 | ||

| 6 | 3533/3375 | 11/11 | 720/626 | 8/7 | 6/7 | /21 | /67 | |||

| 7 | 6329/4684 | 9/6 | 548/267 | 2/ | 2/ | 1/1 | 2/4 | 1/5 | ||

| 8 | 6774/6772 | 11/7 | 812/461 | 4/3 | 16/5 | 2/ | 3/1 | |||

| 9 | 4152/3557 | 17/26 | 648/836 | 7/7 | 11/13 | 1/1 | /24 | /8 | ||

| 10 | 9418/8294 | 5/8 | 457/563 | /1 | 2/4 | /3 | 2/ | |||

| Total | 54 839/51 223 | 85/93 | 5483/5398 | /2 | 47/58 | 54/36 | 26/28 | 23/106 | 5/248 | 2/5 |

Columns 5–11 show the numbers of unique sightings for each species (for belugas, narwhals, and walruses a sighting consist of a group of individuals seen within 2 body lengths of each other)

Collection of Data on the Availability Correction

To obtain data for use in correcting visual aerial surveys to account for whales and walruses submerged below the detection depth (Richard et al. 1994; Heide-Jørgensen 2004), two female narwhal and three female walruses were tagged with satellite-linked time-depth recorders (Mk10a SLTDRs Wildlife Computers, cf. Dietz and Heide-Jørgensen 1995, see Electronic Supplementary Material). Measurements of the time spent above 2 m depth were collected in 6-h bins, relayed through the Argos Data Collection and Location System and decoded using Argos Message Decoder (Wildlife Computers). Daily averages were calculated for daylight hours and used for deriving monthly averages that, to the extent possible, matched the survey area and dates (see Table S12). Data from one of the whales were collected during the 2009 aerial survey and augmented samples that had been used to derive an earlier correction factor (see Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2010). Three walruses were tagged with SLTDRs in May–June 2010 and 2011 in the North Water by use of Inuit hand harpoons (see Fig. 2) and data on surfacing time were collected in the same area and during the same time period as the aerial surveys. For belugas, the mean of at-surface availability factors used in previous surveys (Heide-Jørgensen and Acquarone 2002) was applied to this survey while a value from Born et al. (2002) was used for ringed seals. In the absence of a species-specific value for bearded seals, the correction factor for ringed seals was applied.

Fig. 2.

Tagging of a walrus in the North Water in 2010 with satellite-linked time-depth-recorders for measurements of time spent at the surface available for detection by the visual aerial surveys

Development of Abundance Estimates

The declination angles to sightings when animals were abeam were converted to radial distances using the equation from Lerczak and Hobbs (1998a, b). Although the observers were acting independently, dependence of detection probabilities on unrecorded variables can induce correlation in detection probabilities. As it may not be possible to record all variables affecting detection probability, unmodelled heterogeneity may persist even when the effects of all recorded variables are modelled. Laake and Borchers (2004) and Borchers et al. (2006) developed an estimator based on the assumption that there is no unmodelled heterogeneity except at zero perpendicular distance (i.e., on the trackline)—called a point independence estimator. The alternative—a full independence estimator—assumes no unmodelled heterogeneity at any distance. The point independence model is more robust to the violation of the assumption of no unmodelled heterogeneity than the full independence model and was therefore used.

Incorporating the point independence assumption involves estimating two models: a multiple covariate distance sampling (DS) detection function for combined platform detections, assuming certain detection on the trackline (Marques and Buckland 2004) and a mark-recapture (MR) detection function to estimate detection probability at distance zero for an observer. The MR detection function is the probability that an animal at given perpendicular distance x with covariates z, which was detected by an observer q (q = 1 or 2), given that it was seen by the other observer, which is denoted by  It is modelled using a logistic form:

It is modelled using a logistic form:

|

1 |

where β0, β1,…, βk+1 represent the parameters to be estimated and K is the number of covariates other than distance. Note that if observer is included as an explanatory variable, then  will not be equal to

will not be equal to  . The intercepts (i.e., at x = 0) of

. The intercepts (i.e., at x = 0) of  and

and  are combined to estimate their detection probability on the trackline by at least one observer.

are combined to estimate their detection probability on the trackline by at least one observer.

For the DS model, both half-normal and hazard rate functions were fitted, initially with no covariates (apart from perpendicular distance) and then covariates were included via the scale parameter (Marques and Buckland 2004). The available covariates were group size, side of plane (left and right), and (average) Beaufort Sea state. Group size and Beaufort Sea state were included either as non-factor variables or as factor variables; group size was converted to a factor variable with two levels to represent groups of size one and greater than one, while Beaufort Sea state was included as a factor variable with three levels to represent Beaufort Sea states 0, 1, and ≥2. The same covariates were included in the MR model, in addition to a variable indicating observer (1 and 2). Akaike’s information criterion (AIC, see Buckland et al. 2001) and goodness-of-fit tests were used for model selection.

Density (D) and abundance (N) of individual animals in a stratum were obtained using

|

2 |

where within each stratum, sj is the recorded size of group j, A is the size in km2 of the stratum, w is the truncation distance, L is the total effort in km, n is the number of unique detections, and  is the estimated probability of detecting group j (perception bias), obtained from fitted mark recapture distance sampling (MRDS) models as described in Heide-Jørgensen et al. (2010).

is the estimated probability of detecting group j (perception bias), obtained from fitted mark recapture distance sampling (MRDS) models as described in Heide-Jørgensen et al. (2010).

To account for availability bias, corrected abundance (denoted by the subscript “c”) was estimated by

|

3 |

where the parameter  is the estimated proportion of time animals are available for detection. The coefficient of variation (CV) of

is the estimated proportion of time animals are available for detection. The coefficient of variation (CV) of  was given by

was given by

|

4 |

MRDS models require a sufficient number of sightings to estimate the model parameters reliably. A simpler MR model developed by Chapman (1951) was based on only the numbers of sightings and duplicates, and thus assumes that detection does not depend on perpendicular distance. The number of groups in the covered region for the Chapman estimator was given by

|

5 |

where nq is the number of groups detected by observer q and m is the number of duplicates. The variance was given by

|

6 |

This estimator will be negatively biased if distance, or other covariates, affects detection probability. With the Chapman estimator, the average group size,  , is used to convert group abundance to animal abundance as follows:

, is used to convert group abundance to animal abundance as follows:

|

7 |

When too few sightings and duplicates were recorded to account for detection probability the following strip transect estimator was used to estimate the density and abundance of groups:

|

8 |

The average group size was used to convert group abundance to individual abundance as in Eq. (7). This estimate will be negatively biased if detectability is not certain within the truncation distance w.

For animals that haul-out on ice, at any one time, the total number in the region will consist of animals on the ice plus those in the water. For walrus, the total numbers of groups was scaled up for the entire study region as follows:

|

9 |

where  is the number of groups on ice in the covered region and

is the number of groups on ice in the covered region and  is the number of groups in the water in the covered region. In this way, both perception bias and availability bias have been accounted for (animals on ice are assumed to be always available for detection). The average group sizes of walruses in the water and on the ice were multiplied by the number of groups to obtain the number of individuals. Total abundance was estimated using the number of individuals, rather than the number of groups, estimated to be on the ice or in the water in the covered region. The total number of walruses detected within the covered area based on a strip width of 300 m was scaled to the study region and corrected for availability bias.

is the number of groups in the water in the covered region. In this way, both perception bias and availability bias have been accounted for (animals on ice are assumed to be always available for detection). The average group sizes of walruses in the water and on the ice were multiplied by the number of groups to obtain the number of individuals. Total abundance was estimated using the number of individuals, rather than the number of groups, estimated to be on the ice or in the water in the covered region. The total number of walruses detected within the covered area based on a strip width of 300 m was scaled to the study region and corrected for availability bias.

The impacts of using different mean or maximum group size estimates from the two sets of observers were explored and the estimates were not significantly different.

Confidence intervals were estimated using the log-based method given in Buckland et al. (2001) and further details of the abundance estimation procedures are provided in Electronic Supplementary Material.

Sea Ice Data

Data on sea ice concentration from satellite passive microwave sensors were obtained from the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado, USA (Cavalieri et al. 2010). During the period 1979–1987, data were acquired every other day and linear interpolation was used to make daily values. During the period 1987–2011, data were acquired daily. The sea ice area in the North Water was computed as the daily extent from March to June in the region bounded by 76°N and 79°N.

Results

Sea Ice Conditions in the North Water

An unusually large proportion (>80 %) of the North Water had open-water conditions, with no signs of recent ice formation, in late May 2009 (Fig. 3). Larger stretches of fast ice could be found only along the east coast of Ellesmere Island. On the Greenland side, no fast ice was evident along the outer coast from Kap York to north of Inglefield Land. The Wolstenholme Fjord on the Greenland side had broken fast ice with the ice edge reaching unusually far into the fjord. The Inglefield Bredning fjord had fast ice with an ice edge at the eastern corner of the island Qeqertarsuaq. In Smith Sound, transects were flown as far north as 79°N without detection of sea ice except for fast ice along Ellesmere Island. Sea ice could not be seen from the aircraft north of 79°N and Kane Basin had unprecedented low sea ice coverage (<25 %) in 2009 (GINR, unpublished data). In May 2010, the recession of the sea ice was less than in 2009 and large fields of pan ice were still present especially in the southeastern part of the North Water (Fig. 3). Also, Kane Basin had twice the sea ice coverage in 2010 compared to 2009 (GINR, unpublished data). The sea ice coverage in the North Water was estimated at ~4000 and ~10 000 km2 on June 1, 2009 and 2010, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Visible-band images from the MODIS instrument on NASA’s Aqua satellite showing open-water areas (black) in the North Water on May 23, 2009 (left) and on May 29, 2010 (right)

Sea ice in the North Water usually shows a peak in extent of distribution in March, then a decline during April and May until open water prevails in June–July. There is considerable annual variation in the extent of ice coverage in all months (Fig. 4a). There is also large daily or weekly variation in the ice coverage caused by shifting meteorological conditions in the North Water. However, decadal averages show a marked difference between the ice coverage in 1982–1991 and 2002–2011. During the 2000s, the date of 50 % open water in the polynya was reached about 2 weeks earlier, on average, than in the 1980s (Fig. 4a). In the 2 years with surveys, the 50 % open-water level was reached around May 1, 2009 and around May 25, 2010, again confirming the large interannual variability.

Fig. 4.

Development of sea ice extent in a the North Water and b Baffin Bay based on satellite data during March–June for the years 1979–-2011 with all years shown as gray lines and 10 year averages shown in blue (1982–1991), green (1992–2001), and red (2002–2011). Dates of the surveys (May 19–30) are shown as vertical dotted lines

Search Effort and Sightings

The total realized search effort for the two surveys was nearly identical although inclement weather conditions reduced the effort in strata 7 and 8 in 2010 to about half the effort in 2009, whereas most other strata had more effort in 2010 (Table 1). The reduced effort in strata 7 and 8 in 2010 apparently also reduced the number of sightings of narwhals, whereas the other species, except seals, had fairly similar total number of sightings. Both ringed and bearded seals were seen more frequently in 2010 due to the larger ice coverage especially in strata 2 and 3.

For some duplicate sightings, the observers had recorded different declination angles and thus the sightings had different perpendicular distances; however, no systematic bias between the observers could be detected (see Figs. S3 and S4). Therefore, the mean perpendicular distance for the duplicate sightings was used.

Similarly, the majority of sightings were of single animals but for some duplicate sightings, observers had recorded different group sizes. In the majority of cases, the difference between the two estimates was one animal and for the analysis, the mean group size was used (see Table S6).

All effort in 2009 was in Beaufort Sea state <3 but in 2010 an average Beaufort Sea state, weighted by search effort, was calculated for each transect and used in the following analysis. The majority of the effort was completed in sea states <3 with 2/3 of the effort in sea state zero.

Detection Functions

The detection probability may not be at a maximum on the trackline if it is difficult to see directly below the plane. However, the histograms of the perpendicular distributions for both observers combined do not suggest that there was a problem searching below the plane (see Figs. S5–S10), except for ringed seals on the ice where the probability of detection appeared to be lower within 100 m of the trackline (see Fig. S10). In this case, the data were left truncated at 100 m (i.e., the transect was offset by 100 m). The covariates included in the final MRDS models varied among whales, seals, and year (Table 2). Beaufort Sea state, side of the plane, and group size of the sightings were included in most models, whereas observer was only included as a covariate for the seals. The MRDS estimator was used to estimate bearded seal and ringed seal abundance on the ice where >90 % of the seals were detected. About 19 and 32 % of the walruses were detected on ice in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Due to the relatively few sightings of walruses, the Chapman estimator was used in both years and a half-strip width with constant detection probability out to 300 m (see Fig. S8) was applied to both years.

Table 2.

Covariates included in the final MRDS models and the AIC values

| Species | Years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | |||||

| DS model | MR model | AIC | DS model | MR model | AIC | |

| Beluga | BF3 + size2 | D + BF + size | 682.92 | Size2 | BF3 | 852.24 |

| Narwhal | BF + side2 | Size + side2 | 790.42 | – | Side2 | 505.42 |

| Bearded seals on ice | na | na | na | BF3 + side2 | Obs2 | 1442.50 |

| Ringed seals on ice | na | na | na | Size | Side2 + obs2 | 3258.06 |

The covariates are perpendicular distance (D), group size (size), Beaufort Sea state (BF), and side of plane (side). The dash indicates that no covariates were included in the scale parameter in the DS model. Subscript indicates that the variable was fitted as a factor variable with the number of levels indicated by the subscript. The “DS model” column shows the explanatory variables that were included via the scale parameter; no additional variables were included for walrus

Probability of Detection on the Trackline

The probability of detection on the trackline by at least one observer in 2009 was estimated to be 0.97 (CV 0.02) for beluga, 0.81 (0.06) for narwhal, and 0.82 (0.11) for walrus in the water. In 2010, the probabilities were 0.92 (0.03) for beluga and 0.85 (0.06) for narwhal. For seals on the ice, it was estimated to be 0.57 (0.08) for bearded seals and 0.60 (0.05) for ringed seals. The 2010 estimates for walrus suggested that walruses were more detectable in the water (0.70, CV 0.15) than on the ice (0.38, CV 0.35) but both estimates, particularly the latter, are based on a small numbers of sightings.

Distribution and Abundance Estimates

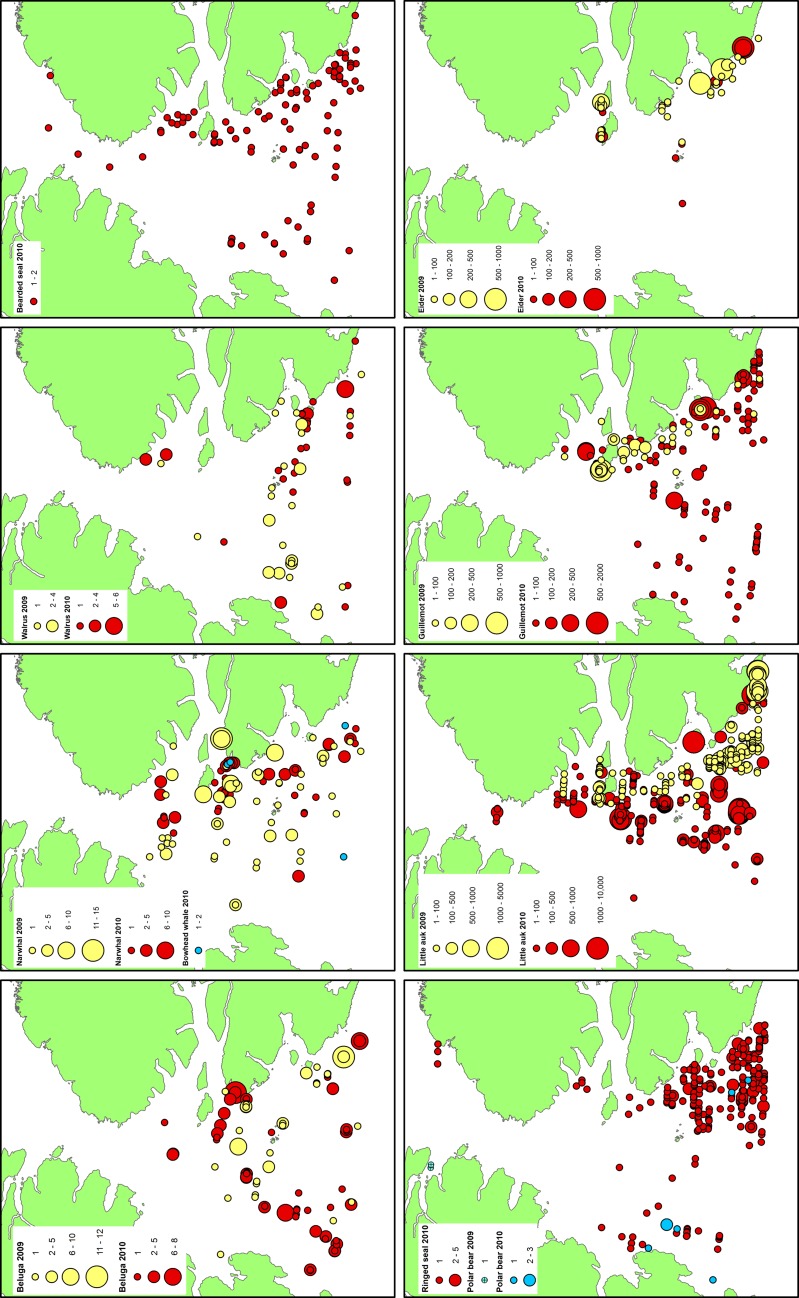

No belugas were detected north of 77°20′N in either year although they were found both along the coast of West Greenland and offshore in the middle of the North Water (Fig. 5). Two-thirds of the observations were of solitary whales and the average swim direction of 23 beluga groups was southwest (232°). In 2009, the individual abundance (corrected for perception bias) of belugas was estimated to be 863 (CV 33; 95 % CI 460–1620) and in 2010 it was estimated to be 1067 (CV 27; 95 % CI 636–1792). Belugas were considered to be available for detection when they were within 5 m of the surface and time-depth-recorder data indicated that belugas spend on average 43 % of the time above 5 m depth (CV 9, Table 3). The fully corrected average abundance of belugas in the North Water for the 2 years with surveys was 2245 (CV 0.11, 95 % CI 1811–2783, Table 4).

Fig. 5.

Observations of whales, walruses, seals, and three sea birds during the aerial survey of the North Water in May–June 2009–2010

Table 3.

Availability bias factors based on satellite-linked time-depth-recorders deployed on belugas, narwhals, walruses, and ringed seals

| Species | n | Source of data | Availability bias factor | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beluga | 18 | Mean of six samples from November to January | 0.43 (0.09) | Heide-Jørgensen and Acquarone (2002) |

| Narwhal | 2 | Mean from May and June 2007 and 2008 in northern Baffin Bay | 0.15 (0.14) | Heide-Jørgensen et al. (2010) and GINR (unpublished data) |

| Walrus in water | 3 | Mean of walruses tagged in the North Water in May 2009 and 2010 | 0.35 (0.10) | GINR (unpublished data) |

| Ringed seals on ice | 7 | Mean from June 1998 and 1999 from the North Water | 0.41 (0.24) | Born et al. (2002) |

The CV is given in parentheses

Table 4.

Abundance estimates corrected for perception and availability bias (CVs shown in parentheses) and average annual reported catches between 1993 and 2010 for the municipality of Qaanaaq (http://dk.nanoq.gl/emner/erhverv/erhvervsomraader/fangst_og_jagt/piniarneq.aspx)

| Strata | Beluga [0.43 (0.09)] | Narwhal [0.15 (0.14)] | Walrus [0.35 (0.10)] | Bearded seal [0.41 (0.24)] | Ringed seal [0.41 (0.24)] | Polar bear | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2009 | 2010 | 2009 | 2010 | 2010 | 2010 | 2010 | |

| 1 | 64 (1.03) | 894 (0.34) | 0 | 0 | 143 | 126 | 471 (0.78) | 411 (0.88) | 12 |

| 2 | 222 (0.95) | 412 (0.77) | 720 (0.59) | 433 (0.71) | 0 | 188 | 844 (0.52) | 2722 (0.38) | 12 |

| 3 | 848 (0.58) | 276 (0.59) | 1029 (0.57) | 935 (0.54) | 95 | 628 | 1265 (0.37) | 2852 (0.31) | 12 |

| 4 | 0 | 220 (0.69) | 0 | 0 | 380 | 63 | 389 (0.45) | 545 (0.74) | 24 |

| 5 | 370 (0.52) | 378 (0.90) | 984 (0.38) | 158 (1.02) | 238 | 126 | 183 (0.72) | 350 (1.03) | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 1305 (0.56) | 645 (0.53) | 286 | 439 | 740 (0.39) | 1746 (0.37) | 0 |

| 7 | 133 (1.00) | 0 | 355 (0.98) | 0 | 48 | 63 | 516 (0.97) | 476 (0.58) | 0 |

| 8 | 223 (0.88) | 150 (1.10) | 1855 (0.48) | 1159 (0.90) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 95 (1.12) | 0 |

| 9 | 148 (0.91) | 151 (0.58) | 4429 (0.50) | 1445 (0.54) | 48 | 63 | 748 (0.35) | 191 (0.44) | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 860 (0.55) | 140 (0.95) | 0 |

| Total | 2008 (0.34) | 2482 (0.28) | 10 677 (0.29) | 4775 (0.36) | 1238 (0.19) | 1759 (0.29) | 6016 (0.31) | 9529 (0.29) | 60 (0.96) |

| Catches 1993–2010 | 24 | 120 | 112 | 215 | 4183 | 27 | |||

| Quotas 2012 | 20 | 85 | 64 | na | na | 24 | |||

Narwhals were widely distributed on the eastern side of the North Water during the survey with the core distribution around 77°09′N, 72°W close to the southern entrance of Inglefield Bredning (Fig. 5). There were also several sightings of narwhals north of Inglefield Bredning at the latitude of 77°42′N and closer to Ellesmere Island than to Greenland. Narwhals were detected mainly in deep water (>500 m) and two-thirds of the detections were of single animals although a few larger groups (5–10 individuals) were observed on the Greenland side of the North Water. In 2009, the at-surface abundance of narwhals (corrected for perception bias) was estimated to be 1602 (CV 0.25; 95 % CI 982–2610) and in 2010 it was estimated to be 716 (CV 0.33; 95 % CI: 382–1344). Narwhals were considered to be available for detection when they were within 2 m of the surface and time-depth-recorder data indicated that narwhals spend about 15 % of the time above 2 m depth (CV 0.14). The fully corrected average abundance of narwhals for the 2 years with surveys was 7726 (CV 0.38; 95 % CI 3761–15 870). Bowhead whales were seen on four occasions in the southern and eastern parts of the polynya.

Most of the walruses were distributed on a belt from Greenland to Ellesmere Island in the southern part of the North Water at a latitude of ~76°30′N, in both shallow and deep (>500 m) water. Only three sightings were north of 77°N with the northernmost at 77°48′N (Fig. 5). Walruses in the water were assumed to be available for detection when they were within the top 2 m from the surface and it was estimated that they spend 35 % (CV 0.10) of the time at this depth. This estimate was obtained from tagging three walruses with satellite-linked, time-depth recorders, and recording data in May–June 2009 and June 2010 (Fig. 2; Table 3). The estimated number of walruses in the water in the covered region was corrected for availability bias using this factor. Most walruses were detected as solitary individuals but three groups of four animals and one of six were seen. The average abundance of walruses was 1499 (CV 0.17; 95 % CI 1077–2087).

Bearded and ringed seals were detected primarily on ice and thus only 2010, when ice cover was more extensive, provided data on distribution of these two species. Both species were using the large ice floes in the southeastern part of the North Water to haul-out. Abundance estimates for seals on the ice, corrected for observer perception bias were estimated to be 2448 bearded seals (CV 0.19; 95 % CI 1687–3553) and 3878 ringed seals (CV 0.15; 95 % CI 2873–5234). To estimate total seal abundance, the availability of seals on the ice was required. Born et al. (2002) estimated that ringed seals spent 40.7 % (CV 0.24) of the time hauled out on the ice (Table 3). No equivalent estimates were available for bearded seals so this estimate was used to correct both the ringed seal and the bearded seal on-ice abundance to obtain total abundance estimates. The fully corrected abundance estimates of bearded and ringed seals in 2010 were 6016 (CV 0.31; 95 % CI 3322–10 893) and 9529 (CV 0.29; 95 % CI 5460–16 632), respectively.

Although polar bears were detected both on ice and in the water, these data were combined since so few bears were detected. A truncation distance of 555 m, corresponding to the maximum distance of sightings, was used to calculate a strip census estimator of the covered region. The abundance estimate was 60 polar bears (0.96; 12–293).

The three sea bird species were distributed along the Greenland coast (eiders), in leads and cracks close to the Greenland coast (little auks) or widely in open water across the North Water (guillemots). The presence of sea ice along the coast in the southeastern part of the polynya caused the little auks to be present significantly further offshore in 2010 implying a longer flight distance from the coastal colonies (t test; p < 0.001, Fig. 5).

Discussion

The large amount of open water (>80 %) detected in the North Water area during the late May aerial survey in 2009 was unusual for the season compared to the 1980s and 1990s (Fig. 4a), when ice coverage in late May was generally 40–80 % in the main part with open water only in northern Smith Sound and fast ice prevailing in all fjords and along shores (Barber et al. 2001). The lack of sea ice during the 2009 survey affected the whales and seals differently by allowing the whales access to a larger proportion of the region but providing fewer opportunities for walruses and seals to haul-out on ice. Walruses could use terrestrial haul-outs instead of sea ice but no seal species are known to haul-out on land in the North Water. Sea birds had open water closer to their colonies in 2009 but little auks, in particular, had to fly longer distances in 2010 to reach open water to locate their prey that in spring almost exclusively consist of calanoid copepods (Karnovsky et al. 2008). Longer flight routes have probably elevated energetic costs but could be compensated by higher copepod densities due to more strict timing of spring bloom development (Laidre et al. 2008). Guillemots rely more on polar cod and Themisto libellula, and their distribution from colonies was not significantly different between 2009 and 2010 as they could probably maintain their feeding in leads and cracks in the denser ice coverage in 2010.

The estimates presented here are corrected for both observer perception bias and availability bias: perception bias was addressed using a double-platform survey protocol and MRDS methodology; and availability bias was addressed by correcting the abundance estimates by the percentage of time animals were available for detection, either at the surface or hauled out. The small numbers of walruses and polar bears detected precluded the use of the MRDS model and so simpler estimators were used. MRDS models allow factors affecting detectability to be taken into account. The simpler estimators assume that detection is constant within the truncation distance which may not always be plausible and would therefore yield negatively biased results. The estimator for walrus assumed that detection was constant within a specified strip which, given the results indicating that the probability of detection of walrus in the water appeared to be constant to a distance of 300 m and walrus on ice are thought to be at least as detectable as walrus in the water, seems reasonable.

Reliable estimates of the availability bias factors are vitally important; if animals are only available for a short period of time the bias factors can substantially increase the abundance estimates. The availability correction factors used assume that the survey was instantaneous which is not strictly true as the animals will have to be within detectable range for more than an instant, thus this correction may yield somewhat positively biased results, although species-specific data that can address this problem are missing (see Electronic Supplementary Material). Chapman’s estimator (Chapman 1951) and the strip census estimation are likely to result in a negatively biased estimate of walrus numbers on the ice.

Previous aerial surveys of marine mammals in the North Water were conducted in March–April 1978, March 1979, and March 1993 (Finley and Renaud 1980; Richard et al. 1998), i.e., about 2 months earlier in the year than the 2009 and 2010 surveys. Those earlier surveys with much lower coverage were flown over very different sea ice conditions than prevailed during the present surveys. During all previous surveys, an ice bridge was present across Smith Sound from Ellesmere Island to Greenland, and pack ice with sheets of new ice covered the area south of the ice bridge. Occasional leads and cracks provided marine mammals their main access to open water and in the 1993 survey it was estimated that sea ice covered 90 % of the North Water (Richard et al. 1998). In a typical year, the ice bridge across Smith Sound would persist through June (Ingram et al. 2002). It was already obvious in January 2009 that the North Water was experiencing an unusually low rate of ice formation and that most of the ice generated in Smith Sound was being blown south out of the North Water area (GINR, unpublished data). Apparently, the increasing proportion of open water has been a persistent pattern in the North Water during the past decade. But the extreme within- and between-year variability in the extent of sea ice coverage prevents assignment of statistical significance to the observed declines in the North Water during the 30-year period with data. In the neighboring, and much larger, Baffin Bay region (668 000 km2) just south of the North Water (36 000 km2) sea ice conditions are more stable, the year-to-year variability is much smaller (Fig. 4b) and the decline in sea ice is substantial. It is likely that the North Water is subject to the same forces as those driving the recent loss of sea ice in Baffin Bay. Indeed, the loss of sea ice in nearly all regions of the Arctic is well documented (Perovich and Richter-Menge 2009), driven by long-term atmospheric warming in the Arctic at nearly twice the global average rate (IPCC 2007). In comparison in the North Water, the downward trend in sea ice coverage is somewhat masked by large interannual variability.

Walruses were observed in all three previous surveys but in low numbers in 1978 (36) and 1993 (13). In March 1979, a total of 700 walruses were counted in leads on the Canadian side of the North Water (Finley and Renaud 1980). Even though the numbers fluctuate widely it is obvious that the North Water appears to be an important area for walruses.

The narwhals summering in the North Water and adjacent waters presumably winter further south in Baffin Bay although the exact location, as well as timing of arrival in the North Water, is unknown (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2012). Few narwhals were detected in past winter surveys of the North Water (none in 1978, 12 in 1979, and 15 in 1993) and narwhals were clearly much more abundant in May 2009 and 2010. This is likely due to the spring migration of narwhals into the North Water region from Baffin Bay. Narwhals spend the summer in the fjords adjacent to the North Water and they are particularly abundant in Inglefield Bredning but can also be found further north in Smith Sound. The average abundance of narwhals in the North Water for the 2 years with surveys was 7726 (CV 0.38, 95 % CI 2032–8572) which is similar to an abundance estimate of the stock summering in Inglefield Bredning in 2007 (8368, CV 0.25, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2010). The whales observed south of Northumberland Island seemed to be heading toward the ice edge at the southern entrance (south of Qeqertarsuaq) of the summering ground in Inglefield Bredning. The narwhals in strata 7 and 8 and the northern part of stratum 9 (Fig. 5) apparently would have passed Inglefield Bredning, the main summering ground in the North Water, but it is uncertain whether these whales summer in the Smith Sound region or return to Inglefield Bredning.

Belugas were seen mainly in narrow leads and cracks on the Canadian side along Devon Island, in eastern Lancaster Sound and Jones Sound and in southern Smith Sound in all three winter surveys, although in 1993 they were also detected in the central part of the North Water. In March 1978, belugas (85) were detected on the Greenland side close to Northumberland Island. The total numbers of beluga sightings were 402 in 1978, 214 in 1979, and 733 in 1993, but these numbers are negatively biased due to partial coverage and the fact that no correction factors were applied to account for availability bias. These three winter surveys demonstrate that considerable numbers of belugas over-winter in the North Water as also confirmed by satellite tracking studies (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2003) and by the 2009–2010 spring surveys reported here. Whereas narwhals were heavily concentrated in stratum 9—the entrance to Inglefield Bredning—belugas were more uniformly distributed in the southern part of the North Water. It is generally assumed that most of the belugas that over-winter or occur in the North Water during the spring move to summering grounds in the Canadian high Arctic archipelago, with abundance increasing at the mouth of Lancaster Sound in May and June (Koski et al. 2002). Even though some belugas are seen occasionally in summer on the Greenland side of the North Water, there is no resident summer population there or along the east coast of Ellesmere Island. It is therefore most probable that belugas found in the North Water in May are on their way toward the Canadian summering grounds in the Canadian high Arctic (Koski et al. 2002), and that our 2009–2010 surveys were too late to capture the peak abundance of belugas. This is supported by the more southern distribution of belugas in the surveyed area and the generally southwest-ward swimming direction of these whales.

Bearded seals were previously reported along ice edges in the western part of the polynya (Finley and Renaud 1980) but in this study they were detected on ice floes or along the ice edges primarily over shallow water in the eastern part. The use of an availability correction factor developed for ringed seals is less than optimal and cause a bias of unknown direction for the bearded seal abundance estimate. The alternative of not applying a correction factor, however, certainly makes the bearded seal abundance estimate negatively biased.

The ringed and bearded seal abundance estimates represent only the hauled out population in the surveyed area. It is certainly negatively biased due to the low sighting rate over the large areas of open water where seals are hard to detect. Furthermore, the survey did not include the coastal fast-ice areas surrounding the North Water where a major part of the population occurs (Born et al. 2004). These are also the areas where most of the hunting of seals and polar bears occurs.

Bowhead whales were observed in the southern part of the North Water in 2010, which is in agreement with both historic and recent observations suggesting that the North Water is used by bowhead whales during winter and spring (Richard et al. 1998; Holst and Stirling 1999; GINR, unpublished data). Bowhead whales tagged with satellite transmitters in Disko Bay in May 2010 visited the southern part of the North Water at the time of the survey (GINR).

More than 30 million little auks and 300 000 guillemots are believed to breed on the Greenland side of the polynya (Egevang et al. 2003, http://www.natur.gl/pattedyr-og-fugle/fugle/polarlomvie/) and our survey demonstrated that the offshore distribution of the birds was concentrated on the Greenland side, with a more coastal distribution in 2009 than in 2010. In 2010, more ice was present in the southeastern part of the polynya than in 2009 and consequently the sea birds had to fly longer distances from the breeding sites to reach open water with their pelagic prey. No estimate of the eider population in the North Water is available and the survey only found them along the West Greenland coast. Average catches of sea birds during 1993–2010 was 37 087 little auks, 1479 guillemots and 97 eiders (Piniarneq 1993–2010).

The occurrence of marine mammals in the North Water deserves special attention for at least three reasons, as follows:

For millennia, air-breathing top predators have provided the basis for subsistence of a well-known maritime hunting culture, that of the paleo-Eskimos, the neo-Eskimos, and the present Inughuit, living along the coasts surrounding this productive polynya. The polynya offers the hunters early access to marine game animals at a critical time during the spring, when winter caches of food, fuel, and other staples are becoming exhausted. Ruins from many Paleo- and Neo-Eskimo structures are located along the North Water and the area has functioned as a gateway for several waves of migrants from the Canadian High Arctic to both East and West Greenland (Schledermann 1980, 1990). This movement was facilitated by the predictable occurrence of important marine resources like walruses, seals, and sea birds. Even today, large catches of marine mammals and sea birds are made in the Thule area (Table 4), and although other activities contribute to the economy, maritime hunting is considered essential to modern subsistence life in Northwest Greenland (Born 1987). Quotas for the harvest of marine mammals in the North Water are set by the Greenland Government (http://www.nanoq.gl) based on advice from the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources (polar bears), the Joint Commission for the Conservation and Management of Narwhal and Beluga (narwhals and belugas), and the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (walruses). No assessment of bearded seals has been conducted in the North Water but for ringed seals NAMMCO concluded in 1996 that catch levels probably were sustainable (NAMMCO 1996). To ensure sustainability current quotas (2012) restrict harvest levels slightly below past levels of exploitation (1993–2006).

The spring density of >1 marine mammal and ~600 seabirds per km2 in the open water part of the North Water is very high, at least compared to the densities of top predators in other high-latitude areas, incl. other polynias (Stirling 1980), and certainly compared to those in neighboring areas like Baffin Bay and Kane Basin to the south or north of the polynya. The concentration of top predators is supported by an exceptionally high level of primary production (up to 5.3 gCm−2 d−1), which rivals that reported for temperate and sub-arctic areas like the Bering Sea, the Dutch Wadden Sea, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, or Cheasapeake Bay (Klein et al. 2002). The primary production feeds the top predators through a short trophic web including copepods and polar cod (Boreogadus saida), and export to the benthic community is facilitated by fecal pellets, downward transport of organic material, and vertical migration of ice-associated organisms. Consistent with the core distribution of top predators, the primary production in the North Water is initiated in April (Mei et al. 2002) and reaches the highest values on the eastern side of the polynya in May (Klein et al. 2002). Apparently, the primary production is nutrient-limited, especially by nitrate depletion in the upper mixed layer (Tremblay et al. 2002). It is not fully understood how nutrients are being replaced within the euphotic zone but the abundant air-breathing top predators are a potential source through defecation (Roman and McCarthy 2010). At present it is not possible to quantify the amount of nutrients released at the surface as fecal material by air-breathing predators in the North Water. However, the large numbers of marine mammals, along with tens of millions of little auks and other seabirds, represent a potential source of nutrient cycling that could significantly enhance primary productivity in spring in the eastern part of the polynya.

The North Water is a climate-sensitive area and the decline in sea ice coverage since 2002 both there and in Baffin Bay more generally will, if continued, cause major changes in the use of the North Water by marine top predators. Perhaps even more important than the reduction in sea ice in a given month is the change in timing of sea ice recession to a particular threshold. For instance, the 50 % sea ice threshold arrived about 2 weeks earlier (on average) in the 2000s than in the 1980s. The timing of the sea ice retreat generally determines the initiation of primary production by allowing light to penetrate the upper water column and this has cascading effects on the food web. The timing of sea ice formation and recession plays a major role in triggering and shaping the trophic cascade in the North Water. The large colonies of guillemots rely on the strict schedule of primary production where the predictable peak offers reliable and abundant ice-related foraging opportunities when the birds arrive at their breeding colonies (Laidre et al. 2008). Sea ice is also an important substrate for the haul-out of seals and walruses and it provides predation opportunities for polar bears. Walruses and bearded seals use sea ice when feeding over shallow water, and the drift and dispersal of ice floes assists in preventing local depletion of benthic prey resources. Ringed seals feed on ice-associated prey and, like the other seals, use sea ice for moulting and whelping. Further reduction in sea ice will thus reduce the carrying capacity of this environment for the seals (cf. Sundqvist et al. 2012). The situation for narwhals and belugas may be less of a concern because they range more widely and sea ice is acting more like a barrier for their movements between feeding areas. Finally, there are recent indications that temperate-region marine mammals have started to use the North Water area in summer, e.g., observations of common minke whales (Balaenoptera acuturostrata) and humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). This trend could bring new competition to the high Arctic whales and seals that have traditionally used the North Water.

The North Water is a bellwether for some of the rapid changes that currently affect marine areas of the Arctic and there are good reasons for monitoring both physical (sea ice and circulation patterns) and biological (nutrient cycling and top predators) conditions in this uniquely productive high-latitude polynya. Declaration of this area as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve would be one way of recognizing its global significance and maintaining an international focus on monitoring its status.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and the National Environmental Protection Agency, Danish Ministry of Environment, under the program for cooperation on the environment in the Arctic (Dancea). Air Greenland operated the Twin Otter that was used for the survey. The Vetlessen Foundation provided funding for the Redhen Systems data recording equipment.

Biographies

Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen

is a Senior Scientist with the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources (GINR). He has been working in Greenland and other parts of the Arctic with ecological studies of whales, seals, and walruses for the past 30 years. He has pioneered new techniques for satellite tracking and surveys of Arctic animals.

Louise M. Burt

is a Research Fellow with the Centre for Research into Ecological and Environmental Modelling at the University of St Andrews. She is a specialist in line transect sampling and distance modelling.

Rikke Guldbo Hansen

is a Research Assistant with the GINR and is specialized in conducting and analysing aerial surveys of marine mammals.

Nynne Hjort Nielsen

is a Research Assistant with the GINR and is specialized in analysing data on diving behavior of whales.

Marianne Rasmussen

is an Associate Professor at the University of Iceland where she is particularly involved in ecological studies of cetaceans and studies of underwater acoustics.

Sabrina Fossette

is a Postdoctoral Researcher at Swansea University. She is specialized in biotelemetry studies of marine vertebrates (in particular sea turtles and marine mammals) and has many years of experience in surveys of whales in Greenland.

Harry Stern

is a Senior Mathematician at the Polar Science Center, University of Washington, Seattle, USA, where he studies Arctic sea ice and climate change using satellite data.

Contributor Information

Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen, Phone: +4540257943, FAX: +45-3283-3801, Email: mhj@ghsdk.dk.

Louise M. Burt, Phone: +44-01334-461805, Email: louise@mcs.st-and.ac.uk

Rikke Guldborg Hansen, Phone: +45-32833826, FAX: +45-3283-3801, Email: rgh@ghsdk.dk.

Nynne Hjort Nielsen, Phone: +45-32833826, FAX: +45-3283-3801, Email: nhn@ghsdk.dk.

Marianne Rasmussen, Phone: +354-4645120, Email: mhr@hi.is.

Sabrina Fossette, sabrina.fossette@googlemail.com.

Harry Stern, Phone: +206-543-7253, FAX: +206-616-3142, Email: harry@apl.washington.edu.

References

- Barber DG, Hanesiak JM, Chan W, Piwowar J. Sea-ice and meteorological conditions in northern Baffin Bay and the North Water polynya between 1979 and 1996. Atmosphere-Ocean. 2001;39:343–359. doi: 10.1080/07055900.2001.9649685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers DL, Laake JL, Southwell C, Paxton CGM. Accommodating unmodelled heterogeneity in double-observer distance sampling surveys. Biometrics. 2006;62:372–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born, E.W. 1987. Aspects of present-day maritime subsistence hunting in the Thule Area, Northwest Greenland. In Between Greenland and America, eds. L. Hacquebord and R. Vaughan, 109–132. The Netherlands: Arctic Centre, University of Groningen.

- Born EW, Teilmann J, Riget F. Haul-out activity of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) determined from satellite telemetry. Marine Mammal Science. 2002;18:167–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2002.tb01026.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Born EW, Teilmann J, Acquarone M, Riget F. Habitat use of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in the North Water area (North Baffin Bay) Arctic. 2004;57:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Buckland ST, Anderson DR, Burnham KP, Laake JL, Borchers DL, Thomas L. Introduction to distance sampling: Estimating abundance of biological populations. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri, D. C., C. Parkinson, P. Gloersen, and H. J. Zwally. 2010. Sea ice concentrations from Nimbus-7 SMMR and DMSP SSM/I passive microwave data, 1979–2010. Boulder: National Snow and Ice Data Center. Digital media.

- Chapman DG. Some properties of the hypergeometric distribution with applications to zoological censuses. University California Publications Statistics. 1951;1:131–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz R, Heide-Jørgensen MP. Movements and swimming speed of narwhals, Monodon monoceros, equipped with satellite transmitters in Melville Bay, Northwest Greenland. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 1995;73:2120–2132. doi: 10.1139/z95-248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, M. 1981. Physical causes and biological significance of polynyas and other open water in sea ice. In Polynyas in the Canadian Arctic, eds. I. Stirling and H. Cleator, 29–43. Occasional Paper Number 45. Canadian Wildlife Service.

- Egevang C, Boertman D, Mosbech A, Tamsdorf MP. Estimating colony area and population size of little auks Alle alle at Northumberland Island using aerial images. Polar Biology. 2003;26:8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Finley KJ, Renaud WE. Marine mammals inhabiting the Baffin Bay North Water in winter. Arctic. 1980;33:724–738. [Google Scholar]

- Heide-Jørgensen MP. Aerial digital photographic surveys of narwhals, Monodon monoceros in Northwest Greenland. Marine Mammal Science. 2004;20:58–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01154.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heide-Jørgensen MP, Acquarone M. Size and trends of the bowhead, beluga and narwhal stocks wintering off West Greenland. Scientific Publications of the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission. 2002;4:191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Heide-Jørgensen MP, Richard P, Dietz R, Laidre KL, Orr J. An estimate of the fraction of belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) in the Canadian High Arctic that winter in West Greenland. Polar Biology. 2003;23:318–326. [Google Scholar]

- Heide-Jørgensen MP, Laidre KL, Burt ML, Borchers DL, Margues TA, Hansen RG, Rasmussen M, Fossette S. Abundance of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) on the hunting grounds in Greenland. Journal of Mammalogy. 2010;91:1135–1151. doi: 10.1644/09-MAMM-A-198.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., P. Richard, R. Dietz, and K. Laidre. 2012. A metapopulation model for Canadian and West Greenland narwhals. Animal Conservation. doi:10.1111/acv.12000.

- Holst M, Stirling I. A note on sightings of bowhead whales in the North Water Polynya, Northern Baffin Bay, May–June, 1998. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 1999;1:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RG, Bacle J, Barber DG, Gratton Y, Melling H. An overview of the physical processes in the North Water. Deep-Sea Research II. 2002;49:4893–4906. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00169-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2007. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds. S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. B. Averyt, M. Tignor, and H. L. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 996 pp.

- Karnovsky NJ, Hobson KA, Iverson S, Hunt GL. Seasonal changes in diets of seabirds in the North Water Polynya: A multiple-indicator approach. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2008;357:291–299. doi: 10.3354/meps07295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, B., B. LeBlanc, Z.-P. Mei, R. Beret, J. Michaud, C.-J. Mundy, C.H. von Quillfeldt, M.E. Garneau, et al. 2002. Phytoplankton biomass, production and potential export in the North Water. Deep-Sea Research II 49: 4983–5002.

- Koski WR, Davis RA, Finley KJ. Distribution and abundance of Canadian High Arctic belugas, 1974–1979. Scientific Publications of the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission. 2002;4:87–126. [Google Scholar]

- Laake JL, Borchers DL. Methods for incomplete detection at zero distance. In: Buckland ST, Anderson DR, Burnham KP, Laake JL, Borchers DL, Thomas L, editors. Advanced distance sampling. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 108–189. [Google Scholar]

- Laidre KL, Heide-Jørgensen MP, Nyeland J, Mosbech A, Boertmann D. Latitudinal gradients in sea ice and primary production determine Arctic seabird colony size in Greenland. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2008;275:2695–2702. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerczak J, Hobbs RC. Calculating sighting distances from angular readings during shipboard, aerial, and shore-based marine mammal surveys. Marine Mammal Science. 1998;14:590–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1998.tb00745.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerczak JA, Hobbs RC. Errata. Marine Mammal Science. 1998;14:903. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1998.tb00745.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marques FFC, Buckland ST. Covariate models for the detection function. In: Buckland ST, Anderson DR, Burnham KP, Laake JL, Borchers DL, Thomas L, editors. Advanced distance sampling. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Z.-P., L. Legendre, Y. Gratton, J.-É. Tremblay, B. LeBlanc, C.-J. Mundy, B. Klein, M. Gosselin, et al. 2002. Physical control of spring-summer phytoplankton dynamics in the North Water, April–July 1998. Deep-Sea Research II 49: 4959–4982.

- NAMMCO. 1996. Report of the Scientific Committee. NAMMCO Annual Report 1996. http://www.nammco.no/webcronize/images/Nammco/746.pdf. Accessed 19 Nov 2012.

- NAMMCO. 2010. Stock status of walrus in Greenland and adjacent seas. North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission.http://www.nammco.no/webcronize/images/Nammco/983.pdf. Accessed 19 Nov 2012.

- Nielsen MR. Is climate change causing the increasing narwhal (Monodon monoceros) catches in Smith Sound, Greenland. Polar Research. 2009;28:238–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-8369.2009.00106.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perovich DK, Richter-Menge JA. Loss of sea ice in the Arctic. Annual Review of Marine Science. 2009;1:417–441. doi: 10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piniarneq. 1993–2010. Catch statistics for Greenland. Greenland Home Rule. www.nanoq.gl.

- Richard PR, Weaver R, Dueck L, Barber D. Distribution and numbers of Canadian High Arctic narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in August 1984. Meddelelser om Grønland, Bioscience. 1994;39:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Richard P, Orr JR, Dietz R, Dueck L. Sightings of belugas and other marine mammals in the North Water, Late March 1993. Arctic. 1998;51:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Roman J, McCarthy JJ. The whale pump: Marine mammals enhance primary productivity in a coastal basin. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schledermann P. Polynyas and prehistoric settlement patterns. Arctic. 1980;33:292–302. [Google Scholar]

- Schledermann P. Crossroads to Greenland (Komatik Series 2) Calgary: The Arctic Institute of North America; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling I. The biological importance of polynyas in the Canadian Arctic. Arctic. 1980;33:303–315. [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist, L., T. Harkonen, C.J. Svensson, and K.C. Harding. 2012. Linking climate trends to population dynamics in the Baltic ringed seal: Impacts of historical and future winter temperatures. AMBIO. doi:10.1007/s13280-012-0334-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tremblay J-É, Gratton Y, Fauchot J, Price NM. Climatic and oceanic forcing of new, net, and diatom production in the North Water. Deep-Sea Research II. 2002;49:4927–4946. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00171-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan R. Northwest Greenland. A history. Orono: The University of Maine Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.