Abstract

Purpose

To compare the clinical outcomes, complications, and surgical trauma between anterior and posterior approaches for the treatment of multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy.

Study design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases for randomized controlled trials or non-randomized controlled trials that compared anterior and posterior surgical approaches for the treatment of multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Exclusion criteria were non-controlled studies, combined anterior and posterior surgery, follow-up <1 year, cervical kyphosis >15°, and cervical myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. The main end points included: recovery rate; Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) score; reoperation rate; complication rate; blood loss; and operation time. Subgroup analysis was conducted according to the mean number of surgical segments.

Result

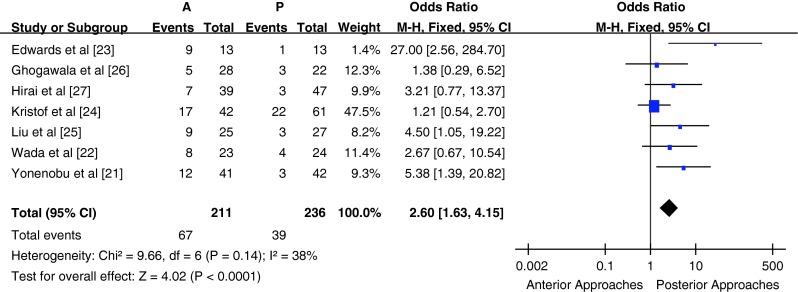

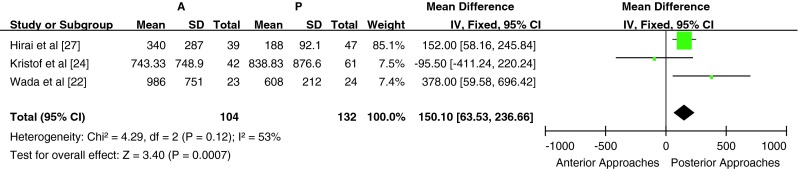

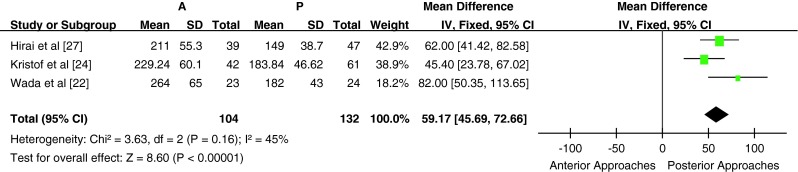

A total of eight studies were included in the meta-analysis; none of which were randomized controlled trials. All of the selected studies were of high quality as indicated by the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. In five studies involving 351 patients, the preoperative JOA score was similar between the anterior and posterior groups [P > 0.05, WMD: −0.00 (−0.56, 0.56)]. In four studies involving 268 patients, the postoperative JOA score was higher in the anterior group compared with the posterior group [P < 0.05, WMD: 0.79 (0.16, 1.42)]. For recovery rate, there was significant heterogeneity among the four studies involving 304 patients, hence, only descriptive analysis was performed. In seven studies involving 447 patients, the postoperative complication rate was significant higher in the anterior group compared with the posterior group [P < 0.05, odds ratio: 2.60 (1.63, 4.15)]. Of the 245 patients in the 8 studies who received anterior surgery, 21 (8.57 %) received reoperation. Of the 285 patients who received posterior surgery, only 1 (0.3 %) received reoperation. The reoperation rate was significantly higher in the anterior group compared with the posterior group (P < 0.001). In the 3 studies involving 236 patients compared subtotal corpectomy and laminoplasty/laminectomy, blood loss and operation time were significantly higher in the anterior subtotal corpectomy group compared with the posterior laminoplasty/laminectomy group [P < 0.05, WMD: 150.10 (63.53, 236.66) and P < 0.05, WMD: 59.17 (45.69, 72.66)].

Conclusion

The anterior approach was associated with better postoperative neural function than the posterior approach in the treatment of multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. There was no apparent difference in the neural function recovery rate. The complication and reoperation rates were significantly higher in the anterior group compared with the posterior group. The surgical trauma associated with corpectomy was significantly higher than that associated with laminoplasty/laminectomy.

Keywords: Anterior approach, Posterior approach, Cervical spondylotic myelopathy, Systemic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is the most common cause of myelopathy. The degeneration of the intervertebral disc and secondary degeneration of stable structures such as the uncovertebral joint, facet joint, posterior longitudinal ligament, and ligamentum flavum cause spinal cord compression and cervical myelopathy [1]. The presence of degenerative changes is very common in the general population and becomes more common with increasing age [2–4]. Individuals with congenital cervical canal stenosis are more vulnerable to cervical myelopathy caused by cervical degeneration and spinal cord compression [1–4].

The choice of surgical treatment for CSM remains controversial; however, most physicians agree that patients who have experienced symptoms for an extended period of time or who experience disease progression require surgical intervention [5, 6]. Generally, surgical approaches can be divided into anterior cervical canal decompression approaches and posterior cervical canal decompression approaches. Anterior cervical canal decompression approaches typically comprise corpectomy and anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF), whereas posterior cervical canal decompression approaches typically comprise laminoplasty and laminectomy.

For single-level CSM, ACDF is the gold standard. Indeed, several clinical case series’ have demonstrated >90 % fusion rates with satisfactory clinical results [7, 8]. However, for patients with CSM involving multiple segments associated with congenital cervical canal stenosis, the optimal surgical approach remains unclear.

Physicians who support the use of posterior decompression surgery believe that the surgical trauma and incidence of postoperative pseudarthrosis significantly increase with the number of involved segments when anterior surgical approaches are used [9, 10]. Findings from a recently published meta-analysis demonstrated that the fusion rate associated with the anterior procedure and plating was 97.1 % at the one-disc level, 94.6 % at the two-disc level, and 82.5 % at the three-disc level [11]. Anterior surgery also appears to be associated with a high rate of adjacent degeneration [12–14]. However, some authors have argued that although the adjacent degeneration rate is high with anterior cervical canal decompression approaches, it rarely leads to significant clinical symptoms or the need for reoperation [15, 16].

Physicians who support the use of anterior decompression surgery have expressed concern about the surgical trauma and high incidence of complications, such as axial pain and C5 root palsy, associated with posterior approaches [17, 18]. Further, some authors have suggested that patients who undergo posterior laminoplasty or laminectomy are more prone to develop cervical kyphosis or instability than those who receive treatment via anterior approaches [19].

Reports describing the advantages and disadvantages of anterior and posterior approaches for the treatment of multilevel CSM vary considerably; most are retrospective studies or single approach observational studies. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to compare the posterior approach with the anterior approach for the treatment of multilevel CSM.

End points of our analysis included: clinical outcome-related end points [recovery rate, Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) score, and Nurick grade]; complication-related end points (reoperation rate and complication rate); and operation-related end points (blood loss and operation time).

Methods

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) randomized or non-randomized controlled study; (2) included patients with CSM caused by multi-segmental spinal stenosis (≥2 segments); (3) included patients who underwent surgical treatment; (4) posterior cervical canal decompression and anterior cervical canal decompression were compared (regardless of the specific surgical approach); and (5) included patients >18 years of age.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they: (1) were non-controlled; (2) combined anterior and posterior surgery; (3) had an average follow-up time of <1 year; (4) included patients with cervical kyphosis >15°; (5) included patients with cervical myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). Studies involving patients with cervical kyphosis >15° were excluded because this is considered to be a contraindication for posterior surgery by many researchers [20]. Studies involving patients with cervical myelopathy caused by OPLL were excluded because this condition is different from CSM in terms of etiology, pathogenesis, and natural history; hence, this may have affected the surgeon’s decision making regarding the surgical approach used.

Search methods and selection of studies

We searched Ovid MEDLINE (1950-present), EMBASE (1980-present), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and bibliographies between May and July 2012. The search was not restricted to any specific language or by year of publication. The following search terms and strategies were used: (1) cervical myelopathy OR CSM OR myelopathy OR cervical spondylosis OR cervical vertebrae OR cervical stenosis; (2) Corpectomy OR ACDF OR anterior cervical discectomy and fusion OR anterior decompression and fusion OR anterior decompression OR ventral decompression OR ventral approach OR ventral; (3) laminoplasty OR laminectomy OR posterior decompression OR posterior decompression and fusion OR dorsal decompression OR dorsal approach OR dorsal; (1) and (2) or (3).

One reviewer conducted the initial search of all databases. Reviewers were not blinded to the authors, journal, or source of financial support. In stage one, two reviewers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts identified in the initial search according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In stage two, the full text of articles identified in stage one was reviewed. If additional data or clarification was necessary, we contacted the study authors. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion with three other reviewers.

Data extraction and management

The following information was collected from each study using a standardized form: (1) study ID; (2) study design; (3) study location; (4) main inclusion/exclusion criteria; (5) patient demographics; (6) length of follow-up; (7) number of surgical segments; (8) surgical approach for each group; (9) JOA scores before and after surgery; (10) recovery rate; (11) reoperation rate; (12) number of complications, type of complications, and rate of complications; and (13) operation time and blood loss.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was conducted according to the mean number of surgical segments; subgroup A included studies in which the mean number of surgical segments was between 2 and 3, whereas subgroup B included studies in which the mean number of surgical segments was more than 3.

Statistical analysis

Heterogeneity was tested using a Chi-square test, for which P < 0.1 was considered to be statistically significant. Inconsistency was quantified by calculating the I2 statistic. Continuous variables are presented as mean differences and 95 % confidence intervals, whereas dichotomous variables are presented as odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals. For the pooled effects, a weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated. Random-effects or fixed-effects models were used depending on the heterogeneity of the studies included. All statistical tests were performed using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Review Manager, version 5.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration).

Results

Search results

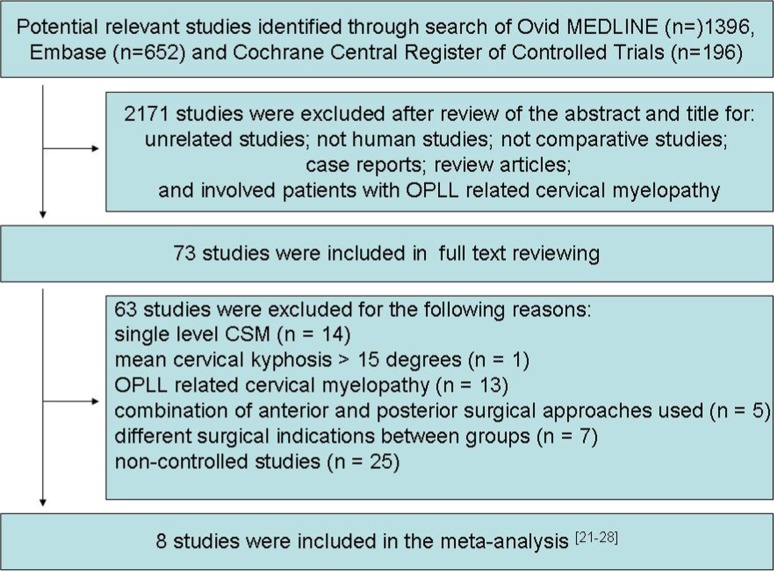

The initial search identified 1396 studies in Ovid MEDLINE, 652 studies in Embase, and 196 studies in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Of these studies, 2,171 were excluded after review of the abstract and title. The reasons for exclusion were as follows: unrelated studies; not human studies; not comparative studies; case reports; review articles; and involved patients with OPLL related cervical myelopathy. The remaining 73 studies underwent full text review. A further 65 studies were subsequently excluded for the following reasons: single level CSM (n = 14); mean cervical kyphosis >15° (n = 1); OPLL related cervical myelopathy (n = 13); combination of anterior and posterior surgical approaches used (n = 5); different surgical indications between groups (n = 7); and non-controlled studies (n = 25). Hence, a total of 8 studies were included in the meta-analysis [21–28]. The detail selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the study characteristics and outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Flow of studies through review

Table 1.

Common characteristics of included studies

| Study ID | Study design | Study location | Number of patients | Patient age statistics | Follow-up time | Surgical segments | Surgical approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yonenobu et al. [21] | Non-randomized Retrospective Comparative |

Japan | Total: 83 A: 41, P: 42 |

A: 56.0 ± 11.5 P: 54.3 ± 8.9 |

A: 53 months P: 43 months |

A: 2.51 P: 2.64 |

A: corpectomy with fusion P: laminoplasty |

| Wada et al. [22] | Non-randomized Retrospective Comparative |

Japan | Total: 47 A: 23, P: 24 |

A: 52.7 ± 7.6 P: 56.5 ± 11.2 |

A: 15 ± 2.7 years P: 11.7 ± 0.9 years |

A: 2.3 ± 0.7 P: 2.5 ± 0.8 |

A: corpectomy with fusion P: laminoplasty |

| Edwards et al. [23] | Non-randomized Retrospective Matched-cohort |

USA | Total: 26 A: 13, P: 13 |

A: 53 P: 54 |

A: 49 months P: 40 months |

A: 3.15 P: C3–C7 12 C4–C7 1 |

A: corpectomy with fixation and fusion P: laminoplasty |

| Kristof et al. [24] | Non-randomized Retrospective Comparative |

Germany | Total: 103 A: 42, P: 61 |

A: 62.5 ± 10.61 P: 66.0 ± 12.4 |

A: 196.56 ± 212.0 months P: 66.53 ± 34.21 months |

A: 2 P: 3 |

A: corpectomy and plate-screw-instrumented fusion P: laminectomy and rod-screw-instrumented fusion |

| Liu et al. [25] | Non-randomized Prospective Controlled |

China | Total: 52 A: 25, P: 27 |

A: 54.64 ± 11.49 P: 57.33 ± 10.09 |

A: 25.40 ± 13.76 (months) P: 27.47 ± 11.06 (months) |

A: 3.36 ± 0.57 P: 3.67 ± 0.55 |

A: ACDF with PCB system P: laminoplasty |

| Ghogawala et al. [26] | Non-randomized Prospective Pilot |

USA | Total: 50 A: 28, P: 22 |

A: 60 P: 64 |

1 year | A: 2.1 P: 3.1 |

A: multi-level of discectomy with fusion and fixation P: laminectomy with lateral mass fixation and fusion |

| Hirai et al. [27] | Non-randomized Prospective comparative |

Japan | Total: 86 A: 39, P: 47 |

A: 59.2 ± 10.7 P: 61.2 ± 10.1 |

5 years | A: 2.18 P: C3–7 27 C3–6 20 |

A: corpectomy with fusion and fixation P: laminoplasty |

| Shibuya et al. [28] | Non-randomized Retrospective Analysis of case series |

Japan | Total: 83 A: 34, P: 49 |

A: 60.4 ± 8.4 P: 64.8 ± 11.7 |

A: 11 years 11 months P: 8 years 3 months |

A: 3.18 P: 3.10 |

A: corpectomy with autologous bone grafting and halo-vest external fixation P: laminoplasty |

A anterior surgery group, P posterior surgery group

Table 2.

end points of studies included in this meta-analysis

| Study ID | JOA score | Recovery rate | Nurick grade | Complication | Reoperation rate and reason for reoperation | Blood loss, operation time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yonenobu et al. [21] | BO: A: 8.2 ± 2.2, P: 9.3 ± 3.0 PO: A: 13.3 ± 2.6, P: 12.8 ± 2.7 (final follow-up data) |

A: 44.9 ± 26.2 P: 55.3 ± 30.2 (final follow-up data) |

– | A: 12/41 29.3 % graft complications (10) esophageal fistula (1) retrolisthesis (1) P: 3/42 7.1 % C5 palsy(3) |

– | – |

| Wada et al. [22] | BO: A: 7.9 ± 1.8, P: 7.4 ± 2.2 1 year PO: A: 13.3 ± 1.6, P: 13.1 ± 2.0 5 years PO: A: 13.9 ± 2.0, P: 12.9 ± 2.3 Final PO: A: 13.4 ± 2.8, P: 12.2 ± 3.0 |

– | – | A: 8/23 34.8 % graft complication (7) esophageal fistula (1) P: 4/24 17 % C5 palsy (4) |

A: 7/23(6 for non-union of the graft and 1 for adjacent deterioration), P: 0 | A: 264 ± 65 min; 986 ± 751 g P: 182 ± 43 min; 608 ± 212 g |

| Edwards et al. [23] | – | – | BO: A: 1.9, P: 2.3 PO: A: 1.0, P: 0.8 | A: 9/13 69.2 % progression of myelopathy (1) pseudoarthrosis (1) subjacent ankylosis (1) persistent dysphagia (4) persistent dysphonia (2) P: 1/13 7.7 % radiculopathy(1) |

A: 0 P: 1/13(radiculopathy due to new disc herniation) |

A: 224 min; 572 ml P: 216 min; 360 ml |

| Kristof et al. [24] | – | – | BO: A: 3, P: 3 PO: A: 2, P: 2.5 | A: 40.4 % P: 36.0 % |

– | A: 229.24 ± 60.1 min; 743.33 ± 748.9 ml P: 183.84 ± 46.62 min; 839.83 ± 876.6 ml |

| Liu et al. [25] | BO: A: 8.16 ± 3.41P: 8.59 ± 2.98 PO: A: 13.20 ± 2.72P: 13.67 ± 2.70 |

A: 59.79 ± 23.43 % P: 59.54 ± 29.37 % |

– | A: 9/25 36.00 % late deterioration (2) screw loosening (1) pseudarthrosis (1) subjacent ankylosis (1) temporary odynophagia (2) temporary dysphonia(2) P: 3/27 11.11 % C5 root palsy (2) axial neck pain (1) |

A: 3/25(2 late deterioration and 1 screw loosening) P: 0/27 |

A: 115.92 ± 24.14 min; 118.48 ± 27.62 ml P: 187.78 ± 25.01 min; 361.11 ± 57.8 ml |

| Ghogawala et al. [26] | BO: A: 13.40 ± 0.44, P: 11.60 ± 0.5 PO: A: 15.44 ± 0.39, P: 13.54 ± 0.45 |

– | – | A: 5/28 (17.9 %) P: 3/22 (13.6 %) |

||

| Hirai et al. [27] | BO: A: 9.9 ± 3.1, P: 9.7 ± 2.9 1 year PO: A: 14.0 ± 2.6, P: 13.3 ± 2.5 2 years PO: A: 14.8 ± 2.0, P: 13.5 ± 2.5 3 years PO: A: 15.0 ± 2.3, P: 13.5 ± 2.6 5 years PO: A: 14.9 ± 2.3, P: 13.1 ± 2.9 |

1 year PO: A: 59.9 ± 27.4 %, P: 49.5 ± 25.8 % 2 years PO: A: 63.52 ± 28.6 %P: 50.4 ± 27.3 % 3 years PO: A: 74.1 ± 25.4 %, P: 52.5 ± 27.3 % 5 years PO: A: 72.9 ± 28.3 %, P: 50.2 ± 26.6 % |

– | A: 7/39 17.95 % airway problems (3) meralgia (2) C5 palsy (1) pseudoarthrosis (1) P: 3/47 6.38 % C5 palsy (3) |

A: 1/39(pseudoarthrosis) P: 0 |

A: 211 ± 55.3 min; 340 ± 287 ml P: 149 ± 38.7 min; 188 ± 92.1 ml |

| Shibuya et al. [28] | BO: A: 8.6 ± 2.9, P: 7.9 ± 2.4 | 1 years PO: A: 55.5 ± 25.3 %, P: 61.4 ± 21.2 % 5 years PO: A: 49.3 ± 29.3 %, P: 41.0 ± 26.6 % 12 years PO: A: 52.4 ± 28.1 %, P: 50.9 ± 25.9 % |

– | – | A: 10/34(6 for pseudoarthrosis and 4 for adjacent deterioration), P: 0 | A: 3-levels 1818 ± 1607 ml 2-levels 1292 ± 942 ml 1-level 662 ± 553 ml P: 404 ± 426 ml A: 3-levels 371 ± 89 min 2-levels 334 ± 73 min 1-level 265 ± 51 min P: 175 ± 60 min |

A anterior surgery group, P: posterior surgery group, BO before operation, PO post operation

Quality assessment of the studies

No randomized controlled trials were identified. All eight studies included were non-randomized controlled studies: five were retrospective studies and three were prospective studies. The major baseline characteristics of participants in each study (inclusion and exclusion criteria, demographics, preoperative JOA scores, surgical segments, and surgical procedures) were similar (Table 1). The quality of studies included was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale for non-randomized case controlled studies and cohort studies (www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm) [29]. Of the studies, seven scored 8 points and one scored 7 points; hence, the studies were of a relatively high quality (Table 3).

Table 3.

Quality assessment according to the Newcastle–Ottawa scale

Surgical approaches

The eight studies included a total of 530 patients; 245 who underwent anterior surgery, 192 who underwent corpectomy, and 53 who underwent multi-level discectomy with fusion and fixation. Of the 285 patients who underwent posterior surgery, 83 underwent laminectomy with fusion and fixation and 202 underwent laminoplasty.

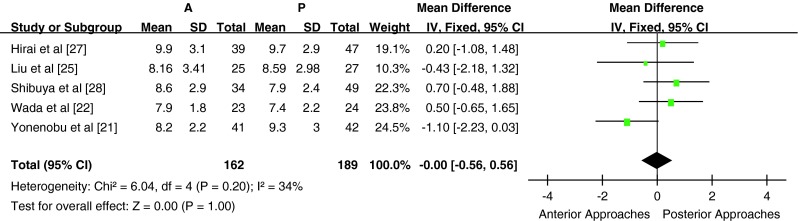

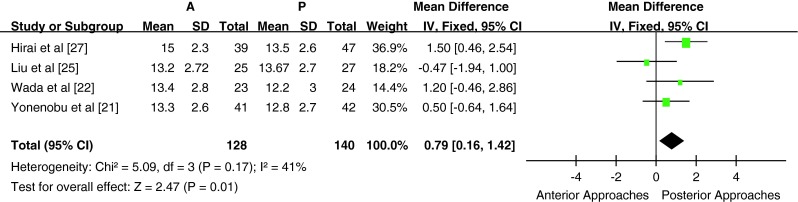

Clinical outcome

Five studies used the JOA score to assess the clinical outcome, all of which provided a preoperative JOA score (n = 351 patients; 162 in the anterior surgery group and 189 in posterior surgery group). The preoperative JOA score was similar between the two groups [P > 0.05, WMD = −0.00 (−0.56, 0.56); heterogeneity: χ2 = 6.04, df = 4, P = 0.20; I2 = 34 %, fixed-effects model, Fig. 2]. There was no significant difference in the preoperative JOA score between the anterior surgery group and the posterior group in either subgroup A [P > 0.05, WMD = −0.17 (−0.85, 0.51); heterogeneity: χ2 = 4.23, df = 2, P = 0.12; I2 = 53 %, fixed-effects model] or subgroup B [P > 0.05, WMD = 0.34 (−0.64, 1.32); heterogeneity: χ2 = 1.10, df = 1, P = 0.29; I2 = 9 %, fixed-effects model]. Four of five studies provided a postoperative (last follow-up) JOA score (n = 268 patients; 128 in the anterior surgery group and 140 in the posterior surgery group). The postoperative JOA score was significantly higher in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group [P < 0.05, WMD = 0.79 (0.16, 1.42); heterogeneity: χ2 = 5.09, df = 3, P = 0.17; I2 = 41 %, fixed-effects model, Figs. 3]. There was a significant difference in the postoperative JOA score between the anterior surgery group and the posterior group in subgroup A [P < 0.05, WMD = 1.07 (0.38, 1.77); heterogeneity: χ2 = 1.65, df = 2, P = 0.44; I2 = 0 %, fixed-effects model]. There was only one study in subgroup B; hence, meta-analysis could not be conducted.

Fig. 2.

Weight mean difference of preoperative JOA score between anterior surgery group and posterior surgery group

Fig. 3.

Weight mean difference of postoperative JOA score between anterior surgery group and posterior surgery group

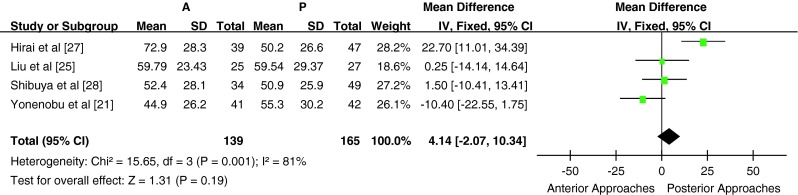

Four studies used recovery rate to assess the postoperative clinical outcome (n = 304 patients; 139 in the anterior surgery group and 165 in the posterior surgery group. There was significant heterogeneity between the studies (heterogeneity: χ2 = 15.65, df = 3, P = 0.001; I2 = 81 %, Fig. 4); therefore, meta-analysis could not be performed. There was significant heterogeneity among the groups in subgroup A (heterogeneity: χ2 = 14.80, df = 1, P = 0.0001; I2 = 93 %). In one study [27], the recovery rate was significantly higher in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group (72.9 ± 28.3 % vs 50.2 ± 26.6 %, P < 0.05). In the other study in subgroup A [21], the recovery rate was similar between the anterior and posterior surgery groups (44.9 ± 26.2 % vs 55.3 ± 30.2 %, P > 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference in recovery rate between the anterior and posterior surgery groups in subgroup B [P > 0.05, WMD = 0.99 (−8.18, 10.17); heterogeneity: χ2 = 0.02, df = 1, P = 0.90; I2 = 0 %, fixed-effects model]. Two studies used Nurick grade to assess the clinical outcome, but neither provided the standard deviation; hence, meta-analysis could not be performed.

Fig. 4.

Weight mean difference of recovery rate between anterior surgery group and posterior surgery group. There was significant heterogeneity between studies (χ2 = 15.65, P = 0.001, I2 = 81 %)

Complications and reoperation rate

The study records of postoperative complications were relatively inconsistent between studies and the definition of complications varied. Some studies provided all complications, whereas some provided the overall complications rate. Seven studies (n = 447 patients; 211 in the anterior surgery group and 236 in the posterior surgery group) provided a list of the postoperative complications or the incidence of postoperative complications (Table 1). The postoperative complication rate was significant higher in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group [P < 0.05, OR = 2.60 (1.63, 4.15); heterogeneity: χ2 = 9.66, df = 6, P = 0.14; I2 = 38 %, fixed-effects model, Fig. 5]. The postoperative complication rate was significantly higher in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group in subgroup A [P < 0.05, OR = 2.43 (1.49, 3.99); heterogeneity: χ2 = 8.91, df = 5, P = 0.11; I2 = 44 %, fixed-effects model]. Subgroup B comprised only one study; hence, meta-analysis could not be performed.

Fig. 5.

Odds ratio of complication rates between anterior surgery group and posterior surgery group

Of the 245 patients from 8 studies who received anterior surgery, 21 (8.57 %) required reoperation; 13 (61.9 %) for pseudoarthrosis/non-union of the graft; 7 (33.3 %) for adjacent deterioration; and 1 (4.8 %) for fixation loosening. Of the 285 patients who received posterior surgery, only 1 (0.3 %) required reoperation for radiculopathy due to new disc herniation. The reoperation rate was significantly higher in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group (P < 0.001).

Blood loss and operation time

Six studies reported the intraoperative blood loss and operation time; however, two of these studies were excluded from the meta-analysis (one did not provide the standard deviation of intraoperative blood loss and operation time, whereas the other only provided the blood loss and operation time for the subgroups). A total of 236 patients from 3 studies (104 patients in the anterior surgery group and 132 patients in the posterior surgery group) were included in the comparison of blood loss and operative time for subtotal corpectomy vs laminoplasty/laminectomy. Blood loss and operation time were significantly higher in the anterior subtotal corpectomy group compared with the posterior surgery laminectomy/laminoplasty group [P < 0.05, WMD = 150.10 (63.53, 236.66); heterogeneity: χ2 = 4.29, df = 2, P = 0.12; I2 = 53 %, fixed-effects model; and P < 0.05, WMD = 59.17 (45.69, 72.66); heterogeneity: χ2 = 3.63, df = 2, P = 0.16; I2 = 45 %, fixed-effects model, Figs. 6, 7]. All three studies were included in subgroup A; hence, subgroup analysis was not performed. One study, which compared blood loss and operation time for anterior multilevel discectomy and posterior laminoplasty, was not included in the meta-analysis.

Fig. 6.

Weight mean difference of intraoperative blood loss between anterior surgery group and posterior surgery group

Fig. 7.

Weight mean difference of operation time between anterior surgery group and posterior surgery group

Discussion

Several review articles have been published regarding decision making in the treatment of CSM [30, 31]. Cunningham et al. [30] published a systemic review of cohort studies comparing surgical treatment for CSM, including single segment CSM. In this article, the authors’ focused on comparing the clinical outcomes with different surgical approaches (ACDF, corpectomy, laminectomy and laminoplasty). The literature suggests that decision making in the treatment of multi-segmental CSM can be challenging for treating physicians. Blood loss, operation time, the incidence of postoperative adjacent degeneration, and the incidence of complications all increase significantly with the number of involved anterior surgical segments. Liu et al. [31] published a systemic review on surgical approaches (anterior or posterior) for multilevel myelopathy, including that caused by cervical spondylosis and OPLL. Over the last 2 years, a series of comparative studies on surgical approaches for the treatment of multilevel CSM have been published; therefore, we designed a systemic review and meta-analysis to compare surgical approaches (anterior or posterior) for the treatment of multilevel CSM.

Selection of the surgical approach for the treatment of multi-level CSM remains controversial. Ghogawala et al. [32] performed a study assessing eligibility for randomization to surgical approaches in the treatment of CSM. In the study, the authors sent 20 images associated with actual cases to 239 surgeons and asked the surgeons to provide demographic information, their preferred surgical approach, and eligibility for randomization for 10 cases. Of the 20 cases, 12 were considered to be potentially eligible for randomization. Although no RCT studies were included in our study, all selected studies were of high quality and the baseline variables (such as age, gender ratio, preoperative JOA score, surgical segments, and surgical procedures) were similar; hence, we considered the included studies to be comparable.

Two clinical outcome end points were selected in our meta-analysis. In the meta-analysis of JOA scores, there was no significant difference between the anterior surgery group and the posterior surgery group in preoperative JOA scores. Postoperative JOA scores were better in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group. Subgroup analysis was consistent with the overall analysis and the heterogeneity was low to median. These findings indicate that the two groups had similar baseline neural function, but that postoperative neural function condition was better in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group. However, meta-analysis of recovery rate, which reflects postoperative improvement in neural function condition (JOA scores), there was significant heterogeneity between groups (χ2 = 15.65, df = 3, P = 0.001; I2 = 81 %).

Subsequent subgroup analysis revealed low heterogeneity and no significant differences in subgroup B. In contrast, there was significant heterogeneity in the one study in subgroup A, with a significantly higher recovery rate in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior group (72.9 ± 28.3 % vs 50.2 ± 26.6 %, P < 0.05). In this article [27], the authors suggested that residual anterior compression of the spinal cord after LAMP was the cause of the lower recovery rate in the posterior surgery group. Interestingly, the recovery rate without residual anterior compression was similar between the posterior surgery and anterior surgery groups (P > 0.05). When this study was excluded, there was no significant difference in the recovery rate between the two groups (P > 0.05, WMD = −3.14 (−10.47, 4.18); heterogeneity: χ2 = 2.17, df = 2, P = 0.34; I2 = 8 %]. Although postoperative neural function condition was better in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group, there was no difference in the recovery rate. There seemed no difference of clinical effects between anterior approach and posterior approach for the treatment of multilevel CSM.

We selected the reoperation rate for descriptive analysis and the complication rate for meta-analysis in the evaluation of complication-related outcomes. In the meta-analysis of complication rate, we found a significantly higher incidence of complications in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group. Subgroup analysis findings were similar. This indicates that anterior approaches for the treatment of multilevel CSM are associated with a higher incidence of complications. Considering the most of the complications were pseudarthrosis or non-fusion on the anterior approaches, this seemed to be due to technical reasons and quality of the bone grafts. We also assessed reoperation rate as another complication-related measure. We found that the reoperation rate was significantly higher in the anterior surgery group compared with the posterior surgery group (P < 0.05). Although the indications for reoperation between studies were not the same, anterior approach for the treatment of multilevel CSM seemed to have a high risk of reoperation.

In the evaluation of surgical trauma, operation time and blood loss were selected for meta-analysis. We compared studies in which corpectomy was performed with studies in which laminoplasty/laminectomy was performed. Both overall and subgroup analyses revealed that blood loss and operation time were significantly higher in the corpectomy group compared with the laminoplasty/laminectomy group. This indicates that, in the treatment of multilevel CSM, the surgical trauma associated with corpectomy is higher than that associated with laminoplasty/laminectomy. Meta-analysis of surgical trauma between multilevel ACDF surgery and laminoplasty/laminectomy was not performed because only one relevant study was identified.

Our study has a number of limitations that warrant mention. Firstly, none of the studies included in the meta-analysis were RCTs. Secondly, there was variability among the studies in the choice of indicators to evaluate the postoperative clinical effect. This clearly reflects the lack of a gold standard outcome measure. Thirdly, most of the studies focused on the evaluation of neurological function improvement (i.e., JOA score and recovery rate), but neglected to evaluate overall quality of life using instruments such as the SF-36 scale and the HR-QOL scale. Finally, follow-up time varied between the studies and thus may have influenced our results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although the anterior approach was associated with better postoperative neural function than the posterior approach in the treatment of multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy, there was no apparent difference in the neural function recovery rate. The complication and reoperation rates were significantly higher in the anterior group compared with the posterior group. The surgical trauma associated with corpectomy was significantly higher than that associated with laminoplasty/laminectomy. The comparison of multilevel ACDF with laminoplasty/laminectomy requires further investigation.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Edwards CC, 2nd, Riew KD, Anderson PA, Hilibrand AS, Vaccaro AF. Cervical myelopathy. Current diagnostic and treatment strategies. Spine J. 2003;3(1):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S1529-9430(02)00566-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernhardt M, Hynes RA, Blume HW, et al. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:119–128. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson RJL, Caplan LR. Cervical spondylitic myelopathy. Neurol Clin. 1985;3:373–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogino H, Tada K, Okada K, et al. Canal diameter, anteroposterior compression ratio, and spondylotic myelopathy of the cervical spine. Spine. 1983;8:1–15. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guidetti B, Fortuna A. Long-term results of surgical treatment of myelopathy due to cervical spondylosis. J Neurosurg. 1969;30(6):714–721. doi: 10.3171/jns.1969.30.6.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witwer BP, Trost GR (2007) Cervical spondylosis: ventral or dorsal surgery. Neurosurgery 60(1 Supp1 1):S130–S136 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Zhang ZH, Yin H, Yang K, et al. Anterior intervertebral disc excision and bone grafting in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983;8(1):16–19. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emery SE, Bolesta MJ, Banks MA, Jones PK. Robinson anterior cervical fusion comparison of the standard and modified techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19(6):660–663. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199403001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riew KD, Sethi NS, Devney J, Goette K, Choi K. Complications of buttress plate stabilization of cervical corpectomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24(22):2404–2410. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunders RL, Pikus HJ, Ball P. Four-level cervical corpectomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23(22):2455–2461. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199811150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser JF, Hartl R. Anterior approaches to fusion of the cervical spine: a metaanalysis of fusion rates. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6(4):298–303. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartolomei JC, Theodore N, Sonntag VK (2005) Adjacent level degeneration after anterior cervical fusion: a clinical review. Neurosurg Clin N Am 16(4):575–587, v [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Yue WM, Brodner W, Highland TR. Long-term results after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with allograft and plating: a 5- to 11-year radiologic and clinical follow-up study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(19):2138–2144. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000180479.63092.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baba H, Furusawa N, Imura S, Kawahara N, Tsuchiya H, Tomita K. Late radiographic findings after anterior cervical fusion for spondylotic myeloradiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18(15):2167–2173. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilibrand AS, Carlson GD, Palumbo MA, Jones PK, Bohlman HH. Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(4):519–528. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199904000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JC, Liu L, Wen-Cheng H, et al. The incidence of adjacent segment disease requiring surgery after anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion: estimation using an 11-year comprehensive nationwide database in Taiwan. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(3):594–601. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318232d4f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosono N, Yonenobu K, Ono K. Neck and shoulder pain after laminoplasty. A noticeable complication. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21(17):1969–1973. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199609010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imagama S, Matsuyama Y, Yukawa Y, et al. C5 palsy after cervical laminoplasty: a multicentre study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(3):393–400. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B3.22786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasuoka S, Peterson HA, MacCarty CS. Incidence of spinal column deformity after multilevel laminectomy in children and adults. J Neurosurg. 1982;57(4):441–445. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.4.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura I, Shingu H, Nasu Y. Long-term follow-up of cervical spondylotic myelopathy treated by canal-expansive laminoplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(6):956–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yonenobu K, Hosono N, Iwasaki M, Asano M, Ono K. Laminoplasty versus subtotal corpectomy. A comparative study of results in multisegmental cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992;17(11):1281–1284. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wada E, Suzuki S, Kanazawa A, Matsuoka T, Miyamoto S, Yonenobu K. Subtotal corpectomy versus laminoplasty for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a long-term follow-up study over 10 years. Spine. 2001;26:1443–1448. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200107010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards CC, II, Heller JG, Murakami H. Corpectomy versus laminoplasty for multilevel cervical myelopathy: an independent matched-cohort analysis. Spine. 2002;27:1168–1175. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristof RA, Kiefer T, Thudium M, et al. Comparison of ventral corpectomy and plate-screw-instrumented fusion with dorsal laminectomy and rod-screw-instrumented fusion for treatment of at least two vertebral-level spondylotic cervical myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(12):1951–1956. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1110-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu T, Yang HL, Xu YZ, Qi RF, Guan HQ. ACDF with the PCB cage-plate system versus laminoplasty for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011;24(4):213–220. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3181e9f294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghogawala Z, Martin B, Benzel EC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of ventral vs dorsal surgery for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(3):622–630. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31820777cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirai T, Okawa A, Arai Y, et al. Middle-term results of a prospective comparative study of anterior decompression with fusion and posterior decompression with laminoplasty for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36(23):1940–1947. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181feeeb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shibuya S, Komatsubara S, Oka S, Kanda Y, Arima N, Yamamoto T. Differences between subtotal corpectomy and laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spinal Cord. 2010;48(3):214–220. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D. Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale for case control studies and cohort studies. www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm

- 30.Cunningham MR, Hershman S, Bendo J. Systematic review of cohort studies comparing surgical treatments for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35(5):537–543. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b204cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu T, Xu W, Cheng T, Yang HL. Anterior versus posterior surgery for multilevel cervical myelopathy, which one is better? A systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(2):224–235. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1486-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghogawala Z, Coumans JV, Benzel EC, Stabile LM, Barker FG II (2007) Ventral versus dorsal decompression for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: surgeons’ assessment of eligibility for randomization in a proposed randomized controlled trial: results of a survey of the Cervical Spine Research Society. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 32(4):429–436 [DOI] [PubMed]