Abstract

Background

Reduced bone mineral density (BMD) is a significant sequelae in children receiving chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Reduced BMD is associated with an increased risk for fractures. Pamidronate, a second-generation bisphosphonate, has been used to treat osteoporosis in children. This study evaluated the safety and efficacy of pamidronate in children with low BMD during and after chemotherapy for ALL and NHL.

Methods

Between April 2007 and October 2011, 24 children with ALL and NHL were treated with pamidronate. The indication was a decreased BMD Z-score less than -2.0 or bone pain with a BMD Z-score less than 0. Pamidronate was infused at 1 mg/kg/day for 3 days at 1-4 month intervals (pamidronate group, cases). The BMD Z-scores of the cases were compared with those of 10 untreated patients (control group). Lumbar spine BMDs were measured every 6 cycles using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and Z-scores were calculated. Bone turnover parameters (25-hydroxyvitamin D, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone, osteocalcin, and type I collagen c-terminal telopeptide) were analyzed.

Results

The median cycle of pamidronate treatment was 12. Increases in BMD Z-scores were significantly higher in the pamidronate group than in the control group (P<0.001). BMD (mg/cm2) increased in all pamidronate-treated cases. Twenty patients who complained of bone pain reported pain relief after therapy. The treatment was well tolerated.

Conclusion

Pamidronate appears to be safe and effective for the treatment of children with low BMD during and after chemotherapy for ALL and NHL.

Keywords: Pamidronate, Bone mineral density, Bisphosphonate, ALL, NHL, Corticosteroids

INTRODUCTION

As the number of childhood cancer survivors increases, concerns are increasing regarding the long-term complications and quality of life. In Korea, the current 5-year survival rate for childhood cancer patients under 14 years of age has significantly improved from the pre-1995 rate of 55% to the current rate of nearly 72% [1]. However, the late sequelae associated with childhood cancer and the required treatments are important concerns [2].

A decrease in bone mineral density (BMD) is a common consequence of treatments for cancers in children and adolescents [3]. The pathogenesis of decreased BMD in childhood cancer is multifactorial. Chemotherapy including glucocorticoids, methotrexate, and ifosfamide can affect bone formation. In addition, cancer therapies (e.g., irradiation and alkylating agents) that induce hypogonadism and growth hormone deficiencies can decrease the BMD. Decreased outdoor activity levels might induce decreased muscle mass and vitamin D deficiency as well as decreased BMD [4]. As a result of these multiple factors, many young cancer survivors have reduced BMD. This condition can lead to fractures, deformities, pain, and substantial financial burdens to both the patients' families and society.

Reduced BMD is a well-known treatment-associated complication in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [3]. ALL and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) are treated according to similar protocols. Reduced BMD is also frequent in adult NHL survivors, who receive different chemotherapy combinations [5]. Corticosteroids and methotrexate are important therapeutic components of treatment for ALL and NHL, and these agents have been shown to play an important role in the development of reduced BMD in ALL and NHL patients [3, 4].

Bisphosphonate compounds are potent bone resorption inhibitors that have been used to treat primary and secondary osteoporosis. Pamidronate, a second-generation agent of this pharmaceutical family, is the most widely used bisphosphonate in children and adolescents [6]. Pamidronate is reported to have beneficial effects in children with osteogenesis imperfecta [7, 8], fibrous bone dysplasia [9], cerebral palsy [10], and chronic nephropathy [11]. The beneficial effects of pamidronate on osteoporosis or osteopenia in children with ALL have been recently reported for cases, in which pamidronate was administered concurrently with chemotherapy [12, 13].

This study was performed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of pamidronate for BMD deficits in children that resulted from ALL and NHL treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

From January 2003 to August 2010, 231 children were diagnosed with cancer in the Division of Hemato-oncology, Department of Pediatrics at Yeungnam University Hospital. Among the 231 children, 105 underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanning. Calcium and vitamin D supplements were prescribed for 4 adolescent patients who were diagnosed with aseptic osteonecrosis (AON) of the long bones before the DXA evaluations. After DXA screening, 24 ALL and NHL patients received pamidronate therapy (pamidronate group). The indications for pamidronate therapy were a decreased BMD Z-score less than -2.0 or bone pain with a BMD Z-score less than 0 in the absence of hormonal deficiencies. Ten patients with normal Z-scores or no pain and low BMD Z-scores were classified as the control group and were evaluated for BMD at 6-month intervals. Four patients who failed to maintain BMD or complained of bone pain subsequently received pamidronate therapy and were analyzed in both the control and pamidronate groups.

Bone mineral density measurement

BMD of the lumbar spine (L1 to L4) was measured using DXA (Hologic Discovery, Bedford, MA, USA). BMD was expressed as mg/cm2. We used gender-specific and age-matched pediatric reference data from a previously published Korean normative dataset by Lee et al. [14]. The same DXA instrument was used in that study to calculate Z-scores for the lumbar spine. Z-scores were calculated using the following equation:

Pamidronate treatment protocol

Patients received intravenous (IV) pamidronate cycles at 1- to 4-month intervals. Each cycle consisted of a 6-hour IV infusion of pamidronate (1 mg/kg/day) on 3 consecutive days. Pamidronate was administered for a minimum of 6 cycles and a maximum of 30 cycles, according to the responses noted on the serial BMD assessments. Blood samples were collected every 6 cycles to evaluate the bone turnover parameters (e.g., 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25-OHD], alkaline phosphatase [ALP], intact-parathyroid hormone [intact-PTH], osteocalcin, and type I collagen c-terminal telopeptide [ICTP]). Serum calcium, phosphate, magnesium, ALP, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine levels were analyzed at each visit both before and after pamidronate infusion. 25-OHD was measured using chemiluminescent immunoassay. Intact-PTH, osteocalcin, and ICTP were measured using radioimmunoassays. Pamidronate was administered until the BMD normalized or bone pain was resolved.

Statistical analysis

A paired t-test was used to compare the baseline and follow-up values. Continuous variables between the groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and paired t-test. Differences in categorical factors were tested across the subgroups using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. P values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Science, version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yeungnam University Medical Center (IRB No. PCR 10-60). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient's guardian.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

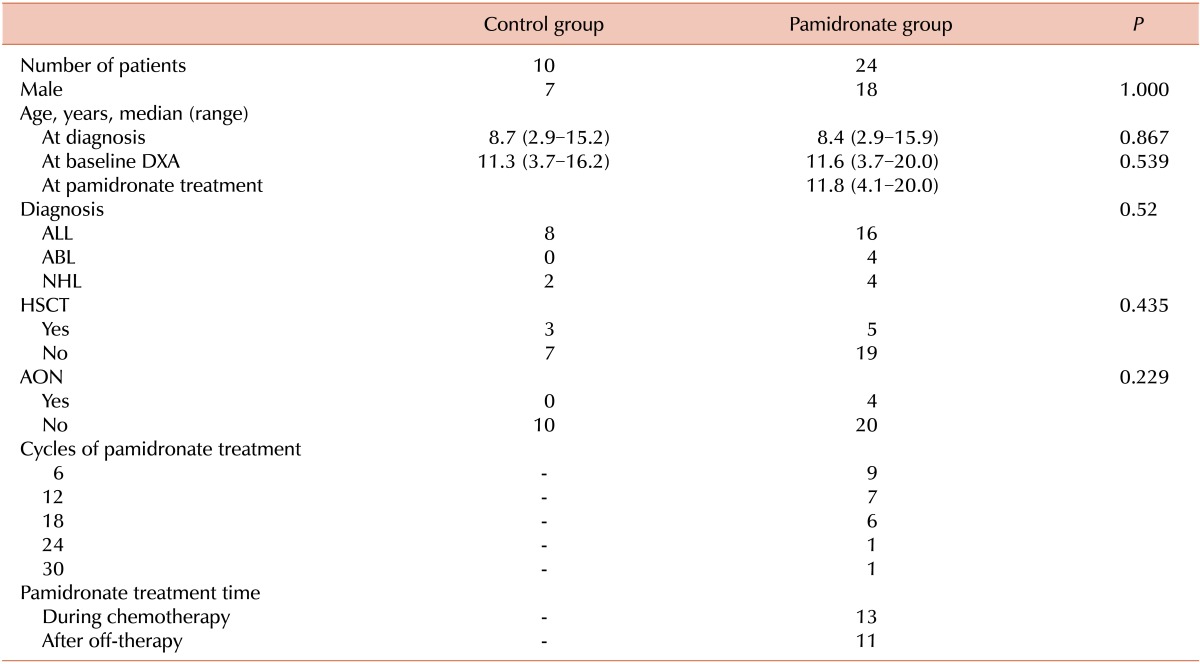

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In the pamidronate group, 5 patients underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and 4 patients had AON of the long bones before baseline DXA evaluations.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

P values were calculated using the chi-square or Fisher's exact test.

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; ABL, acute biphenotypic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; DXA, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; AON, aseptic osteonecrosis.

The median number of pamidronate therapy cycles was 12 (range, 6-30). One ALL patient who received 30 cycles of pamidronate therapy had multiple bone infarctions in the femurs and tibias at both knees. His baseline BMD Z-score was -4.3 (BMD 645 mg/cm2). After 30 cycles of pamidronate therapy, the follow-up BMD Z-score was -2.2 (BMD 781 mg/cm2).

Thirteen patients began pamidronate therapy during maintenance chemotherapy. Among them, 5 had low BMD Z-scores (less than -2.0). In the control group, 6 patients were evaluated for BMD during chemotherapy and 4 patients were evaluated after off-therapy.

Changes in BMD

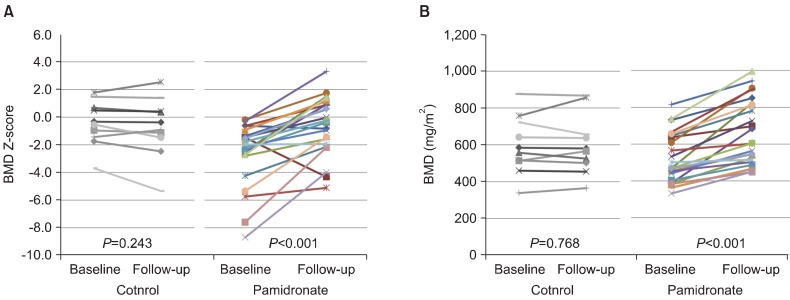

In the pamidronate group, the follow-up BMD Z-scores and lumbar spine BMDs (mg/cm2) increased after pamidronate therapy (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). However, in the control group, these scores did not change during the follow-up period (P=0.243 and P=0.768, respectively). In the pamidronate group, the BMDs of all 24 patients increased after pamidronate therapy, and 22 of the 24 patients had increased BMD Z-scores. Two patients who showed decreased BMD Z-scores despite receiving pamidronate therapy had AON before the pamidronate treatments. In the control group (N=10), 7 patients had decreased BMDs and 8 patients had decreased BMD Z-scores (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Changes in the bone mineral density (BMD) Z-scores. Graph shows the BMD Z-scores for each patient in the control and pamidronate groups at baseline and after follow-up. Eight of the 10 control group patients had decreased BMD Z-scores, and 22 of the 24 pamidronate group patients had increased BMD Z-scores. (B) Changes in BMD (mg/cm2). Graph shows the BMD for each patient in the control and pamidronate groups at baseline and after follow-up. The BMDs of all pamidronate group patients increased after pamidronate therapy; however, the BMDs of 8 control group patients (N=10) decreased.

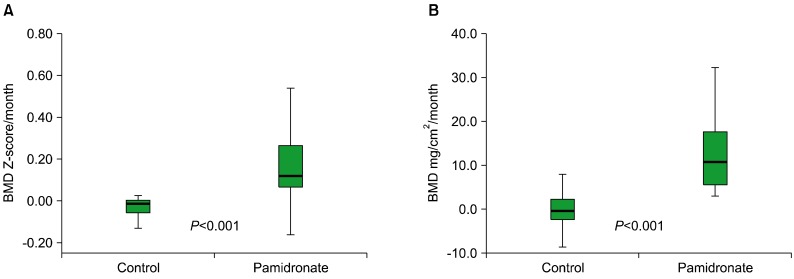

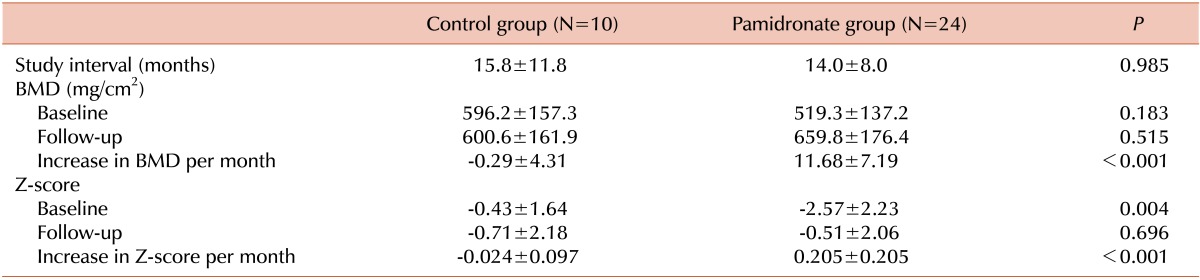

The median values of the increases in BMDs (mg/cm2/month) and BMD Z-scores (Z-score/month) were greater in the pamidronate group than in the control group (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively; Fig. 2). The increases in the BMDs (mg/cm2/month) and BMD Z-scores of the pamidronate group were +11.68±7.19 and 0.205±0.205 per month, respectively. However, those of the control group were -0.29±4.31 and -0.024±0.097 per month, respectively (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

(A) The monthly BMD Z-score increases in the control and pamidronate groups were -0.024±0.097 and +0.193±0.201, respectively (P<0.001). The median, 25th and 75th percentiles (box), and ranges of BMD changes (whiskers) are shown. (B) Changes in the BMD per month (mg/cm2/month) in the control and pamidronate groups were -0.29±4.31 and +11.92±6.98, respectively (P<0.001). The median, 25th and 75th percentiles (box), and ranges of the BMD changes (whiskers) are shown.

Table 2.

Pamidronate therapy outcomes.

Values are shown as the mean±SD.

Abbreviation: BMD, bone mineral density.

Before starting pamidronate therapy, 20 patients (83.3%) reported bone pain; all patients experienced improvements in bone pain after pamidronate treatment.

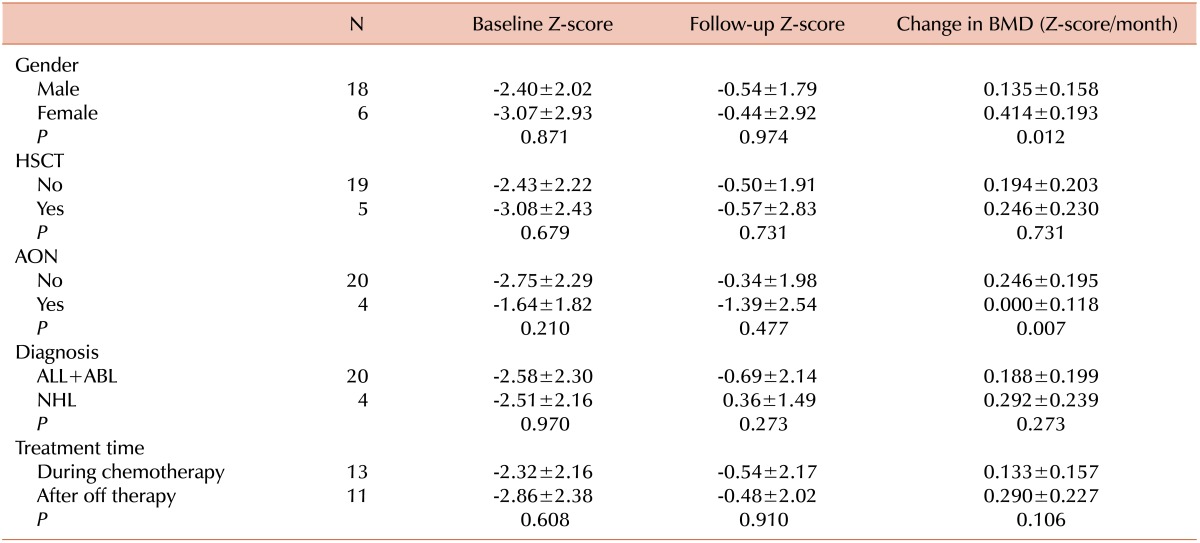

The baseline Z-scores did not differ according to sex, HSCT, AON, diagnosis, and pamidronate treatment time (Table 3). The baseline Z-scores were higher in patients with AON than in patients without AON. On the other hand, follow-up Z-scores were lower in patients with AON than in patients without AON. However, only changes in the BMD Z-scores were statistically significant. Male patients and patients with AON showed slower BMD Z-score increases. HSCT, diagnosis, and treatment times were not significant factors for changes in BMD Z-scores. No new cases of AON were noted among patients after starting pamidronate treatment.

Table 3.

Factors that affect bone mineral density and pamidronate treatment outcomes.

Values are shown as the mean±SD.

Abbreviations: HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; AON, aseptic osteonecrosis; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; ABL, acute biphenotypic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

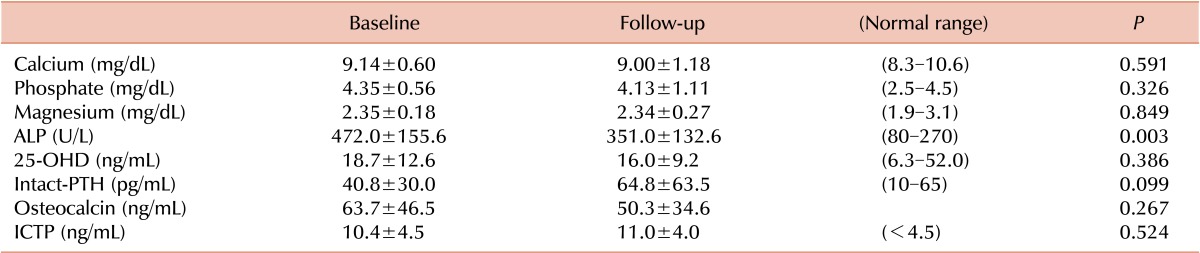

Laboratory findings

Changes in the laboratory test values are presented in Table 4. No significant changes were observed in the levels of biochemical markers, including calcium, phosphate, magnesium, 25-OHD, intact-PTH, osteocalcin, and ICTP. However, the ALP levels were significantly decreased after pamidronate treatment. The serum levels of ICTP and osteocalcin were above the normal ranges from the baseline measurements to the follow-up measurements after pamidronate treatment.

Table 4.

Changes in biochemical values after pamidronate treatment.

Values are shown as the mean±SD.

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; 25-OHD, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; PTH, parathyroid hormone; ICTP, type I collagen C-terminal telopeptide.

No changes in the levels of AST, ALT, BUN, or creatinine were noted either before or after pamidronate treatment.

Adverse reactions

The main adverse event was the onset of flu-like symptoms (e.g., fever and myalgia) within 24 hours after pamidronate infusion. This event occurred after 7 out of 300 administered cycles (2.3%) and was resolved in response to acetaminophen within a few hours. Another reported adverse event was mild symptomatic hypocalcemia with a tingling sensation in the hand (1 out of 300 infusions, 0.3%), which was resolved with oral calcium supplements.

DISCUSSION

Hogler et al. [15] reported that the 5-year incidence of skeletal complications during and after ALL treatment was 32.7% and that the relative risk of fractures, adjusted for age and gender, was 2.03 when compared to reference data from the UK General Practice Research Database. Survivors of childhood cancers are especially vulnerable to skeletal complications because they are affected during the period when peak bone mass should be achieved. Early treatments for bone loss is very beneficial in these children, since peak bone mass is attained during the adolescent years and provides a basis for bone strength and integrity in later life [11, 16].

Cyclic infusions of pamidronate are widely used as therapy for children with osteogenesis imperfecta [8] and secondary osteoporosis [6, 11]. Infusions of pamidronate at doses of 1-3 mg/kg every 1-4 months is a widely used therapy regimen for patients with osteogenesis imperfecta [7, 8, 17]. However, only a few available publications have reported the use of bisphosphonates in children with cancer.

In this study, children with low BMDs who received IV infusions of pamidronate during and after chemotherapy had increases in both lumbar spine BMDs and BMD Z-scores as well as decreases in bone pain. The results of this study are comparable to those of the pilot study by Barr et al. [12]. In that study, 10 children with ALL were treated with IV infusions of pamidronate, beginning on the first day of a maintenance chemotherapy cycle. The whole body bone mineral contents and lumbar spine BMDs of these patients were increased by 5-10% over the course of a 6-month study period. Goldbloom et al. [13] reported the use of pamidronate in 2 children with vertebral compression fractures at the time of ALL diagnosis; these patients received monthly 1 mg/kg pamidronate doses in addition to standard chemotherapy. Both patients experienced rapid pain relief and gradual improvements in BMD Z-scores. In clinical trials of osteosarcoma patients at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, IV pamidronate was safely incorporated with chemotherapy and did not impair the efficacy of chemotherapy [18].

Bisphosphonate inhibits osteoclast-mediated bone resorption in various ways, including the prevention of osteoclast formation, differentiation, and apoptosis induction [19]. Bisphosphonate may also prevent steroid-induced osteoporosis by protecting osteocytes and osteoblasts from corticosteroid-induced apoptosis [20]. Accordingly, pamidronate treatment during and after ALL maintenance chemotherapy might prevent steroid-induced osteoporosis.

Among patients who receive ALL therapy, AON is a well-recognized complication in the midst of childhood. Administration of corticosteroids, especially dexamethasone, has been the main etiologic factor for AON. Risk factors include an older age at diagnosis and radiation therapy [21]. There are few reports on the use of bisphosphonates for the treatment of AON in childhood hematologic malignancies. Pamidronate treatment seems to improve pain, musculoskeletal function, and daily activity. However, the objective radiologic benefit of pamidronate treatment is controversial [22, 23]. Four adolescent patients in this study had AON of the long bones (femurs and tibia). Three of the patients had ALL and 1 had NHL and received HSCT. These patients had slower increases in the monthly Z-scores than did non-AON patients (0.000±0.118 vs. 0.246±0.195, respectively; P=0.007). All 4 AON patients showed improvement in pain within 6 months and increases in BMDs after pamidronate treatment, but 2 of them showed decreased BMD Z-scores.

Serum ALP levels decreased during pamidronate treatment. ALP, a plasma membrane enzyme, has been used as a marker of bone formation [24]. In metabolic bone diseases such as Paget's disease, osteomalacia, and renal osteodystrophy, total serum ALP levels have been used to monitor disease activity [25]. Decreased serum ALP levels indicate decreased bone turnover during pamidronate treatment. Therefore, ALP can be a useful marker for monitoring responses to pamidronate treatment. Osteocalcin is produced by osteoblasts and is a sensitive marker of bone formation as ALP. Increased osteocalcin levels reflect increased bone turnover [24]. In this study, the mean osteocalcin levels decreased during pamidronate treatment; however, this change was not statistically significant.

PTH secretion is sensitive to serum calcium levels, and decreased serum ionized calcium levels lead to increased PTH levels. The dose-response curve is sigmoid shaped. PTH secretion dramatically increases when serum calcium levels decrease below 9 mg/dL. The plasma calcium PTH secretion system is designed to respond more dramatically to hypocalcemia than to hypercalcemia [26]. It is assumed that because of these 2 reasons, the degree of PTH increase is higher than that of calcium decrease. Serum ICTP is a marker of bone resorption, reflects the degradation of collagen type I in various bone pathologies, and is inversely correlated with BMD [24]. The high serum ICTP levels did not change during pamidronate treatment. It can be assumed that increased bone turnover is sustained during pamidronate treatment.

Cyclic pamidronate treatment was well tolerated. Seven episodes of flu-like symptoms occurred during the patients' first exposures; these episodes were resolved with acetaminophen. One episode of mild symptomatic hypocalcemia with a tingling sensation in the hand was resolved with calcium supplements. These episodes did not prohibit further dosing.

There were no serious complications, such as osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), in this study. In adults, ONJ is a well-recognized and potentially serious complication of bisphosphonate therapy [27]. Several risk factors for ONJ development have been identified, including periodontal disease, prior history of a dental procedure, exposure duration, bisphosphonate type, and older age [28]. However, there have been no reported cases of ONJ in children. A safe duration of pamidronate therapy has not yet been established for children. However, many studies of pamidronate treatment in children with osteogenesis imperfecta showed that long exposure to bisphosphonate, even exceeding 10 years, was considered safe.

In a recent report, oral alendronate was tolerated in pediatric patients and was suggested to have a positive effect on secondary osteoporosis [29]. However, there are practical limitations in small children; these include the need to administer alendronate after an overnight fast, at least 60 minutes before breakfast, and with at least 100 cc of water, and the requirement that the patient sit or stand for 30 minutes after swallowing alendronate to prevent esophagitis. This makes parenteral pamidronate infusion a preferred therapy over oral alendronate. Zoledronate is a newer and more potent bisphosphonate than pamidronate. In large clinical trials of zoledronate in adult cancer patients, this drug was more effective than pamidronate in reducing the risk of skeletal complication development, and the 2 drugs were associated with similar adverse events [30]. However, there are limited data on the use of zoledronate for secondary osteoporosis in children.

The long-term effects of pamidronate on the growing bones of cancer patients are unknown. The limitations of this study are that it was not a randomized trial and that the follow-up duration was short. In addition, the etiologies of BMD deficits in patients with childhood cancer other than the administration of steroids such as methotrexate, cranial irradiation, and hormonal dysfunction were not analyzed in depth because of the limited number of patients.

In conclusion, cyclic pamidronate therapy for low BMD during and after chemotherapy in children with ALL and NHL appears to be safe and effective. Further studies on a larger population are needed to establish the long-term effects and safety.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs. Annual report of cancer incidence (2007), cancer prevalence (2007) and survival (1993-2007) in Korea. Seoul, Korea: Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Sluis IM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Osteoporosis in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(2 Suppl):474–478. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasilewski-Masker K, Kaste SC, Hudson MM, Esiashvili N, Mattano LA, Meacham LR. Bone mineral density deficits in survivors of childhood cancer: long-term follow-up guidelines and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e705–e713. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benmiloud S, Steffens M, Beauloye V, et al. Long-term effects on bone mineral density of different therapeutic schemes for acute lymphoblastic leukemia or non-Hodgkin lymphoma during childhood. Horm Res Paediatr. 2010;74:241–250. doi: 10.1159/000313397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianchi ML. How to manage osteoporosis in children. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19:991–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glorieux FH, Bishop NJ, Plotkin H, Chabot G, Lanoue G, Travers R. Cyclic administration of pamidronate in children with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:947–952. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810013391402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rauch F, Plotkin H, Travers R, Zeitlin L, Glorieux FH. Osteogenesis imperfecta types I, III, and IV: effect of pamidronate therapy on bone and mineral metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:986–992. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapurlat RD, Hugueny P, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ. Treatment of fibrous dysplasia of bone with intravenous pamidronate: long-term effectiveness and evaluation of predictors of response to treatment. Bone. 2004;35:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson RC, Lark RK, Kecskemethy HH, Miller F, Harcke HT, Bachrach SJ. Bisphosphonates to treat osteopenia in children with quadriplegic cerebral palsy: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Pediatr. 2002;141:644–651. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.128207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SD, Cho BS. Pamidronate therapy for preventing steroid-induced osteoporosis in children with nephropathy. Nephron Clin Pract. 2006;102:c81–c87. doi: 10.1159/000089664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barr RD, Guo CY, Wiernikowski J, Webber C, Wright M, Atkinson S. Osteopenia in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a pilot study of amelioration with pamidronate. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;39:44–46. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldbloom EB, Cummings EA, Yhap M. Osteoporosis at presentation of childhood ALL: management with pamidronate. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;22:543–550. doi: 10.1080/08880010500198285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Desai SS, Shetty G, et al. Bone mineral density of proximal femur and spine in Korean children between 2 and 18 years of age. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25:423–430. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Högler W, Wehl G, van Staa T, Meister B, Klein-Franke A, Kropshofer G. Incidence of skeletal complications during treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: comparison of fracture risk with the General Practice Research Database. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:21–27. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haddy TB, Mosher RB, Reaman GH. Osteoporosis in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncologist. 2001;6:278–285. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-3-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi JH, Shin YL, Yoo HW. Short-term efficacy of monthly pamidronate infusion in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:209–212. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyers PA, Healey JH, Chou AJ, et al. Addition of pamidronate to chemotherapy for the treatment of osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2011;117:1736–1744. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell RG. Bisphosphonates: mode of action and pharmacology. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 2):S150–S162. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2023H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plotkin LI, Weinstein RS, Parfitt AM, Roberson PK, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. Prevention of osteocyte and osteoblast apoptosis by bisphosphonates and calcitonin. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1363–1374. doi: 10.1172/JCI6800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadan-Lottick NS, Dinu I, Wasilewski-Masker K, et al. Osteonecrosis in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3038–3045. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotecha RS, Powers N, Lee SJ, Murray KJ, Carter T, Cole C. Use of bisphosphonates for the treatment of osteonecrosis as a complication of therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:934–940. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greggio NA, Pillon M, Varotto E, et al. Short-term bisphosphonate therapy could ameliorate osteonecrosis: a complication in childhood hematologic malignancies. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010:206132. doi: 10.1155/2010/206132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swaminathan R. Biochemical markers of bone turnover. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;313:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calvo MS, Eyre DR, Gundberg CM. Molecular basis and clinical application of biological markers of bone turnover. Endocr Rev. 1996;17:333–368. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-4-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, editors. Williams textbook of endocrinology: Expert consult. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011. pp. 1239–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van den Wyngaert T, Huizing MT, Vermorken JB. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw: cause and effect or a post hoc fallacy? Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1197–1204. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehrotra B, Ruggiero S. Bisphosphonate complications including osteonecrosis of the jaw. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006:356–360. 515. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bianchi ML, Cimaz R, Bardare M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alendronate for the treatment of osteoporosis in diffuse connective tissue diseases in children: a prospective multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1960–1966. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1960::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen LS, Gordon D, Kaminski M, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid compared with pamidronate disodium in the treatment of skeletal complications in patients with advanced multiple myeloma or breast carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, comparative trial. Cancer. 2003;98:1735–1744. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]