Abstract

Aim:

To compare the efficacy of garlic extract with 2% chlorhexidine (CHX) and calcium hydroxide Ca(OH)2 in disinfection of dentinal tubules contaminated with Enterococcus faecalis by using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Materials and Methods:

Agar diffusion test was done to evaluate the minimum inhibitory concentration of garlic extract against E. faecalis. Forty human extracted mandibular premolar teeth were selected for this study, access cavity was prepared and cleaning and shaping was done. Middle third of the root was cut using a rotary diamond disc. The teeth specimens were inoculated with E. faecalis for 21 days. Specimens were divided into four groups---Group 1: 2% CHX, Group 2: Garlic extract, Group 3: Ca(OH)2, and Group 4: Saline (negative control). The intracanal medicaments were packed inside the tooth specimens and incubated for 5 days. The dentinal chips were collected at 400 μm depth using a Gates-Glidden drill, following which DNA isolation was done. The specimens were analyzed using real-time PCR. The results were then statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by post hoc Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) multiple comparison of means.

Results:

Threshold cycle (Ct) values of 2% CHX was found to be 32.4, garlic extract to be 27.5, and Ca(OH)2 to be 25.6.

Conclusion:

A total of 2% CHX showed the maximum efficacy against E. faecalis, followed by garlic extract and Ca(OH)2.

Keywords: Calcium hydroxide, dentinal tubules, garlic extract, intracanal medicament, real- time polymerase chain reaction 2% CHX

INTRODUCTION

Etiology of pulpal necrosis and periapical pathosis is mainly due to bacteria and their products. Eliminating the microorganisms within the pulp space is a critical and important objective in treating a tooth with apical periodontitis.[1] Studies have shown that recurrent root canal infections can occur even after endodontic treatment and are most commonly associated with Enterococcus faecalis, the predominant Enterococcus species.[2,3] E. faecalis can resist routine endodontic disinfectants and can also survive the nutrient-deprived conditions in the root filled tooth.[4] They also have the capacity to form a biofilm on the dentine.[5,6]

Retention of microorganisms in dentinal tubules leads to persistent endodontic infections.[7] Mechanical instrumentation leaves portions of the root canal untouched. Due to complex anatomy of the root canal, mechanical instrumentation alone does not result in complete disinfection.[8] Reduction of the remaining bacteria, after chemomechanical instrumentation can be brought about by intracanal medicaments and can provide an environment conducive to periapical tissue repair. Hence, the intracanal medicament plays a key role in the success of root canal treatment.[9]

As it possesses bactericidal properties, Ca(OH)2 has been advocated as an intracanal medicament.[10] It can destroy bacterial cell membranes and the protein structure due to its high pH (of about 12.5).[11] 2% chlorhexidine (CHX) has been used as an intracanal medicament in endodontics.[12,13] CHX is a bis-bi-guanide. It adsorbs onto the cell wall of microorganism and causes leakage of intracellular components. CHX is active against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.[14]

In a previous study, the antimicrobial activity of 2% CHX, propolis, morinda citrifolia juice (MCJ), 2% povidone iodine (POV-I), and calcium hydroxide on E. faecalis-infected root canal dentine at two different depths (200 and 400 μm) at three time intervals (days 1, 3, and 5) was investigated. The results have shown that 2% CHX produced better antimicrobial efficacy followed by 2% POV-I, propolis, MCJ, and calcium hydroxide. There was no significant difference between propolis and MCJ.[15]

Garlic (Allium sativum L) has been found to have several pharmacological properties such as antimicrobial,[16] antiplatelet, antithrombotic,[17] and anticancer[18] activity. Historically, Louis Pasteur used garlic extract to treat infections.[19] Some of the common organisms inhibited by garlic and its derivatives include Streptococcus mutans,[20] Staphylococcus aureus,[21] and Escherichia coli.[21] So far, no study has been conducted to evaluate the antibacterial efficacy of garlic extract against E. faecalis. Hence, the aim of our study was to compare the efficacy of the garlic extract with 2% CHX and Ca(OH)2 in disinfection of dentinal tubules contaminated with E. faecalis by using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The research proposal was submitted to review by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Sri Ramachandra University, India and the study was approved (Ref: CSP/11/AUG/17/32).

Garlic extract preparation

Fresh garlic was washed and prepared for extraction. A total of 100 g of cleaned garlic bulbs and 125 mL of distilled water was added to a juicer and crushed. The mixture was filtered using a double filter paper and the supernatant was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. Final concentration of garlic extract filtrate, in solution was found to be 249 mg/mL. It was stored at -20°C until required.[22]

Agar diffusion test

An agar diffusion test was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar using the well diffusion method. Mueller-Hinton agar was freshly prepared after which, the surface was inoculated with 0.2 mL of brain heart infusion (BHI) broth culture of E. faecalis strain ATCC 29212. Four wells, 5 mm in diameter and 4 mm in depth were punched in the agar. To each one of these wells 25, 50, 100 μg of garlic extract, preparation of which has been mentioned above, was added. Plates were left to incubate for 24 h at 37°C. Agar dilution testing (25, 50, and 100 μg) was conducted in accordance with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standards using a garlic extract preparation as mentioned above.[23] Zones of inhibition at 25 μg was found to be 7.3 mm, 50 μg was found to be 7.9 mm, and 100 μg was found to be 10 mm. IC50 MIC concentration was found to be 31.25 μg/mL and IC90 MBC concentration was found to be 312 μg/mL.

Preparation of dentine specimens

Forty freshly extracted single-rooted human mandibular premolar teeth for orthodontic reasons, were selected for this study, access cavity was prepared, and cleaning and shaping was done. A rotary diamond disc was used to decoronate the teeth below the cemento enamel junction and the apical part of the root, to obtain 6 mm of the middle third of the root. Cementum was removed from the root surface. Gates Glidden Drills No 3 (Mani Inc, Tachigi-ken, Japan) was used to standardize the internal diameter of the root canals. Smear layer was removed using an ultrasonic bath of 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 5 min, followed by 3% NaOCl for 5 min to remove the organic and inorganic debris. The teeth were immersed in ultrasonic bath of distilled water for 10 min to remove trace chemicals. The specimens were autoclaved for 20 min at 121°C.[15]

Contamination of specimens

The test organism used for this study was E. faecalis. E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) was grown in tryptone soya agar for 24 h. The culture was suspended in 5 mL of Tryptic soy broth (TSB) and incubated for 4 h at 37°C and its turbidity adjusted to 0.5 McFarland Standard. Each dentine block was placed in a presterilized microcentrifuge tubes containing 1 mL of the TSB. A total of 50 μL of the inoculums containing the E. faecalis was transferred into each of the microcentrifuge tubes. At the end of 24 h, the dentine specimens were transferred into the fresh broth containing E. faecalis. All procedures were carried out under laminar flow. Purity of the culture was checked by subculturing 5 μL of the broth from the incubated dentine specimens in TSB on tryptone soya agar plates. Contamination of the dentine specimens using E. faecalis was carried out for a period of 21 days at 37°C.[15]

Antimicrobial assesment

At the end of 21 days, the blocks were irrigated with 5 mL of sterile water to remove the inoculated broth. Blocks were assigned into four groups-Group 1: 2% CHX (Asep-RC Anabond Stedman Pharma Research, Adyar, Chennai, India); Group 2: Garlic extract (312 μg/mL); Group 3: Ca(OH)2, Group 4: Saline (negative control). Methyl cellulose was used as a thickening agent for Groups 1, 2, and 4. Ca(OH)2 was mixed with saline in the ratio 1.5:1 by volume, to obtain the desired consistency. The medicaments were placed inside the root canal. The canals were then sealed at both the ends with paraffin wax and incubated at 37°C in an anerobic environment for 5 days. After 5 days, the harvesting of dentine was carried out at 400 μm depth with a sterile Gates-Gliden drill no. 5.[15]

DNA isolation

Lysozyme enzyme solution was prepared containing Tris HCl, EDTA, tritonex, lysozyme (20 mg per sample). To the dentine harvest samples, 1 mL of the above prepared solution was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a water bath. Next, 20 μL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate was added to the sample and again incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the bath. After incubation, an equal volume of phenol chloroform solution was added and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and transferred into new Eppendorf tubes, Chloro-iso-amine alcohol of equal volume was added and the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and transferred into a new Eppondorf tube, 1/10th the volume of sodium acetate and 300 μL of 100% ethanol (absolute) was added and stored at -50°C over night. The following day, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and discarded and the pellet was air dried. A total of 30-50 μLof distilled water were added (RNA/DNAase-free water).[24]

Real-time PCR

The reaction mix was prepared to a final volume of 20 μL and loaded in an optical 96 well plate, which was then covered with an optical adhesive sheet. E. faecalis was identified using PCR amplification of 16S rRNA gene sequences. The oligonucleotide species-specific primers (Bangalore Genei, India) for E. faecalis were 5¢GTT TAT GCC GCA TGG CAT AAG AG3¢ (forward primer, located at base position 165-187 of the E. faecalis 16S rDNA) and 5¢CCG TCA GGG GAC GTT CAG¢3 (reverse primer, located at base position 457-474 of the E. faecalis 16S rDNA). The PCR amplicon length was 310 bp. The samples were run in duplicate. Real-time PCR was performed using a thermal cycler (7900 HT RT-PCR, Applied Biosystem, UK) with SYBR green fluorophore. Reactions were run in a total volume of 20 μL including 10 μL of SYBR Green Supermix, 1 μL of each primer at 10 μM concentrations, 2 μL of DNA template and 6 μL of sterile distilled water. Thermocycling conditions were 95°C for 2 min (denaturation) and then at 95°C for 10 min to activate Taq Polymerase. The amplification was then repeated 40 times (95°C for 15 s and extension at 60°C for 1 min). Negative controls without cDNA were also performed (NTC). A melting curve analysis was made after each run to ensure a single amplified product for every reaction.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analysed with one-way analysis of variance, followed by post hoc Tukey's HSD multiple comparison of means to check the difference in bacterial inhibition between the groups (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

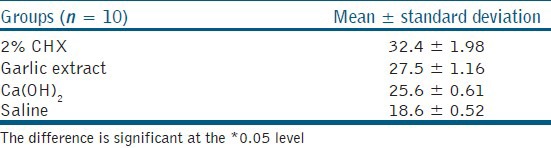

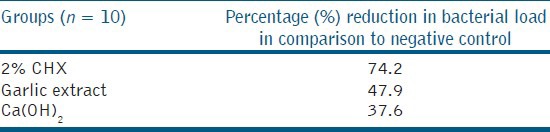

PCR determines the result in threshold cycle (Ct). In our study, 2% CHX (Group one-32.4) showed better antimicrobial efficacy, followed by garlic extract (Group two-27.5), and Ca(OH)2 (Group three-25.6) [Table 1]. Percentage reduction in bacterial load in comparison to saline (negative control) was calculated. CHX (Group one-74.2%) showed the best antibacterial efficacy followed by garlic extract (Group two-47.9%), and Ca(OH)2 (Group three-37.6) [Table 2]. The groups were significant at P < 0.05 level. Garlic extract was found to be statistically significant when compared with Ca(OH)2.

Table 1.

Ct value---Mean and standard deviation for 2% CHX, garlic extract, and Ca(OH)2 against E. faecalis

Table 2.

Percentage change in bacterial load

DISCUSSION

Secondary interradicular infections can result in persistent exudates, interappointment exacerbations, and periradicular lesions despite treatment. Studies have shown that unlike primary endodontic infections which have many causative organisms, secondary or persistent infections associated with endodontic treatment failure are restricted to one or two species. E. faecalis is a gram-positive facultative anerobic bacteria which is predominantly responsible for endodontic treatment failure. Siqueira and Rôças[25] conducted a study in which they reported E. faecalis organism detected in 20 of the 30 cases of persistent endodontic infections associated with root filled teeth. E. faecalis was found to be strongly associated with persistent infections. Odds of detecting E. faecalis in cases of persistent infection associated with treatment failure were found to be nine. Molecular studies have also confirmed that E. faecalis is the most common species found in root-filled teeth associated with persistent infections. Hence, E. faecalis was chosen for our study.

The assessment of efficacy of endodontic medicaments in the disinfection of dentinal tubules was done by using the in vitro model developed by Haapasalo and Ørstavik.[26] Lynne et al.,[27] model was modified to include quantitative analysis of bacteria in dentinal tubules to define a percentage of reduction in bacterial load in infected dentine before and after the application of intracanal medicaments.[15] The model has clear limitations because it does not reflect the situation in apical dentine, which is mostly sclerotic.[28]

PCR-based detection methods enable rapid identification of both cultivable and uncultivable microbial species with high sensitivity and specificity. PCR technology uses a DNA polymerase enzyme to make a huge number of copies of virtually any given piece of DNA or gene. PCR assays are very sensitive and enable rapid identification of microbial species and strains that are difficult or even impossible to culture. Also, in cases with small number of bacteria, negative culture may result, even though viable bacteria may be present because of low sensitivity of culturing technique. The viable but culturable state of E. faecalis under adverse environmental conditions, where the enterococcal cells lose their culturability but are viable, often result in PCR positive/culture negative cases. Thus, a more sophisticated and sensitive molecular technique like PCR was used to assess the effect of antimicrobial agents against E. faecalis.[29]

In our study, 2% CHX showed better antibacterial efficacy compared to garlic extract and Ca(OH)2. The possible reasons might be due to bactericidal dosage of 2% CHX and increased diffusion of the medicament into the dentinal tubules.[15] CHX is a positively charged hydrophobic and lipophilic molecule that interacts with phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides on the cell membrane of bacteria and enters the cell through some type of active or passive transport mechanism. Its efficacy is because of the interaction of the positive charge of the molecule with the negatively charged phosphate groups on microbial cell walls, which alters the cells osmotic equilibrium. This increases the permeability of the cell wall, allowing the CHX molecule to penetrate into the bacteria. Damage to this delicate membrane is followed by leakage of intracellular constituents, particularly phosphate entities such as adenosine triphosphate and nucleic acids. As a consequence, the cytoplasm becomes congealed, with resultant reduction in leakage; thus, there is a biphasic effect on membrane permeability.[15] The result of this present study was similar to that of Krithikadatta et al.,[30] Gomes et al.,[31] and Siqueria and Uzeda,[32] and Bhardwaj et al.[33]

In our study, garlic extract showed better antibacterial efficacy compared to Ca(OH)2. Garlic contains at least 33 sulphur compounds, several enzymes, 17 amino acids, and minerals such as selenium.[34] It contains a higher concentration of sulphur compounds than any other Allium species. The sulphur compounds are responsible both for garlic's pungent odour and many of its medicinal effects. Dried, powdered garlic contains approximately 1% allilin (S-allyl cysteine sulfoxide).[35] One of the most biologically active compounds, allicin (diallyl thiosulfinate or diallyl disulfide) does not exist in garlic until it is crushed or cut; injury to the garlic bulb activates the enzyme allinase, which metabolizes allilin to allicin.[36] Allicin is further metabolized to vinyldithiines. This breakdown occurs within hours at room temperature and within minutes during cooking.[37] Allicin exerted antibacterial activity against Salmonella typhimurium, primarily by interfering with RNA synthesis.[38] This could be the possible reason for the antibacterial efficacy of garlic extract.

CONCLUSION

2% CHX showed better antibacterial efficacy against E. faecalis by using real- time PCR.

Garlic extract showed better antibacterial efficacy compared to Ca(OH)2 against E. faecalis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank - Chancellor's Summer Research Fellowship Grant (2011), Ms. C. D. Mohanapriya, Application Specialist, Central Research Facility, Sri Ramachandra University and Dr. Ganesh, Assistant Professor, Department of Human Genetics and Biomedical Sciences for their support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Chancellor's Summer Research Fellowship Grant (2011)

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Möller AJ, Fabricius L, Dahlén G, Ohman AE, Heyden G. Influence on periapical tissues of indigenous oral bacteria and necrotic pulp tissue in monkeys. Scand J Dent Res. 1981;89:475–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1981.tb01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sedgley CM, Molander A, Flannagan SE, Nagel AC, Appelbe OK, Clewell DB, et al. Virulence, phenotype, genotype characteristics of endodontic Enterococcus spp. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2005;20:10–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2004.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siqueira JF, Jr, Rôcas IN. Polymerase chain reaction-based analysis of microorganisms associated with failed endodontic treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portenier I, Haapasalo H, Orstavik D, Yamauchi M, Haapasalo M. Inactivation of the antibacterial activity of iodine potassium iodide and chlorhexidine digluconate against Enterococcus faecalis by dentin, dentin matrix, type-I collagen, and heat-killed microbial whole cells. J Endod. 2002;28:634–7. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Distel JW, Hatton JF, Gillespie MJ. Biofilm formation in medicated root canals. J Endod. 2002;28:689–93. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishen A, George S, Kumar R. Enterococcus faecalis-mediated biomineralized biofilm formation on root canal dentine in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77:406–15. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safavi KE, Spangberg LS, Langeland K. Root canal dentinal tubule disinfection. J Endod. 1990;16:207–10. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)81670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess W. New York: William Wood & Co; 1925. Anatomy of root canals in the teeth of the permanent dentition. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spångberg LS, Haapasalo M. Rationale and efficacy of root canal medicaments and root filling materials with emphasis on treatment outcome. Endod Top. 2002;2:35–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foreman PC, Barnes IE. Review of calcium hydroxide. Int Endod J. 1990;23:283–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1990.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spangberg LSW. Intracanal medication. In: Ingle JI, Bakland LK, editors. Endodontics. 4th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. pp. 627–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borges FM, de Melo MA, Lima JP, Zanin IC, Rodrigues LK. Antimicrobial effect of chlorhexidine digluconate in dentin: In vitro and in situ study. J Conserv Dent. 2012;15:22–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.92601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaghela DJ, Kandaswamy D, Venkateshbabu N, Jamini N, Ganesh A. Disinfection of dentinal tubules with two different formulations of calcium hydroxide as compared to 2% chlorhexidine: As intracanal medicaments against Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2011;14:182–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.82625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delany GM, Patterson SS, Miller CH, Newton CW. The effect of chlorhexidine gluconate irrigation on the root canal flora of freshly extracted necrotic teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;53:518–23. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90469-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandaswamy D, Venkateshbabu N, Gogulnath D, Kindo AJ. Dentinal tubule disinfection with 2% chlorhexidine gel, propolis, morinda citrifolia juice, 2% povidone iodine, and calcium hydroxide. Int Endod J. 2010;43:419–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldberg RS, Chang SC, Kotik AN, Nadler M, Neuwirth Z, Sundstrom DC, et al. In vitro mechanism of inhibition of bacterial cell growth by allicin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1763–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.12.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ariga T, Oshiba S, Tamada T. Platelet aggregation inhibitor in garlic. Lancet. 1981;1:150–1. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90729-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milner JA. Garlic: Its anticarcinogenic and antitumorigenic properties. Nutr Rev. 1996;54:S82–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1996.tb03823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reuter HD, Koch HP, Lawson LD. Garlic: The science and therepeutic applications of allium sativum L. and Related Species. In: Koch HP, Lawson LD, editors. 2nd ed. Maryland: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. pp. 135–212. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chavan SD, Shetty NL, Kanuri M. Comparative evaluation of garlic extract mouthwash and chlorhexidine mouthwash on salivary Streptococcus mutans count - An in vitro study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8:369–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujisawa H, Watanabe K, Suma K, Origuchi K, Matsufuji H, Seki T, et al. Antibacterial potential of garlic-derived allicin and its cancellation by sulfhydryl compounds. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:1948–55. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen YY, Chiu HC, Wang YB. Effects of Garlic Extract on acid production and growth of streptococcus mutans. J Food Drug Anal. 2009;17:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nawal RR, Parande M, Sehgal R, Naik A, Rao NR. A comparative evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy and flow properties of Epiphany, Guttaflow and AH-Plus sealer. Int Endod J. 2011;44:307–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fouad AF, Barry J, Caimano M, Clawson M, Zhu Q, Carver R, et al. PCR-based identification of bacteria associated with endodontic infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3223–31. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3223-3231.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siqueira JF, Jr, Rôças IN. Exploiting molecular methods to explore endodontic infections: Part 2-Redefining the endodontic microbiota. J Endod. 2005;31:488–98. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000157990.86638.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haapasalo M, Orstavik D. In vitro infection and disinfection of dentinal tubules. J Dent Res. 1987;66:1375–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660081801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynne RE, Liewehr FR, West LA, Patton WR, Buxton TB, McPherson JC. In vitro antimicrobial activity of various medication preparations on E. Faecalis in root canal dentin. J Endod. 2003;29:187–90. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paqué F, Luder HU, Sener B, Zehnder M. Tubular sclerosis rather than the smear layer impedes dye penetration into the dentine of endodontically instrumented root canals. Int Endod J. 2006;39:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams JM, Trope M, Caplan DJ, Shugars DC. Detection and quantitation of E. Faecalis by real-time PCR (qPCR), reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), and cultivation during endodontic treatment. J Endod. 2006;32:715–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krithikadatta J, Indira R, Dorothykalyani AL. Disinfection of dentinal tubules with 2% chlorhexidine, 2% metronidazole, bioactive glass when compared with calcium hydroxide as intracanal medicaments. J Endod. 2007;33:1473–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomes BP, Souza SF, Ferraz CC, Teixeira FB, Zaia AA, Valdrighi L, et al. Effectiveness of 2% chlorhexidine gel and calcium hydroxide against Enterococcus faecalis in bovine root dentin in vitro. Int Endod J. 2003;36:267–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siqueira JF, Jr, Uzeda M. Intracanal medicaments: Evaluation of the antibacterial effects of chlorhexidine, metronidazole, and calcium hydroxide associated with three vehicles. J Endod. 1997;23:167–9. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhardwaj A, Ballal S, Velmurugan N. Comparative evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of natural extracts of Morinda citrifolia, papain and aloe vera (all in gel formulation), 2% chlorhexidine gel and calcium hydroxide, against Enterococcus faecalis: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2012;15:293–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.97964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newall CA, Anderson LA, Phillipson JD. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 1996. Herbal medicines: A guide for health-care professionals; p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monographs on the medicinal uses of plants. Exeter: European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy; 1997. World Health Organisation. Fasicules 3-5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Block E. The chemistry of garlic and onions. Sci Am. 1985;252:114–9. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0385-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blania G, Spangenberg B. Formation of allicin from dried garlic (Allium sativum): A simple HPTLC method for simultaneous determination of allicin and ajoene in dried garlic and garlic preparations. Planta Med. 1991;57:371–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feldberg RS, Chang SC, Kotik AN, Nadler M, Neuwirth Z, Sundstrom DC, et al. In vitro mechanism of inhibition of bacterial cell growth by allicin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1763–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.12.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]