Abstract

Periapical inflammatory lesion is the local response of bone around the apex of tooth that develops after the necrosis of the pulp tissue or extensive periodontal disease. The final outcome of the nature of wound healing after endodontic surgery can be repair or regeneration depending on the nature of the wound; the availability of progenitor cells; signaling molecules; and micro-environmental cues such as adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix, and associated non-collagenous protein molecules. The purpose of this case report is to add knowledge to the existing literature about the combined use of graft material [platelet rich fibrin (PRF) and hydroxyapatite (HA)] and barrier membrane in the treatment of large periapical lesion.

A periapical endodontic surgery was performed on a 45 year old male patient with a swelling in the upper front teeth region and a large bony defect radiologically. The surgical defect was filled with a combination of PRF and HA bone graft crystals. The defect was covered by PRF membrane and sutured.

Clinical examination revealed uneventful wound healing. Radiologically the HA crystals have been completely replaced by new bone at the end of 2 years.

On the basis of the results obtained in our case report, we hypothesize that the use of PRF in conjunction with HA crystals might have accelerated the resorption of the graft crystals and would have induced the rapid rate of bone formation.

Keywords: Hydroxyapatite, periapical inflammatory lesion, platelet rich fibrin, platelet rich fibrin membrane, regeneration

INTRODUCTION

Regeneration is defined as the reproduction or reconstitution of a lost or injured part of the body in such a way that the architecture and function of the lost or injured tissues are completely restored.[1] The final outcome of the nature of wound healing after endodontic surgery can be repair or regeneration depending on the nature of the wound; the availability of progenitor cells; signaling molecules; and micro-environmental cues such as adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix, and associated non-collagenous protein molecules.[2] Since repair is not an ideal outcome after wound healing, regenerative approaches that aim to restore the lost tissues (periodontal ligament, bone, cementum, and connective tissue) have been introduced.[3] Regenerative therapies like bone graft and barrier membranes have been used for the optimal healing of the periapical defect area after degranulation of the lesion.[4]

Porous hydroxyapatite (HA) has been used to fill the periodontal intrabony defects, which has resulted in clinically acceptable responses.[5] It has been shown that porous HA bone grafts have excellent bone conductive properties, which permit outgrowth of osteogenic cells from existing bone surfaces into the adjacent bone material.[6] Since there are no organic components contained in HA, this bone graft material does not induce any allergic reaction and is clinically very well tolerated.[7] However, true regeneration is not achieved with HA because, healing which occurs is just a connective tissue encapsulation of the graft.[8]

Barrier membranes are inert materials that maintains a confined space, which is one of the key biologic requirements for bone regeneration.[9] When a space is formed after periapical surgery, cells from the adjacent tissues will grow into this space to form their parent tissue. Membranes are placed to give preference to cells from desired tissues and to prevent cells from undesired tissues that have access to the space.[2]

Platelet rich fibrin (PRF) is an immune and platelet concentrate with specific composition, three dimensional architecture and associated biology that collects all the constituents of a blood sample to favor wound healing and immunity.[10,11] PRF contains multitude of growth factors like platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor β1 (TGF β1), insulin like growth factor (IGF), etc., exhibiting varied potent local properties such as cell migration, cell attachment, cell proliferation, and cell differentiation.[12] It has been shown as an ideal biomaterial for pulp-dentin complex regeneration.[13]

PRF is both a healing and interpositional biomaterial. As a healing material, it accelerates wound closure and mucosal healing due to fibrin bandage and growth factor release. As interpositional material, it avoids the early invagination of undesired cells, thereby behaves as a competetive barrier between desired and undesired cells.[11]

Sculean et al.[14] in their study concluded that the combination of barrier membrane and grafting materials may result in histological evidence of periodontal regeneration, predominantly bone repair. Gassling et al. proved in their study that PRF membranes are suitable for cultivation of periosteal cells for bone tissue engineering.[15] Pradeep et al. in their study concluded that when HA is combined with PRF, it increases the regenerative effects observed with PRF in the treatment of human three wall intrabony defects.[16] The purpose of this case report is to add knowledge to the existing literature about the combined use of graft material and barrier membrane in the treatment of large periapical lesion. Literature survey reveals that there is no documentation of case report using combination of PRF, HA, and PRF membrane in the management of large inflammatory periapical lesion.

CASE REPORT

A 45-years-old male patient came to the Department of Endodontics with a chief complaint of swelling in the upper front teeth region (teeth #7 and #8). The patient had no medical contraindication to dental treatment. Dental history revealed an incident of trauma to the upper front teeth region 5 years ago. Clinical examination revealed discolored tooth #8 with an Ellis class 2 fracture. Both the teeth #7 and #8 were sensitive to percussion test. Upon radiographic examination gigantic periapical radiolucencies were observed at the apical region of teeth #7 and #8 [Figures 1a and 2a].

Figure 1.

(a) Pre-operative clinical picture (b) 15 mm × 16 mm × 16 mm gigantic lesion exposed along with root end resection being done (c) Combination of platelet rich fibrin (PRF) clot and hydroxyapatite crystals placed over the defect (d) 2 layers of PRF membrane placed covering the edge of the defect (e) post-operative clinical picture

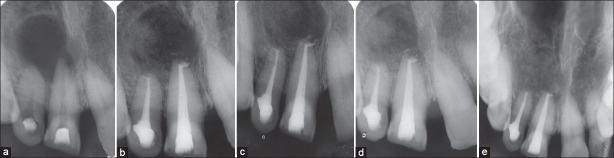

Figure 2.

(a) Pre-operative intra oral radiograph (b) 3 months follow up (c) 6 months follow up (d) 1 year follow-up (e) 2 year follow-up. Hydroxyapatite crystals totally resorbed and replaced by new bone

The root canal treatment was performed using step back technique till an apical size of # 55 and #45 in relation to teeth #8 and #7 respectively. 5.25% sodium hypochlorite solution (Novo Dental Product Pvt Ltd, Mumbai, India) was used to irrigate the canals during the canal preparation. The root canal treatment was performed in three visits and calcium hydroxide was used as the intracanal medicament. The root canals were obturated using gutta percha (Dentsply maillefer Ballaigues) and AH 26 (Dentsply DeTrey GmbH, Philadelphia, USA) by the lateral condensation technique. After a review period of 6 months, expected healing did not occur. Hence, a periapical endodontic surgery was planned. Under local anesthesia (1:200000 adrenaline, DJ Lab, India), a full thickness mucoperiosteal flap was reflected by a sulcular incision starting from the distal of the tooth #9 to distal of the tooth #6. A large periapical defect was seen with complete loss of labial cortical plate. The lesion measured 15 mm × 16 mm × 16 mm corresponding to the length, width, and depth of the lesion [Figure 1b]. Tissue curettage was done at the defect site followed by thorough irrigation using sterile saline solution. Using #702 tapered fissure bur (SS White burs), root end resection was performed in teeth #7 and #8 and Grey mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) (ProRoot MTA; Dentsply, Tulsa, OK, USA) was used as the root end filling material. 20 mL of blood was drawn from the patient's antecubital vein and centrifuged (REMI centrifuge machine Model R-8c with 12 × 15 mL swing out head) for 10 min under 3000 revolutions (approximately 400 g) per minute to obtain the PRF. Commercially available HA bone graft crystals (Biograft HA, IFGL Bioceramics Ltd., India) were sprinkled over the PRF gel and together the mixture was placed into defect site [Figure 1c]. PRF membrane was prepared with compresses and placed as two layers covering the edge of the defect [Figure 1d]. Flap stabilization was done followed by suturing using 3-0 black silk suture material (Sutures India Pvt. Ltd, Karnataka, India). Patient was kept under the antibiotic (amoxycillin) coverage along with Affen PLUS Tab (Dr. Reddy's Lab, Andrapradesh, India) and 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate solution as mouth rinse for a period of 5 days. Suture removal was done 1 week later and the healing was uneventful [Figure 1e].

Patient was reviewed at 3 months [Figure 2b], 6 months [Figure 2c], 1 year [Figure 2d], and 2-year period during which there were no symptoms of pain, inflammation, or discomfort. These follow-up visits included routine intraoral examinations and professional plaque control. Radiographically, HA particles have been almost completely resorbed and replaced with new bone at the end of 2 years [Figure 2e]. Patient was completely satisfied with the results of the treatment.

DISCUSSION

The four critical factors that influence bone regeneration after the periapical surgery are primary wound closure, angiogenesis as a blood supply and source of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, space maintenance, and stability of the wound (PASS principle).[17] HA has shown positive results with respect to periodontal regeneration in periapical defects.[3] It has been reported that combination of HA with PRF resulted in greater pocket depth reduction, gain in clinical attachment and defect fill than PRF used alone.[16] For this reason, we chose HA, as that it could enhance the effects of PRF by maintaining the space for tissue regeneration to occur, as well as by exerting an osteoconductive effect in the bony defect area. Bone grafts alone without a blood clot or angiogenic factors are unlikely to be capable of promoting periapical wound healing.[18] Biologically, a blood clot is a better space filler than all bone grafting materials. A blood clot is the host's own biologic product and is indispensable in tissue wound healing. Tissue wound healing would be impaired without a blood clot,[19,20] as in a dry socket after tooth extraction.[2]

PRF is in the form of a platelet gel and can be used in conjunction with bone grafts, which offers several advantages including promoting wound healing, bone growth and maturation, graft stabilization, wound sealing, and hemostasis and improving the handling properties of graft materials.[19] PRF is a concentrated suspension of the growth factors found in platelets. These growth factors are involved in wound healing and are postulated as promoters of tissue regeneration. Clinical trials suggest that the combination of bone graft along with the growth factors in the PRF may be suitable to enhance the bone density.[19] PRF is a rich source of PDGF, TGF, and IGF, etc., In vivo application of PDGF increased bone regeneration in calvarial defects when a bio-absorbable membrane was used as a carrier.[20] TGF-stimulates bio-synthesis of type I collagen and induces deposition of bone matrix in vitro.[21] When TGF-was applied with a biodegradable osteogenic material, bone growth around calvarial defects increased significantly.[22] IGF-I stimulates bone formation by proliferation and differentiation,[23] and it is synthesized and secreted by osteoblasts.[24] An increase in the proliferation of human osteoblasts has been demonstrated with a combination of PDGF, IGF-I, TGF, and epidermal growth factor.[25]

The intended role of the PRF membrane in our case report was to contain the HA and PRF in the bony defect in the early phase of wound healing. PRF can serve as a resorbable membrane, which can be used in pre-prosthetic surgery and implantology to cover bone augmentation site.[10] Since the surface of PRF membrane is smoother, it can cause superior proliferation of human periosteal cells thereby enhancing bone regeneration.[15] The progressive polymerization mode of coagulation in PRF helps in the increased incorporation of the circulating cytokines into the fibrin meshes (intrinsic cytokines) which helps in wound healing by moderating the inflammation.[15,26] In our case report, two layers of PRF membranes were placed over the defect because, firstly this membrane is a thin fibrin scaffold that might undergo quick resorption, secondly PRF membranes are inhomogenous, since leukocytes and platelet aggregates are concentrated within one end of the membrane. Therefore, the use of two membrane layers with membranes in opposite sense, allows to have the same components (platelets, leukocytes, fibronectin, vitronectin) on the whole surgical surface.[11] The membrane was slightly hanged over the edge of the wound as it controls the migration of the different tissue families on the wounded site thereby directing the organization of the wound.

To conclude, PRF membrane has been used as a barrier membrane over a large bony defect to maintain a confined space for the purpose of guided tissue regeneration. On the basis of the results obtained in our case report, we hypothesize that the use of PRF in conjunction with HA crystals might have accelerated the resorption of the graft crystals and would have induced the rapid rate of bone formation. However, histological studies are required to examine the nature of newly formed tissue in the defect and long-term, controlled clinical trial will be required to know the effect of this combination over bone regeneration.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Bosshardt DD, Sculean A. Does periodontal tissue regeneration really work? Periodontol 2000. 2009;51:208–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin L, Chen MY, Ricucci D, Rosenberg PA. Guided tissue regeneration in periapical surgery. J Endod. 2010;36:618–25. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashutski JD, Wang HL. Periodontal and endodontic regeneration. J Endod. 2009;35:321–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demiralp B, Keçeli HG, Muhtaroğullar M, Serper A, Demiralp B, Eratalay K. Treatment of periapical inflammatory lesion with the combination of platelet-rich plasma and tricalcium phosphate: A case report. J Endod. 2004;30:796–800. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000136211.98434.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenney EB, Lekovic V, Han T, Carranza FA, Jr, Dimitrijevic B. The use of a porous hydroxylapatite implant in periodontal defects. I Clinical results after six months. J Periodontol. 1985;56:82–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.2.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen JA, Mellonig JT, Gray JL, Towle HT. Comparison of decalcified freeze-dried bone allograft and porous particulate hydroxyapatite in human periodontal osseous defects. J Periodontol. 1989;60:647–54. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.12.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meffert RM, Thomas JR, Hamilton KM, Brownstein CN. Hydroxylapatite as an alloplastic graft in the treatment of human periodontal osseous defects. J Periodontol. 1985;56:63–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.2.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stahl SS, Froum SJ. Histologic and clinical responses to porous hydroxylapatite implants in human periodontal defects. Three to twelve months postimplantation. J Periodontol. 1987;58:689–95. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.10.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman T, Klokkevold, Carranza . 10th ed. Saunders, Elsevier publication: Localized bone augmentation and implant site development; 2006. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology; p. 1134. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choukroun J, Diss A, Simonpieri A, Girard MO, Schoeffler C, Dohan SL, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part IV: Clinical effects on tissue healing. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Corso M, Sammartino G, Dohan Ehrenfest DM. Re: Clinical evaluation of a modified coronally advanced flap alone or in combination with a platelet-rich fibrin membrane for the treatment of adjacent multiple gingival recessions: A 6-month study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1694–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaigler D, Cirelli JA, Giannobile WV. Growth factor delivery for oral and periodontal tissue engineering. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2006;3:647–62. doi: 10.1517/17425247.3.5.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shivashankar VY, Johns DA, Vidyanath S, Kumar MR. Platelet rich fibrin in the revitalization of tooth with necrotic pulp and open apex. J Conserv Dent. 2012;15:395–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.101926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sculean A, Nikolidakis D, Schwarz F. Regeneration of periodontal tissues: Combinations of barrier membranes and grafting materials-biological foundation and preclinical evidence: A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:106–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gassling V, Douglas T, Warnke PH, Açil Y, Wiltfang J, Becker ST. Platelet-rich fibrin membranes as scaffolds for periosteal tissue engineering. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:543–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pradeep AR, Bajaj P, Rao NS, Agarwal E, Naik SB. Platelet-rich fibrin combined with a porous hydroxyapatite graft for the treatment of three-wall intrabony defects in chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1499–507. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyapati L, Wang HL. The role of stress in periodontal disease and wound healing. Periodontol 2000. 2007;44:195–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laurell L, Gottlow J. Guided tissue regeneration update. Int Dent J. 1998;48:386–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1998.tb00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sunitha Raja V, Munirathnam Naidu E. Platelet-rich fibrin: Evolution of a second-generation platelet concentrate. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:42–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.38931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung CP, Kim DK, Park YJ, Nam KH, Lee SJ. Biological effects of drug-loaded biodegradable membranes for guided bone regeneration. J Periodontal Res. 1997;32:172–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeilschifter J, Oechsner M, Naumann A, Gronwald RG, Minne HW, Ziegler R. Stimulation of bone matrix apposition in vitro by local growth factors: A comparison between insulin-like growth factor I, platelet-derived growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta. Endocrinology. 1990;127:69–75. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-1-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnaud E, Morieux C, Wybier M, de Vernejoul MC. Potentiation of transforming growth factor (TGF-beta 1) by natural coral and fibrin in a rabbit cranioplasty model. Calcif Tissue Int. 1994;54:493–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00334331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hock JM, Centrella M, Canalis E. Insulin-like growth factor I has independent effects on bone matrix formation and cell replication. Endocrinology. 1988;122:254–60. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-1-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker NL, Carlo Russo V, Bernard O, D’Ercole AJ, Werther GA. Interactions between bcl-2 and the IGF system control apoptosis in the developing mouse brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;118:109–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piché JE, Graves DT. Study of the growth factor requirements of human bone-derived cells: A comparison with human fibroblasts. Bone. 1989;10:131–8. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(89)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part III: Leucocyte activation: A new feature for platelet concentrates? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e51–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]