Abstract

Drugs that kill tuberculosis more quickly could shorten chemotherapy significantly. In Escherichia coli, a common mechanism of cell death by bactericidal antibiotics involves the generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton reaction. Here we show that vitamin C, a compound known to drive the Fenton reaction, sterilizes cultures of drug-susceptible and drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis. While M. tuberculosis is highly susceptible to killing by vitamin C, other Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens are not. The bactericidal activity of vitamin C against M. tuberculosis is dependent on high ferrous ion levels and reactive oxygen species production and causes a pleiotropic effect affecting several biological processes. This study enlightens the possible benefits of adding vitamin C to an anti-tuberculosis regimen and suggests that the development of drugs that generate high oxidative burst could be of great use in tuberculosis treatment.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), a disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis, shares with HIV and malaria, the distinction of being one of the deadliest infectious diseases of our time. The World Health Organization estimates that one third of the world’s population is infected with M. tuberculosis. Chemotherapy, the cornerstone of TB control efforts, is compromised by the emergence of M. tuberculosis strains resistant to several, if not all, drugs available to treat the disease. The development of drug-resistant infections in TB patients is often associated with failure to complete the lengthy chemotherapy. Drug-susceptible TB is treated with isoniazid (INH), rifampicin (RIF), pyrazinamide and ethambutol for two months followed by four months of INH and RIF, while treatment of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) TB can require up to two years of chemotherapy with possible damaging side effects. Drugs that kill M. tuberculosis more quickly while also preventing the development of drug resistance could shorten chemotherapy significantly.

In the TB pharmacopeia, the first-line drugs INH and RIF are bactericidal, killing 99 to 99.9% of M. tuberculosis cells in vitro within four to seven days. Unfortunately, resistance emerges very rapidly, both in vitro and in vivo1–3. In Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, a common mechanism of killing by bactericidal drugs, regardless of their target, involves the generation of hydroxyl radicals by the Fenton reaction4 (although this mechanism was recently disputed5,6) or by protein mistranslation and stress-response two-component system activation7. Hydroxyl radicals induce cell death via DNA damage, which is due in part to the oxidation of the guanine nucleotide pool8. Hydroxyl radicals can be produced by the combination of the Haber-Weiss cycle9 and the Fenton reaction10. In these reactions, ferrous ion reacts with oxygen to produce superoxide (1), which by dismutation leads to hydrogen peroxide formation (2). Hydrogen peroxide then reacts with ferrous ions to form hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton reaction (3).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

In the presence of reductants, ferrous ions are produced by reduction of ferric ions. One reductant known to drive the Fenton reaction is vitamin C (ascorbic acid)11.

Vitamin C is an essential nutrient for some mammals and has potent antioxidant properties. The addition of vitamin C to the human diet has led to the elimination of scurvy12 and some improvement in the treatment of viral and bacterial infections, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, gout, and cataracts13–15. Conflicting reports have suggested either beneficial or no effect of vitamin C in the treatment of TB16. In the 1930’s, McConkey and Smith showed that, in guinea pigs fed with tuberculous sputum and tomato juice simultaneously, only 6% developed intestinal TB, while 70% of the control group, which did not receive any vitamin C supplement, developed ulcerative intestinal TB17. A few years later, Pichat and Reveilleau demonstrated that vitamin C could sterilize M. tuberculosis cultures in vitro and postulated that the bactericidal activity could be due to both vitamin C and its decomposition product(s)18,19. More recently, vitamin C treatment of M. tuberculosis was found to be bacteriostatic and to induce a dormant drug-tolerant phenotype20 while another study found a correlation between the high vitamin C content of some medicinal plant extracts and their activity against M. tuberculosis21.

In this report, we describe the activity of vitamin C against drug-susceptible, MDR- and extensively drug-resistant (XDR)-M. tuberculosis. We show that the sterilizing effect of vitamin C on M. tuberculosis in vitro was due to the presence of high iron concentration, ROS production and DNA damage. The dramatic killing of drug-susceptible, MDR and XDR M. tuberculosis strains by vitamin C in vitro argues for further studies on the benefits of a high vitamin C diet in TB-treated patients and on the development of bactericidal drugs based on ROS production.

Results

High doses of vitamin C sterilize M. tuberculosis cultures in vitro

Previous studies on the effect of vitamin C on M. tuberculosis emphasized the fact that high concentrations of vitamin C were necessary to observe any effect18. Therefore, we first determined that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of vitamin C that prevented the growth of M. tuberculosis was 1 mM (Table 1). Killing kinetic curves were then obtained by treating M. tuberculosis H37Rv with different concentrations of vitamin C (from 1/10 MIC to 4× MIC) and plating for colony-forming units (CFUs) over the course of four weeks. A dose-response relationship was observed and a bactericidal activity was obtained at 2 mM (Fig. 1a). Strikingly, 4 mM vitamin C sterilized a M. tuberculosis culture in three weeks. At the MIC (1 mM), vitamin C had a brief bacteriostatic effect followed by resumption of growth. Since vitamin C is rapidly oxidized into dehydroascorbic acid by air, we examined if the limited activity at 1 mM was due to vitamin C degradation. M. uberculosis was treated with daily addition of 1 mM vitamin C for the first 4 days. As a result, M. tuberculosis was killed as rapidly with daily addition of 1 mM vitamin C as with one dose of 4 mM at day 0 (Fig. 1a). The killing by vitamin C was not due to acidification of the media since the addition of 4 mM vitamin C to an M. tuberculosis culture did not alter the pH significantly. The activity of vitamin C against M. tuberculosis led us to test whether vitamin C was also active against other Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Table 1). Interestingly, vitamin C activity against M. tuberculosis was rather specific since the MICs for non-mycobacteria were at least 16 to 32 times higher than against M. tuberculosis. M. tuberculosis was also the most susceptible strain to vitamin C among the mycobacterial strains tested (Table 1).

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of vitamin C against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial species.

| Strain | MIC (mM) |

|---|---|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | 1 |

| H37Rv ΔmshA | 0.015 |

| H37Rv ΔmshA pMV361::mshA | 1 |

| Mycobacterium avium | 8 |

| Mycobacterium marinum | 8 |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 | 8 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 16 |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | >32 |

| Escherichia coli | 32 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 16 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | >32 |

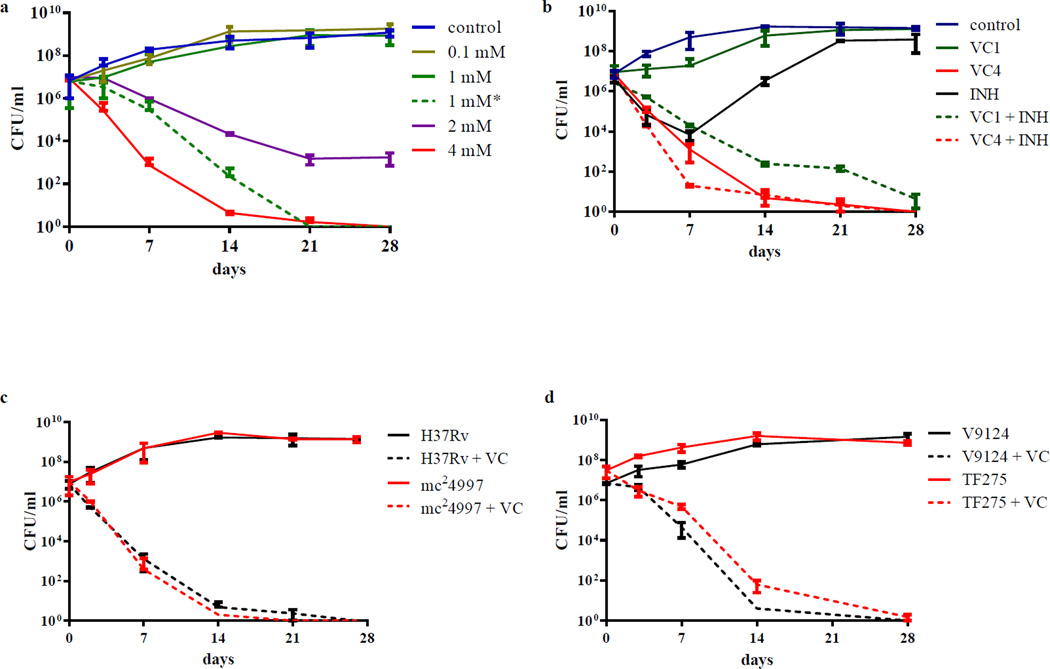

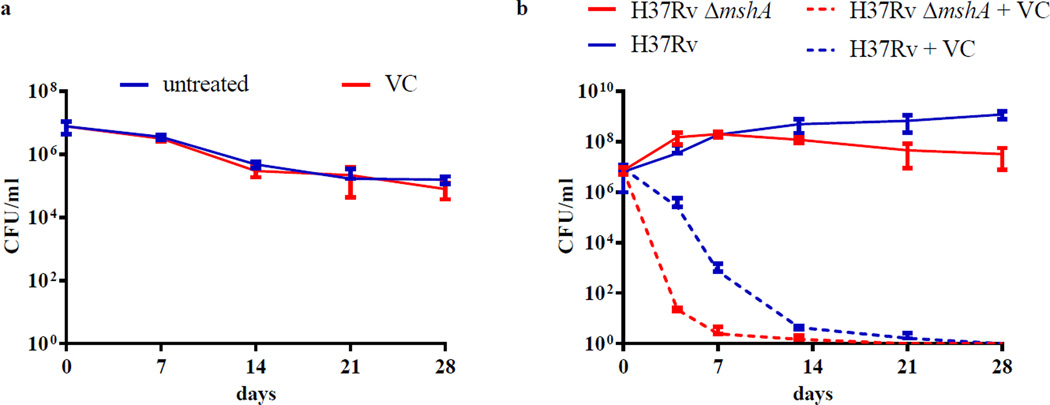

Figure 1. Vitamin C sterilizes drug-susceptible and drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains.

(a) M. tuberculosis H37Rv cultures grown to an OD600nm of ≈ 0.75 were diluted 1/20 and treated with increasing amounts of vitamin C (VC, from 0.1 mM to 4 mM). 1 mM* represents an experiment where 1 mM of vitamin C was added to the culture daily for the first 4 days of treatment. (b) M. tuberculosis H37Rv was treated with INH (7 µM, 20× MIC), vitamin C (1 or 4 mM) and a combination of INH and vitamin C (1 and 4 mM). (c) mc24997, a RIF- and INH-resistant M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain was treated with vitamin C (4 mM). (d) Vitamin C (4 mM) was added to a drug-susceptible strain (V9124) and to an extensively drug-resistant strain (TF275) of M. tuberculosis from the Kwa-Zulu Natal province of South Africa. Growth was followed and CFUs were determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions and incubating the plates at 37°C for 4 weeks. The experiments were done at least in triplicate and the average with standard deviation is plotted.

To compare the effects of vitamin C to the known mycobactericidal drug INH, we treated M. tuberculosis with vitamin C and/or INH (Fig. 1b). For the first four days of treatment, the kinetics of killing of M. tuberculosis were similar between INH and 4 mM vitamin C. By ten days, INH-treated M. tuberculosis gave rise to INH-resistant mutants while vitamin C treatment was still bactericidal. We also tested INH and 4 mM vitamin C together and the combined action was not antagonistic. Interestingly, 1 mM vitamin C in combination with INH also resulted in sterilization of the culture.

One of the main impediments to TB control and eradication is the high prevalence of drug-resistant strains. To assess the effect of vitamin C on drug-resistant strains, MDR (mc2499722) and XDR (TF27523) M. tuberculosis strains were treated with 4 mM vitamin C for four weeks. The killing of mc24997 by vitamin C was indistinguishable from that observed for H37Rv (Fig. 1c), resulting in more than 100,000-fold decrease in CFUs in two weeks. The activity of vitamin C against TF275 was compared to a putatively ancestral drug-susceptible KwaZulu-Natal strain, V912423 (Fig. 1d). With both strains, a 100,000 fold or more reduction in CFUs was observed after two weeks of vitamin C treatment, although the XDR-TB strain seemed slightly less sensitive to vitamin C.

Vitamin C increases iron concentrations in M. tuberculosis cultures

In order to decipher the mechanisms underlying the killing of M. tuberculosis by vitamin C in vitro, the isolation of vitamin C-resistant mutants of M. tuberculosis was attempted. In three independent experiments, approximately 109 M. tuberculosis cells were plated on Middlebrook 7H10 plates containing 4 mM vitamin C and despite incubating the plates for over 2 months, no spontaneous mutants ever arose. Next, the transcriptional response of M. tuberculosis to vitamin C (4 mM) after two days of treatment was examined. The up-regulated genes in vitamin C-treated samples were involved in lipid biosynthesis and intermediary metabolisms such as amino acid, cofactor, and carbohydrate biosyntheses and degradation (Table 2). Among the most highly upregulated genes were those encoding enzymes containing divalent cations in their active sites and this was hypothesized as the displacement of divalent cations by excess iron. This interpretation was supported by the finding that the most down-regulated gene, mbtD, is involved in biosynthesis of the siderophore mycobactin (Table. 2). When M. tuberculosis is grown in the presence of high concentrations of iron, the levels of mycobactin have been shown to decrease and the mycobactin biosynthesis genes are repressed24. There is a duality to the effects of vitamin C: it acts either as an anti-oxidant or as a pro-oxidant25. As a pro-oxidant, vitamin C can drive the Fenton reaction by reducing ferric ions to ferrous ions11. Most iron within the cell is bound within porphyrins and proteins as ferric ions are very sparingly soluble and ferrous ions are very reactive. To examine the role of iron concentration in vitamin C bactericidal activity, the concentrations of bound iron and reduced and oxidized free iron were measured in M. tuberculosis cultures treated with vitamin C. For safety reasons, the experiments were done with mc26230 (H37Rv ΔRD1 ΔpanCD), an M. tuberculosis strain that can be used in a biosafety level 2 laboratory. In vitamin C-treated samples, intracellular free iron levels were increased by 50 to 75% compared to the untreated cultures after three days while extracellular free iron concentrations were nearly four-fold higher than that of the untreated cultures (Fig. 2a). This increase in free iron levels was also dose-dependent. With 1 mM vitamin C, which had only a bacteriostatic effect for a brief period, the iron concentrations were similar to the untreated samples (Fig. 2a). This large increase in free iron concentrations in the supernatant could also be correlated with a change in supernatant color in M. tuberculosis treated with vitamin C. Similar to what Pichat and Reveilleau described18, we observed that M. tuberculosis cultures treated with vitamin C acquired an orange color after 24 hr. The coloration intensified in the first few days of treatment and then persisted for the duration of treatment. Since the coloration of the supernatant appeared within 24 hr, iron concentrations were determined over the first four days of treatment (Fig 2b). Even at day one, an increase in free iron content in both the cell pellet and the supernatant was observed, which peaked at day three.

Table 2.

Transcriptional profile of vitamin C-treated M. tuberculosis reveals a possible displacement of divalent cations.

| Up-regulated | Down-regulated | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Annotation | Cl | FC | Gene | Annotation | Cl | FC |

| psd | Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase | 1 | 3.11 | mbtD | Polyketide synthetase | 1 | −2.30 |

| dapE | Succinyl-diaminopimelate desuccinylase | 7 | 2.54 | fadA6 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase | 1 | −2.30 |

| hsdM | Type I restriction system DNA methylase | 2 | 2.01 | Rv1096 | Possible glycosyl hydrolase | 7 | −2.10 |

| lytB1 | Probable Lytb-related protein | 3 | 1.98 | fbiC | F420 synthase | 7 | −2.06 |

| Rv1885c | Chorismate mutase | 7 | 1.91 | nei | Probable endonuclease VIII | 7 | −2.04 |

| Rv3833 | Transcriptional regulatory protein | 7 | 1.61 | umaA | Possible mycolic acid synthase | 1 | −1.99 |

| Rv0561c | Possible oxidoreductase | 7 | 1.57 | Rv2859c | Possible amidotransferase | 7 | −1.93 |

| accD2 | Probable acetyl-/propionyl-CoA carboxylase | 1 | 1.55 | pmmB | Probable phosphomannomutase | 7 | −1.83 |

| cysS | Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase | 2 | 1.54 | glgP | Probable glycogen phosphorylase | 7 | −1.62 |

| Rv1167c | Probable transcriptional regulatory protein | 9 | 1.53 | glbN | Probable hemoglobin | 7 | −1.56 |

| lipP | Probable esterase/lipase | 7 | 1.42 | carA | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase small subunit | 7 | −1.53 |

| nadD | Nicotinic acid mononucleotide adenyltransferase | 7 | 1.41 | hab | Probable hydroxylaminobenzene mutase | 7 | −1.45 |

| ureC | Urease alpha subunit (urea amidohydrolase) | 7 | 1.41 | mce4A | Mce-family protein | 0 | −1.39 |

| rpfA | Possible resuscitation-promoting factor | 3 | 1.38 | ahpD | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase | 0 | −1.39 |

| Rv0892 | Probable monooxygenase | 7 | 1.32 | Rv1526c | Probable glycosyltransferase | 7 | −1.34 |

| ksgA | Dimethyladenosine transferase | 2 | 1.29 | rpmG2 | 50s ribosomal protein l33 | 2 | −1.27 |

| Rv2296 | Haloalkane dehalogenase | 7 | 1.26 | Rv3742c | Possible oxidoreductase | 7 | −1.25 |

| phoH1 | Probable PhoH-like protein | 7 | 1.24 | ephF | Possible epoxide hydrolase | 0 | −1.23 |

| argC | N-acetyl-gamma-glutamyl-phosphate reductase | 7 | 1.23 | rsfA | Anti-anti-sigma factor | 2 | −1.23 |

| cysK2 | Possible cysteine synthase A | 7 | 1.15 | lpqU | Probable conserved lipoprotein | 3 | −1.19 |

| ureD | Probable urease accessory protein | 7 | 1.15 | Rv0338c | Probable iron-sulfur-binding reductase | 7 | −1.19 |

| cobM | Probable precorrin-4 C11-methyltransferase | 7 | 1.14 | Rv3777 | Probable oxidoreductase | 7 | −1.11 |

| fadE16 | Possible acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 1 | 1.13 | ideR | Iron-dependent repressor and activator | 9 | −1.10 |

| mce3C | Mce-family protein | 0 | 1.13 | prrA | Two-component response transcriptional regulatory | 9 | −1.10 |

| bioB | Biotin synthase | 7 | 1.07 | cysS | Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase | 7 | −1.09 |

| dipZ | cytochrome biogenesis protein | 7 | 1.07 | moaE1 | Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein | 7 | −1.09 |

| arsC | Arsenic-transport integral membrane protein | 3 | 1.07 | Rv2957 | Possible glycosyl transferase | 7 | −1.06 |

| Rv1516c | Probable sugar transferase | 7 | 1.06 | Rv0338c | Probable iron-sulfur-binding reductase | 7 | −1.19 |

| fixA | Probable electron transfer flavoprotein | 7 | 1.06 | Rv3777 | Probable oxidoreductase | 7 | −1.11 |

| cyp141 | Probable cytochrome p450 141 | 7 | 1.04 | ideR | Iron-dependent repressor and activator | 9 | −1.10 |

| grcC1 | Probable polyprenyl-diphosphate synthase | 1 | 1.03 | prrA | Two-component response transcriptional regulatory | 9 | −1.10 |

| folD | methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase | 7 | 1.03 | cysS | Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase | 7 | −1.09 |

| Rv1158c | Conserved hypothetical ALA-, PRO-rich protein | 7 | 1.01 | moaE1 | Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein | 7 | −1.09 |

| hemZ | Ferrochelatase | 7 | 0.98 | Rv2957 | Possible glycosyl transferase | 7 | −1.06 |

| cyp128 | Probable cytochrome P450 128 | 7 | 0.98 | ||||

| MT2963 | Siderophore utilization protein | 7 | 0.98 | ||||

| Rv1344 | Acyl carrier protein | 1 | 0.98 | ||||

| impA | Probable inositol-monophosphatase | 7 | 0.97 | ||||

| echA8 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | 1 | 0.97 | ||||

FC: log2 Fold Change

Cl: Classification, based on the Tuberculist website (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList/), stands for: 0, virulence, detoxification, adaptation; 1, lipid metabolism; 2, information pathways; 3, cell wall and cell processes; 7, intermediary metabolism and respiration; 9, regulatory proteins. The genes highlighted in bold are encoding enzymes containing divalent cations in their active sites. The experiment was done in triplicate.

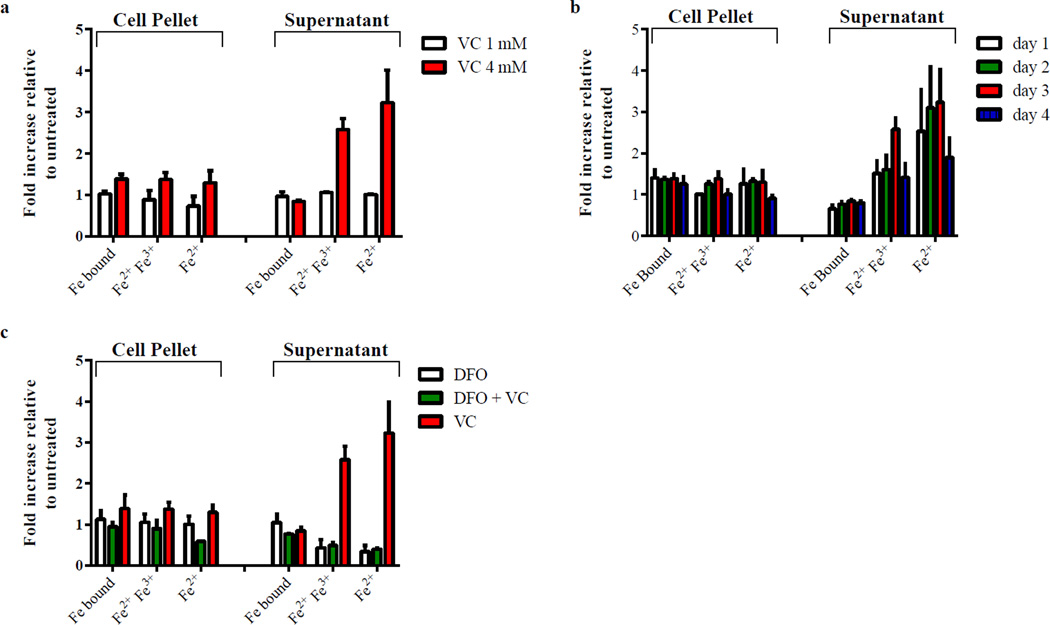

Figure 2. Vitamin C affects iron concentrations in M. tuberculosis.

Iron bound to proteins, total free iron (ferric + ferrous) and free ferrous ion concentrations were measured as described in Methods. Iron concentrations are given relative to untreated. M. tuberculosis mc26230 treated with (a) 1 mM or 4 mM vitamin C (VC) for 3 days, (b) vitamin C (4 mM) for 1, 2, 3, or 4 days, (c) DFO (100 mg/L, 152 µM), vitamin C (4 mM) or a combination of both for 3 days. The experiments were done in triplicate and the average with standard deviation is plotted.

To test whether this increased level in iron correlated with the bactericidal activity of vitamin C, M. tuberculosis H37Rv was treated with vitamin C in the presence of the iron chelator deferoxamine (DFO). M. tuberculosis was first grown with increased concentrations of DFO (from 50 to 500 mg/L) to determine the highest concentration of DFO that could be used without impairing the growth of M. tuberculosis. A concentration of 100 mg/L of DFO had minimal effect on the growth and was therefore selected. When DFO was added to M. tuberculosis H37Rv, vitamin C became bacteriostatic (Fig. 3a) and a reduction of 55 and 90% in free ferrous iron was observed in cell pellet and supernatant, respectively, compared to untreated (Fig. 2c).

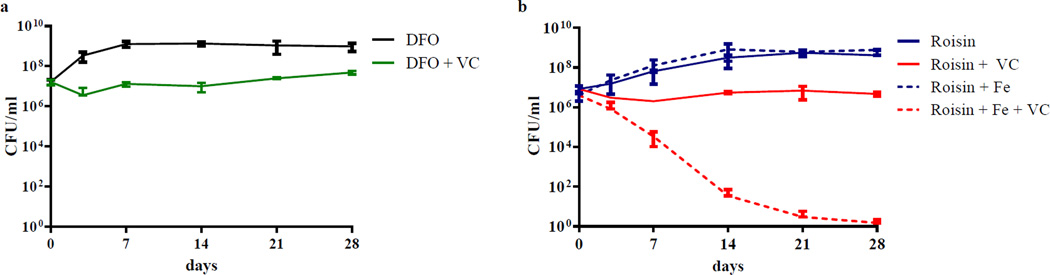

Figure 3. The effect of vitamin C is dependent on iron concentration.

(a) The iron scavenger deferoxamine (DFO) inhibits the bactericidal activity of vitamin C (VC) against M. tuberculosis H37Rv. M. tuberculosis H37Rv cultures were grown to an OD600nm of ≈0.7, diluted 1/20 and treated with with DFO (100 mg/L, 152 µM) and with or without 4 mM vitamin C. Growth was followed by plating for CFUs over time. (b) The growth of M. tuberculosis in Roisin medium with and without additional ferric ion (Fe, ferric ammonium citrate (0.04 g/l)) and treated or not with 4 mM vitamin C was followed by plating for CFUs over time. The experiments were done in triplicate and the average with standard deviation is plotted.

Further confirmation of the role of iron concentration in the bactericidal activity of vitamin C was obtained when vitamin C was found to be bacteriostatic in Roisin’s medium26 (Fig. 3b). Both Middlebrook 7H9 and Roisin’s contain ferric ion in their compositions but at different concentrations. Middlebrook 7H9 contains 80 times more ferric ion in the form of ferric ammonium citrate than Roisin. To confirm that the limited availability of ferric ion was responsible for the bacteriostatic effect of vitamin C in Roisin’s medium, ferric ammonium citrate was added to Roisin’s medium in the same amount found in Middlebrook 7H9. In Roisin’s supplemented with ferric ammonium citrate, vitamin C regained its sterilizing properties (Fig. 3b).

Vitamin C produces reactive oxygen species in M. tuberculosis

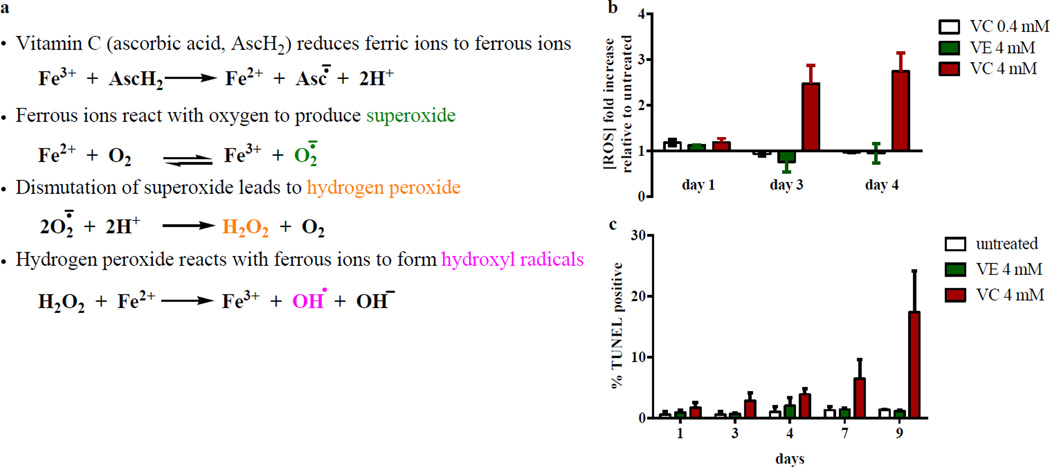

The ability of vitamin C to reduce ferric ions to ferrous ions is well known and is the basis of its pro-oxidant property. The production of ferrous ions leads to the generation of ROS (superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals) via the Harber-Weiss and Fenton reactions, which can result in DNA damage. To test if vitamin C activity against M. tuberculosis could be a consequence of this mechanism, ROS accumulation and DNA damage were measured in M. tuberculosis cultures treated with vitamin C using flow cytometry. Up to three-fold increase in total ROS was observed in M. tuberculosis treated with 4 mM vitamin C (Fig. 4a). This increase was dependent on the concentration of vitamin C; 0.4 mM vitamin C did not substantially alter total ROS concentration relative to the untreated sample. As a control, the fat-soluble antioxidant vitamin E was also tested. In contrast to vitamin C, vitamin E had lowered ROS level than the untreated samples after three days. To assess the DNA damage potentially caused by ROS accumulation, we measured DNA fragmentation in M. tuberculosis treated with vitamin C or vitamin E using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) assay (Fig. 4b). The percentage of cells with DNA breaks in M. tuberculosis treated with 4 mM vitamin C increased overtime to reach 17% to 25% after 9 days, ten-fold higher than in the untreated culture or in the culture treated with vitamin E.

Figure 4. Vitamin C increases reactive oxygen species levels and DNA damage in M. tuberculosis.

(a) M. tuberculosis mc26230 cells treated with low (0.4 mM) or high (4 mM) concentrations of vitamin C (VC) or with 4 mM of vitamin E (VE) were stained with dihydroethidium. Total reactive oxygen species concentrations were measured by flow cytometry as described in Methods and followed for 4 days. (b) The % of double stranded DNA breaks were followed over the course of 9 days in M. tuberculosis mc26230 treated with vitamin C (4 mM) or vitamin E (4 mM). The experiments were done in triplicate and the average with standard deviation is plotted.

To further test if this increase in ROS production was one of the mechanisms for the bactericidal activity of vitamin C in M. tuberculosis, cultures were treated with vitamin C in an anaerobic chamber in which the level of oxygen is kept below 0.001%. Vitamin C had no effect on M. tuberculosis viability in this condition (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5. Vitamin C acts as a pro-oxidant in M. tuberculosis.

(a) M. tuberculosis mc26230 was grown under aerobic conditions and then shifted to an anaerobic chamber (<0.0001% O2, 5% CO2, 10% H2, 85% N2). After 24 h, the culture was diluted 1/20 with hypoxic media and treated with 4 mM vitamin C (VC). Aliquots were taken at indicated time and plated to determine CFUs. Plates were incubated in an aerobic incubator. (b) The mycothiol-deficient strain H37Rv ΔmshA, grown in Middlebrook 7H9 supplemented with OADC instead of ADS, was treated with 4 mM vitamin C. Growth was followed by plating for CFUs at different times. Both experiments were done in duplicate and the average with standard deviation is plotted.

Mycothiol-deficient M. tuberculosis is extremely sensitive to Vitamin C

To examine the cell intrinsic mechanisms of protection from vitamin C-dependent killing, the effect of vitamin C on a M. tuberculosis strain deficient in mycothiol biosynthesis was also assessed. Mycothiol, N-acetyl cysteine glucosamine inositol, is the most abundant low molecular weight thiol in actinomycetes27. Its major role is to maintain a reducing environment in the cell; mycothiol mutants have been shown to be hypersensitive to oxidative stress. For example, a Mycobacterium smegmatis mshA mutant was ten times more sensitive to hydrogen peroxide than the parental strain28. M. tuberculosis ΔmshA29 which does not produce mycothiol29, was treated with 4 mM vitamin C for four weeks and CFUs were determined (Fig. 5b). A rapid 100,000-fold reduction in CFUs was observed after four days, much quicker than the wild-type strain. To confirm the hypersusceptibility of the mycothiol-deficient strain to vitamin C, the MIC was determined to be 60-fold lower in the ΔmshA strain than in wild-type M. tuberculosis (Table 1). Complementation of ΔmshA with an integrated copy of M. tuberculosis mshA restored the sensitivity to wild-type level. These results suggest that an oxidative process is part of the vitamin C bactericidal effect.

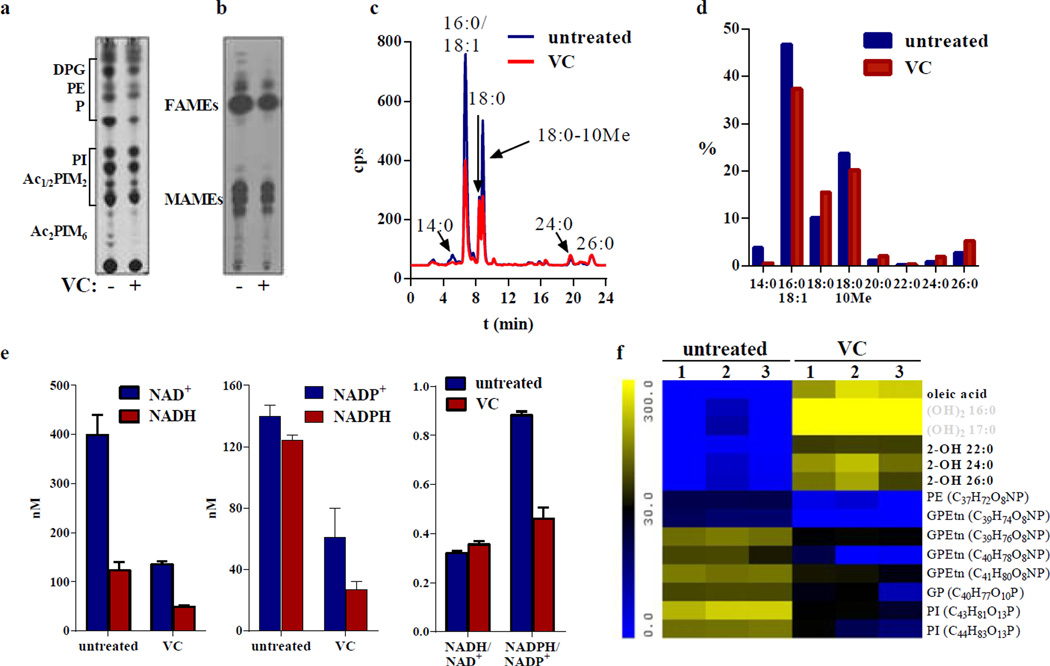

Vitamin C affects lipid biosynthesis

Lipids are among the most significant targets of oxidative damage. Oxidative damage to membrane and cell wall lipids can impair the essential function of these molecules in the maintenance of homeostasis. The transcriptional analysis revealed that the most up-regulated gene in vitamin C-treated M. tuberculosis cultures was psd encoding a phosphatidylserine decarboxylase, which converts phosphatidylserine into phosphatidylethanolamine and is involved in lipid biosynthesis. Interestingly, cell death involving ROS generation was linked to phosphatidylserine translocation on the outer membrane leaflet in E. coli, a phenotype involving psd30 and described as a marker of the programmed cell death apoptosis31. To test the effects of vitamin C on lipids, we performed a pulse-chase experiment where M. tuberculosis was treated with 4 mM vitamin C for 24 h and then labeled with 14C-acetate for 22 h. Polar lipids (Fig. 6a) and fatty acids (Fig. 6b) were analyzed by thin layer chromatography. While all lipid species were present, the total abundance of lipids in vitamin C-treated cells was lower compared to untreated cells. We observed a reduction in the fatty acid levels of vitamin C-treated cells; therefore, we analyzed the 14C-labeled fatty acid samples by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). A general decrease in total fatty acid production in vitamin C-treated samples was observed (Fig. 6c), possibly due to the inhibiting effect of vitamin C on M. tuberculosis growth. The distribution of fatty acids showed a decrease in tetradecanoic (14:0), palmitic/oleic (16:0/18:1) and tuberculostearic (18:0–10Me) acids, with increases in stearic (18:0) and longer chain fatty acids, consistent with inhibition of the Fatty Acid Synthase type II32 (FASII) (Fig. 6d). Mycobacteria possess two fatty acid synthase systems: the eukaryotic-like fatty acid synthase type I (FASI) and the prokaryotic FASII. M. tuberculosis FASI synthesizes fatty acids in a bimodal pattern (palmitic acid/hexacosanoic acid (26::0)), which are elongated by the FASII system to produce mycolic acids, long-chain (up to 90 carbons) α-alkyl β-hydroxy fatty acids, which are the major constituents of the mycobacterial cell wall.

Figure 6. Vitamin C affects mycobacterial lipids.

(a) Polar lipid analysis of M. tuberculosis H37Rv treated or not with vitamin C (4 mM) for 24 h followed by labeling with 14C-acetate for 22 h. Lipids were extracted and analyzed on thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as described in Methods. The same amount of cpm was spotted for each sample. The elution solvent used was CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (10/5/1; v/v/v). DPG, diphosphatidylglycerol; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; P, unknown phospholipids; PI, phosphatidylinositol; Ac1/2PIM2, mono- and diacyl-phosphatidylinositol dimannosides; Ac2PIM6, phosphatidylinositol hexamannosides (based on48). (b) M. tuberculosis H37Rv was treated with vitamin C (VC, 4 mM) for 24 h and then labeled with 14C-acetate for 22 h. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) and mycolic acid methyl esters (MAMEs) were extracted and analyzed by TLC as described in Methods. The same amount of cpm was spotted for each sample. (c) Radiolabeled fatty acids used for TLC (b) were saponified and derivatized to UV-absorbing esters for HPLC analysis as described in Methods. (d) Distribution of fatty acids based on the integration of the signals from the HPLC chromatograms shown in (c) 14:0, myristic acid; 16:0, palmitic acid; 18:1, oleic acid; 18:0, stearic acid; 18:0–10Me, tuberculosteric acid; 20:0, eicosanoic acid; 22:0, behenic acid; 24:0, lignoceric acid; 26:0, hexacosanoic acid (e) NADH, NAD+, NADPH, and NADP+ concentrations were measured in M. tuberculosis treated with vitamin C (4 mM) for 3 days, as described in Methods. The experiments were done in triplicate. (f) Heatmap representation of the lipids the most differentially present in the control samples (M. tuberculosis mc26230) versus the samples treated with vitamin C (4 mM) for 3 days based on Waters MarkerLynx and Extended Statistics software analysis. In bold are compounds confirmed with standards, and in grey are hypothetical compounds based on m/z and retention time. The other compounds were identified using public mycobacterial lipid databases. The heatmap represents the average of three independent experiments.

Since FASI and FASII utilize NADPH and NADH as cofactors, respectively, we tested whether the vitamin C effect on fatty acid biosynthesis was due to a decrease in cofactor availability. Although all cofactor concentrations were decreased by more than half after three days of vitamin C treatment, compared to untreated, the NADH/ NAD+ ratio stayed unchanged while the NADPH/NADP+ ratio was reduced by half in the vitamin C-treated samples due to a larger decrease in NADPH concentration (−80%, Fig. 6e), suggesting that FASI might be more affected by vitamin C than FASII. For a more accurate and sensitive analysis, total lipids from M. tuberculosis untreated and treated with vitamin C (4 mM) for three days were analyzed by ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS). Only a few lipids were differentially represented in the untreated compared to the vitamin C-treated samples (Fig. 6f), including a series of phospholipids (phosphatidylinositols (PI), phosphatidylethanolamines (PE), glycerophosphatidylethanolamines (GPEtn), and glycerophospholipids (GP)), which were found to be five- to eight-fold less abundant in the vitamin C-treated samples. Okuyama et al. showed that palmitic, hexadecenoic, octadecenoic and tuberculostearic acids were the major acids found in mycobacterial phospholipids33. Tuberculostearic acid has also been found in the mycobacterial cell wall bound to various lipids, such as glycerolipids34 or phosphoinositides35,36. This reduction in phospholipids correlates with the results of the HPLC analysis, which showed a decrease in palmitic and tuberculostearic acids. In contrast, vitamin C treatment of M. tuberculosis resulted in an accumulation of unusual hydroxylated fatty acids, which were absent in the untreated samples. The increase in free oleic acid concentration could be due to the decrease in tuberculostearic acid seen during the total fatty acid analysis (Fig. 6c and 6d), since oleic acid is the substrate for tuberculostearic acid biosynthesis. We did not detect tuberculostearic acid by UPLC-MS, suggesting that tuberculostearic acid is not present as a free fatty acid but is most likely used in glycerolipid or phospholipid biosyntheses.

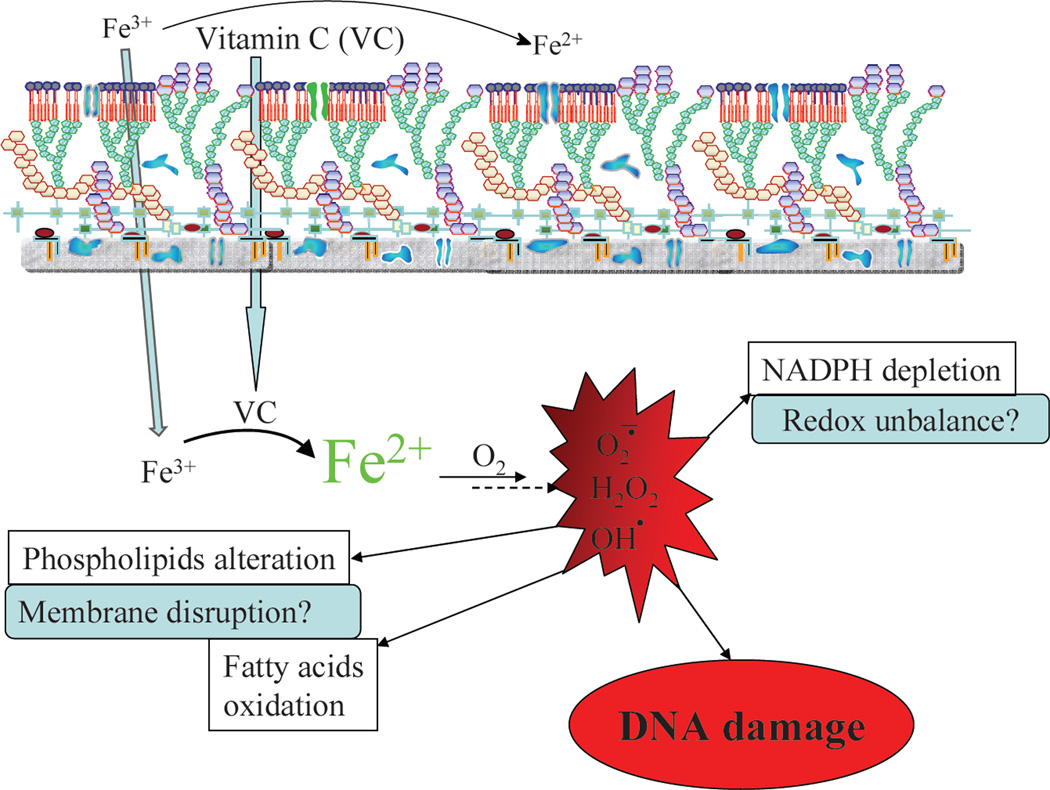

Discussion

The effect of vitamin C on various diseases has been widely described and remains controversial37. Vitamin C is known to be an anti-oxidant and a pro-oxidant25,38. The sterilizing effect of vitamin C on M. tuberculosis cultures is most likely due to its pro-oxidant activity. In this study, we demonstrated that the ability of vitamin C to sterilize M. tuberculosis cultures results from an increase in ferrous ion concentration leading to ROS production, lipid alterations, redox unbalance and DNA damage (Fig. 7). When added to M. tuberculosis in an environment that lacked oxygen or was depleted for iron, vitamin C lost its sterilization capacity.

Figure 7. Schematic representation of the mechanism of action of vitamin C against M. tuberculosis.

Vitamin C enters M. tuberculosis cells and reduces ferric ions to generate ferrous ions which, in presence of oxygen, will produce superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals via the Harber-Weiss and Fenton reactions. The production of these reactive oxygen species leads to the DNA damage, alteration of lipids and redox balance.

Recently, Taneja et al20 observed that 10 mM vitamin C induces growth arrest and a “dormant drug-tolerant” phenotype in M. tuberculosis. The authors did not observe a bactericidal activity for vitamin C, even at 10 mM. This difference with our data could be explained by the amount of ferric ion present in their media. Their experiments were carried out in Dubos media which contains 70% less ferric ions than Middlebrook 7H9. In media with low amounts of iron, it is possible that vitamin C behaves as an antioxidant rather than a pro-oxidant. In their study, the authors also observed that 10 mM vitamin C induced a dormant-like phenotype which rendered M. tuberculosis less susceptible to INH. INH is known to have no activity under non-replicating conditions. Yet in our hands, vitamin C did not reduce the activity of INH. On the contrary, the combination of a sub-lethal concentration of vitamin C (1 mM) with INH resulted in sterilization of M. tuberculosis after 4 weeks (Fig. 1b), whereas in vitro treatment of M. tuberculosis with the same amount of INH led to the outgrowth of INH-resistant mutants after 10 days. When INH was combined with vitamin C, no resistant mutants escaped the treatment. This suggests that the addition of sub-inhibitory dose of vitamin C to INH treatment could also reduce the emergence of INH-resistant mutants.

We also observed that the sterilizing effect of vitamin C was more substantial in M. tuberculosis strains deficient for mycothiol. Mycothiol is an important reducing agent in M. tuberculosis27. Its role is to detoxify and to protect the cells from oxidative damage. In a strain of M. tuberculosis that does not produce mycothiol, the bactericidal effect of vitamin C is increased sixty fold compared to a wild-type strain, resulting in the killing of 107 cells in a week. Inhibitors of the enzymes producing mycothiol have been isolated in the hope that they could lead to new drug development39,40, but a mycothiol-deficient M. tuberculosis strain has no growth defect in vitro and in vivo29. Yet, the combination of a mycothiol inhibitor and vitamin C or other pro-oxidant compound could lead to more rapid M. tuberculosis cell death than with most antibiotics used to date.

Aside from the generation of ROS species, vitamin C had also an effect on lipid biosynthesis. Vitamin C treatment resulted in the generation of free 2-hydroxylated long-chain fatty acids. This is surprising since two comprehensive analyses of total mycobacterial lipids by LC-MS did not reveal the presence of hydroxylated fatty acids in M. tuberculosis41,42, which we reconfirmed using our own lipid analysis of untreated M. tuberculosis. It is therefore unlikely that these fatty acids are produced by M. tuberculosis. Instead, these fatty acids could be generated by oxidation of 2-alkenoic acid derivatives with hydroxyl radicals from the vitamin C-derived Fenton reaction. In a study by Kondo and Kanai43, the authors demonstrated that 2-hydroxyl fatty acids (C16 and C18) were more toxic to mycobacteria than the corresponding saturated fatty acids. This accumulation of 2-hydroxy-fatty acids could therefore lead to a bactericidal event in M. tuberculosis. Furthermore, the reduction in phospholipid content observed in vitamin C-treated M. tuberculosis could affect the mycobacterial cell wall structure and, as a result, M. tuberculosis survival.

Interestingly, of several bacteria we tested, M. tuberculosis was the most sensitive to vitamin C. The eight other Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria tested were 8-to 32-times more resistant to vitamin C than M. tuberculosis, suggesting that M. tuberculosis could be more sensitive to ROS generation than other bacteria. It could also indicate that against M. tuberculosis, vitamin C has a pleiotropic effect on biological processes such as DNA synthesis, lipid synthesis, and redox homeostasis (Fig. 7). This combination of effects might be the reason why vitamin C can sterilize drug-susceptible and drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains. This is further illustrated by the fact that we were unable to obtain vitamin C-resistant mutants, which is often observed when a drug has multiple targets. This suggests that compounds that generate high levels of ROS could be useful in the development of bactericidal inhibitors of M. tuberculosis, especially if combined with inhibitors of mycothiol biosynthesis. Taneja et al. showed that 2 mM vitamin C added to M. tuberculosis-infected THP-1 cells could arrest the growth of M. tuberculosis20, indicating that vitamin C has also some activity against intracellular M. tuberculosis. We believe that the bactericidal activity of vitamin C against drug-susceptible and drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains supports further studies of the possible combination of TB chemotherapy and a high vitamin C diet in TB patients and offers a new area of research for drug design.

Methods

Bacterial strains and media

M. tuberculosis strains used in this study were obtained from laboratory stocks. Mycobacterial strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 medium (Difco, Sparks, MD) supplemented with 10% (v/v) ADS enrichment (50 g albumin, 20 g dextrose, 8.5 g sodium chloride in 1 L water), 0.2% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.05% (v/v) tyloxapol. Pantothenate (50 mg/L) was added to the medium to grow M. tuberculosis mc26230. The solid medium used was Middlebrook 7H10 medium (Difco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) OADC enrichment (Difco) and 0.2% (v/v) glycerol. Non-mycobacterial species, except Enterococcus faecalis, were grown in Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco) supplemented with ferric ammonium citrate (0.04 g/l). E. faecalis was grown in Brain Heart Infusion broth (Difco) supplemented with ferric ammonium citrate (0.04 g/l). Cultures were grown at 37°C while shaking, except for M. marinun, which was grown at 30°C. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma or Cayman Chemical unless otherwise noted.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined in 2 mL cultures in the appropriate media. The cultures were incubated while shaking for 4 weeks for slow-growing mycobacterial strains and for 2 days for the other bacteria. The MIC was determined as the concentration of vitamin C that prevented growth.

Microarray Analysis

Samples were prepared by adjusting an exponentially growing culture of M. tuberculosis H37Rv to an OD600nm ≈ 0.2 in a 50 mL volume in a 500 mL roller bottle and treating with 4 mM vitamin C. After 2 days of incubation, cells were harvested. RNA was fixed with Qiagen RNA Protect (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Cells were disrupted by mechanical lysis. RNA was purified with Qiagen RNeasy kit. Contaminating DNA was removed with Ambion TURBO DNA-free. DNA microarrays were provided by the Pathogen Functional Genomics Resource Center (PFGRC) of the J. Craig Venter Institute. Slides were scanned on a GenePix 4000A scanner. TIGR Spotfinder was used to grid and quantitate spots. TIGR MIDAS was used for Lowess normalization, standard deviation regularization, and in-slide replicate analysis with all quality control flags on and one bad channel tolerance policy set to generous. Results were analyzed in MeV with Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) considered significant at q < 0.0544.

Quantification of iron concentrations

Cultures of M. tuberculosis mc26230 were grown to an OD600nm ≈ 0.2. After addition of the appropriate chemicals (vitamin C, DFO), the cultures were incubated for up to 4 days and harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellets were washed twice with ice cold PBS, resuspended in 1 mL 50 mM NaOH with glass beads and lysed using a Fast Prep machine. To quantify bound iron, the lysate (0.1 mL) was mixed with 10 mM HCl (0.1 mL) and 0.1 mL of iron-releasing reagent (1.4 M HCl + 4.5% (w/v) aqueous solution of KMnO4; 1/1) and incubated at 60°C for two hours45. After cooling, 0.03 mL iron detection reagent (6.5 mM ferrozine + 6.5 mM neocuproine + 2.5 M ammonium acetate + 1 M ascorbic acid in water) was added and the sample absorbance was read at 550 nm. Total free iron concentration was determined as above without the addition of iron-releasing reagent. Free reduced iron concentration was measured as for the total free iron concentration without the addition of ascorbic acid in the iron-detection reagent. The iron concentrations were determined based on a standard curve obtained with increasing concentrations of ferric chloride and normalized to protein content.

Flow cytometry analysis of Reactive Oxygen Species

M. tuberculosis strain mc26230 was grown to OD600nm ≈ 1, diluted 1/5, and treated with vitamin C or vitamin E. Aliquots were taken at the indicated time points and cells were washed twice and stained with dihydroethidium. Cells were immediately used for flow cytometry analysis on a BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with the following instrument settings: forward scatter, E01 log gain; side scatter, 474V log; fluorescence (FL1), 674V log; fluorescence (FL2), 613V log; and threshold value, 52. For each sample, 100,000 events were acquired, and analysis was done by gating intact cells using log phase controls.

TUNEL assay

Aliquots of mycobacterial cells were removed from M. tuberculosis mc26230 cultures treated with the appropriate compounds and washed once, then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were centrifuged, permeabilized for 2 min on ice, rewashed, and then resuspended in 100 µL of TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling) reaction mix from the in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). After an incubation period of 1 h at 37°C in the dark, the reaction mixture was washed once and kept at 4°C until analysis. Analysis was done by flow cytometry, using the instrument settings described above, by gating intact cells using gamma-irradiated cell positive controls, and cells incubated with label solution only (no terminal transferase) for negative controls. 100,000 events were acquired per sample. Cells positive for TUNEL staining were quantified as percentages of total gated cells.

Polar lipid analysis

M. tuberculosis cultures (OD600nm = 0.2) were treated with vitamin C (4 mM) for 24 h and then labeled with 14C-acetate (1 µCi/ml) for 22 h. Cell pellets were washed with PBS, autoclaved, and extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (2/1). The organic phases were dried, resuspended in CHCl3/MeOH (2/1; 0.2 ml) and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC)46. Radiolabeled species were detected by autoradiography. The autoradiograms were obtained after exposure at −80°C for 2 days on X-ray film.

Fatty acid analysis

M. tuberculosis cultures (OD600nm = 0.2) were treated with vitamin C (4 mM) for 24 h and then labeled with 14C-acetate (10 µCi in 10 mL culture) for 22 h. Cell pellets were treated with 20% tetrabutylammonium hydroxide at 100°C overnight. After cooling, the suspensions were methylated with methyl iodide (0.1 ml) in dichloromethane (2 ml) for 1 h. The organic phase was washed twice and dried47. Fatty acids were analyzed by TLC (hexane/ethyl acetate; 95/5; 3 elutions). Radiolabeled species were detected by autoradiography as described above. The samples were then saponified with 10% potassium hydroxide in methanol for 2 h at 85°C and derivatized to UV-absorbing p-bromophenacyl esters using the p-bromophenacyl ester kit from Grace Davison (Deerfield, IL). High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of the radiolabeled p-bromophenacyl fatty acid esters was conducted on a Hewlett-Packard model HP1100 equipped with an IN/US β-RAM model 2B flowthrough radioisotope beta-gamma radiation detector (IN/US Systems, Inc., Tampa, Fla.). A reverse-phase C18 column (4.6 by 150 mm; 3-mm column diameter; Alltima) was used. The column temperature was set at 45°C and the wavelength at 260 nm. The mobile phase was acetonitrile and the flow rate was 1 mL/min for the first 6 min, followed by a linear increase to 2 mL/min in 1 min and then set at 2mL/min for another 17 min. The 14C-labeled fatty acid esters were detected using the scintillator In-FlowTM ES (IN/US Systems). The chromatograms’ peaks were identified by comparison with chromatograms of p-bromophenacyl fatty acid ester standards.

Cellular concentrations of cofactors

M. tuberculosis cultures (OD600 nm ≈ 0.15) were treated with vitamin C (4 mM) for 3 days. 15 ml of each culture was treated with 0.2N HCl (0.75ml, NAD+/NADP+ extraction) or 0.2N NaOH (0.75 ml, NADH/NADPH extraction) at 50°C for 10 min. The samples were neutralized, centrifuged, and the supernatants were frozen until ready to use. The cofactors concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at 570 nm by measuring the rate of conversion of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (4.2 mM) and phenazine ethosulfate (16.6 mM) by alcohol dehydrogenase (5 units) in the presence of ethanol (20 µl)44. NADP+ and NADPH concentrations were measured as for NAD+ and NADH, using glucose-6-phosphate (4 g/L) instead of ethanol and glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (0.5 unit) instead of alcohol dehydrogenase.

Analysis of total lipids by UPLC-MS

M. tuberculosis mc26230 (10 mL culture, OD600nm ≈ 0.1) was treated with vitamin C (4 mM) and incubated while shaking for 3 days. The cultures were centrifuged and the cell pellets were washed once with PBS. Lipids were extracted with chloroform/methanol (2/1, v/v; 3 mL) overnight at room temperature while rotating, centrifuged and the supernatants were removed and evaporated to dryness under nitrogen. The lipid residues were dissolved in isopropanol/acetonitrile/water (2:1:1, v/v; 0.75 mL) and analyzed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC, Acquity, Waters) coupled with a quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometer (Synapt G2, Waters). The UPLC column was an ACQUITY BEH C18 Column. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min, the column temperature was set at 55 °C. The mobile phases were: A, acetonitrile/water (60/40) with 0.1% forming acid; B, acetonitrile/isopropanol (10/90) with 0.1% formic acid. The conditions used for the UPLC were: 0 min, 60% A; 2 min, 57% A (curve 6); 2.1 min, 50% A (curve 1); 12 min, 46% A (curve 6); 12.1 min, 30% A (curve 1); 18 min, 1 % A (curve 6); 18.1 min, 60% A (curve 6); 20 min, 60% A (curve 1). The MS conditions were: acquisition mode, MSE; ionization mode, ESI (+/−); capillary voltage, 2 kV (positive), 1 kv (negative); cone voltage, 30 V; desolvation gas flow, 900 L/h; desolvation gas temperature, 550 °C; source temperature. 120 °C, acquisition range, 100 to 2000 m/z with a scan time of 0.5 s. Leucine enkephalin (2 ng/µL) was used as lock mass. Data generated from the experiments were processed and analyzed by the Waters MarkerLynx software, which integrates, aligns MS data points and converts them into exact mass retention time pairs to build a matrix composed of retention time, exact mass m/z, and intensity pairs. Waters Extended statistics software was used to create a two-class OPLS-DA model to identify the mass/retention time pairs that were the most differentially abundant between untreated and vitamin C-treated samples. The noise level was 3% in both positive and negative mode. Ions were identified using published databases (http://www.lipidmaps.org/tools/ms/LMSD_search_mass_options.php, http://www.brighamandwomens.org/research/depts/medicine/rheumatology/labs/moody/default.aspx; http://metlin.scripps.edu/). When standards were commercially available, identification was confirmed by comparing retention time accurate mass, and MS/MS data between standards and samples.

Acknowledgements

W.R.J. acknowledges generous support from the NIH Centers for AIDS Research Grant (CFAR) AI-051519 at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant AI26170 (to W.R.J). We thank the Montefiore clinical microbiology laboratory for providing the non-mycobacterial species.

Footnotes

Author contributions

C.V. performed and analyzed the data from the growth curves, iron concentrations measurements, and lipid analyses, and wrote the paper. T.H. performed and analyzed the data from the ROS and DNA break measurement experiments. B.W. performed and analyzed the data from the transcriptional analyses and the iron concentration experiments. W.R.J. contributed to the design of the study, data analysis, data interpretation, and provided grant support.

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Accesion codes

The array data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE42293.

References

- 1.Colijn C, Cohen T, Ganesh A, Murray M. Spontaneous emergence of multiple drug resistance in tuberculosis before and during therapy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkon JB, et al. The emergence of isoniazid-resistant cultures in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis during treatment with isoniazid alone or isoniazid plus PAS. Bull. World Health Organ. 1964;31:273–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillespie SH. Evolution of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: clinical and molecular perspective. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:267–274. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.2.267-274.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keren I, Wu Y, Inocencio J, Mulcahy LR, Lewis K. Killing by bactericidal antibiotics does not depend on reactive oxygen species. Science. 2013;339:1213–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1232688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Imlay JA. Cell death from antibiotics without the involvement of reactive oxygen species. Science. 2013;339:1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1232751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Wierzbowski J, Cottarel G, Collins JJ. Mistranslation of membrane proteins and two-component system activation trigger antibiotic-mediated cell death. Cell. 2008;135:679–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foti JJ, Devadoss B, Winkler JA, Collins JJ, Walker GC. Oxidation of the guanine nucleotide pool underlies cell death by bactericidal antibiotics. Science. 2012;336:315–319. doi: 10.1126/science.1219192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haber F, Weiss J. The catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxidase by iron salts. Proc. Royal Soc. Lond. A. 1934;147:332–351. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenton H. Oxidation of tartaric acid in the presence of ion. J. Chem. Soc. 1894;23:899–910. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burkitt MJ, Gilbert BC. Model studies of the iron-catalysed Haber-Weiss cycle and the ascorbate-driven Fenton reaction. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1990;10:265–280. doi: 10.3109/10715769009149895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodges RE, Baker EM, Hood J, Sauberlich HE, March SC. Experimental scurvy in man. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1969;22:535–548. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/22.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormick WJ. Vitamin C in the prophylaxis and therapy of infectious diseases. Arch. Pediatr. 1951;68:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padayatty SJ, et al. Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation of its role in disease prevention. J. Am Coll. Nutr. 2003;22:18–35. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauling L. Vitamin C the common cold and the flu. San Francisco: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone I. The Healing Factor: Vitamin C Against Disease. New York: Grosset and Dunlap; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McConkey M, Smith DT. The Relation of Vitamin C Deficiency to Intestinal Tuberculosis in the Guinea Pig. J. Exp. Med. 1933;58:503–512. doi: 10.1084/jem.58.4.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pichat P, Reveilleau A. Bactericidal action for Koch's bacilli of massive doses of vitamin C; comparison of its action on a certain number of other microbes. Ann. Inst. Pasteur (Paris) 1950;79:342–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pichat P, Reveilleau A. Comparison between the in vivo and in vitro bactericidal action of vitamin C and its metabolite, and ascorbic acid level. Ann. Inst. Pasteur (Paris) 1951;80:212–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taneja NK, Dhingra S, Mittal A, Naresh M, Tyagi JS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcriptional adaptation, growth arrest and dormancy phenotype development is triggered by vitamin C. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narwadiya SC, Sahare KN, Tumane PM, Dhumne UL, Meshram VG. In vitro anti-tuberculosis effect of vitamin C contents of medicinal plants. Asian J. Exp. Biol. Sci. 2011;2:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vilcheze C, Jacobs WR., Jr The combination of sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and isoniazid or rifampin is bactericidal and prevents the emergence of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5142–5148. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00832-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ioerger TR, et al. Genome analysis of multi- and extensively-drug-resistant tuberculosis from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez GM, Voskuil MI, Gold B, Schoolnik GK, Smith I. ideR, An essential gene in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of IdeR in iron-dependent gene expression, iron metabolism, and oxidative stress response. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:3371–3381. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3371-3381.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Podmore ID, et al. Vitamin C exhibits pro-oxidant properties. Nature. 1998;392:559. doi: 10.1038/33308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beste DJ, et al. Compiling a molecular inventory for Mycobacterium bovis BCG at two growth rates: evidence for growth rate-mediated regulation of ribosome biosynthesis and lipid metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:1677–1684. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1677-1684.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newton GL, Buchmeier N, Fahey RC. Biosynthesis and functions of mycothiol, the unique protective thiol of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008;72:471–494. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00008-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton GL, et al. Characterization of Mycobacterium smegmatis mutants defective in 1-d-myo-inosityl-2-amino-2-deoxy-alpha-d-glucopyranoside and mycothiol biosynthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;255:239–244. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vilchèze C, et al. Mycothiol biosynthesis is essential for ethionamide susceptibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;69:1316–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langley KE, Hawrot E, Kennedy EP. Membrane assembly: movement of phosphatidylserine between the cytoplasmic and outer membranes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1982;152:1033–1041. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.3.1033-1041.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dwyer DJ, Camacho DM, Kohanski MA, Callura JM, Collins JJ. Antibiotic-induced bacterial cell death exhibits physiological and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 2012;46:561–572. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vilchèze C, et al. Inactivation of the inhA-encoded fatty acid synthase II (FASII) enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase induces accumulation of the FASI end products and cell lysis of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:4059–4067. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.4059-4067.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okuyama H, Kankura T, Nojima S. Positional distribution of fatty acids in phospholipids from Mycobacteria. J. Biochem. 1967;61:732–737. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a128607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ter Horst B, et al. Asymmetric synthesis and structure elucidation of a glycerophospholipid from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:1017–1022. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M001982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Besra GS, Morehouse CB, Rittner CM, Waechter CJ, Brennan PJ. Biosynthesis of mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:18460–18466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilleron M, et al. Acylation state of the phosphatidylinositol mannosides from Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette Guerin and ability to induce granuloma and recruit natural killer T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:34896–34904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naidu KA. Vitamin C in human health and disease is still a mystery? An overview. Nutr. J. 2003;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frei B, England L, Ames BN. Ascorbate is an outstanding antioxidant in human blood plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1989;86:6377–6381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newton GL, Buchmeier N, La Clair JJ, Fahey RC. Evaluation of NTF1836 as an inhibitor of the mycothiol biosynthetic enzyme MshC in growing and non-replicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:3956–3964. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Metaferia BB, et al. Synthesis of natural product-inspired inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mycothiol-associated enzymes: the first inhibitors of GlcNAc-Ins deacetylase. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:6326–6336. doi: 10.1021/jm070669h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Layre E, et al. A comparative lipidomics platform for chemotaxonomic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:1537–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sartain MJ, Dick DL, Rithner CD, Crick DC, Belisle JT. Lipidomic analyses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on accurate mass measurements and the novel "Mtb LipidDB". J. Lipid Res. 2011;52:861–872. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M010363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kondo E, Kanai K. The relationship between the chemical structure of fatty acids and their mycobactericidal activity. Jpn J. Med. Sci. Biol. 1977;30:171–178. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.30.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vilchèze C, Weinrick B, Wong KW, Chen B, Jacobs WRJ. NAD+ auxotrophy is bacteriocidal for the tubercle bacilli. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;76:365–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riemer J, Hoepken HH, Czerwinska H, Robinson SR, Dringen R. Colorimetric ferrozine-based assay for the quantitation of iron in cultured cells. Anal. Biochem. 2004;331:370–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Besra GS. Preparation of cell wall fractions from mycobacteria. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vilchèze C, Jacobs WRJGS. Isolation and analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mycolic acids. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc10a03s05. Chapter 10, Unit 10A.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waddell SJ, et al. Inactivation of polyketide synthase and related genes results in the loss of complex lipids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;40:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]