Abstract

In 2011, the Division of Violence Prevention (DVP) within CDC's Injury Center engaged an external panel of experts to review and evaluate its research and programmatic portfolio for sexual violence (SV) prevention from 2000 to 2010. This article summarizes findings from the review by highlighting DVP's key activities and accomplishments during this period and identifying remaining gaps in the field and future directions for SV prevention. DVP's SV prevention work in the 2000s included (1) raising the profile of SV as a public health problem, (2) shifting the field toward a focus on the primary prevention of SV perpetration, and (3) applying the public health model to SV research and programmatic activities. The panel recommended that DVP continue to draw attention to the importance of sexual violence prevention as a public health issue, build on prior investments in the Rape Prevention and Education Program, support high-quality surveillance and research activities, and enhance communication to improve the link between research and practice. Current DVP projects and priorities provide a foundation to actively address these recommendations. In addition, DVP continues to provide leadership and guidance to the research and practice fields, with the goal of achieving significant reductions in SV perpetration and allowing individuals to live to their full potential.

Sexual violence (SV) is a major public health problem in the United States and worldwide. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines SV as including any attempted or completed sexual act, sexual contact, or noncontact sexual behavior in which the victim does not consent or is unable to consent or refuse.1 About 1 in 5 women and 1 in 71 men in the United States have experienced rape or attempted rape in their lifetimes.2 In addition, nearly half (44.6%) of women and one fifth (22.2%) of men have experienced other forms of SV, such as being made to penetrate someone else, sexual coercion, unwanted sexual touching, and noncontact unwanted sexual experiences.2 SV has serious consequences for victims' physical and mental health, including physical injury from the assault and an increased risk of depression, anxiety, suicidal behavior, substance abuse, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and gynecologic or pregnancy complications.3,4 Because of the public health risk posed by SV, the Division of Violence Prevention (DVP) within CDC's National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (Injury Center) is committed to advancing programmatic and research activities to prevent SV. CDC's Injury Center initiated an objective peer review process in 2011 to reflect on DVP's work in SV prevention during the last decade (2000–2010). The current article summarizes findings from this review by highlighting DVP's key activities and accomplishments during this period and identifying remaining gaps in the field and future directions for SV prevention.

Looking Back: CDC's Work on SV Prevention, 2000–2010

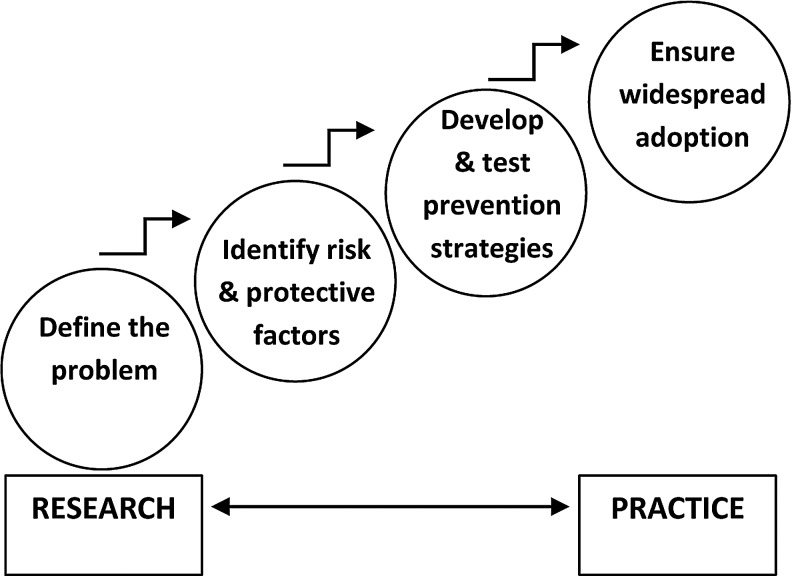

As a division within a federal public health agency, CDC's DVP has a unique role in contributing to the prevention of SV. DVP helps set the domestic public health agenda for research and programmatic efforts to prevent SV and provides guidance and information to state and local health departments, communities, and other entities about the nature of the problem and its prevention. DVP's work focuses on primary prevention, or preventing violence before it occurs, and it emphasizes reducing rates of SV at the population level rather than focusing solely on the health or safety of the individual. In addition, through the Rape Prevention and Education (RPE) Program, DVP provides funding and technical assistance to all states and U.S. territories and jurisdictions to implement SV prevention strategies. DVP's work is guided by the overarching framework of the public health model (Fig. 1), which identifies four interactive steps that guide prevention research and practice: (1) define and monitor the problem through surveillance, (2) identify risk and protective factors, (3) develop and evaluate prevention strategies, and (4) ensure widespread adoption of effective approaches.5,6

FIG. 1.

The public health approach to prevention.

DVP received its first congressional appropriation for SV and intimate partner violence (IPV) in 1994 with passage of the landmark Violence Against Women Act. During the 1990s, SV prevention activities occurred primarily within the context of IPV prevention, an emerging research area for DVP. Starting in 2000, DVP's work in SV prevention increased significantly after Congress appropriated an additional $1.2 million to support SV and IPV research. Around the same time, Congress designated programmatic responsibility for the RPE Program to DVP. Today, the RPE Program accounts for the bulk of DVP's work in SV prevention.

In late 2010, CDC's Injury Center initiated a structured review and assessment of DVP's contributions to the SV field during the decade following these increases in funding and programmatic changes (2000–2010) to identify key accomplishments, remaining challenges, and directions for future efforts in the primary prevention of SV. (As a matter of policy, CDC periodically subjects all research, scientific, and programmatic efforts to external peer review. CDC: Peer Review of Research and Scientific Programs, CDC-GA-2002-09. 2008. Available at www.cdc.gov/maso/pdf/PeerReview.pdf ) The Injury Center worked with an external contractor to gather information on DVP's portfolio of research and programmatic activities. This included information from archival documents and peer-reviewed publications, DVP-funded research grants and cooperative agreements, aggregate data from grantee reports, highlights of prevention plans from funded programs, and information on DVP's institutional and funding history. The contractor also conducted interviews with individuals involved in DVP's SV prevention work, including state grantees, SV prevention researchers, and DVP staff. An objective review panel, including researchers, advocates, and state public health officials with expertise in SV prevention, was convened in September 2011 to identify key successes and gaps and propose recommendations for future work. Reviewers were specifically asked to consider DVP's contributions in terms of building the SV prevention infrastructure, surveillance and research activities, connecting research and practice, and providing leadership within the SV prevention field. The external panel reviewed the material and met with staff from CDC's Injury Center, including DVP staff, to provide feedback and recommendations. Although DVP is actively engaged in international efforts to prevent SV (See www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/globalviolence for more information), this review focused only on domestic research and programmatic activities.

The current article provides a summary of DVP's key activities and accomplishments from 2000 to 2010, as identified in the course of this review. For the purposes of this summary, we grouped this SV prevention work into the following three overarching activities: (1) increasing the profile of SV as a public health problem, (2) shifting the field toward a focus on the primary prevention of SV perpetration, and (3) applying the public health model to research and programmatic activities in the prevention of SV.

Raising the profile of SV as a public health problem

Several influential articles published by DVP scientific staff in the early 2000s introduced the research and practice fields to ways in which the public health model could be applied to the prevention of SV and related health consequences in the United States, thus improving the visibility of SV as a significant but neglected public health problem.7–9 The identification of SV as a threat to public health, rather than solely a criminal justice issue, provided new and critical opportunities for the field to inform the investment in prevention work to complement (and reduce the need for) efforts to incarcerate offenders and provide services to survivors. An early and ongoing goal of DVP involved building the evidence base for and increasing awareness of the impact of SV on population-level health and the potential value of using public health strategies to prevent it. Interviewees for this review commented on the impact of DVP's work on the field, with one coalition leader stating, “We would not be talking about SV as a public health issue if it weren't for [DVP's] leadership.”

Consistent with the public health model, a major thrust of DVP's early work in SV prevention focused on publishing uniform definitions and recommended data elements for SV1 and the development of useful national data10,11 that could capture the nature, scope, and impact of SV in the United States. For example, the National Violence Against Women Survey, jointly funded and conducted by DVP with the National Institute of Justice in 1995 and 1996, provided lifetime and 12-month prevalence estimates for rape and attempted rape.11 These data provided DVP and the field with the first consistent and reliable estimates of the nature and scope of SV in the United States, supporting efforts to raise awareness of the impact of SV and the need for prevention. Also, in 1999, DVP convened a panel of experts to begin developing a standard definition of SV to increase consistency in the way SV is defined and enable better monitoring of the problem and comparisons across jurisdictions. This work culminated in the widely disseminated 2002 publication, Sexual Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements (version 1.0).1

DVP-led survey efforts continued through the 2000s. For instance, CDC's Injury Center collected rape prevalence data from 2001 to 2003 with items included on the Second Injury Control and Risk Survey, a national random digit dial telephone interview that collected data on a wide range of intentional and unintentional injury topics, such as smoke alarm use, helmet use, and water safety, as well as injuries related to interpersonal violence, sexual violence, and suicide.12 To provide comparable state-level data across several states, DVP also developed an optional SV module for CDC's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).13 Together, these surveys provided evidence of the high rates of victimization and the serious physical and psychologic health problems associated with SV behaviors.

To address the need for an ongoing surveillance system that would provide national and state-level data for prevention planning, DVP worked with partners and external experts to develop a national survey to describe the prevalence and characteristics of SV, stalking, and IPV. This work culminated in the launch of the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) in 2010 (for more information, www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/NISVS). NISVS provides: (1) annual surveillance data using DVP's uniform definitions, (2) the ability to monitor trends, and (3) improved data quality, with additional details that capture the nature, impact, severity, and consequences of SV and IPV experienced by men and women in the United States. NISVS provides both national and state-level estimates of rape victimization and other forms of SV, such as being made to penetrate someone else, sexual coercion, unwanted sexual contact, and noncontact unwanted sexual experiences. The first NISVS report based on data collected in 2010 from a sample of >18,000 was released in 2011.2 DVP has committed to implementing NISVS as an ongoing annual survey. The external panel highlighted the establishment of the NISVS system as critically important for addressing the field's need for information about the prevalence and consequences of SV and state-specific data for use in planning and evaluation.

Shifting the focus toward primary prevention of perpetration

A hallmark of the public health model is its focus on primary prevention. Primary prevention (in contrast to secondary or tertiary prevention) aims to prevent negative health outcomes before they occur rather than seeking to ameliorate the effects or prevent recurrence. Consistent with this public health approach, DVP's unique contribution to the field since its inception has been a commitment to primary prevention. In the early 2000s, DVP identified a need to further concentrate research and programmatic efforts on the prevention of SV perpetration specifically, rather than focusing on victimization prevention. This represented a paradigmatic shift for the practice field. Until then, advocates' efforts were largely devoted to the provision of victim services and support.14 Further, although interest in primary prevention strategies had increased among researchers and program developers, many SV prevention programs used victimization prevention strategies, such as rape avoidance or resistance training for women.8,15,16 Although these strategies have showed promise in reducing the risk of victimization for individual women who receive the training,17 DVP recognized that this approach would have limited impact on rates of SV, as such strategies do not reduce the number of potential perpetrators or address the social norms that allow SV to flourish.8,18 In addition, they place the burden for preventing SV on potential victims. DVP's change in focus toward work supporting the primary prevention of perpetration is evident in the trajectories of its programmatic and research activities during this period and in its current work on SV prevention.

Changing focus in the RPE Program

The RPE Program, established by the 1994 Violence Against Women Act, supports SV prevention efforts conducted by health departments, state sexual assault coalitions, rape crisis centers, and other community-based organizations in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. territories and jurisdictions. When programmatic responsibility for RPE was designated to DVP in 2001, SV prevention efforts were mainly low-dosage, individual-level strategies that focused on awareness and information about victim services.19 Since 2001, DVP has shifted the program's focus to emphasize the primary prevention of first-time perpetration and victimization with strategies grounded in the public health approach and the best available science. This refined focus was articulated in the 2006 Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) for RPE, which included an explicit emphasis on primary prevention and community change strategies as well as the development of a state SV prevention plan. To facilitate this major change in RPE's mission and work, DVP has focused its efforts over the past decade on providing training and technical assistance to RPE grantees and building state capacity to engage in prevention planning, implementation, and evaluation. In addition to annual meetings, monthly phone calls, and regular site visits with RPE grantees, DVP funds two national resource centers (National Sexual Violence Resource Center: www.nsvrc.org; Prevent Connect: www.preventconnect.org) and the National Sexual Violence Prevention Conference to provide prevention-related support and training to RPE grantees and others doing SV prevention work.

In 2005, DVP launched the EMPOWER Program as a capacity-building demonstration project designed to improve the ability of a subset of DVP's RPE-funded states to use a public health approach for the primary prevention of SV. DVP entered into two 3-year cooperative agreements (2005–2012) with six RPE-funded states—Colorado, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Jersey, North Carolina, and North Dakota—that were selected based on their demonstrated readiness to incorporate primary prevention into their state SV work through public health program planning and evaluation. With intensive training and technical assistance from DVP, EMPOWER states used an empowerment evaluation approach to develop data-driven, comprehensive state SV prevention programs. The states also developed evaluation and sustainability plans that served as the blueprint for building state system and local organization capacity for prevention and evaluation. Lessons learned from the EMPOWER program are currently shaping future plans in the RPE Program, DVP, and the SV field about essential factors for building and maintaining capacity.

Trends in research funding for SV prevention

DVP's focus on the primary prevention of perpetration also influenced the research landscape for SV. In 2000, DVP issued the first R01 research grant announcements that explicitly included SV in the funding priorities. Since then, SV has been included in the R01 grant announcement each year. In 2007, DVP released its first SV-specific FOA to support etiologic research examining the links between bullying and SV perpetration. With the practice field and RPE grantees eager for more information on what works to prevent SV, DVP released a second SV-specific FOA in 2009 to support evaluation trials of two SV primary prevention programs. In total, DVP funded 27 research projects from 2000 to 2010 through grants and cooperative agreements that included a focus on SV, resulting in the availability of > $19 million dollars in federal funding. This funding represented a sizable addition to the limited pool of federal funding available for SV research at the time,20 filling a critical need in the field and helping support and enhance the development of an SV research infrastructure.

In addition to overall increases in DVP research funding for SV, the type of research supported by the division during this period changed over time. Specifically, two patterns emerged: projects targeting victimization declined (with none funded after 2007), and projects targeting perpetration and bystander approaches increased. The increased investment in bystander approaches is consistent with DVP's more recent efforts to move the field beyond solely individual-level strategies to address other levels of the social ecology, including peers, school climate, adult role models, and parents. For example, DVP funded an effectiveness study of the Coaching Boys into Men program in 2009, which was designed to prepare high school athletic coaches to serve as positive role models for male students by talking about respect in relationships, gender equitable attitudes, and how to intervene as a bystander.21

Increased staffing

The enhanced and deliberate focus on primary prevention of SV perpetration and the increased investments in etiologic and evaluation research were paralleled by a growing capacity for conducting SV prevention work within DVP. Between 1994 and 2010, the number of DVP staff whose work focused primarily on SV or IPV increased from 8 to 25. DVP staff published a total of 57 SV-related peer-reviewed articles, an average of more than 5 publications per year, between 2000 and 2010. DVP's contributions to the SV literature during this period built a compelling argument for viewing SV as a public health issue and provided both the rationale and theory needed to guide primary prevention of SV perpetration. For example, key articles by DVP introduced the public health approach to SV,7,22 engaged the sex offender management field in SV prevention,8 reviewed the current literature to disseminate findings and foster continued research progress,23 shifted the field toward a focus on preventing first-time male perpetrators,24 and identified promising new domains for risk factor research.25

Applying the public health model to SV prevention

A third unique and overarching DVP activity during this period was to engage in research and programmatic work across the public health model to reduce the incidence and negative consequences of SV. The steps of the public health model, from surveillance and etiologic research to the identification and dissemination of effective prevention strategies, often are represented as progressive stages with information moving primarily in one direction. In practice, however, these steps function as an interactive feedback loop, with the flow of information between research and practice moving in both directions (Fig. 1). Ensuring progress within each step of the model while also facilitating transfer of knowledge between the research and practice fields has been a cornerstone of DVP's work. Two examples highlight ways in which knowledge and experience in the field have shaped the research activities of DVP, with that research, ultimately, also impacting the field.

Implementing and evaluating Green Dot

The Green Dot program, developed and first implemented at the University of Kentucky (UK), employs an active bystander intervention model with the premise that acts of violence (red dots on an epidemiologic map) can be replaced with green dots denoting behaviors and attitudes that promote safety and intolerance for violence.26 The progress of this program reflects the iterative link between research and practice and how each plays a role in enhancing prevention. Based on initial evidence of effectiveness in increasing active bystander behaviors at the college level, the DVP-funded Kentucky EMPOWER State Planning Team identified Green Dot as a promising strategy for their SV prevention efforts and worked closely with UK researchers to adapt the program for high school populations. Green Dot was implemented by all 13 RPE-funded rape crisis centers in the state of Kentucky in 2010 with RPE funding. Around the same time, UK researchers in collaboration with the Kentucky Association of Sexual Assault Programs (KASAP) successfully competed for funding from DVP to complete a rigorous, statewide evaluation of the effectiveness of the Green Dot high school program for preventing SV. Results from this evaluation are expected by 2015. If the ongoing evaluation provides evidence of positive program effects, the formative work of the Kentucky EMPOWER Team and KASAP to develop a detailed implementation plan for Green Dot will provide a model for disseminating and implementing the program through other state RPE programs.

Exploring links between bullying and SV

With few evidence-based programs available for SV prevention, some RPE grantees began implementing bullying prevention programs in middle and high schools in the early 2000s as an alternative strategy for preventing SV. DVP's recognition of this practice sparked a series of research projects that investigated the links between bullying and SV. First, DVP completed a literature review examining the conceptual and empirical associations between bullying and male SV perpetration.27 This review found that most of the factors associated with bullying perpetration were also associated with SV perpetration, suggesting that the two forms of violence share many risk and protective factors and may share common developmental pathways. In an effort to better understand these etiologic links between bullying and SV and inform future prevention strategies, DVP funded a longitudinal study in 2007 investigating the association between bullying and concurrent and subsequent SV perpetration among middle school students. Findings from this study were shared with RPE grantees to inform their prevention efforts and suggest ways that they might adapt existing bullying and SV interventions.28,29 In 2009, DVP built on this foundational work by funding a rigorous evaluation of Second Step: Student Success Through Prevention, a middle school bullying prevention program, to examine effects on SV behavior, including sexual harassment, homophobic teasing, and SV in dating relationships. Findings from this 3-year study (expected in 2013) will also be shared with RPE grantees.

Moving Forward: Current and Future Directions in DVP

The external peer review panel, convened by CDC's Injury Center to review DVP's portfolio of SV research and programmatic activities from 2000 to 2010, identified several strengths of DVP's work in this period. Among the many contributions highlighted by the panel were DVP's leadership and effectiveness in moving the progression of surveillance and research activities from victimization to perpetration. The peer review panel also noted that DVP has been consistently responsive to the field and has demonstrated willingness to change emphases and reprioritize based on lessons learned. RPE grantees, in particular, have made major strides in implementing data-informed primary prevention strategies as a result of DVP's work on more refined definitions, use of the ecologic model, and focus on primary prevention of perpetration. In many cases, RPE funds have also allowed for the establishment of much needed infrastructure in states and coalitions. Panelists expressed appreciation for DVP's investment in both research-to-practice and practice-to-research approaches.

The external review panel was impressed with the breadth of DVP's SV prevention portfolio overall but also noted several limitations and remaining gaps. The panelists made several recommendations to improve and expand DVP's SV prevention work in the future. In offering these recommendations, the panel acknowledged the challenging economic environment in which CDC's Injury Center and state and local entities operate and expressed the value and importance of maintaining a balance of both research and programmatic activities in the face of these constraints. Four overarching recommendations from the panel are summarized below along with examples of current work in DVP that address some of the gaps identified. (An executive summary with additional recommendations made by the panel is available from the authors upon request. DVP's current investments reflect the CDC Injury Research Agenda for 2009–2018, available at www.cdc.gov/injury/ResearchAgenda, which identifies research areas for SV as well as other forms of violence and unintentional injury.)

Elevate importance of SV prevention

The panel emphasized the continued need to increase awareness of SV as a significant public health problem in the eyes of the general public and the public health community, including identifying it as a priority area for CDC and other federal agencies. DVP is actively addressing several specific suggestions the panel offered for elevating awareness and action for SV prevention. For example, SV prevention is part of the Injury Center's new focus area on violence against children and youth (more information about this focus area and related efforts to collect and share data about SV and to implement and evaluate SV prevention strategies is available at www.cdc.gov/injury/about/focus-cm.html). DVP is also working to convey accurate data in a timely fashion, more fully describing the connections between SV and other health issues and disparities, and providing states with the data and tools needed to help them prioritize SV at the state level. For example, the recently released NISVS report provided prevalence estimates from 2010 and described the elevated risk of headaches, chronic pain, difficulty sleeping, activity limitations, poor physical health, and poor mental health among victims of rape or stalking by any perpetrator or physical violence by an intimate partner. DVP is also working toward development of the first-ever national estimates of the individual and societal costs associated with SV incidence. These cost estimates will provide much-needed information about the economic impact of SV in the United States and the potential cost-effectiveness of preventive interventions.

Build on RPE investment

Because a tremendous amount of resources is invested in local and state prevention work through the RPE Program, the panel identified a need for more information about and evaluation of those activities. The panel also emphasized the critical interest in maintaining and increasing RPE funding over time, noting that the current level of funding, which is distributed based on population size, is insufficient for states to complete the scope of work required by the statute, particularly in less-populated states. To continue to build the capacity of RPE grantees, the panel recommended that DVP provide more focused technical assistance. DVP addresses these recommendations in a recently released 1-year RPE FOA. The new FOA recognizes that many RPE Programs have limited evaluation capacity and that the population-based funding formula leaves less-populated states with insufficient funds for even basic core infrastructure. Although DVP does not anticipate an increase in RPE funds, the new FOA includes a tiered funding structure that aims to make FOA activities more commensurate with each state's funding amount. Additionally, as a first step toward evaluating the innovative strategies being implemented by RPE grantees, the new FOA includes a focus on assessing state and local evaluation capacity. These assessments will provide a foundation for future evaluation capacity-building efforts in the RPE Program. DVP will be providing assessment tools, training, and technical assistance to support successful implementation of all FOA activities. Another recommendation from the panel, designed to strengthen the relationships of key RPE stakeholders in each state, was to require and document partnerships among state agencies, coalitions, and local programs. DVP has started to address this recommendation in the 1-year FOA by requiring all grantees to develop and sign a Memorandum of Understanding with their state sexual assault coalition that outlines the roles and responsibilities of each agency in implementing the RPE Program. DVP's work to build the evidence for preventive action and enhance grantees' capacity to evaluate the impact of their work is consistent with recent guidance from the Office of Management and Budget on the use of evidence and evaluation by government agencies (Memorandum from the Office on Management and Budget, May 18, 2012, available at www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/memoranda/2012/m-12-14.pdf).

Support high-quality surveillance and research activities

The panel recommended that DVP maintain or increase support for high-quality surveillance and research activities, emphasizing the continued use of rigorous methodologies to address research gaps and the need for ongoing funding of NISVS to highlight the scope and health consequences of SV. Current work in DVP is addressing several specific recommendations identified by the panel. For example, investment in NISVS is ongoing, with additional waves of data collection completed in 2011 and 2012. In an effort to disseminate findings from NISVS, several special reports are planned, including a report on victimization experiences by self-identified sexual orientation, experiences of victimization by female active duty military and wives of male active duty military, and three additional topical reports on IPV, SV, and stalking. To keep the surveillance work current, DVP is working to update the Sexual Violence Surveillance Definitions. DVP also led an effort, with support from partners in the SV/IPV fields, to add a new question to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey in 2013 that assesses SV in the context of teen dating relationships. This addition will strengthen the measurement of dating violence in the United States and provide separate prevalence estimates for physical violence and SV in the dating context.

The panel echoed DVP's concerns30,31 about the lack of effective, evidence-based prevention strategies for SV available to RPE grantees for implementation and encouraged continued investment in the development and evaluation of new approaches. DVP is currently funding rigorous evaluations of two universal, school-based interventions for youth (see discussions of Green Dot and Second Step).

In addition, the panel recommended that DVP continue to move beyond individual-level risk and protective factors to understand how factors at the outer levels of the social ecology influence risk for SV. DVP described the need to expand prevention efforts for SV to the outer levels of the social ecology in a recent article,31 and efforts are underway within DVP to identify policy-based strategies that have the potential to impact SV at the community level. DVP has also developed and is now evaluating Dating Matters™,32 a multilevel intervention for the prevention of teen dating violence (including SV) in high-risk urban communities. Dating Matters is based on the best available evidence of what works to reduce dating violence and includes preventive strategies for individuals, peers, families, schools, and neighborhoods. Further, DVP recently funded two studies (one focused on IPV and one focused on SV) to identify outer-level risk and protective factors for IPV/SV perpetration. This work will address critical gaps in the etiologic literature related to the development of new prevention approaches.

The panel identified a need for more information about ways that SV is similar to—and different from—other forms of violence, given evidence of high co-occurrence rates. Such knowledge can lead to the development of cross-cutting strategies that prevent multiple forms of violence. Toward this end, DVP is developing several publications, including a review of shared and unique risk factors for SV and youth violence that highlights evidence-based youth violence prevention strategies with potential for preventing SV.33

Enhance communication to improve the link between research and practice

In addition to the need for more research, the panelists highlighted a desire for more thorough and rapid dissemination of what is already known about SV, including research findings and success stories of grantees. The panel suggested that DVP more closely track grantee products and support efforts to disseminate these findings directly to the practice field. In addition, they recommended greater efforts to collect and share grantee success stories from the RPE program. In response to this recommendation, DVP is working with all RPE grantees to develop a success story that highlights a significant outcome or change as a result of the past 6 years of RPE funding. One example of DVP's current efforts to address the need for more direct dissemination of research to the practice field is the Applying Science, Advancing Practice (ASAP) initiative. ASAP is a series of brief research summaries created by DVP in an effort to apply scientific knowledge to the practice of primary prevention of violence. ASAP offers specialized, topic-specific information that is essential for successful and sustainable violence prevention efforts. A recent ASAP focused on links between bullying and SV and highlighted preliminary findings on the potential importance of homophobic teasing in the developmental pathway between bullying and SV perpetration. DVP is currently completing two large literature reviews of the SV etiologic and prevention evaluation literatures, with plans to translate these for RPE audiences as well.

The Future of SV Prevention at CDC

Moving forward, DVP will maintain its longstanding commitment to the prevention and eventual elimination of SV and its serious health consequences in the United States and worldwide. DVP's priorities for SV prevention will build on current and previous efforts, as well as the recommendations of the external panel. These priorities include continued investments in surveillance, research, and programmatic work on the primary prevention of SV perpetration.

Awareness and understanding of the magnitude and consequences of SV will be advanced through the institutionalization of the NISVS surveillance system. Continued investment in NISVS will provide information about the nature, scope, and consequences of SV at the state and national levels that the field can use to raise awareness about the importance of SV prevention, to estimate the social and fiscal impacts of SV on society, and to monitor trends over time. The ability to monitor trends in SV prevalence over time makes it possible to examine the impact of preventive interventions and policies at the community and societal levels. Further, NISVS will add to the knowledge base regarding the overlap between SV and other forms of violence, including IPV and stalking. DVP will update NISVS as needed to enhance the validity of the data and maintain the system's efficiency. DVP will continue to provide the field with summary reports of the data and special reports that focus on specific topics. NISVS is already informing media and public discourse about the role of SV and IPV in our society, as well as discussions by policymakers around the use of federal policy to prevent violence against women.

Advancing the evidence base for SV prevention is of the highest priority. DVP will continue its work to understand the etiology of SV perpetration, with increased attention to the identification of modifiable risk and protective factors at the community and societal levels. It is critical that DVP and the field work to expand the array of effective preventive strategies available for SV perpetration. For example, the RPE program has identified a number of promising prevention strategies that are in need of more rigorous evaluation. DVP will actively pursue opportunities to evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies and to assess the potential for dissemination. Furthermore, increased research investments will build the knowledge base around community-level change strategies for SV, with policy approaches being of particular interest. Going forward, it is essential that our research and programmatic efforts address multiple levels of the social ecology.

Finally, we must continue to increase the capacity for conducting prevention work by building on the successes of the RPE program and further supporting state and local health departments and community-based organizations in their ability to implement SV prevention efforts. The RPE program provides a robust infrastructure for implementing prevention strategies based on the best available research evidence throughout the United States. By continuing to increase grantee capacity to conduct practical program evaluation, DVP will support improved program accountability and implementation of SV prevention programs.

Communication with partners at the local level and data from such sources as NISVS continually remind CDC that SV is a far-reaching issue affecting the lives and health of millions of Americans. The magnitude of the problem and increased understanding of SV's long-term health consequences require that comprehensive evidence-based prevention strategies be widely disseminated and implemented at a level where the end of SV as a major public health problem is foreseeable. Guided by the accomplishments and knowledge gained in the last decade and progress toward current priorities, DVP's commitment to advancing the field of SV prevention is firm and will remain among the division's highest priorities.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of FHI 360 staff, the external contractor that gathered and synthesized information for the review, including Derek Inokuchi, M.H.S., Jesse Gelwicks, M.A., Kristina Hartman, M.H.S., Mika Yamashita, Ph.D., Willis Shawver, and Elyse Levine, Ph.D. We also thank the external peer review panel for their time, thoughtful feedback on the portfolio review, and recommendations to CDC.

Disclosure Statement

No conflicts of interest or competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Basile KC. Saltzman LE. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2002. Sexual violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black MC. Basile KC. Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report; Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman LA. Koss MP. Felipe Russo N. Violence against women: Physical and mental health effects. Part I: Research findings. Appl Prev Psychol. 1993;2:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basile KC. Smith SG. Sexual violence victimization of women: Prevalence, characteristics, and the role of public health and prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5:407–417. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercy JA. Hammond WR. Preventing homicide: A public heath perspective. In: Smith M, editor; Zahn M, editor. Studying and preventing homicide: Issues and challenges. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 274–294. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercy JA. Rosenberg ML. Powell KE. Broome CV. Roper WL. Public health policy for preventing violence. Health Affairs. 1993;12:7–29. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMahon PM. The public health approach to the prevention of sexual violence. Sexual Abuse. 2000;12:27–36. doi: 10.1177/107906320001200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basile KC. Implications of public health for policy on sexual violence. In: Prentky RA, editor; Janus ES, editor; Seto MC, editor. Sexually coercive behavior: Understanding and management. New York: New York Academy of Sciences; 2003. pp. 446–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saltzman LE. Green YT. Marks JS. Thacker SB. Violence against women as a public health issue: Comments from the CDC. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:325–329. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basile KC. Black MC. Simon TR. Arias I. Brener ND. Saltzman LE. The association between self-reported lifetime history of forced sexual intercourse and recent health-risk behaviors: Findings from the 2003 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tjaden P. Thoennes N. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 1998. Prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basile KC. Chen J. Black MC. Saltzman LE. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence victimization among U.S. adults, 2001–2003. Violence Vict. 2007;22:437–448. doi: 10.1891/088667007781553955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black M. Basile K. Breiding M. Ryan G. Prevalence of sexual violence against women in 23 states and two U.S. territories, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Violence Against Women In press. doi: 10.1177/1077801214528856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell R. Baker CK. Mazurek TL. Remaining radical? Organizational predictors of rape crisis centers' social change initiatives. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26:457–483. doi: 10.1023/a:1022115322289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ullman S. Review and critique of empirical studies of rape avoidance. Crim Justice Behav. 1997;24:177–204. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clay-Warner J. Avoiding rape: The effects of protective actions and situational factors on rape outcome. Violence Vict. 2002;17:691–705. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.6.691.33723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ullman SE. Rape avoidance: Self-protection strategies for women. In: Schewe PA, editor. Preventing violence in relationships: Interventions across the life span. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 137–162. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lonsway KA. Preventing aquaintance rape through education: What do we know. Psychol Women Q. 1996;20:229–265. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox PJ. Lang KS. Townsend SM. Campbell R. The Rape Prevention and Education (RPE) Theory Model of Community Change: Connecting individual and social change. J Fam Soc Work. 2010;13:297–312. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koss MP. Empirically enhanced reflections on 20 years of rape research. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20:100–107. doi: 10.1177/0886260504268601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller E. Tancredi DJ. McCauley HL, et al. “Coaching Boys into Men”: A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a dating violence prevention program. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercy JA. Having new eyes: Viewing child sexual abuse as a public health problem. Sexual Abuse. 1999;11:317–321. doi: 10.1177/107906329901100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basile KC. Sexual violence in the lives of girls and women. In: Kendall-Tackett KA, editor. The handbook of women, stress, and trauma. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2005. pp. 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noonan RK. Gibbs D. Empowerment evaluation with programs designed to prevent first-time male perpetration of sexual violence. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10:5S–10S. doi: 10.1177/1524839908329139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vivolo AM. Holland KM. Teten AL. Holt MK Sexual Violence Review Team. Developing sexual violence prevention strategies by bridging spheres of public health. J Womens Health. 2010;19:1811–1814. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coker A. Cook-Craig P. Williams C, et al. Evaluation of Green Dot: An active bystander intervention to reduce sexual violence on college campuses. Violence Against Women. 2011;17:777–796. doi: 10.1177/1077801211410264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basile KC. Espelage DL. Rivers I. McMahon PM. Simon TR. The theoretical and empirical links between bullying behavior and male sexual violence perpetration. Aggression Violent Behav. 2009;14:336–347. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Espelage D. Basile KC. Hamburger ME. Bullying perpetration and subsequent sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Applying science, advancing practice: The bully-sexual violence pathway in early adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tharp AT. DeGue S. Lang KR, et al. Commentary on Foubert, Godin, & Tatum (2010): The evolution of sexual violence prevention and the urgency for effectiveness. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26:3383–3392. doi: 10.1177/0886260510393010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeGue S. Holt MK. Massetti GM. Matjasko JL. Tharp AT. Valle LA. Looking ahead toward community-level strategies to prevent sexual violence. J Womens Health. 2012;21:1–3. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tharp A. Dating Matters: The next generation of teen dating violence prevention. Prev Sci. 2012;13:398–401. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeGue S. Massetti GM. Holt MK, et al. Identifying links between sexual violence and youth violence perpetration: New opportunities for sexual violence prevention. Psychol Violence. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0029084. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]