Abstract

Objective:

In developing countries, nutritional deficiency of essential trace elements is a common health problem, particularly among pregnant women because of increased requirements of various nutrients. Accordingly, this study was initiated to compare trace elements status in women with or without pre-eclampsia.

Materials and Methods:

In this study, serum trace elements including zinc (Zn), selenium (Se), copper (Cu), calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) were determined by using atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) in 60 patients and 60 healthy subjects.

Results:

There was no significant difference in the values of Cu between two groups (P > 0.05). A significant difference in Zn, Se, Ca and Mg levels were observed between patients with pre-eclampsia and control group (P < 0.001, P<0.01, P<0.01 and P<0.001, respectively). Zn, Se, Ca and Mg levels were found to be 76.49 ± 17.62 μg/ dl, 8.82 ± 2.10 μg/ dl, 8.65 ± 2.14 mg/dl and 1.51 ± 0.34 mg/dl in Pre-eclamptic cases, and these values were found statistically lower compared to the controls (100.61 ± 20.12 μg/dl, 10.47 ± 2.78 μg/dl, 9.77 ± 3.02 mg/dl and 1.78 ± 0.27 mg/dl, respectively). While Cu levels were 118.28 ± 16.92 and 116.55 ± 15.23 μg/dl in the patients and the healthy subjects, respectively. In addition, no significant difference was found between two groups with respect to Hemoglobin Concentration (HbC) and Total White Blood Cell Count (TWBC) (P>0.05).

Conclusion:

Our findings indicate that the levels of Zn, Se, Ca and Mg are significantly altered in pregnant women with pre-eclampsia. This research shows that these deficiencies can not due to hemodilution.

Keywords: Atomic absorption spectrometry, pre-eclampsia, trace elements

INTRODUCTION

Trace elements such as zinc (Zn), selenium (Se) and copper (Cu) display antioxidant activity, while others such as calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) are essential micronutrients. The disturbance in the metabolism of these elements may be a contributing factor in the development of certain diseases such as pre-eclampsia observed in pregnant women.

Minerals have important influence on the health of pregnant women and growing fetus. They are necessary during pregnancy and these elements should be supplemented as a daily requirement in pregnant women.[1]

Pre-eclampsia is a pregnancy-specific condition Characterized by high blood pressure, platelet aggregation and protein in urine.[2] Pregnancy-induced hypertension characterized by persistently elevated blood pressure of greater than 140/90 mm Hg.[3] It affects multiple organs including the liver, kidneys, brain and blood clotting system.

Pre-eclampsia contributes substantially to perinatal morbidity and mortality of both mother and newborn. The incidence of pre-eclampsia varies with the risk factor ranging from 2–8% of pregnancies.[4,5] In recent times, there has been an increasing prevalence in the incidence of pre-eclampsia globally, but there are conflicting reports on the relationship between trace elements and pre eclampsia. Despite several studies on pre-eclampsia, its aetiology has not yet been fully elucidated. Some studies have shown that changes in the levels of serum trace elements in pre-eclamptic patients may implicate its pathogenesis[6] while others have failed to show an association of serum levels of trace elements and prevalence of pre-eclampsia.[7]

It has reported an increased incidence of pre-eclampsia in zinc-deficient regions and it was later found that zinc supplementation reduced the high incidence of the disease.[8] Furthermore, decreased levels of zinc, selenium and copper have been observed in patients with pre-eclampsia.[9–11] Ugwuja and et al.[12] reported that only copper was found to be statistically significant. The obvious studies on serum calcium and magnesium levels in pregnant women showed that there is significant difference between two groups.[13–16] The present study was done to compare of serum trace elements level in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies in Iran. Atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) was used for the determination of these elements. In this study, the measurements were done directly after dilution. This method is very simple and suitable for the routine measurements compared to previous studies.

In this research to clear the role of trace elements in hemodilution, total White Blood Cell Count (TWBC) and Haemoglobin Concentration (HbC) were determined using standard laboratory techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study involved two groups of subjects. Group I (controls) was composed of 60 healthy subjects. Group II (pre-eclamptic women) was composed of 60 patients registered of women’s clinics of Tehran university and Sarem hospital (Tehran, Iran). The purposes of the study had been previously explained to all the participants and all were volunteers. A written informed consent was obtained from the participants in this study. Data for 60 pra-eclamptic and 60 control pregnant women matched for age, gestational age, anthropometrics and socioeconomic status were analyzed. Inclusion criteria were as physically healthy, single pregnancy, Gestational age of 30 to 40 weeks, willing to participate in the study, body mass index (BMI) between 19.11 to 30.21 Kg/m2 and at least 4 kg weight gain until third trimester of pregnancy.[17] The exclusion criteria included diagnosis of abnormal embryo in ultrasound, having chronic disease such as diabetes, chronic hypertension requiring antihypertensive therapy, chronic and severe disorders in kidneys, adrenal, liver, thyroid, parathyroid and cardiovascular disease, blood disorders, indigestion disorders, infections, malignant disorders, immune disorders, alcohol or drug addiction, smoking, severe stress during pregnancy, gynecological history, consumption of anti-cancer, anticoagulants, aspirins, more than 60 mg iron, calcium and medicines, which contain zinc.

Sample size determination for case-control studies are based on Cochran’s Formula (z = 1.96, Confidence Level = 95%). Zinc, selenium, copper, calcium and magnesium concentrations in serum of pre-eclamptic subjects were measured during this study and were compared to the control group.

Sample collection and treatment

This study (Research Project Number 102) was done from April to October 2011. The sampling of blood was performed in the Danesh laboratory (Tehran, Iran). Blood samples (10 ml) were taken at 8–9 a.m. after fasting and collected into polypropylene tubes containing lithium heparin (Vacuette, Geiner Labortechnik, Kremsmünter, Austria). Serum was separated within 2 h and aliquots were kept frozen at − 20°C until trace element analysis.[18] All laboratory wares including pipette tips and autosampler cups were cleaned thoroughly with detergent and tap water, rinsed with distilled water, soaked in dilute nitric acid and then rinsed thoroughly with deionized distilled water.

Laboratory procedures

The serum samples were diluted with chloric acid (0.1 N) for Zn, Cu, Ca and Mg measurements.[19] Determination of these elements performed on a flame atomic absorption (FAAS) spectrometer equipped with deuterium background correction (Spectr AA 220, Varian, Australia).

Se was determined by the graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (GFAAS) equipped with pyrolytically coated graphite tubes and deuterium background correction (SpectrAA 220, GTA 110, Varian, Australia). The samples were diluted 1:5 with 0.1% v/v Triton X-100. The solution of Mg(NO3)2 was used as matrix modifier in GFAAS, addition an appropriate furnace program.

The accuracy of the measurement was evaluated based on recovery studies and analysis of quality control material (QCM) (SeronormTM Trace Elements, serum, Level 1, Art. No. 201405, Norway).

Statistics

Statistical evaluation was carried out by using the SPSS 11.5 Version for Windows (USA, Houston). All results were expressed as mean values±SD. Group means comparisons were tested for significance by student’s t-test. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

RESULTS

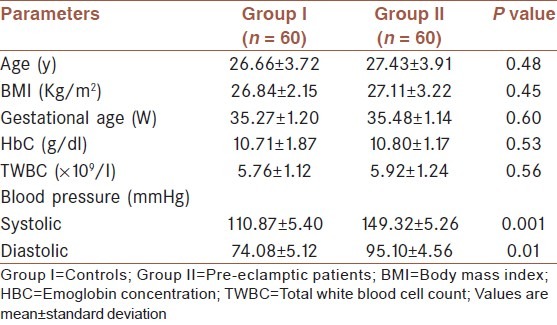

From Table 1, the normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies had comparable (P>0.05) body mass index (BMI) and gestational age. The mean ages of case and control groups were 27.43±3.91 years vs. 26.66±3.72 years (P>0.05). No significant difference was found between two groups with respect to Hemoglobin Concentration (HbC) and Total White Blood Cell Count (TWBC) (P>0.05). The results for blood pressure (BP) have been shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison between pre-eclampsia and control group

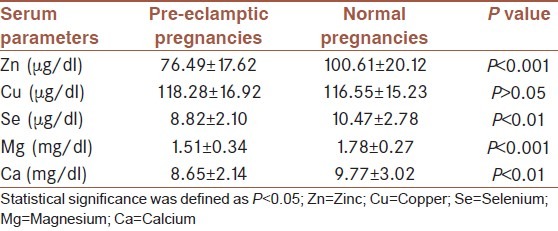

In Table 2, the values of Zn, Cu, Se, Mg and Ca in two groups are shown. On comparison between normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies, the serum Zn, Se, Mg and Ca levels significantly increased in normal pregnancy than pre-eclamptic (P<0.001, P<0.01, P<0.001 and P<0.01, respectively), but no statistically significant variations were observed in serum Cu concentration (P>0.05). This suggests a possible involvement of Zn, Se, Mg and Ca in the development and pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. However, the result must be interpreted with caution.

Table 2.

Biochemical data in pre-eclamptic subjects and control groups

DISCUSSION

The importance of the deficiencies of trace elements in pre-eclampsia relates to the fact that they are present in metalloprotein (Zn), ceruloplasmin (Cur), superoxide dismutases (Se and Zn) and glutathione peroxidase (Se). Unavailability of these elements due to deficiency or decrease concentration may be a predisposing factor in the development of pre-eclampsia or a contributing factor in its pathogenesis.

Metalloprotein (Zn) is an important trace element in metabolism, growth, development and reproduction. It is a constituent of many enzymes. This element plays important roles in nucleic acid metabolism and protein synthesis, as well as membrane structure and function. Zn deficiency has been associated with complications of pregnancy part of which is pre-eclampsia. Zn is passively transferred from mother to fetus across the placenta and there is also decreased Zn binding capacity of maternal blood during pregnancy, which facilitates efficient transfer of Zn from mother to fetus. During pregnancy, there is a decline in circulating Zn and this increases as the pregnancy progresses possibly due to decrease in Zn binding and increased transfer of Zn from the mother to the fetus.[20] Zn is essential for proper growth of fetus and the fall in Zn during pregnancy could also be a physiological response to expanded maternal blood volume.[21]

Recently, the role of oxidative stress or excessive lipid peroxidation has been implicated in pre-eclampsia. There is an imbalance between antioxidant enzyme activities and pro-oxidant production. Selenium, another important trace element, joins to many Se-dependent enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase. Decrease in the level of selenium is known to enhance pre-eclampsia by its resultant effect on glutathione peroxidase, an active enzyme in oxidative stress that reduces the formation of free radicals. So, the low concentration of selenium in serum exposes the subject to an accumulation of free radicals.

This study suggests that pre-eclampsia is associated with oxidative stress. This is in consonance with the view of Witzum[22] who reported that increased oxidative stress as a result of peroxidation of low density lipoproteins is a common phenomenon in pre-eclampsia. This complication is strictly regulated by antioxidants of which selenium forms a part.

Ca and Mg are very important for cellular metabolism such as muscle contractility, secretions, neuronal activity, as well as cellular death. In the present study, serum Ca and Mg levels in pre-eclamptic women were significantly lower than corresponding values in the control group, which is suggestive of some role of these elements in the rise of blood pressure. Although, Ca alone might play a role in the rise of blood pressure, a proper balance of Ca and Mg is of vital importance to control blood pressure because blood vessels need Ca to contract, but they also require sufficient Mg to relax and open up. Thus, Mg acts as a Ca channel blocker by opposing Ca dependent arterial constriction and by antagonizing the increase in intracellular Ca concentration leading to vasodilatation.[23–25]

Mg has established its role in obstetrics with its relationship to both fetal and maternal wellbeing. The low concentration of magnesium in serum exposes the subject to a risk of pregnancy complications, which includes pre-eclampsia. This is usually due to a defect in an enzymatic process which occurs as a result of low circulating Mg to function as a co-factor.

During pregnancy, there is a progressive decline in concentration of Ca and Mg in maternal serum possibly due to hemodilution, increased urinary excretion, and increased transfer of these minerals from the mother to the growing fetus.[9,11] In addition, low dietary intake and accelerated metabolism might be other contributing factors.

Determination of hematology parameters is of primary interest in connection with the detection of health problems in pregnant women. One of the hematological parameters that were used to define anaemia in mothers is HbC. In addition, TWBC is responsible for body defense. In this study, no significant difference was found between two groups with respect to HbC and TWBC (P>0.05). Our findings indicate Zn, Se, Ca and Mg deficiencies in pre-eclampsia can not due to hemodilution.

The results of this study revealed that the levels of serum trace elements which are the cofactor of antioxidant enzymes were affected in cases of pre-eclamptic pregnancy. The determination of the level of these parameters may be useful in the early determination of pre-eclampsia.

CONCLUSIONS

Serum Zn, Se, Mg and Ca levels were significantly fewer in the pre-eclamptic women in comparison with the normal subjects. This research indicates that these deficiencies in pre-eclampsia can not due to hemodilution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study is fifth sub-project of “Health-related Environmental Research” sponsored by Nuclear Science and Technology Research Institute (Tehran, Iran). The authors would like to thank Dr. Farnaz Sohrabvand (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences) for her consultation in completing this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rathore S, Gupta A, Batra HS, Rathore R. Comparative study of trace elements and serum ceruloplasmin level in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies with their cord blood. Biomed Res. 2011;22:207–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarsam DS, Shamden M, Al Wazan R. Expectant versus aggressive management in severe pre-eclampsia remote from term. Sing Med J. 2008;49:698–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (ACOG) Practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;99:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker JJ. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2000;356:1260–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02800-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2005;365:785–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17987-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James DK, Seely PJ, Weiner CP, Gonlk B. High risk pregnancy: management options. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Sauders; 2006. pp. 920–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caughey AB, Stotland NE, Washington AE, Escobar GJ. Maternal ethnicity, paternal ethnicity and parental ethnic discordance: Predictors of pre-eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:156–61. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000164478.91731.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam B, Malatyaliogu E, Alvur M, Talu C. Magnesium, zinc and iron levels in pre-eclampsia. J Matern Foetal Med. 2001;10:246–50. doi: 10.1080/714904340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rayman MP, Bode P, Redman CW. Low selenium status is associated with the occurrence of the pregnancy disease preeclampsia in women from the United kingdom. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;189:134–9. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00723-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akinloye O, Oyewale OJ, Oguntibeju OO. Evaluation of trace elements in pregnant women with pre-eclampsia. Afr J Biotech. 2010;9:5196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumru S, Aydin S, Simsek M, Sahin K, Yaman M. Comparison of Serum Copper, Zinc, Calcium, and Magnesium Levels in Pre-Eclamptic and Healthy Pregnant Women. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2003;94:105–12. doi: 10.1385/BTER:94:2:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ugwuja EI, Ejikeme BN, Ugwuja NC, Obeka NC, Akubugwo EI, Obidoa O. Comparison of Plasma Copper, Iron and Zinc Levels in Hypertensive and Non-hypertensive Pregnant Women in Abakaliki, South Eastern Nigeria. Pak J Nutr. 2010;9:1136–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukonpan K, Phupong V. Serum calcium and serum magnesium in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;273:12–6. doi: 10.1007/s00404-004-0672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bringman J, Gibbs C, Ahokas R. Differences in serum calcium and magnesium between gravidas with severe pre-eclampsia and normotensive controls. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:140–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aeli S, Khazaeli P, Ghasemi F, Mehdizadeh A. Serum magnesium and calcium ions in patients with severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia undergoing magnesium sulfate therapy. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idogun ES, Imarengiaye CO, Momoh SM. Extracellular Calcium and Magnesium in Preeclampsia and Eclampsia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2007;11:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowe SA, Brown MA, Dekker G, Gatt S, McLintock C, McMahon L, et al. Guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49:242–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arcasoy A, Canatan D, Sinav B, Kutlay L, Nurgul O, Muhtar S. Serum zinc levels and zinc binding capacity in thalassemia. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2001;15:85–7. doi: 10.1016/s0946-672x(01)80048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farzin L, Moassesi ME, Sajadi F, Amiri M, Shams H. Serum Levels of Antioxidants (Zn, Cu, Se) in Healthy Volunteers Living in Tehran. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2009;129:36–45. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamura T, Goldenberg RL, Johnston KE, DuBard M. Maternal plasma zinc concentrations and pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:109–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chitra U. Serum iron, copper and zinc status in mater-nal and cord blood. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2004;19:48–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02894257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witztum J. The oxidation hypothesis of atherosclerosis. Lancet. 2001;344:793–95. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Touyz RM. Role of magnesium in pathogenesis of hypertension. Mol Aspects Med. 2003;24:107–36. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(02)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Power ML, Heaney RP, Kalkwarf HJ, Pitkin RM, Repke JT, Tsang RC, et al. The role of calcium in health and disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1560–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70404-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skjaerven R, Wilcox A, Lie RT. The interval between pregnancies and the risk of pre-eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:33–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]