Abstract

Objectives. We examined news coverage of public debates about large taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) to illuminate how the news media frames the debate and to inform future efforts to promote obesity-related public policy.

Methods. We conducted a quantitative content analysis in which we assessed how frequently 30 arguments supporting or opposing SSB taxes appeared in national news media and in news outlets serving jurisdictions where SSB taxes were proposed between January 2009 and June 2011.

Results. News coverage included more discrete protax than antitax arguments on average. Supportive arguments about the health consequences and financial benefits of SSB taxes appeared most often. The most frequent opposing arguments focused on how SSB taxes would hurt the economy and how they constituted inappropriate governmental intrusion.

Conclusions. News outlets that covered the debate on SSB taxes in their jurisdictions framed the issue in largely favorable ways. However, because these proposals have not gained passage, it is critical for SSB tax advocates to reach audiences not yet persuaded about the merits of this obesity prevention policy.

A growing body of evidence indicates that consuming sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), which include nondiet sodas, energy drinks, and fruit drinks, is associated with higher obesity rates.1–3 Some researchers argue that SSBs are the single largest driver of increasing obesity rates in the United States.4 This evidence has led public health advocates and researchers to search for effective solutions to reduce SSB consumption.

Recent research suggests that large (e.g., penny per ounce) taxes on SSBs would reduce consumption and obesity rates.5,6 Although most US states already collect some form of tax on SSBs, these taxes are small relative to the price of these products.7 Many US states and cities (e.g., California, Mississippi, Philadelphia, PA) have considered larger taxes.8 To date, efforts to collect larger SSB taxes have been unsuccessful. Public opinion polls provide mixed evidence about public support for these taxes.9–11 One recent, national survey found substantially higher public agreement with anti-SSB tax than pro-SSB tax arguments.12

Understanding how the news media has framed SSB tax debates can shed light on how the political process has played out in various communities. Framing involves emphasizing some aspects of an issue to the exclusion of others.13 Advocates and opponents of specific policies seek to shape policy debates by framing the policy issue in ways that they see as favorable to their positions and by advocating media coverage that employs these frames.14–16 The news media, in turn, help to shape the policy agenda by selecting issues to cover and framing them in ways that invite particular policy interpretations.13,17,18 For example, an interest group might frame a policy issue by highlighting its economic consequences, whereas another group might make an explicit link between the issue and broader values, such as social justice. The news media choose to highlight these or other frames in their coverage, which in turn can influence how the public thinks about these issues.19 A systematic analysis of arguments used in support of and arguments used in opposition to a policy issue, as well as the types of advocates and opponents who participated in the debate, thus provides valuable political context about the issue in question.

Such contextual information is particularly important for policies on SSB taxes, characterized by politically polarized views among the public.10,20,21 SSB tax advocates are more likely to succeed at attracting large coalitions of support if they employ frames that resonate across the political spectrum.22 Identifying message frames that SSB tax proponents (typically leaning liberal) and opponents (typically leaning conservative) use and the news media cover can illuminate how various interest groups cast the terms of the debate to resonate with their constituents. Collecting data about the information environment can be helpful for designing future campaigns to increase support for SSB taxes and other obesity-related policies.23

METHODS

We conducted a quantitative content analysis to address 4 research questions: (1) How frequently are specific arguments supporting or opposing SSB taxes used in national news outlets and in outlets serving jurisdictions where SSB taxes have been proposed? (2) Does the use of pro- and anti-SSB tax arguments differ by characteristics of the news outlets (e.g., local vs national, opinion vs “hard” news)? (3) How often are specific types of pro- and anti-SSB tax sources cited in this coverage? (4) Does the use of pro- and anti-SSB sources differ by characteristics of the news outlets?

We used the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity Legislation Database to identify states and large cities that proposed new SSB taxes between January 1, 2009, and June 30, 2011 (20 jurisdictions; 17 states; and Baltimore, MD; Philadelphia, PA; and Washington, DC).24 We included only states that proposed large excise taxes (e.g., a penny or more per ounce tax), excluding states (e.g., Colorado, Utah) that considered small sales tax increases for soda and states (e.g., Washington) that considered small tax increases for both candy and soda, because research indicates that large excise taxes are required to reduce SSB consumption.5,6 Fifty-two different SSB tax proposals were offered in these jurisdictions during the study period; 49 were sponsored by a Democratic legislator, and 40 were offered in states with Democratic legislative majorities.

We selected up to 4 local newspapers serving the jurisdictions where these SSB tax proposals were considered, including (1) the largest circulation newspaper,25 selecting 2 if that jurisdiction was served by 2 major high-circulation newspapers (e.g., for California we included the Los Angeles Times and the San Francisco Chronicle); (2) the capital city newspaper (if not already represented through the first criterion); and where possible (3) another high-circulation newspaper with an opposing political orientation, which we measured using presidential endorsements in the 2008 election. We also included 5 national news sources, including the 2 highest circulation national newspapers (Wall Street Journal and USA Today)25 and transcripts of morning and evening news programs from 3 broadcast television networks (ABC, NBC, and CBS; Table 1).

TABLE 1—

News Sources Included in Sampling Frame: 2009–2011

| Outlet | City | SSB Tax Jurisdiction | 2008 Presidential Endorsement | No. of Articles |

| USA Today | McLean, VA | National | None | 6 |

| Wall Street Journal | New York, NY | National | None | 3 |

| ABC World News | New York, NY | National | None | 1 |

| ABC Good Morning America | New York, NY | National | None | 1 |

| CBS Evening News | New York, NY | National | None | 2 |

| CBS Early Show | New York, NY | National | None | 0 |

| NBC Nightly News | New York, NY | National | None | 1 |

| NBC Today Show | New York, NY | National | None | 1 |

| Arizona Republic | Phoenix, AZ | Arizona | Republican | 0 |

| Arizona Daily Star | Tucson, AZ | Arizona | Democrat | 1 |

| Sacramento Bee | Sacramento, CA | California | Democrat | 4 |

| Los Angeles Times | Los Angeles, CA | California | Democrat | 7 |

| San Diego Union-Tribune | San Diego, CA | California | Republican | 0 |

| Hartford Courant | Hartford, CT | Connecticut | Democrat | 0 |

| Connecticut Post | Bridgeport, CT | Connecticut | Republican | 0 |

| Washington Post | Washington, DC | Washington, DC | Democrat | 8 |

| Washington Times | Washington, DC | Washington, DC | Republican | 1 |

| Honolulu Star-Advertiser | Honolulu, HI | Hawaii | Democrat | 1 |

| State Journal-Register | Springfield, IL | Illinois | Democrat | 0 |

| Chicago Tribune | Chicago, IL | Illinois | Democrat | 5 |

| Chicago Sun-Times | Chicago, IL | Illinois | Democrat | 1 |

| The Topeka Capital-Journal | Topeka, KS | Kansas | None | 0 |

| The Wichita Eagle | Wichita, KS | Kansas | Unknown | 1 |

| The Baltimore Sun | Baltimore, MD | Baltimore, MD | Democrat | 0 |

| The Lansing State Journal | Lansing, MI | Michigan | Democrat | 1 |

| Detroit Free Press | Detroit, MI | Michigan | Democrat | 0 |

| Detroit News | Detroit, MI | Michigan | Republican | 0 |

| The Clarion-Ledger | Jackson, MS | Mississippi | Democrat | 3 |

| Concord Monitor | Concord, NH | New Hampshire | Democrat | 0 |

| New Hampshire Union Leader | Manchester, NH | New Hampshire | Republican | 0 |

| The Santa Fe New Mexican | Santa Fe, NM | New Mexico | Democrat | 0 |

| Albuquerque Journal | Albuquerque, NM | New Mexico | Republican | 0 |

| Times Union (Albany) | Albany, NY | New York | Democrat | 10 |

| New York Times | New York, NY | New York | Democrat | 14 |

| New York Post | New York, NY | New York | Republican | 3 |

| Salem Statesman-Journal | Salem, OR | Oregon | Democrat | 2 |

| Oregonian | Portland, OR | Oregon | Democrat | 0 |

| The Bulletin | Bend, OR | Oregon | Republican | 3 |

| The Philadelphia Inquirer | Philadelphia, PA | Philadelphia, PA | Democrat | 19 |

| The Providence Journal-Bulletin | Providence, RI | Rhode Island | Democrat | 5 |

| The Tennessean | Nashville, TN | Tennessee | Democrat | 2 |

| The Commercial Appeal | Memphis, TN | Tennessee | Democrat | 3 |

| Knoxville News Sentinel | Knoxville, TN | Tennessee | Republican | 0 |

| Austin American-Statesman | Austin, TX | Texas | Democrat | 0 |

| Houston Chronicle | Houston, TX | Texas | Democrat | 1 |

| Dallas Morning News | Dallas, TX | Texas | Republican | 0 |

| The Times Argus | Montpelier, VT | Vermont | Unknown | 3 |

| Burlington Free Press | Burlington, VT | Vermont | Democrat | 2 |

| Charleston Gazette | Charleston, WV | West Virginia | Democrat | 1 |

| Charleston Daily Mail | Charleston, WV | West Virginia | Republican | 0 |

Note. SSB = sugar-sweetened beverages.

News Coverage Selection

We used the LexisNexis, NewsBank, and ProQuest online archives to collect news stories focused on the SSB tax debate in the 50 news sources that met the selection criteria. For the 6 newspapers that were not indexed in these archives, we conducted searches in their online archives. Using the search term “tax,” we identified news stories that contained at least 1 of the words or phrases “soda,” “soft drink,” or “sugar-sweetened beverage” in the headline, lead paragraph, or abstract. This process produced an initial sample of 398 stories.

We excluded news articles from this sample if the major focus, which we defined as at least 50% of the news story, was not on SSB taxes. We also excluded corrections, letters to the editor, duplicate newswire stories, news story indexes for print news, and lead-ins for television news. This process yielded a final analytic sample of 116 news stories. We found the vast majority of these stories (n = 101) in local newspapers and the remainder (n = 15) in national news outlets.

Content Analysis

We developed a closed-ended, quantitative codebook to define discrete protax arguments, discrete antitax arguments, types of protax sources, and types of antitax sources cited in the news coverage. We began with a qualitative review of sampled articles to identify the breadth of discrete arguments employed in news stories about SSB taxes. This process led us to identify 30 discrete arguments, which we defined in a preliminary version of the quantitative codebook. The codebook then went through 3 rounds of pilot testing during which we adjusted the wording of items. We pretested the revised codebook using 24 news stories from news outlets not included in the sample frame. Two coders then analyzed articles for the presence or absence of arguments (with a 50% random subsample of news stories double coded), and 2 other coders analyzed the stories for the use of pro- and antitax sources (with all stories double coded).

We measured interrater reliability (assessed on the basis of the double-coded samples) for arguments and source types (all dichotomous variables) using κ, which adjusts for chance agreement. Raw agreement for these variables ranged from 87.9% to 100.0%, and κ ranged from κ = 0.65 to κ = 1.00; the average was κ = 0.87 (data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Reliability for the number of sources per article, measured using Krippendorff α (which calculates interrater reliability for interval variables), was 0.86.

Measures

We identified whether each of 15 pro-SSB tax and 15 anti-SSB tax arguments appeared in each news story (the wording of each item is available in a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We calculated the number of discrete pro- and anti-SSB tax arguments that appeared in each story. We also identified each person or organization that articulated a pro- or anti-SSB tax position in a news story, which we refer to as a source cited.

We coded each source as either pro- or anti-SSB tax. We also classified each source into 1 of 9 categories on the basis of the information provided in the article (data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We developed a hierarchy of categories to handle cases in which we identified a source as belonging to multiple groups (e.g., a member of the state legislature who is also a physician). When we had identified multiple categories, we assigned the source to the category listed first (e.g., politician but not physician).

Data Analysis

We compared the proportion of left-leaning versus right-leaning local newspapers (on the basis of their 2008 presidential endorsement) that covered the SSB tax debate during the study period, testing for differences using the χ2 test. In all subsequent analyses, we adjusted SEs for interdependence of observations by newspaper using SVY commands in Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

To address our first research question, we calculated the average number of discrete pro- and anti-SSB tax arguments appearing per story. We also calculated the proportion of stories offering each discrete pro- and anti-SSB tax argument and classes of pro- and anti-SSB tax arguments (e.g., health, economic, appropriate role of government) for the full sample. To address our second research question, we examined whether the number of discrete arguments and the presence or absence or particular arguments per story differed by characteristics of the news outlets, including local versus national and opinion (columns appearing in the editorial pages) versus hard news (stories appearing in traditional news sections), using ordinary least squares (OLS) or logistic regression, depending on the distribution of the dependent variable.

To address our third research question, we conducted a similar analysis of sources cited in news coverage of SSB tax debates. We calculated the average number of pro- and anti-SSB tax sources appearing per story. We also calculated the proportion of stories citing at least 1 pro-SSB tax source, at least 1 anti-SSB tax source, and at least 1 of both pro- and antitax sources. In addition, we calculated the proportion of stories that cited a pro- and anti-SSB tax source from each of 9 source categories (e.g., politicians, coalitions). To address our fourth research question, we tested whether the use of pro- and anti-SSB tax sources and source categories differed by news story characteristics using OLS and logistic regression.

RESULTS

Of the 101 local news stories covering taxes, 32 were opinion or op-ed, whereas 69 were hard news (there were no opinion pieces among the 15 national news stories). Left-leaning local newspapers were more likely to cover the SSB tax debate than were right-leaning newspapers (χ2 = 7.0; df = 1; P < .01). Among the 12 right-leaning newspapers in the sample, only 3 published at least 1 article on the issue (25%) for a total of 7 articles. Of the 27 left-leaning newspapers in the sample, 19 published at least 1 article (70%) for a total of 90 articles. There were no differences in the proportion of opinion pieces appearing in right-leaning (2 of 7 articles, 29%) or left-leaning (30 of 90 articles, 33%) newspapers.

Use of Pro- and Antitax Arguments

On average, news coverage included more discrete protax arguments (4.32 per story) than antitax arguments (2.01 per story; t = 5.87; P < .01). This difference was more pronounced in local news (4.30 protax vs 1.84 antitax arguments per story; t = 5.78; P < .001) than in national news (4.46 protax vs 3.13 antitax arguments per story; t = 2.54; P = .02) coverage.

Table 2 summarizes the proportion of stories offering discrete pro- and anti-SSB tax arguments, both overall and stratified by local or national outlets. A majority of stories included at least 1 protax argument (83%). Supportive arguments about the health consequences and financial benefits of SSB taxes appeared most often in news coverage (77% and 74% of stories, respectively). A smaller proportion of stories offered favorable comparisons between SSB taxes and tobacco taxes (30%), discussed undue influence from the food and beverage industry in the political process (32%), or mentioned the benefits of SSB taxes for children or the poor (28%). There were few differences between local and national news outlets in the use of protax arguments.

TABLE 2—

Proportion of News Stories Including Discrete Pro– and Anti–Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax Arguments: 2009–2011

| Argument | Local (n = 101), Proportiona (95% CI) | National (n = 15), Proportiona (95% CI) | Overall (n = 116), Proportiona (95% CI) |

| Any pro-SSB tax argument | 0.82 (0.73, 0.91) | 0.87 (0.68, 1.00) | 0.83 (0.75, 0.91) |

| Any pro-SSB tax financial argument | 0.73 (0.65, 0.81) | 0.80 (0.61, 0.99) | 0.74 (0.67, 0.81) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax because the relative price of SSBs is lower than is healthier food and beverage options | 0.08 (0.03, 0.13) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.07 (0.02, 0.11) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax as an appropriate approach to raising revenue, saving money, or balancing budgets | 0.73 (0.65, 0.81) | 0.80 (0.61, 0.99) | 0.74 (0.67, 0.81) |

| If yes, argues SSB tax revenue to be used specifically for obesity prevention or treatment | 0.34 (0.23, 0.45) | 0.20 (0.01, 0.39) | 0.32 (0.22, 0.42) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax to reduce health care spending | 0.14 (0.04, 0.24) | 0.20 (0.00, 0.41) | 0.15 (0.05, 0.24) |

| If yes, mentions reduced health care spending specifically on obesity | 0.07 (0.00, 0.16) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.06 (0.00, 0.14) |

| Any pro-SSB tax health argument | 0.75 (0.62, 0.89) | 0.87 (0.69, 1.00) | 0.77 (0.65, 0.89) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax because SSB consumption is a cause of obesity | 0.46 (0.33, 0.58) | 0.53 (0.37, 0.69) | 0.47 (0.36, 0.57) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax because SSB consumption is a cause of other health conditions | 0.23 (0.13, 0.32) | 0.33 (0.13, 0.54) | 0.24 (0.15, 0.33) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax because it could decrease the prevalence of obesity | 0.50 (0.38, 0.61) | 0.60 (0.38, 0.82) | 0.51 (0.40, 0.62) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax because it could decrease morbidity or mortality or increase health | 0.30 (0.21, 0.39) | 0.40 (0.22, 0.58) | 0.31 (0.23, 0.40) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax because it could reduce SSB consumption | 0.50* (0.35, 0.64) | 0.73* (0.62, 0.85) | 0.53 (0.40, 0.65) |

| Any pro-SSB tax vulnerable populations argument | 0.31 (0.19, 0.43) | 0.13 (0.00, 0.28) | 0.28 (0.18, 0.39) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax because it could help children and adolescents | 0.23 (0.12, 0.33) | 0.07 (0.00, 0.21) | 0.21 (0.11, 0.30) |

| Argues in favor of SSB tax because it could help the poor | 0.08 (0.03, 0.13) | 0.07 (0.00, 0.16) | 0.08 (0.03, 0.13) |

| Pro-SSB tax political feasibility argument, argues in favor of SSB tax by noting increasing or high public support for SSB tax | 0.03 (0.00, 0.06) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.05) |

| Pro-SSB tax analogy argument, argues in favor of SSB tax using analogy to tobacco tax | 0.29 (0.18, 0.39) | 0.40 (0.20, 0.60) | 0.30 (0.21, 0.40) |

| Pro-SSB tax role of government argument, argues in favor of SSB tax by noting that food and beverage industry unduly influences the political process | 0.35 (0.25, 0.45) | 0.13 (0.00, 0.32) | 0.32 (0.21, 0.42) |

| Any anti-SSB tax argument | 0.65** (0.55, 0.73) | 0.93** (0.84, 1.00) | 0.68 (0.59, 0.77) |

| Any anti-SSB tax financial argument | 0.47 (0.34, 0.61) | 0.47 (0.31, 0.63) | 0.47 (0.35, 0.60) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax because it could hurt the economy | 0.31 (0.20, 0.41) | 0.33 (0.10, 0.57) | 0.31 (0.22, 0.40) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax because it represents an inappropriate approach to raising revenue or balancing budgets | 0.28 (0.19, 0.37) | 0.27 (0.11, 0.42) | 0.28 (0.20, 0.36) |

| Any anti-SSB tax health argument | 0.31 (0.23, 0.38) | 0.47 (0.22, 0.71) | 0.33 (0.25, 0.40) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax because evidence is unclear whether SSB consumption is a cause of obesity | 0.09 (0.02, 0.16) | 0.13 (0.00, 0.28) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.16) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax because evidence is unclear whether SSB consumption is a cause of other health conditions | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax because evidence is unclear whether it could decrease the prevalence of obesity | 0.20 (0.14, 0.25) | 0.33 (0.13, 0.54) | 0.22 (0.16, 0.27) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax because evidence is unclear whether it could decrease morbidity or mortality or increase health | 0.09 (0.02, 0.16) | 0.07 (0.00, 0.16) | 0.09 (0.02, 0.15) |

| Anti-SSB tax vulnerable populations argument, argues in opposition to SSB tax because SSB taxes hurt the poor | 0.14** (0.09, 0.19) | 0.53** (0.34, 0.72) | 0.19 (0.11, 0.27) |

| Any anti-SSB tax political feasibility argument | 0.07 (0.01, 0.13) | 0.20 (0.01, 0.39) | 0.09 (0.02, 0.15) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax by noting that few jurisdictions have enacted SSB taxes or that proposals have failed to pass | 0.05 (0.00, 0.10) | 0.07 (0.00, 0.16) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.10) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax by noting low public support for SSB tax | 0.02* (0.00, 0.05) | 0.13* (0.00, 0.28) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.07) |

| Any anti-SSB tax analogy | 0.11 (0.01, 0.21) | 0.27 (0.11, 0.42) | 0.13 (0.04, 0.22) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax using analogy to tobacco tax | 0.11 (0.01, 0.21) | 0.20 (0.05, 0.35) | 0.12 (0.03, 0.21) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax using analogy to alcohol tax | 0.01* (0.00, 0.03) | 0.13* (0.00, 0.32) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.07) |

| Any anti-SSB tax role of government argument | 0.39b (0.28, 0.49) | 0.67b (0.41, 0.93) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.53) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax because the beverage industry is already making voluntary changes that are sufficient | 0.06b (0.02, 0.10) | 0.27b (0.00, 0.59) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.14) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax as an inappropriate intrusion of government | 0.17 (0.08, 0.26) | 0.20 (0.05, 0.35) | 0.17 (0.09, 0.26) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax because it does not target other unhealthy foods | 0.27 (0.19, 0.34) | 0.27 (0.04, 0.49) | 0.27 (0.19, 0.34) |

| Argues in opposition to SSB tax as a slippery slope to more government taxation | 0.06b (0.01, 0.11) | 0.20b (0.01, 0.39) | 0.08 (0.02, 0.13) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage. P values denote significant difference between local and national coverage derived from logistic regression models using survey weights.

After adjusting SEs to account for lack of independence in observations by news source.

Denotes differences between local and national sources that approached significance at P < .1.

*P < .05; **P < .01.

Although a majority of stories included at least 1 antitax argument (68%), overall coverage was less likely to include an antitax argument than a protax argument (F(1, 30) = 5.43; P = .03). However, national news outlets offered more coverage with competing frames than did local news. National outlets were more likely than were local outlets to include at least 1 antitax argument (93% vs 65%; P < .01). In local newspapers, hard news stories were more likely than were opinion stories to offer an antitax argument (76% vs 44%; P < .05). After excluding opinion stories, national outlets were still more likely to include at least 1 antitax argument than were local outlets (93% vs 76%; P < .05). In addition, 80% of national stories offered both pro- and antitax arguments; less than half of local stories did so (48%; P = .09; data not shown). This difference occurred because every opinion story appearing in a local newspaper offered arguments on only 1 side of the SSB tax debate, a majority of which were protax (56%).

The most frequent opposing arguments focused on how SSB taxes would hurt the economy and constituted inappropriate governmental intrusion (47% and 42% of stories, respectively). One third (33%) of articles offered a position that suggested evidence was unclear or lacking about the health benefits of an SSB tax. A smaller proportion of stories cited the argument that an SSB tax would be regressive (19%), offered negative analogies between SSB taxes and tobacco or alcohol taxes (13%), or described the tax as politically infeasible (9%). National stories were more likely than were local stories to offer arguments about how the tax could hurt the poor (53% vs 14%), had low public support (13% vs 2%), was not analogous to alcohol taxes (13% vs 1%), or constituted an inappropriate role for government (67% vs 39%).

Use of Pro- and Antitax Sources

In each news story, a comparable number of pro- and anti-SSB tax news sources were cited overall (2.34 and 2.04, respectively); this did not differ between national and local outlets. Most stories cited at least 1 protax source (89%). Significantly fewer stories (although still a majority at 73%) cited at least 1 antitax source (F(1,30) = 9.72; P < .01). This pattern also did not differ between national and local outlets.

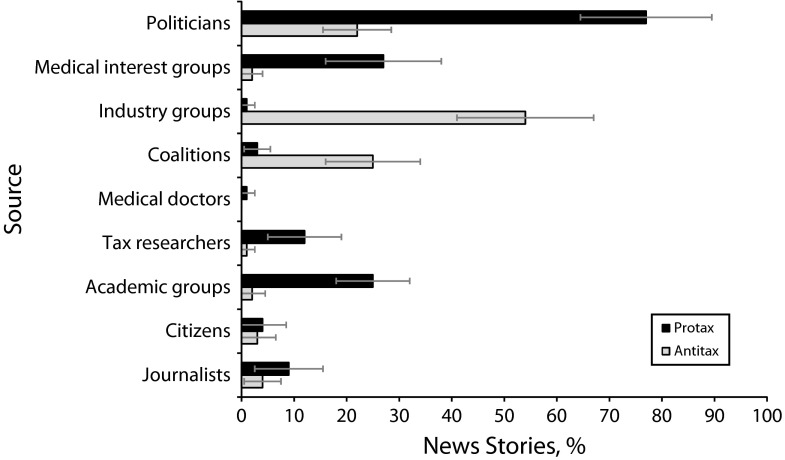

Figure 1 shows the proportion of stories citing pro- and antitax sources from 9 categories. The most common protax source categories were politicians (77%), medical interest groups (27%), and academic organizations (25%). The most common antitax source categories were industry groups (54%), coalitions (25%), and politicians (22%). Figure 1 also reveals differences in the distribution of arguments across sources. Whereas several types of sources (politicians, medical interest groups, physicians, researchers, and academic groups) frequently made protax arguments, antitax arguments were mostly confined to 2 source groups, industry groups and proindustry coalitions. A substantial number of stories also cited antitax politicians, but these citations occurred at a much lower rate than did those of protax politicians. Two source categories differed between local and national outlets (data not shown). Local outlets were more likely than were national ones to cite protax politicians (81% vs 47%; P = .03), and national outlets were more likely than were local outlets to cite protax researchers (33% vs 9%; P < .01).

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of news stories using pro– and anti–sugar-sweetened tax sources: 2009–2011.

Note. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Public debates about policy solutions to health problems occur in a dynamic and competitive political context. Democratic legislators in jurisdictions that Democratic legislative majorities control sponsored the majority of SSB taxes. Not surprisingly, there were more left-leaning newspapers in these jurisdictions, and left-leaning local newspapers were much more likely than were right-leaning newspapers to publish news stories focused on the SSB tax debate. Left-leaning newspapers thus appear to view SSB taxes as a more newsworthy issue than do right-leaning newspapers. This coverage is likely to shape which issues are perceived as important and worthy of policy deliberation.24,26,27 Because of these coverage differences, readers of left-leaning newspapers may be more aware of arguments in favor of SSB taxes than are readers of right-leaning newspapers. Republican opposition to SSB taxes, well-documented in public opinion polls, could also be a result of more ideologically based opposition to a tax in the absence of significant coverage of the issue.9,10

Relative Proportion and Nature of Arguments and Sources

News stories focused on the SSB tax debate were more likely to offer pro- than antitax arguments. Although the vast majority of local news stories originating from left-leaning newspapers in part shaped this finding, even the national news outlets in the sample that have no public record of political orientation (because they do not formally endorse political candidates) offered more protax than antitax arguments. The relative intensity of pro- to antitax arguments in news coverage alone suggests that protax advocates enjoyed success at generating favorable news coverage of the issue. However, it is also critical to consider the perceived strength and resonance of arguments leveraged on both sides of this issue, because the types of arguments offered in support of the tax differed from the types of arguments offered in opposition.

The most common pro-SSB tax arguments focused on health and economic benefits and paid particular attention to the tax’s potential to raise governmental revenue, reduce SSB consumption, and lower obesity rates. The most common types of anti-SSB tax arguments offered were economic or ideological, although economic arguments against the tax were substantively different from economic arguments for it. Specifically, the most frequently used antitax arguments concerned potentially negative effects of the tax on the economy at large (rather than revenue for the government), taxes as an inappropriate way to raise revenue or reduce budget deficits, and the idea that the tax is arbitrary because it focuses exclusively on 1 class of products (SSBs) rather than other unhealthy items (e.g., snack foods, chips, candy).

Although some news stories offered antitax arguments that questioned the evidence supporting the connection between SSB consumption, SSB taxes, and health outcomes, this class of argument appeared in only one third of all tax-related stories. Future work should explore which types of arguments resonate among the public and policymakers who are considering these policies.

Differences in Arguments and Sources by News Source

Local and national news outlets differed substantially in their inclusion of arguments against SSB taxes. A notable proportion of local news stories were editorial page stories in which one might expect authors to make 1-sided arguments. However, even in hard news stories, local stories were less likely than national stories to offer an antitax argument. National news stories were also less likely to cite politicians and more likely to cite researchers in their coverage. These differences may stem from the fact that our local news sample was composed overwhelmingly of left-leaning newspapers. Research suggests coverage differences may also result from structural differences between national and local news in time and money allocated to research, ease of access to local politicians with specific policy agendas, and reliance on press releases or public relations efforts from advocacy groups.28

Opinion stories offered exclusively 1-sided arguments, a majority of which were in favor of an SSB tax. News coverage with only pro-SSB tax messages might appear at first blush to be conducive to the passage of SSB tax bills; however, prominent work in political science suggests that this might not be the case.29 Recent studies have aimed to capture the real world of political debates more faithfully by exposing people to competing frames about policy issues over multiple time points. These studies suggest that framing effects on public support for a particular policy can be enhanced not by exposing people only to 1-sided arguments about the policy issue but by presenting arguments about both sides of the issue that vary in their strength and timing.29 More research, ideally conducted in an experimental or longitudinal context, is necessary to ascertain how the valence and timing of pro- and anti-SSB tax arguments influence public views on this policy issue.

Limitations

We analyzed the content of local and national newspaper coverage and transcripts from national news broadcasts on SSB taxes. Yet, information about SSB taxes is increasingly available through alternative news sources not included in this study such as blogs, news aggregator sites, and newspaper Web sites.

Our sample frame did not include local television news or special interest publications (e.g., media targeting specific racial or ethnic groups). Although most readers of online news also read print sources,30 we did not capture the full breadth and depth of the SSB tax debate available to the public. Furthermore, our results do not offer direct evidence about whether exposure to arguments in these news outlets influenced opinions among their readers.

Conclusions

We have provided data on the nature of pro- and anti-SSB tax arguments and sources that have been used to characterize the debate in the news media. Despite favorable framing among the news outlets that chose to cover the policy debate on SSB taxes, these proposals have not gained passage. Future research should monitor the evolution of SSB tax–related discourse in the news media, academic research, public opinion, and legislative debate over time. These efforts could further enhance our understanding of the role these outlets play in shaping obesity-related policy.

Acknowledgments

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Healthy Eating Research Program (grants 69173 and 68051) funded this study.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the expert research assistance of Judy Jou, Jaimee Kerber, and Sooyeon Kim.

Human Participant Protection

This research did not involve human participants and thus is not subject to institutional review board approval.

References

- 1.Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet. 2001;357(9255):505–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):667–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forshee RA, Anderson PA, Storey ML. Sugar-sweetened beverages and body mass index in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1662–1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownell KD, Friedan TR. Ounces of prevention—the public policy case for taxes on sugared beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(18):1805–1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sturm R, Powell LM, Chriqui JF, Chaloupka FJ. Soda taxes, soft drink consumption, and children’s body mass index. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):1052–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkelstein EA, Zhen C, Nonnemaker J, Todd JE. Impact of targeted beverage taxes on higher- and lower-income households. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2028–2034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chriqui JF, Eidson SS, Bates Het al. State sales tax rates for soft drinks and snacks sold through grocery stores and vending machines. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29(2):226–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugar-sweetened beverage tax legislation. Yale University Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity. Available at: http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/resources/upload/docs/what/policy/SSBtaxes/SSBTaxMap_2011.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2012.

- 9.Field Research Corporation; California Center for Public Health Advocacy. Soda Tax Polls; 2010. Available at http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/resources/upload/docs/what/policy/SSBtaxes/CCPHAPollSodaTax3.10.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2012.

- 10.Quinnipiac University Polling Institute. Quinnipiac University Poll; 2008. Available at: http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/resources/upload/docs/what/policy/SSBtaxes/QuinnipiacPollFatTaxes12.08.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2012.

- 11.Over half of Americans opposed to taxing soft drinks and fast food. Harris Interactive. Available at: http://www.harrisinteractive.com/NewsRoom/HarrisPolls/tabid/447/mid/1508/articleId/402/ctl/ReadCustom%20Default/Default.aspx. Accessed February 8, 2012.

- 12.Barry CL, Niederdeppe J, Gollust SE. Framing the debate over sugar-sweetened beverage taxes. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):158–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Entman RM. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun. 1993;43(4):51–58 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumgartner FR, Jones BD. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilgartner H, Bosk C. The rise and fall of social problems: a public arenas model. Am J Sociol. 1998;94(1):53–78 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyengar S. Is Anyone Responsible? Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson TE, Clawson RA, Oxley ZM. Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1997;91(3):567–583 [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCombs ME, Shaw DL. The evolution of agenda-setting research: twenty-five years in the marketplace of ideas. J Commun. 1993;43(2):58–67 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheufele DA. Agenda-setting, priming, and framing revisited: another look at cognitive effects of political communication. Mass Commun Soc. 2000;3(2–3):297–316 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barry CL, Brescoll VL, Brownell KD, Schlesinger M. Obesity metaphors: how beliefs about the causes of obesity affect support for public policy. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):7–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederdeppe J, Porticella N, Shapiro M. Using theory to identify beliefs associated with support for policies to increase the price of high-fat and high-sugar foods. J Health Commun. 2012;17(1):90–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snow DA, Benford RD. Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. Int Soc Mov Res. 1988;1(1):197–217 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin EW, Pinkleton BE. Strategic Public Relations Management: Planning and Managing Effective Communication Programs. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity. Legislation database. Available at: http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/legislation. Accessed February 8, 2012.

- 25.New Audit Bureau of Circulations. Newspaper search. http://abcas3.accessabc.com/ecirc/newsform.asp. Accessed February 24, 2012.

- 26.McCombs ME, Shaw DL. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin Q. 1972;36(2):176–187 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iyengar S, Kinder DR. News That Matters: Television and American Opinion. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donsbach W. Psychology of news decisions: factors behind journalists’ professional behavior. Journalism. 2004;5(2):131–157 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chong D, Druckman JN. Dynamic public opinion: communication effects over time. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2010;104(4):663–680 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chyi HI, Lewis SC. Use of online newspaper sites lags behind print editions. Newspaper Res J. 2009;30(4):38–53 [Google Scholar]